This document introduces some new concepts available in Fortran 90-2003 compared to Fortran 77, including:

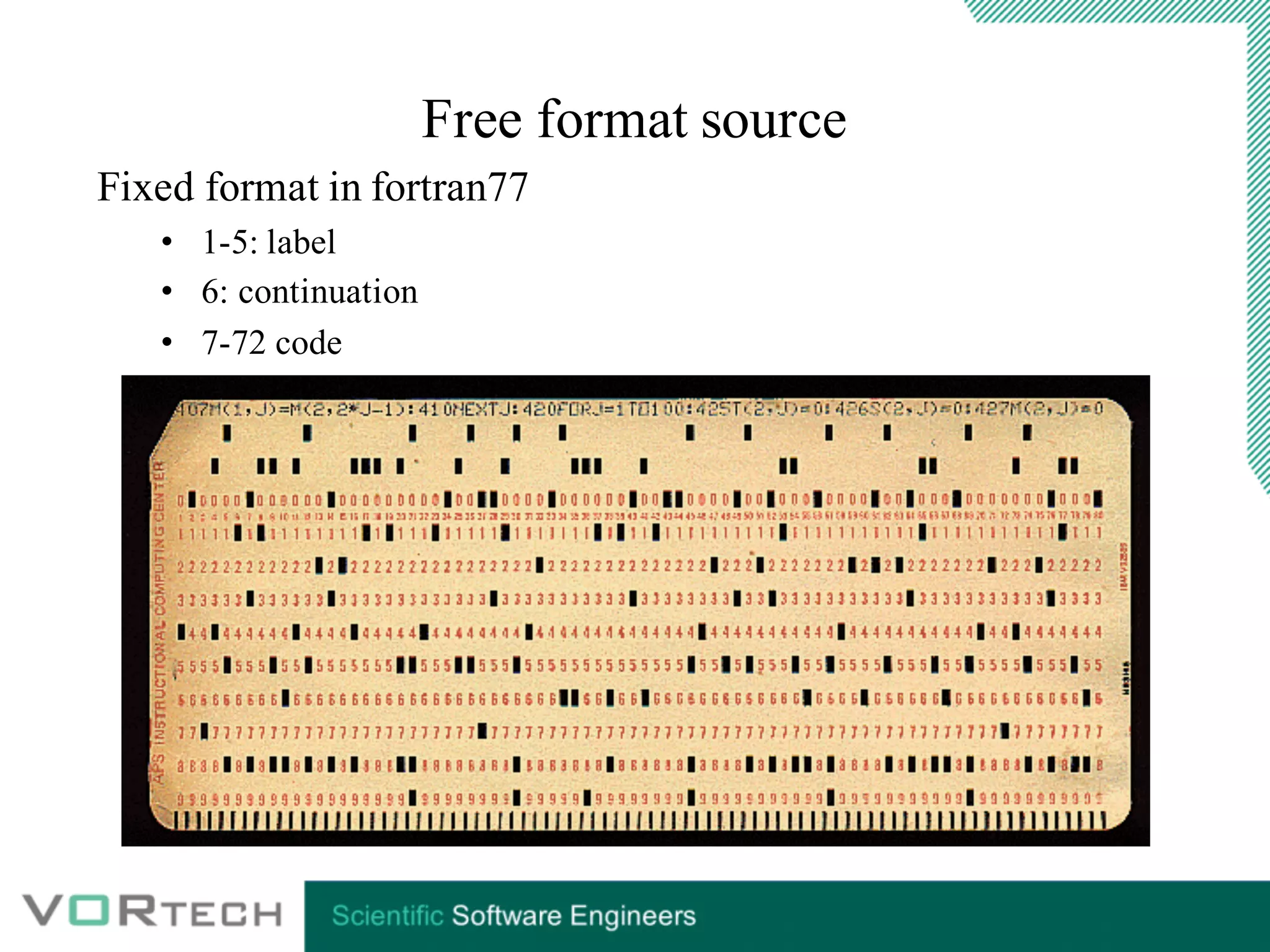

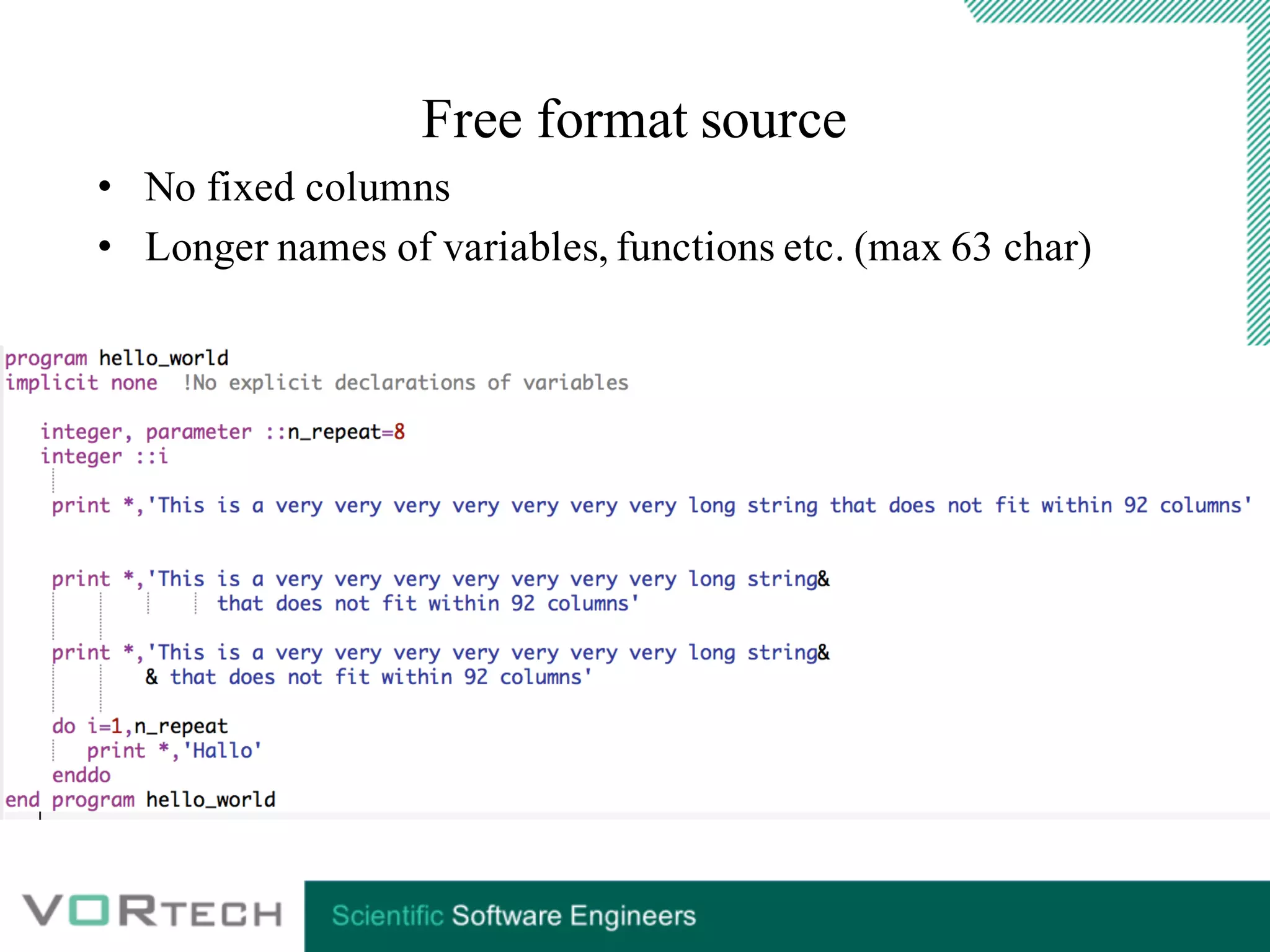

1) Free format source code which removes the need for fixed column formatting.

