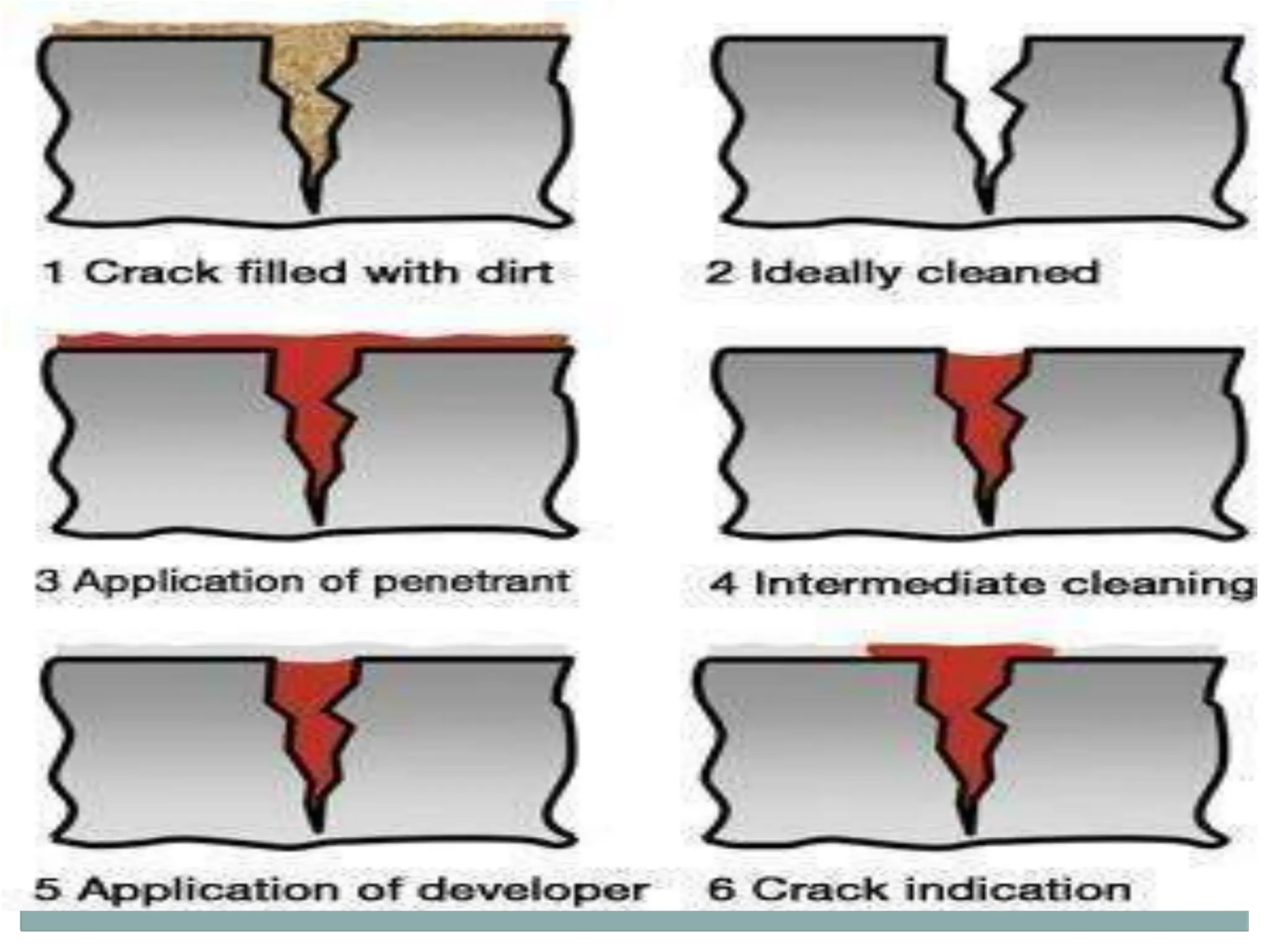

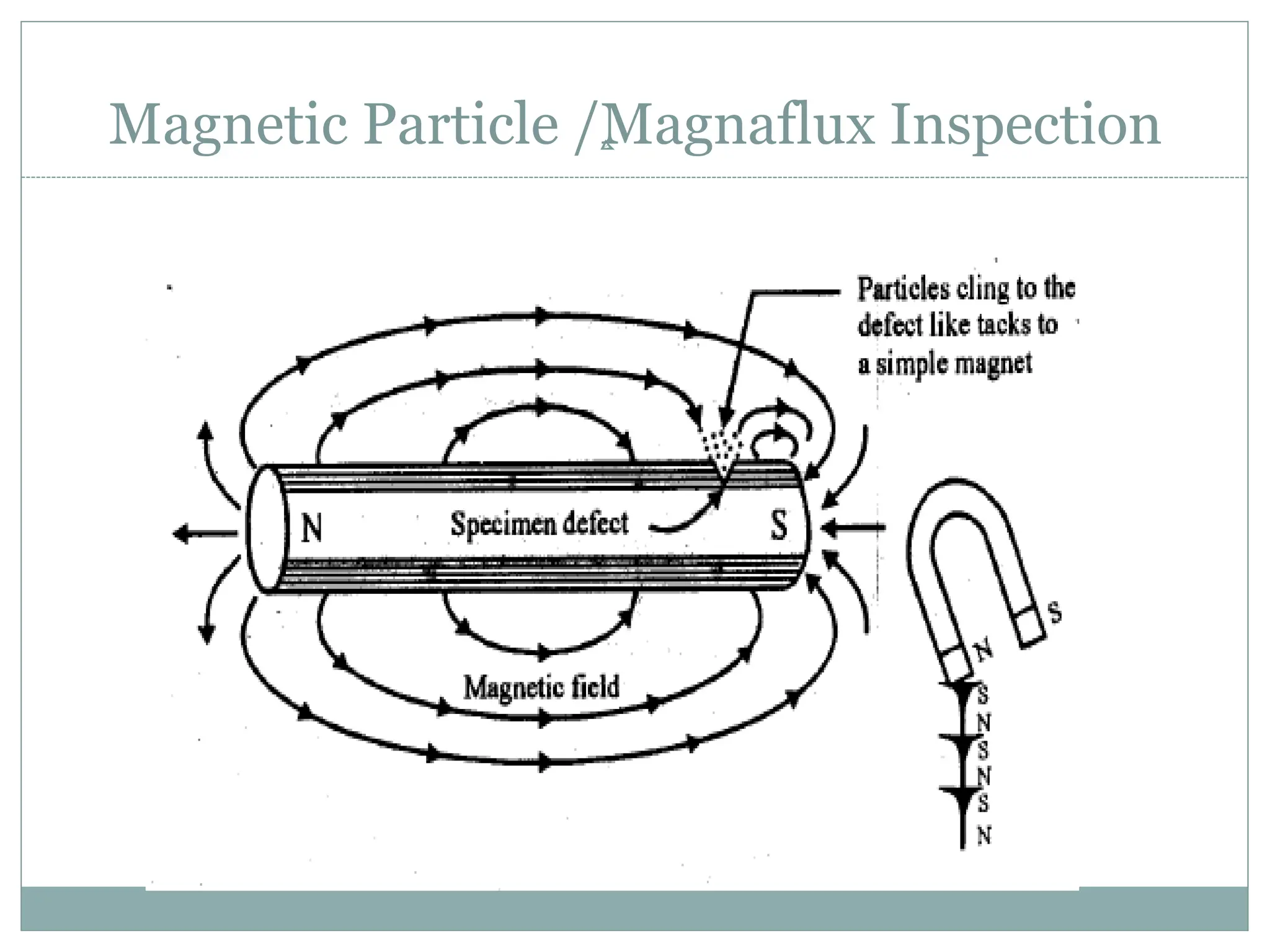

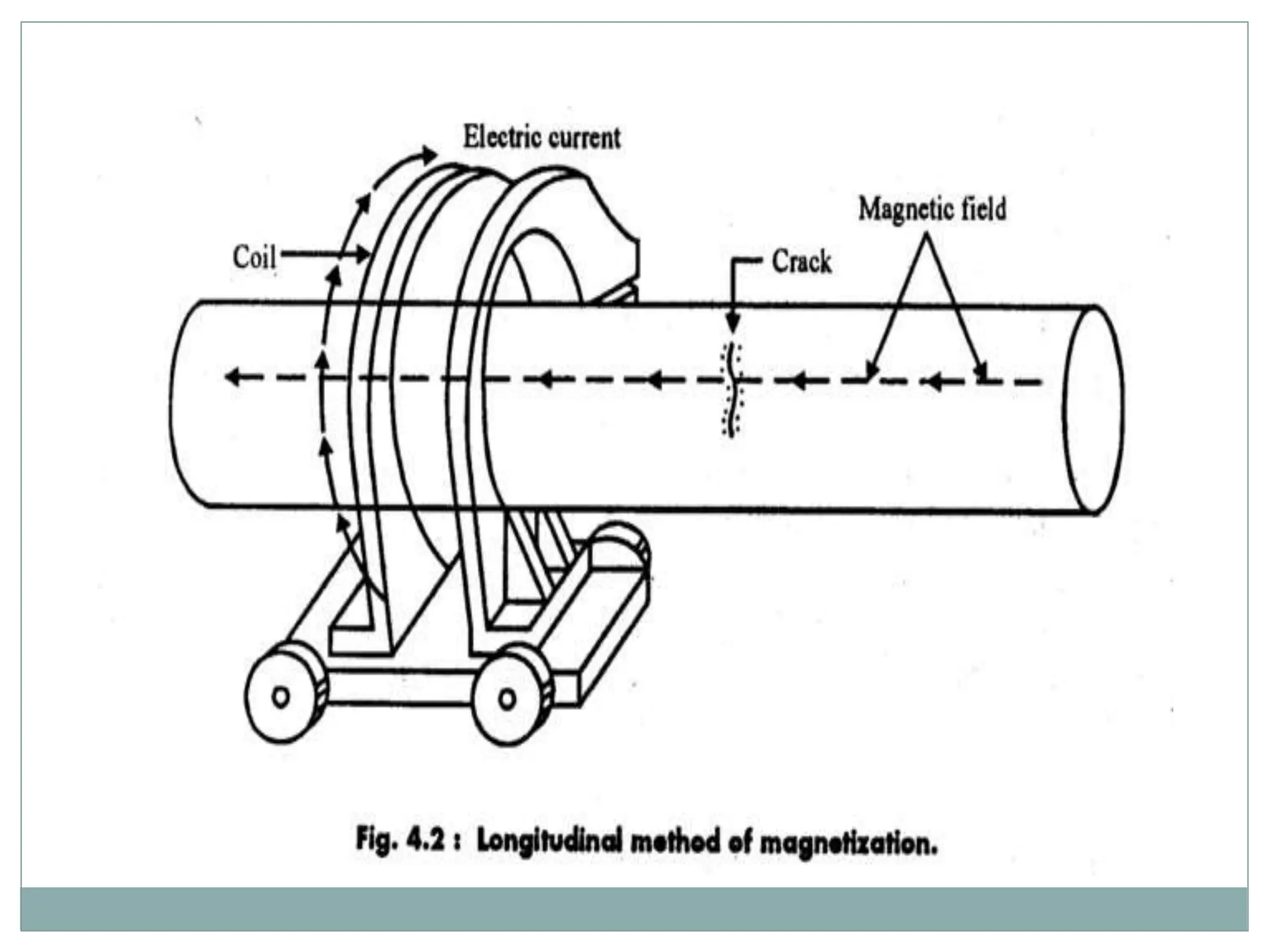

