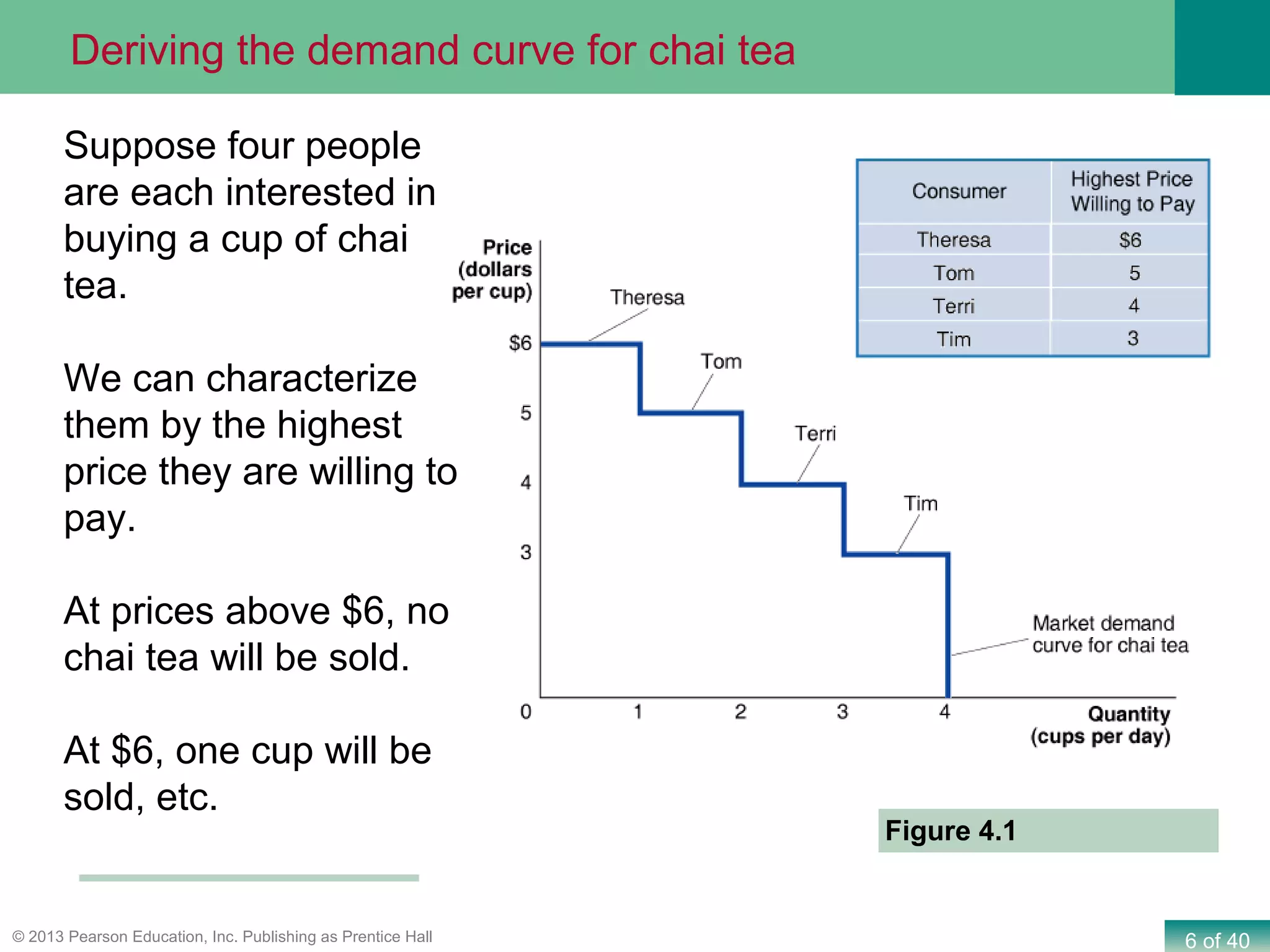

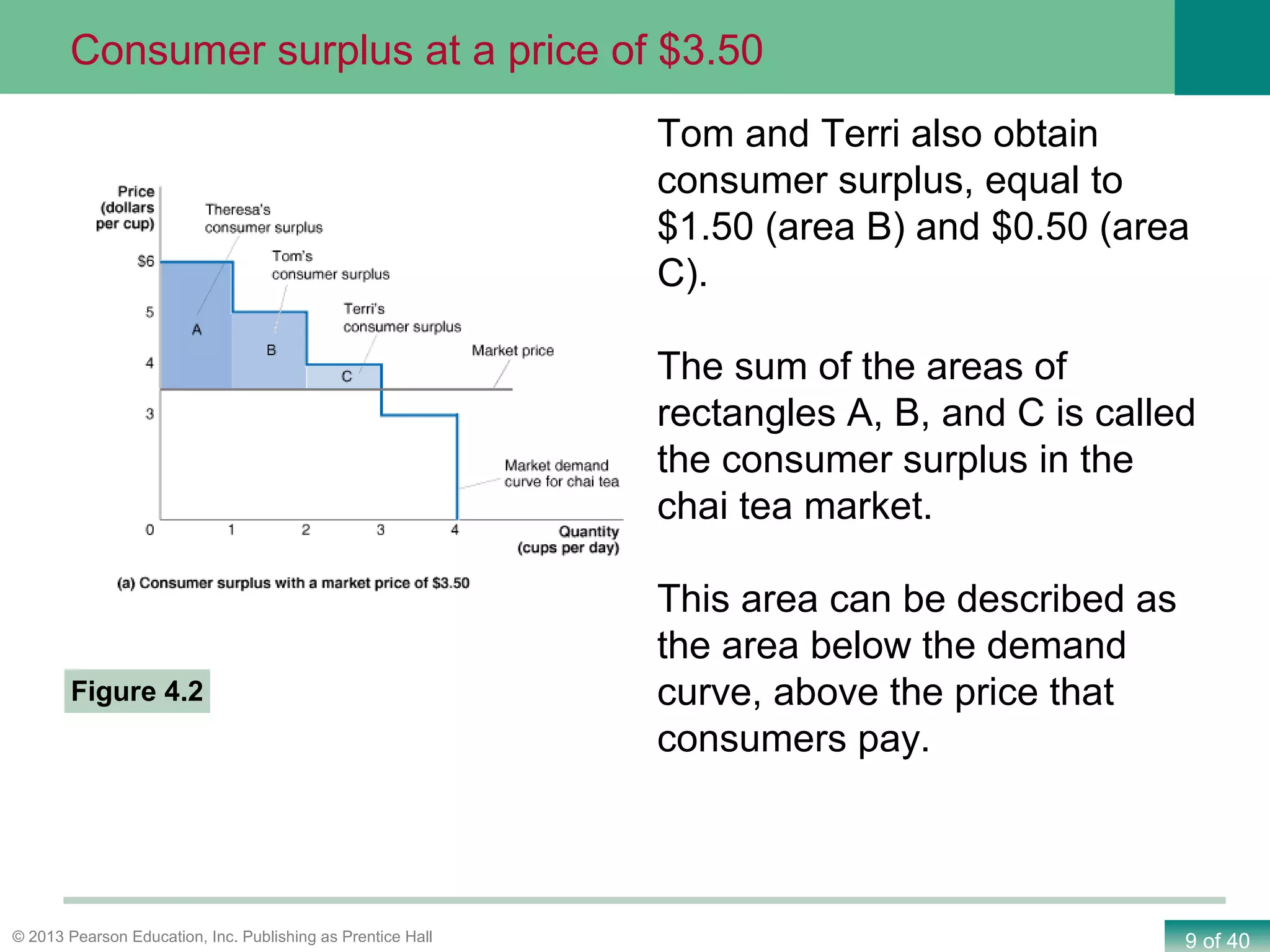

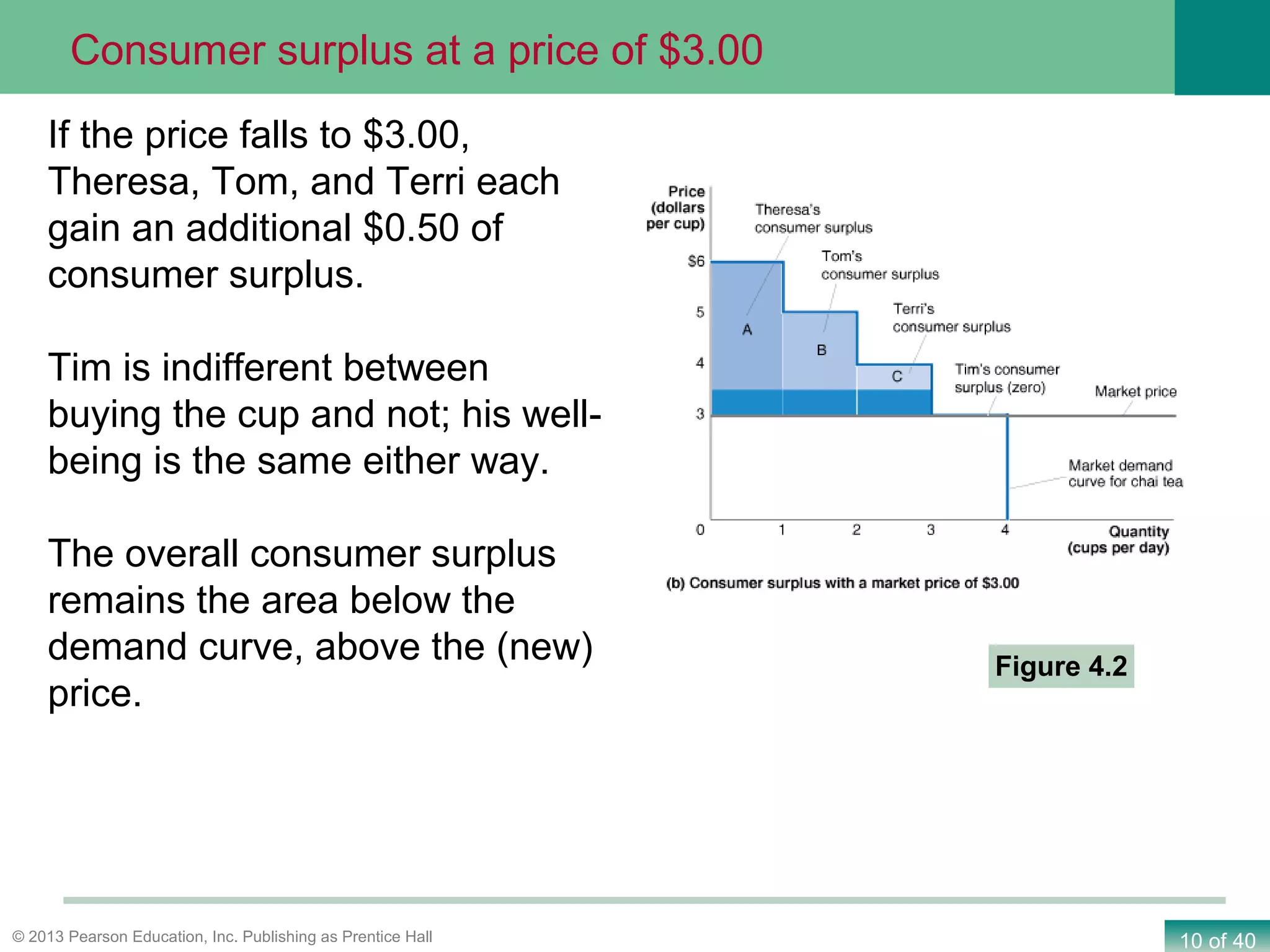

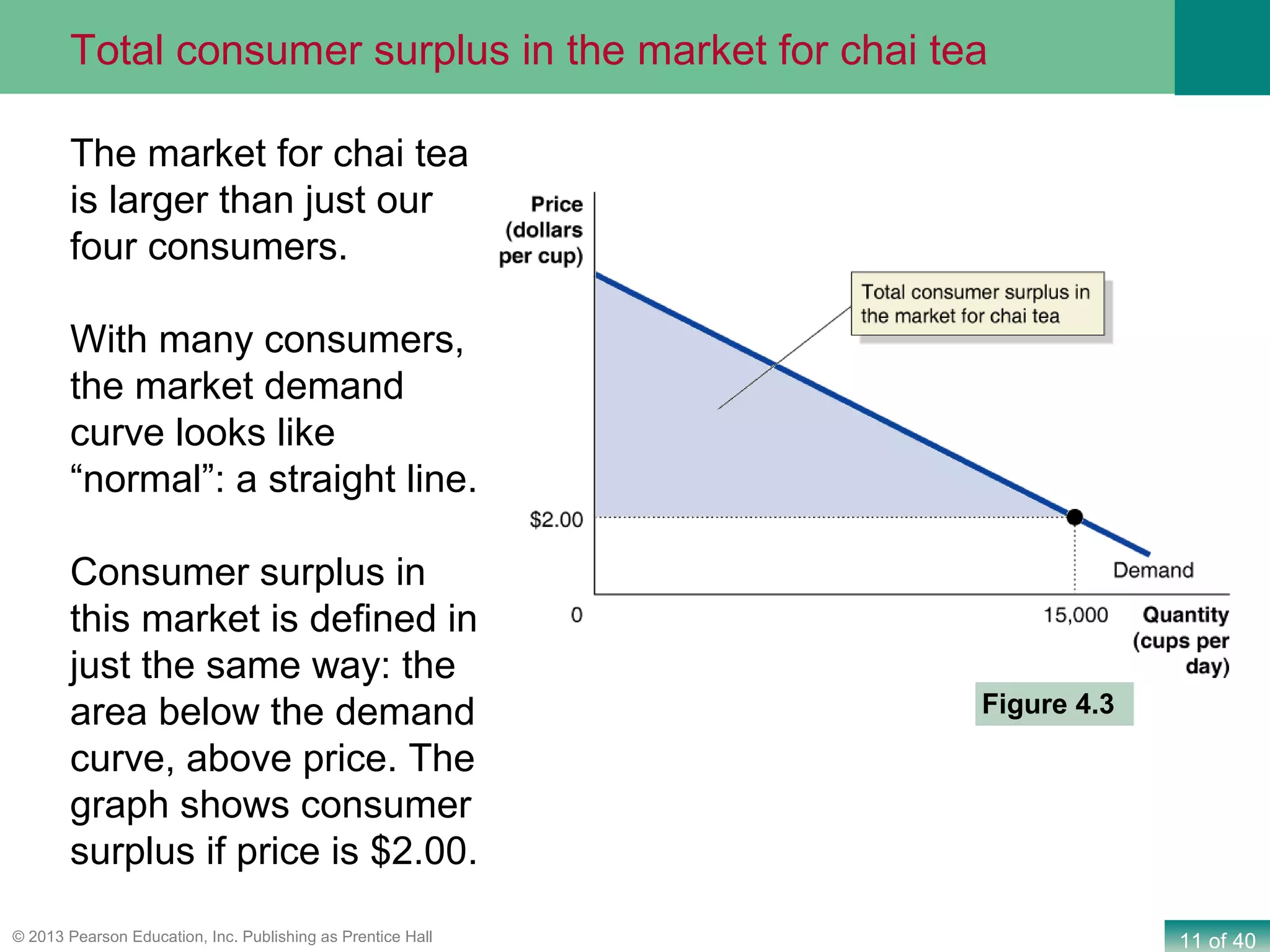

