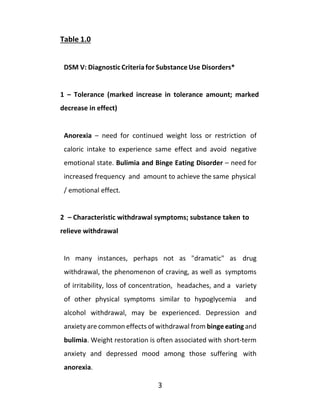

The document discusses evidence that eating disorders can be considered addictions based on criteria for substance dependency from the DSM-V and APA. It notes many similarities between the symptoms of eating disorders and the seven criteria for substance dependency/addiction. The document also discusses research showing deficits in dopamine levels and receptors in the brains of those with eating disorders and addictions, suggesting underlying biological similarities.

![The second section begins to explore the commonality of eating

disorders and attempts to debunk the belief eating disorders

represent separate and different disease entities. The common

thread existing among the various flavors of eating disorders is

reviewed and the trap of focusing on weight, appearance, and

dieting is exposed. Setting the stage for treatment thus begins with

defining the problem.

The third section begins to look at the recovery process at

Milestones. By distilling the basic elements of long-term recovery,

participants in the program learn about, and most importantly

practice, a set of skills that virtually guarantees freedom from

addictive relationships with their eating disorder. In doing so, “one

day at a time” the physical, emotional, and spiritual symptoms

inherent with an addiction begin to change course and recovery

follows.

The fourth section focuses on maintaining your recovery and how

S.E.R.F (Spirituality, Exercise, Rest and Food Plan) can assistyou.

The fifth section of this book is devoted to continuing care and the

role of support groups such as OA [Overeaters Anonymous],

Anorexics and Bulimics Anonymous [ABA], Alcoholics Anonymous

[AA], Narcotics Anonymous [NA], etc. can help you maintain your

recovery.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2d2e1552-de6e-4bdc-ab82-97110fc0cf25-160917112325/85/GUIDE-TO-ED-RECOVERY-2016-5-320.jpg)

![2

“Addiction is a primary, chronic disease of brain reward,

motivation, memory and related circuitry. Dysfunction in these

circuits leads to characteristic biological, psychological, social and

spiritual manifestations. This is reflected in the individual pursuing

reward and/or relief by substance use and other behaviors. The

addiction is characterized by impairment in behavioral control,

craving, inability to consistently abstain, and diminished

recognition of significant problems with one’s behaviors and

interpersonal relationships. Like other chronic diseases, addiction

involves cycles of relapse and remission. Without treatment or

engagement in recovery activities, addiction is progressive and can

result in disability or premature death.” *American Society of

Addiction Medicine, 2012

To see if “the shoe fits”, you might take the quote above and simply

insert the phrase eating disorders in lieu of the word addiction.

Likewise, the words restricting, purging, binge eating, and so forth

could be inserted. In my professional experience, the shoe fits

quite well. It may be time to look at an eating disorder with respect

to its’ real nature rather than surface appearances. The

implications for treatment and long-term recovery areprofound.

Let’s take a moment and review the seven criteria the APA lists as

symptomatic of dependency [aka addiction]. I’ve added a few

comments for each criterion relating it to an eating disorder.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2d2e1552-de6e-4bdc-ab82-97110fc0cf25-160917112325/85/GUIDE-TO-ED-RECOVERY-2016-14-320.jpg)

![5

6– Social, occupational or recreational activities given up or

reduced

Common to all eating disorders – social isolation, as well

as, diminished activities that interfere with eating disordered

patterns.

7 – Use continues despite knowledge of adverse

consequences (e.g., failure to fulfill role obligations, uses when

potentiallyphysicallyhazardous)

Common to all eating disorders – continued eating

disordered behaviors, despite physical, emotional, social, o r

financial consequences.

*DSM IV R- American Psychiatric Association/American Society of

AddictionMedicine

*Meeting a minimum of three criteria is sufficient for a diagnosis

of substance dependency [DSM IV-R]. DSM V-now defines a

substance use disorder with three subtypes: mild, moderate, or

severe. See: DSM V SUBSTANCE USECRITERIA

In recent years the addiction model, at least as it applies to bulimia,

binge eating, and anorexia has been the subject of an expansive](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2d2e1552-de6e-4bdc-ab82-97110fc0cf25-160917112325/85/GUIDE-TO-ED-RECOVERY-2016-17-320.jpg)

![6

body of research. A terrific summary of this appears in the newly

published text “Food and Addiction” edited by Kelly Brownell and

Mark Gold, Oxford University Press, 2012. The concentration of

this effort has ranged from an exploration of the nature of certain

properties of [mostly refined] foods to the neurobiology and

physiology of [eating disorders] addiction. There appears to be an

interaction between the nature of the substance [addicting or non-

addicting] and the nature of the person [addict or non-addict].

Hence, it is difficult to pin the blame only on the substance without

consideration of the person. For example, morphine is quite

addictive but not all patients receiving this drug to control pain

become “addicts.” Still others, who have a history of addiction, are

more vulnerable to becoming dependent on the drug. We know

today sugar and its’ many derivatives is addicting as a substance.

However, addiction to sugar is both dose and length of exposure

dependent, as well as, being influenced by the person consuming

it. This is to say it takes “two to tango” - with the substance needing

to interact with a predisposed and willingsubject.

The most compelling evidence to date seems to have come to light

with the brain mapping capabilities of modern radiographic

imaging (PET Scan/brain imaging). Sparing the reader the technical

side of this, researchers have been able to locate and display areas

of the brain reacting to substances and stimuli in ways that

differentiate the addict from the non-addict. Furthermore, we now](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2d2e1552-de6e-4bdc-ab82-97110fc0cf25-160917112325/85/GUIDE-TO-ED-RECOVERY-2016-18-320.jpg)

![7

better understand the “reward system” in the brain. We can clearly

see differences between dependent and non-dependent subjects.

Dopamine has been shown to be a primary “feel good” chemical in

the brain. Researchers have uncovered a stunning similarity

between chronic cocaine and stimulant abusers, and compulsive

eaters and bulimics – namely all have shown deficits in dopamine

concentrations and dopamine receptors on their PET scans. The

control subjects [non-addicts] did not display the same deficits. In

yet another study, the two groups were exposed to just pictures of

cocaine or, for overeaters, highly palatable desserts. The visual

cues alone caused a marked increase in dopamine activity among

the cocaine and ED subjects, but not so with their non-addict

peers. So, both an external cue [visual], as well as, the actual

consumption of the substance can elicit changes in brain

chemistry. This is what behaviorists call classical conditioning.

I’ve included an article I wrote summarizing the chemistry involved

with many eating disorders. The focus of the article looks at the

role of one of the basic neurotransmitters we spoke about –

dopamine. As mentioned, dopamine has been studied with respect

to its role in addiction. The progression from use, to abuse, to

dependency likely involves the interplay of amount, duration, and

individual predisposition – whether we speak of a drug or an eating

disorder.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2d2e1552-de6e-4bdc-ab82-97110fc0cf25-160917112325/85/GUIDE-TO-ED-RECOVERY-2016-19-320.jpg)

![8

Dopamine- the “Feel Good Brain Chemical”*

In an article on the role of dopamine and dopamine receptors from

a March 2010 edition of "Neuroscience" - a well-known and

respected professional journal, the researchers found a significant

difference between laboratory animals that were "over-fed" and

exposed to unlimited amounts of sugar laden and highly processed

[junk] foods versus controls fed regular rat chow. Indeed, the junk

food rats developed an "addiction-like reward deficit" with

dopamine concentrations. The virtual destruction of D2dopamine

receptors in the brain accounts for this.

