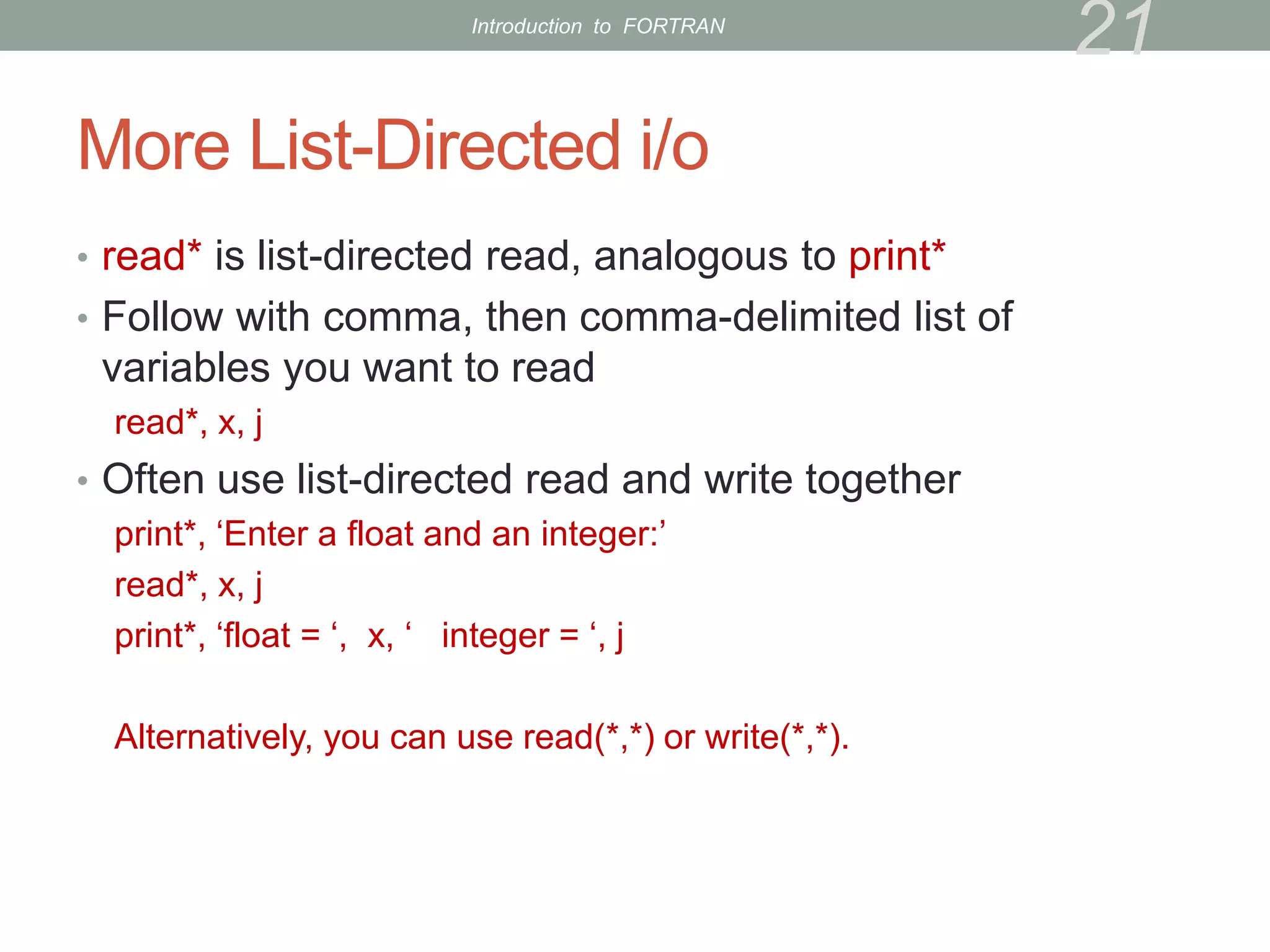

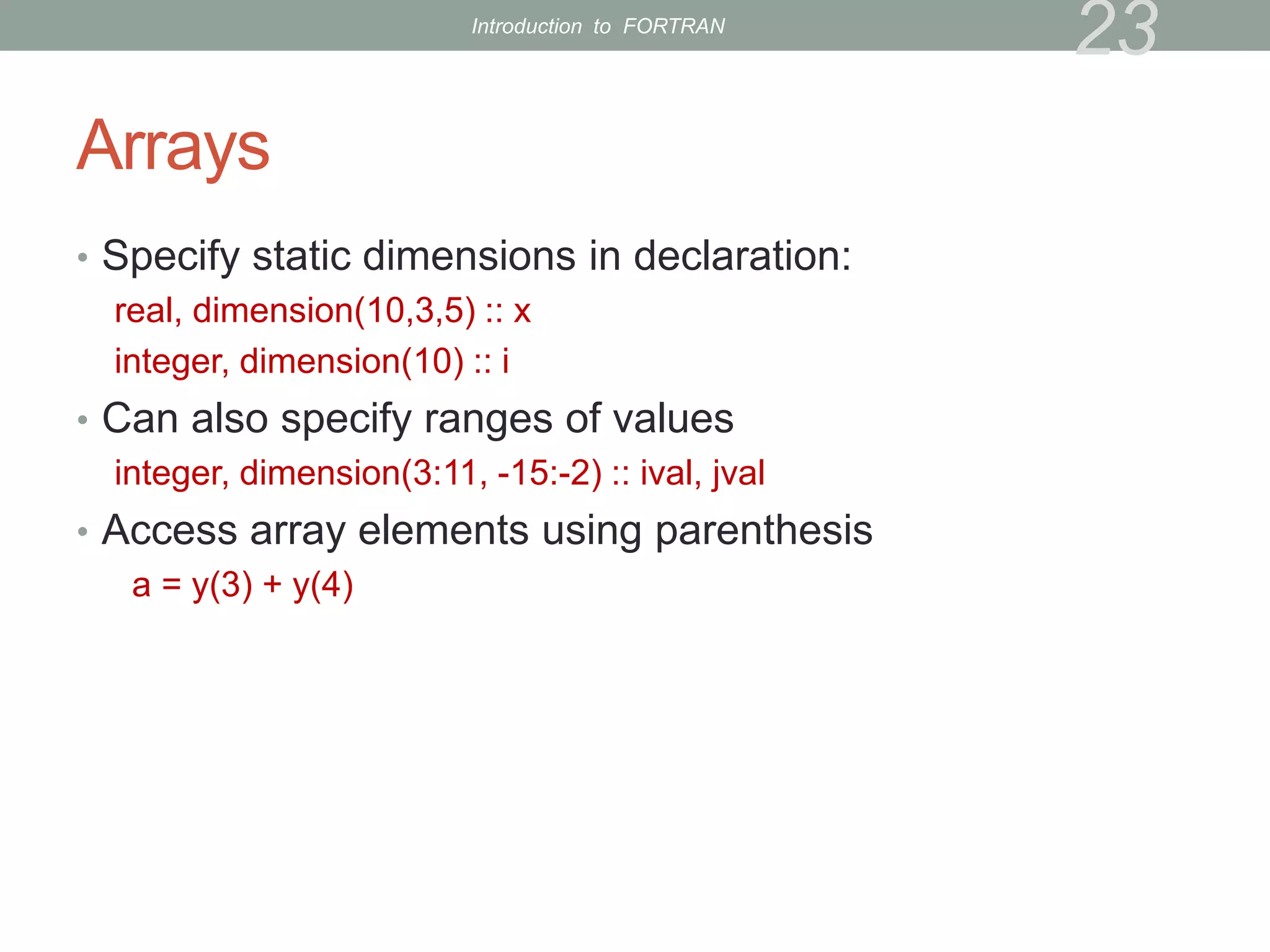

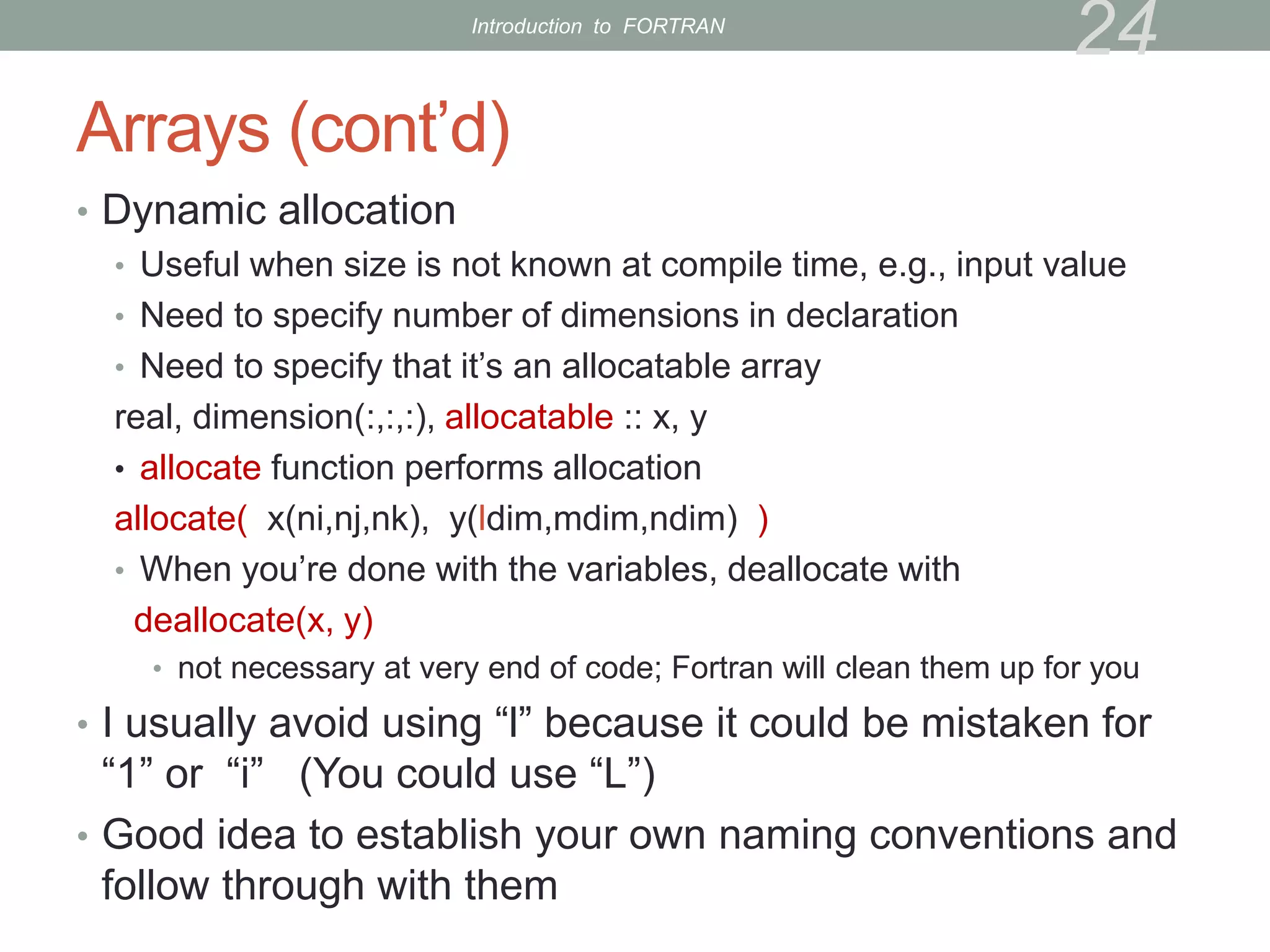

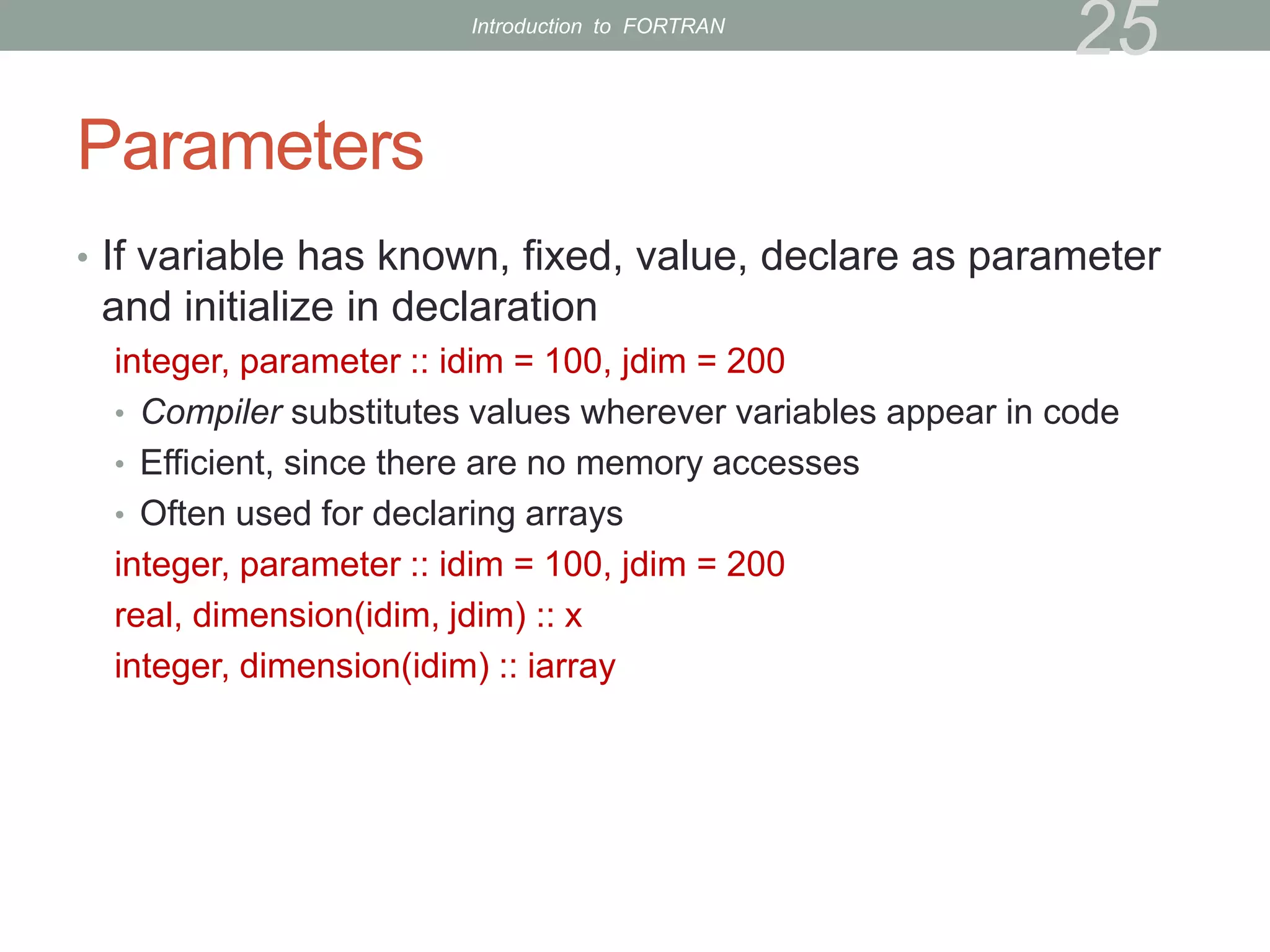

