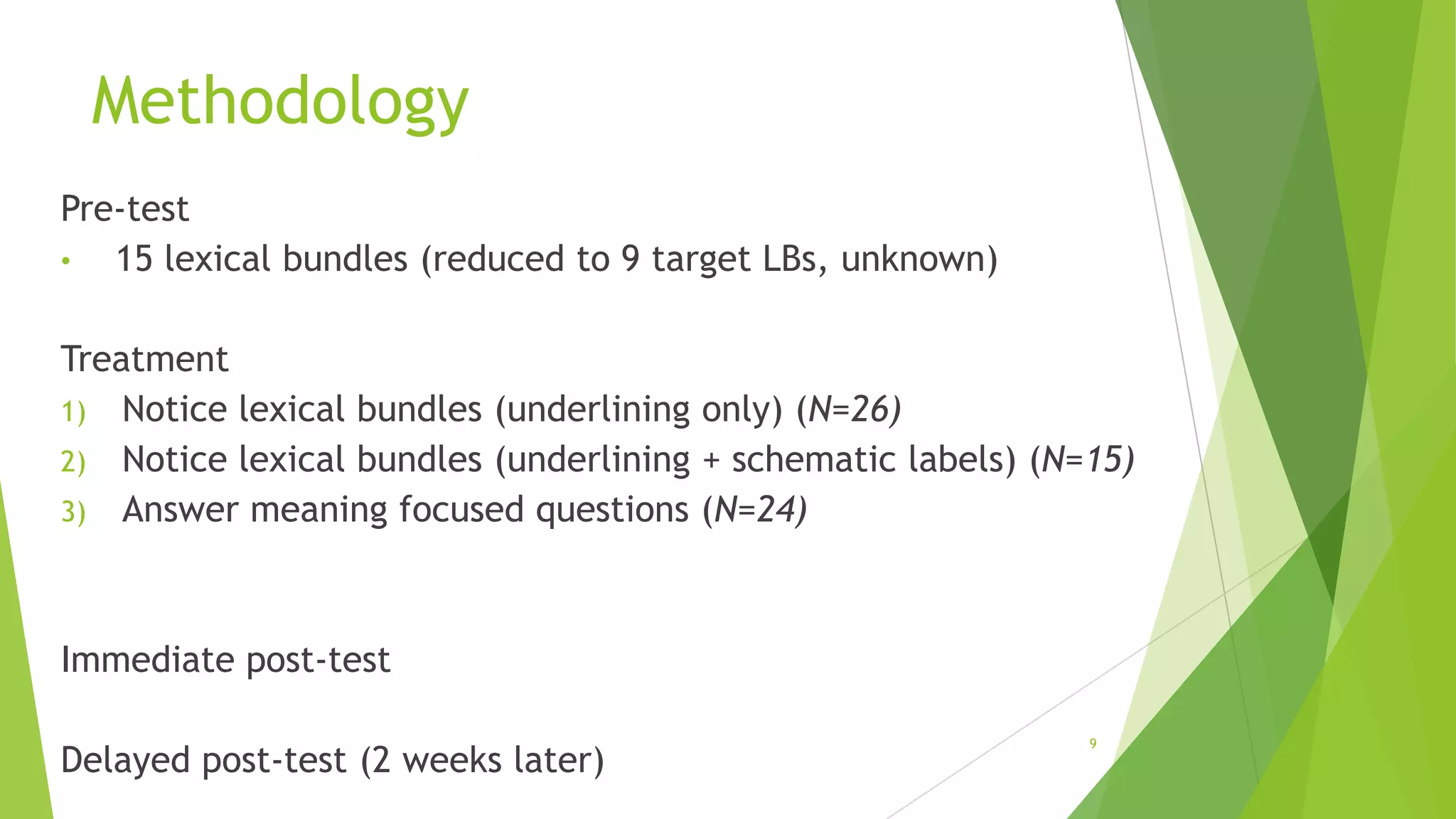

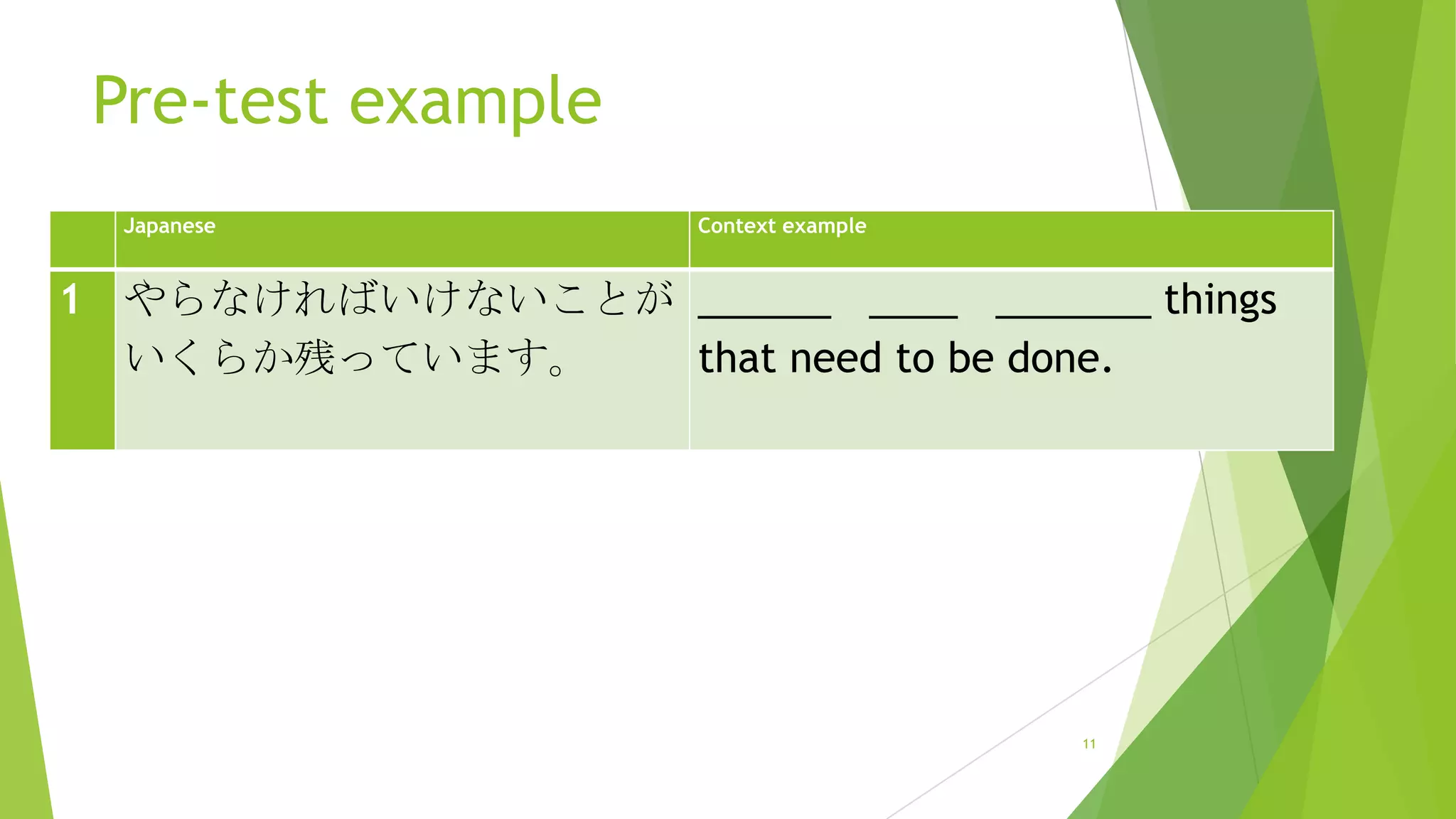

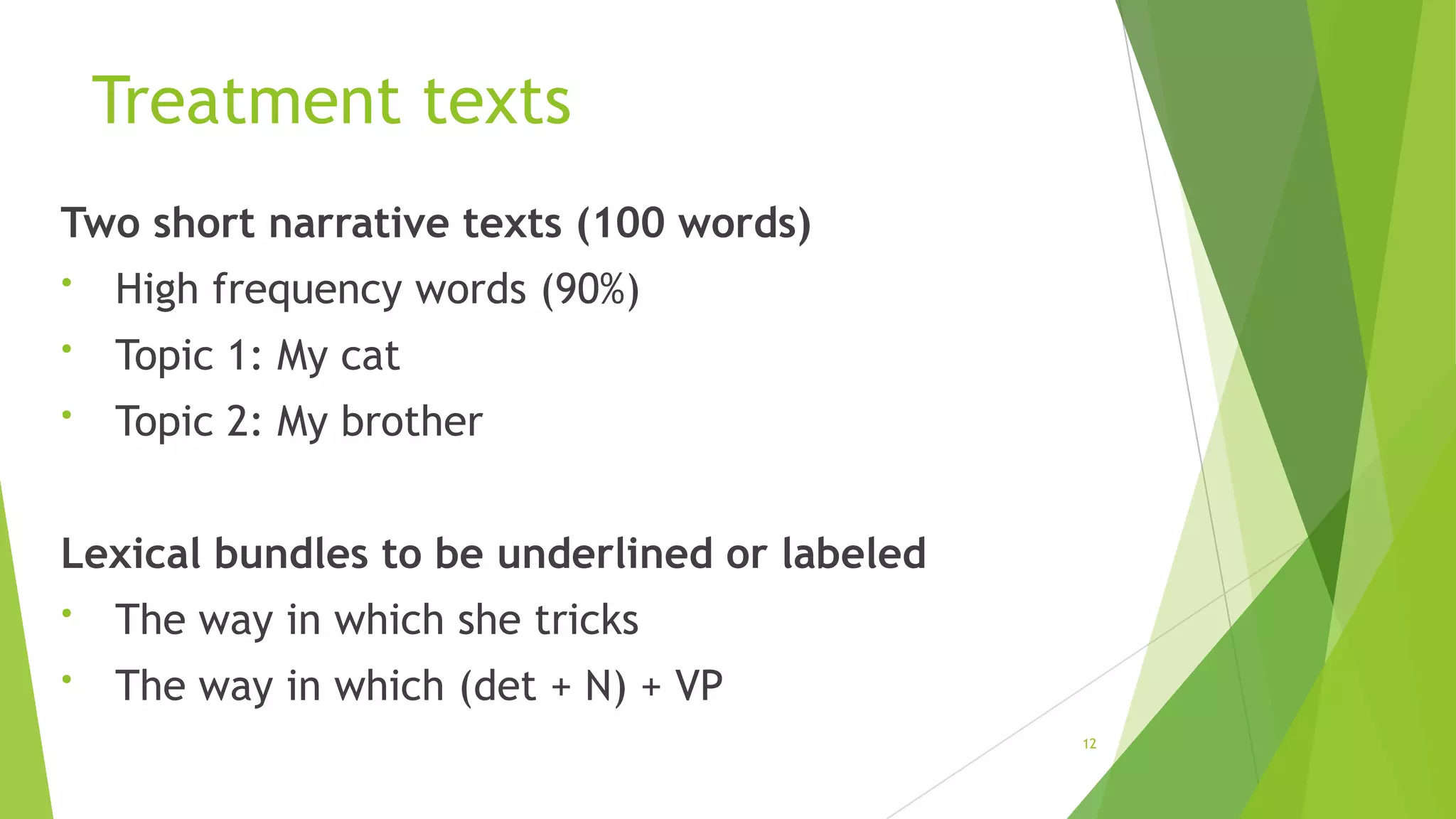

