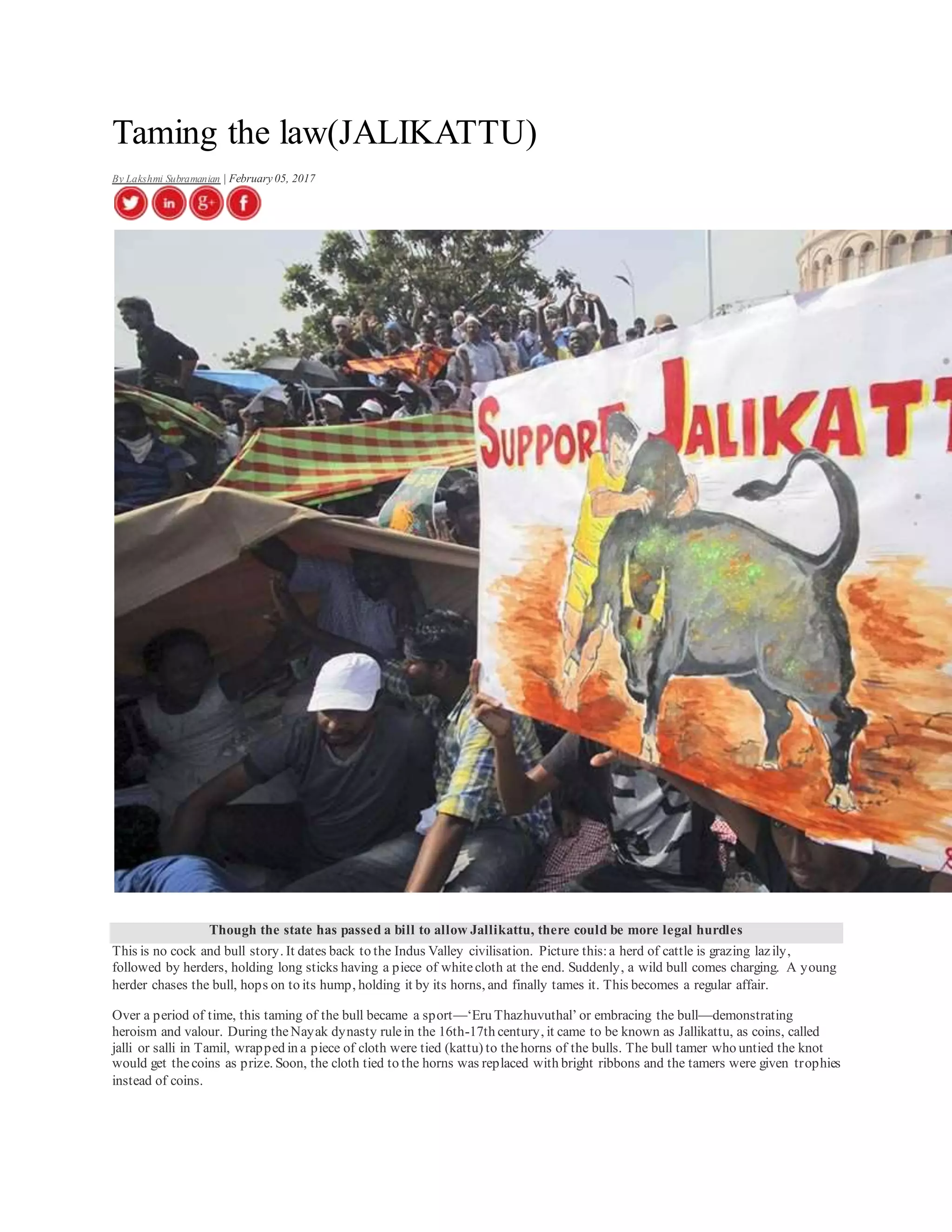

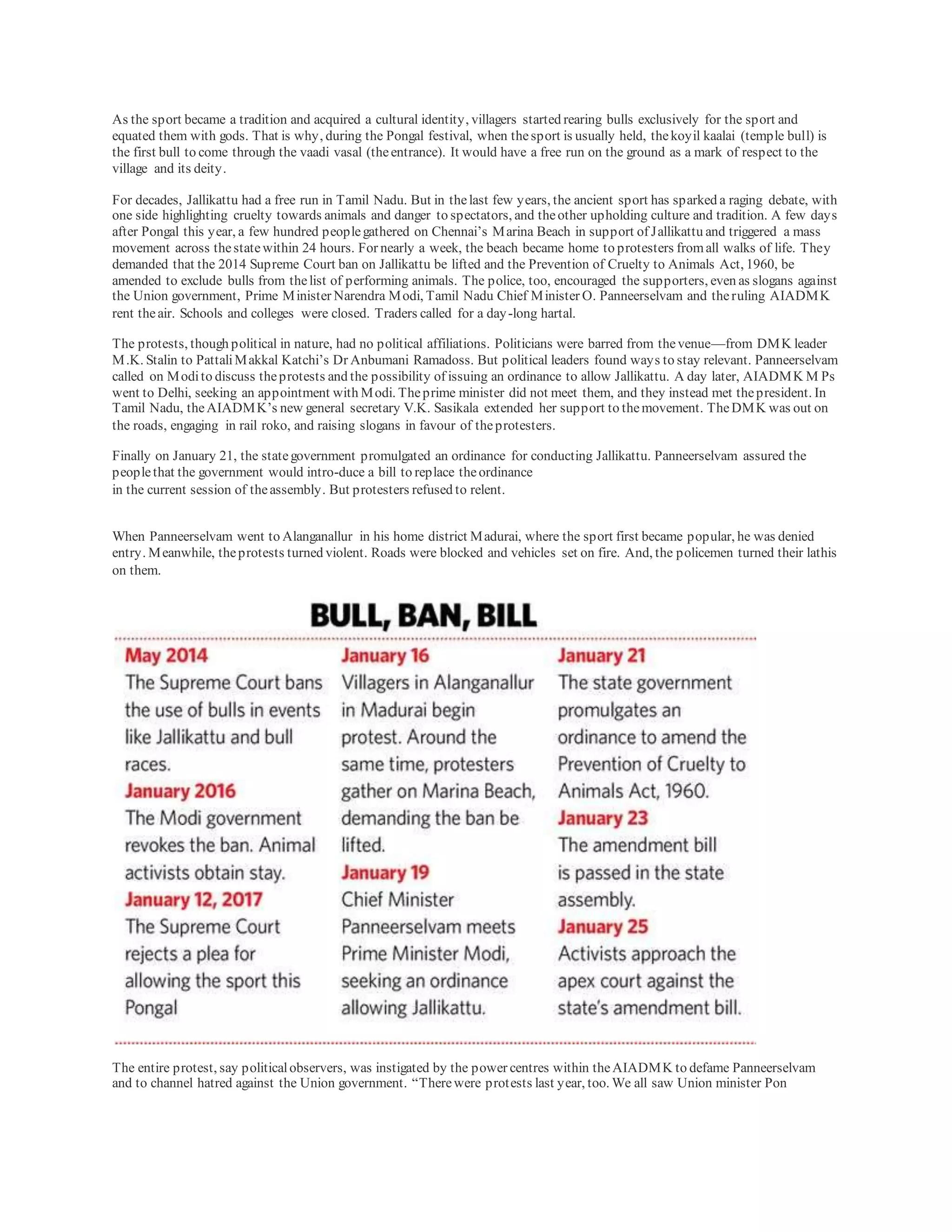

The document discusses the historical and cultural significance of the sport jallikattu in Tamil Nadu, which has faced legal challenges and backlash due to concerns about animal cruelty. Following protests advocating for the sport, the Tamil Nadu government implemented an ordinance and proposed a bill to allow jallikattu, claiming the amendments address concerns about animal welfare. However, there is uncertainty about the bill's potential to withstand legal scrutiny, as prior regulations have faced challenges in court.