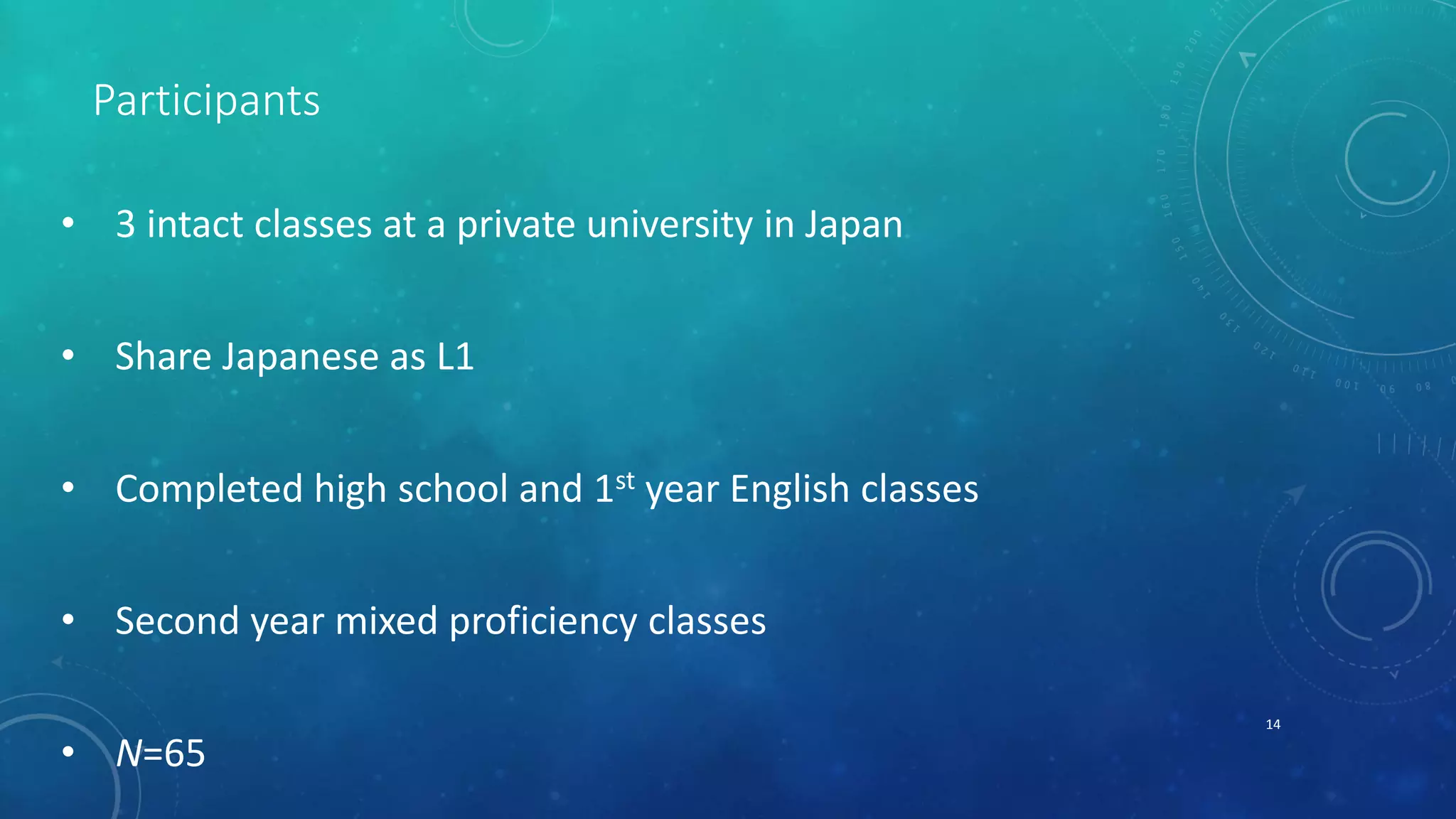

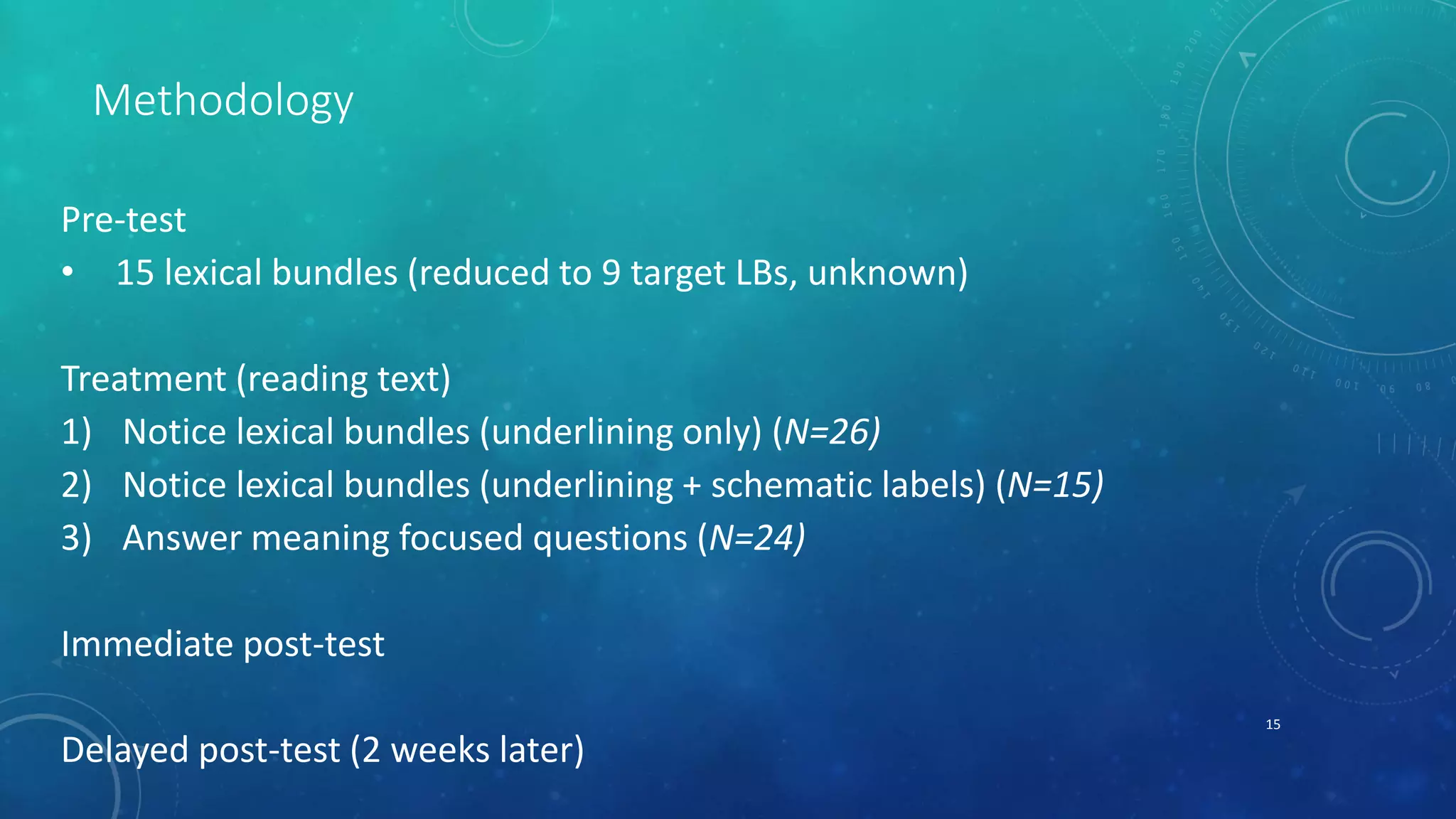

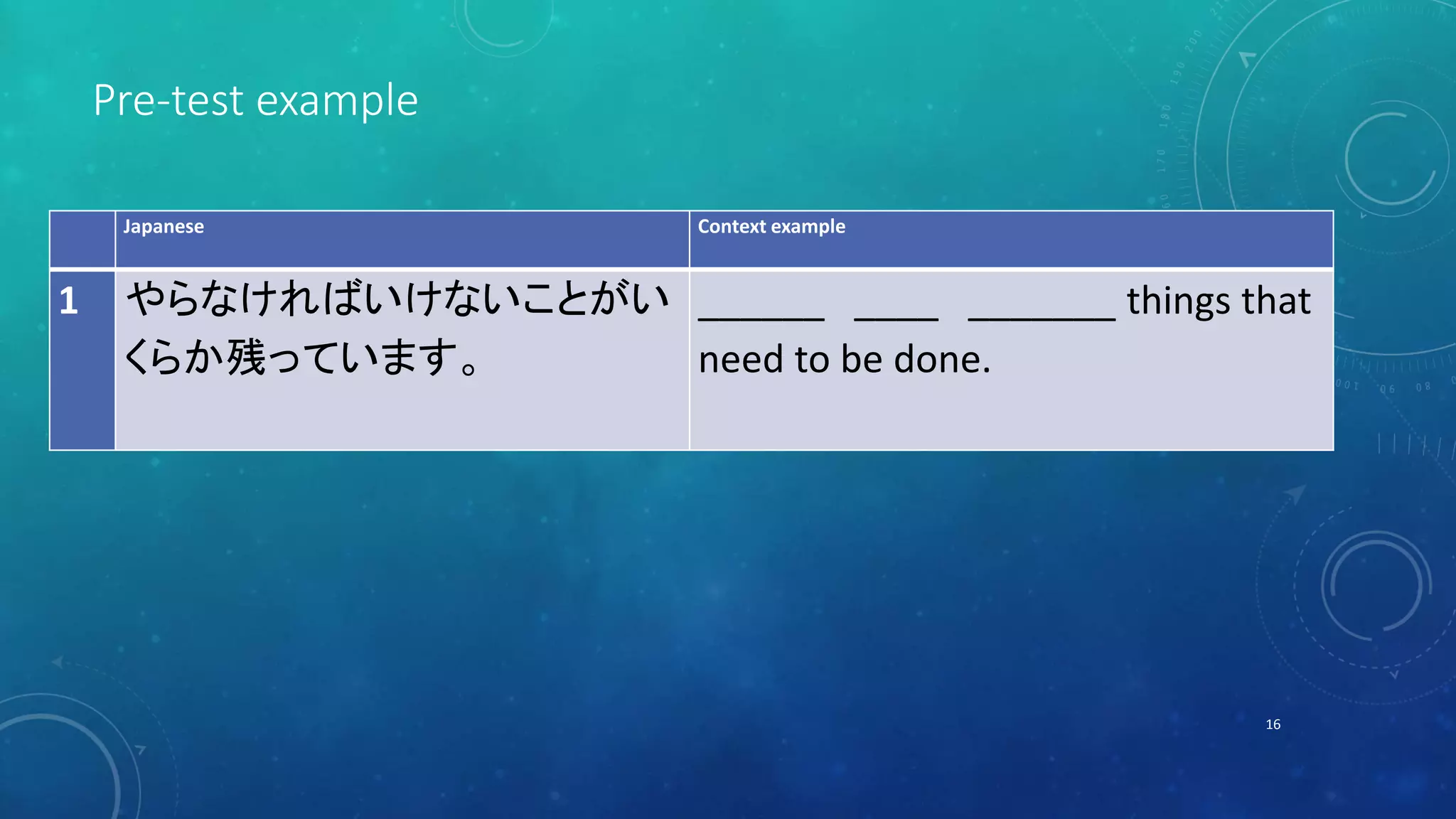