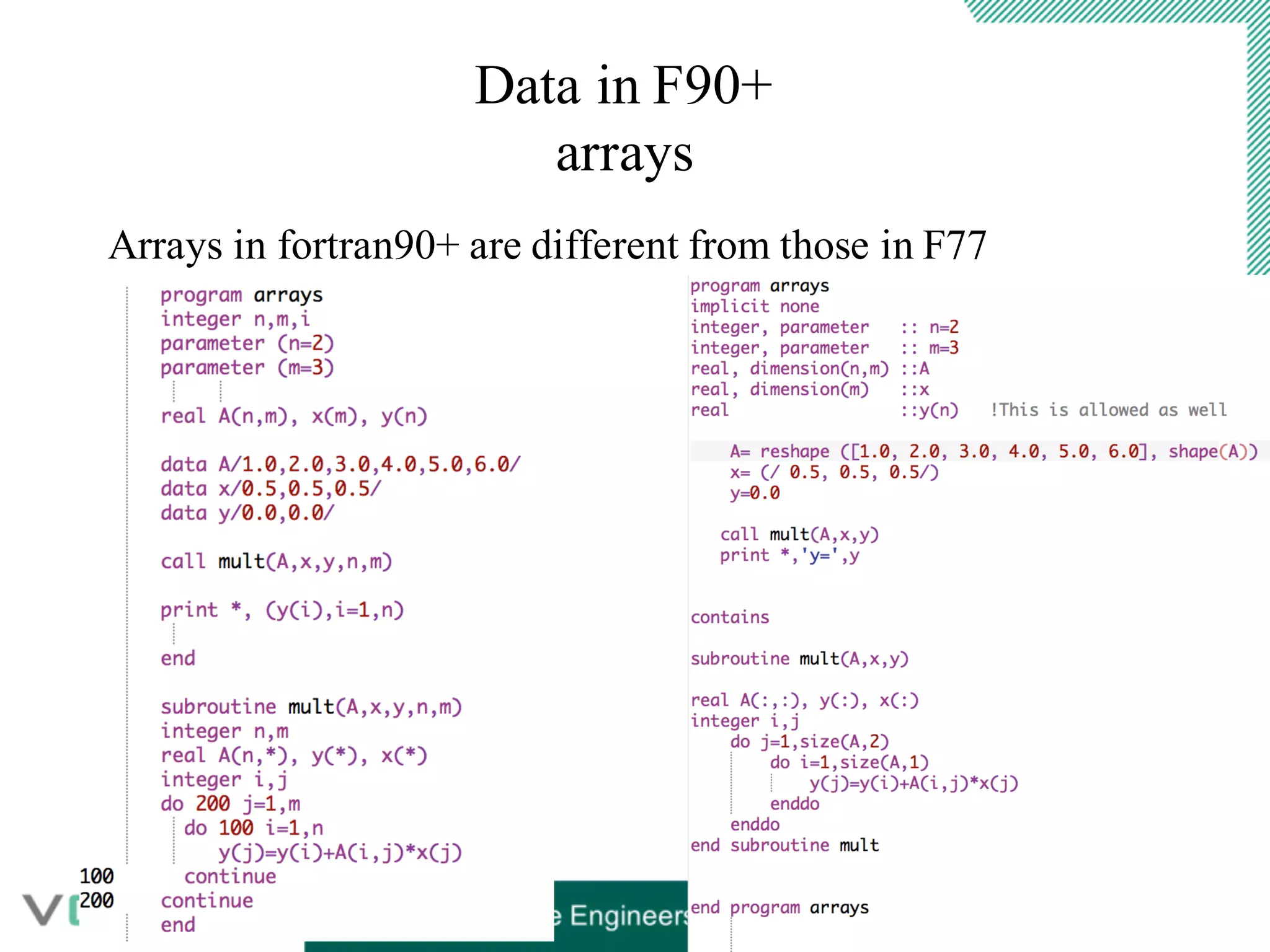

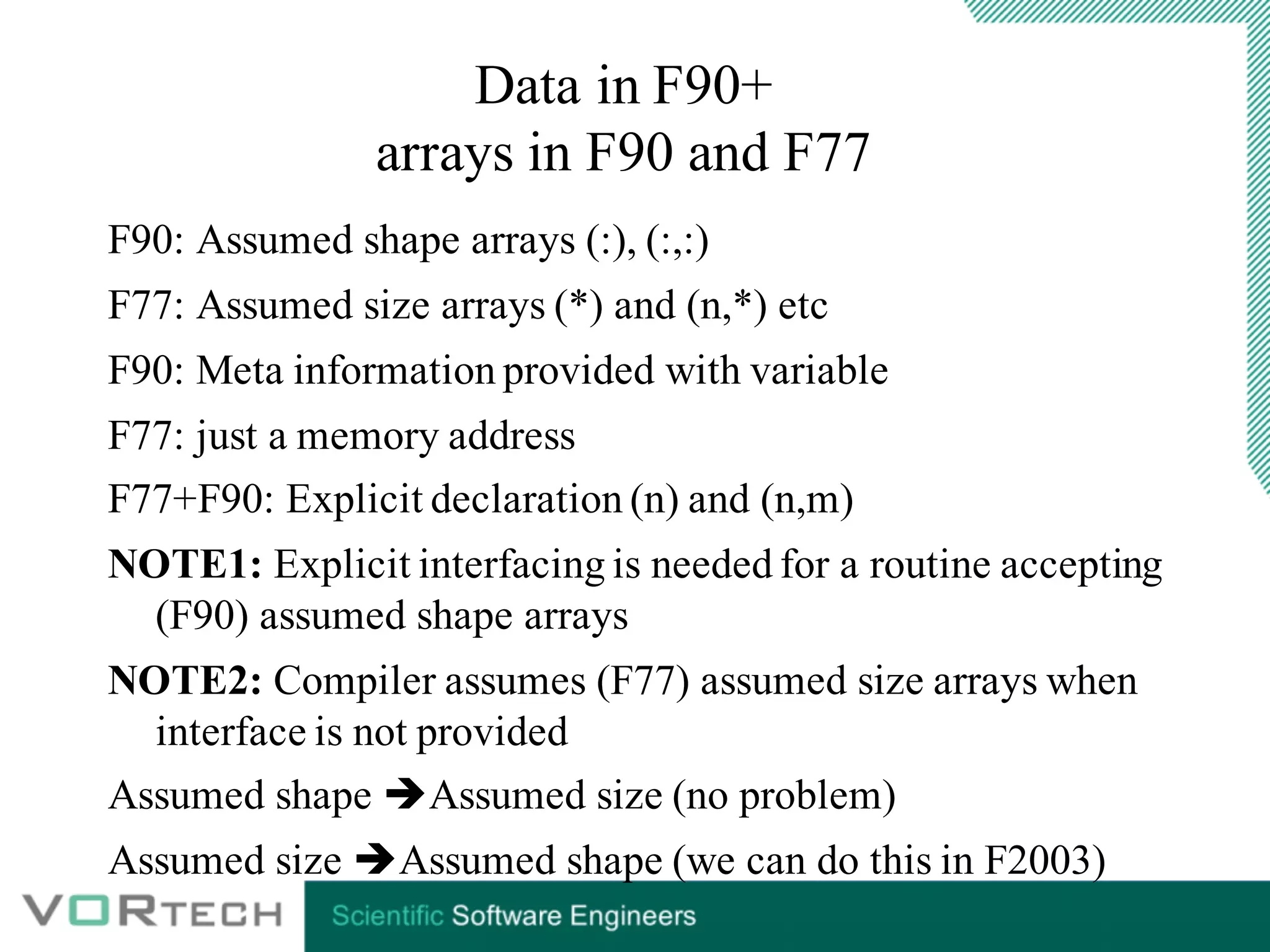

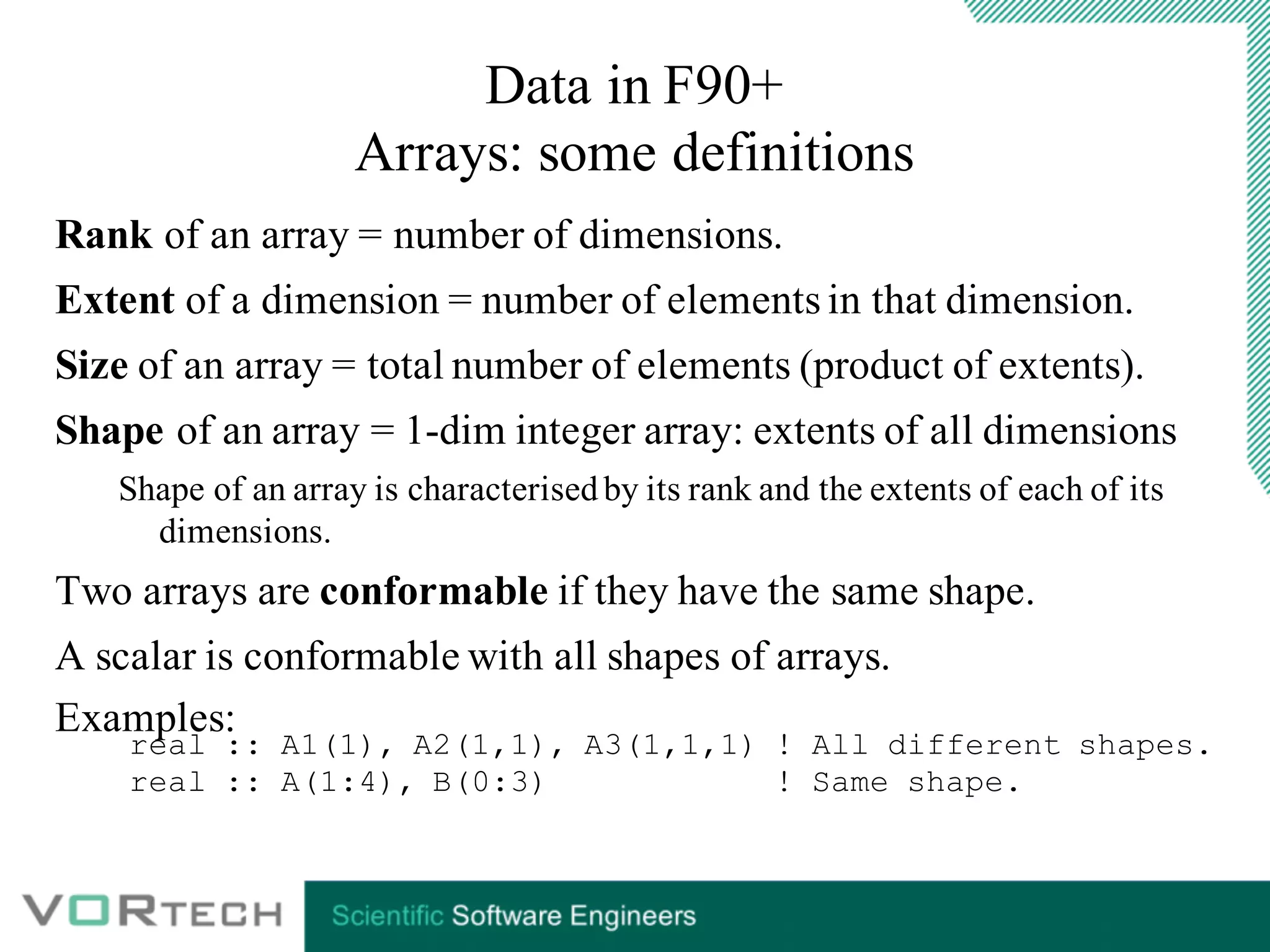

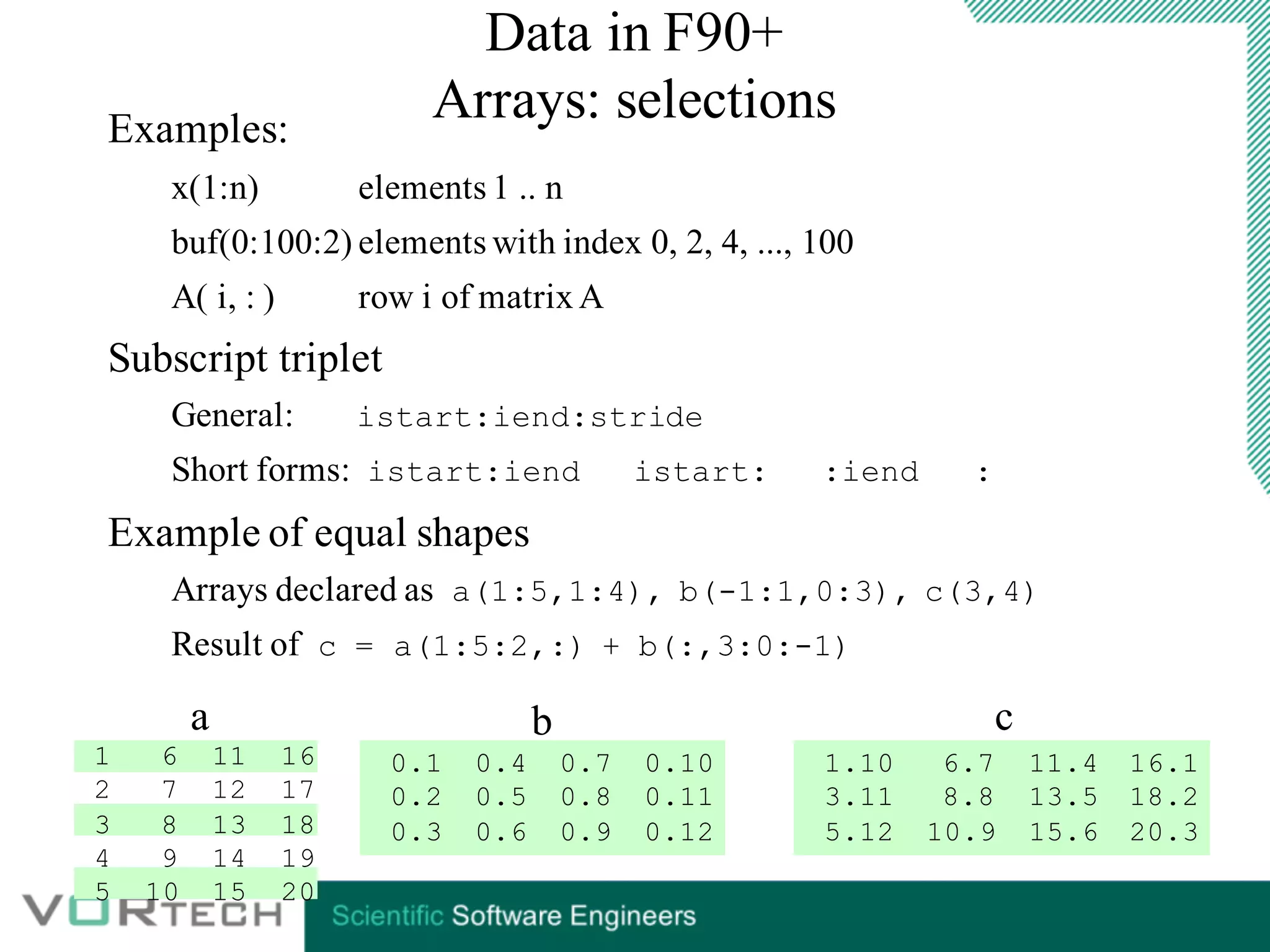