Translation - over time, when overeating highly "palatable" foods

(e.g. sugar, high fat) they [rats] developed deficits in their ability to

properly assimilate the neurotransmitter dopamine. Deficits in

dopamine are seen with cocaine addicts when they are "crashing"

and withdrawing from cocaine - they become depressed and their

appetite becomes almost insatiable. Likewise, the deficit in

dopamine for binge eaters and bulimics tends to increase over

time with the result being a biological (addictive) propensity to

repeat episodes of disordered eating with greater frequency. Of

course we’ve come to know this phenomenon as tolerance. For the

bulimic, the misguided attempt to deal with this is purging or

alternating between periods of binge eating and restricting, for the

compulsive overeater, controlling this addictive cycle gives way to](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2d2e1552-de6e-4bdc-ab82-97110fc0cf25-160917112325/85/GUIDE-TO-ED-RECOVERY-2016-20-320.jpg)

![9

another "diet". Whether this mechanism plays a role with forms of

anorexia is still a subject for speculation. I suspect the addictive

process with restricting is similar.

Much like the cocaine user who becomes an abuser and then an

addict, neurotransmitters (dopamine receptors) are eventually

destroyed. The only relief is...more cocaine for the fewer receptors

available. The phenomenon of tolerance takes hold and theaddict

needs more of the substance to achieve the desired effect until no

matter how much substance is available it no longer works as it did

in the beginning stages. In fact, in most end stage addictions the

best one can hope for is to postpone withdrawal symptoms.

Addiction thus becomes a full-time career.

The "food addict" may begin abusing food and develops a similar

"tolerance" to refined carbohydrates (sugar, flour) or greater

volumes of food and, likewise, alters the brain's (reward) structure

(dopamine receptors) and the physical addiction to overeating

takes hold. A similar mechanism exists with purging, as applied to

endorphin metabolism. With anorexia the starvation process

creates a sort of tolerance as the body fights to survive and the

anorexic must restrict more and more to maintain the sameeffect

[e.g. avoid weight gain and control despair and anxiety]. Thereare

a few studies to suggest the stress hormone cortisol plays a rolein

this process much like the neurotransmitters in the brain.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2d2e1552-de6e-4bdc-ab82-97110fc0cf25-160917112325/85/GUIDE-TO-ED-RECOVERY-2016-21-320.jpg)

![11

As with cocaine addicts, it's likely that over any extended period of

time, the mechanisms responsible for manufacturing and making

available dopamine at normal levels will re-emerge... provided the

"addict" adheres to a prescribed course of treatment (e.g. abstains

from the offending substance - cocaine or, for the food addict, the

combination of high-glycemic foods and over feeding [exorbitant

volume]. Likewise, proper nutrition and restoration of a

reasonable BMI would likely have a similar effect for the restricting

forms of eating disorders.

The first step in recovery is recognizing the importance of

abstaining from the offending substance[s] and behavior[s]. Those

with an eating disorder may need to consider a food plan that does

not evoke a physical craving. The current body of research suggests

the more highly processed a food substance is the more likely it is

to heighten the potential for abuse and dependency. The

exponential increase with childhood obesity and early onset

diabetes is directly related to this phenomenon. The evidence has

become overwhelming.

References:

Marty Lerner, PhD .2012

http://www.selfgrowth.com/experts/marty-lerner-phd

Laboratory of Behavioral and Molecular Neuroscience, Dept. of

Molecular Therapeutics

- Published 3/2010 in Nature Neurosciences

Neuroanatomy of Addiction, George Koob, 2012 in Food and

Addiction by Brownell and Gold, Oxford Press, 2012](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2d2e1552-de6e-4bdc-ab82-97110fc0cf25-160917112325/85/GUIDE-TO-ED-RECOVERY-2016-22-320.jpg)

![13

related to alterations of interceptive awareness. There may be

some disregulation of insula function. This may, in part, explain

why a recovering anorexic can draw a self-portrait of their body

image that is typically 3 times its actual size.” To quote from

someone with this experience who is now recovering, “I was down

to 80 pounds at five-foot six,” she says. “My self-portrait was so

distorted I was able to lie down inside the drawing, but that’s how

I saw myself."

A reprint from an article published in Bloomberg News serves as

an excellent summary of the evidence pertaining to the addictive

nature of highly processed [junk] foods. Written by investigative

journalists Robert Langreth and Duane Stanford, the article

explores the social, economic, and biological impact of food

addiction and provides a rather convincing indictment of the

companies profiting from these products. Here is a [reprint] of the

Bloomberg article

The Case for Commercial FoodAddiction

REPRINT- Bloomberg News, April 2011

Robert Langreth and Duane Stanford, investigativereporters

A growing body of medical research at leading universities and

government laboratories suggests that processed foods and sugary](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2d2e1552-de6e-4bdc-ab82-97110fc0cf25-160917112325/85/GUIDE-TO-ED-RECOVERY-2016-25-320.jpg)

![29

Defining the Problem…

Ok, let’s take a moment and “think outside the box” and ask what

all these different “flavors” of disordered eating have in common

rather than what separates them? Is it not true most people,even

medical and mental health professionals, tend to identify and

define an eating disorder in terms of how someone looks or how

overweight or underweight they appear? After all, how can one

suffer with an eating disorder if they don’t appear eating

disordered? And, how is it possible someone can admit to having

an issue with abusing food, excessive dieting, or compulsive

exercising, and not show outward signs?

Even more striking is this perception is too often supported by

many of the treatment programs and self-help groups intendedto

help people find their way into recovery. In effect, this seems to

overshadow the fact that, recovery is about more than just

changing someone’s weight or eating behavior. For most people

with a bona fide eating disorder, body weight and body image

perception are a set of symptoms and [excuse the pun] not the

whole enchilada. Fact is, not all underweight people suffer with

anorexia and not all overweight people suffer with a binge eating

disorder. Suffice it to say there may be a difference between a

weight disorder and an eating disorder. Again, I refer the reader to](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2d2e1552-de6e-4bdc-ab82-97110fc0cf25-160917112325/85/GUIDE-TO-ED-RECOVERY-2016-41-320.jpg)

![31

the APA guidelines [criteria] for dependency to delineatebetween

a weight problem and an eating disorder. (See ChapterOne)

It would seem many people who do not have first-hand experience

of an eating disorder “miss the boat” in this respect. Truth be told,

this is similar to what most people once believed about alcoholism

and drug addiction: alcoholics all wear sneakers, trench coats,and

live under bridges, while all drug addicts live on the streets and

steal money for drugs, and so on. We know differently today. The

overwhelming majority of chemically dependent people cannot be

“picked out of a crowd.” That said, I’d suggest we revisit the

stereotypes many of us have with respect to eating disorders.

This leads us to a retooling of the defining characteristics of all

eating disorders and an assumption I would present to the reader

for consideration.

Eating Disorders are best defined by the degree the relationship

with food and/or body image diminishes the quality of

someone’s life.

A helpful suggestion for newer members of 12-Step programs is to

“identify and not compare.” The reasoning behind this suggestion

is to not provoke the newcomer into a form of denial by telling

themselves something along the lines of “I’m really not as bad as”](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2d2e1552-de6e-4bdc-ab82-97110fc0cf25-160917112325/85/GUIDE-TO-ED-RECOVERY-2016-42-320.jpg)

![32

another member. The effect of one person’s experiences shared

with a fellow having the same experiences is, to quote a related

program, “unparalleled.” Once the initial layer of the onion is

peeled, namely the “what makes me different than these people,”

the stage is set for identification rather than comparison. The

question then becomes, “so what do I have in common with

everyone here?” From that point forward, the focus begins to

center more on the solution – “what do I need to do to recover?”

Doing otherwise leaves someone with over analyzing the problem

and little energy left to begin work on the solution.

*OvereatersAnonymous[http://www.oa.org]

*AnorexicsandBulimicsAnonymous[http://aba12steps.org/]

Aside from meeting at least three of the criteria for dependency

we read about in the previous section, eating disorders tend to

have in common the relentless attempt to control how we feel.

Although we’ll look at this more in depth in the next section, I

would suggest that all eating disorders are motivated by an intense

desire to fix or avoid an unpleasant feeling. Although the feeling

may vary within and among persons, the end game remains the

same – control, fix, and change the feeling / discomfort du jour.