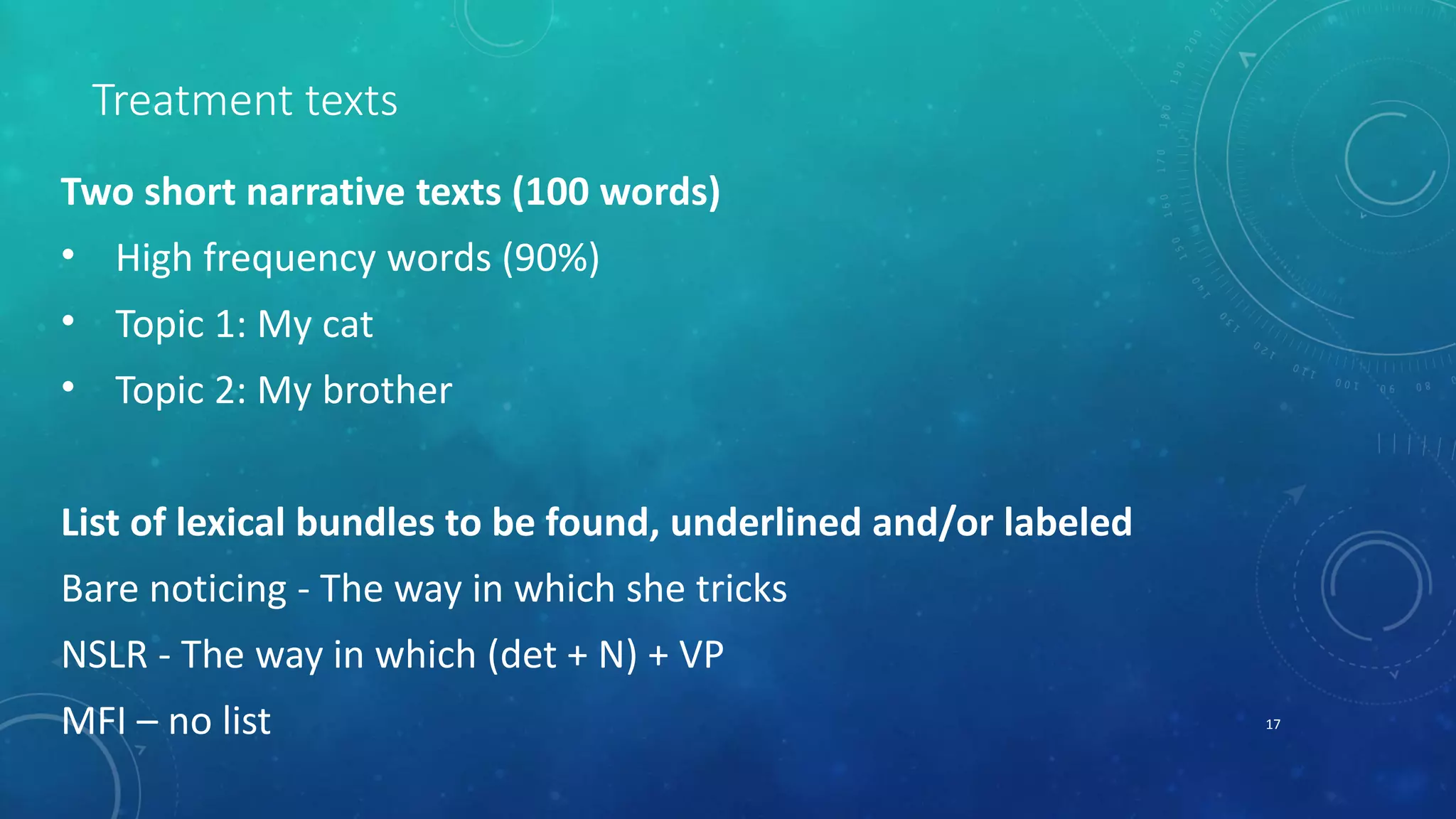

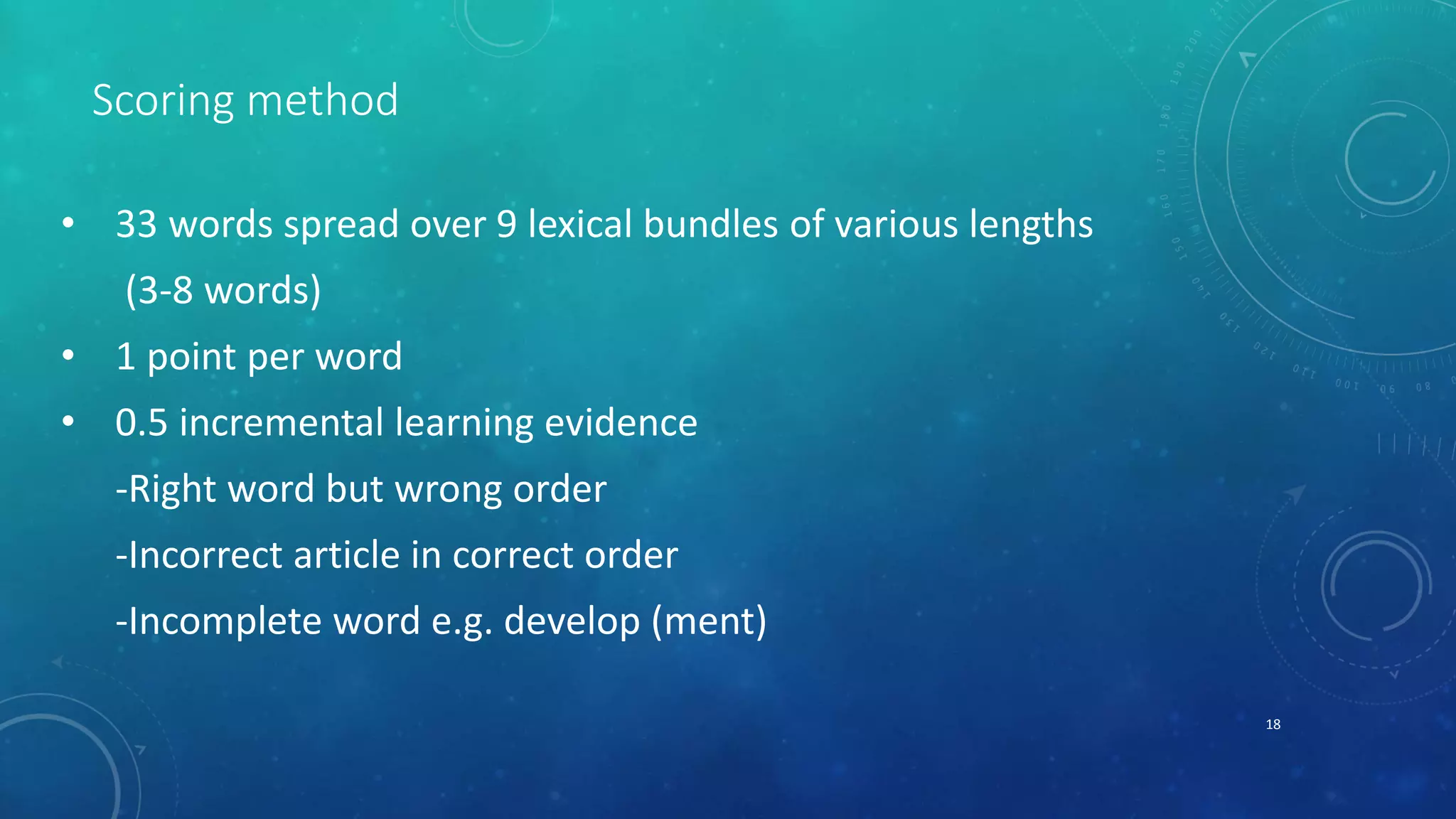

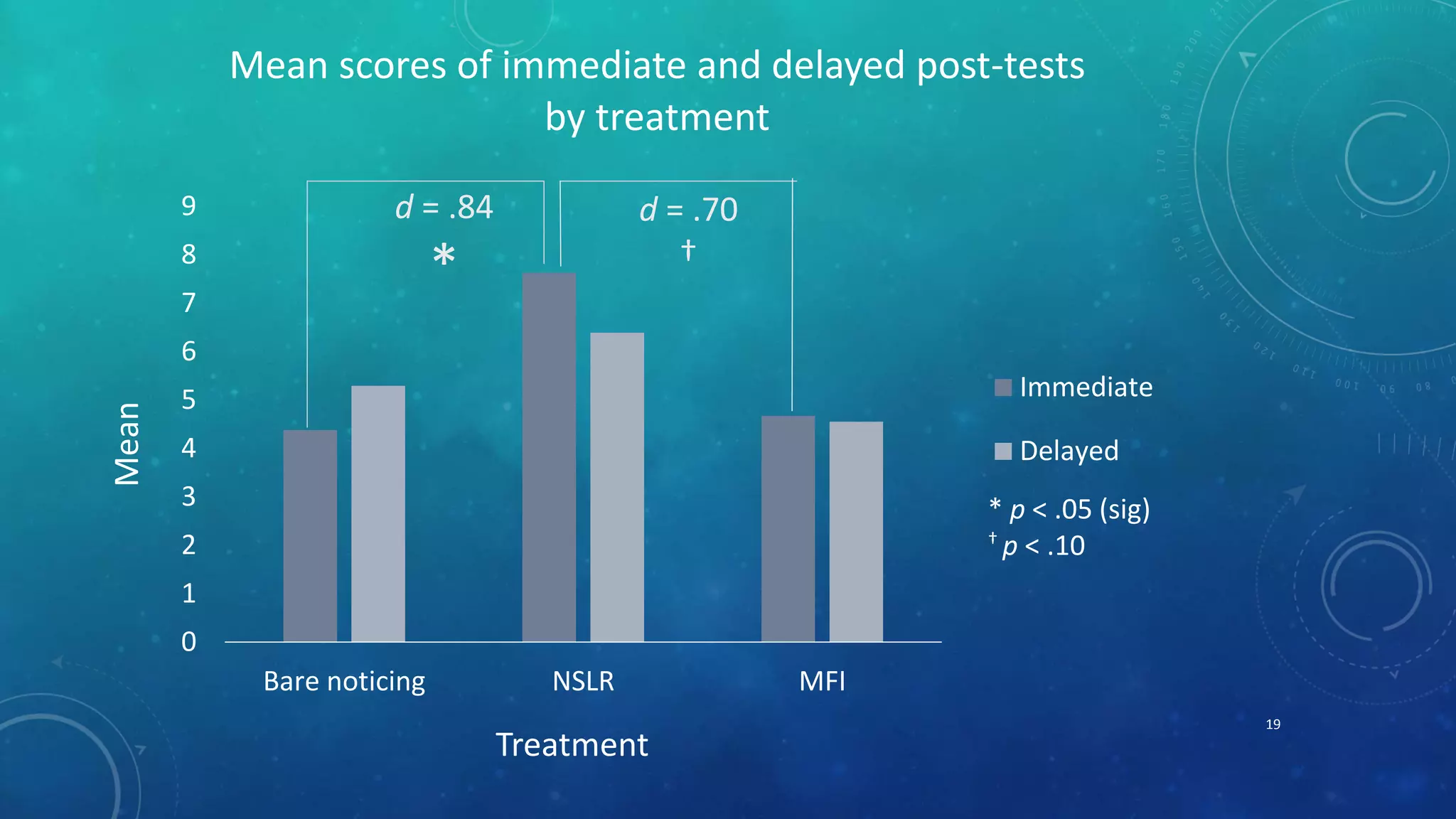

