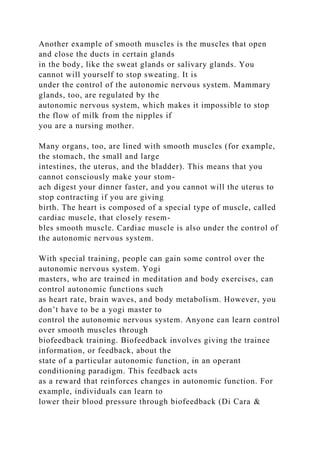

This document provides an overview of the nervous system, including its organization into the central and peripheral systems, which incorporate the somatic and autonomic divisions. It explains the roles of sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems and introduces the structure and function of neurons and glial cells. Additionally, it touches on conditions such as multiple sclerosis and details the effects of activation in both sympathetic and parasympathetic states.

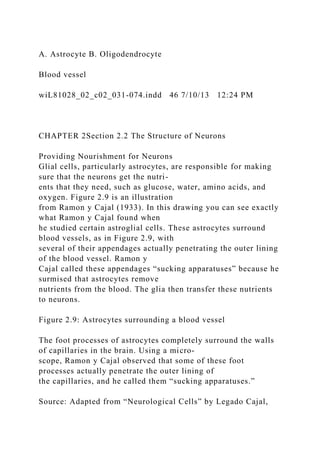

![CHAPTER 2Section 2.2 The Structure of Neurons

information enters the dorsal areas. What can you predict about

damage to the spinal cord? Dam-

age to the ventral part of the spinal cord will produce motor

dysfunction, whereas damage to the

dorsal part will impair sensation. Obviously, damage to the

entire spinal cord, as when the spinal

cord is totally transected or torn apart, will affect both sensory

and motor functions.

Sensory neurons in the head and neck send their axons directly

to the brain, via cranial nerves,

which we will examine in Chapter 4. Therefore, damage to the

spinal cord does not affect sensory

or motor functions of the head. Damage to a cranial nerve will

impair the specific sense associ-

ated with that nerve. For example, damage to the olfactory

nerve, or cranial nerve I, will impair

the sense of smell, and injury to the optic nerve, also known as

cranial nerve II, will impair vision.

In the spinal cord an interneuron is a neuron that receives

information from one neuron and

passes it on to another neuron. That is, as its name implies

[inter means “between”], an inter-

neuron is situated between two other neurons. The axons and

dendrites of interneurons do not

extend beyond their cell clusters in the gray matter of the spinal

cord. See Figure 2.7 for their loca-

tion in the spinal cord.

Special Features of Neurons

As you’ve just learned, neurons are a unique type of cell. They](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/images-221108013517-7df3a4d0/85/Images-comCorbisLearning-ObjectivesAfter-completing-t-docx-25-320.jpg)

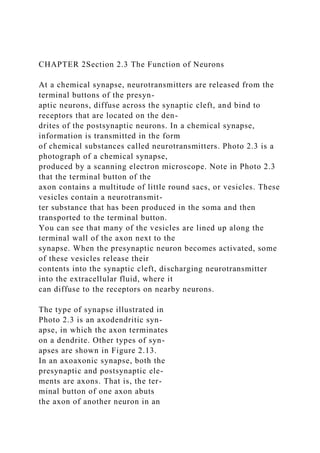

![Baby Amanda was nearly 15 months old when she was admitted

to a metropolitan hospital in a coma.

Shortly before the ambulance brought her to the hospital,

Amanda had been toddling happily around

the living room of her home, where she lived with her mother

and father. Unfortunately, someone had

left a recliner in its laid-back position, with its back down and

its footstool up. Amanda threw herself

down on the footstool, giggling. The weight of her body pushed

the footstool down, causing the chair

to automatically assume its upright position.

Amanda’s neck was trapped in the space between the footstool

and the chair, and when the chair

folded upright, the footstool squeezed against her neck,

obstructing the flow of blood to her brain.

Amanda’s mother was in the living room at the time of this

incident, and she raced over to the chair as

soon as she realized what had happened. It took her nearly 20

seconds to get Amanda free from the

chair. However, by that time, Amanda was purple in the face

and unconscious. Unable to revive her

baby, Amanda’s mother dialed 911 and summoned an

ambulance.

When Amanda arrived at the hospital, she was breathing on her

own but did not respond to any

stimulation whatsoever. She was examined by a team of

neurologists who determined that she was in

a coma. The anoxia [an- means “without,” and -oxia means

“oxygen”] caused by the compression of

the chair on her neck, which stopped the flow of blood to her

brain, damaged Amanda’s brain to such

an extent that she was not expected to regain consciousness.

Amanda remained in a vegetative state](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/images-221108013517-7df3a4d0/85/Images-comCorbisLearning-ObjectivesAfter-completing-t-docx-28-320.jpg)