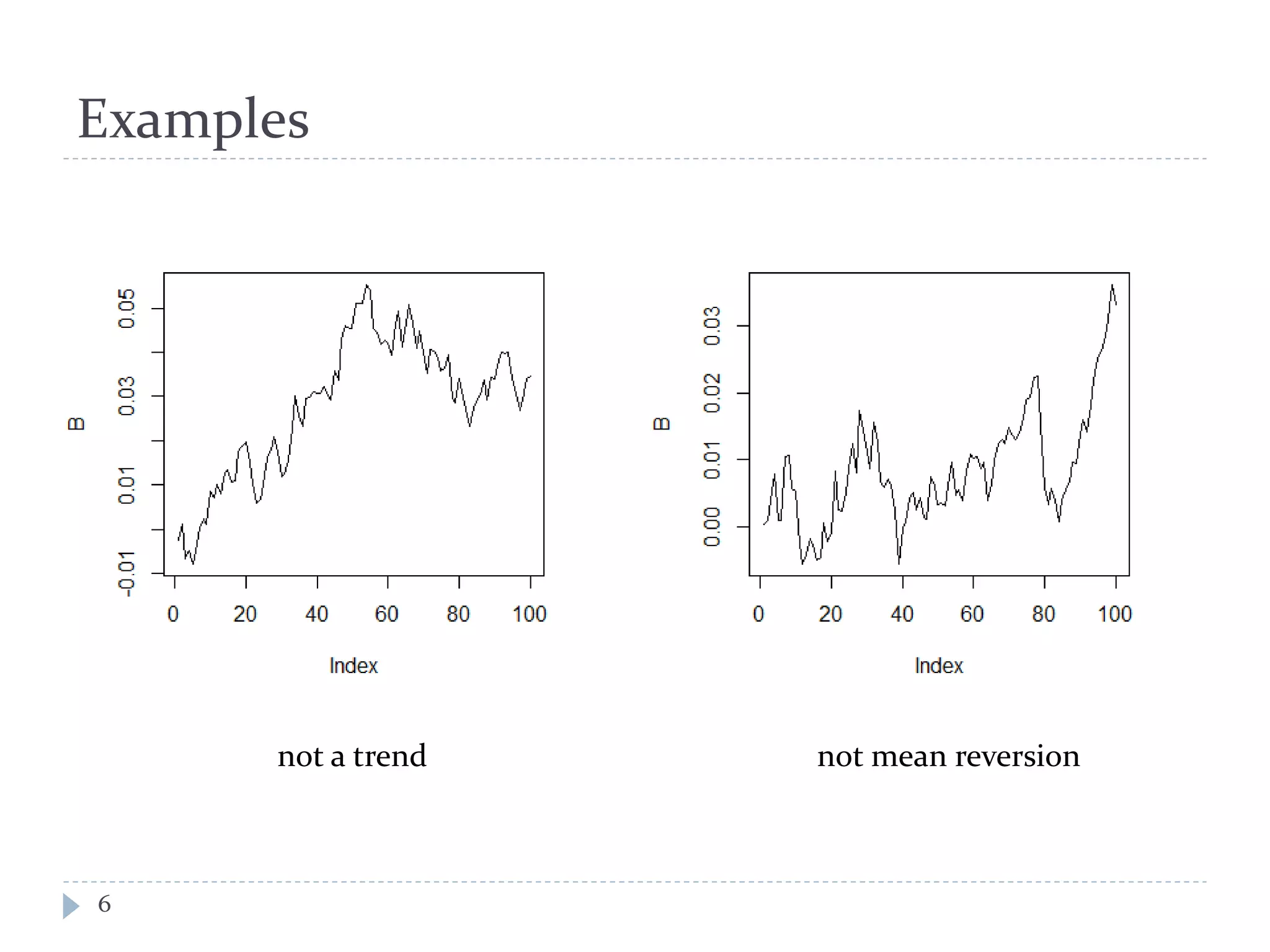

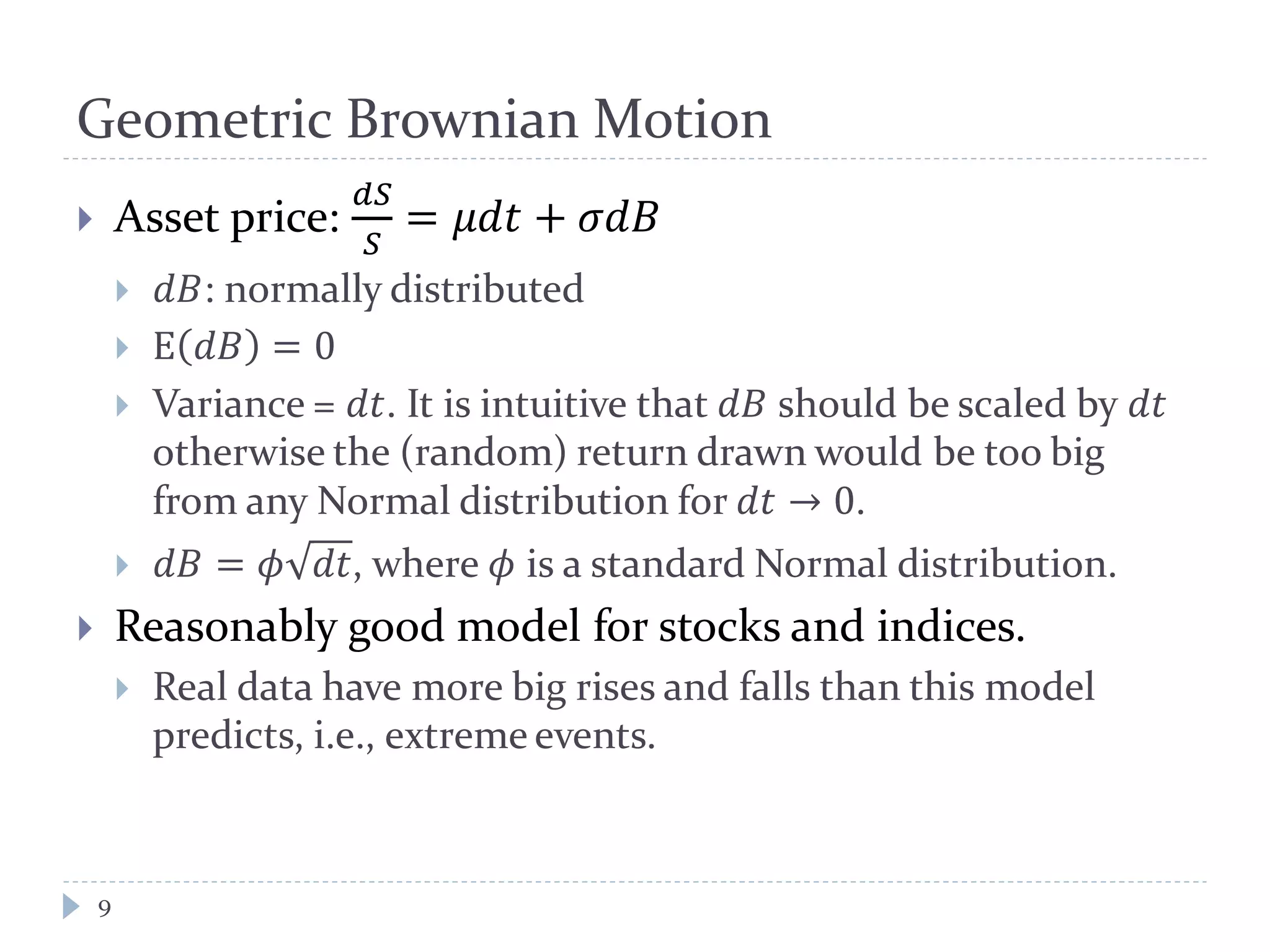

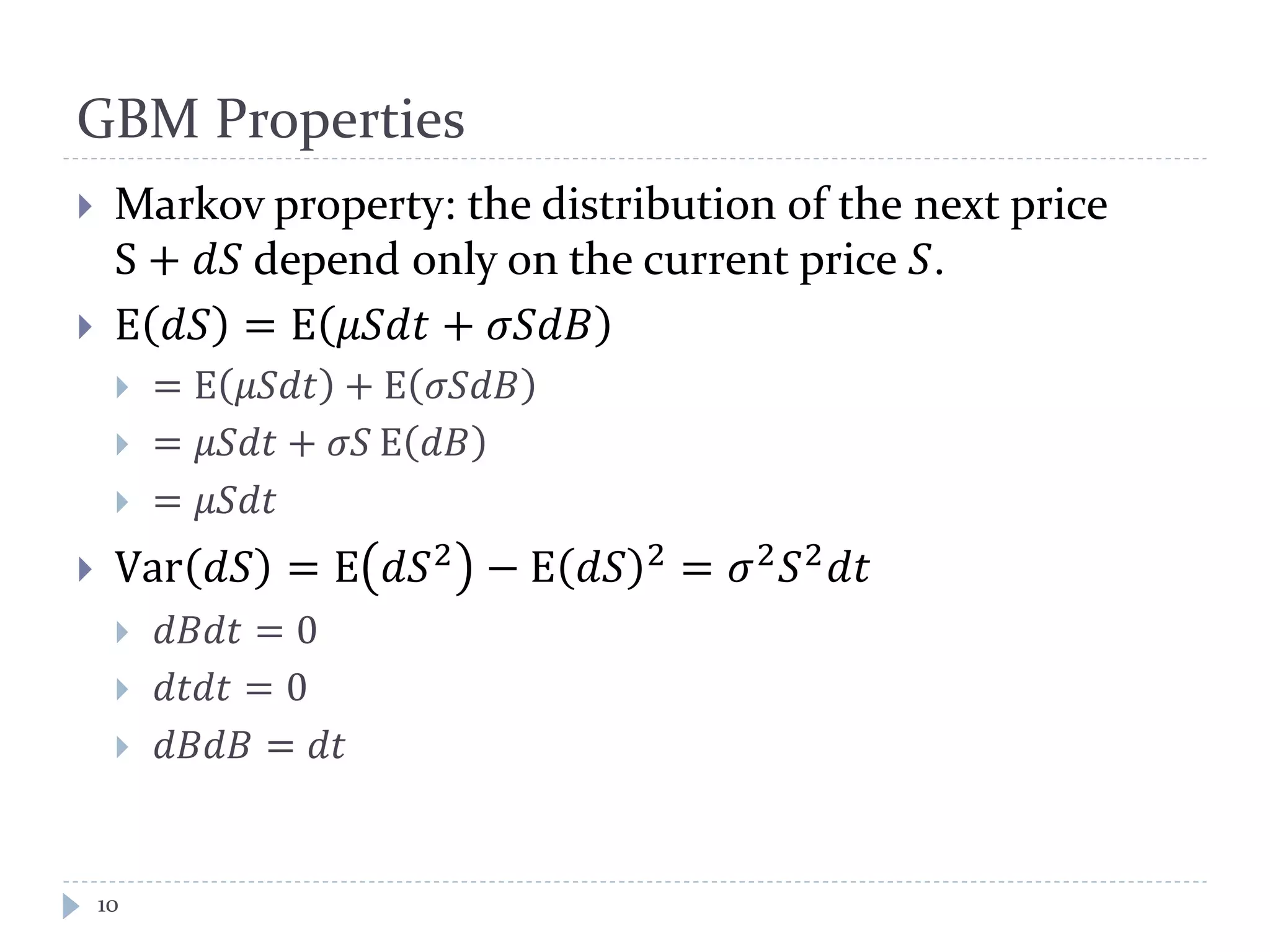

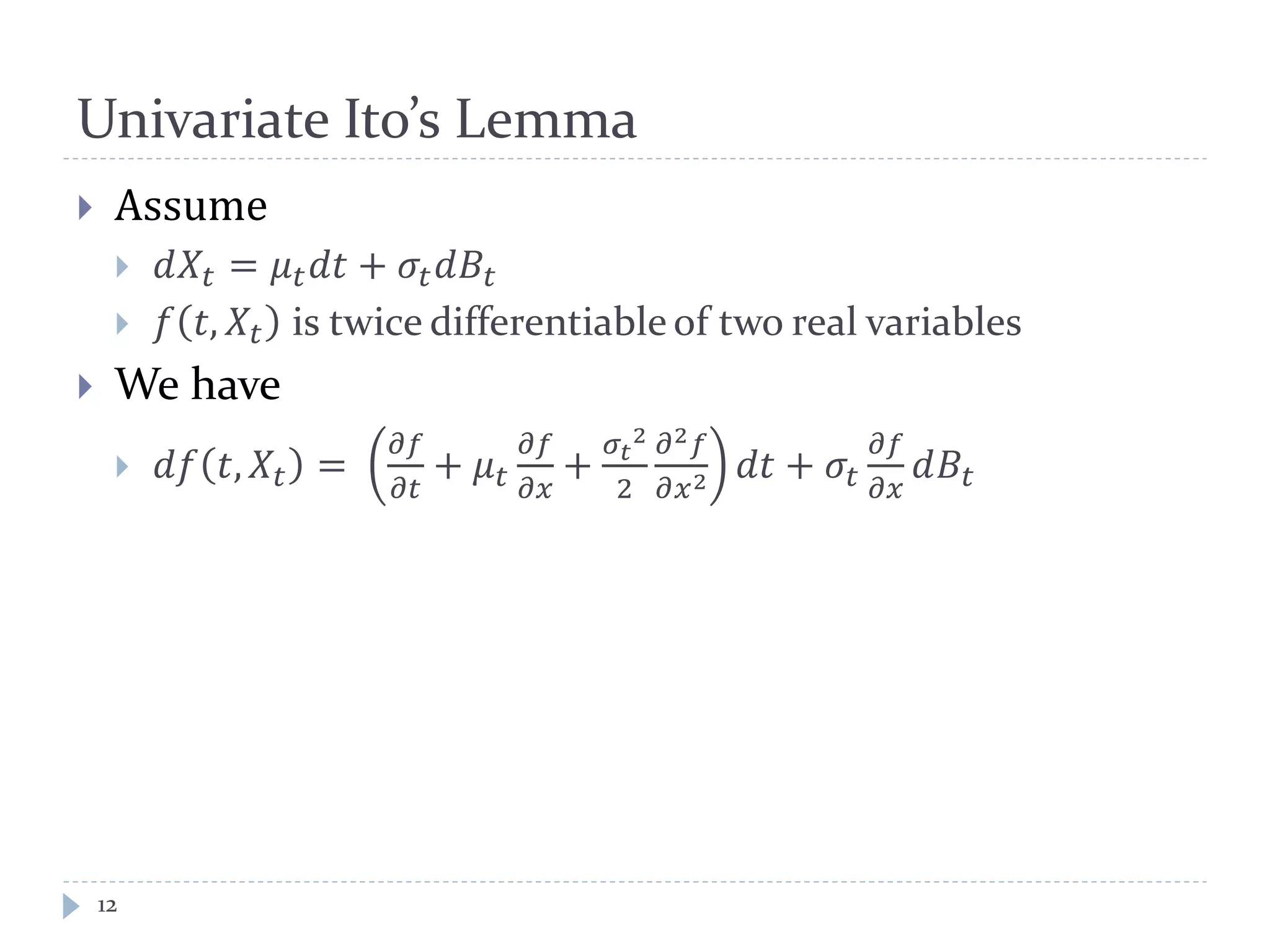

