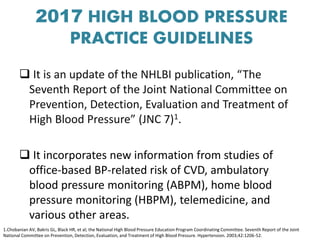

The document discusses updated guidelines for diagnosing and treating hypertension that were released in 2017. Some key points:

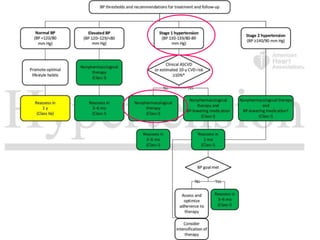

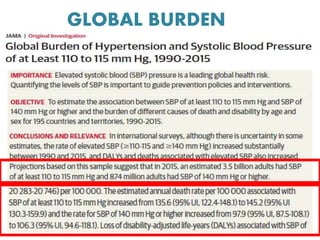

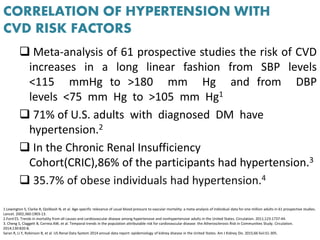

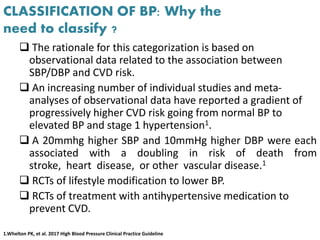

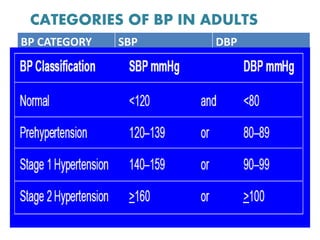

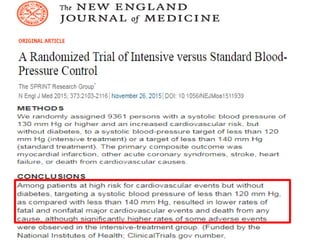

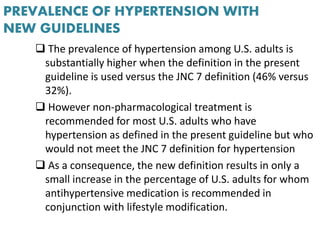

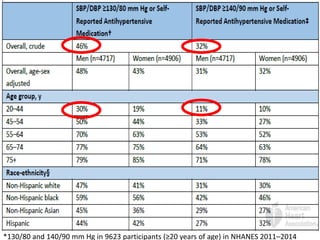

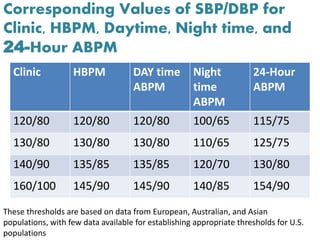

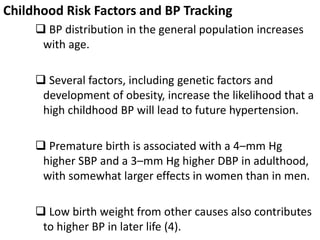

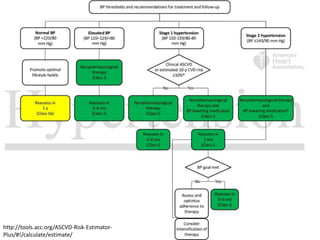

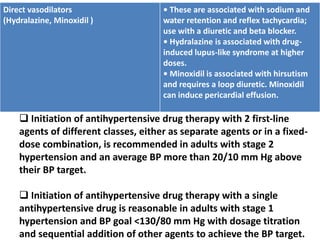

- The new guidelines lower the threshold for stage 1 hypertension to 130/80 mm Hg from 140/90 mm Hg. This means nearly half of US adults now have hypertension based on these guidelines.

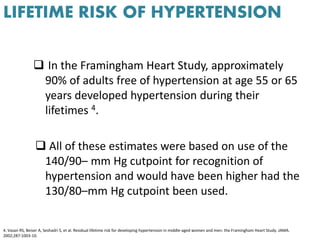

- Lifetime risk of developing hypertension is approximately 90% for adults aged 55-65 based on data from the Framingham Heart Study.