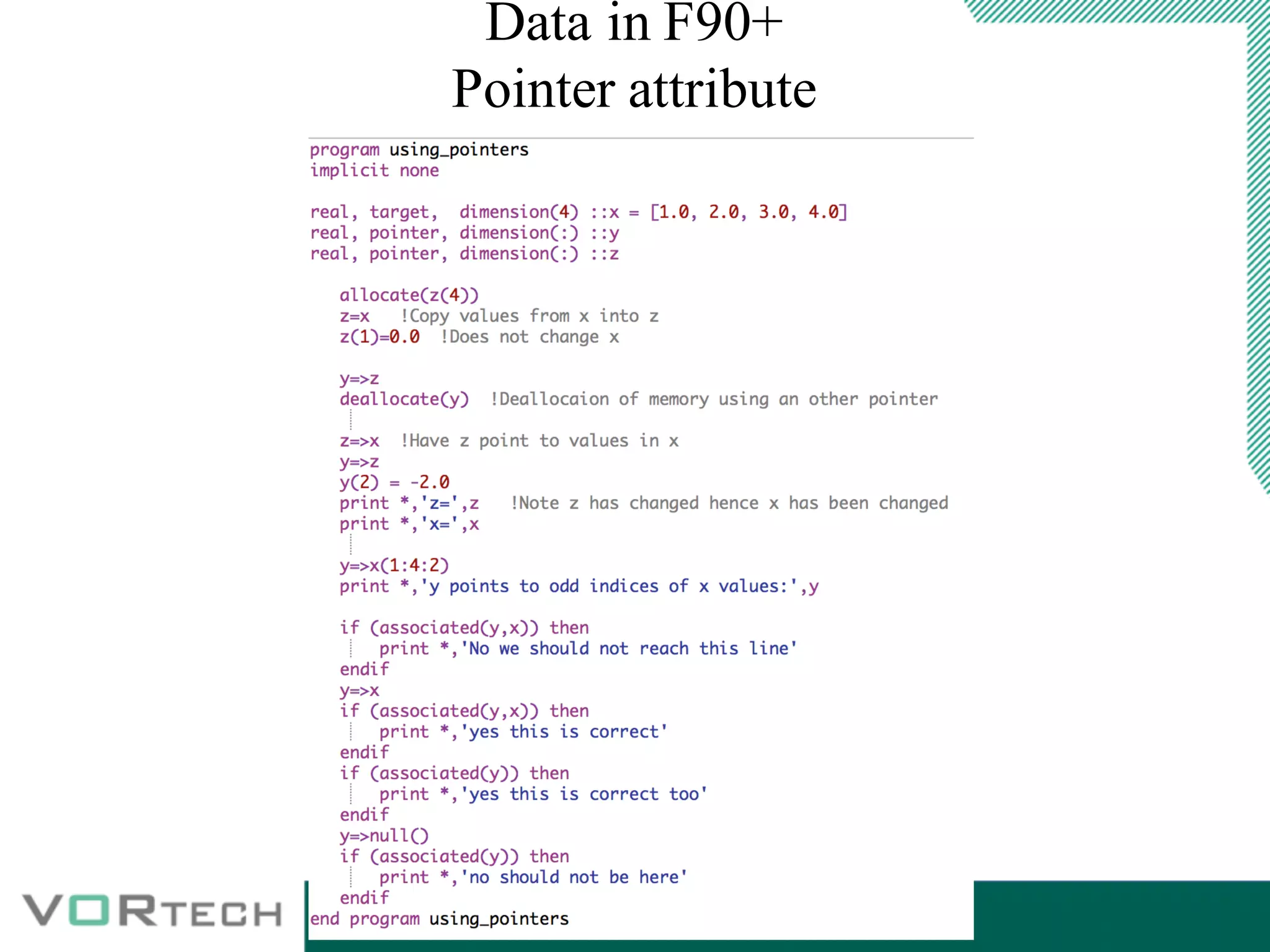

2) New data types like assumed shape arrays which provide meta information about array dimensions, allowing whole array operations.

