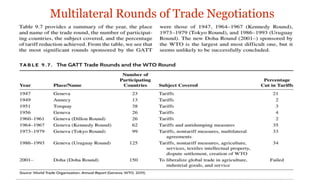

The document outlines the history and significance of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) and its multilateral trade negotiations, including key rounds such as the Kennedy, Tokyo, and Uruguay rounds, which led to tariff reductions and the establishment of the World Trade Organization (WTO). It also addresses the challenges faced during the Doha Round and current global trade issues such as protectionism, high agricultural subsidies, and the risks of trade wars. Overall, it highlights both the accomplishments and persistent problems in international trade since the inception of GATT.