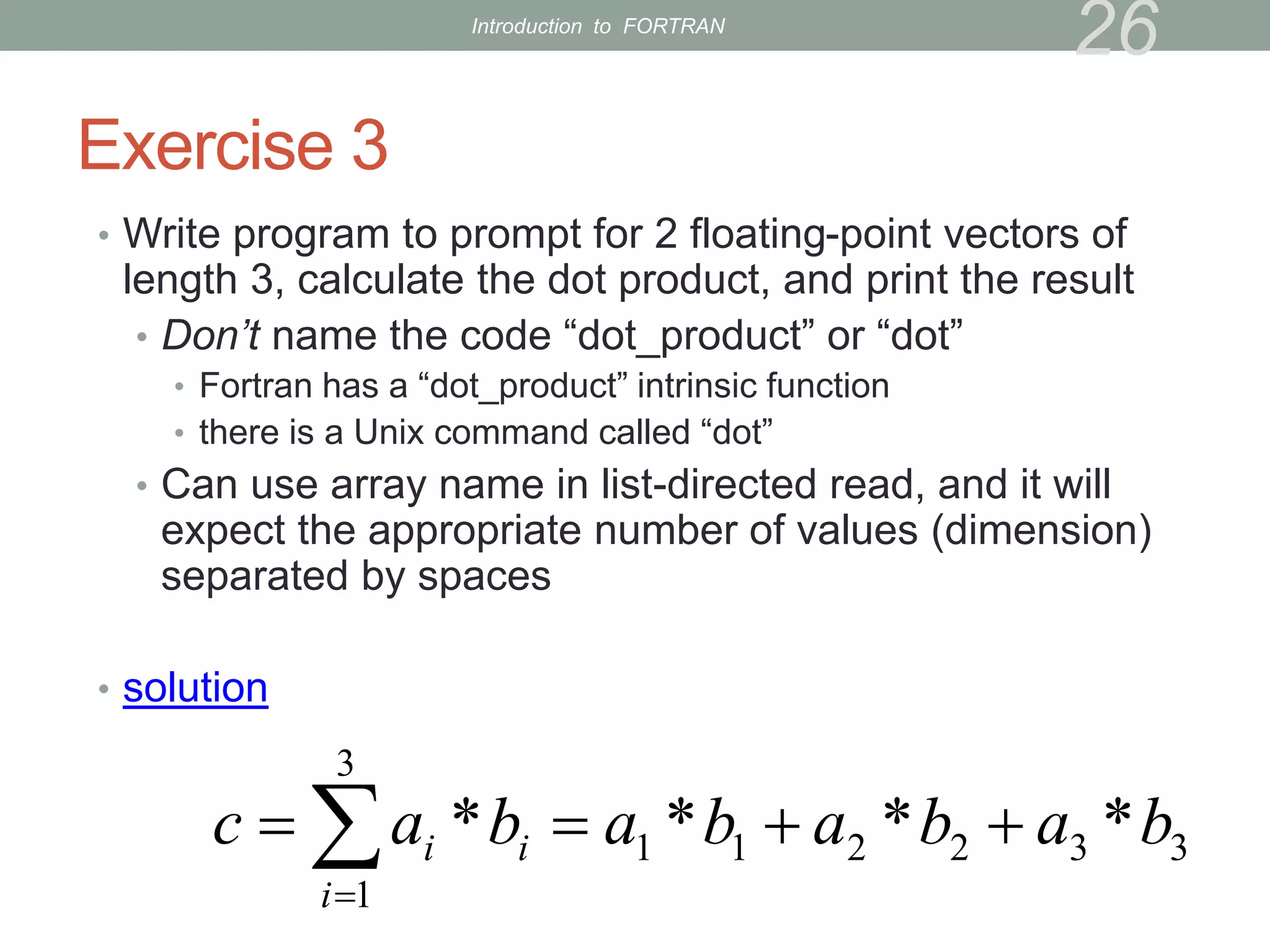

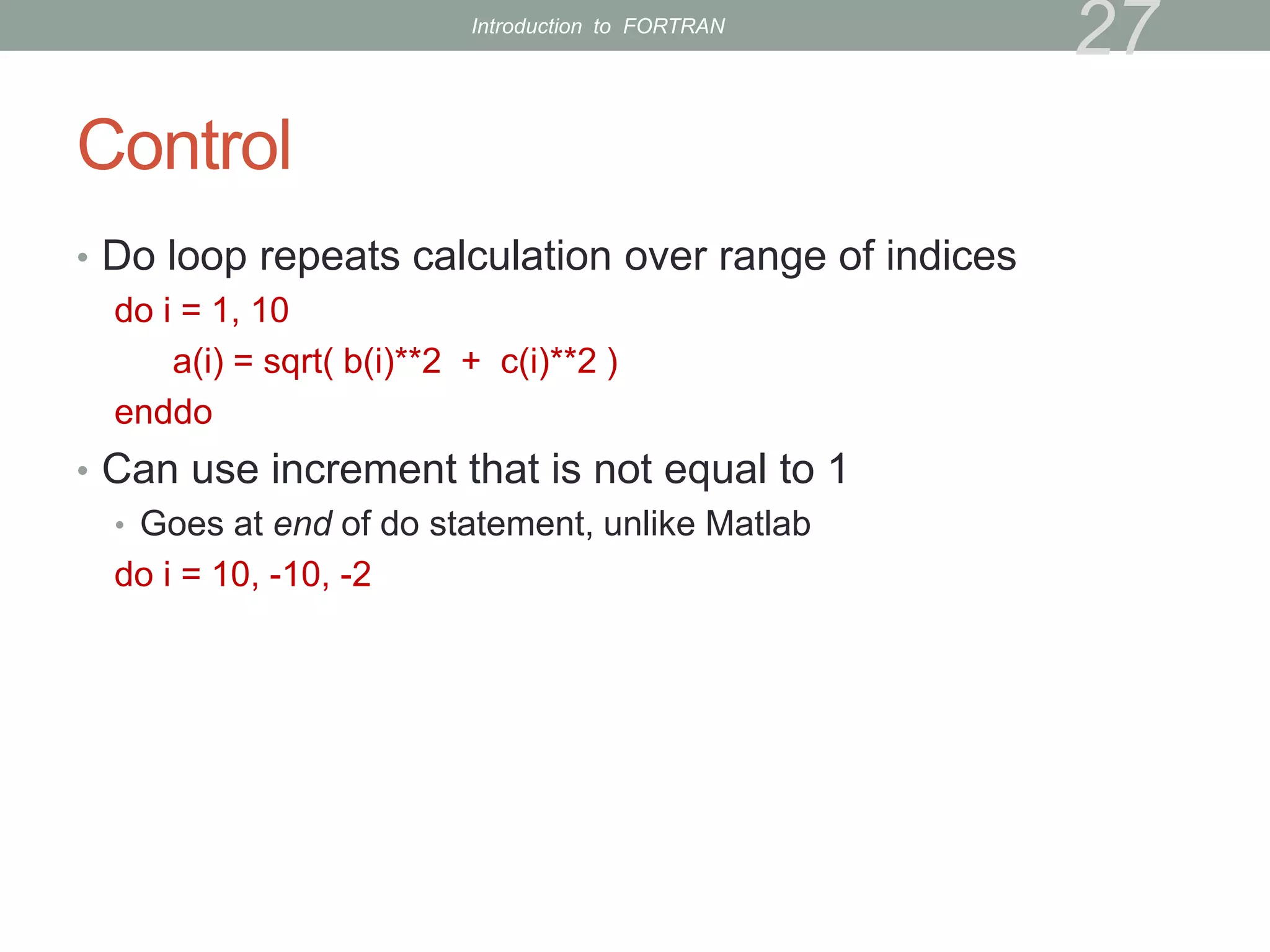

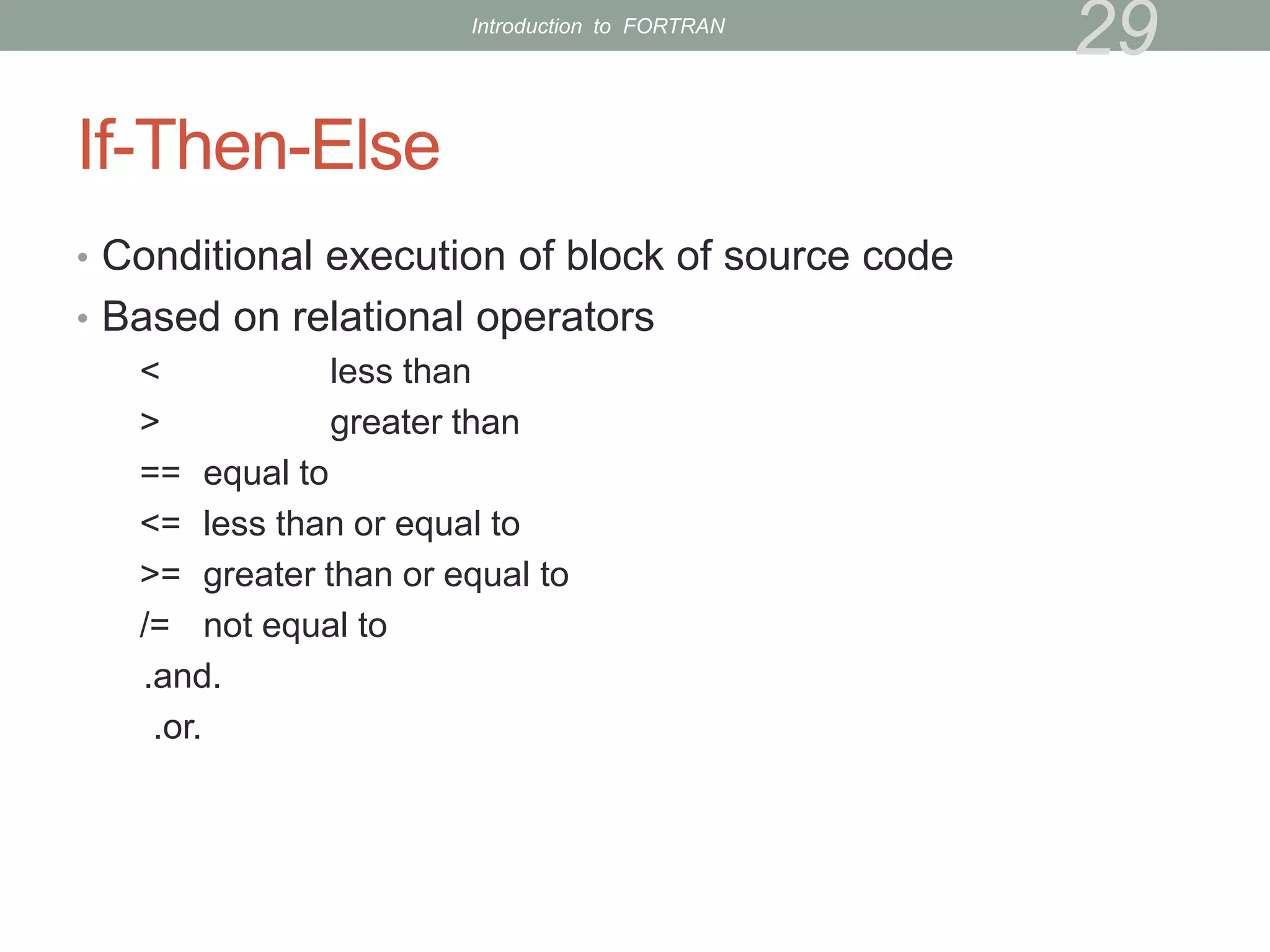

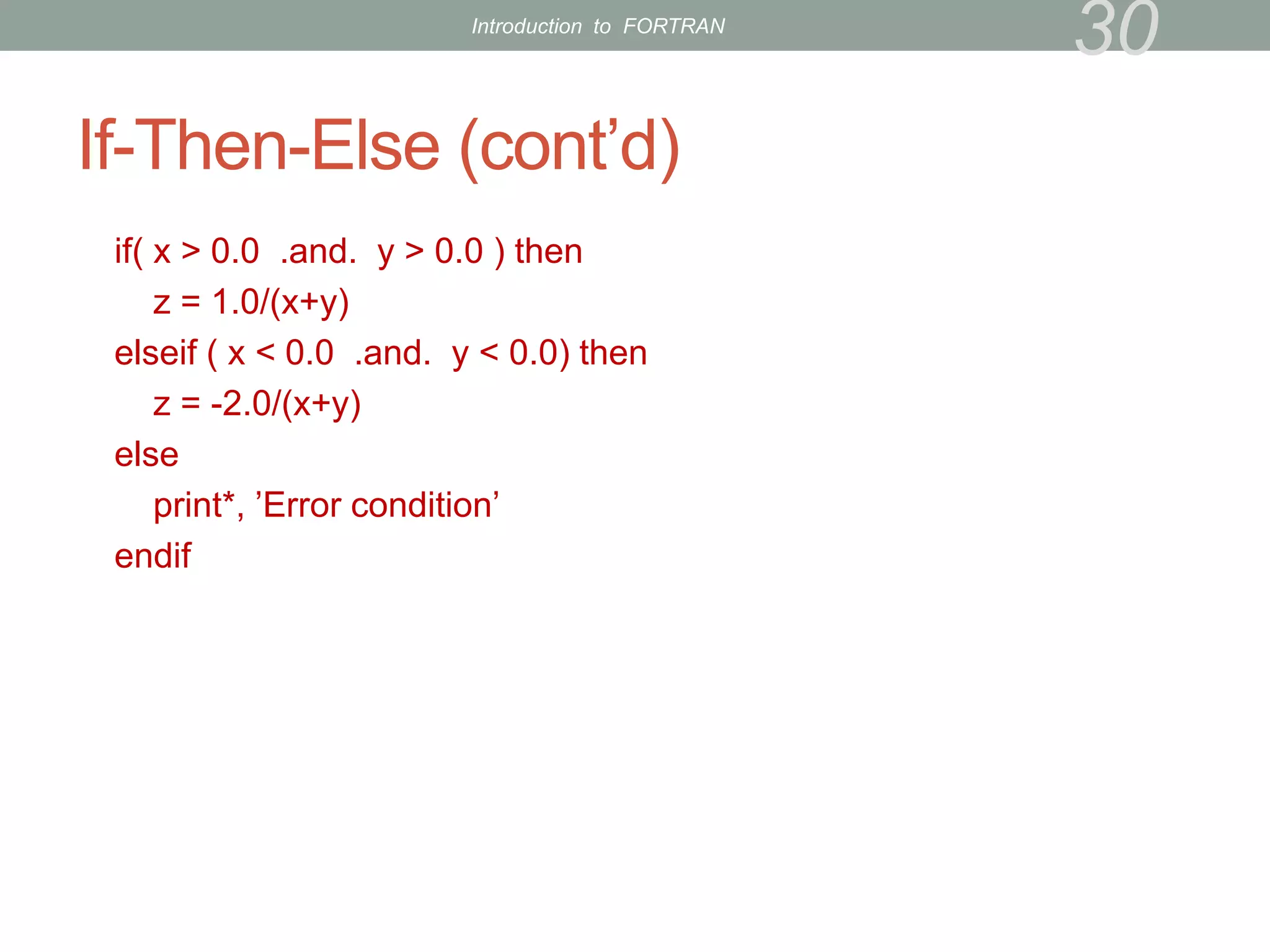

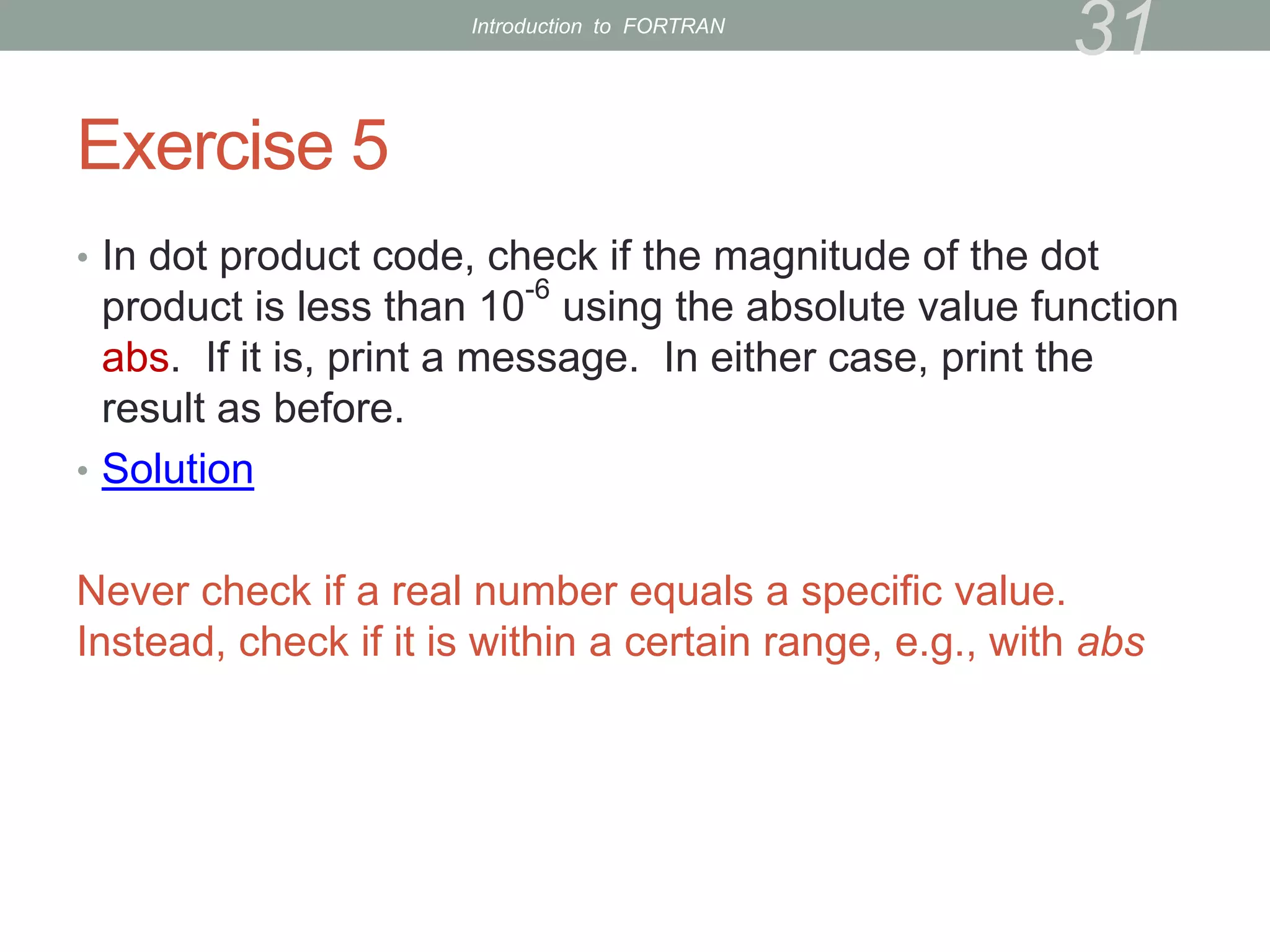

