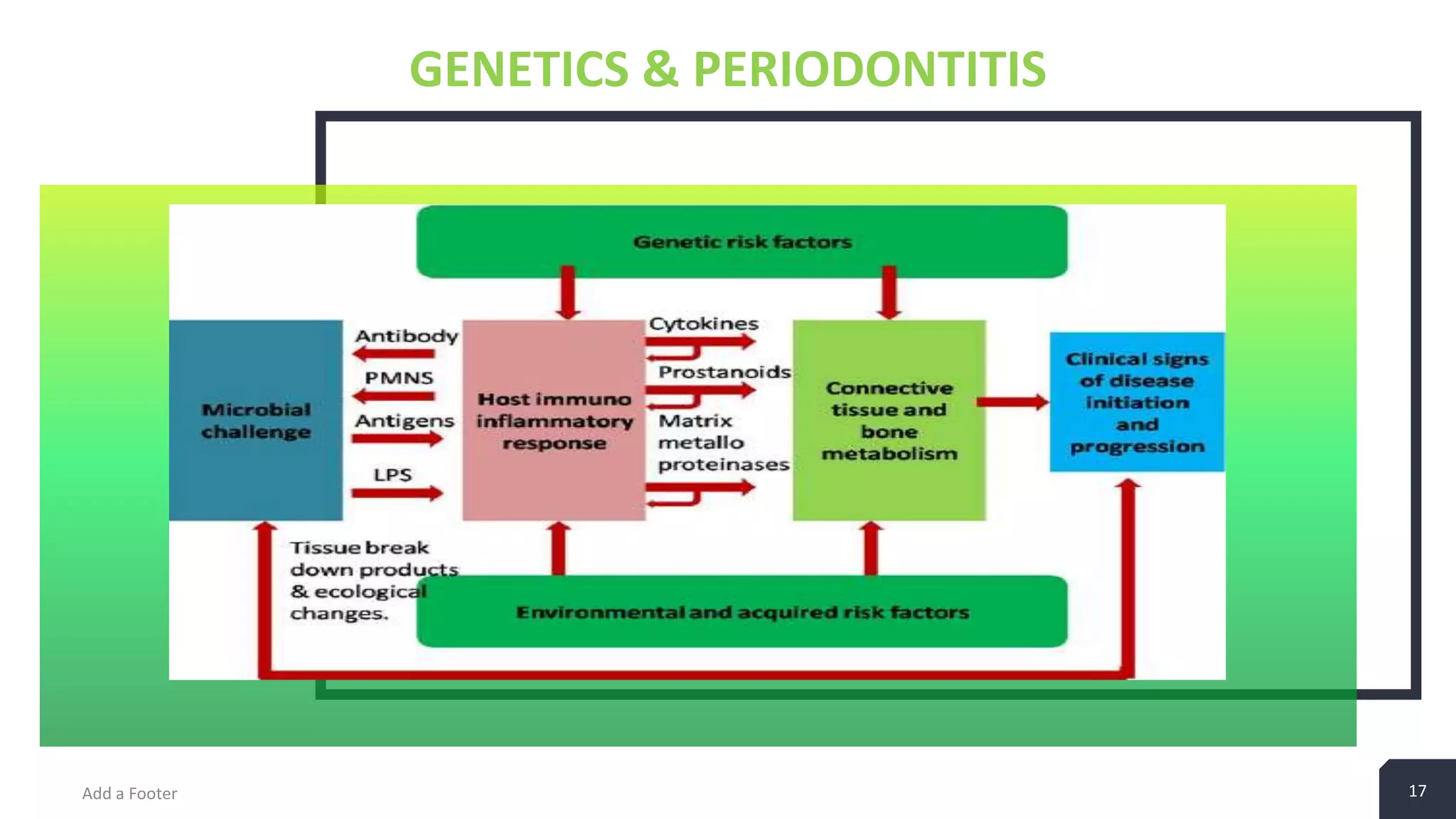

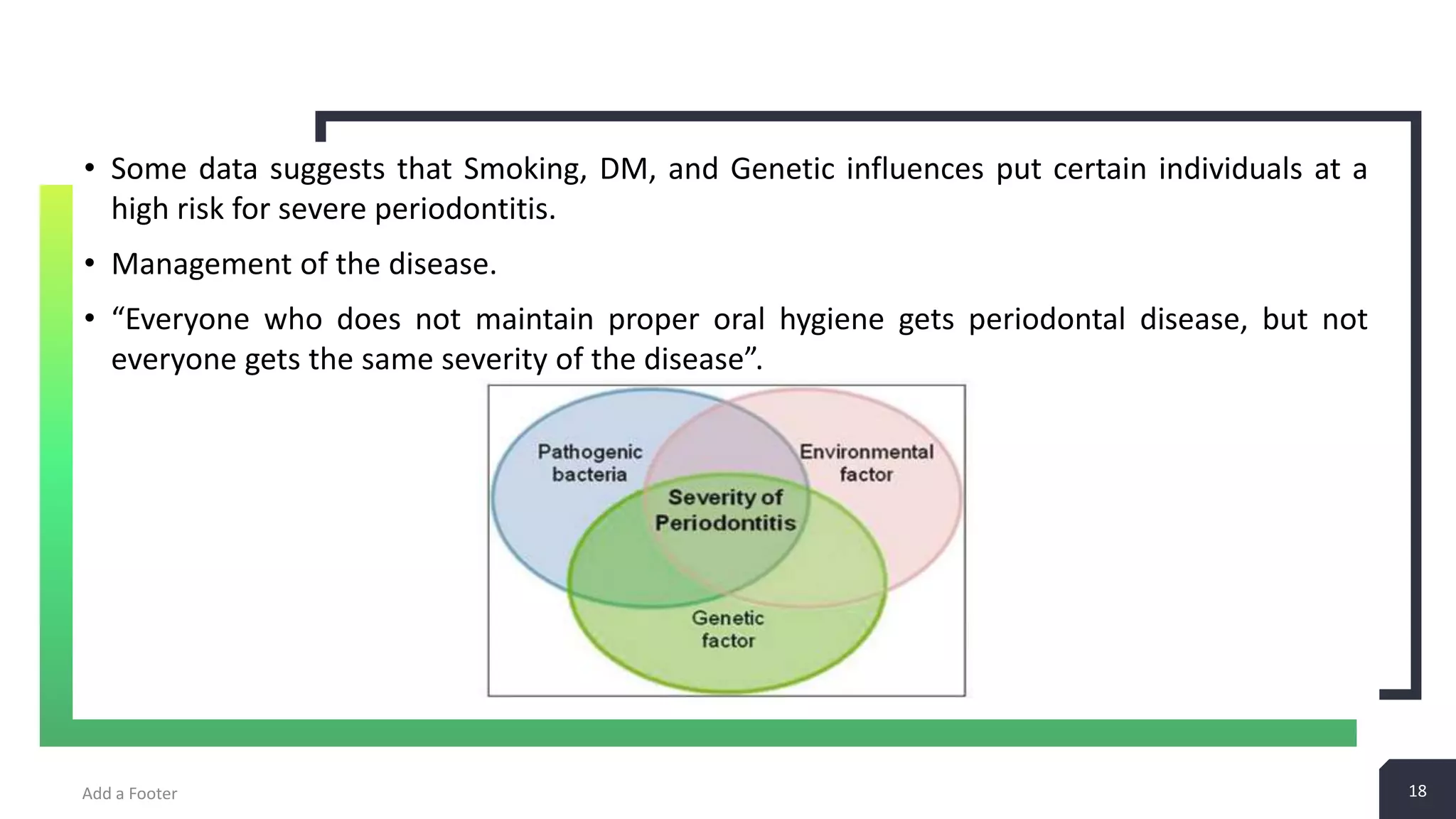

This document discusses genetics and periodontics. It provides an introduction to genetics concepts like genes, genomes, alleles and genetic testing. It discusses the human genome project and evidence that genetics plays a role in periodontal diseases. Certain genes like IL-1, TNF-α and PGE2 are candidates for influencing periodontal diseases based on their roles in immune-inflammatory processes and bone metabolism. Genetic variations involved in periodontal diseases can be determined through studies of candidate genes, genomic scans and proteomics.