One variant on this theme comes from a summary statement made

by a very famous psychoanalyst, Carl Jung. Although I may be](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2d2e1552-de6e-4bdc-ab82-97110fc0cf25-160917112325/85/GUIDE-TO-ED-RECOVERY-2016-44-320.jpg)

![34

Over time, too much avoidance and distraction have the potential

of becoming addictive, as our tolerance for discomfort becomes

less and less and our need to find relief grows stronger. Unless we

find a more appropriate and less destructive means of reacting to

“legitimate suffering” we are prone to creating a number of

compulsive and addictive behaviors.

Although I would hardly count myself in the same category as Carl

Jung, I do believe he was on to something back in his day. After all,

people do not starve themselves, make themselves sick, take

handfuls of laxatives, binge eat until they’re in pain, exercise to the

point of exhaustion, or engage in any number of painful actions

unless they are attempting to avoid or change their emotional

state. As mentioned, what we see with eating disorders is a

progression of first attempting to feel better followed by an

attempt to delay or avoid feeling bad [withdrawal] in the later

stages. I’ve seen this to be as true for someone in the midst of

anorexia as someone struggling with a binge eating disorder. The

same can be said for almost alladdictions.

Another similarity within the ED population has to do with the

incidence of coexisting mood disorders. More often than not

recurring depression, anxiety, and marked mood swings come with

the territory. In addition, more than half the people seeking

treatment have histories of abusing alcohol, drugs, and/or other](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2d2e1552-de6e-4bdc-ab82-97110fc0cf25-160917112325/85/GUIDE-TO-ED-RECOVERY-2016-46-320.jpg)

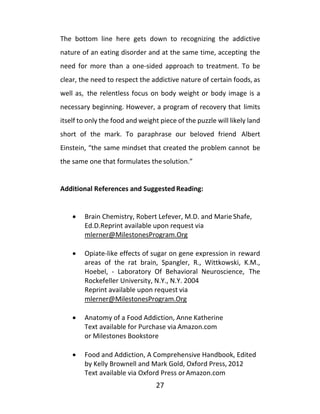

![35

forms of self-abusive behaviors like cutting. Regardless of the

particular eating disorder, it’s rare to see someone with an ED

without an accompanying mood disorder, chemical dependency,

or self-abuse issue.

Table 2.1

Similarities among the EatingDisorders

- The majority of people with an ED meet the established

criteria for [addiction] dependency per the same criteria

typically reserved for substance dependencies*.

- ED behaviors are initiated in an attempt to avoid or change

uncomfortable feelings - usually negative feelings and

emotional states.

- Most eating disorders typically are associated with a mood

disorder that often pre-dates the beginning of the eating

disorder.

- Regardless of ED type, at least half the people coming to

treatment for an ED also have abused alcohol, drugs, or

relied on additional forms of self-medication.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2d2e1552-de6e-4bdc-ab82-97110fc0cf25-160917112325/85/GUIDE-TO-ED-RECOVERY-2016-47-320.jpg)

![36

- Having an ED makes someone vulnerable to “switching

addictions” throughout the life cycle of their ED.

- Independent of the form of ED, control issues are a central

theme needing to be addressed – first with food and

weight, and later with other areas of daily living such as

relationships.

- With the exception of some subtypes of anorexia, most

people suffering with an eating disorder react to certain

foods [e.g. sugar derivatives, refined flours, highly

processed junk foods, etc.] differently than their non-

eating disordered peers. *see D2 receptors and eating

disorders

- Both psychological and physiological factors are inherent

among all forms of eating disorders. Physical dependency

and psychological dependency interact to create an

addictive relationship with food, body weight, and/or

dieting.

- Long-term recovery from an eating disorder requires

significantly more than a temporary change in someone’s

body mass index [BMI / weight / appearance] and eating

pattern.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2d2e1552-de6e-4bdc-ab82-97110fc0cf25-160917112325/85/GUIDE-TO-ED-RECOVERY-2016-48-320.jpg)

![37

- Recovery often requires the ongoing participation in a

support group or a continuing care plan after formal

treatment ends.

- Appropriate [non-habit forming] medication[s] usually are

needed to treat co-occurring depression or a similar issue

accompanying an eating disorder. In many instances, the

mood disorder is a “stand alone” diagnosis that exists with

or without the ED.

- Most people with an eating disorder have some level of

impairment with an ability to differentiate between

hunger [physical needs] and appetite [psychologically

driven]. – internal versus external cues of hunger

- As with other addictions, remission is a more realistic

expectation with treatment outcome rather than a “cure.”

In effect, addiction is a life-long disease that can be

arrested by remaining engaged in consistent recovery

related activities. Remission can be life-long or short-term.

Co-Existing Addictions and RelatedProblems

Those of us who have been in and around the recovering

community are quite aware of the prevalence of eating disorders

within the fellowships of Alcoholics Anonymous, Narcotics](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2d2e1552-de6e-4bdc-ab82-97110fc0cf25-160917112325/85/GUIDE-TO-ED-RECOVERY-2016-49-320.jpg)

![43

Cross Addiction and Co-Existing Issues

The take away from this topic is simply to recognize addictions and

compulsions are often misguided attempts to manage or control

our feelings. That being the case, it would seem likely when we

stop using one means of doing this we’re prone to “go back to the

well” and rely on another. The important thing here is to accept

the need to work on the problem [nature of the person] and not

just the symptom [the addiction]. Be patient, be cautious, and be

honest with yourself. Some of these issues can be tackled along

with your eating disorder treatment and some will be taken on

later in the course of your recovery. Which one and when will

depend on how they threaten your eating disorder recovery and

whether you can “buy time” to work on them at a later date.

Body Image and Body Dysmorphic Disorder

I’ve always been fascinated by the “disconnect” between how we

experience our speaking voice and how it sounds when we listen

to it from a recorded device. Likewise, there’s the tendency to view

different photographs of ourselves and wonder how we could look

so different in each one, yet almost everyone else hardly notices

any change. How can we see the same picture so differently from

others? Is it possible our perception is influenced by factors we’re

not totally aware of? To be clear, this phenomenon of perceiving

and experiencing ourselves differently from the “outside world” is](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2d2e1552-de6e-4bdc-ab82-97110fc0cf25-160917112325/85/GUIDE-TO-ED-RECOVERY-2016-55-320.jpg)

![46

of ourselves. The “smoke and mirrors” effect of an eatingdisorder

then goes something like this: “I look in the mirror and I see myself

as and that’s what really makes me feel depressed. If I were

able to change the way I look then I wouldn’t be so depressed.”

Hence the anti-depression fix becomes changing the body or

numbing the pain with further restricting or binge eating, etc. The

angst of how we experience our body is believed to be the problem

and the solution becomes changing the body at any cost – evento

the point of engaging in life threatening behaviors.

I’m not proposing the solution to a body image issue is simply

“buying into” this theory or finding the right “medication.” What I

would suggest is at a minimum conceding your “perception” is a

confused one and giving consideration to putting your energyinto

a recovery process. That process would give equal time to

following a treatment plan that includes a healthy food plan,

abstaining from your eating disorder behavior[s], with professional

help if necessary, and also finding a way to appropriately manage

your depression. Last, but not least, I would be remiss not to

mention that more than half of the people we see at Milestones

also have relied upon alcohol, drugs, or other compulsions in

addition to their ED in a misguided attempt to “control” their

depression and perceptions.

In sum, body image disturbances are a prominent feature of most

eating disorders. Whether they are a symptom of an underlying](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2d2e1552-de6e-4bdc-ab82-97110fc0cf25-160917112325/85/GUIDE-TO-ED-RECOVERY-2016-58-320.jpg)

![47

issue with a mood disorder such as depression or generalized

anxiety disorders, a manifestation of past trauma, or any number

of factors often associated with eating disorders may not be

important. What matters is the need to acknowledge body image

disturbance as a symptom of the disease – more so for some, and

less so for others. Another point to consider is resolving the

depression or underlying mood disorder does not guarantee the

resolution of a distorted or negative body image. That said feelings,

thoughts, and perceptions about our body become less

troublesome over time if following a recovery program. By

incorporating the principles of a 12-Step program and some ofthe

principles discussed, we can learn to live with our imperfections.