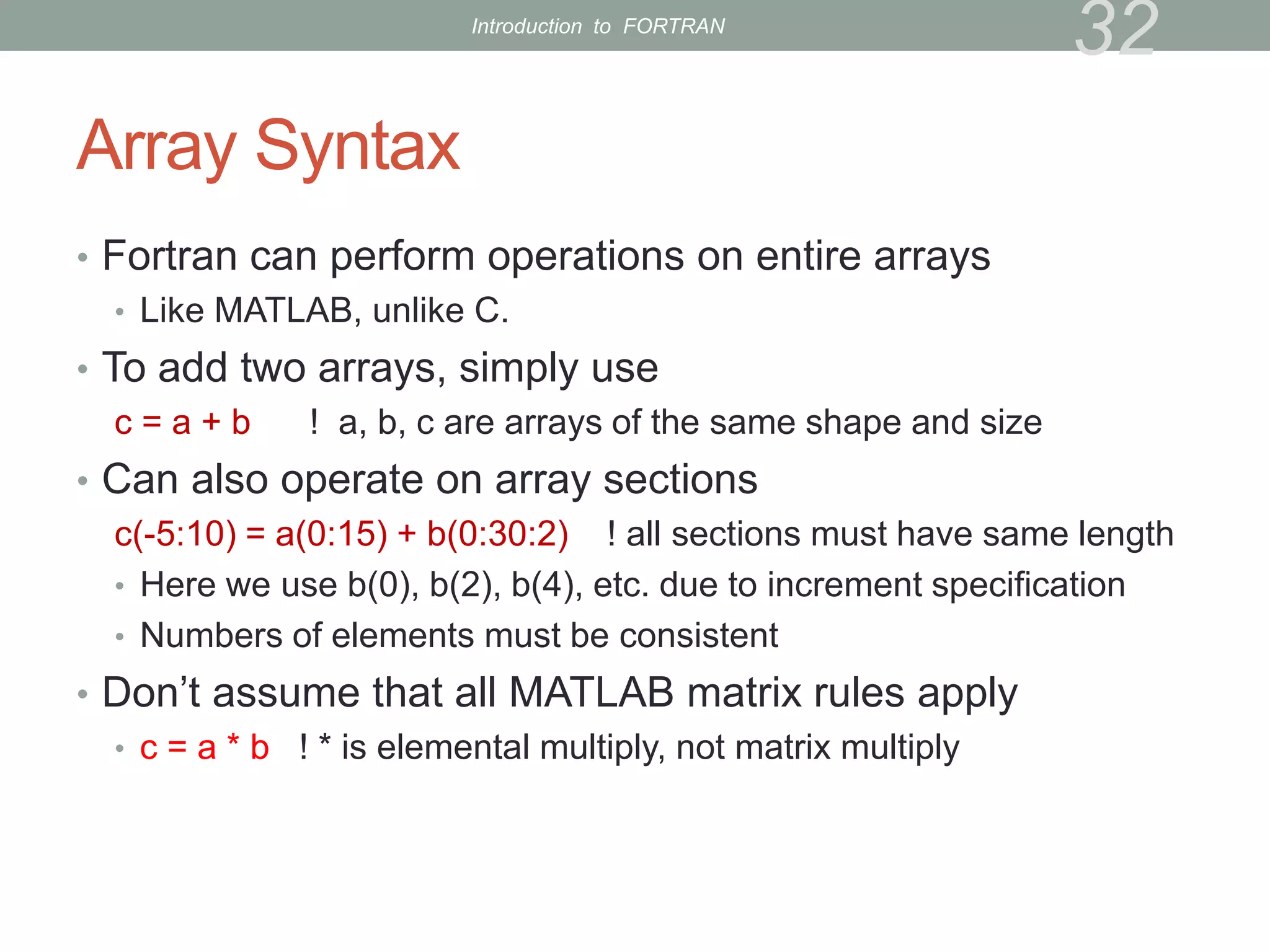

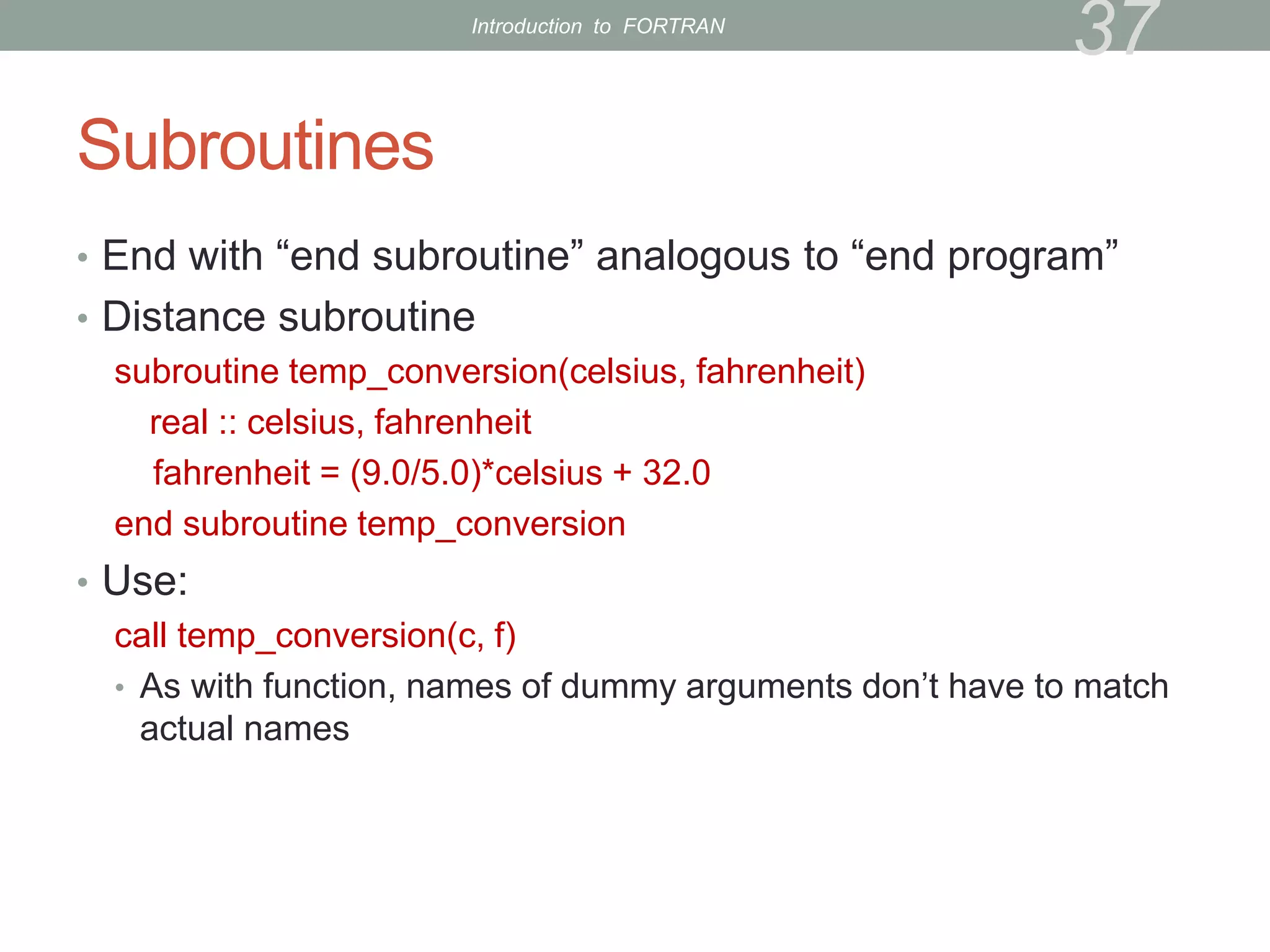

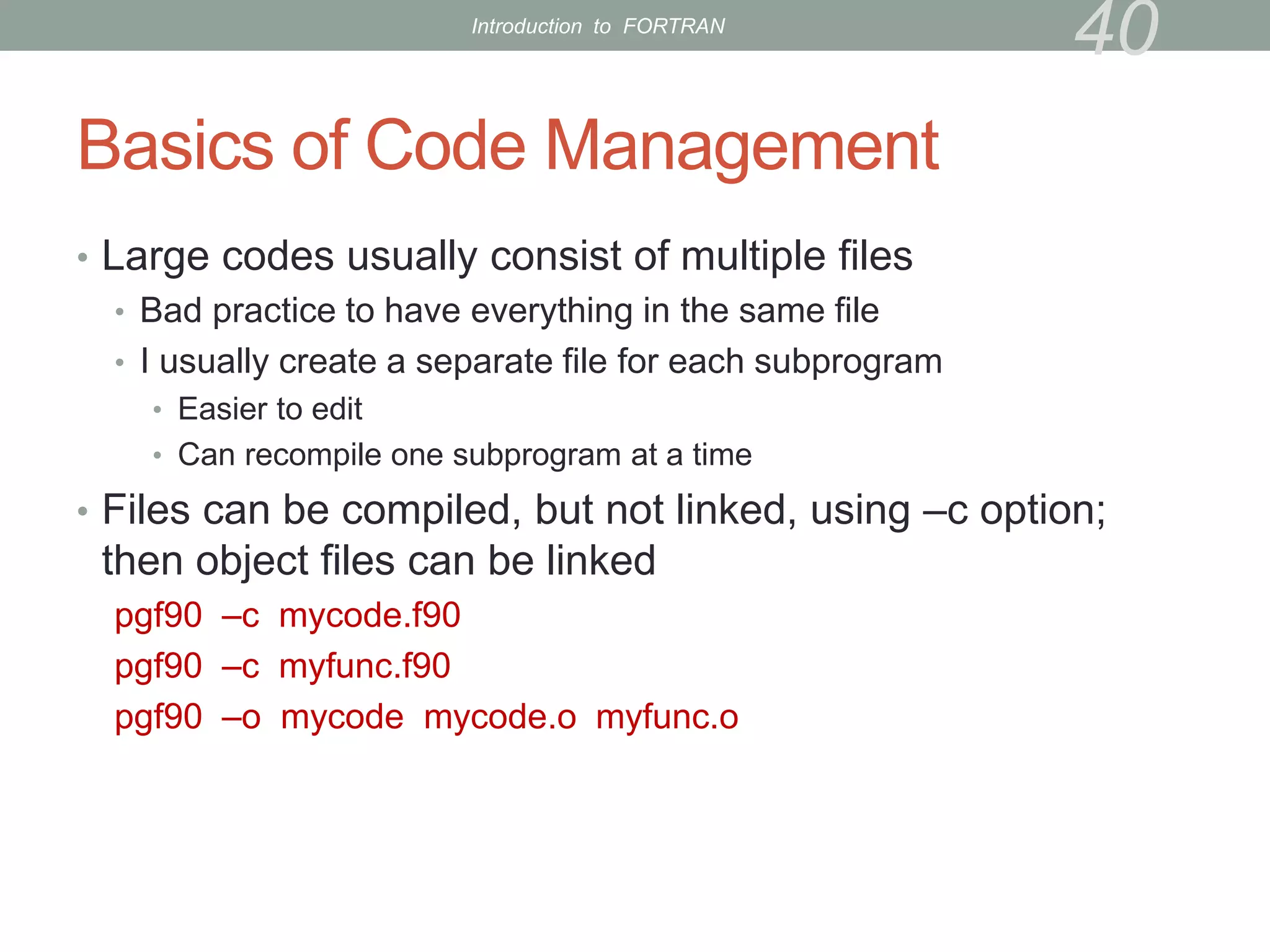

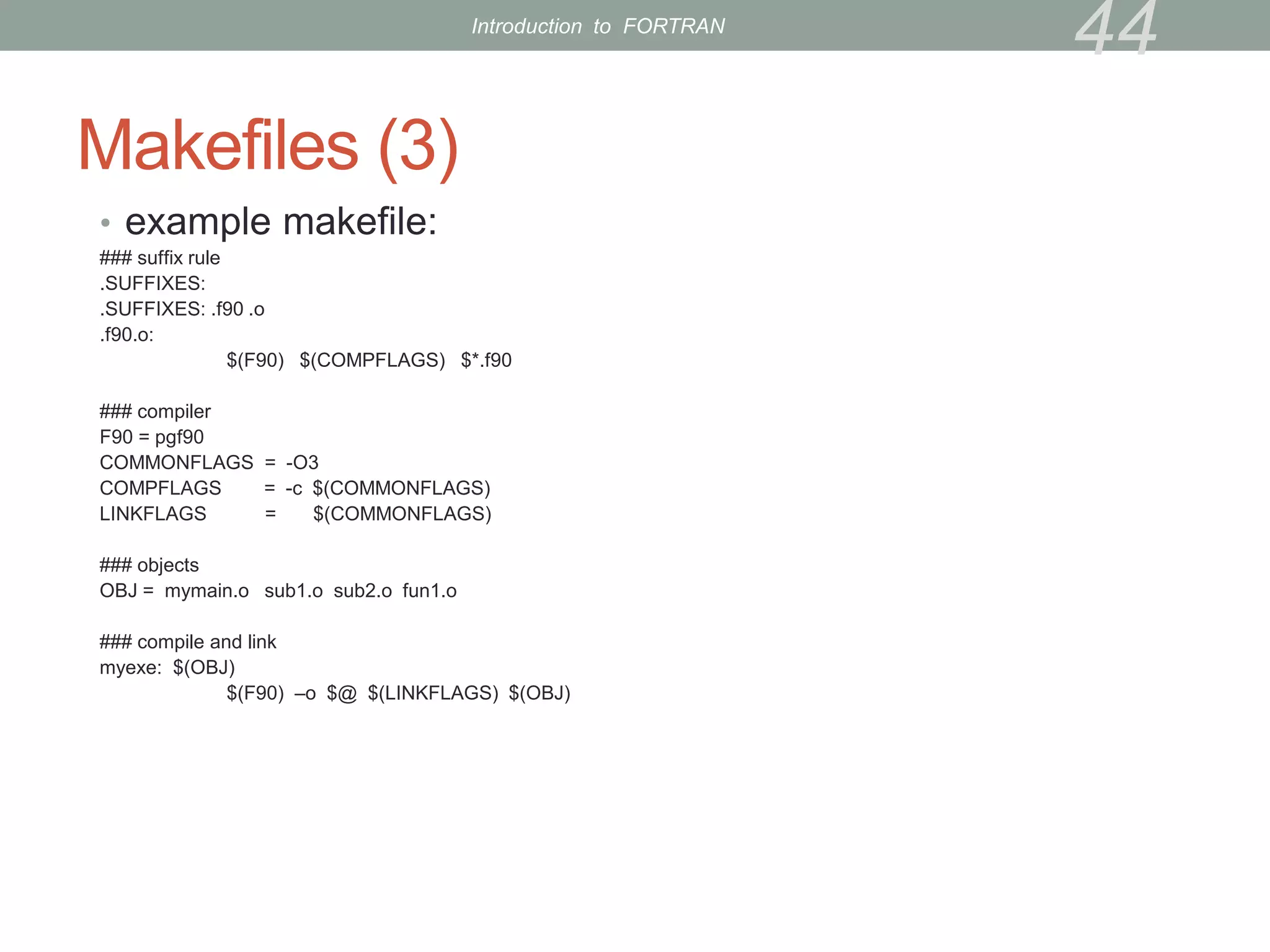

