The document discusses national and international responses to cybercrime. It provides background on computer fraud statistics in the UK and Ireland. It discusses early cases of unauthorized computer access in the UK, including R v Gold & Schifreen, and how this led to the Computer Misuse Act of 1990. It then covers the Council of Europe Cybercrime Convention, which aims to harmonize cybercrime laws. Ireland has signed this convention. The document also discusses recommendations and guidelines from organizations like the OECD concerning cybersecurity policies and information sharing.

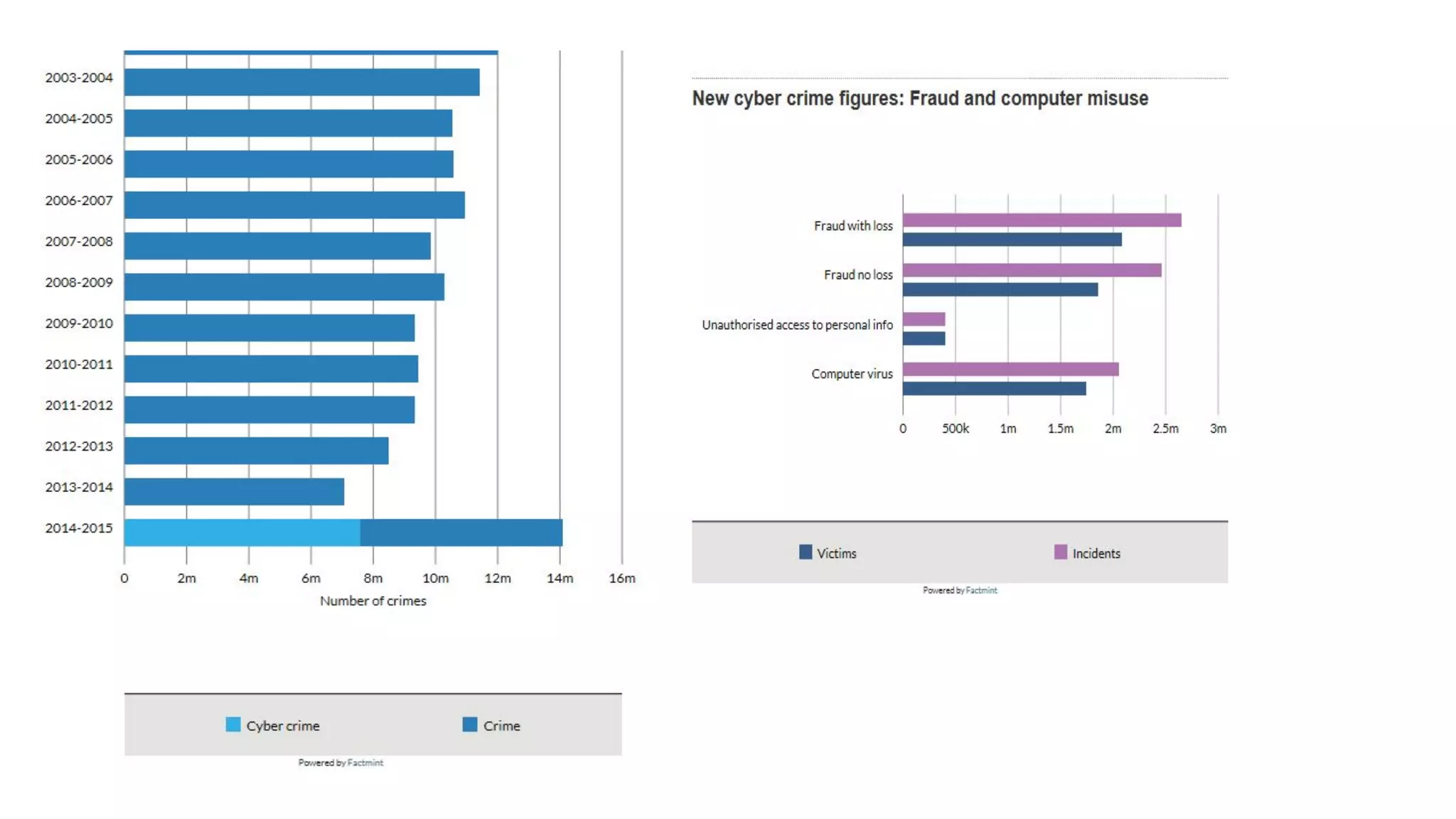

![R V GOLD & SCHIFREEN [1988]

(HL).

