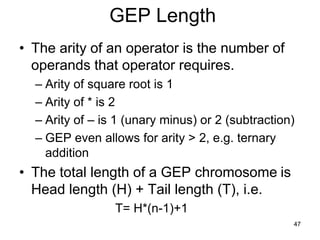

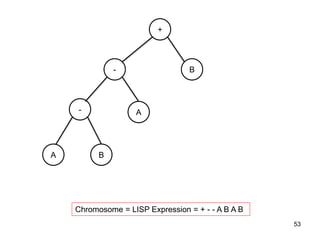

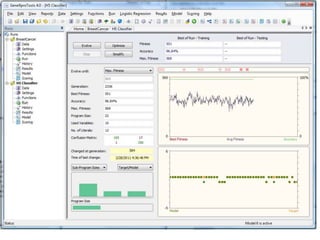

Genetic programming (GP), created by Cramer in 1985 and later expanded by Koza in 1992, focuses on finding a function and its parameters to optimize a given function based solely on input-output data. The GP system operates differently from genetic algorithms, particularly in fitness evaluations, and utilizes programming languages like Lisp to handle chromosome structures, including operations such as crossover and mutation. Gene expression programming (GEP) is a newer approach that utilizes fixed-length chromosomes representing variable-length expressions, simplifying some of the complexities present in traditional GP methods.