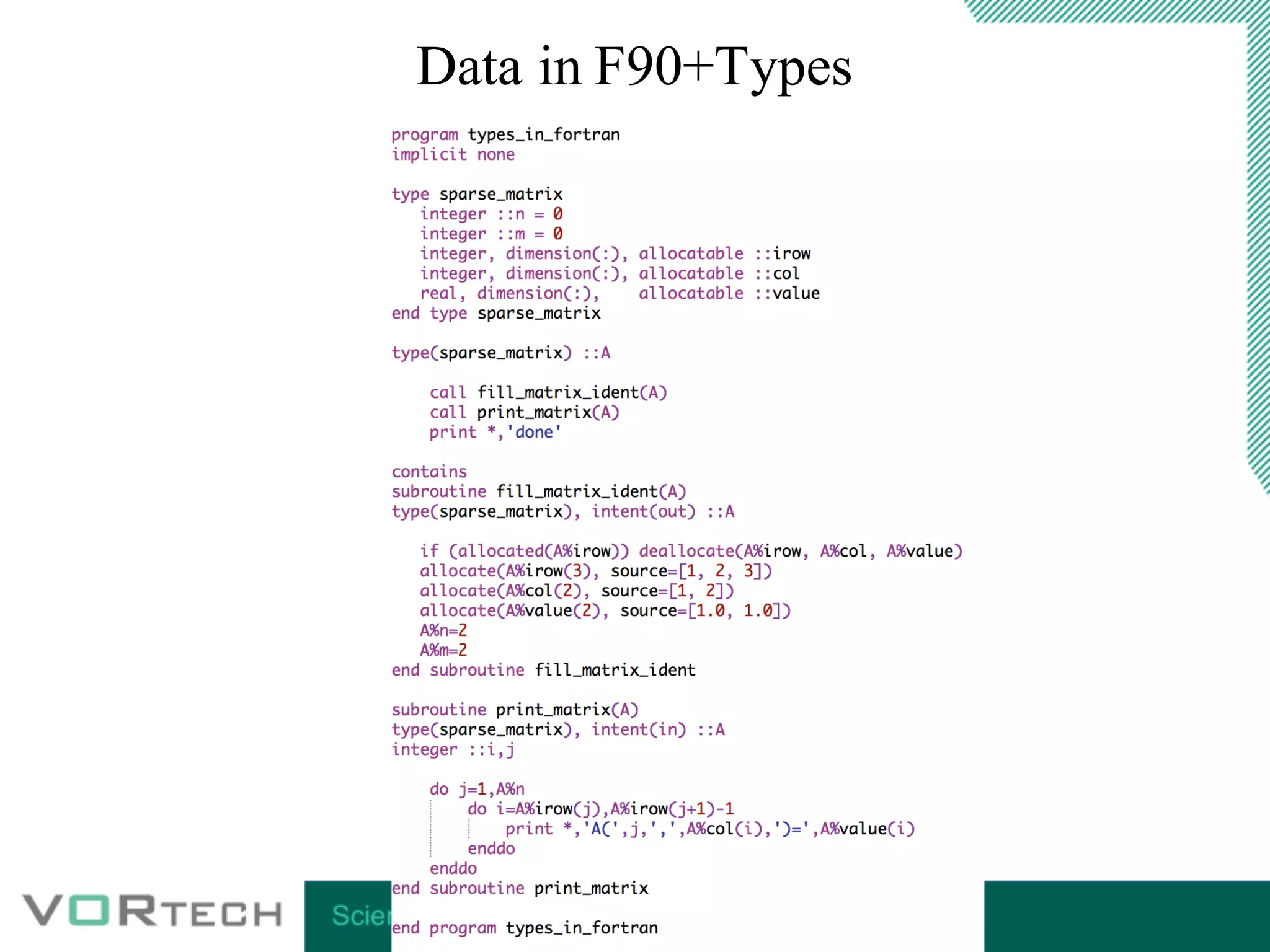

3) Modules which group functionality and avoid name clashes by hiding implementation details.