Robert Schifreen and Stephen Gold, using conventional home

computers and modems in late 1984 and early 1985,

gained unauthorized access to British Telecom's Prestel interactive view

data service.

While at a trade show, Schifreen, by doing what later became known

as shoulder surfing, had observed the password of a Prestel engineer:

the username was 22222222 and the password was 1234. This later

gave rise to subsequent accusations that BT had not

taken security seriously.

Armed with this information, the pair explored the system, even

gaining access to the personal message box of Prince Philip, Duke of

Edinburgh.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cybercrimelegislationpart1-210225162149/75/International-Cybercrime-Part-1-10-2048.jpg)

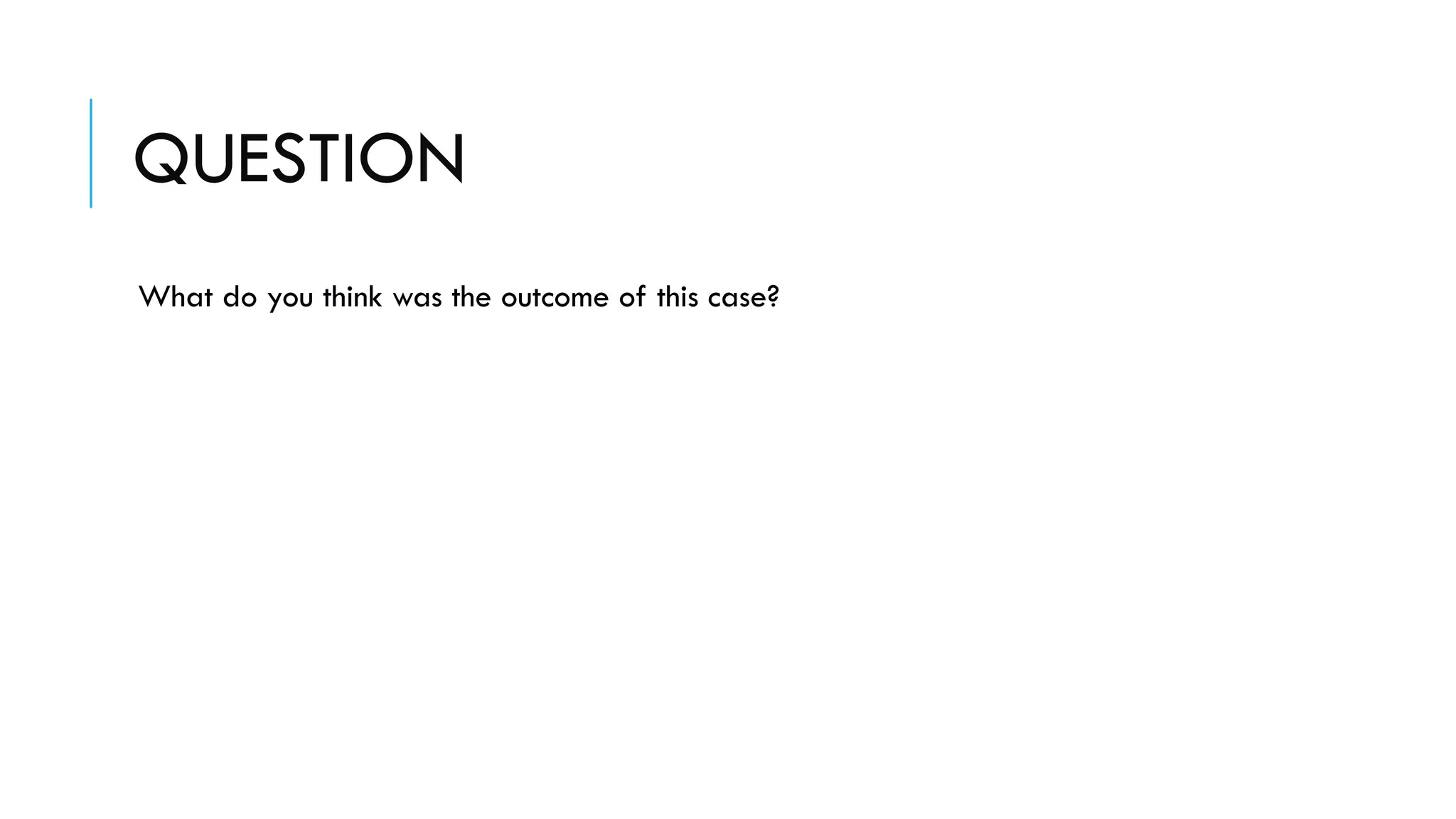

![R V GOLD & SCHIFREEN [1988]

(HL).

Unknown to Schifreen and Gold, the Prestel computer network operated

on a distributed basis and was intended to act as a hot standby in the

event of the UK going to war — in the event that the primary UK

military computers were down, the Prestel network could be used to

control and launch the UK's nuclear missiles.

Following discussions with GCHQ and MI6, it was decided to investigate

Schifreen and Gold's activities, notwithstanding that, as freelancers for

Micronet, a joint venture between BT and a major publishing house, the

pair had informed their superiors of their discovery.

Prestel installed monitors on both of the pair's modem connections and,

acting on the information obtained, decided it was in the best interests

of national security to arrest them.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cybercrimelegislationpart1-210225162149/75/International-Cybercrime-Part-1-11-2048.jpg)