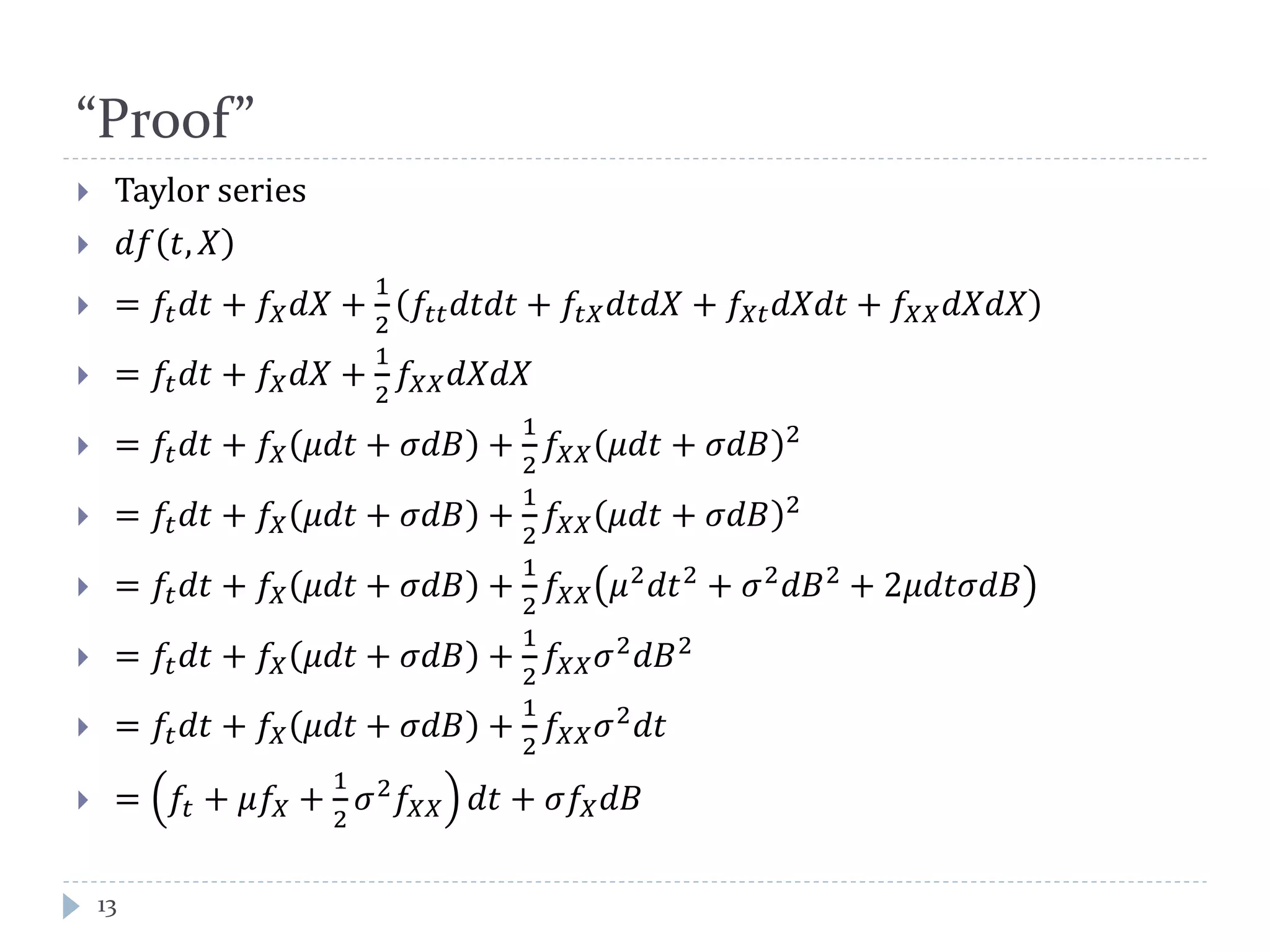

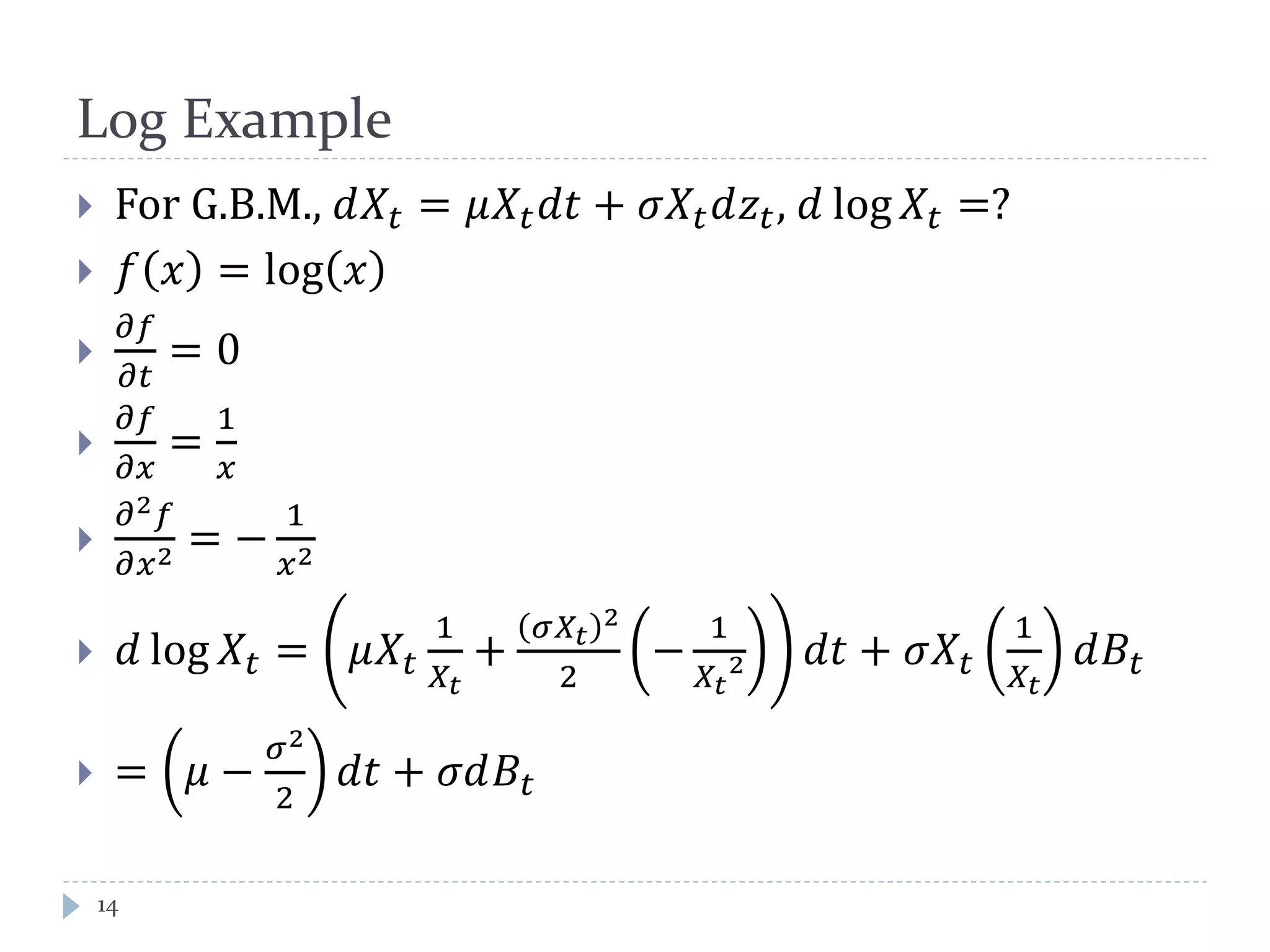

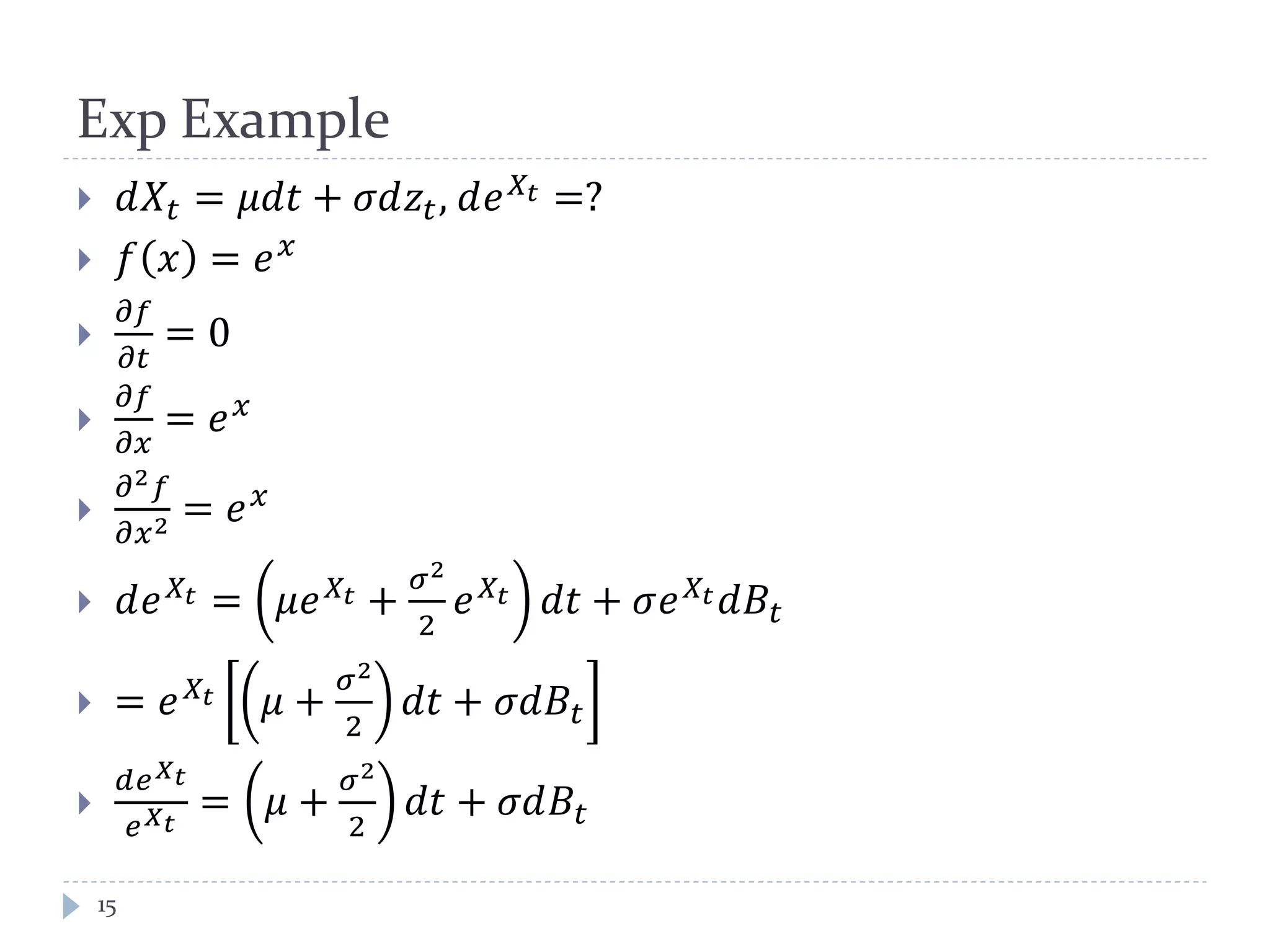

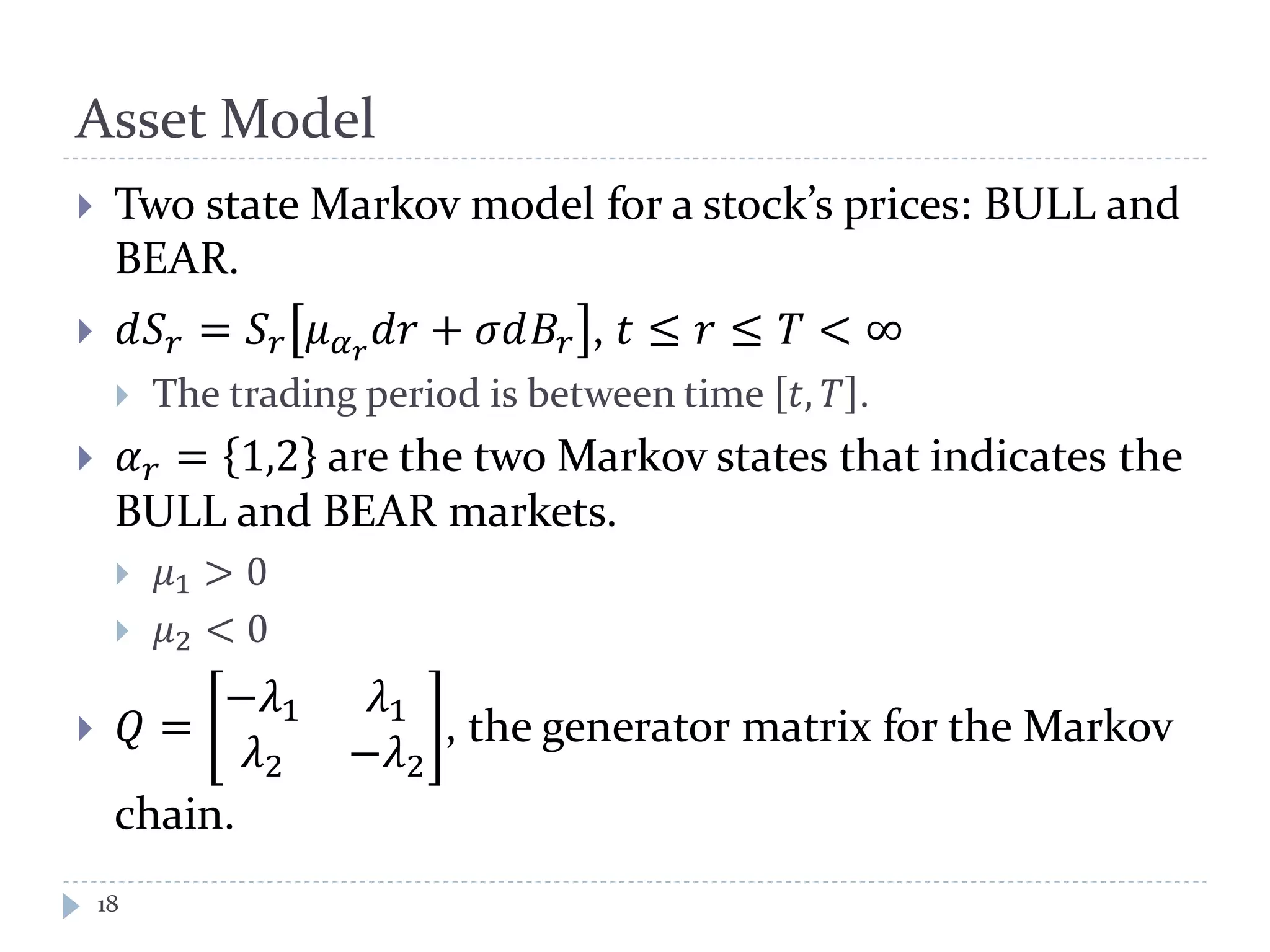