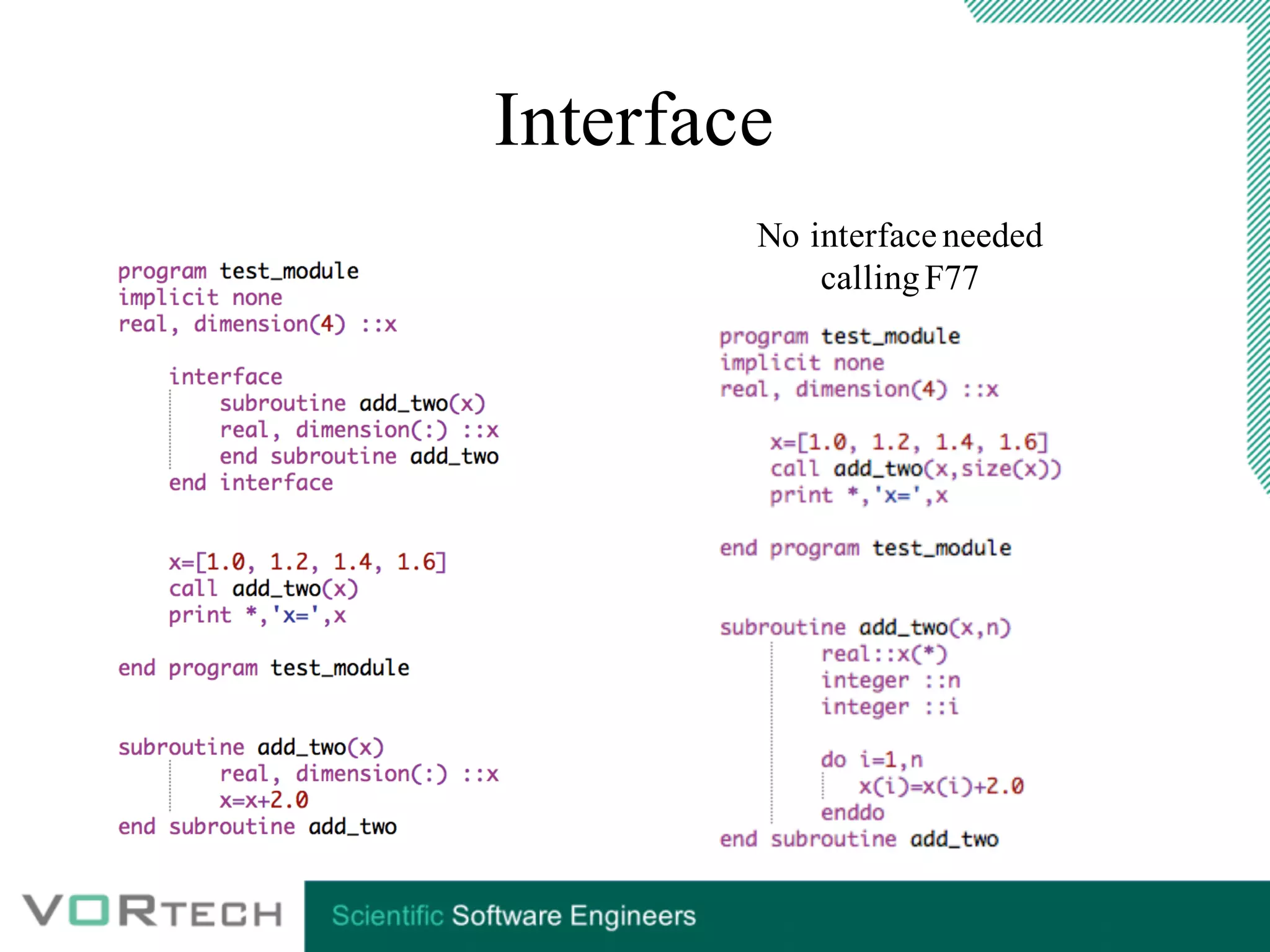

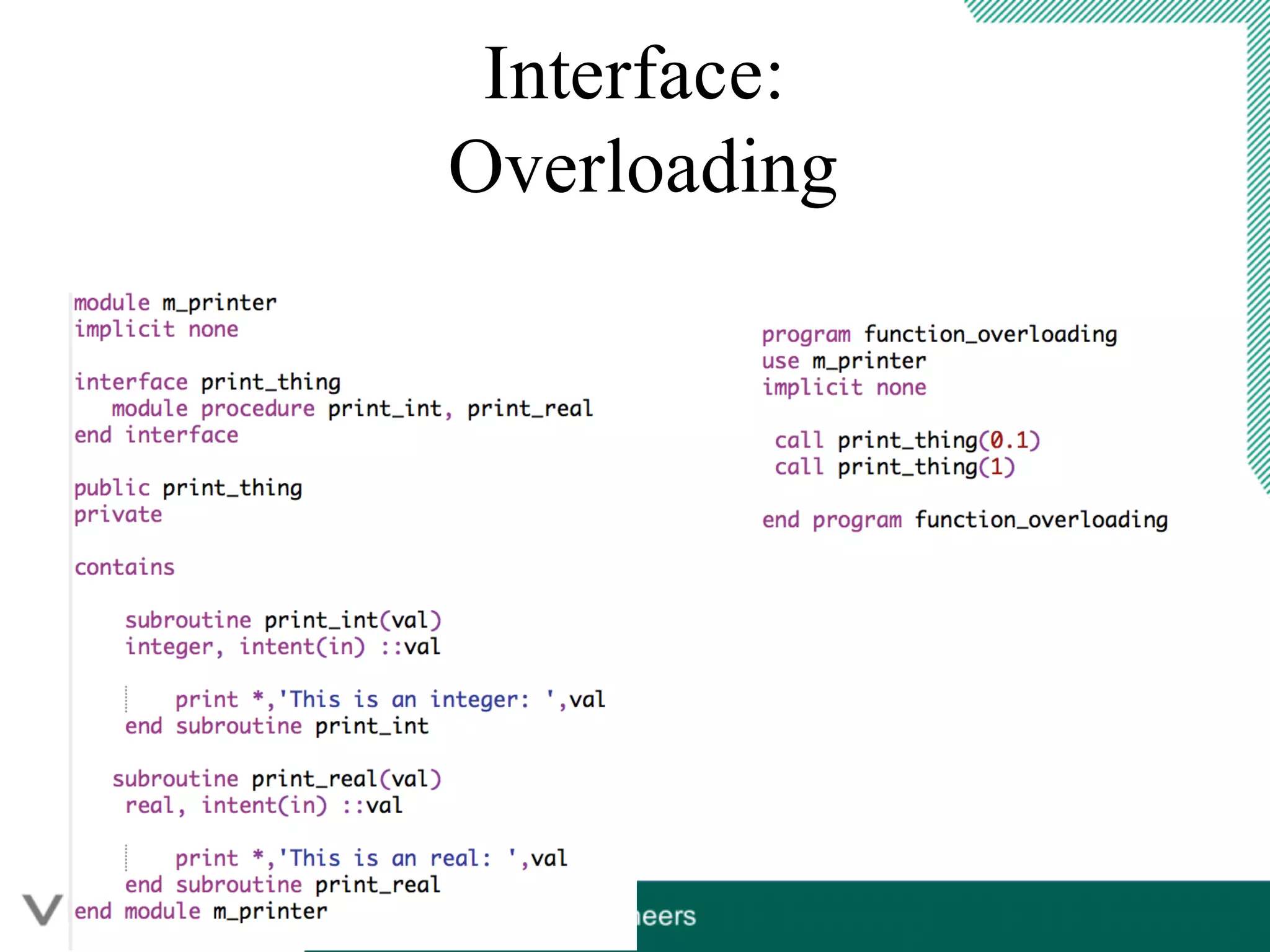

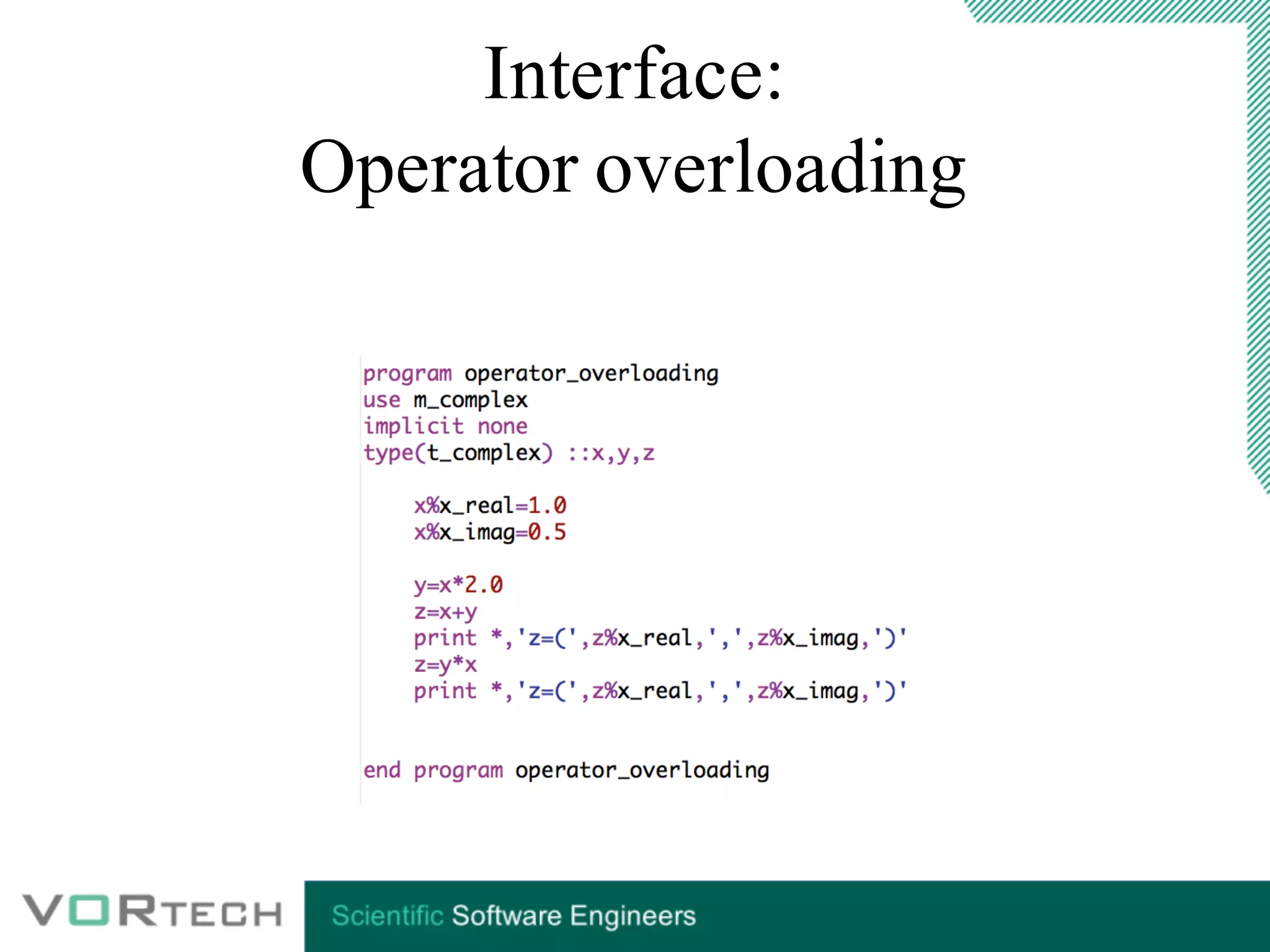

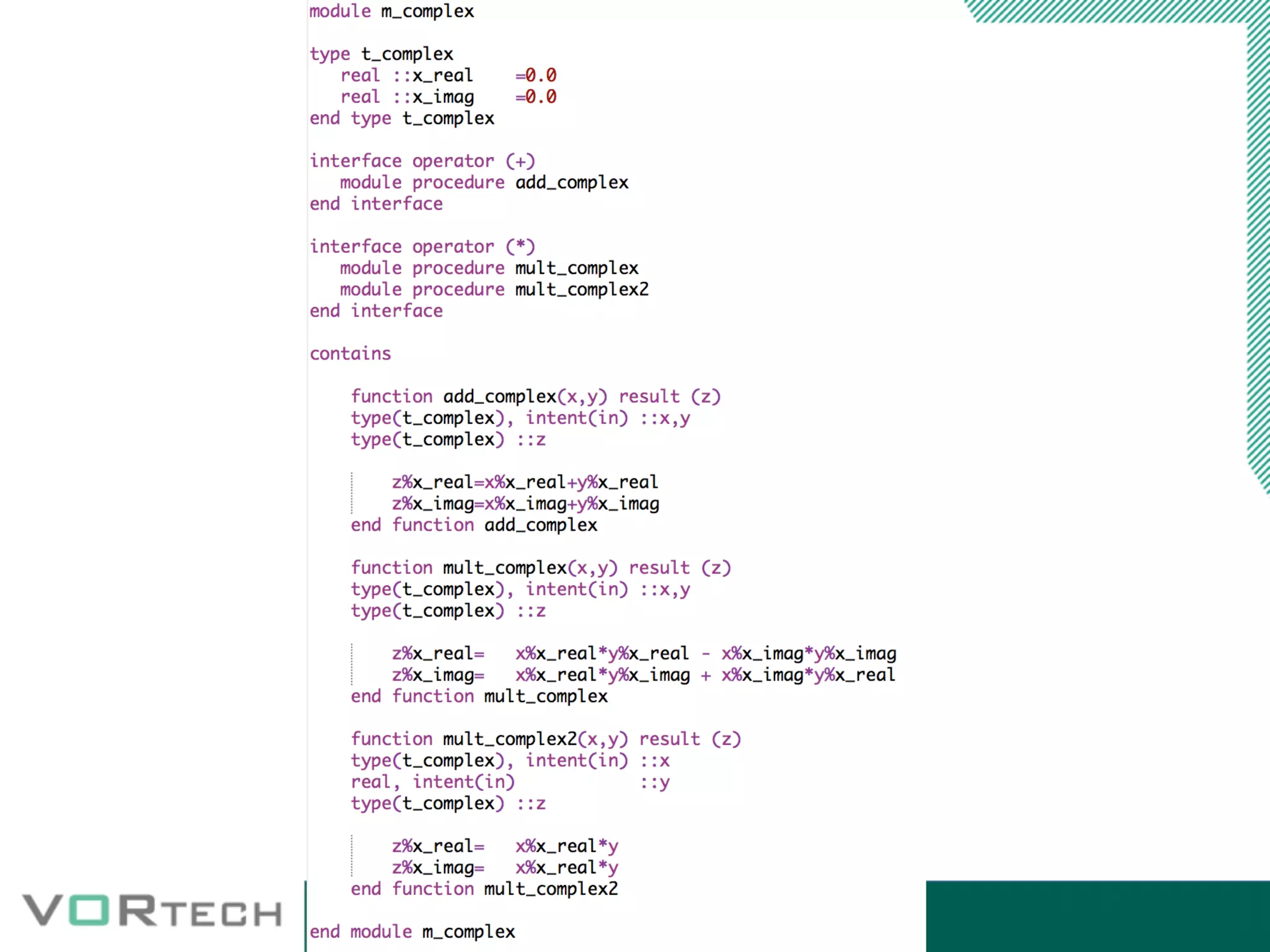

4) Interface blocks which enable operator and function overloading.

