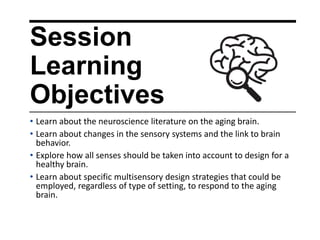

The document provides information about a session on neuroarchitecture and aging. It begins with welcome and CE information. It then describes how the aging brain undergoes changes that impact sensory perception and cognitive function. As people age, their senses of hearing, vision, smell, taste and touch decline. The session will discuss research on the aging brain and senses, and explore design strategies that can address sensory changes and support brain health for older adults. These include addressing visual challenges through lighting, color contrast and glare reduction, as well as fall prevention through clear wayfinding and safe circulation.