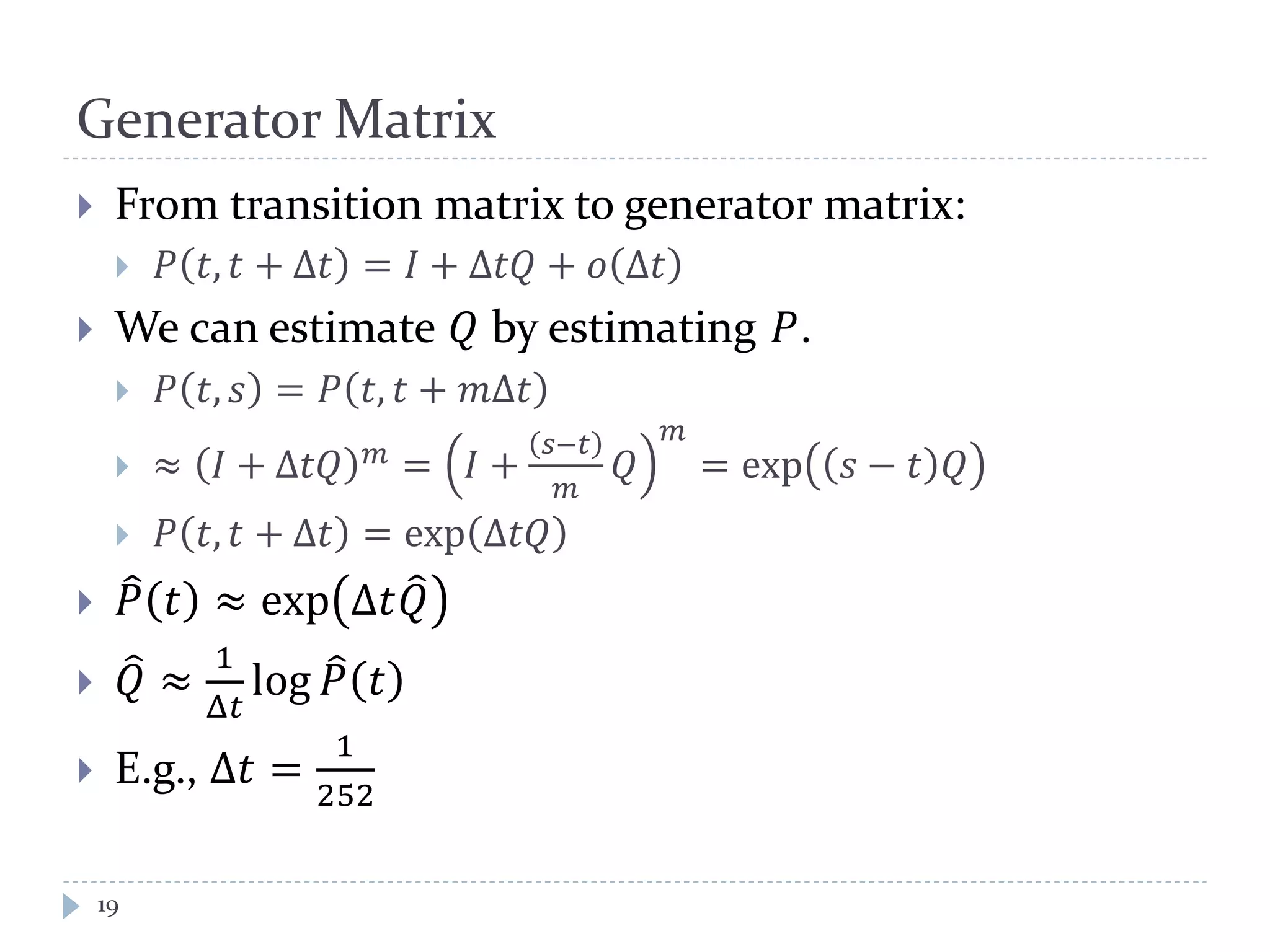

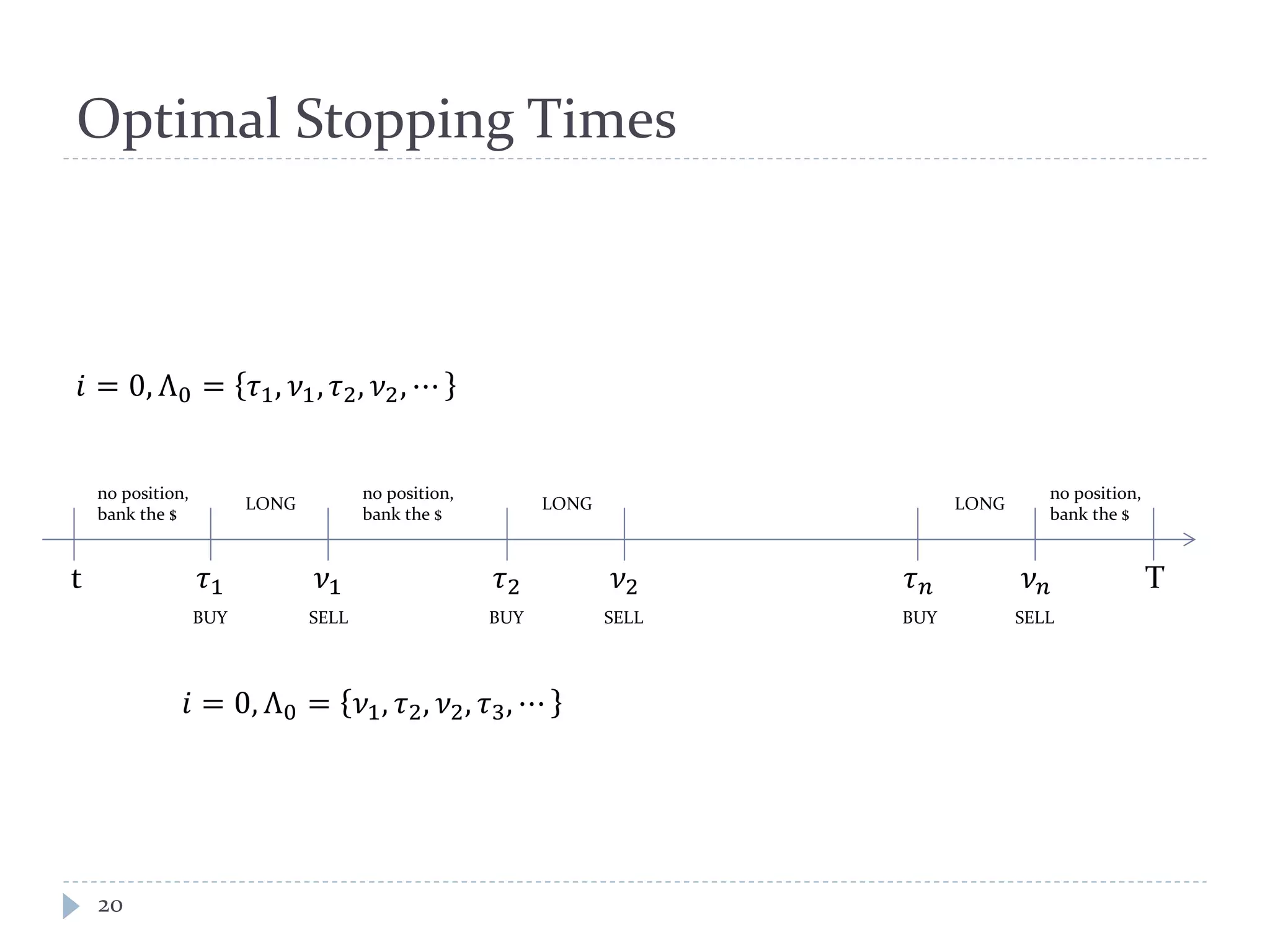

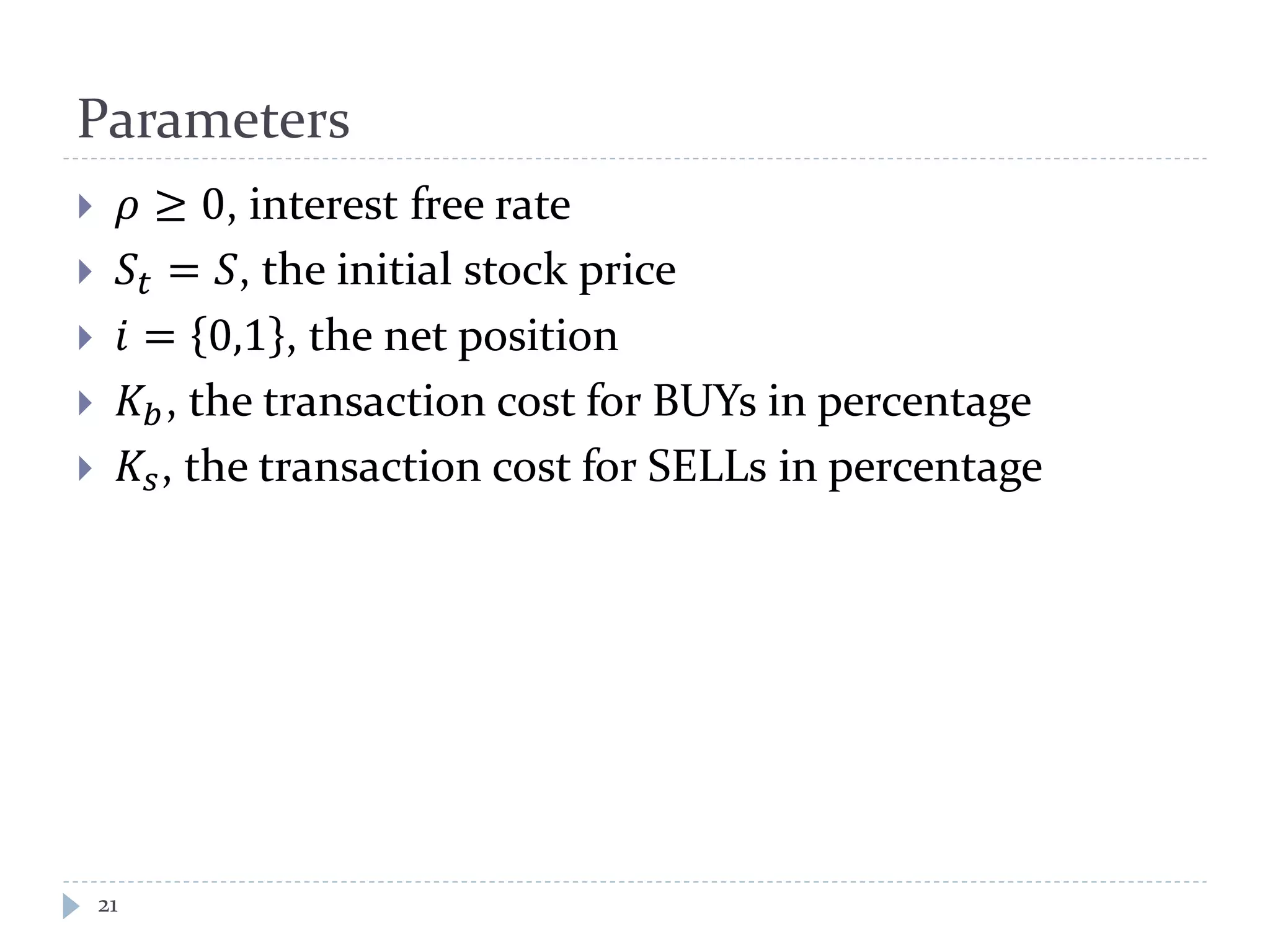

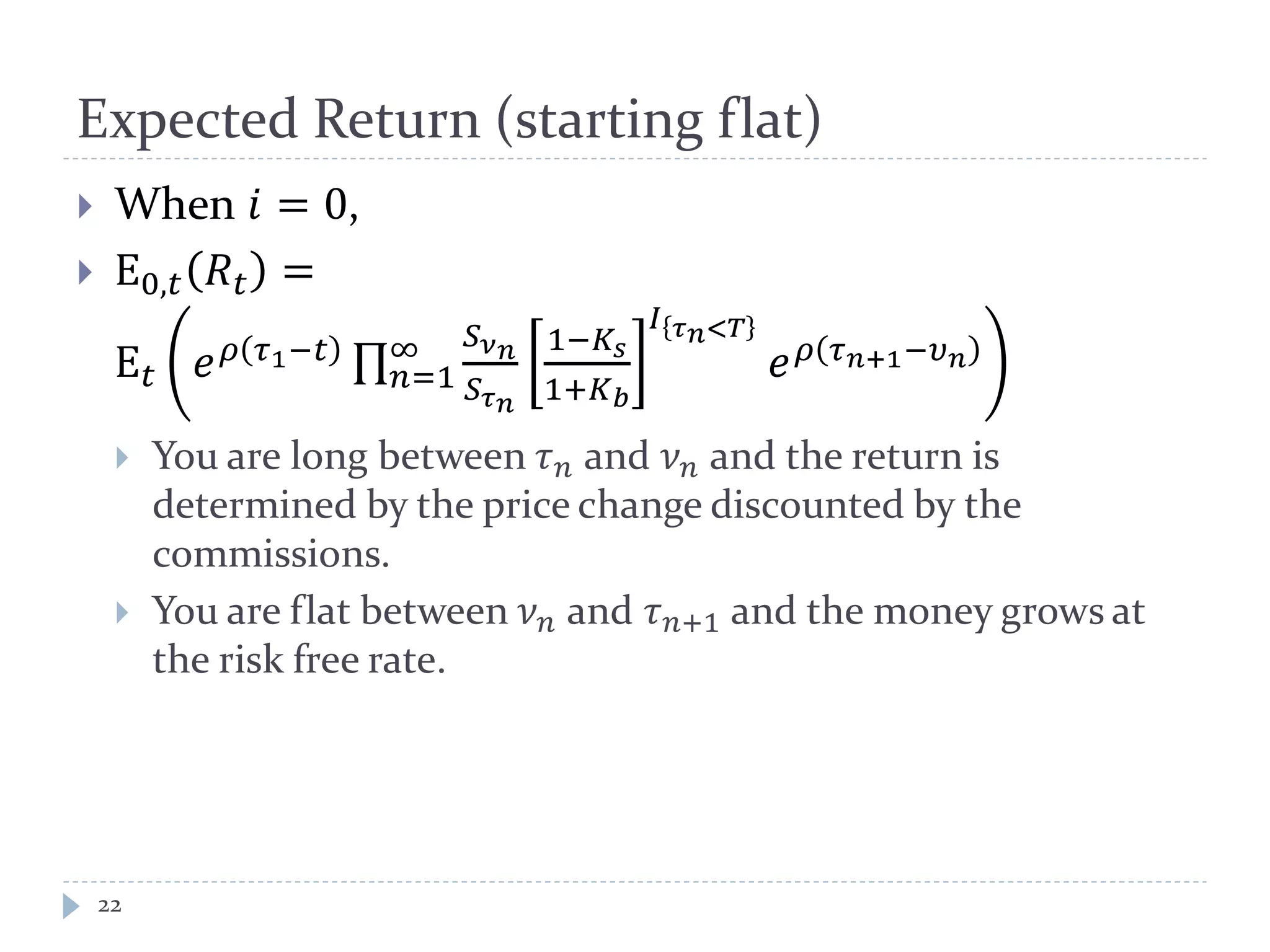