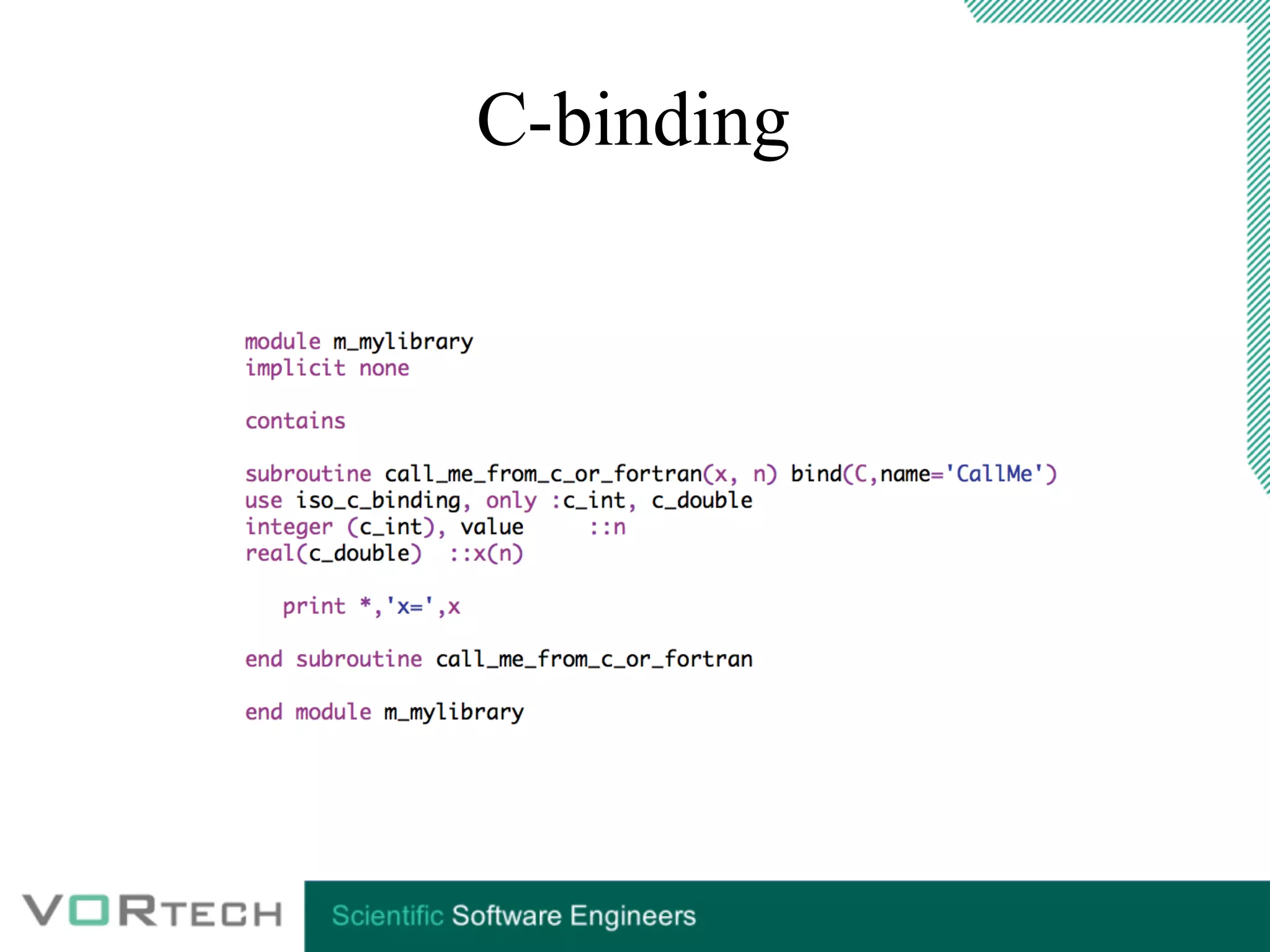

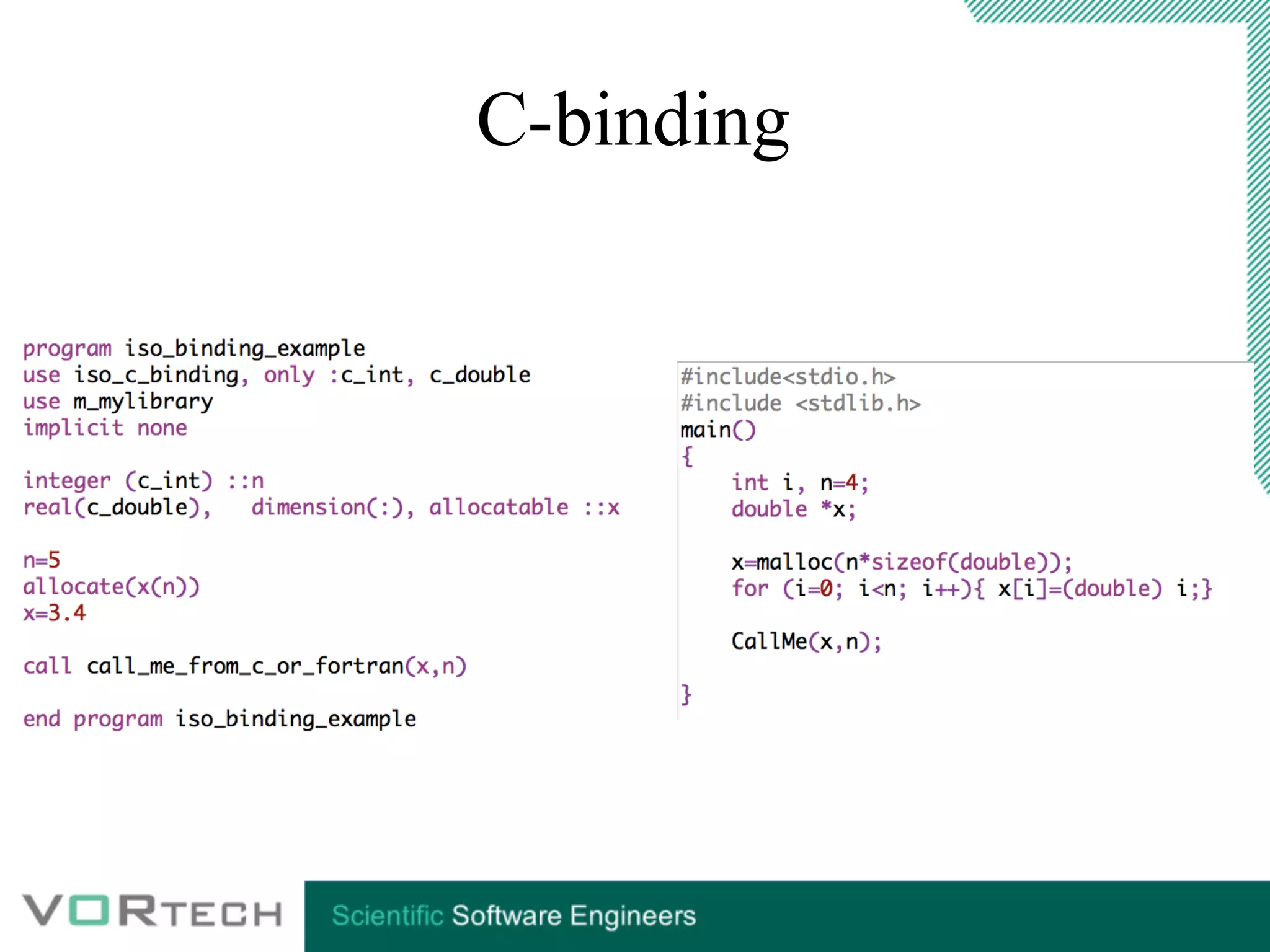

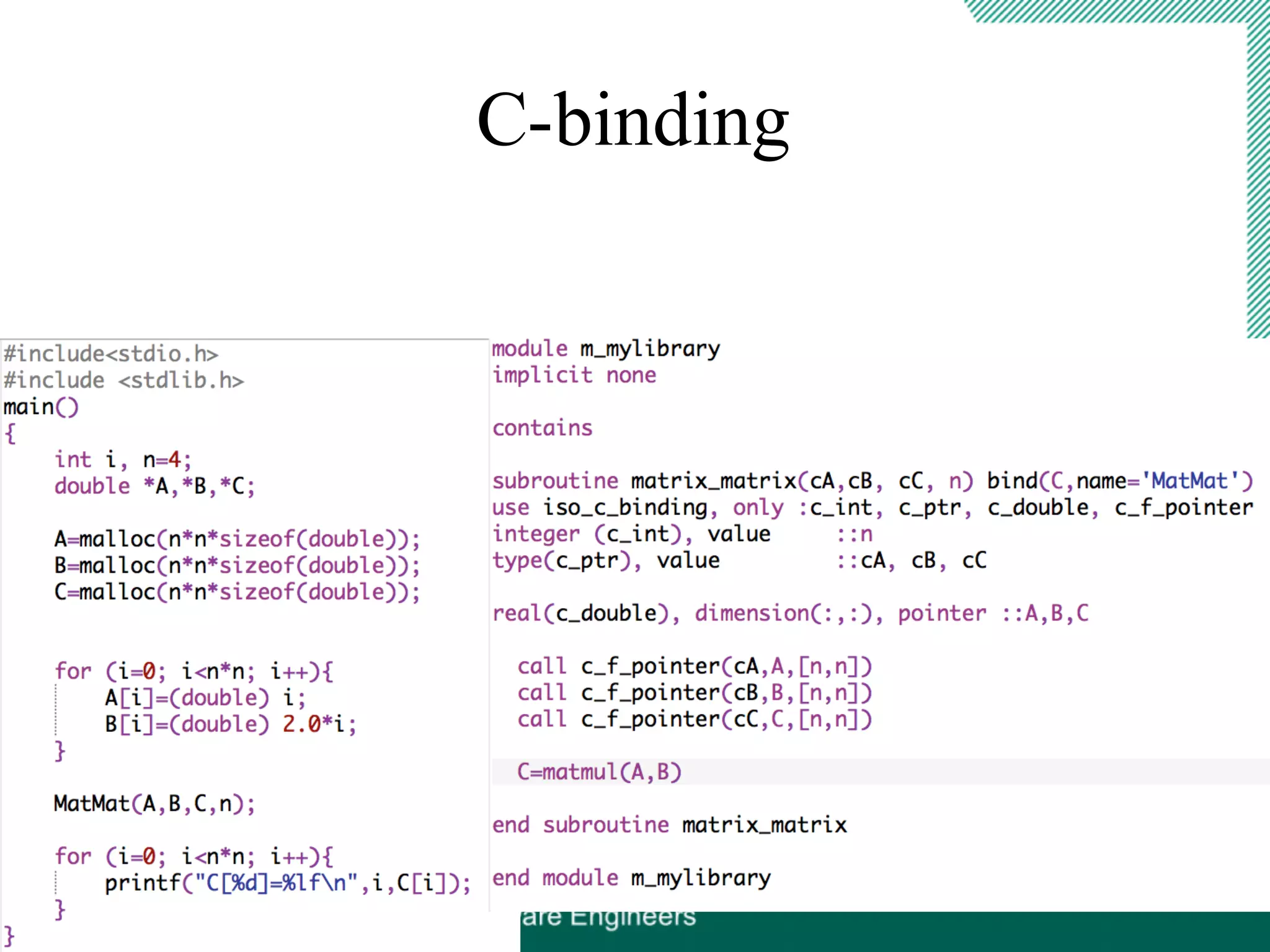

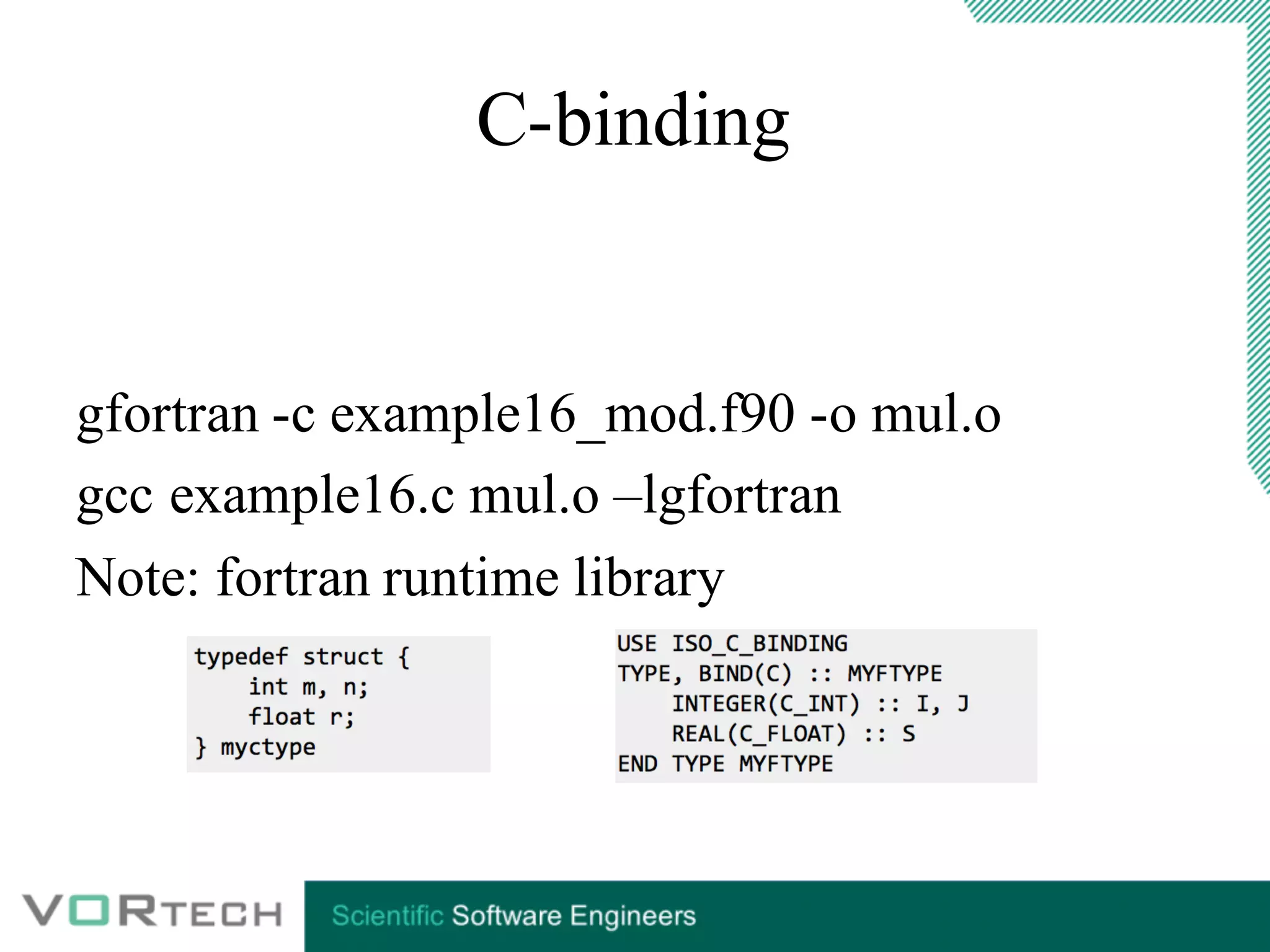

