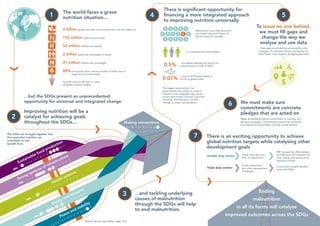

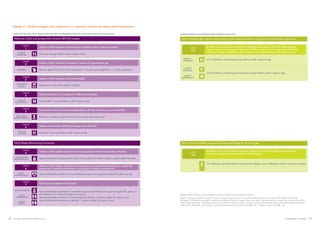

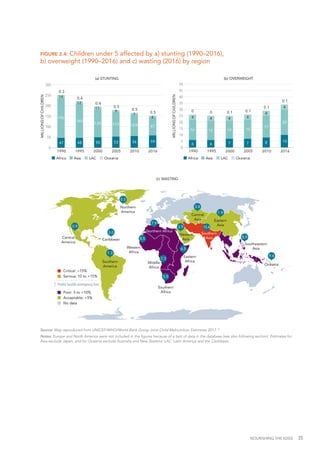

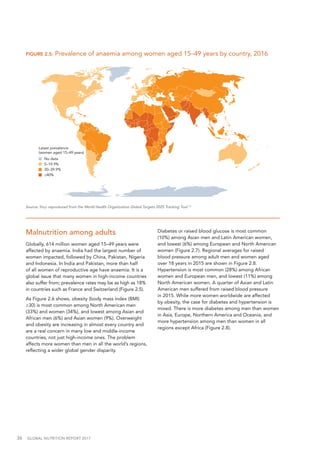

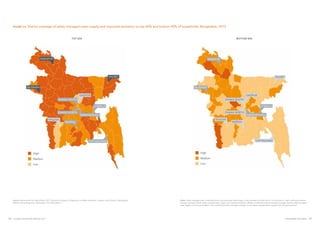

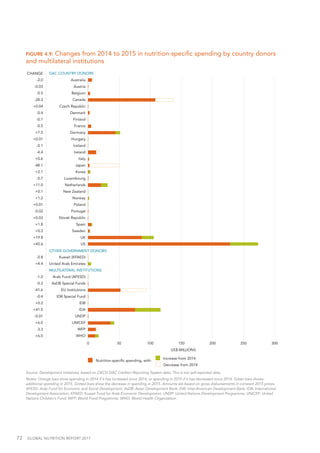

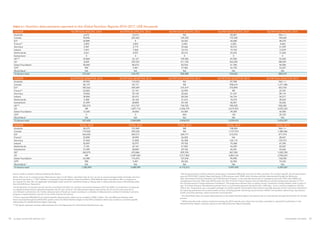

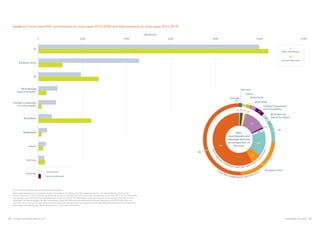

The Global Nutrition Report 2017 highlights the detrimental impact of malnutrition and stunting on Africa's economy, costing at least $25 billion annually and hindering progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). It emphasizes that good nutrition is crucial for achieving universal health coverage and that urgent action is necessary to combat malnutrition, which has worsened due to humanitarian crises. The report calls for a multi-sectoral approach and improved data to effectively address nutrition challenges globally.