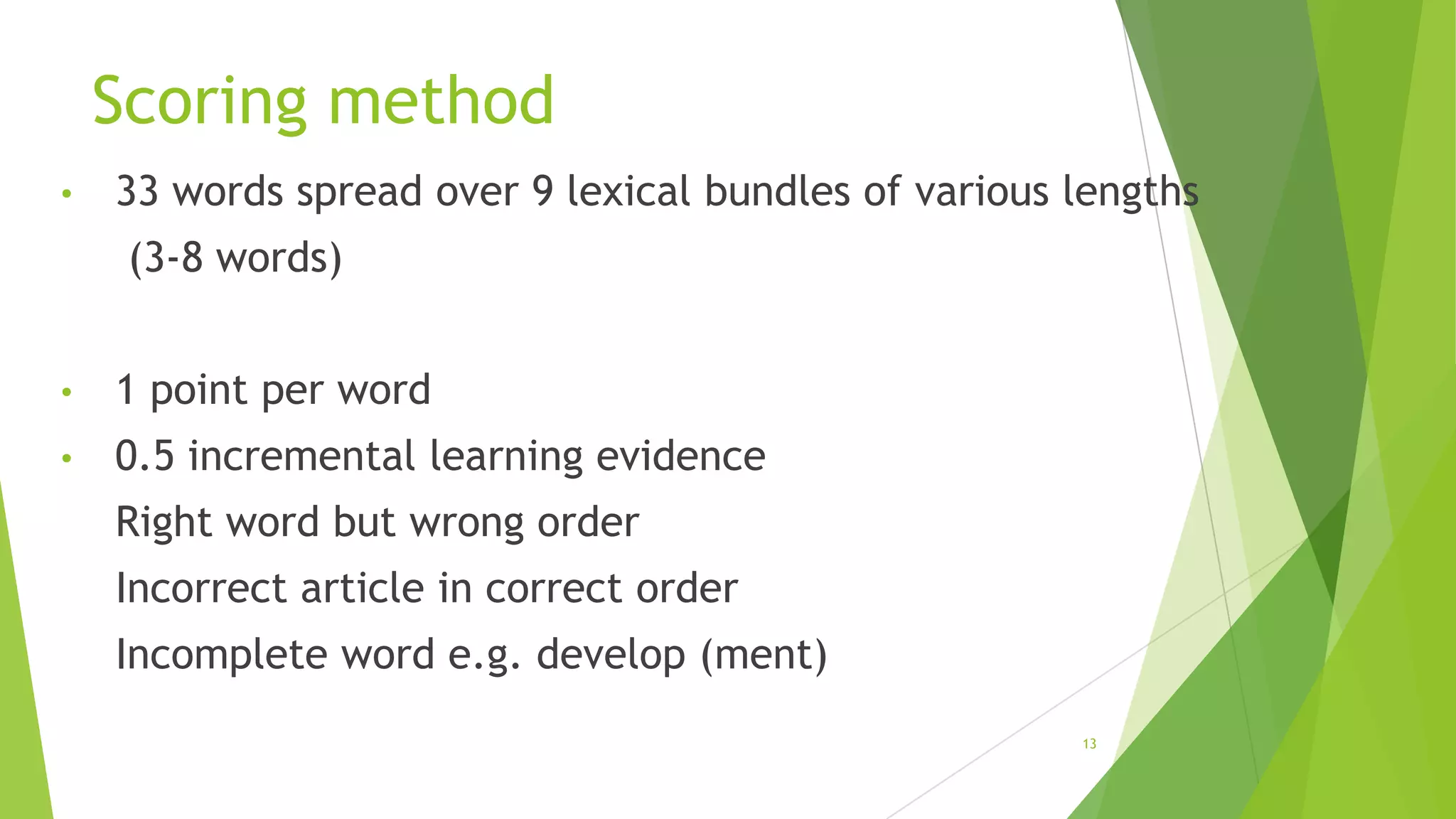

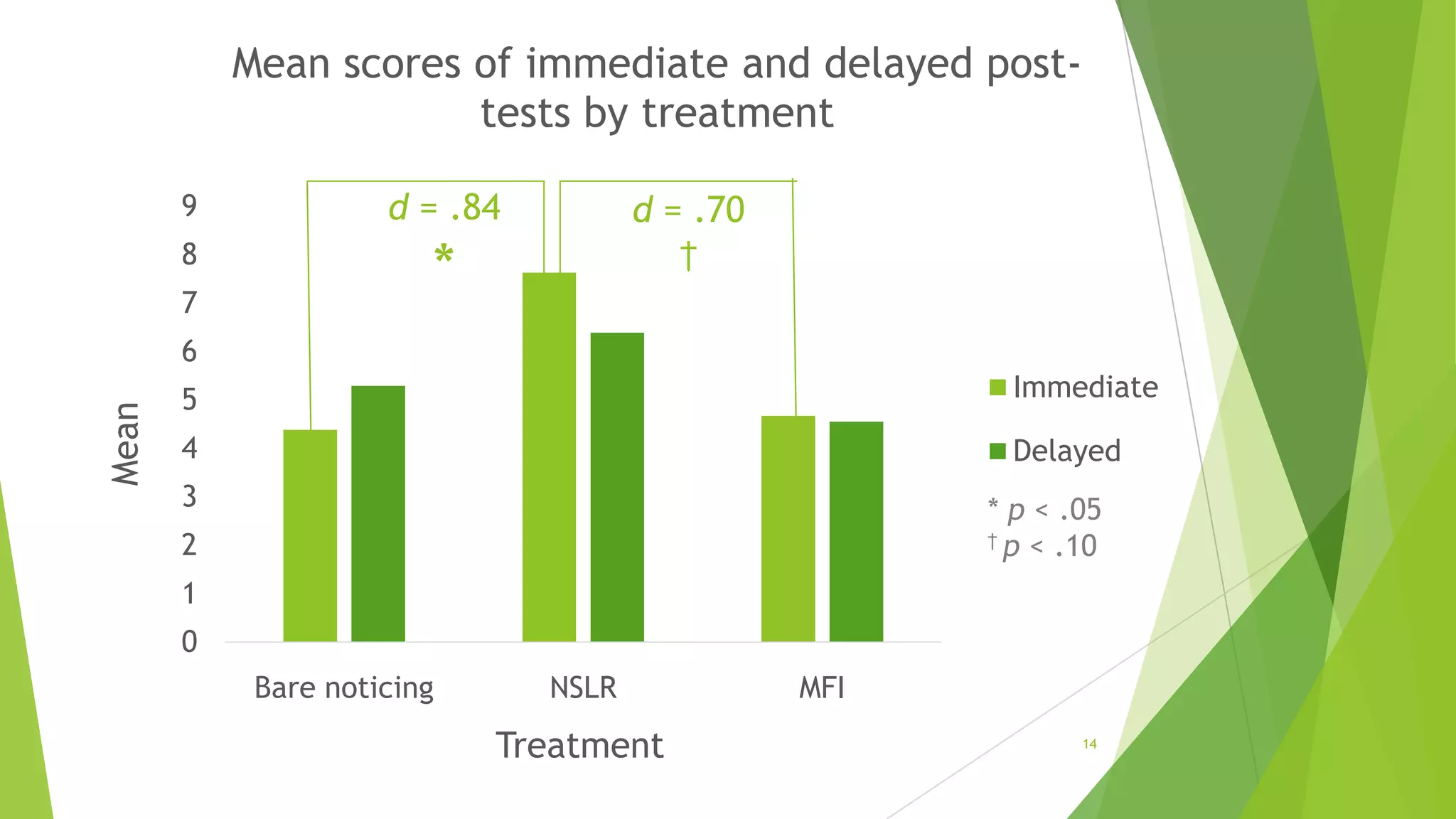