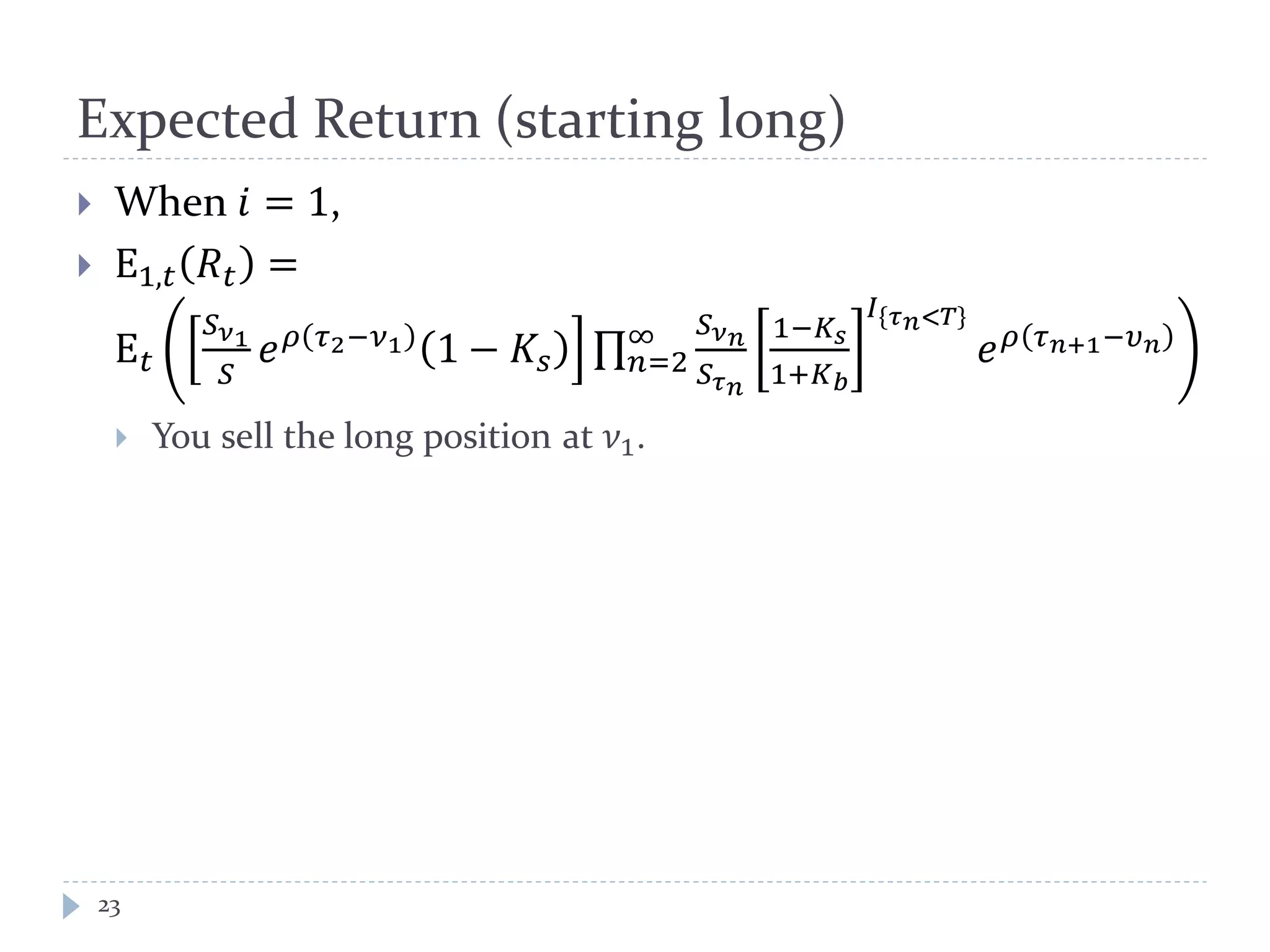

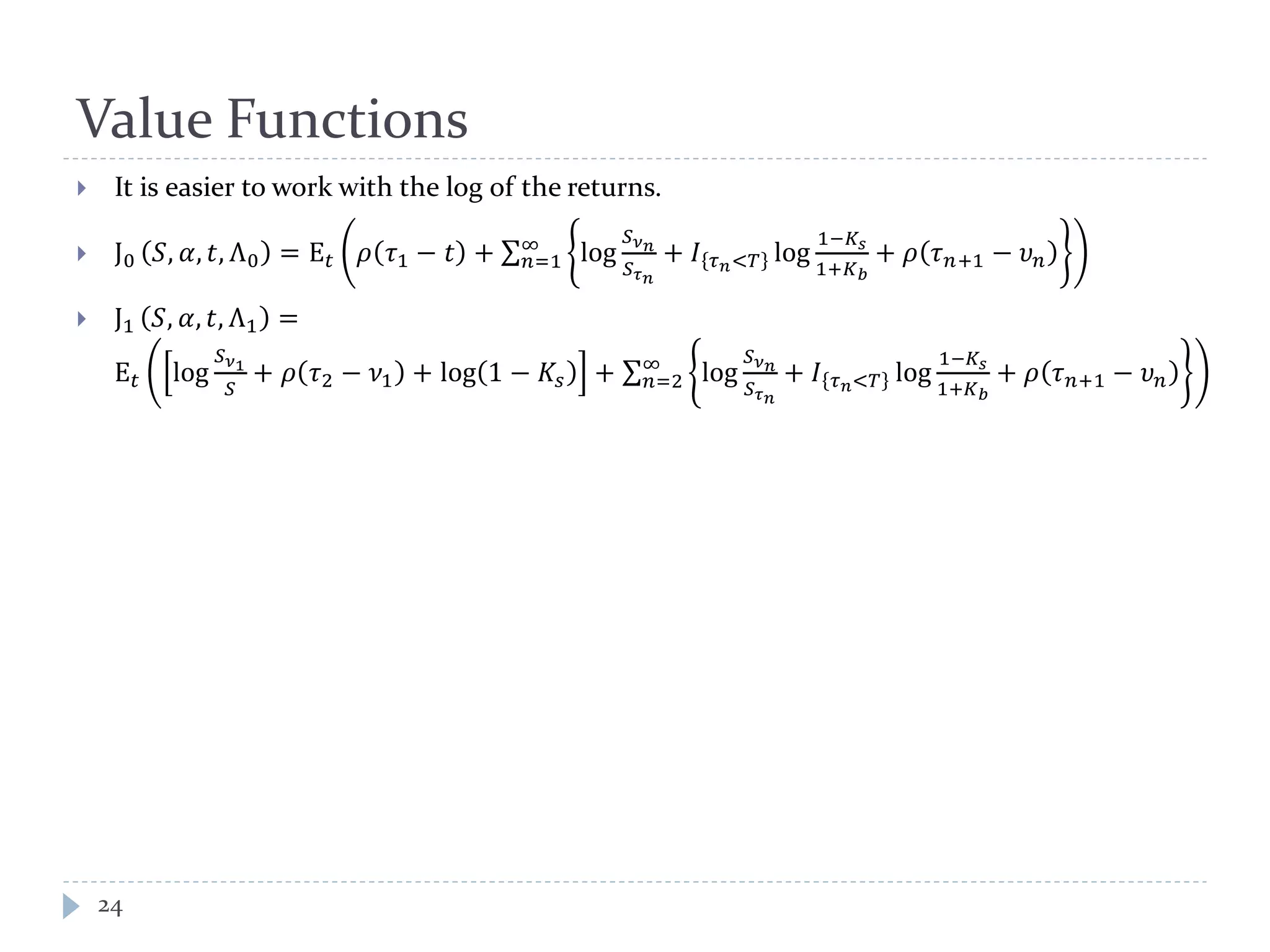

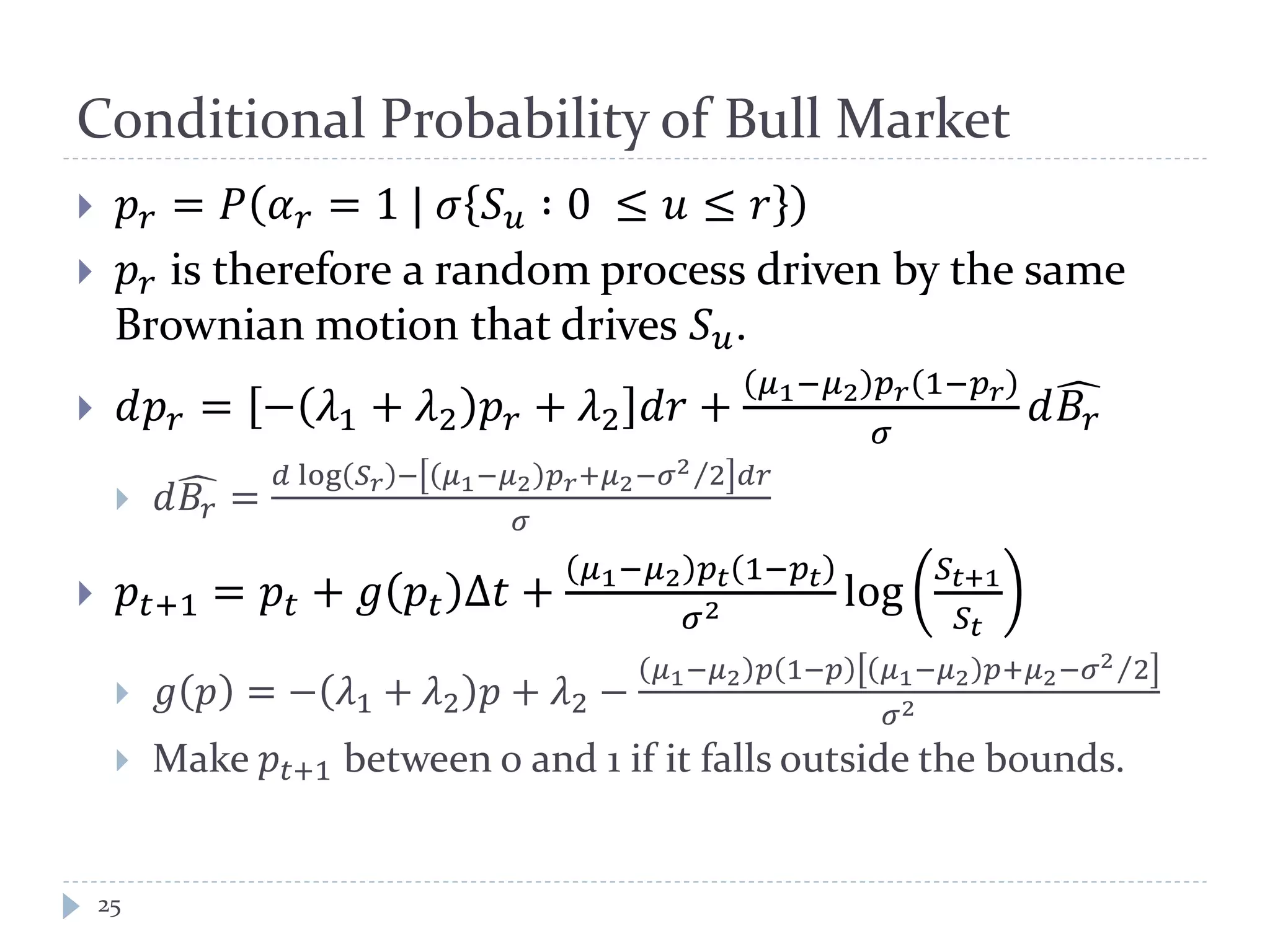

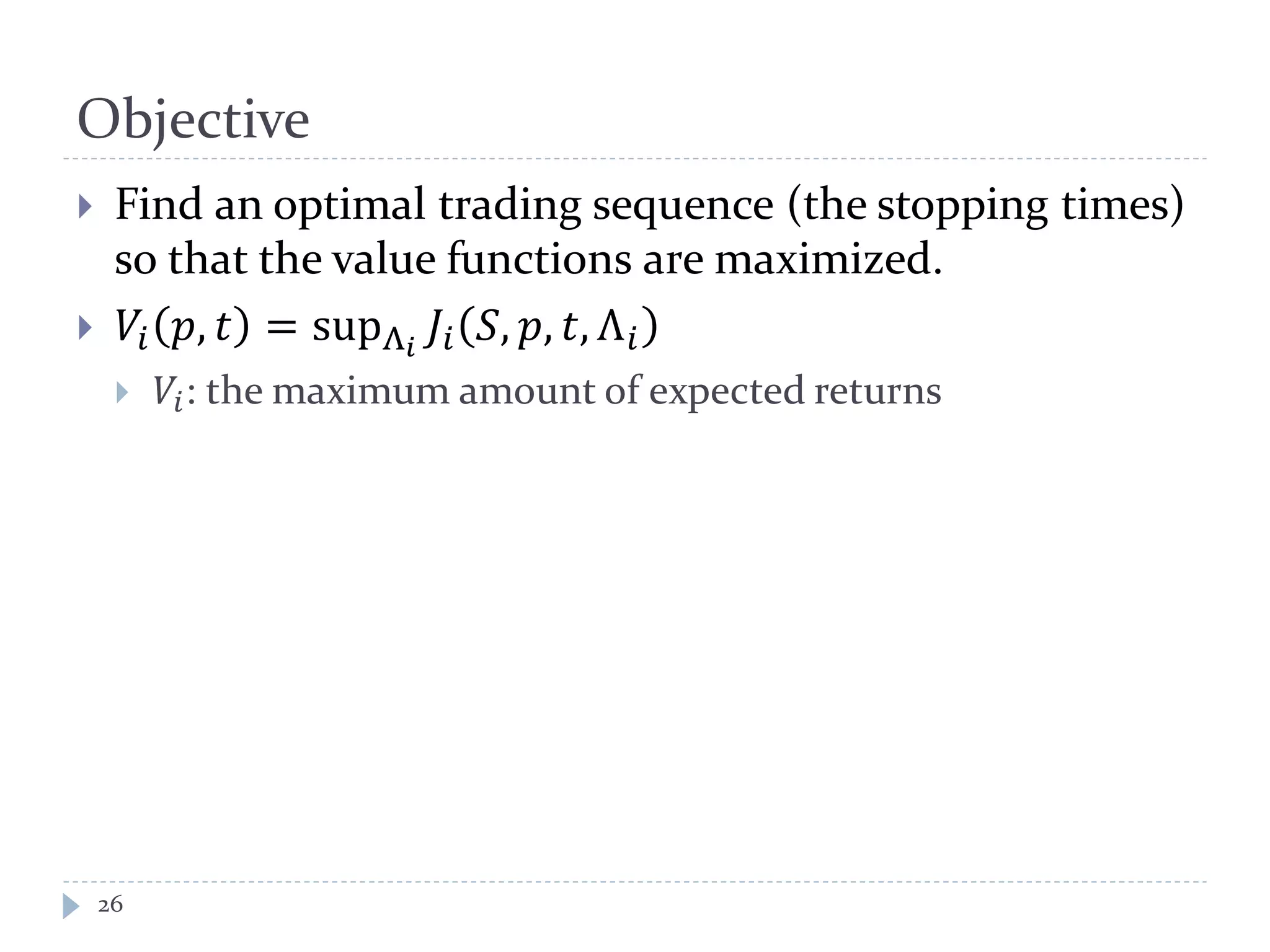