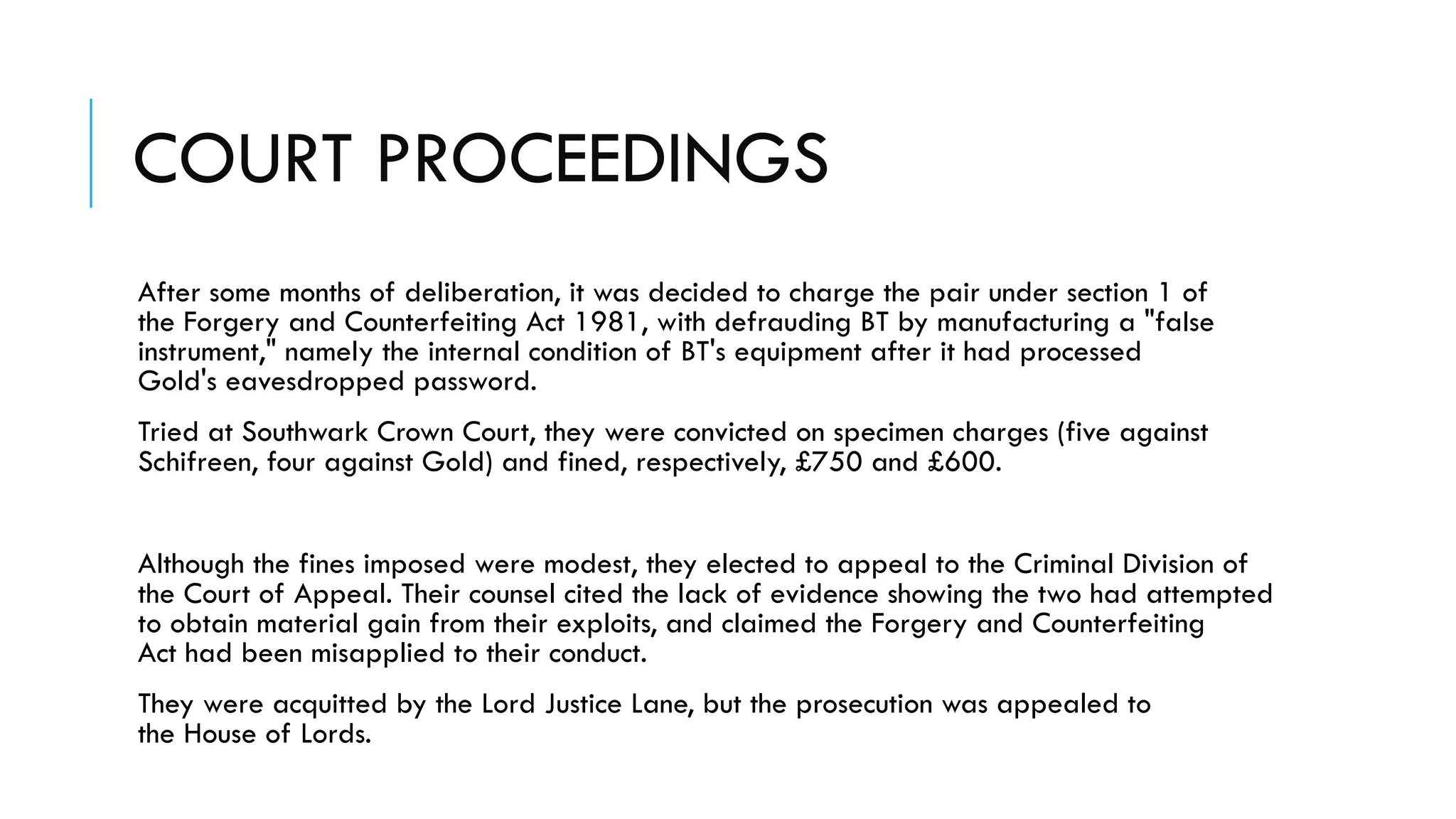

![HOUSE OF LORDS DECISION

In 1988, the Lords upheld the acquittal. Lord Brandon said;

“We have accordingly come to the conclusion that the language of the Act was not

intended to apply to the situation which was shown to exist in this case. The

submissions at the close of the prosecution case should have succeeded. It is a

conclusion which we reach without regret. The Procrustean attempt[2]

to force these

facts into the language of an Act not designed to fit them produced grave

difficulties for both judge and jury which we would not wish to see repeated. The

appellants' conduct amounted in essence, as already stated, to dishonestly

gaining access to the relevant Prestel data bank by a trick. That is not a criminal

offence. If it is thought desirable to make it so, that is a matter for the legislature

rather than the courts.”](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cybercrimelegislationpart1-210225162149/75/International-Cybercrime-Part-1-14-2048.jpg)