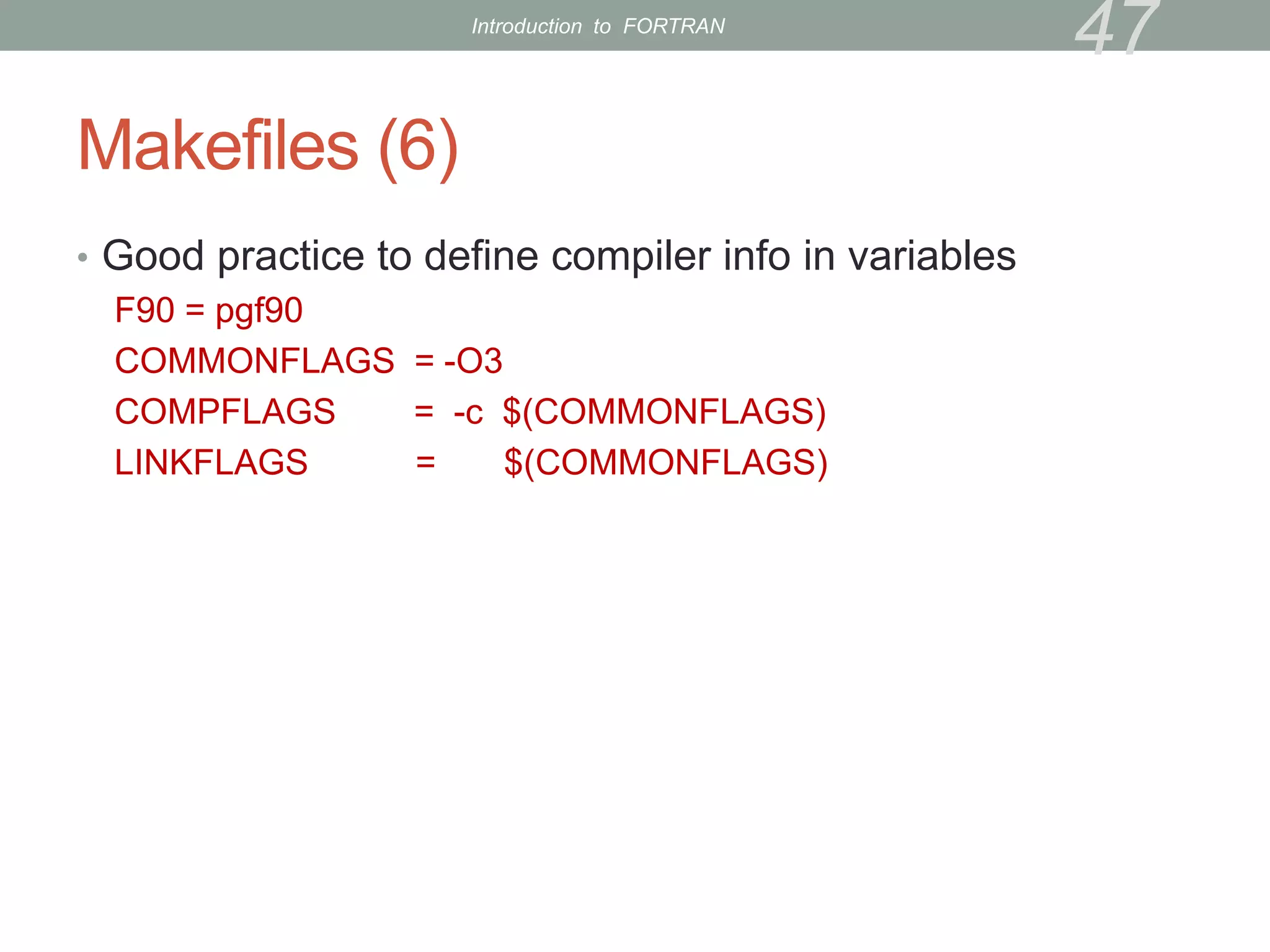

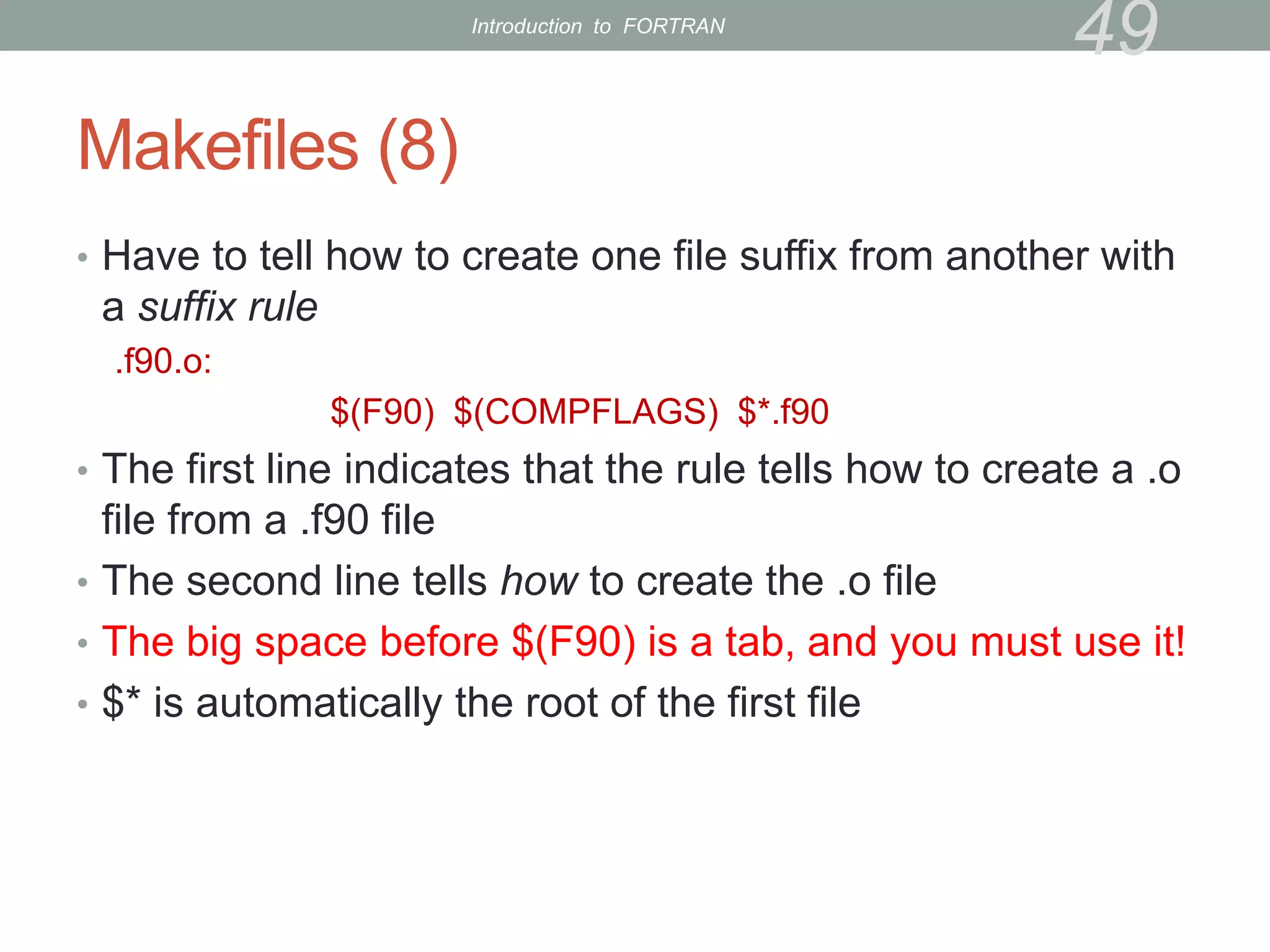

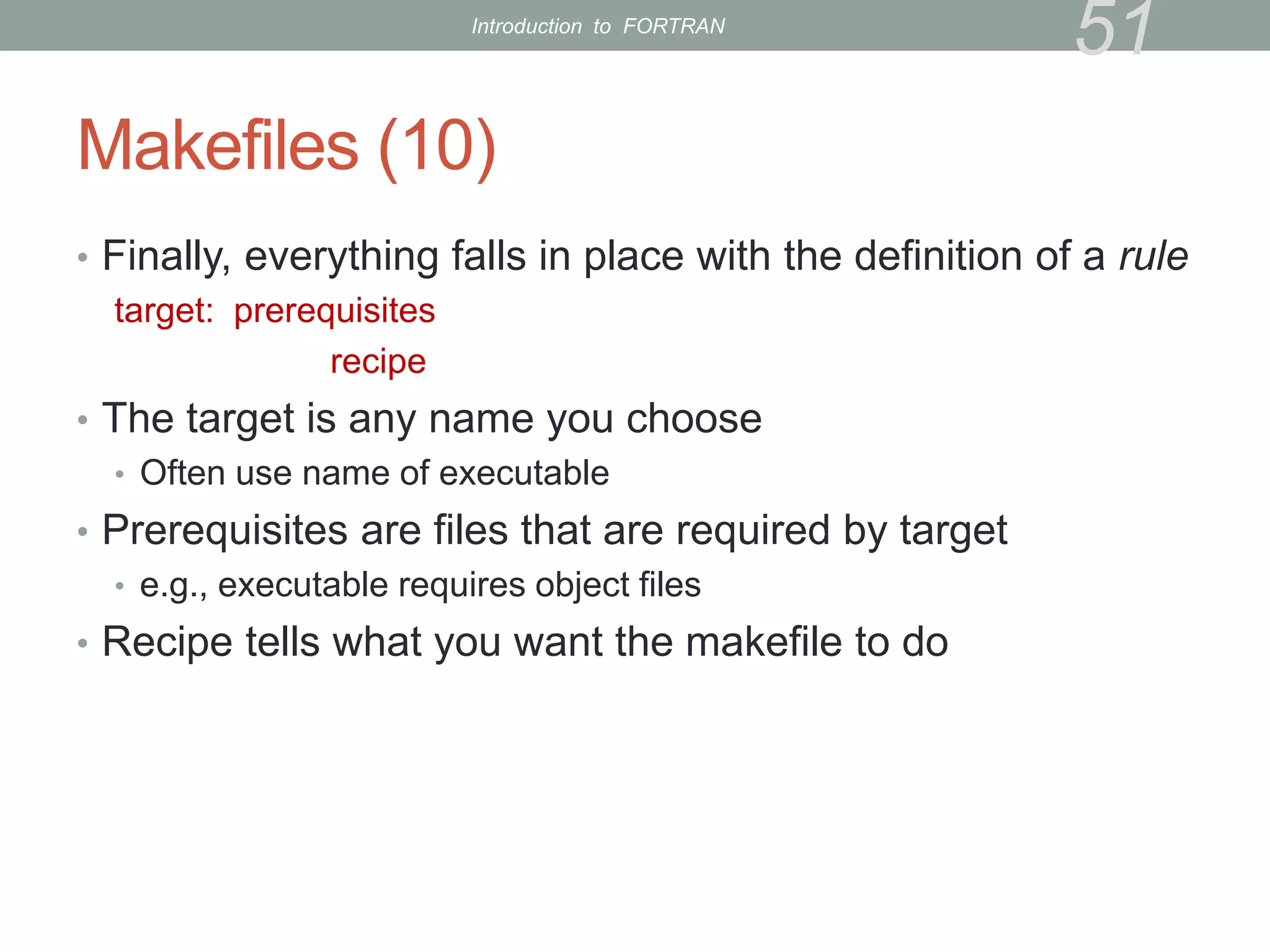

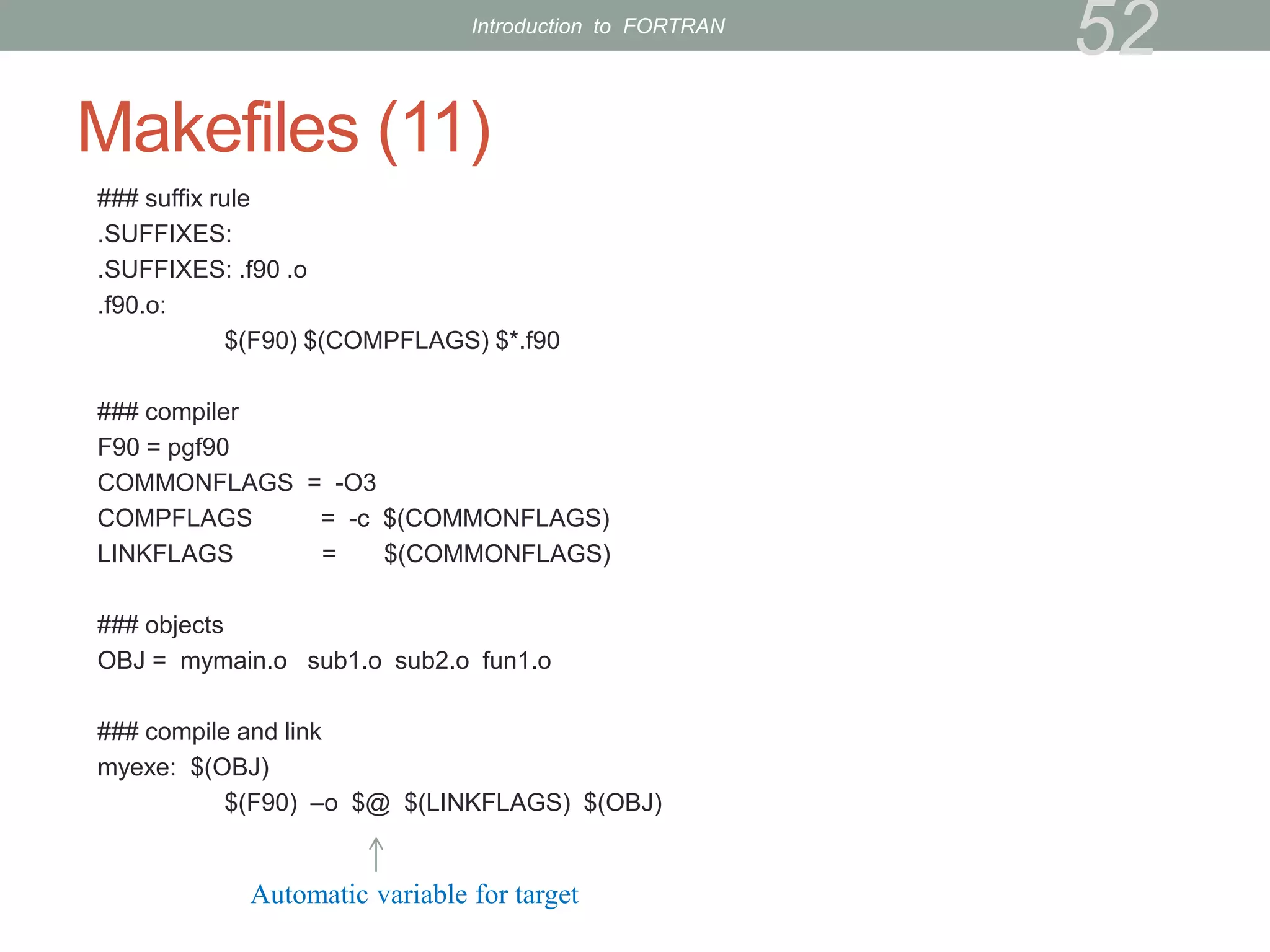

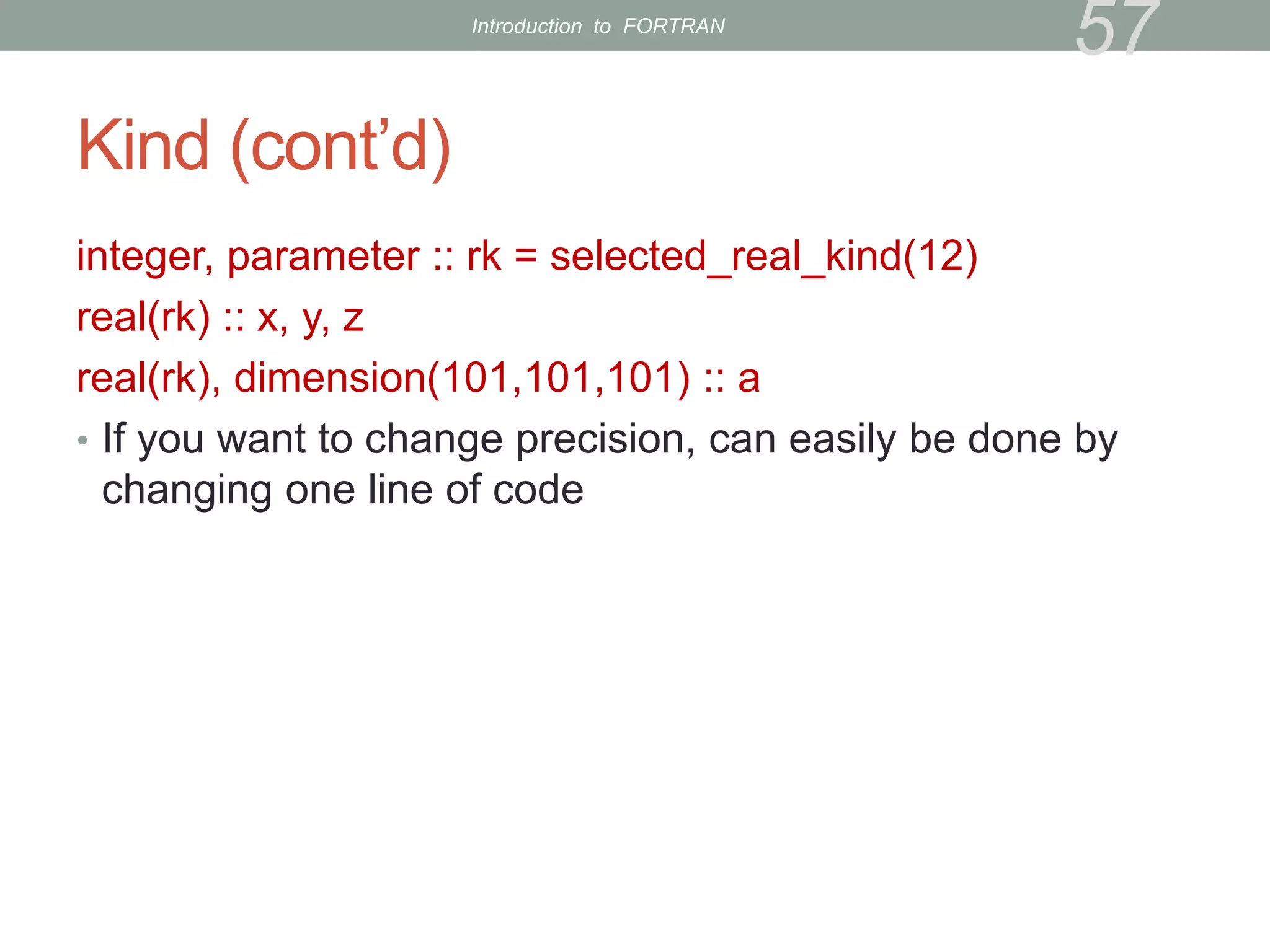