The frequency and intensity of negative experiences with our body

will diminish. Self-focus and a renewed interest in other people

and things beside ourselves will usually follow.

Internal and External Cues: What also makes usdifferent?

My experience has been eating disorders almost uniformly involve

a broken thermostat-like mechanism that governs internal cues

[symptoms] of hunger and fullness. In other words, unlike our

“normal eating” contemporaries, we are often confused when to

eat, what to eat, how much to eat, and/ or when to stop eating.

Whether suffering with anorexia, bulimia, or compulsive

overeating, there is a tendency to be more governed by external

stimuli - such as the sight of food, smells, time of day, stressful](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2d2e1552-de6e-4bdc-ab82-97110fc0cf25-160917112325/85/GUIDE-TO-ED-RECOVERY-2016-59-320.jpg)

![52

to as a cucumber becoming a pickle never to return to being a

cucumber again. Being a pickle, however, does have its

advantages. With acceptance of our reality, the adoption of a

reasonable food plan becomes a preferred place to be ratherthan

a prison sentence. *Clean eating, along with the other components

accompanying a recovery lifestyle become a matter of preference

and not something we do because “we have to.” You’ll find the

same experiences among people enjoying long-term recovery

from alcohol, drugs, and other dependencies - namely their

“recovery” has become a blessing and not a curse. I’d further the

analogy to someone with any chronic disease. If we we’re

discussing diabetes treatment then eating within the bounds of a

healthy whole-food plan, moderate exercise, managing stress, and

developing a personal sense of spirituality would be the exact

prescribed program called for. If you think about it, this formula

would serve anyone with a chronic disease and go a long way to

restoring someone’s health and quality of living.

[*]It’s important to remind the reader our reference to “abstinent

food plans” and “clean eating” are about healthy and adequate

nutrition and not in the service of further restrictingcalories.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2d2e1552-de6e-4bdc-ab82-97110fc0cf25-160917112325/85/GUIDE-TO-ED-RECOVERY-2016-64-320.jpg)

![55

no cigar. Eventually you might get it to close with one or two eggs

left. Not much recovery left here. Maybe your SERF is reduced

to EF.

And now…. Take an identical size bowl that’s empty and place it

next to the original one. Now take all four [SERF] eggs and place

them in the empty bowl FIRST. Now pour the same rice from the

original bowl over the eggs on the bottom. And, finally, place the

lid on the bowl. Guess what – it fits.

Believe it or not, this is something we actually do as a

demonstration from time to time at Milestones. In reality, we’ll

find ourselves with more than enough time to take care of what

needs doing when we put our recovery first and allow the rest of

our daily stuff to fall into place. Being consistent with the SERF

basics is one of the paradoxes of recovery – namely putting

ourselves first-positions us to better take care of everything else.

As has been mentioned repeatedly throughout this guide Doing is

Believing.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2d2e1552-de6e-4bdc-ab82-97110fc0cf25-160917112325/85/GUIDE-TO-ED-RECOVERY-2016-67-320.jpg)

![57

The Roadmap

When all else fails, follow the directions” – anonymous

Ok, now we’ve come to the instructions. You know, the written

materials [aka instructions] most people either discard or only

glance at while putting together whatever it is they’re trying to put

together. If you’re like me, you usually end up with a bunch of parts

left over and something that doesn’t quite look like the picture on

the box. This may be a time to do it differently. A word of caution

- it’s not unheard of for people with, shall we say, control issues,

to be slightly defiant and a tad bit stubborn [a little sarcasmhere].

If this doesn’t apply to you then I would suggest you may be inthe

wrong place or, more likely, are having one hellacious issue with

denial. Fact is, most people who suffer with an eating disorder,

have more issues with control and trust [what a surprise] than their

non-addict peers. These two issues are a central theme of what

needs to be addressed in the recovery process. We’ll talk about

control and trust in a few pages.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2d2e1552-de6e-4bdc-ab82-97110fc0cf25-160917112325/85/GUIDE-TO-ED-RECOVERY-2016-69-320.jpg)

![63

sustainable lifestyle. Many refer to this as a

recovery lifestyle. The program follows a

"blended" approach to treatment - addressing

both the addictive and emotional aspects of an

eating disorder. Residents attend a fullschedule

of group and individual activities during the day,

as well as, participate in various support groups

during evenings and weekends. Grocery

shopping, meal preparation, and "real world"

experiences are an integral part of the

program.” [*]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2d2e1552-de6e-4bdc-ab82-97110fc0cf25-160917112325/85/GUIDE-TO-ED-RECOVERY-2016-75-320.jpg)

![68

At first glance these concepts may seem simple enough. However,

there is more to this stuff than meets the eye. There seems to be

an implied assumption in the world of mental health treatment

that goes something like this: if we can change how someone feels,

or if we can change what thoughts they have, then we can get

someone to change what they’re doing. I suspect most of us hold

onto the belief that goes something like this - if a therapist or

someone I looked to for help could fix how I feel, then maybe I

would be able to _. You fill in the blank. Try this one on for

size: “If or when you can help me feel better about my body I will

buy shorts and exercise.” “When I don’t feel so big I’ll let myself

eat.” "When I’m not so nervous, I’ll speak in front of the class and

be able to do the presentation.” “When I get [aka feel] motivated,

I’ll study.” No doubt we can make an endless list of “when I feel, I

will.” Experience has shown repeatedly when we put a “state of

mind” as a condition for doing something we’re likely to be stuck

in the problem. Conversely, when we develop the discipline of

doing what needs doing despite the feelings or intrusive thoughts

we are moving toward the solution. Let’s take a few minutes and

look at the basic principles of this philosophy and explore it. I’ve

taken the liberty of paraphrasing some of the CL principles David

Reynolds talks about in his text. They are:](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2d2e1552-de6e-4bdc-ab82-97110fc0cf25-160917112325/85/GUIDE-TO-ED-RECOVERY-2016-80-320.jpg)

![69

- Feelings are not directly controllable by self will

- Feelings need to be recognized and accepted “as is”

- Every feeling, no matter how unpleasant, has a

purpose

- Feelings fade over time, unless re-stimulated

- Feelings [and thoughts] can be indirectly

influenced by behavior

- We are responsible for what we do no matterhow

we feel

If you really consider these, they tend to appeal to our common

sense and really don’t require a degree in rocket science. However,

taking a more detailed view and truly contemplating these you’ll

notice a much more profound meaning. What is being proposed

are a set of what could be called, universal truths about the human

mind and how it operates. It suggests trying to control our feelings

by directing energy into simply “willing” ourselves to feel

something is a wasted exercise. Try sitting down in a chair when

you’re feeling sad and “will” yourself to feel happy for any

extended period of time. Try willing yourself to fall in love with

someone you’re not in love with. Likewise, controlling your

thoughts by imposing self-will is quite limited as well. Ever tell](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2d2e1552-de6e-4bdc-ab82-97110fc0cf25-160917112325/85/GUIDE-TO-ED-RECOVERY-2016-81-320.jpg)

![71

yourself not to think about something? I usually end up obsessing

about something the more I try or am told not think about it. The

“magic sauce” in all this is that our thoughts and emotions can be

indirectly influenced by what we do. In other words, what we do

has the greatest [probable] impact on what we think and feel over

time. The cart is placed before the horse when we get it backwards

by insisting we fix our feelings first. Believing our feelings and

thoughts must be changed before we’re able to change our

behavior can be a very costly mistake.

Once again, eating disorders and addictions are about fixing

feelings. Now we can add another idea, this time regarding the

solution – “recovery is about transcending our need to fix how we

feel and doing the next right thing no matter what we’re feeling.”

This challenges the belief that controlling our feelings and thoughts

is the primary goal of psychotherapy. Instead we’re proposing the

reverse - controlling our actions and letting the feelings and

thoughts take care of themselves. “Doing is believing” as I like to

say.