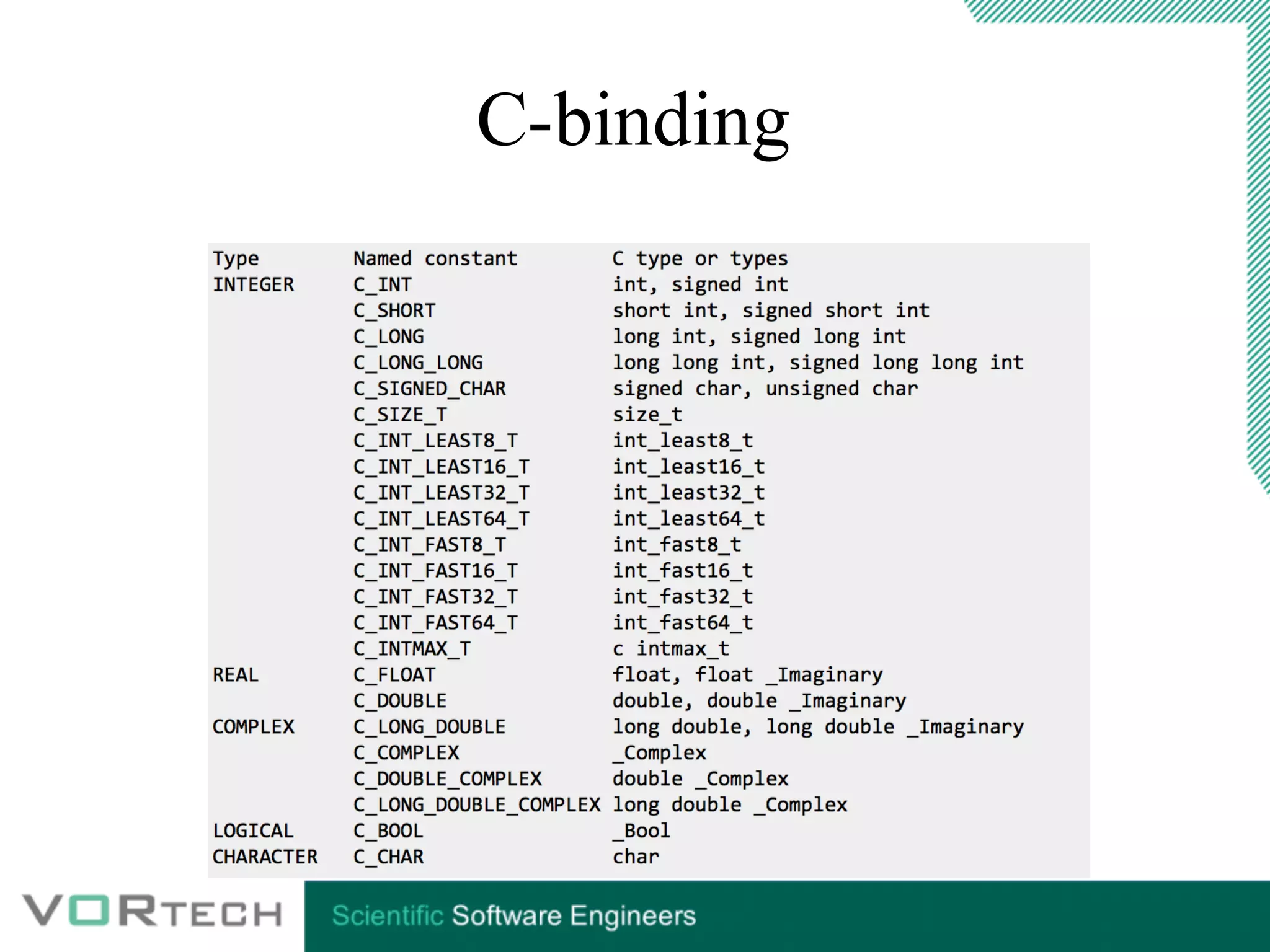

5) C-binding features which allow mixing Fortran and C code by controlling argument passing and data translation between the languages.