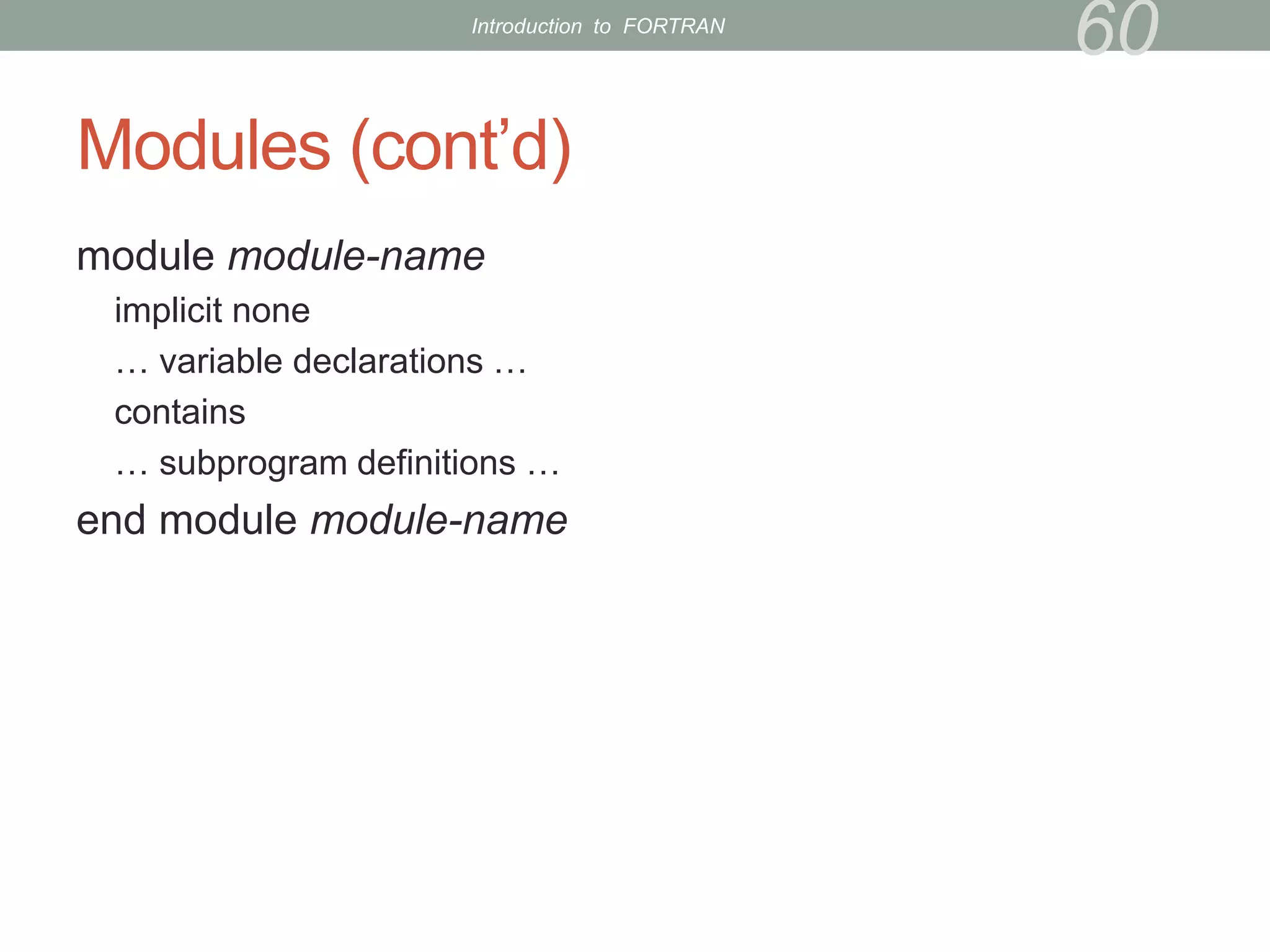

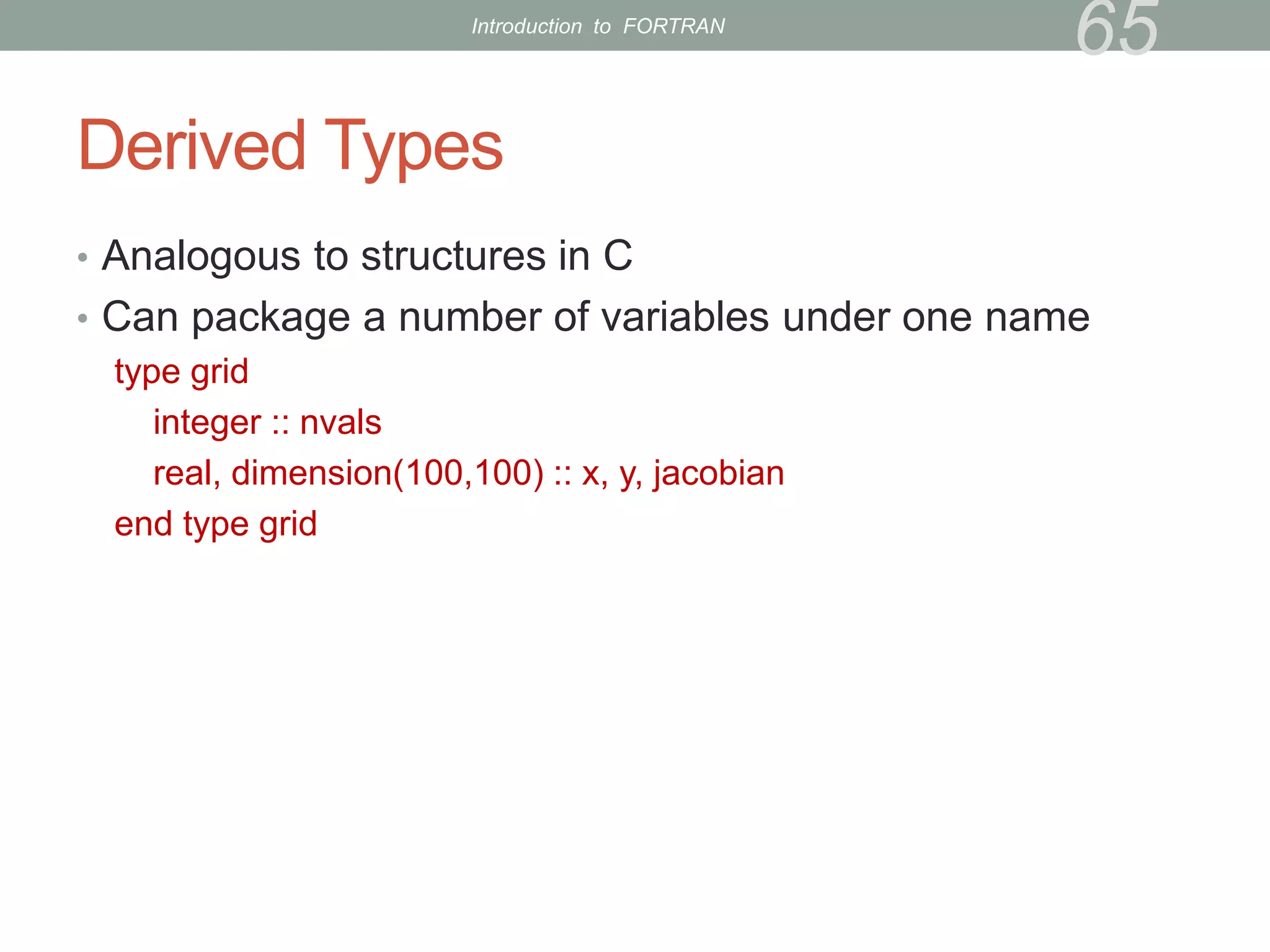

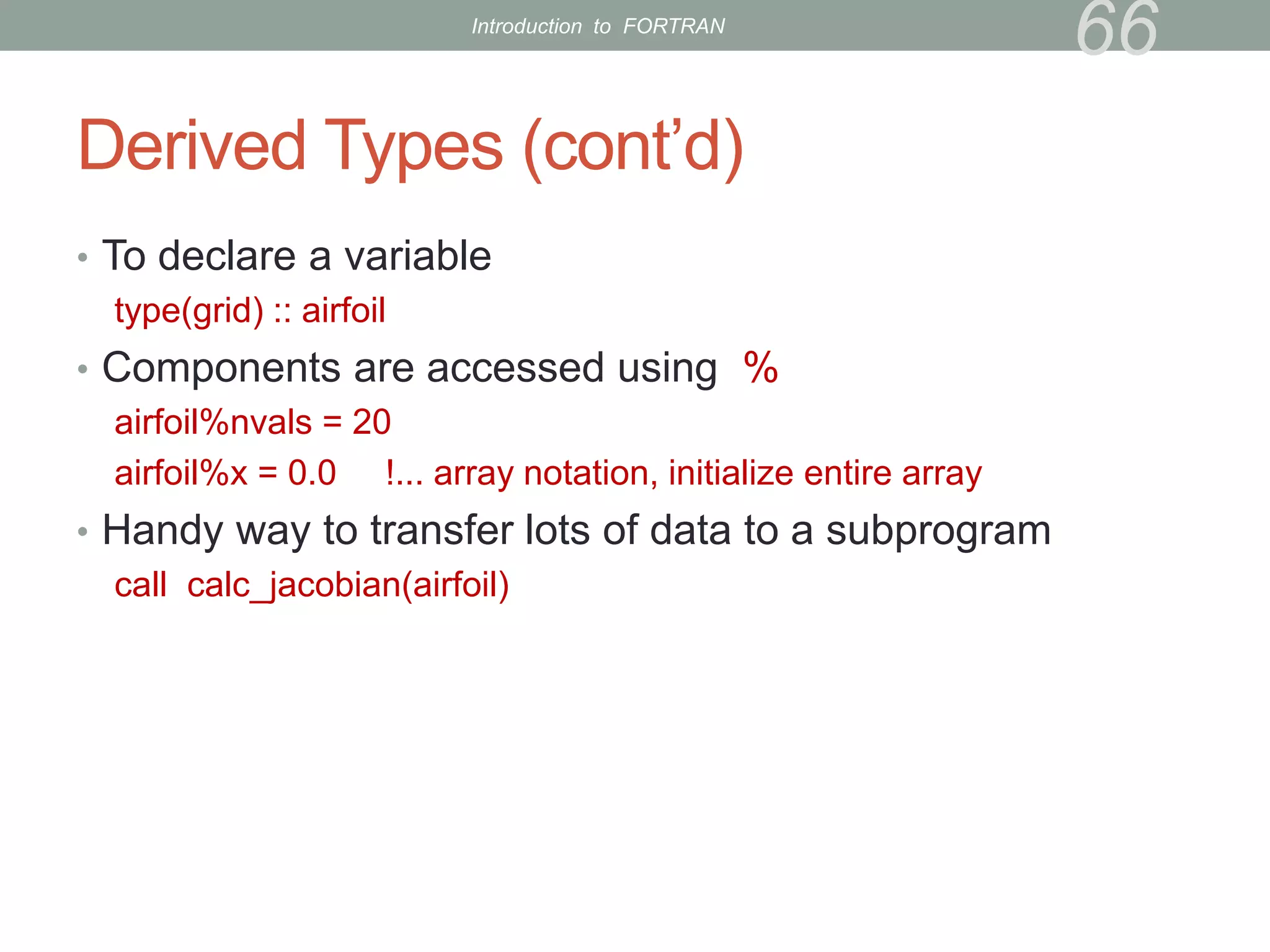

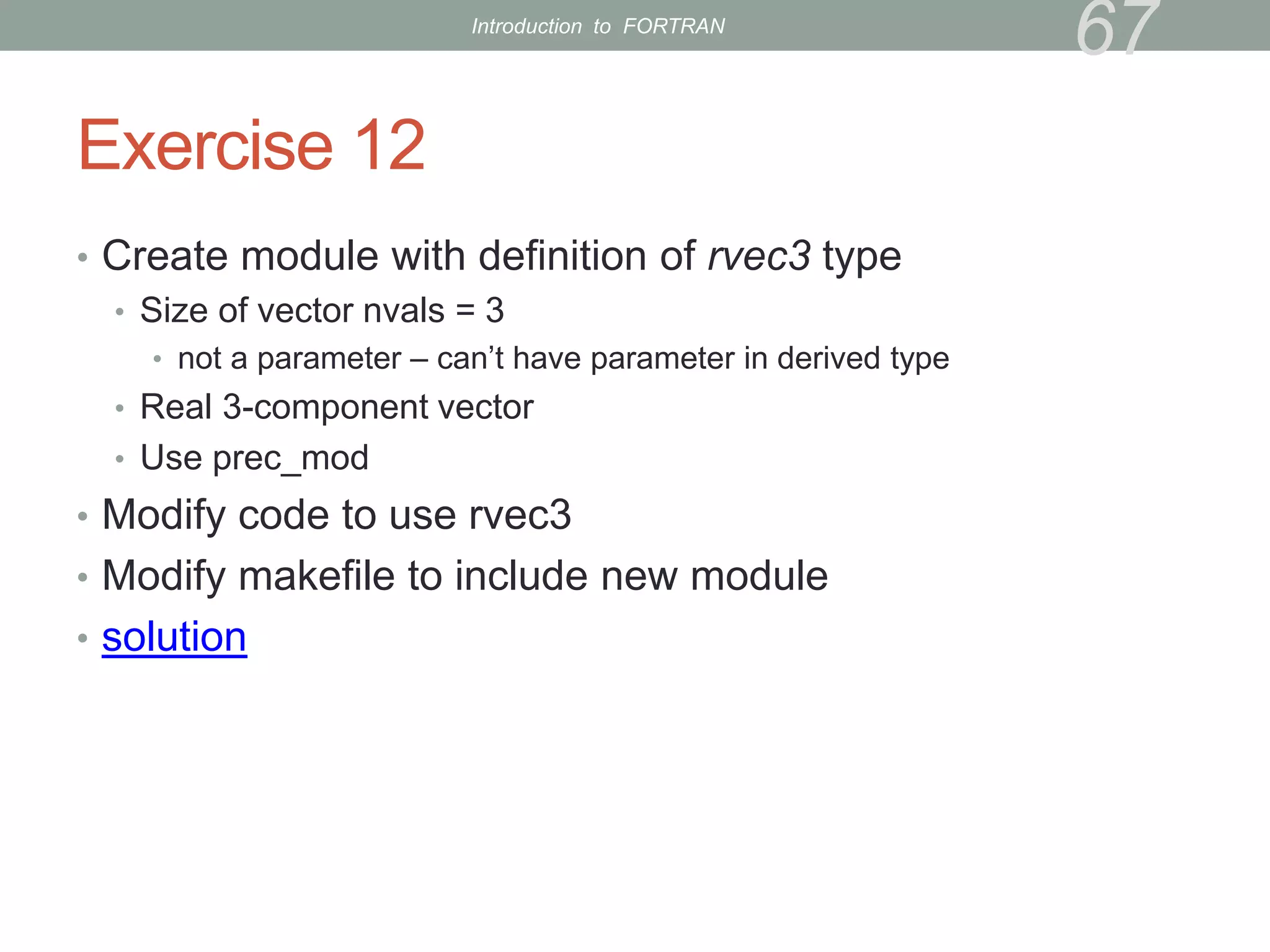