Feelings and thoughts, as we’re reminded, are never constant.

Much like weather patterns, our emotions and thoughts are always

changing. They come and go. In this sense, nothing stays the same.

Trying to exert control over these is like trying to control the

weather – not possible. Behavior, with very few exceptions is](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2d2e1552-de6e-4bdc-ab82-97110fc0cf25-160917112325/85/GUIDE-TO-ED-RECOVERY-2016-82-320.jpg)

![73

The dateline is eighth grade at Lawrence Junior High School

somewhere in New York. I am about 14 years old and suffer with

what was, at the time, referred to as juvenile onset obesity. In

other words I was a compulsive eater who was twice the size of

what would be considered “normal” for a 14 year old. So nowinto

the classroom enters Paula Goldberg, a very “hot” looking 14 year

old dressed in a mini skirt and knee high boots. No doubt you get

the picture. Kind of like the scene from the “Go Daddy.Com”

commercial with the supermodel and computer geek in a lip lock.

Fast forward the movie and I began a “diet” of raisins, cottage

cheese, and diet soda for the next several months until I became

this rather good looking, “svelte,” high school freshman. Now,

eventually, I ask Paula out to the junior, then senior prom.

Throughout high school we were, as they say, an item.

Comes time for high school graduation and off to college. Now

we’re both about to go to different colleges. I figure it’s time for

me to “sow some wild seeds” and not limit myself to Paula. I figure

it’s time to break up with her. Here’s where it gets a little

interesting. I invite her to meet me at the Town Diner [remember

Harry, this is the same place].

So we sit down at the table and Paula says she wants to tell me

something. I tell her “I have something to tell you too Paula, [big

mistake here] but instead I tell her “you go first Paula.” Paula

proceeds to tell me “Marty, you know I care about you, but I think](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2d2e1552-de6e-4bdc-ab82-97110fc0cf25-160917112325/85/GUIDE-TO-ED-RECOVERY-2016-85-320.jpg)

![81

need to do recovery.” By doing so, your perceptions and thoughts

are likely to be reshaped and indirectly influenced by your actions.

You can again accuse me of butchering another famous quote by

restating it as follows: “I think I am, therefore I am” might be better

stated as “I do, therefore I am” – from that perspective, we tend

to be defined by what we do and not so much by what we say or

feel. Another cliché popular within recovery circles is “we are

judged not so much by our intentions as by our actions.” I know

very few people who get in trouble for what they think or feel, but

plenty who get into issues for what they do. Conversely, proper

action can produce amazingly good results in spite of feeling and

thinking negatively. More than likely the negativity will change

over time if the behavior is positive.

Being realistic about this “just do it” discipline is important. Doing

what needs doing does not always guarantee feeling good or

getting rewarded in accord with your expectations. Here’s a case

in point. I remember trying to put these concepts into practice

some time ago and came home one day to find a bunch of dishes

in the sink that my wife had yet to clean. Ok, I’m [feeling] resentful

that I’ve worked all day and here are dirty dishes that need to be

washed and [I think] my wife is supposed to wash the dishes.Alas,

I am now Mr. CL and will put on my CL outfit and wash the dishes

despite feeling crappy and resentful. Now that I’ve done the dishes

I am expecting my wife to be so overcome with gratitude that she’ll](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2d2e1552-de6e-4bdc-ab82-97110fc0cf25-160917112325/85/GUIDE-TO-ED-RECOVERY-2016-92-320.jpg)

![88

rather following a prescribed program (as noted above) and letting

go of the outcome – namely not making changes in response to

feelings, fears, or temporary changes in our bodies. Allowing

someone other than us, at least in the beginning, direct our food

and exercise plans is a far more objective and ultimately successful

means of finding a solution to the mental tyranny of trying to do it

alone. To be sure, it takes a quantum leap of faith and courage to

“turn over” control to someone other than yourself. In the end,

sponsorship in an appropriate support group such as OA or ABA,

making good use of a trusted and experienced professional, and

cultivating a belief in your own understanding of a higher power

will put you on the path to reclaiming your life”.

Marty Lerner, Ph.D.

It’s All About the Food…Isn’t it?

A food plan is not meant to be a “diet” in the traditional sense of

the word. It is better viewed as akin to comfortable clothing rather

than a straightjacket. It may change and be adjusted over time and

is not a “quick fix” or the be all and end all to treating an eating

disorder. However, it is an integral piece of the recoverypuzzle.

Although the term abstinence refers to the cessation of eating

disordered behaviors, whether binge eating, restricting, purging,

and so on, it also can refer to the specific boundaries regarding

properties of foods [types and amounts] within the plan. In](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2d2e1552-de6e-4bdc-ab82-97110fc0cf25-160917112325/85/GUIDE-TO-ED-RECOVERY-2016-100-320.jpg)

![92

“SERF” and not with manipulating the body to reflect a certain

number or conform to the body image du jour. The “trust” and

“control” issues we spoke about before have to do with trusting

your body’s response to a healthy food and exercise plan and

letting go of trying to control your body’s set point at any cost.

The measuring aspect of recovery as it relates to the food plan is

to weigh and measure our food and not our bodies. Doing so

avoids the tendency to over or under do what’s called for on our

food plan and serves as a teaching tool. It is not intended to

aggravate our compulsive nature, but rather to focus on following

a part of our recovery plan. Whether one continues to do so after

a few weeks or months of recovery becomes an individual choice.

Perhaps the same can be said for being weighed periodically by

yourself or someone else. If the benefits [excuse the pun]

outweigh the negative effects, fine. For most people, relying on

other measures of what’s happening with our bodies such as how

our clothes are fitting, etc. are enough.

Measuring Recovery – How am I Doing?

This is a really short topic. I would encourage anyone with an

eating disorder, or any addiction for that matter, to measure

progress in terms of how one is doing rather than how one maybe

feeling at a given time. Quite frequently, we may be feeling bad](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2d2e1552-de6e-4bdc-ab82-97110fc0cf25-160917112325/85/GUIDE-TO-ED-RECOVERY-2016-104-320.jpg)

![95

S.E.R.F. Lessons

Let’s see how many metaphors we can come up with for the SERF

stuff. “Stay close on your SERF board or you might drown.” Ok, ok,

how about – “The key to SERF-ing is all about balance” – I likethat

one. I’m done. Thanks for indulging me.

Spirituality – Give me an “S”

A quick disclaimer, I am no guru or authority on the subject

of spirituality. In the context of eating disorder recovery Iwould

suggest spirituality is, however, an integral part of ongoing

recovery. Defining spirituality is, at best, ambiguous. That may

be a good thing since there are no rules or religious dogma

attached to its practice. It affords anyone and everyone an

opportunity to participate. So let me attempt to bring together

two concepts that permeate the 12-step addiction recovery

literature – spirituality and powerlessness.

First, allow me to quote from Elisa Goldberg’s workbook used as

a text for her course on Spirituality in Behavioral Health Care

Settings [Drexel University -October, 2013].

“Spirituality is an essential element of human experience. It

represents the part of us that searches for meaning, seeks out](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2d2e1552-de6e-4bdc-ab82-97110fc0cf25-160917112325/85/GUIDE-TO-ED-RECOVERY-2016-107-320.jpg)

![99

Just as an aside, our bodies respond to excessive exercise and

activity [burning too much energy] with fighting for survival. It does

so by conserving energy. Thus, too much exercise and your body’s

metabolism will slow down in an effort to fend off starvation and

tissue loss. In other words, too much exercise and too little food

begins to demand more exercise and less and less food to maintain

continued weight loss or prevent weight gain. Anyone remember

what symptom of addiction this refers to? That’s right – it’s

TOLERANCE. Developing tolerance requires more of the same

behaviors or substances to achieve the same effect. I guess we

could say again this is about “getting caught in your own mouse

trap.” Likewise, the loss of a regular menses signals the body is not

able to withstand the rigors of child bearing while in survival mode

and protects itself by slowing down energy expenditure,

decreasing sex drive, and reverting the body back to an almost pre-

adolescent state.