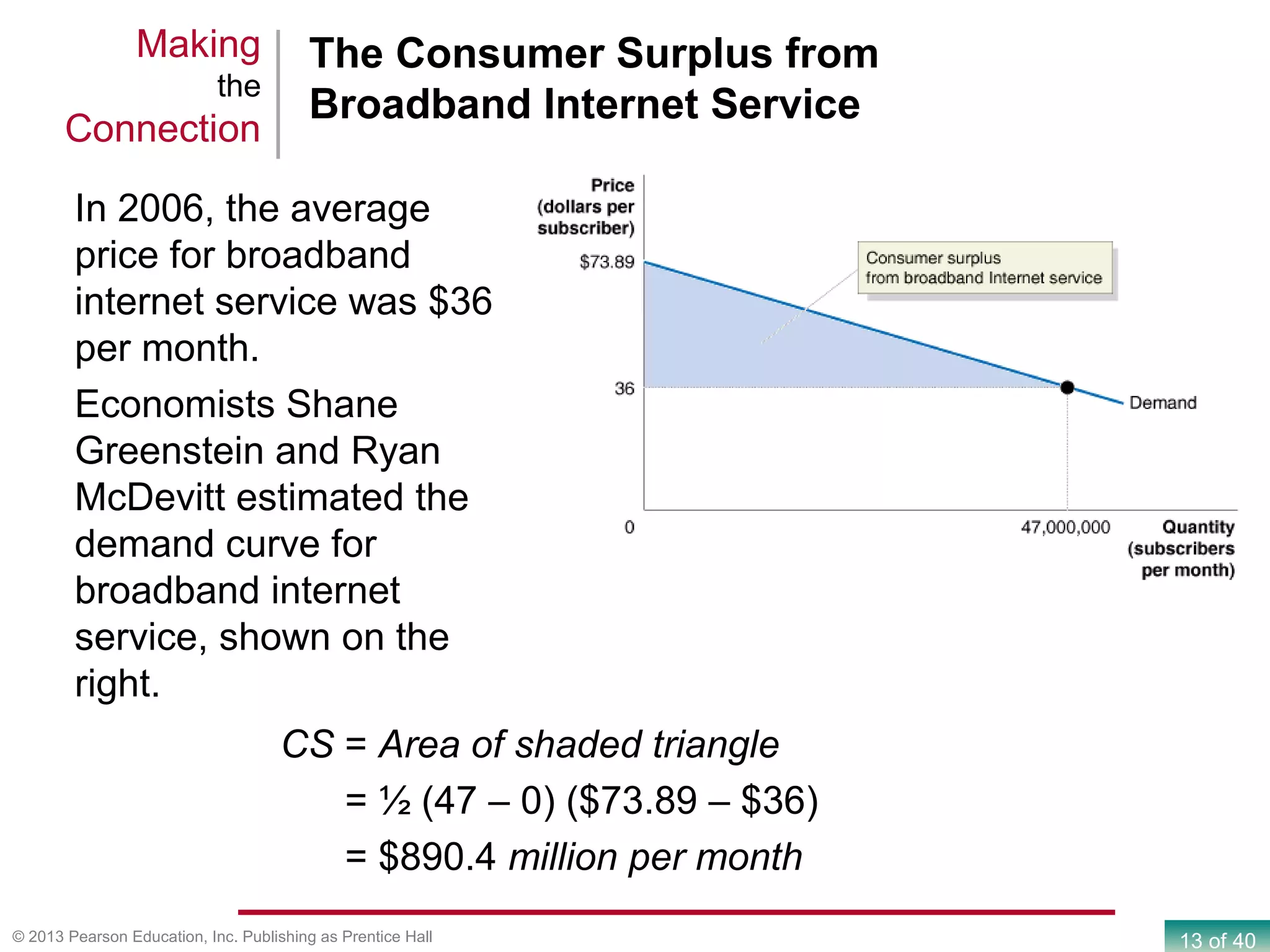

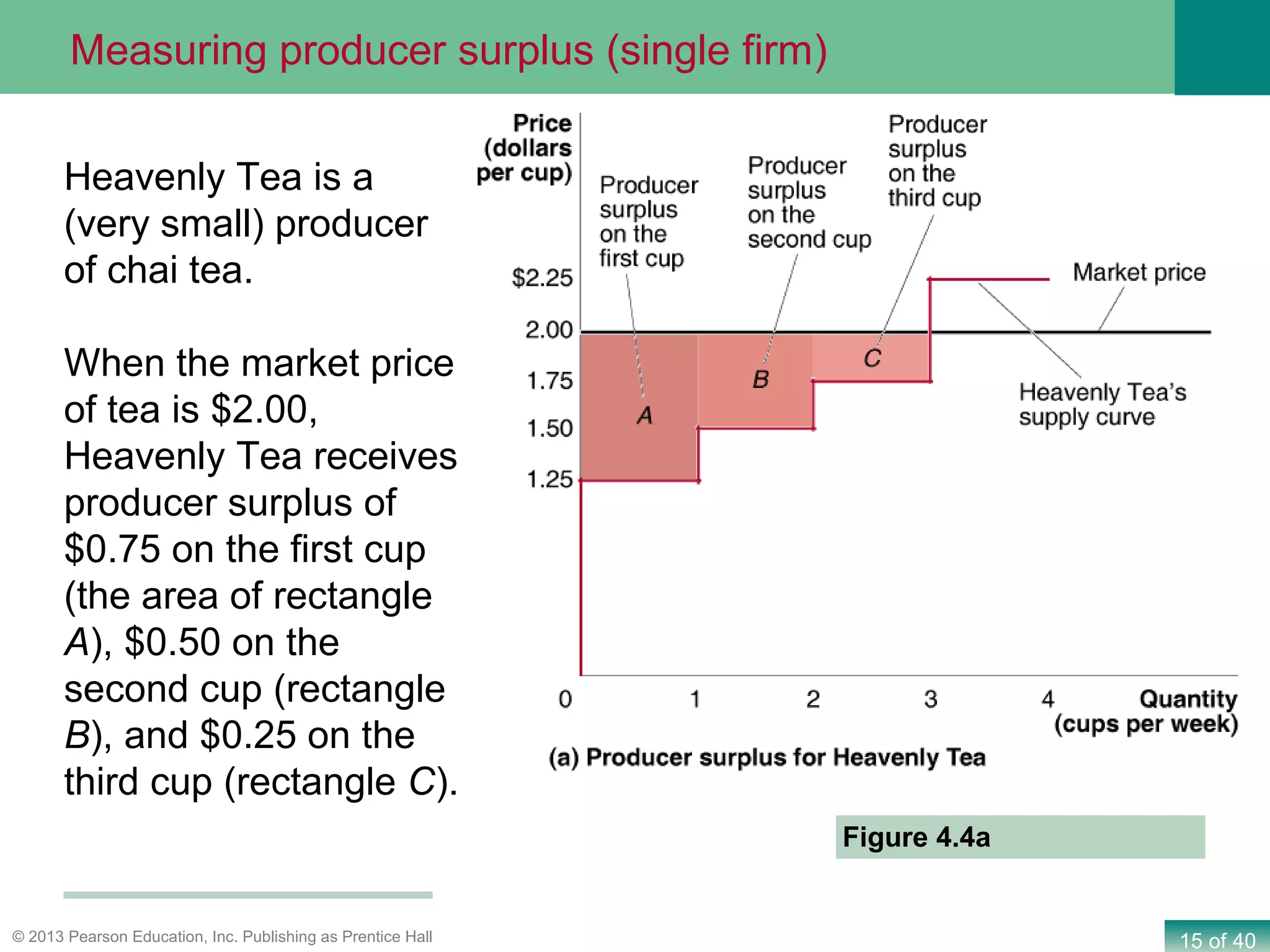

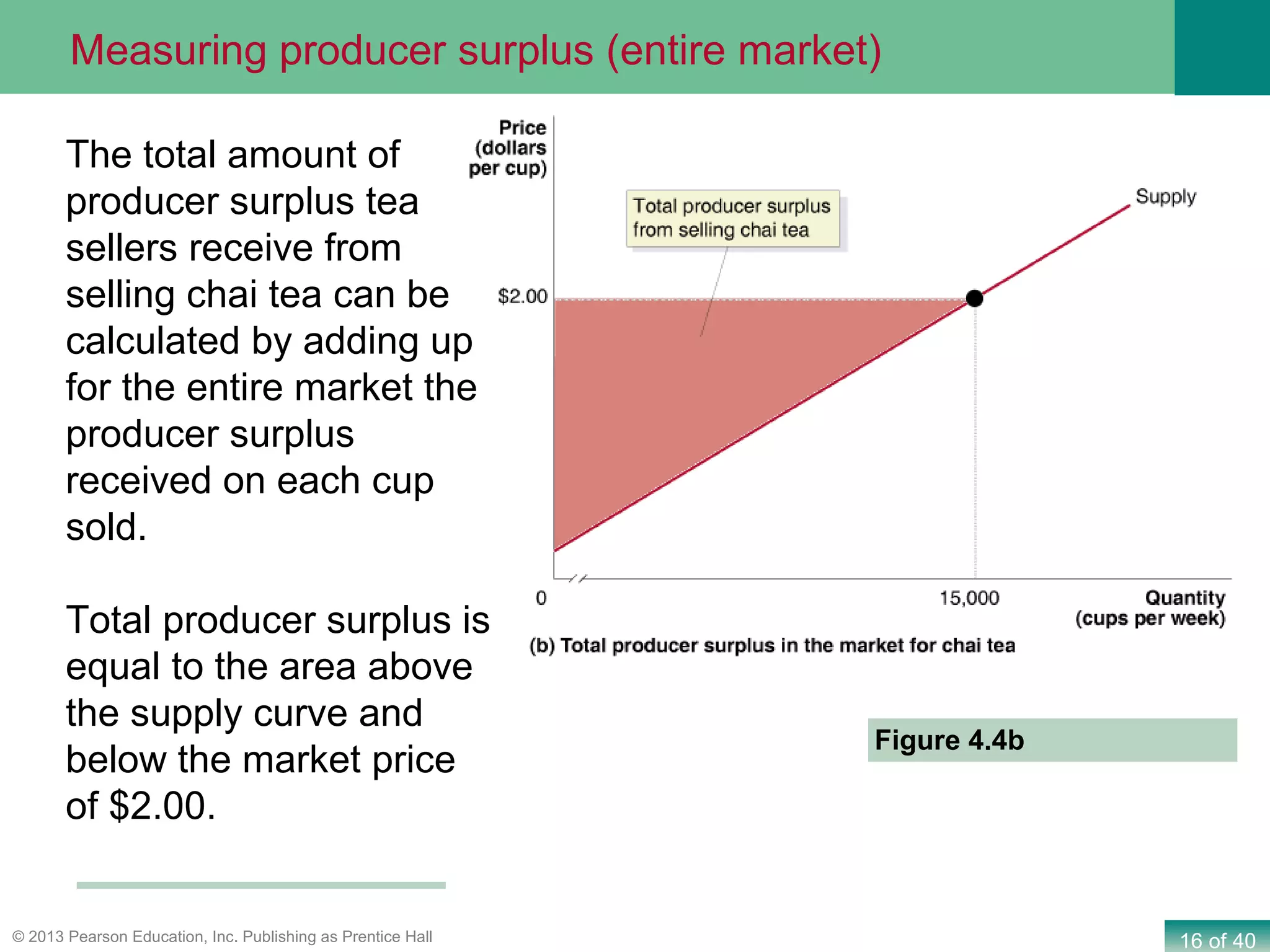