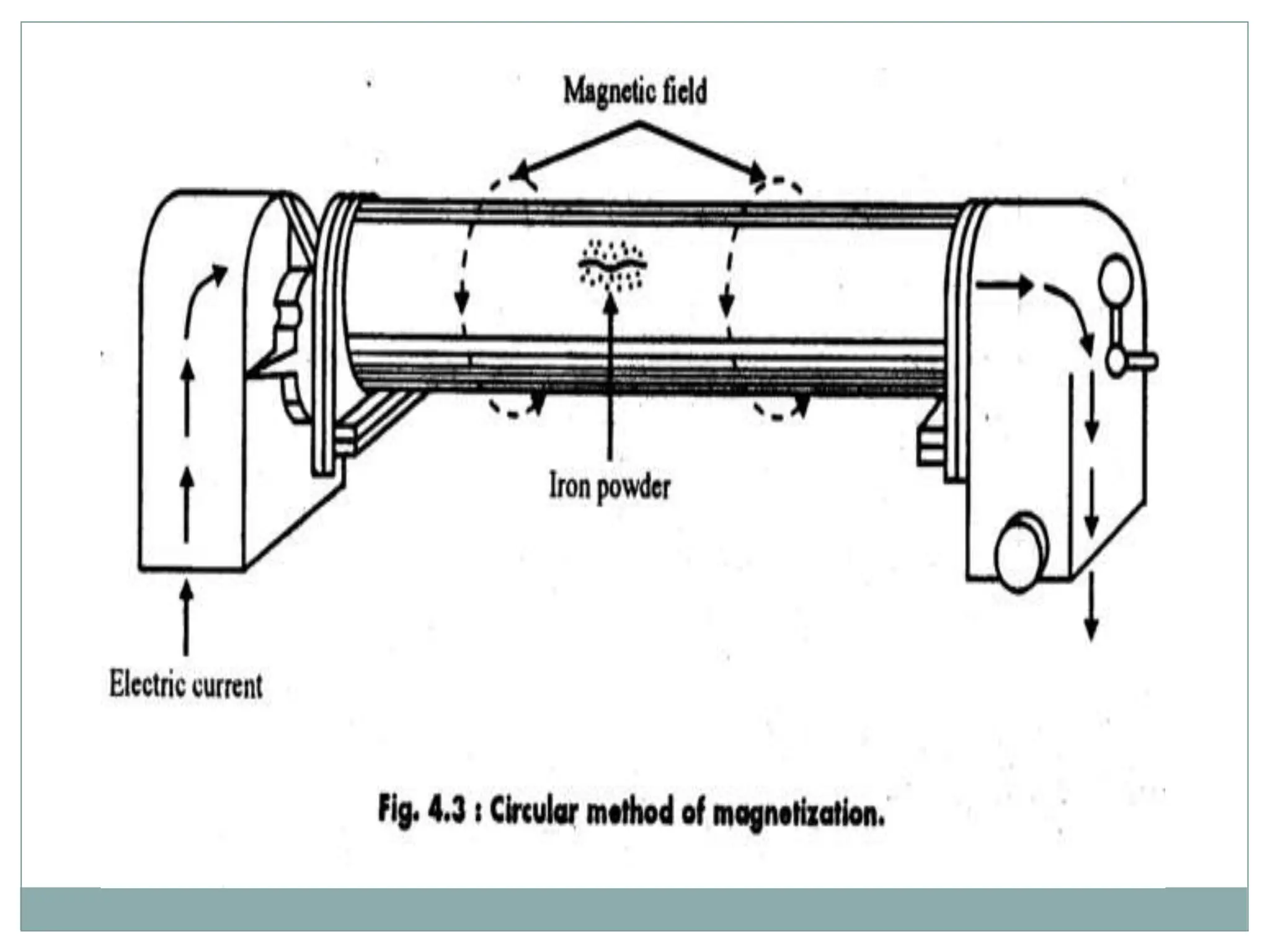

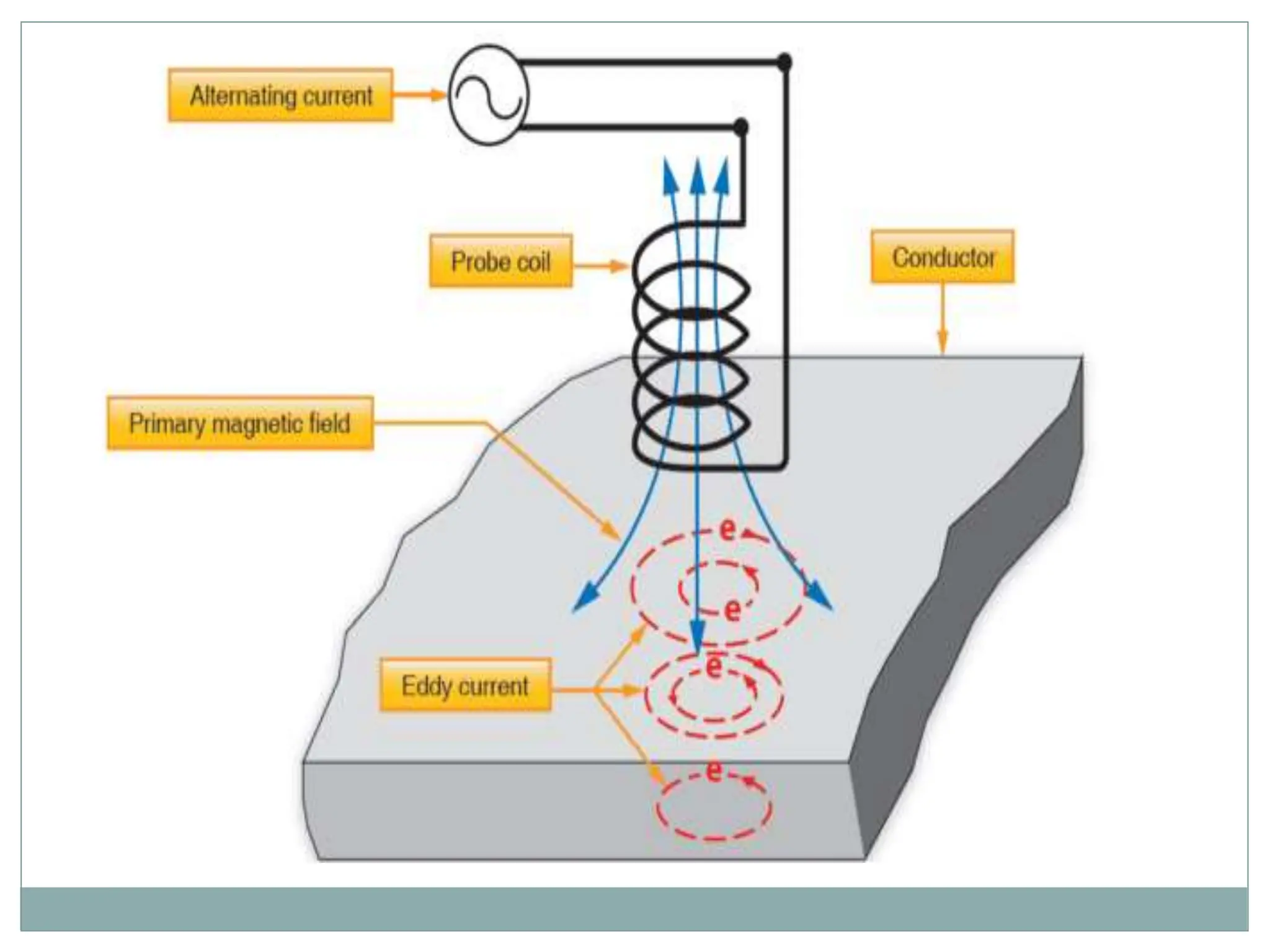