With the “too little exercise” end of the spectrum, we are caught

up in the spiral of inertia. With an inadequate amount of activity

the body responds in ways that make it ever more difficult to dig

ourselves out of the hole we’ve dug. Our metabolism slows and

our energy levels decrease. We can find ourselves developing

metabolic diseases such as adult onset diabetes [Type II Diabetes]

with increasing insulin resistance. Our overall muscle mass](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2d2e1552-de6e-4bdc-ab82-97110fc0cf25-160917112325/85/GUIDE-TO-ED-RECOVERY-2016-111-320.jpg)

![101

decreases and we begin to associate feeling exhausted with

“thinking” we need to feed ourselves.

Moderate exercise is difficult to figure out objectively when in the

midst of an eating disorder. Like hunger perception and body

image, it can be confusing at best. With the amounts of food, we

tend to overestimate and under estimate what’s needed for our

recovery. It’s best to have someone with experience suggest a

reasonable exercise / activity plan along with a food plan in the

beginning. Individual needs will vary in accord with ones’ level of

fitness, their body mass, medical history, and so on. Suffice it to

say, moderate exercise should consider the following factors – for

example, frequency [3-5X weekly], duration [20-60 minutes],

intensity [60-80% of MHR]* may be guidelines.

*Aerobic intensity is usually measured by a formula that considers

someone’s age, max heart rate, etc. For our purposes, intensity can

be equated with being able to carry on a conversation while

exercising without losing your breath.

Rest – The Balance between Work and Play –

Give me an “R”

Ok, for some of us it may be “all work and no play” and of course

for others, "all play and no work.” The proper balance between

work and play is an essential piece of the recovery puzzle. I suspect](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2d2e1552-de6e-4bdc-ab82-97110fc0cf25-160917112325/85/GUIDE-TO-ED-RECOVERY-2016-112-320.jpg)

![102

interpret mental stress as physical stress and think physical

inactivity is in order. Indeed, what needs doing in this instance is

rest that involves activity and movement [aka exercise]. Physical

activity serves to balance emotional stimulation and intellectual

activity balances physical exertion. Physical work necessitates

physical rest while intellectual pursuits require physical activity to

restore balance. All this may sound confusing, but will make sense

after you experience it for a period of time. Whether a person

needs rest by intellectual challenges, physical activity, or play will

vary in accord with their circumstance and daily routines.

Last, but certainly not least, is sleep. Providing yourself with

adequate time to allow for 7-8 hours of sleep nightly is sound

advice. However, it should be mentioned that almost everyone

new in recovery has some difficulty with sleep – usually not able to

fall asleep and/or stay asleep. Sleep is one of the few behaviors we

have limited control over. Over time and with continued recovery

the sleep cycle rights itself and sleep follows a healthy and

predictable rhythm. During the initial part of your recovery you

may benefit from a non-addictive medication. Short of that, I

would suggest providing yourself with ample time to rest and, even

if not sleeping, begin the habit of being consistent with a time for

sleeping. If you are having a problem with sleeping at night, know

this will pass over time. Be careful not to nap or sleep during the](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2d2e1552-de6e-4bdc-ab82-97110fc0cf25-160917112325/85/GUIDE-TO-ED-RECOVERY-2016-114-320.jpg)

![103

daytime while your body is making adjustments to a sleep cycle in

sync with recovery.

Food Plans: Food for Thought – Give me an “F”

Rather than enter the “great food debate” and subject you to more

repetition of what has already been discussed, this section is

relatively short and [there’s that food pun again] sweet. The basics

[cooking pun now] boil down to eliminating sugar, flour, and highly

processed, high-glycemic foods, and controlling the volume of

food on the plan. There is also the suggestion of weighing and

measuring portions to insure accurate portions given the notorious

tendency among us to “distort” amounts.

I want to repeat once again and be perfectly clear the food plan is

not a diet, but a set of boundaries around eating. It is intended to

become a comfortable experience over time and not to function as

a set of handcuffs. The food plan is simply healthy eating,

eliminating junk foods, and insurance against either overeating or

under eating. It is subject to modification and adjustment under

the direction of someone other than you. It has an ability to be

flexible, but not at the expense of certain established boundaries.

Think of it as medication – something you neither prescribe nor

change without talking it over with the person responsible for

prescribing it in the first place.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2d2e1552-de6e-4bdc-ab82-97110fc0cf25-160917112325/85/GUIDE-TO-ED-RECOVERY-2016-115-320.jpg)

![112

change others. However, we do have the ability to change

ourselves. This brings us to an important point*.

The point is to not insist on finding someone who makes the grade

or trying to force someone into becoming our version of these

attributes. The real challenge is becoming the4As.

Relationships in Recovery – “Rules of the Road”

- Water seeks its' own level when it comes to relationships. In

other words, “birds of a feather tend to flock together.” Stick with

the winners in recovery.

- Relationships do not remain the same when one or both people

in a relationship begin recovery. There is a shift in the balance of

power.

- Often acts of [responsible] independence can be perceived as

acts of betrayal when new recovery behaviors begin to emerge.

- As recovery progresses, the tendency is to trade in approval for

respect from others – aka people pleasing decreases and

assertiveness begins to replace it.

- Priorities start to shift in recovery. The need to control others

starts to diminish over time.

- The experience of walking into a room full of people and

wondering “who is going to like me” starts changing to “who do I](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2d2e1552-de6e-4bdc-ab82-97110fc0cf25-160917112325/85/GUIDE-TO-ED-RECOVERY-2016-124-320.jpg)

![114

people. Perhaps something to give a little thought to - but then

take action with. The 4 A checklist can give you a general idea of

just how you’re doing "and what still needs doing.”

Compliance vs Acceptance and Surrender

A frequently overlooked phenomenon within the recovering

community, aka 12-step oriented fellowships, is a true

understanding of the subtle difference between being compliant

and truly accepting ones’ “addiction.” A growing number of

professionals, not to mention the recovering community at large,

have long understood addiction is a disease with a common set of

symptoms and characteristics. In most instances these symptoms

are both psychological and physical in nature. Whether we’re

speaking of alcohol, drugs, compulsive gambling, or the different

manifestations of disordered eating [inclusive of compulsive

eating, binge eating disorder, bulimia, or anorexia] they all sharea

similar sort of “DNA.” I would refer the reader back to the

professionals charged with defining the symptoms of an addiction

outlined earlier in this book in Chapter 1. Formulated by the

American Psychiatric Association’s Task Force on Addiction, the

consensus stands today as the “Gold Standard” for diagnosing

addiction. In effect, this is one way of restating the difference

between a bad habit and an authentic disease entity.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2d2e1552-de6e-4bdc-ab82-97110fc0cf25-160917112325/85/GUIDE-TO-ED-RECOVERY-2016-126-320.jpg)

![115

Should we look beyond the substance, or for that matter most

compulsive behavior[s], we begin to see what separates those who

enjoy long-term recovery from those who tend to repeatedly

relapse. In other words, exploring the nature of the person and not

simply the nature of the substance or behavior. What follows

comes in large measure from the original works of Harry Tiebout,

M.D., and William Silkworth, M.D. Both men were pioneers in the

field who treated countless numbers of alcoholics and addicts.

Each understood the physical and psychological aspects of

addiction and, in their own way, shed light on what makes

someone suffering with an addiction different from their non-

afflicted peers.

Compliance, Acceptance, Surrender - A Process, Not an Event

Let me begin by clarifying these concepts and elaborating upon the

practical implications of each of these states of mind. Let’s begin

with the notion of compliance. To paraphrase Dr. Tiebout,

compliance refers to an individual “agreeing, going along with, but

in no way implies enthusiastic, wholehearted approval”. Usually

there is a willingness not to argue or resist and although

cooperation exists, it comes with some reservations. In other

words, one is not entirely happy about agreeing or following “the

party line.” The willingness to, let’s say abstain from certain foods,

drink, or substances is somewhat shaky. Suffice it to say it doesn’t](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2d2e1552-de6e-4bdc-ab82-97110fc0cf25-160917112325/85/GUIDE-TO-ED-RECOVERY-2016-127-320.jpg)

![116

take much to shift from compliance to relapse. Although the good

doctor speculates this is an “unconscious” phenomenon, I would

disagree. Most people in early recovery have some very conscious

reservations about their “lack of power” [aka lack of control] and

insist on stepping back into the ring after a brief period of

remission. Perhaps we can say compliance is a close cousin to

denial.