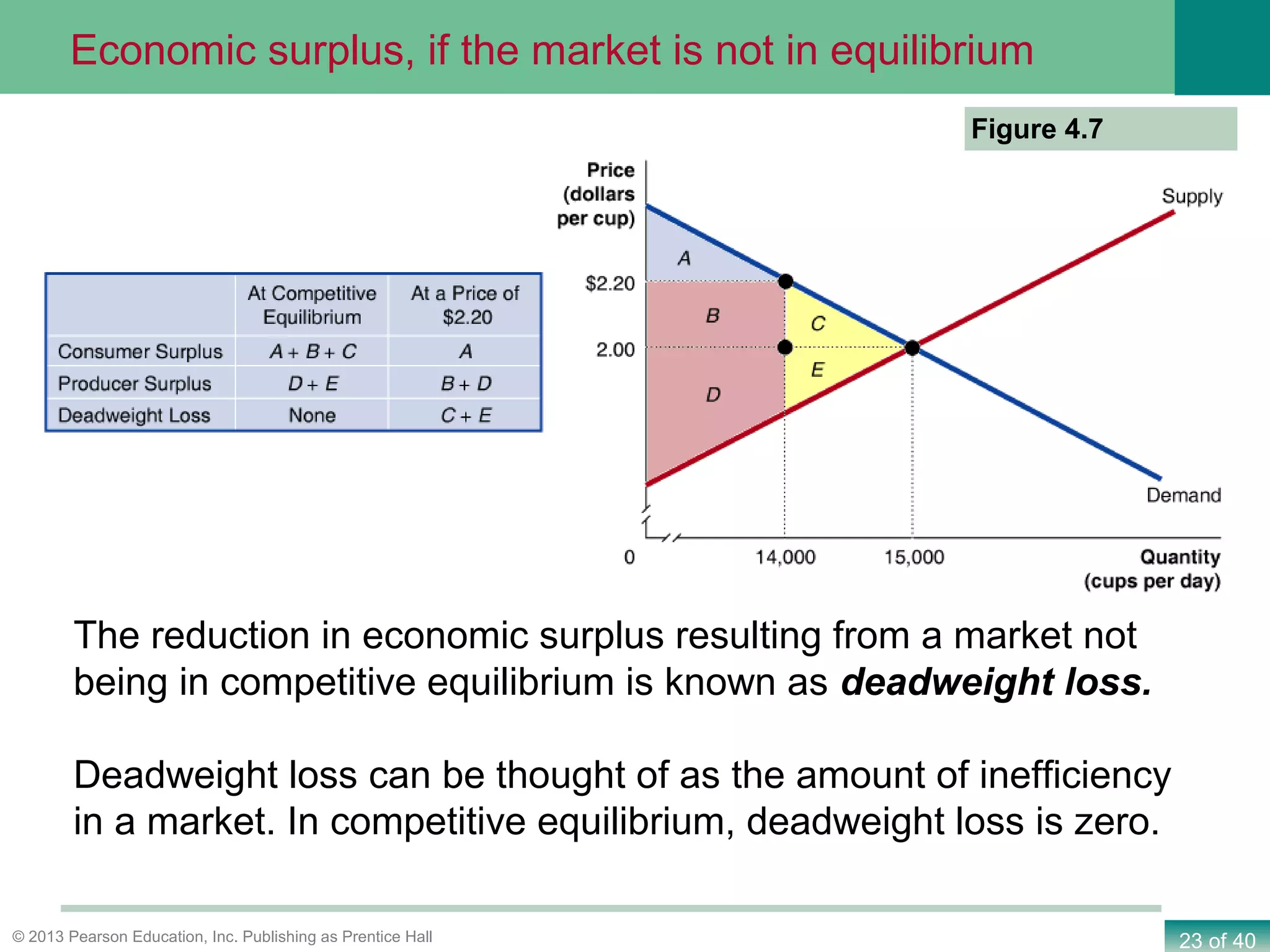

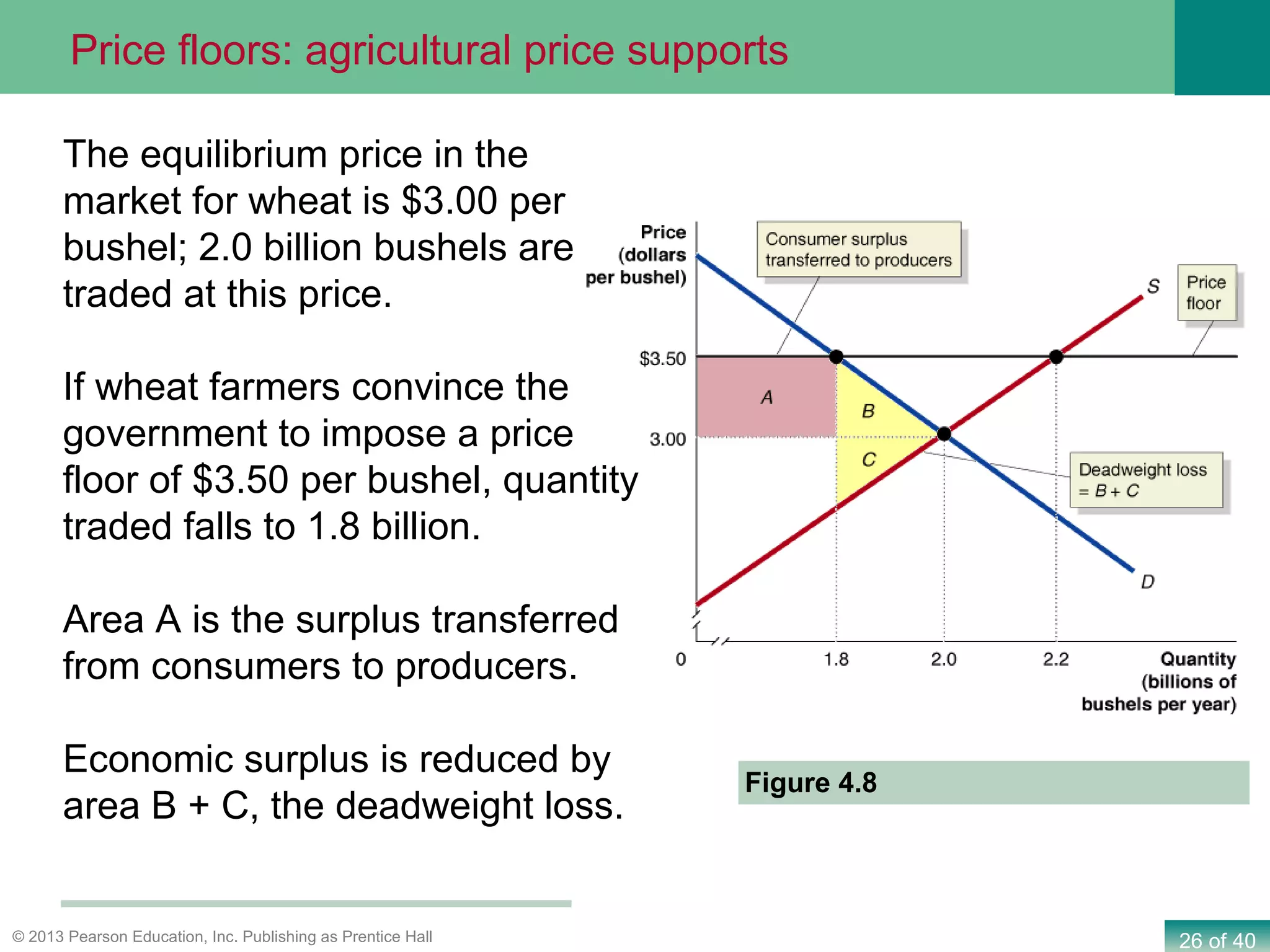

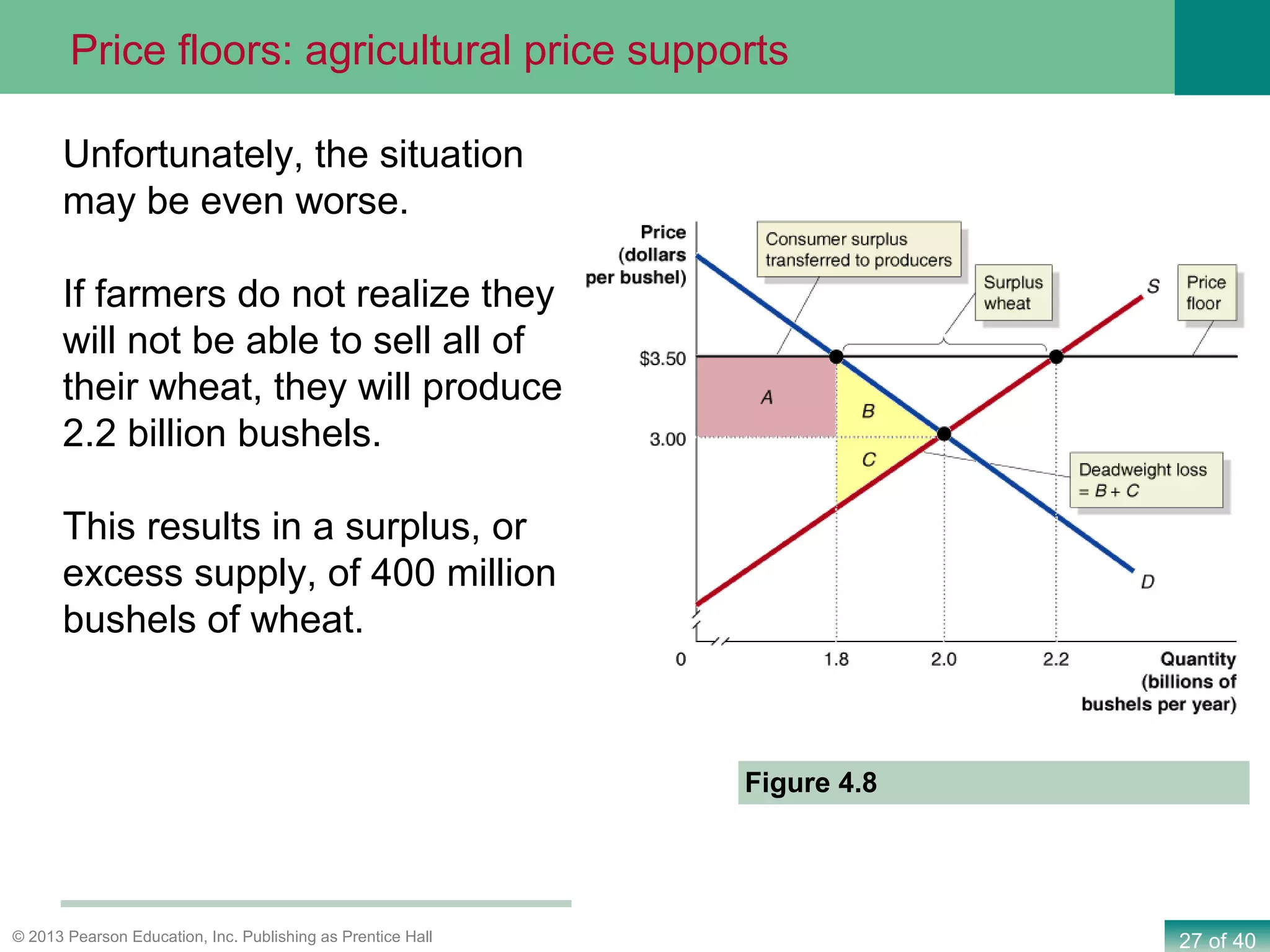

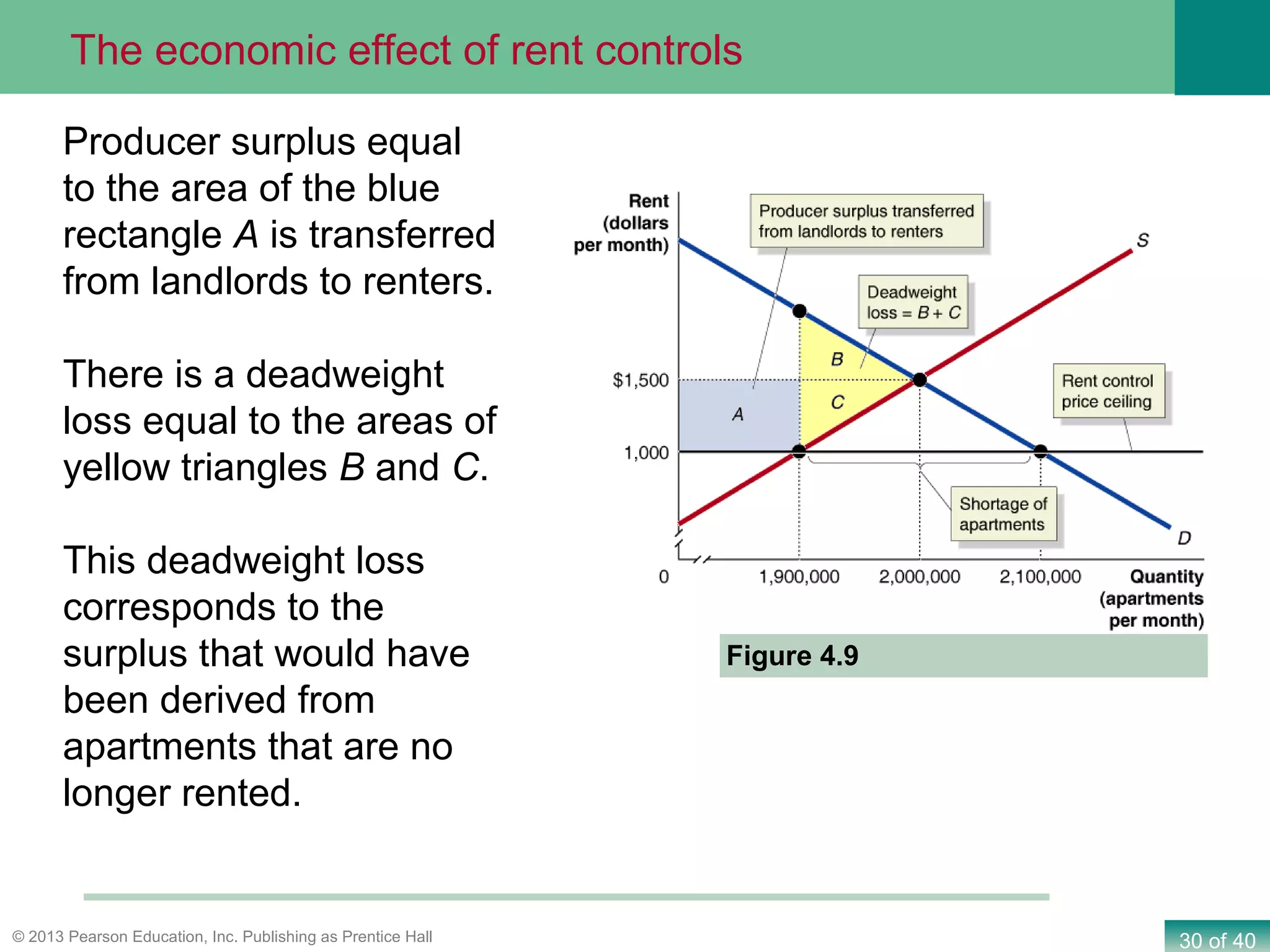