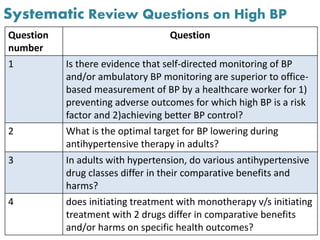

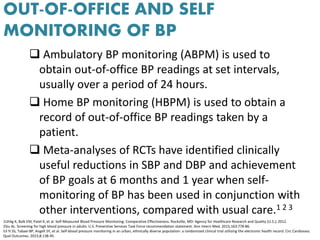

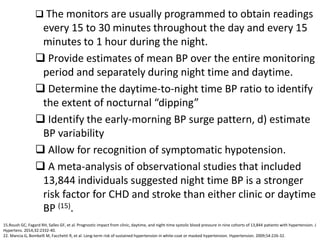

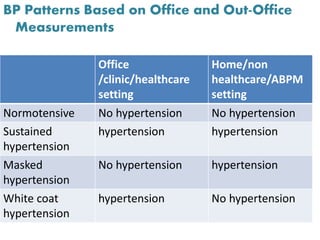

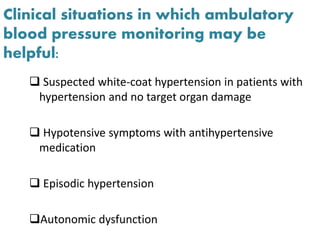

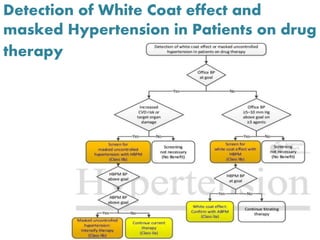

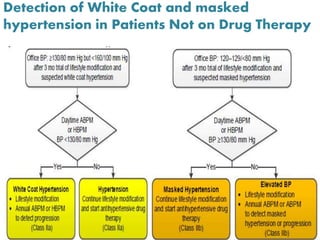

- Self-monitoring and ambulatory blood pressure monitoring provide benefits over office-based measurements alone for managing hypertension.

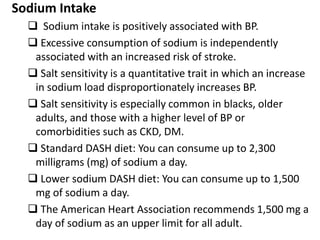

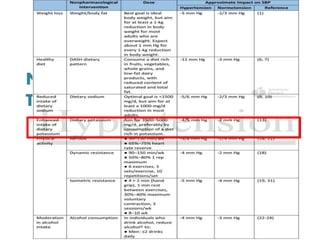

- Lifestyle modifications such as weight loss, reduced sodium intake, increased potassium and physical activity are recommended as first-line treatment for many with elevated blood pressure

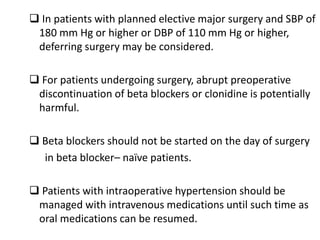

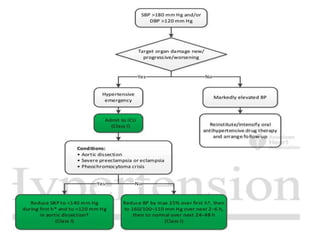

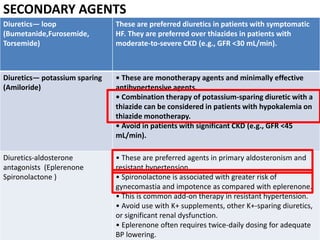

![10. Aortic Disease

Beta blockers are recommended as the preferred

antihypertensive agents in patients with

hypertension and thoracic aortic disease (1, 2)

1. Genoni M, Paul M, Jenni R, et al. Chronic beta-blocker therapy improves outcome and reduces treatment costs in chronic

type B aortic dissection. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2001;19:606-10.

2. Suzuki T, Isselbacher EM, Nienaber CA, et al. Type-selective benefits of medications in treatment of acute aortic

dissection (from the International Registry of Acute Aortic Dissection [IRAD]). Am J Cardiol. 2012;109:122-7.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/hypertensionredefined-180819191329/85/Hypertension-redefined-70-320.jpg)