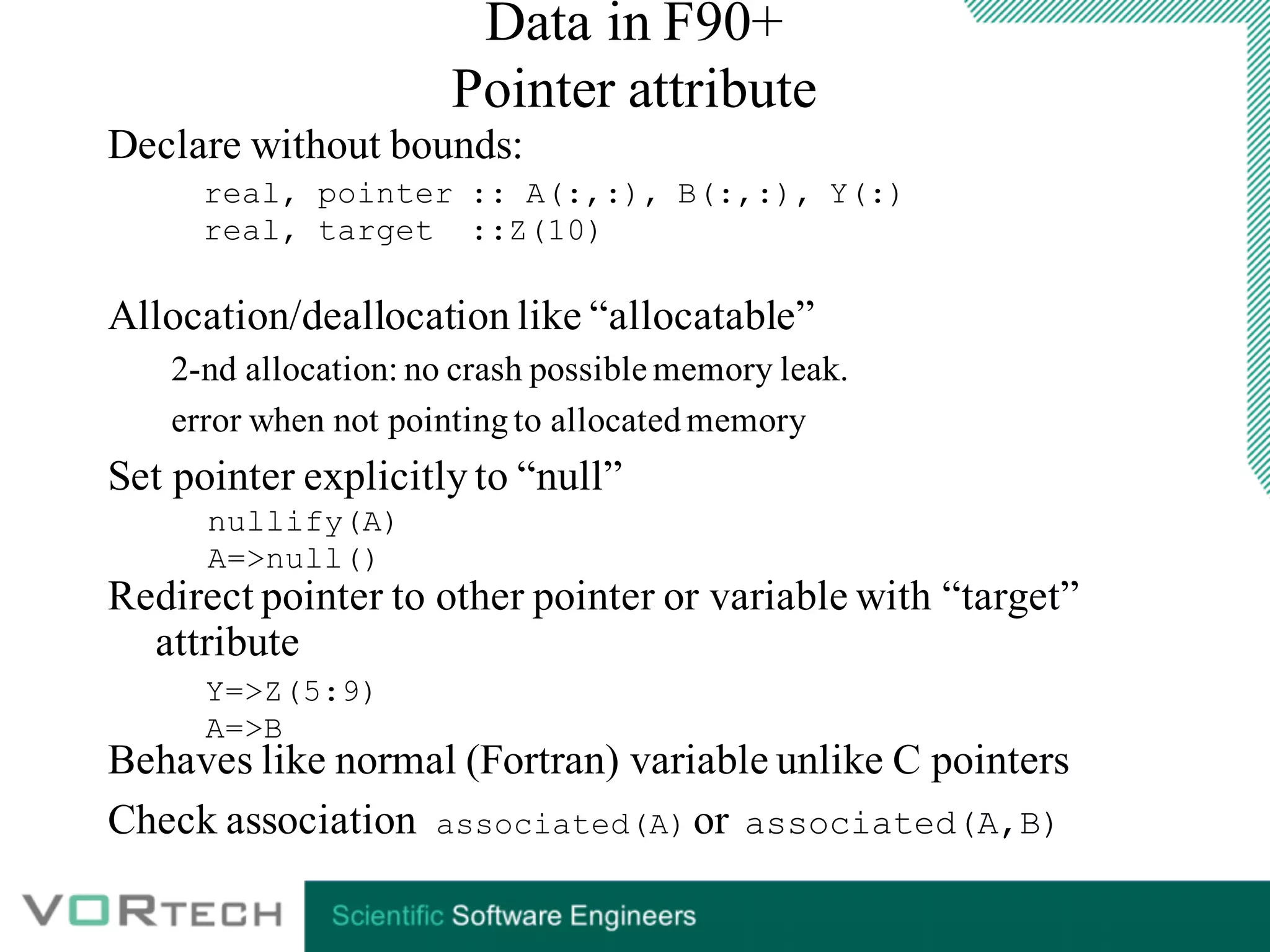

![Data in F90+

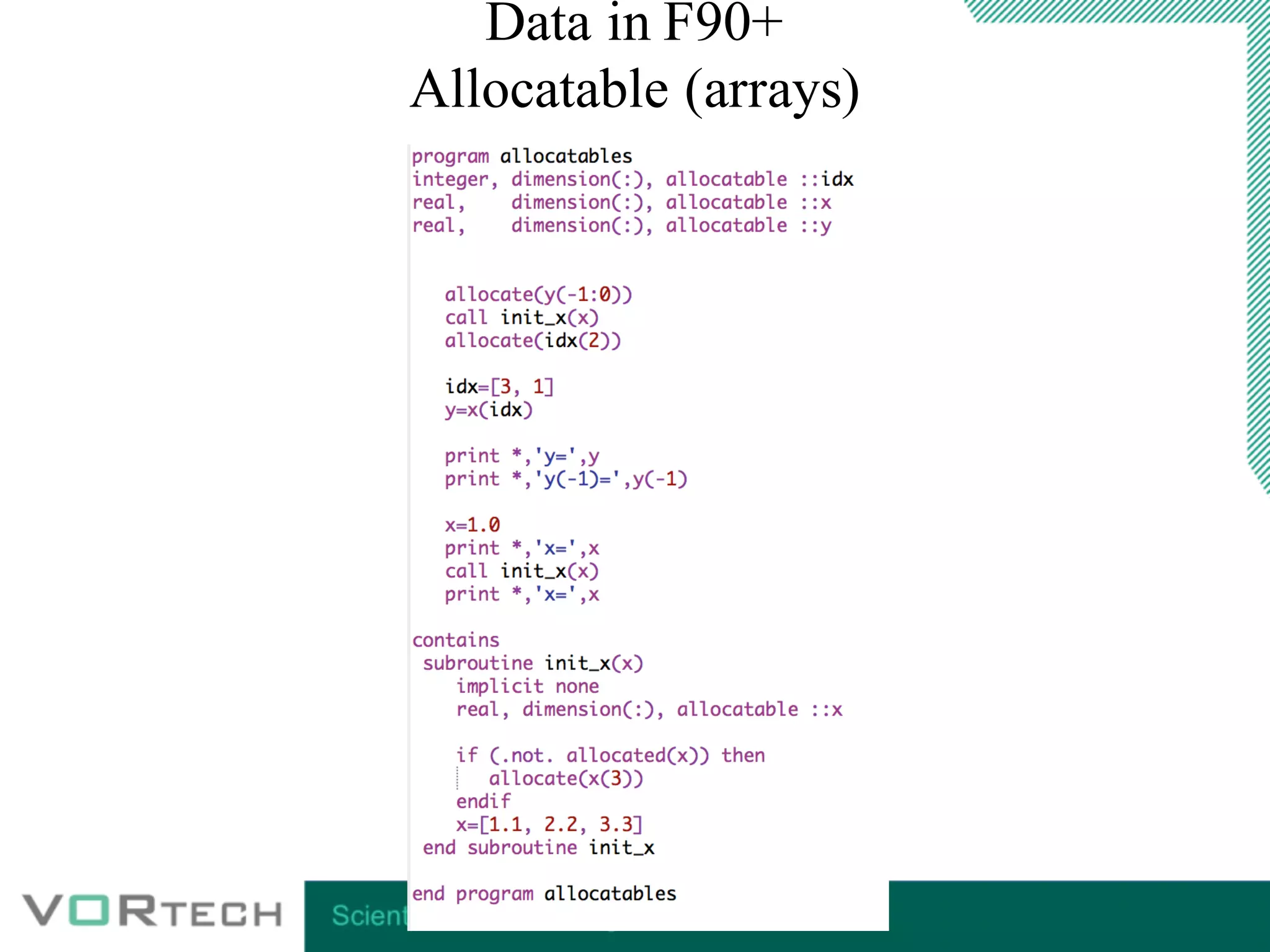

Allocatable (arrays)

Allocate wherever you want

Error when you allocate an allocated array

Automatic deallocation when out of scope

Note “save” attribute means never out of scope

Check allocation [de]allocate(<list>,stat=<variable>)

Allocation status: allocated or not allocated.

Declared in a module: autom. dealloc. platform dependent.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/87d9b180-a5c5-4a3c-9335-d2aac0d37741-160517120436/75/Introduction_modern_fortran_short-12-2048.jpg)

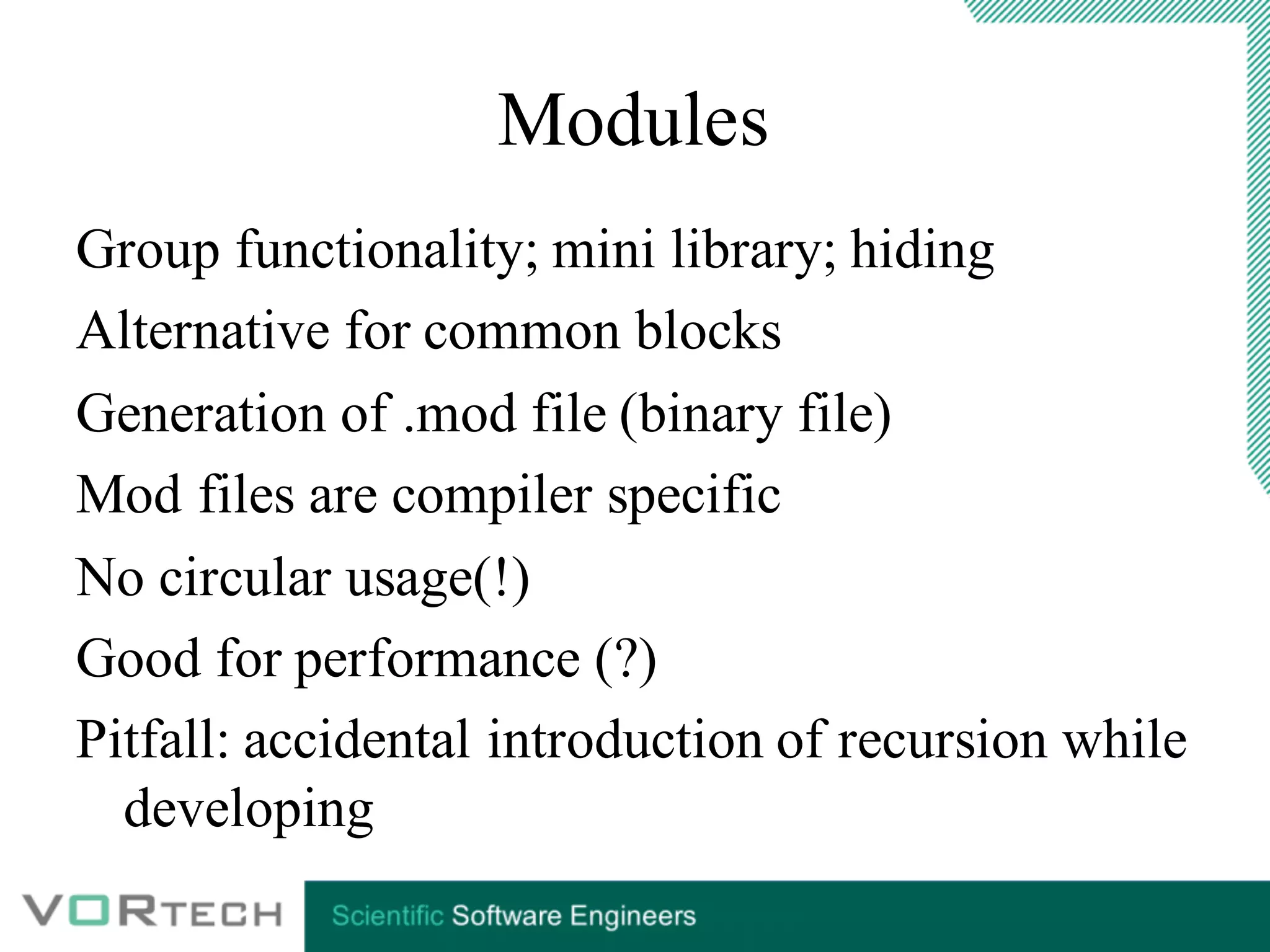

![Modules:

USE statementTwo forms:

use module-name [,name-as-used=>name-in-module]...

use module-name, only: [only-list]

only-list: names in module and rename clauses as above.

Compilation order: module before referencing program.

Example: program TPLMOD

use PLMOD

implicit none

integer :: IEOF

real :: XC, YC

call PLINI

do

read(*,*,iostat=IEOF) XC, YC

if( IEOF /= 0) exit

call PLADD( XC, YC)

end do

call PLWRI( 6)

end program TPLMOD](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/87d9b180-a5c5-4a3c-9335-d2aac0d37741-160517120436/75/Introduction_modern_fortran_short-17-2048.jpg)