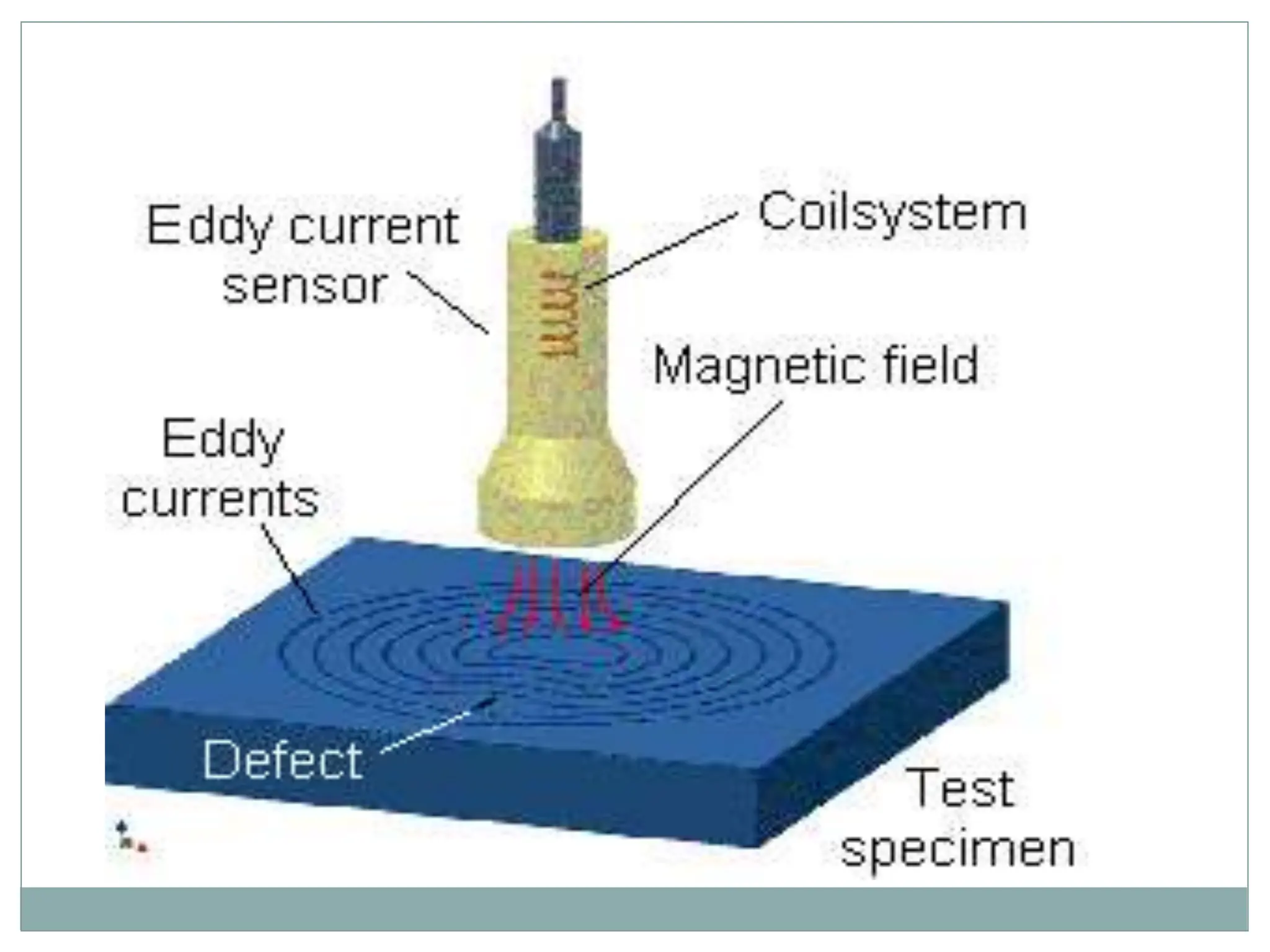

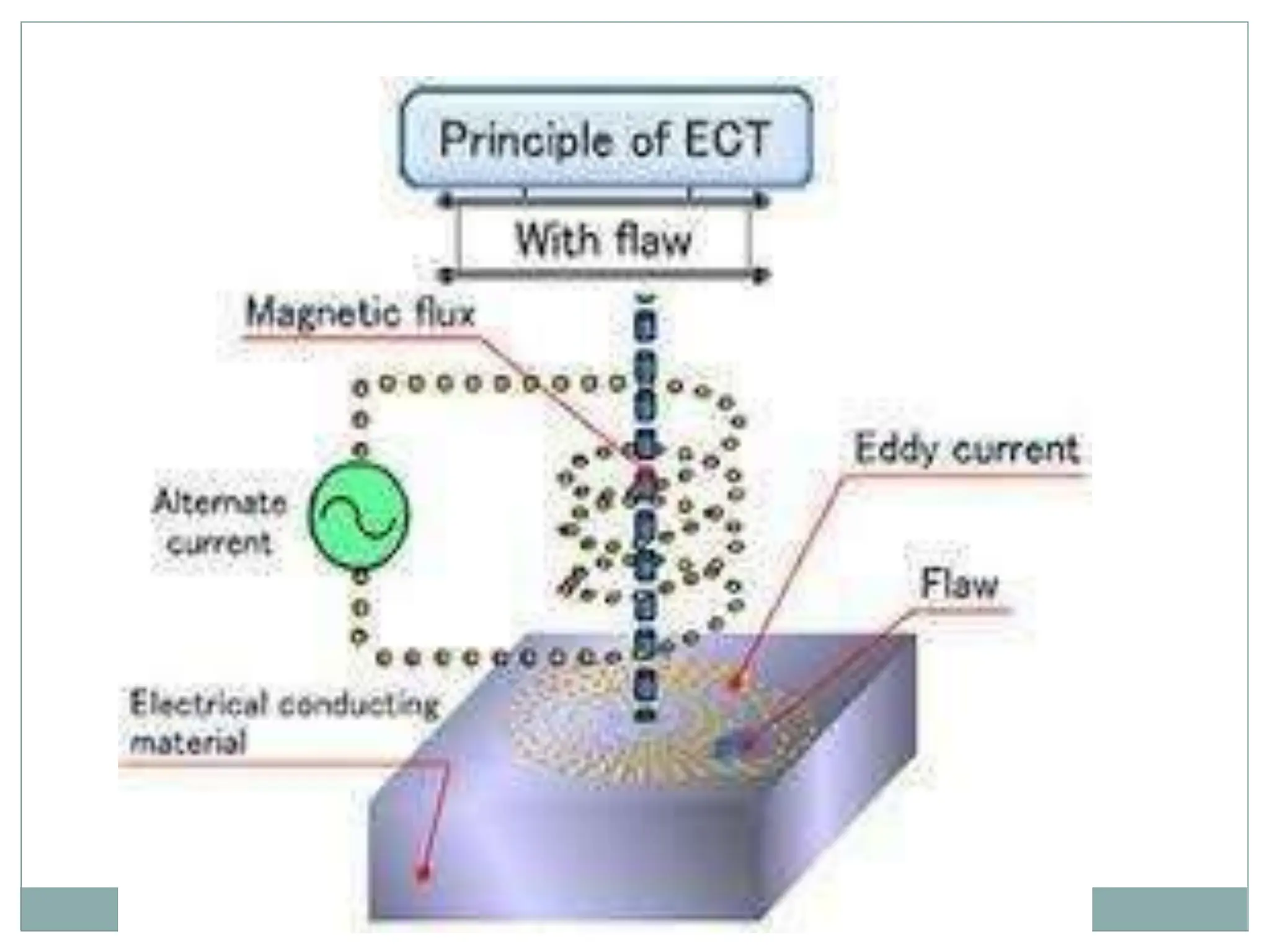

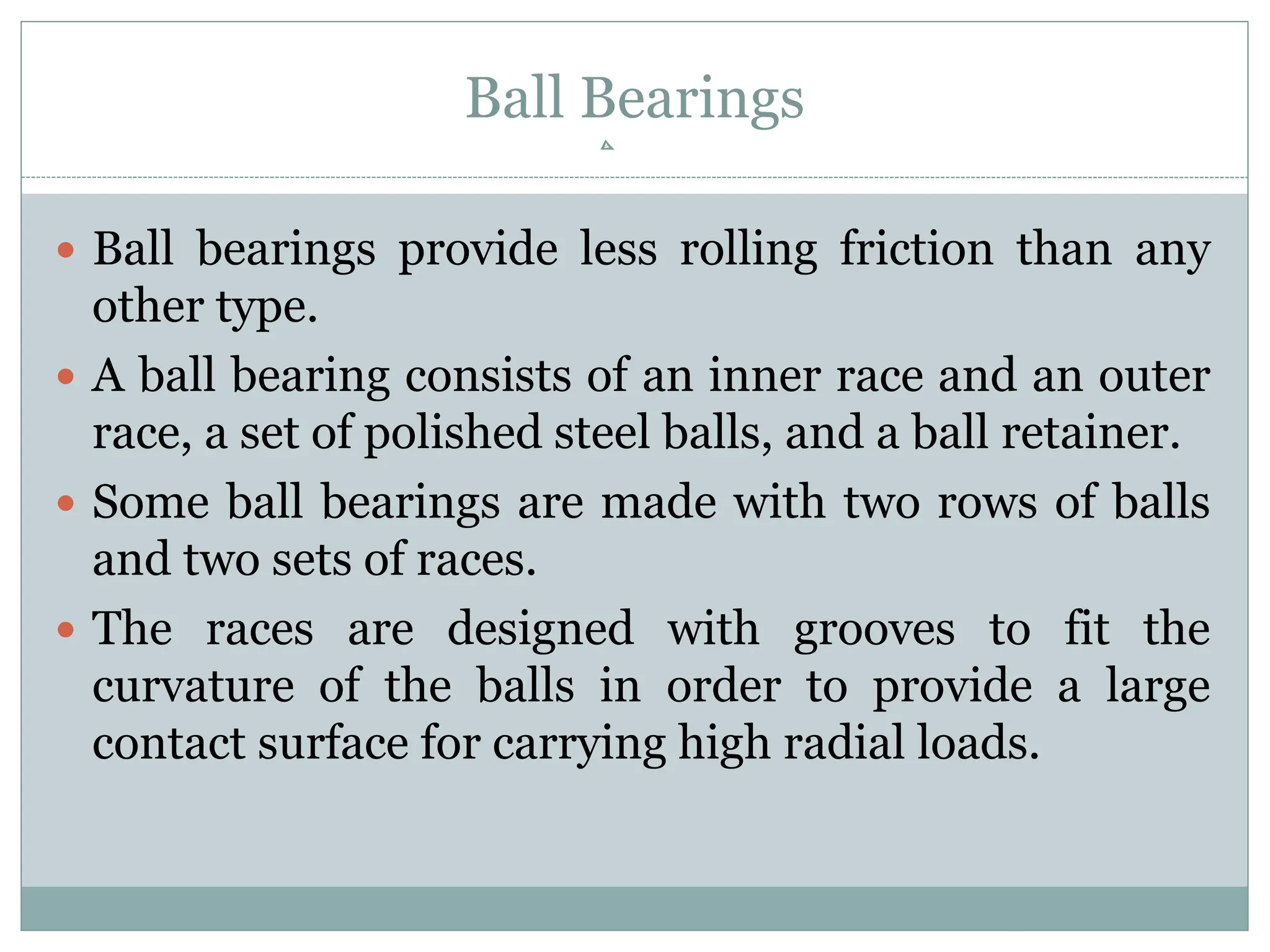