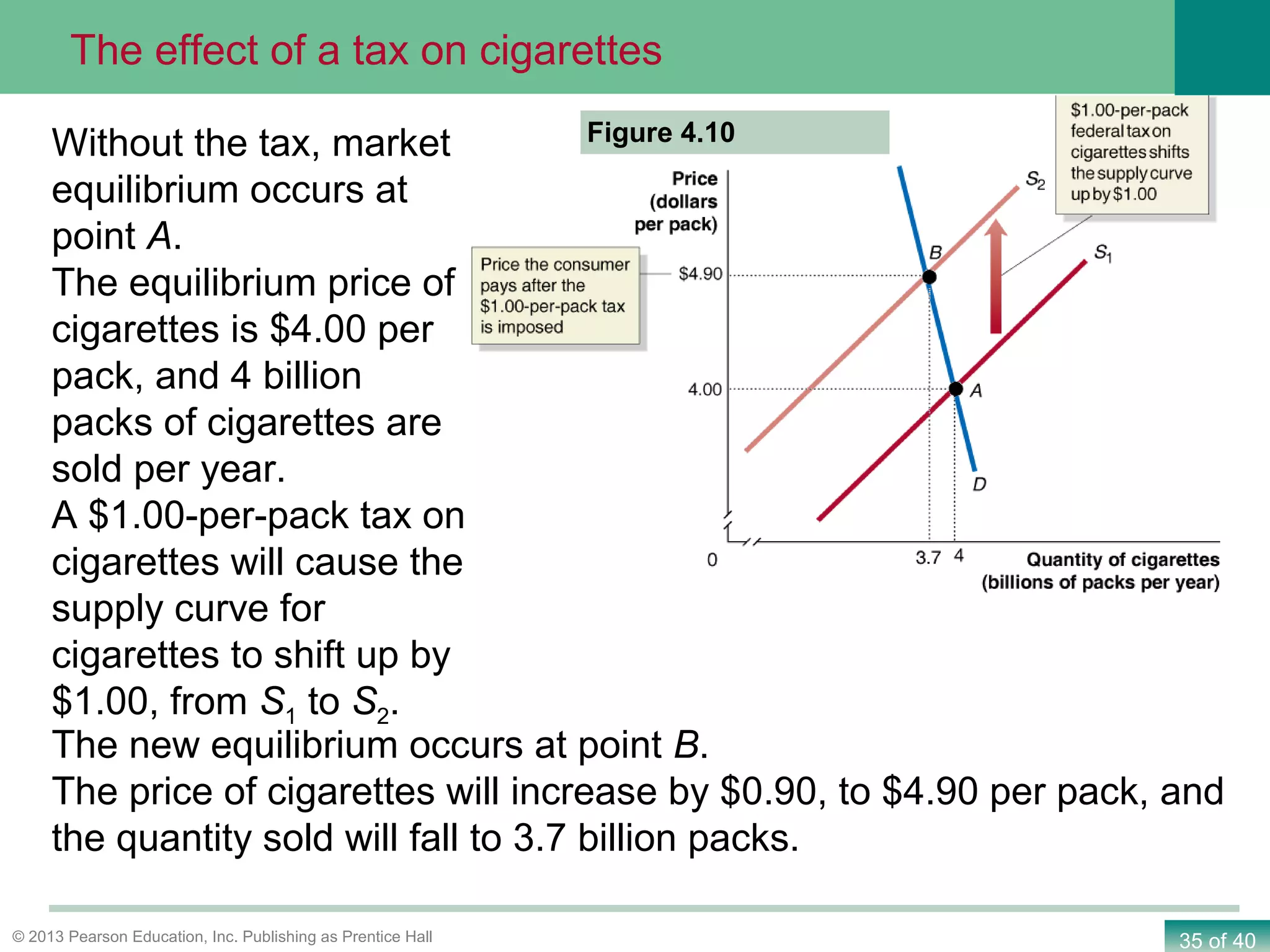

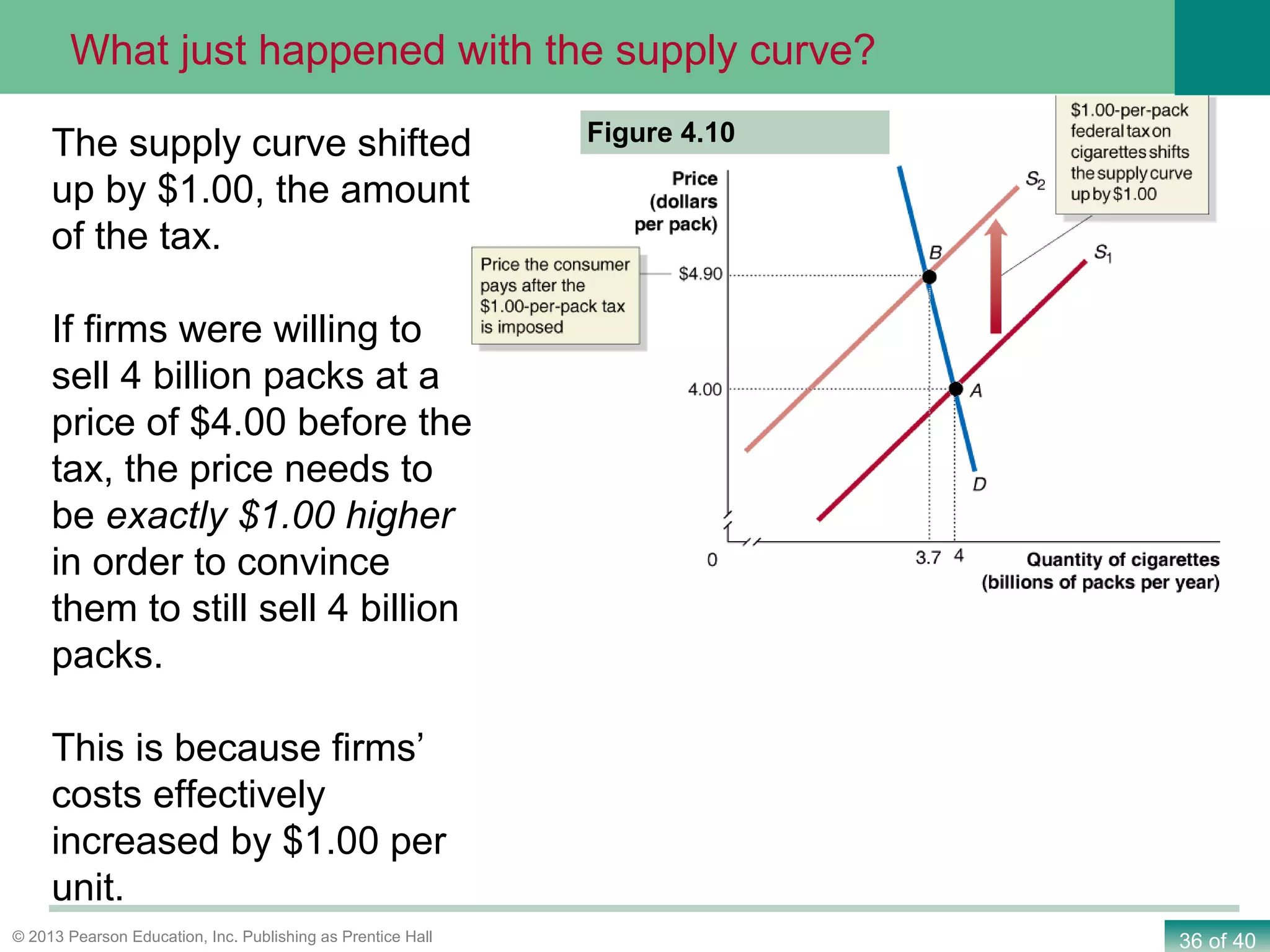

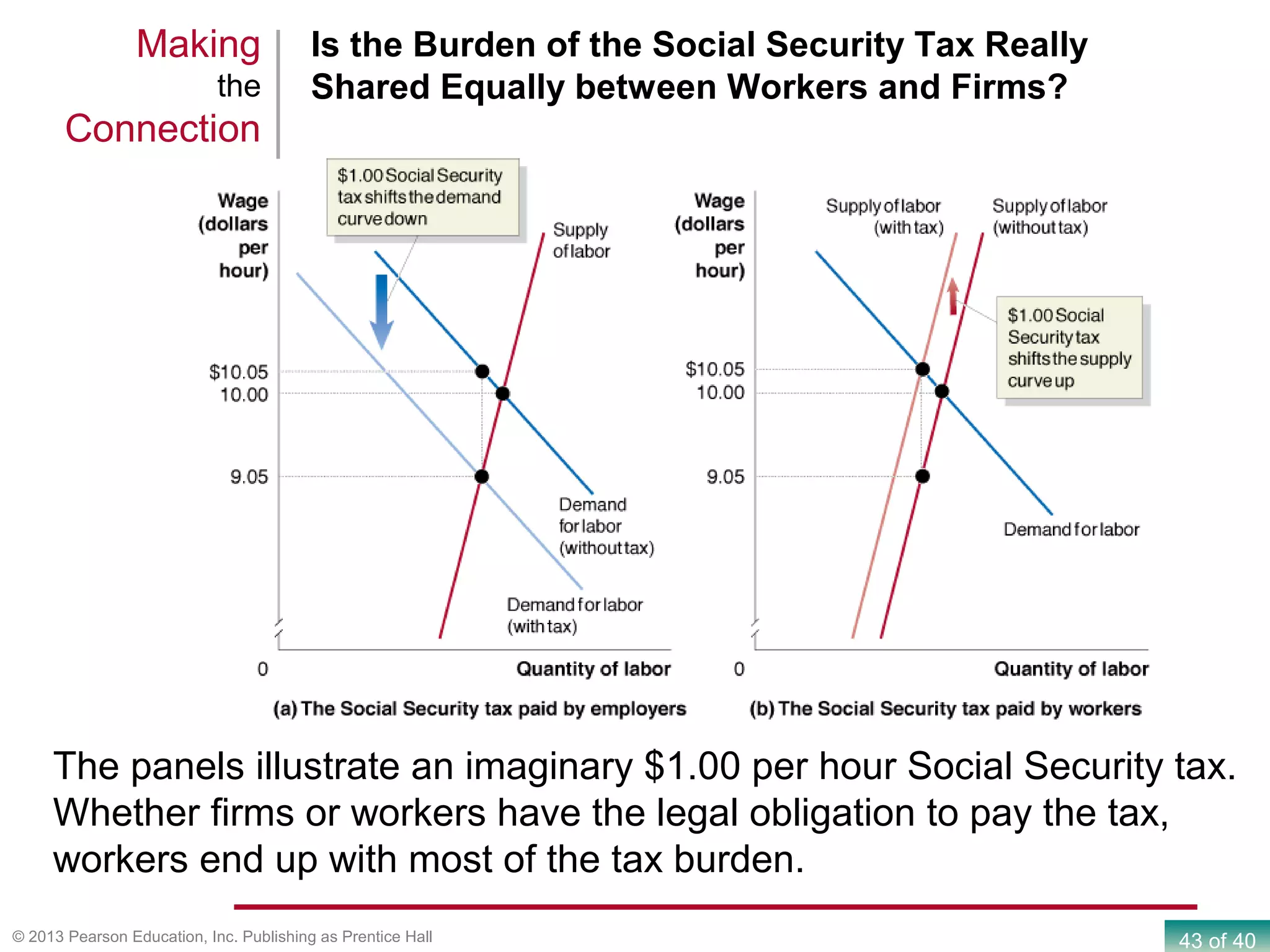

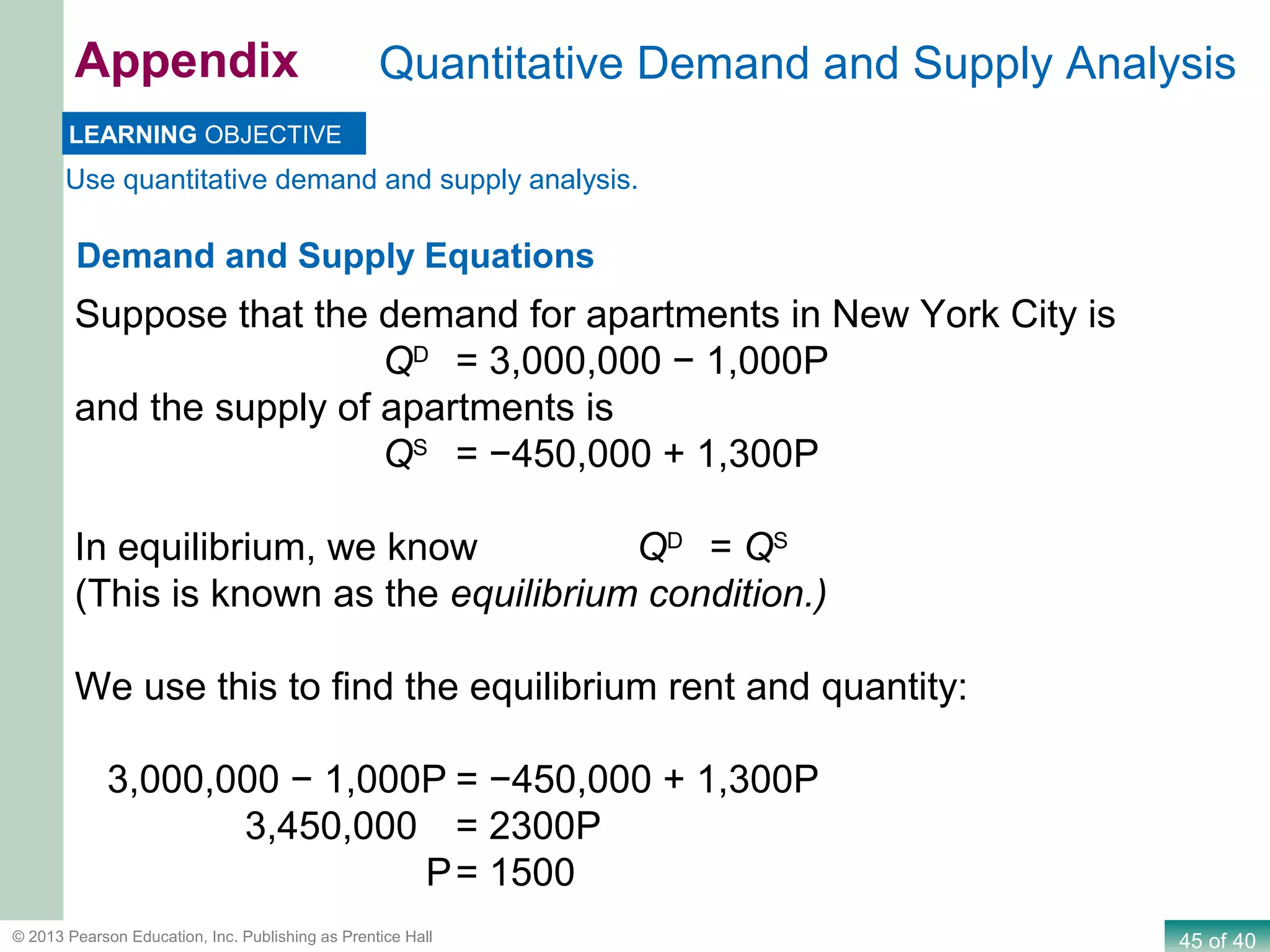

