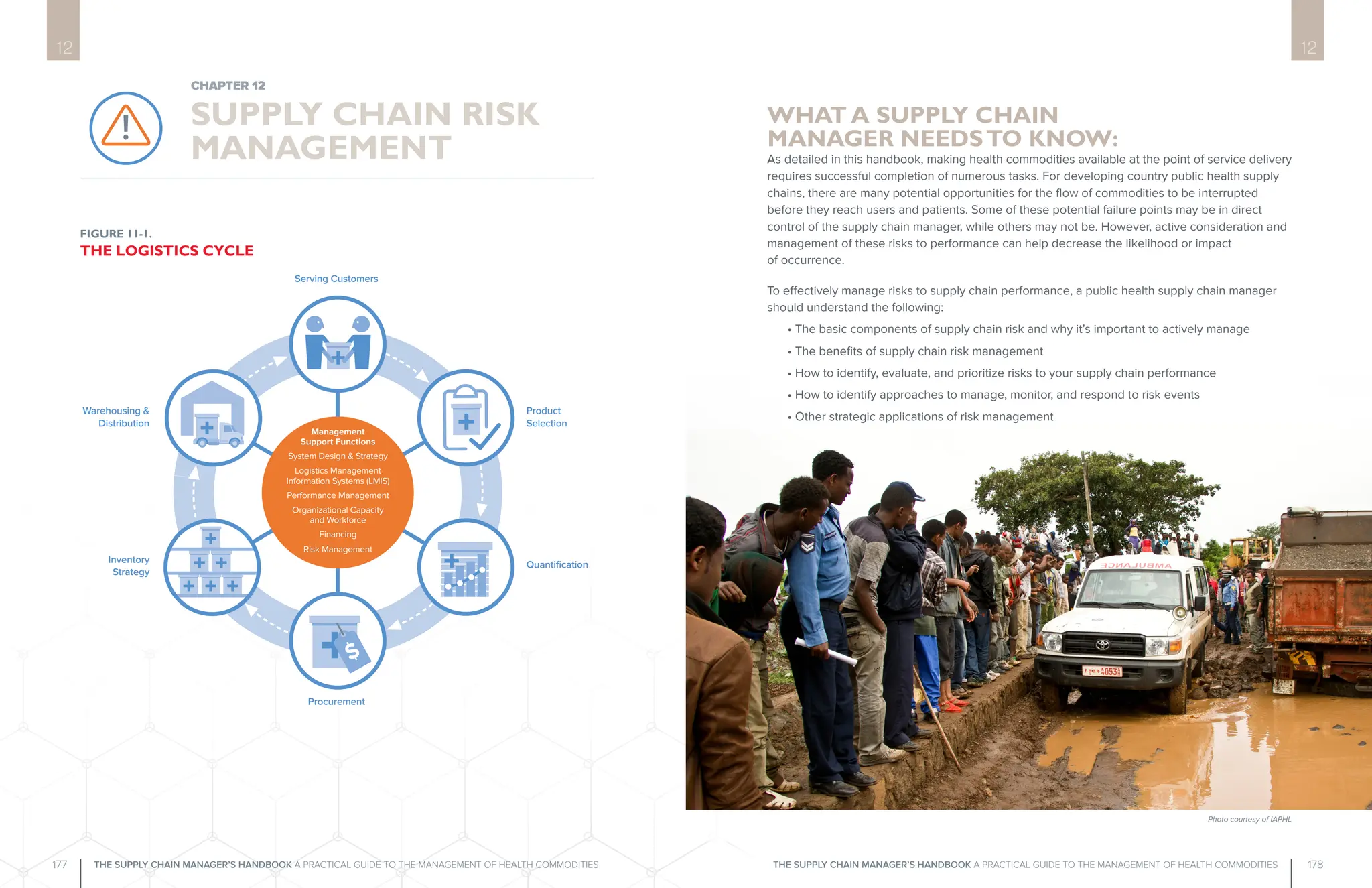

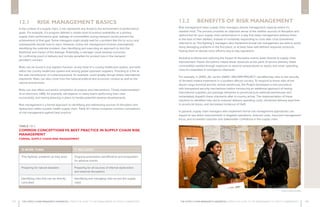

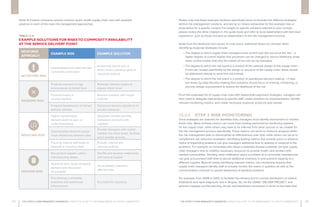

The Supply Chain Manager's Handbook provides a comprehensive guide on effectively managing health commodities within public health logistics, focusing on risk management strategies. It outlines the importance of identifying, evaluating, prioritizing, and responding to risks that can disrupt supply chain performance, with methodologies for implementation including risk assessment, planning, monitoring, and incident handling. Additionally, the document emphasizes the benefits of proactive risk management, such as reducing stockouts and operational costs, thereby improving overall supply chain efficiency.