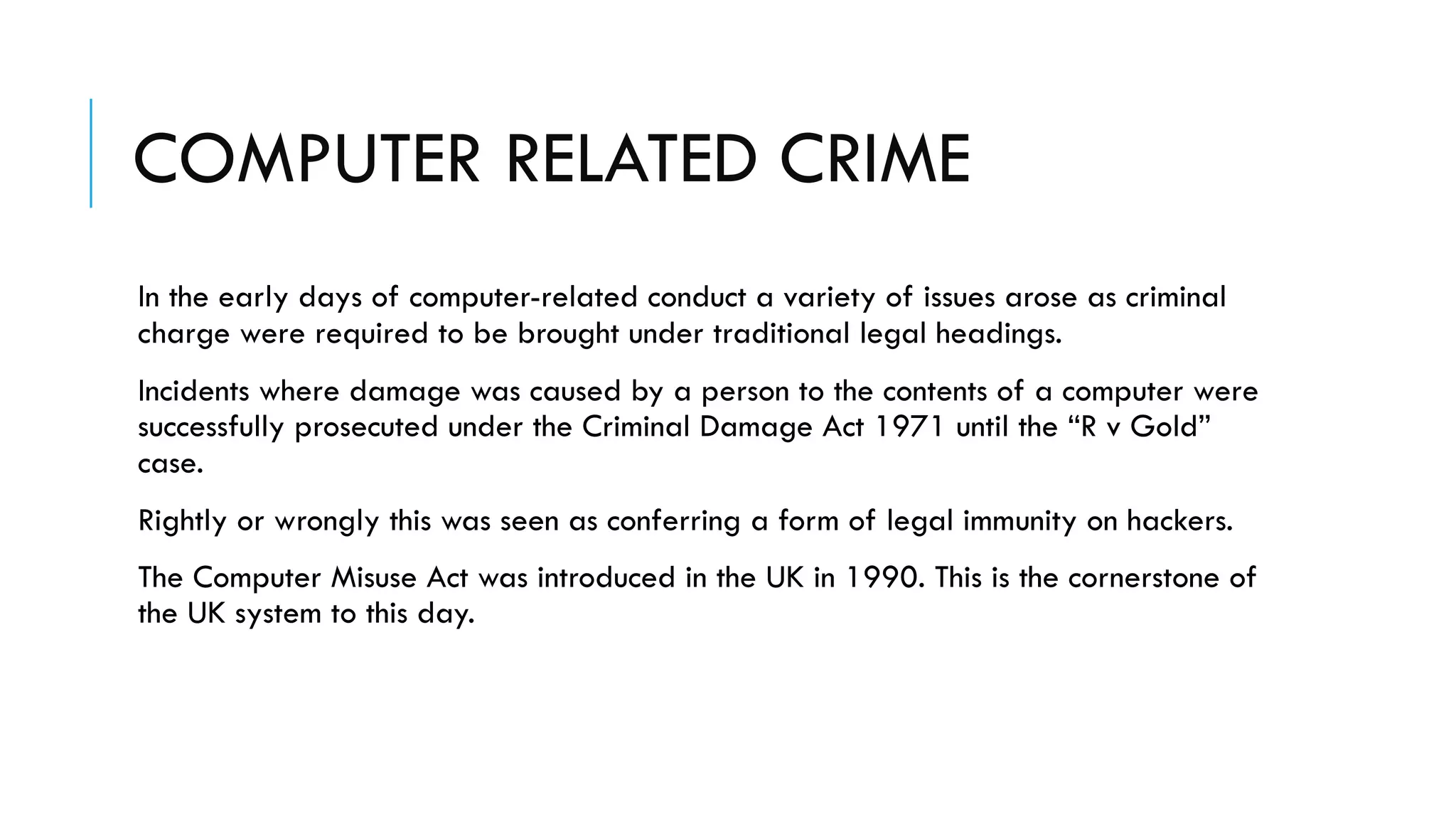

![IMPLEMENTATION PLAN

• Enacting a comprehensive set of substantive criminal, procedural and mutual

assistance legal measures to combat cybercrime and ensure cross-borders

co-operation. These should be at least as comprehensive as, and consistent with,

the Council of Europe Convention on Cybercrime (2001).

• Identifying national cybercrime units and international high-technology assistance

points of contact and creating such capabilities to the extent they do not already

exist; and

• Establishing institutions that exchange threat and vulnerability assessments [such as

national CERTs (Computer Emergency Response Teams)].

• Developing closer co-operation between government and business in the fields of

information security and fighting cybercrime.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cybercrimelegislationpart1-210225162149/75/International-Cybercrime-Part-1-36-2048.jpg)

![ENISA

• Identifying national cybercrime units and international high-technology assistance

points of contact and creating such capabilities to the extent they do not already

exist; and

Establishing institutions that exchange threat and vulnerability assessments [such as

national CERTs (Computer Emergency Response Teams)].

Developing closer co-operation between government and business in the fields of

information security and fighting cybercrime.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cybercrimelegislationpart1-210225162149/75/International-Cybercrime-Part-1-50-2048.jpg)