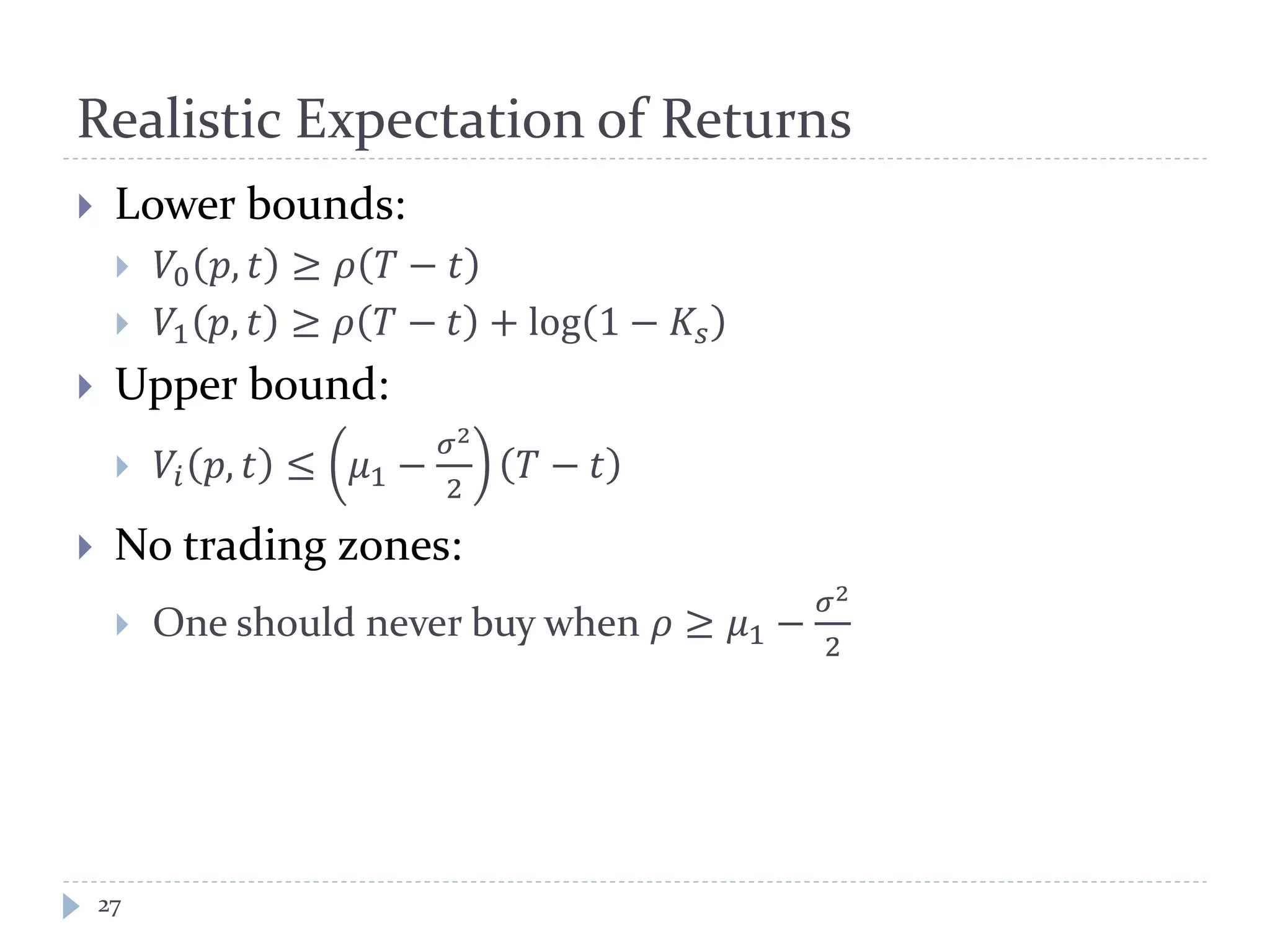

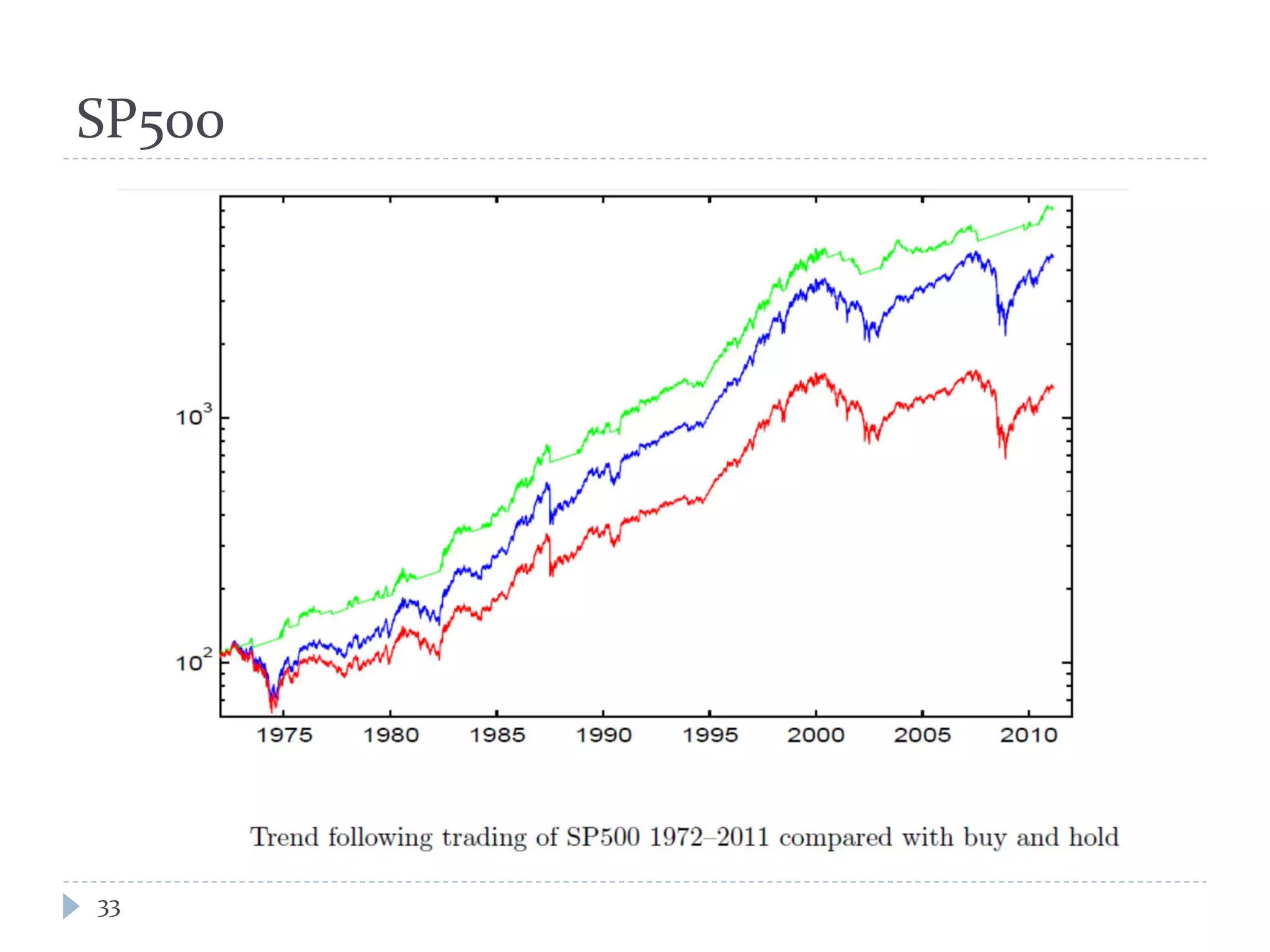

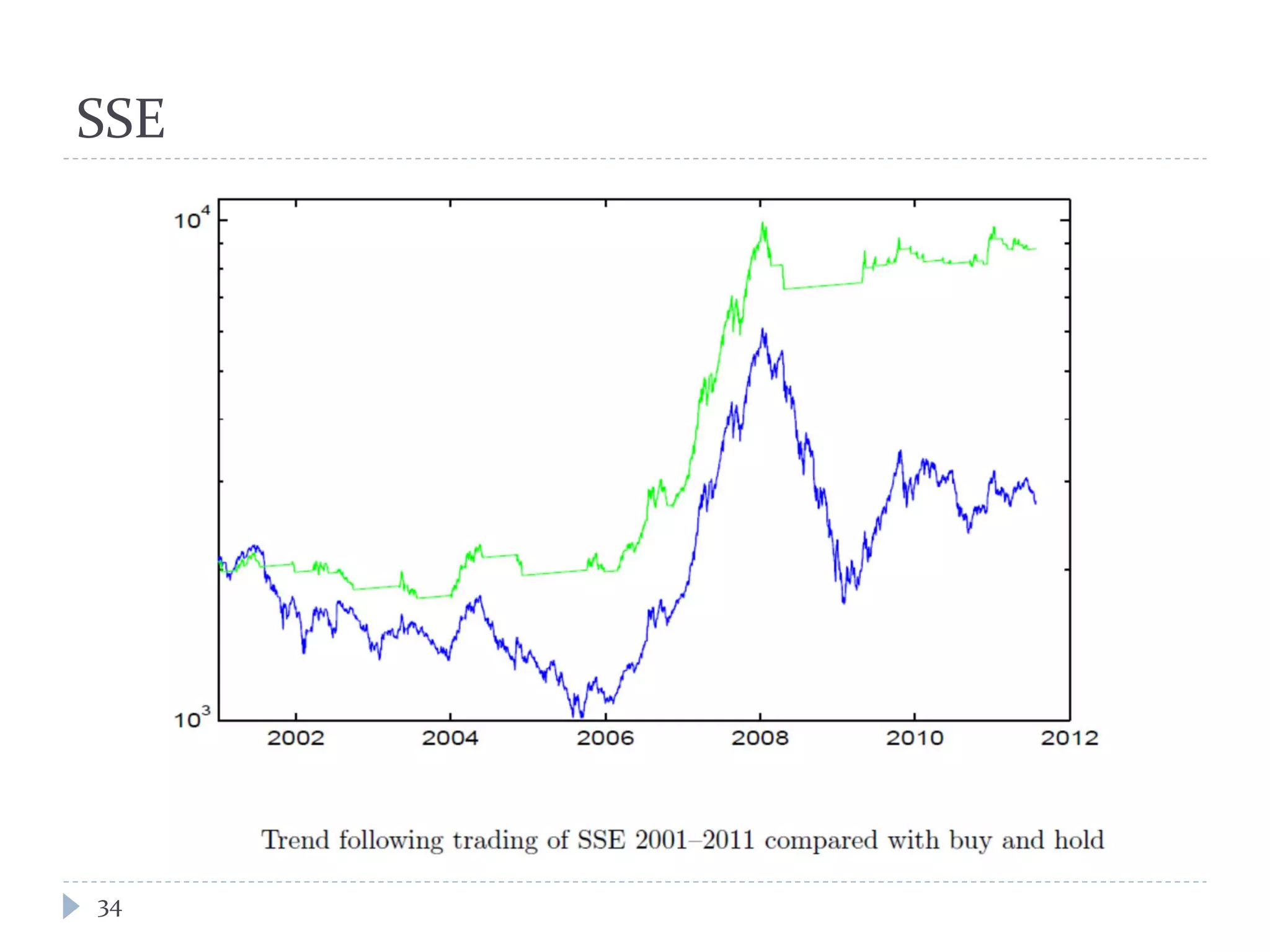

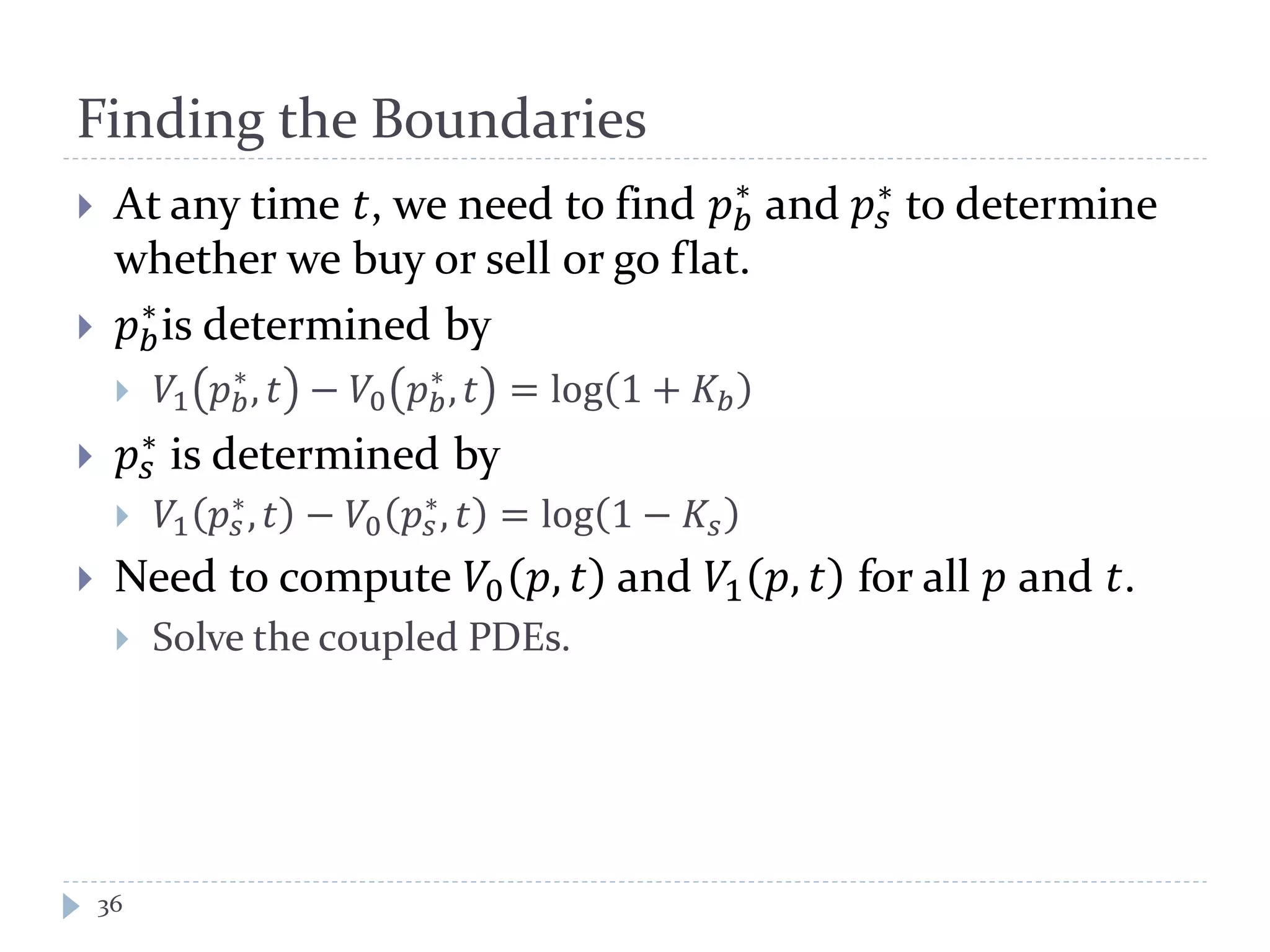

