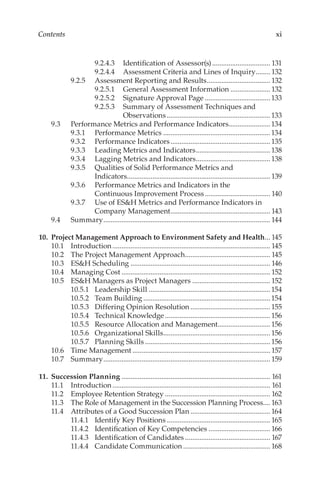

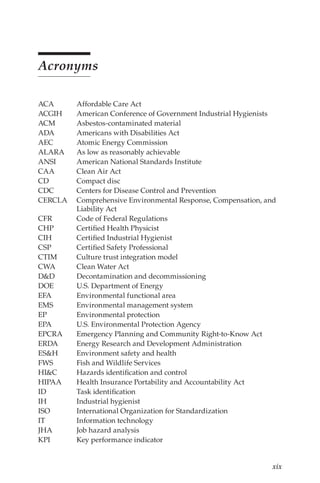

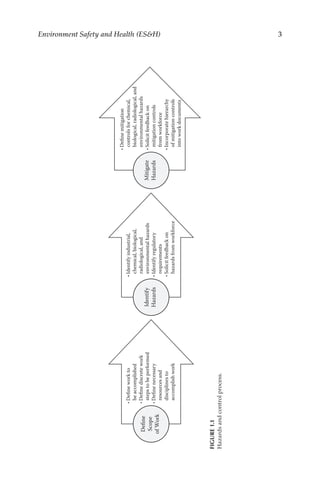

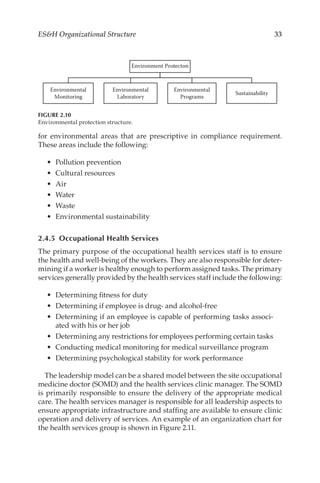

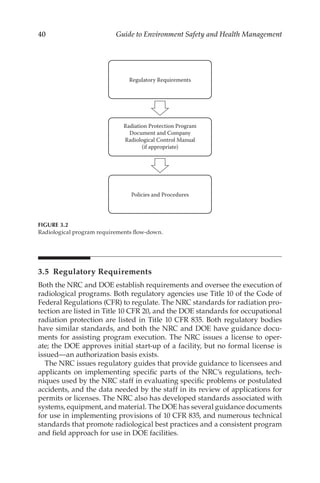

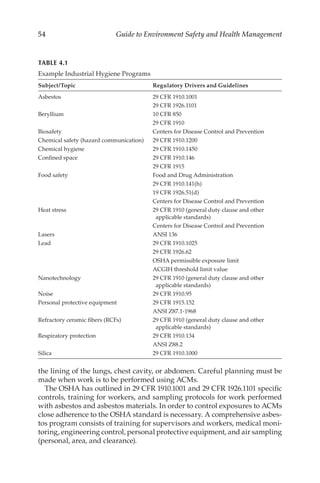

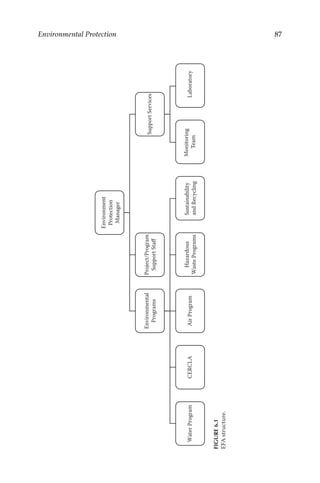

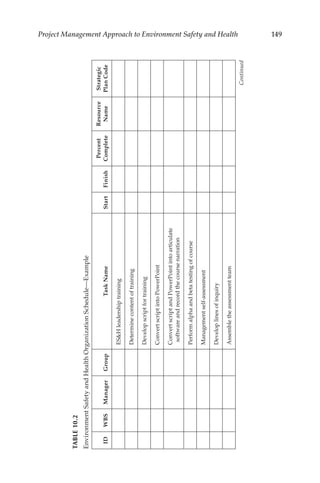

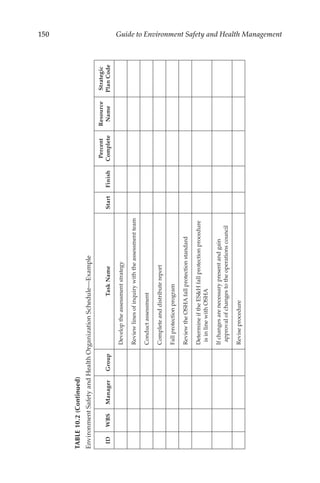

This document provides guidance on developing, implementing, and maintaining an effective environment, safety, and health (ES&H) management program. It discusses identifying hazards, applying ES&H principles to design, operations and maintenance, and using a work control process. The document also outlines key aspects of an ES&H organizational structure including roles for radiation safety, worker safety and health, occupational health, and environmental protection. Maintaining an effective ES&H program requires training, compliance, and addressing issues as they arise through communication and feedback.