Understanding the specific dynamics of acceptance is tantamount

to understanding what separates those with long term recovery

from those who experience only brief periods of recovery.

Continuing with Tiebout’s observations:

“Acceptance appears to be a state of mind in which the individual

accepts rather than rejects or resists: he is able to take things in, to

go along with, to cooperate, to be receptive. He/She is not

argumentative, quarrelsome, irritable or contentious. For the time

being, at any rate, the hostile, negative, aggressive elements are in

abeyance, and we have a much more pleasant human being to deal

with. Acceptance, as a state of mind, has many highly admirable

qualities, as well as, useful ones. Some measure of it is greatly to

be desired. Its’ attainment as an inner state of mind is never easy.”

– Harry M Tiebout, M.D.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2d2e1552-de6e-4bdc-ab82-97110fc0cf25-160917112325/85/GUIDE-TO-ED-RECOVERY-2016-128-320.jpg)

![117

In my experience the transition from compliance to acceptance is

a process rather than an event. As such the period of time from

which a person moves from a compliant stance to an acceptance

state of mind varies greatly. However, I would add to Tiebout’s

thesis, getting from point A to point B is quite similar to what we’ve

come to understand as the stages we all go through upon suffering

a loss. [On Death and Dying: E. Kubler-Ross, 1969]. Letting go of

our primary “reward” or “feel good” thing is no easy task. To be

sure, it is a great loss if you suffer from the disease of addiction.

The experience of transitioning to acceptance, and to that of total

surrender, will encompass the following stages:

DENIAL

ANGER

BARGAINING

DEPRESSION

ACCEPTANCE

As with other losses, one can expect to negotiate these in a

sometimes back and forth pattern, vacillating between stages until

arriving at the final stage of acceptance. It is coming to rest at the

acceptance level that one can understand and experience the act

of surrender. It is here one can sense a lifting of the obsession, no

longer needing to struggle with abstinence, but rather finding a

comfort and rhythm to recovery. Ambivalence about recovery](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2d2e1552-de6e-4bdc-ab82-97110fc0cf25-160917112325/85/GUIDE-TO-ED-RECOVERY-2016-129-320.jpg)

![118

dissolves and intervals of serenity and acceptance of “life on life’s

terms” begin to increase.

Over the years Tiebout believed this “conversion experience” is

exemplified by:

• The switch from negative to positive behavior by the

act of surrender

• The cessation of defiance and grandiosity: attaining a sense

of humility

• Surrender being synonymous with a marked change

in behavior[s].

• Surrender, when maintained, exerts a positive influence on all

spheres of ones’ life: physical, emotional, and spiritual.

In effect, getting to this stage in recovery can be viewed as the

precise moment when the tendency toward defiance and ego

driven self-control cease to function effectively. With this, the

individual is totally open to accepting reality. Honesty, open-

mindedness, and willingness replace the negativity and

grandiosity, often the least attractive personality traits common to

most addicts. As the good doctor reminds us, “the act of surrender

is an occasion wherein the individual no longer fights life, but

accepts it.” My suspicion is this process coincides with the

progression of spiritual growth. In effect, there is an acceptance of](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2d2e1552-de6e-4bdc-ab82-97110fc0cf25-160917112325/85/GUIDE-TO-ED-RECOVERY-2016-130-320.jpg)

![119

humility and a healthy balance between appropriate self-reliance

and reliance on something other than one’s self [ego].

Marty Lerner, Ph.D.

The Transition Home

The most important piece of the treatment experience is the ability

to transfer your experiences to the real world, namely continuing

in recovery after returning home. No one does this perfectly. The

whole idea of recovery is not for it to become your life, but to

enable you to get a life. That being said, your success will greatly

depend on having practiced daily living skills during your time in

treatment. The actual experiences of doing the grocery shopping

and food preparation, attending OA, ABA, and other relevant

groups, following an exercise plan, finding a balance with work,

rest and play, and all the other behaviors associated with

maintaining an eating disorder free life, will enhance your chances

for continued recovery at home. To the degree your last day in a

treatment program is a close fit to your next day home, is the

extent to which you have benefited from your hard work. Once

more, intellectual knowledge of recovery has little to do with the

understanding coming from the doing part.

Continuing your recovery still involves a level of commitment after

you leave the treatment setting. Rather than propose a long

dissertation as to what needs doing for “life after treatment,”](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2d2e1552-de6e-4bdc-ab82-97110fc0cf25-160917112325/85/GUIDE-TO-ED-RECOVERY-2016-131-320.jpg)

![121

suffice it to say that long-term recovery is a function of practicing

the S.E.R.F. formula on a consistent basis, as well as, working all

the steps of the 12-Step group you choose to follow. Doing this will

virtually insulate you from relapse if done on a regular basis. Like

taking care of ones’ self with any chronic illness, it will require

some effort and discipline day to day. However, as said before, it

is intended to allow you to “get a life” and not become your life.

Just put the [SERF] eggs in the bowl before the rest of the stuff that

seems to demand “all” your time and attention.

Summary

Before moving on, let’s take a moment and reflect on what’sbeen

discussed so far. Despite being a little too close to the forest

myself, I’m hopeful by now the reader has an appreciation ofboth

the nature of the problem and the suggestions for long-term

recovery.

We defined the problem in terms of the physical, emotional

[psychological] and spiritual consequences inherent with an eating

disorder. We looked at what all eating disorders have in common

rather than looking at them as separate entities. We saw the

similarities between an eating disorder and other forms of

dependencies and addictions. Looking forward, we began to better

understand the dynamics of both the disease and treatment.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2d2e1552-de6e-4bdc-ab82-97110fc0cf25-160917112325/85/GUIDE-TO-ED-RECOVERY-2016-132-320.jpg)

![132

S.M.A.R.T - An Alternative or Add-On to 12 Step

Organizations?

Reprint of a “Self Growth” article written [M. Lerner, Ph.D. 2014]

In the world of addiction treatment there are several choices one

has in the way of utilizing and attending a community based

support group. Should one look more closely at what is offered to

those with an eating disorder the choices are somewhat more

limited, but none-the-less do exist. This article takes a look at two

diverse, yet complimentary approaches, 12 Step oriented

programs and the SMART Recovery program.

A detailed description of both may be beyond the scope of this

article. However, suffice it to say both “philosophies” or “beliefs”

have inherent similarities, as well as, differences. To that end, I

hope to distinguish what each brings to the table that is unique and

what they share in common.

SMART Recovery Basics

Let’s begin with what SMART (SR) stands for, namely Self-

Management and Recovery Training. In a nutshell, SR offers a 4-

Point Program [not to be confused as “steps”] that amount to 1-

Building and Maintaining Motivation, 2- Coping with Urges, 3-

Managing Thoughts, Feelings, and Behaviors, and 4- Living a

Balanced Life. SR can serve as a stand-alone approach or](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2d2e1552-de6e-4bdc-ab82-97110fc0cf25-160917112325/85/GUIDE-TO-ED-RECOVERY-2016-144-320.jpg)

![133

compliment another program such as a 12-step group or

professional treatment. SR does not necessarily adhere to the

premise that one need attend meetings as part of a lifelong

process, as there is a beginning, middle and end to treatment for

an addiction. Hence once an “addict” you are not always an addict.

Another, what I believe to be very important distinction, SR is

intended to be open to support any addiction and does not hold

separate groups for compulsive overeaters, alcoholics, drug

addicts, compulsive gamblers, and affected family members.

Virtually anyone with an addictive or compulsive behavior[s] with

a desire for abstinence from these, may benefit from attendance

and are welcomed.

