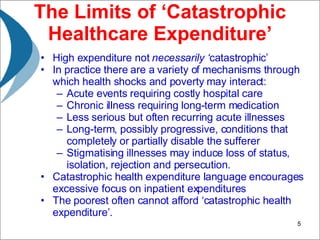

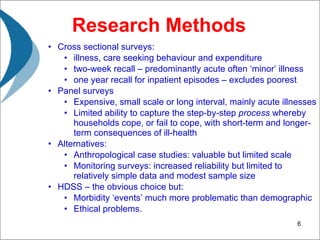

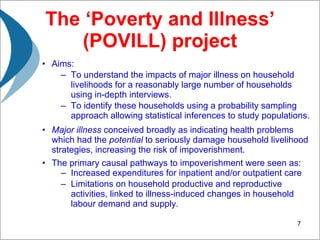

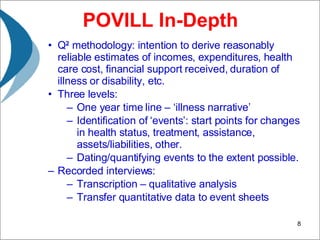

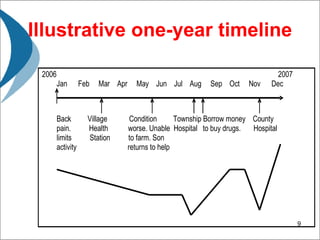

This document discusses measuring the linkages between health and livelihoods in order to design effective interventions. It notes that serious illness can greatly impact individuals, households, and families through reduced income, increased healthcare costs, and selling of assets. However, the impacts are complex as health problems vary in severity and duration. The document also examines different research methods and their limitations in fully capturing how households cope with health issues over time. It then describes the "Poverty and Illness" project which aims to better understand the livelihood impacts of major illnesses through in-depth interviews with households selected via probability sampling.