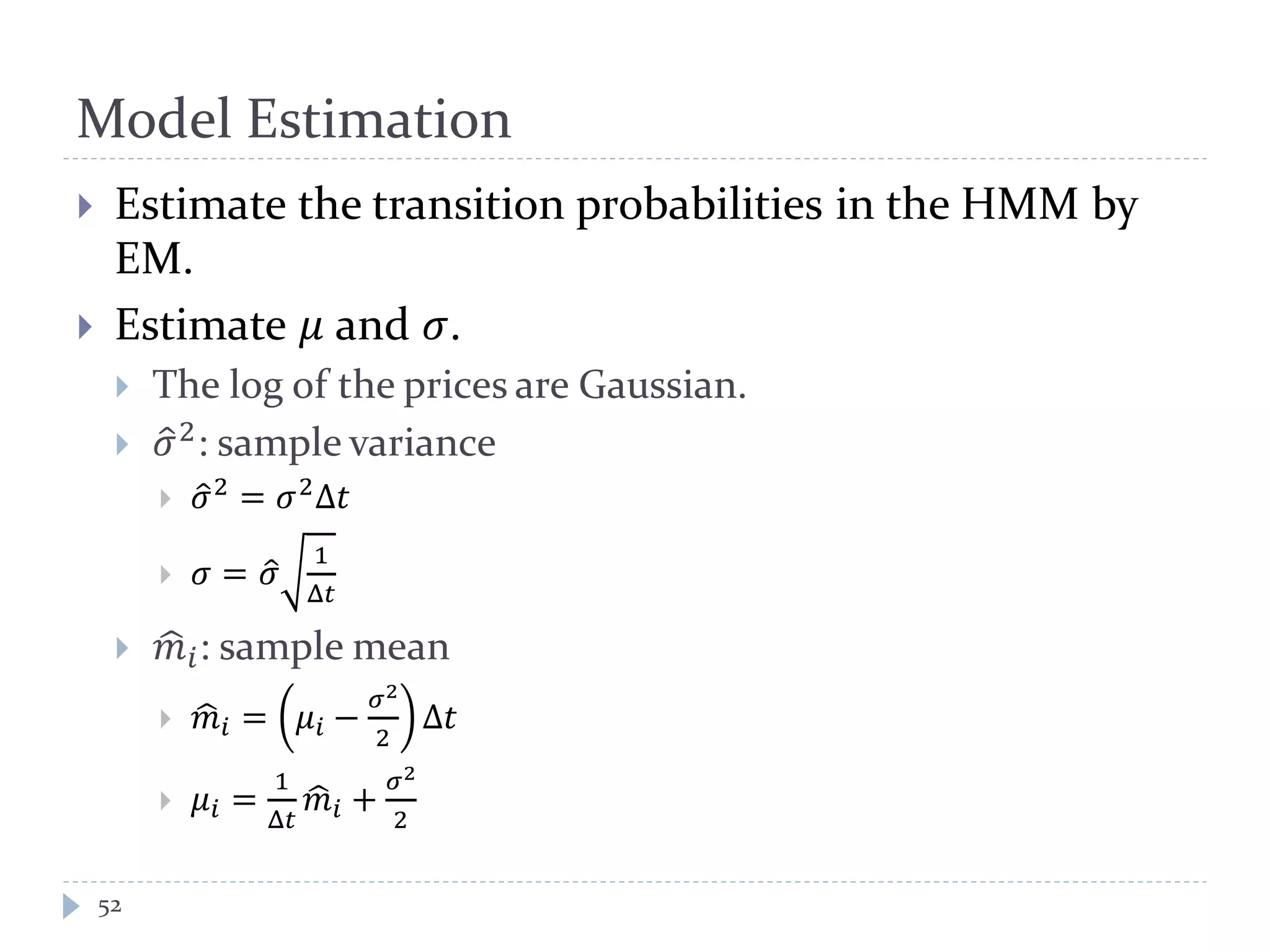

This document provides an introduction to trend following strategies in algorithmic trading. It discusses Brownian motion and stochastic calculus concepts needed to model asset price movements. Geometric Brownian motion is presented as a model for asset price changes over time. Optimal trend following strategies seek to identify the optimal times to buy and sell an asset to profit from trends while minimizing transaction costs. The strategy parameters and expected returns are defined.