The document discusses algorithms and data structures. It begins with two quotes about programming and algorithms. It then provides pseudocode for naive and optimized recursive Fibonacci algorithms, as well as an iterative dynamic programming version. It also covers dynamic programming approaches for calculating Fibonacci numbers, Catalan numbers, the chessboard traversal problem, the rod cutting problem, longest common subsequence, and assembly line traversal. The key ideas are introducing dynamic programming techniques like memoization and bottom-up iteration to improve the time complexity of recursive algorithms from exponential to polynomial.

![Fibonacci pseudocode

Naïve recursive version (Θ 2𝑛 )

Fibo(n)

if n = 0 then return 1

return Fibo(n-1)+Fibo(n-2)

DP smart recursive version (Θ 𝑛 )

Fibo(n, f)

if f[n] exists then return f[n]

if n = 0 or n = 1 then

f[n] = 1

return 1

sum = Fibo(n-1) + Fibo(n-2)

f[n] = sum

return sum](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/week6-240312173430-a7d01c0c/85/Applied-Algorithms-and-Structures-week999-2-320.jpg)

![Fibonacci pseudocode

DP iterative version (Θ 𝑛 )

Fibo(n)

f[0] = f[1] = 1

for i = 2 to n

f[i] = f[i-1] + f[i-2]

return f[n]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/week6-240312173430-a7d01c0c/85/Applied-Algorithms-and-Structures-week999-3-320.jpg)

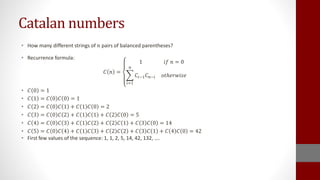

![Catalan numbers

• Dynamic programming pseudocode:

Catalan(n)

table[0] = 1

for i = 1 to n+1

sum = 0

for j = 0 to i-1

sum += table[j]*table[i-j-1]

table[i] = sum

return table[n]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/week6-240312173430-a7d01c0c/85/Applied-Algorithms-and-Structures-week999-9-320.jpg)

![Chessboard traversal

This is a maximization optimization problem. You are given an 𝑛 × 𝑛 table 𝑝 of profits.

Here is top down recursive definition of maximal profit:

𝑞(𝑖, 𝑗) =

0 𝑗 < 1 or 𝑗 > 𝑛

𝑝[𝑖, 𝑗] if 𝑖 = 1

𝑝 𝑖, 𝑗 + max{𝑞(𝑖 − 1, 𝑗 − 1), 𝑞(𝑖 − 1, 𝑗), 𝑞(𝑖 − 1, 𝑗 + 1)} otherwise

q(i,j)

if j < 1 or j > n then return 0

else if i = 1 then return p[i,j]

else return p[i,j] + max(q(i-1,j-1), q(i-1,j), q(i-1,j+1))

This algorithm would take Θ(2𝑛

) time. Show this with a recursion tree.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/week6-240312173430-a7d01c0c/85/Applied-Algorithms-and-Structures-week999-12-320.jpg)

![Chessboard traversal

Instead of beginning by trying to compute the maximal profit path of length 𝑛, we will

compute maximal profits for paths of length 1, then paths of length 2, and so forth.

We’ll use a 2-dimensional table called 𝑞.

The value of 𝑞[𝑖, 𝑗] is the maximum profit one can earn for every path that ends at

square 𝑖, 𝑗.

Represent the computation of 𝑞 with an 𝑛 × 𝑛 table. Fill the table row-by-row. Begin

by filling row 1 with the values from the profit table (𝑝).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/week6-240312173430-a7d01c0c/85/Applied-Algorithms-and-Structures-week999-13-320.jpg)

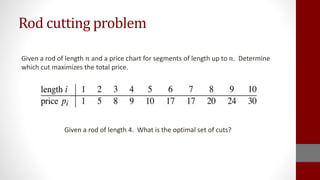

![Rod cutting problem

We can simplify the optimization by realizing that we need to know where the leftmost

cut will be in an optimal cutting of the rod. Given that, we get the following recurrence

relation for calculating 𝑟[𝑘], the maximum profit obtainable from a rod of length 𝑘:

𝑟 𝑘 =

0 if 𝑘 = 0

max

1≤𝑖≤𝑘

{𝑝 𝑖 + 𝑟 𝑘 − 𝑖 } otherwise

The index 𝑖 in the maximum calculation is the location of the leftmost cut.

Calculating this recurrence from the top-down is done by the pseudocode on the next

slide.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/week6-240312173430-a7d01c0c/85/Applied-Algorithms-and-Structures-week999-17-320.jpg)

![How does the bottom-up approach work?

The array element 𝑝[𝑖] holds the price for a segment of length 𝑖. The array element

𝑟[𝑖] holds the optimal price for a rod of length 𝑖.

Compute the optimal solution for a rod of length 1.

Compute the optimal solution for a rod of length 2.

…

Computing the optimal solution for a rod of length 𝑗 means trying each of the possible

𝑗 − 1 cuts. We think of each cut as being the first one (leftmost).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/week6-240312173430-a7d01c0c/85/Applied-Algorithms-and-Structures-week999-22-320.jpg)

![LCS: recursive solution

We can use the optimal substructure formulas to construct a recurrence relation for

𝑐[𝑖, 𝑗], which is the length of the LCS for the pair 𝑋𝑖 and 𝑌

𝑗:

𝑐 𝑖, 𝑗 =

0 𝑖𝑓 𝑖 = 0 𝑜𝑟 𝑗 = 0

𝑐 𝑖 − 1, 𝑗 − 1 + 1 𝑖𝑓 𝑖, 𝑗 > 0 𝑎𝑛𝑑 𝑥𝑖 = 𝑦𝑗

max{𝑐 𝑖, 𝑗 − 1 , 𝑐 𝑖 − 1, 𝑗 } 𝑖𝑓 𝑖, 𝑗 > 0 𝑎𝑛𝑑 𝑥𝑖 ≠ 𝑦𝑗

There are many possible sub-problems but the formula only considers a few.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/week6-240312173430-a7d01c0c/85/Applied-Algorithms-and-Structures-week999-26-320.jpg)

![LCS: computing using DP

Note that the 𝑐 values may be placed into a table of size 𝑚 × 𝑛.

Index the rows from the top to bottom 0 to 𝑚, index the columns from left to right 0 to

𝑛. Note that computing 𝑐[𝑖, 𝑗] requires table values to its left, above it, or left and

above.

So fill the table row-by-row starting at row 0.

On the board: An example with the sequences 𝑋 = 〈𝐴, 𝐵, 𝐶, 𝐵, 𝐷, 𝐴, 𝐵〉 and 𝑌 =

〈𝐵, 𝐷, 𝐶, 𝐴, 𝐵, 𝐴〉.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/week6-240312173430-a7d01c0c/85/Applied-Algorithms-and-Structures-week999-27-320.jpg)

![Assembly line traversal

Treating the recurrence relation as a way to define values in a pair of tables, fill each

table bottom-up, that is, starting at the table entry at position 1, rather than filling it by

starting at position 𝑛.

Let 𝑓1 1 = 𝑒1 + 𝑎1,1 and 𝑓2 1 = 𝑒2 + 𝑎2,1.

Have a for-loop indexing 𝑗 from 2 to 𝑛. Inside the for-loop compute 𝑓1[𝑗] and 𝑓2[𝑗].

From the recurrence, each of these relies only values in the table to the left, that is,

values that have already been computed.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/week6-240312173430-a7d01c0c/85/Applied-Algorithms-and-Structures-week999-33-320.jpg)