Embed presentation

Downloaded 13 times

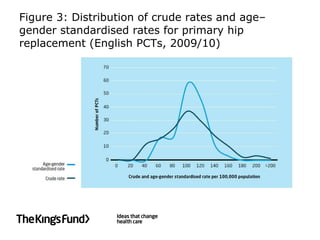

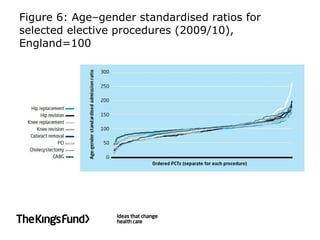

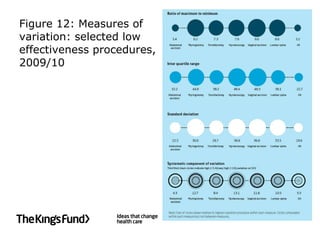

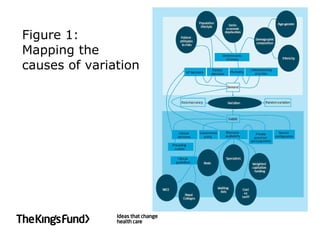

The document discusses variations in health care, emphasizing the importance of maximizing positive variations while minimizing negative ones. It highlights the challenges in distinguishing between harmful and beneficial variations, as well as the implications of overuse and underuse of medical services. This report aims to provide insights into how professional knowledge and its application can influence patient-centered care.