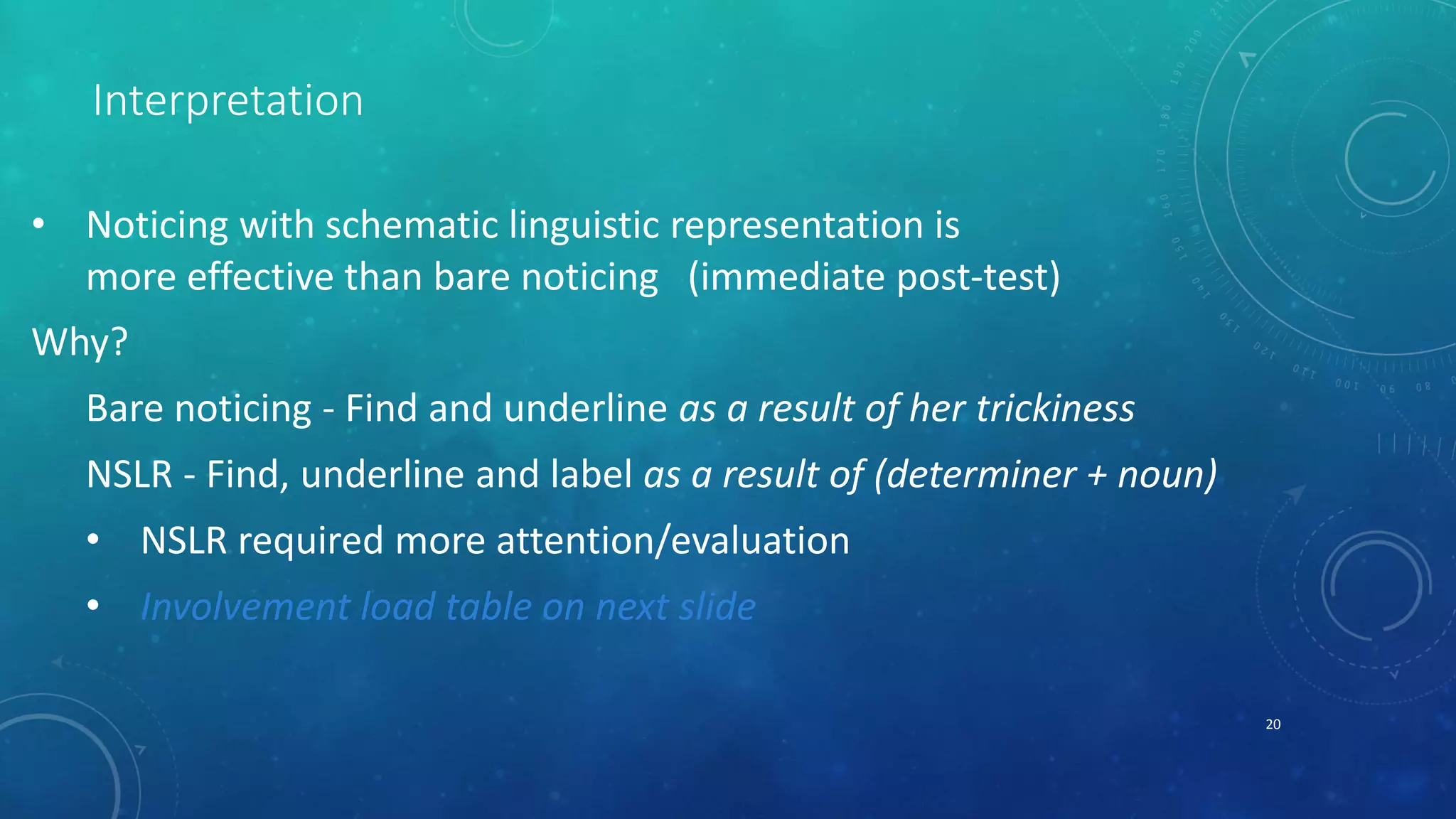

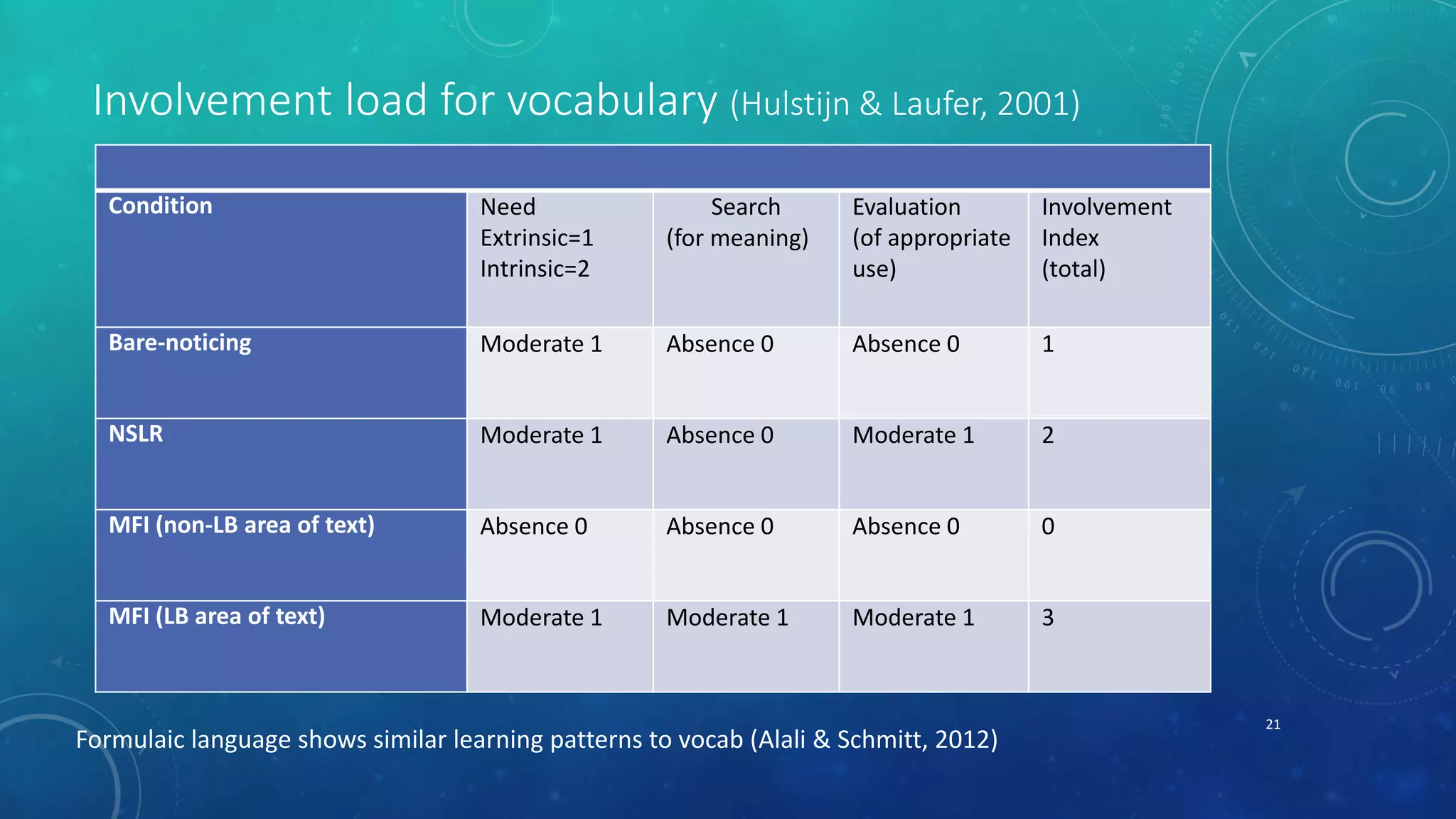

The document discusses the importance of lexical bundles in language learning, highlighting that native speakers acquire them through extensive exposure while second language learners face challenges due to limited exposure. It presents interventions for educators to enhance the learning process, including textbook exercises and noticing strategies. The study conducted tests on Japanese second language learners to evaluate methods of noticing lexical bundles, concluding that using schematic linguistic representation is more effective than bare noticing for immediate retention, although the advantage diminishes over time without rehearsal.