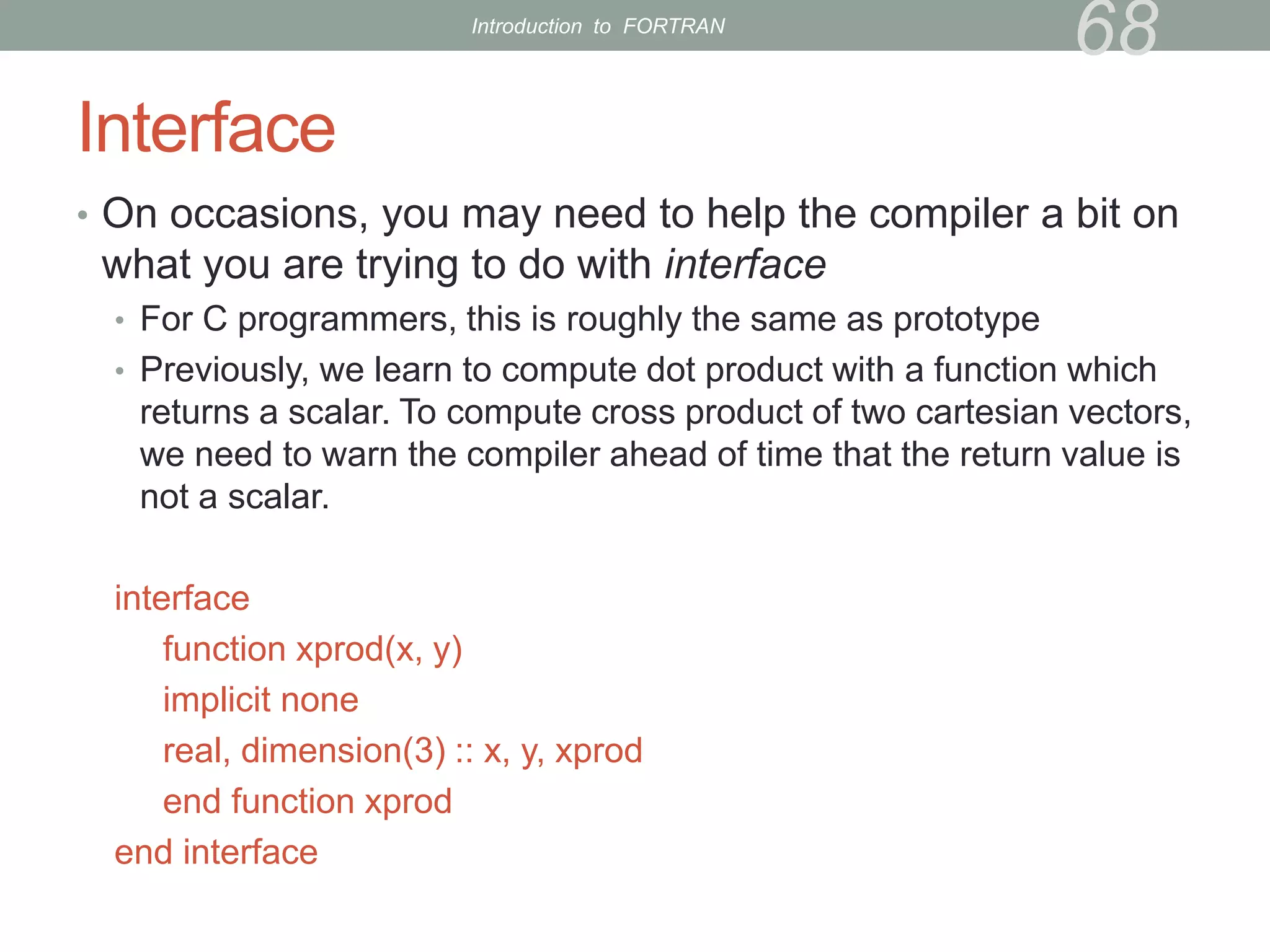

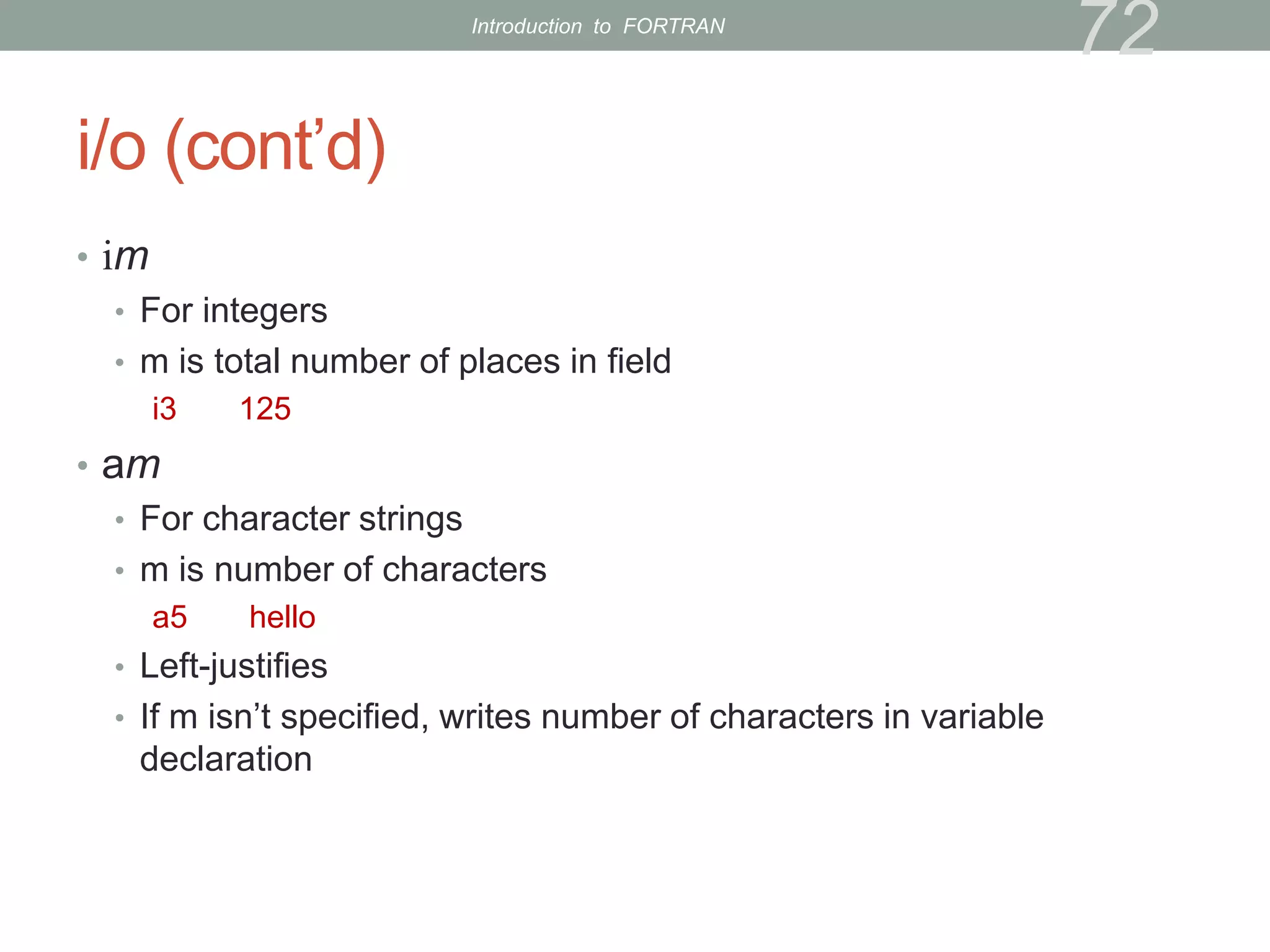

This document provides an introduction to the Fortran programming language. It outlines the history of Fortran, beginning in 1957 as the first widely used high-level computer language. It describes the basic syntax of Fortran, including variables, types, arithmetic, arrays, control structures, and subprograms. The document also discusses compiling Fortran code and managing projects with makefiles. Exercises are provided to help learn the fundamentals of writing Fortran programs.