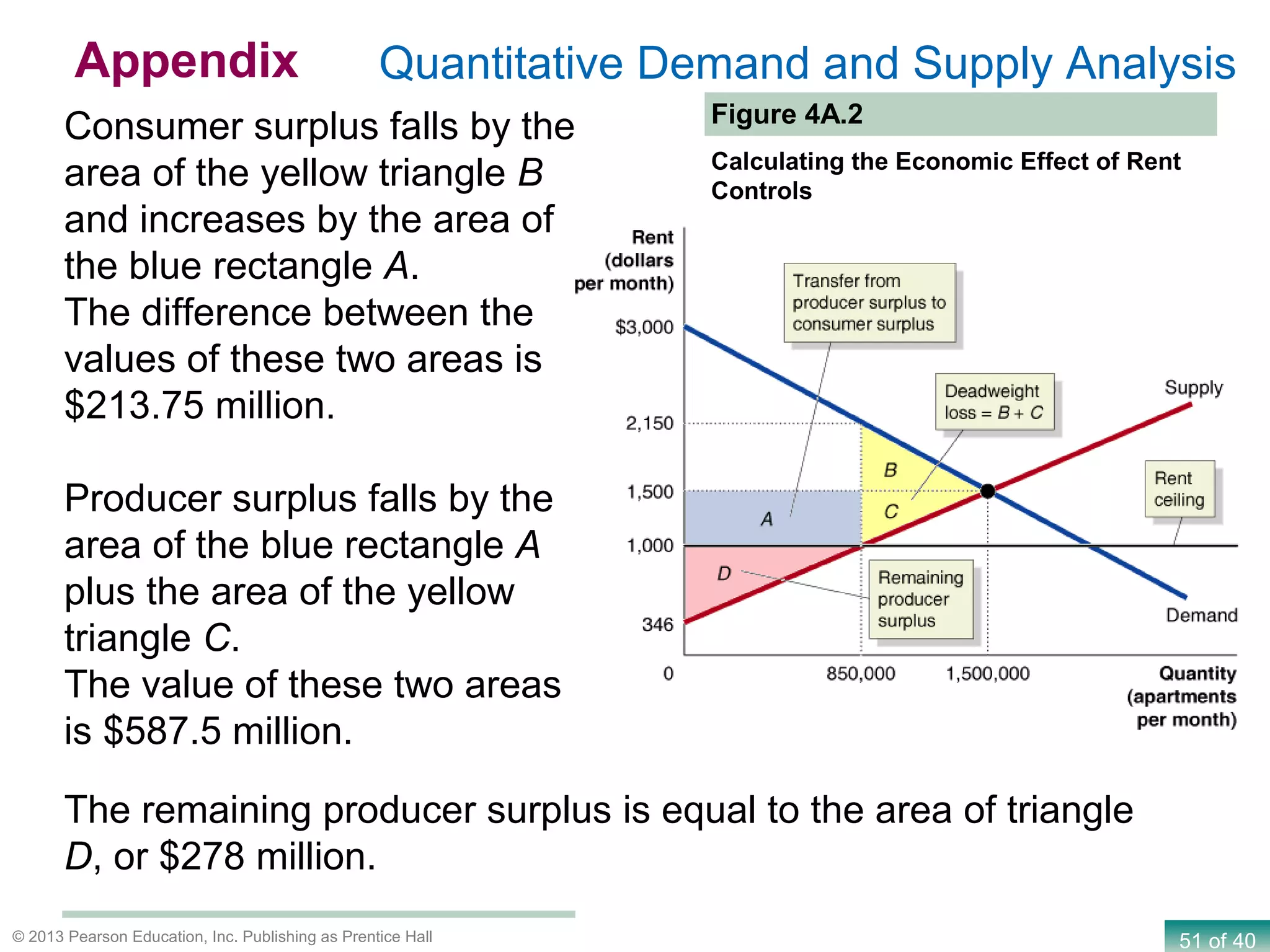

This document discusses key concepts from economics including consumer surplus, producer surplus, economic efficiency, and the impacts of government intervention in markets through price floors and ceilings. It provides learning objectives and outlines for a chapter that distinguishes consumer and producer surplus, explains how competitive markets achieve economic efficiency, and analyzes the economic effects of taxes. Various diagrams and examples are used to illustrate demand and supply, consumer and producer surplus, and the potential deadweight loss from price controls.