Having the benefit of experiencing both a 12-Step Program for

many years and, more recently becoming a trained facilitator for a

SMART Recovery group, I would say SR represents a more updated

approach to addictive problems. Although there are no bona fide

studies to support the efficacy of one support group over another,

there is ample research to support the effectiveness of the“tools”

and techniques taught in the groups. These include motivational

interviewing techniques, cognitive behavioral approaches to

confronting urges and destructive behaviors, and developing

alternate healthy lifestyles to replace addictive and compulsive

behaviors. SR encourages participants to take an active role in the

group process, and unlike the format of a 12-Step meeting, talking](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2d2e1552-de6e-4bdc-ab82-97110fc0cf25-160917112325/85/GUIDE-TO-ED-RECOVERY-2016-145-320.jpg)

![135

the other is discouraged and both programs promote a philosophy

of open mindedness and seeing what works best for anyone

seeking abstinence* from their addictive substance or behavior[s].

*Both programs support abstinence, but SMART does not require

abstinence from "everything," only those substances or activities

that are selected for abstinence by the participant.

While on the topic of similarities, it’s also important to note both

programs encourage the use of medical and relevant professionals

when appropriate, as an integral part the recovery process.

Inherent with that policy is the notion SMART Recovery and 12-

Step programs are there to serve as a support network and not a

substitute for medically necessary treatment when called for.

Indeed, one may argue there is a practical difference between a

support group and a treatment program. For a substance

dependent person medically supervised detoxification may be

indicated as a life-saving procedure. Likewise, for someone in the

grip of an eating disorder, medical stabilization and a structured

setting may be necessary to gain a foothold in the beginningstage

of the recovery journey. Yet for others, the frequently associated

mental health issues, such as depression, may require the use ofa

suitable medication, and so on. Although I could go on with a list

of other relevant common denominators, I would suggest

someone approach each with an open mind and experience both

groups a fair number of times, to be in a position to choose which,](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2d2e1552-de6e-4bdc-ab82-97110fc0cf25-160917112325/85/GUIDE-TO-ED-RECOVERY-2016-147-320.jpg)

![136

if not both, offer the best opportunity for continued abstinence.

Indeed, some people will choose one program over the other while

still others will see each group as offering something unique and

worthwhile – opting to attend both on an on-going basis.

To someone reading this with no prior experience with a 12-step

program, I would suggest it is, at least for me, difficult to put an

aggregate of experiences into words to adequately describe them.

What I would say, unlike SR meetings, 12-Step groups are intended

primarily for specific addictions and are not one “fellowship” but

many. In other words, alcoholics would attend an AA meeting

[Alcoholics Anonymous], Overeaters go to OA, Anorexics and

Bulimics [ABA], Compulsive Gamblers [GA], and so forth.Although

not a religious program, there is a strong current of encouraging

someone to work toward their own version of “a power greater

than themselves” or a sense of spirituality, without defining what

that should be for the individual. In this sense, the program is not

religious and purposely leaves the concept of a higher power

strictly up to the individual. To be sure, there are members who

have succeeded in these fellowships who are agnostic or atheists,

and there are no “musts” in the program as outlined in their

literature. The [suggested] steps represent a series of actions or a

progressive formula participants are encouraged to complete over

time – with the inherent belief that doing so will not only result in

continued abstinence, but also lead to a more productive and](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2d2e1552-de6e-4bdc-ab82-97110fc0cf25-160917112325/85/GUIDE-TO-ED-RECOVERY-2016-148-320.jpg)

![140

Understanding Insurance and the Cost ofTreatment

A clear and concise understanding of your insurance benefits and

what will or won’t be covered for an eating disorder [or a related

diagnosis] can be both confusing and overwhelming. As an

example, your insurance may list mental health as a covered

benefit [eating disorders fall within that category], but require you

to be “pre-certified” for a specific treatment [level of care]. In

doing so, the insurance company typically will utilize a set of

criteria to determine if the severity of your eating disorder meets

their criteria for “medical necessity”. As such, it’s possible you may

have the benefit, but are denied access to the program or level of

care you are looking for.

Typically, when someone considers coming to a residential, day

treatment, or intensive outpatient program such as ours, they

participate in a clinical assessment to determine their treatment

needs. Although most insurance benefits include mental health

benefits, including a residential program, a few do not.

However, assuming you do have benefits that include the

continuum of care [residential, partial hospital, and intensive

outpatient options], the provider or program will be better able to

estimate what will or will not be approved based on the findings of](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2d2e1552-de6e-4bdc-ab82-97110fc0cf25-160917112325/85/GUIDE-TO-ED-RECOVERY-2016-153-320.jpg)

![142

your clinical interview [assessment]. Often the assessment can be

conducted via a structured phone interview.

As if the above isn’t complicated and confusing enough, there is

also the matter of what your particular insurance policy requires

as a “deductible” and what your “co-pay” would be for particular

services. Usually, these will be a function of whether you are

requesting services from a “network” or “out of network”

provider. Out of network providers [facilities and providers] usually

involve a somewhat greater “out of pocket” expense on your part.

That said, the good news is that after you reach [spend] a specified

amount of your own money, your insurance will typically cover

100% of the remaining costs provided you are “certified” for the

treatment you’re requesting.

By way of example, someone coming to a program or provider

contracted with XYZ insurance, may have a $250 deductible and no

co-pay for residential treatment for an eating disorder. In this

instance, the maximum out of pocket expense or financial

responsibility for that person is limited to $250 – assuming

the insurance company’s medical criteria for that level of care is

met. Likewise, someone who has a different plan may have no

deductible and no co-pay, and hence have no out of pocket

expense. Lastly, someone who is using an out of network benefit

will likely still be covered after their deductible is met,and, in some

instances, have a small daily co-pay during theirstay.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2d2e1552-de6e-4bdc-ab82-97110fc0cf25-160917112325/85/GUIDE-TO-ED-RECOVERY-2016-154-320.jpg)

![143

Given all the above variables and possibilities, it comes down to

finding someone who can verify your benefits and be able to give

you a clear understanding of what to expect. In doing so, it is

important to realize some of the answers to your concerns can only

be estimated and predicted on past experiences with your

insurance company. This is because your insurance company will

not usually commit, in advance, to a specific length of stay at a

given setting or level of care. As such, you will want to know what

contingency plan exists should your insurance company [or your

managed care company] decide you no longer need treatment at

that level of care or program.

In effect, you may want to discuss your “worst case scenario”

before you commit to a treatment program, as well as, what the

most likely scenario will be. Unfortunately, there is typically some

element of uncertainty when dealing with insurance coverageand

treatment. Your job is to minimize this uncertainty, so you can

focus on the task of recovery. Here is where the experience and

integrity of the person reviewing your insurance is so important.

This process begins with a call to the provider or facility admissions

director. Knowing the proper questions to ask is important.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2d2e1552-de6e-4bdc-ab82-97110fc0cf25-160917112325/85/GUIDE-TO-ED-RECOVERY-2016-155-320.jpg)

![144

Here are a few questions to ask…

• Are you in-network with my insurance company?

If not, will you accept my out of network benefit?

• What is my out of network benefit and deductible?

• What is my daily co-pay, if any, at your program?

• What is the likely maximum out of pocket expense at

your facility for the level of care I need per day?

[e.g. residential, day treatment, or intensive outpatient]

• What can I expect my out of pocket expense will befor

the recommended length of stay

• What is the average length of stay at your program?

• Will I receive a bill for treatment after I leave?

• Will I know prior to admission what my insurance will and

will not pay for?

• Will you let me know beforehand, if there is any denial of

authorization for treatment, that I will be responsible

for later?](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2d2e1552-de6e-4bdc-ab82-97110fc0cf25-160917112325/85/GUIDE-TO-ED-RECOVERY-2016-156-320.jpg)

![146

Breakfast Pancakes, Oatmeal, CottageCheese

(2 servings)

1 ½ cups rolled oats

3 tbsp. oat bran

1/3 cups cottage cheese

3 egg whites