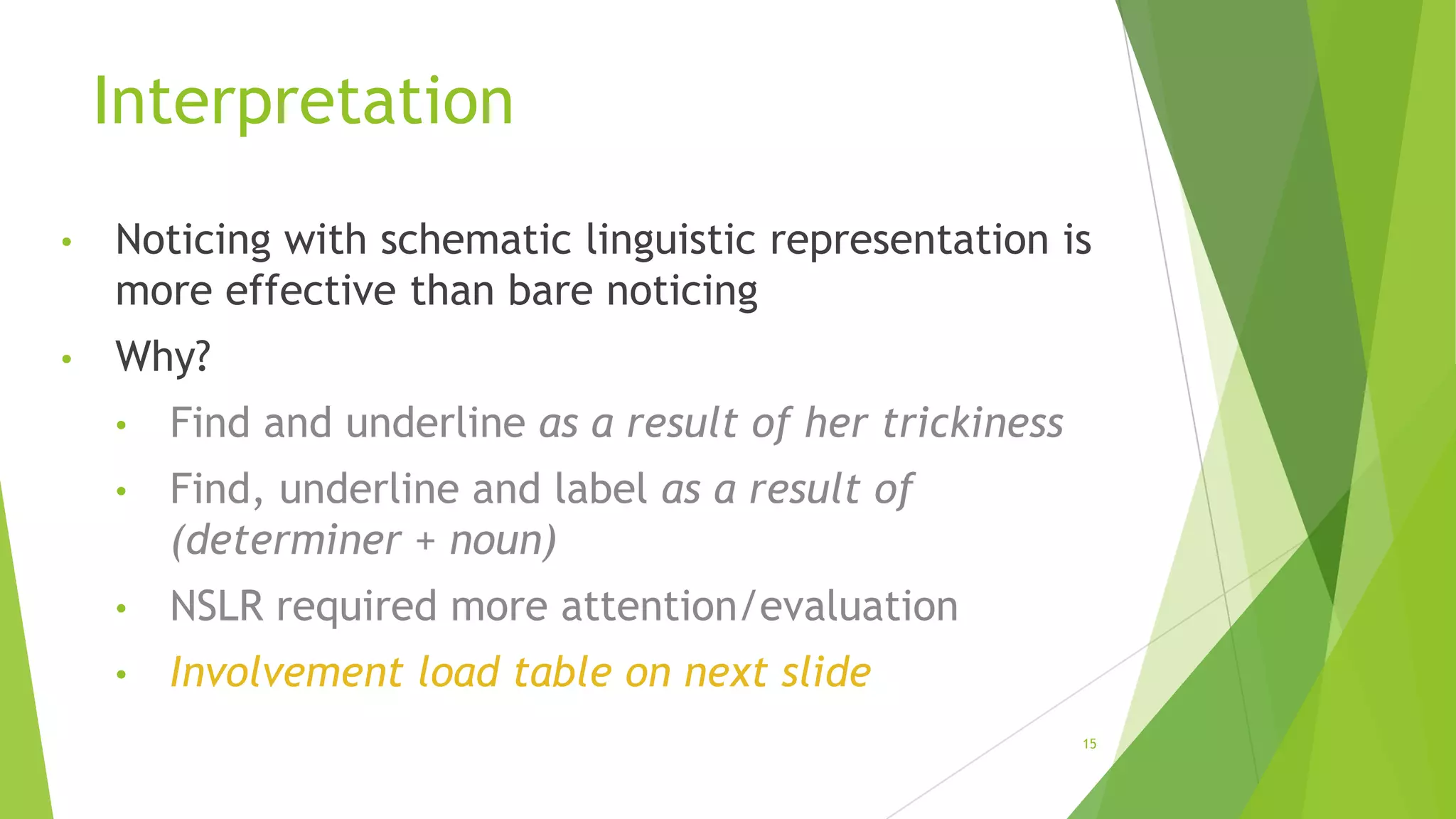

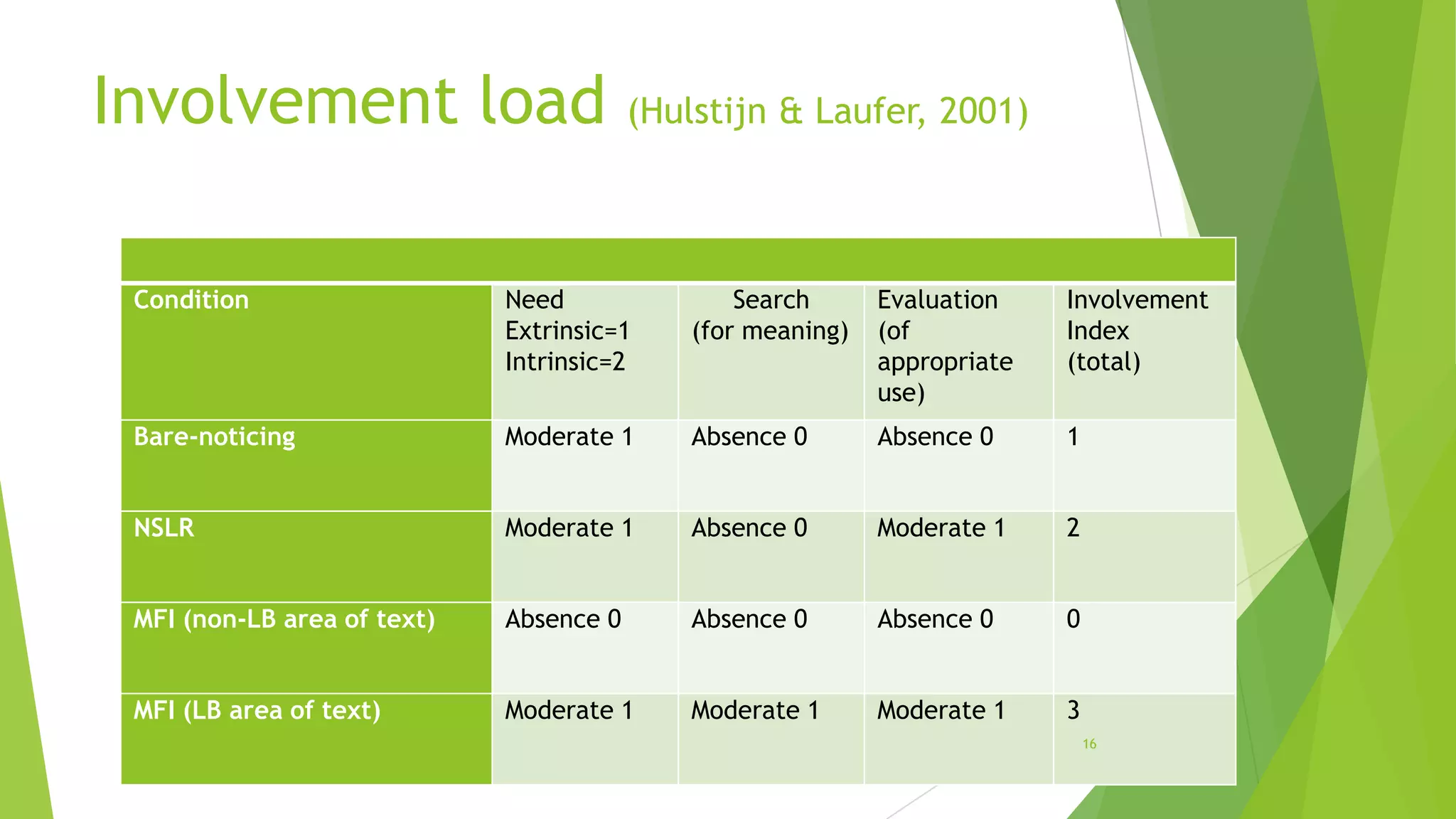

The document presents research on the effectiveness of using schematic linguistic representation for teaching lexical bundles to non-major EFL learners in Japan. It outlines a study methodology that includes pre-testing, treatments involving different noticing strategies, and post-tests to evaluate learning outcomes. Findings suggest that the approach enhances the learners' ability to produce lexical bundles compared to traditional methods.