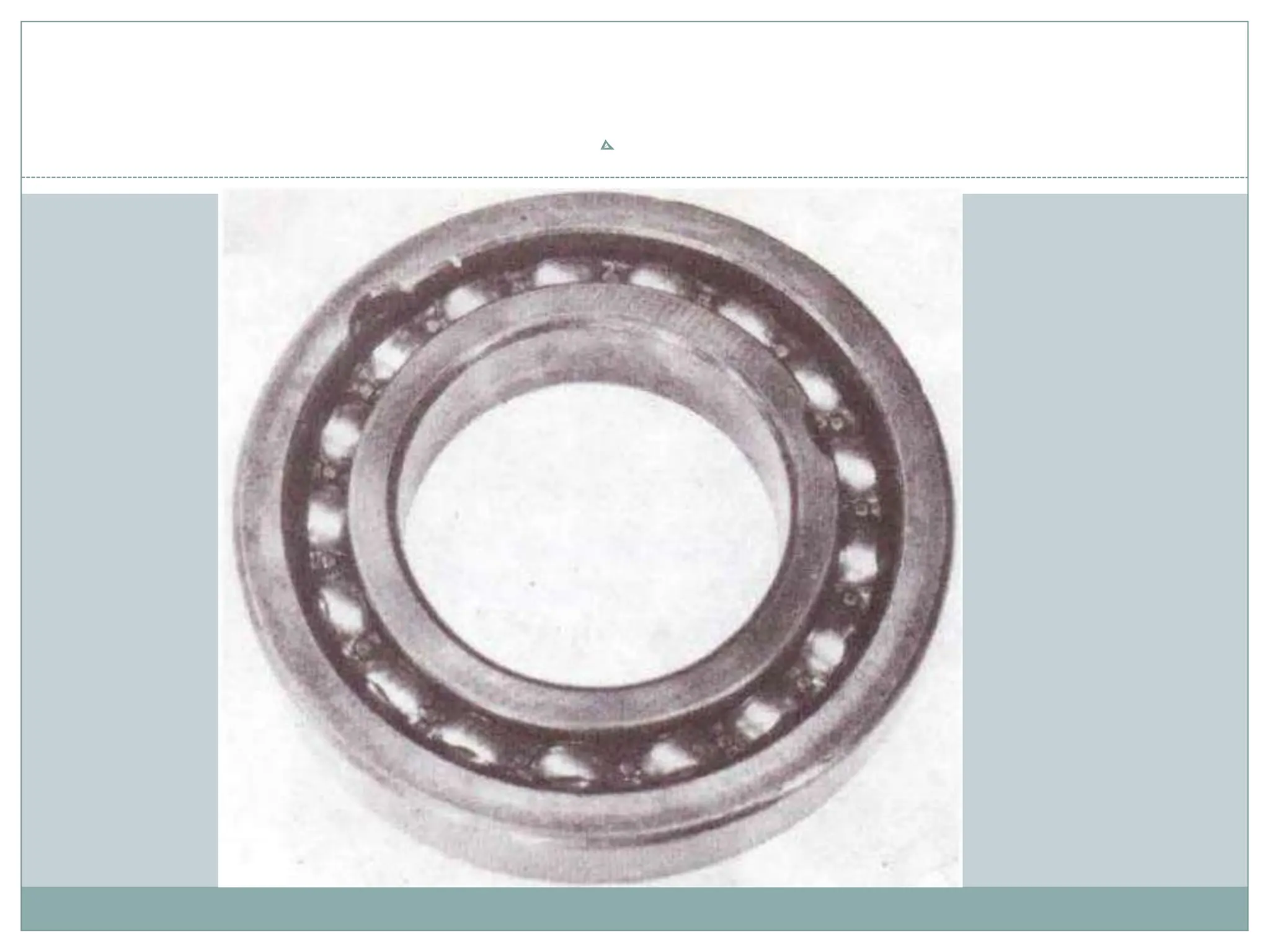

This document discusses general aircraft inspection procedures and techniques. It covers topics such as visual inspections, checklists, publications used for inspections like manuals and airworthiness directives, non-destructive testing methods, and special inspections required after events like hard landings, turbulence, or lightning strikes. The goal of inspections is to determine an aircraft's airworthiness and identify any defects or needed maintenance through systematic examination of its components and systems.