This document provides an overview and summary of the book "Fundamentals of Plastics Mould Design". The book covers fundamentals of product design, injection mould design, compression mould design, transfer mould design, blow mould design, extrusion dies design, and applications of CAD/CAM in mould design. It is intended to meet the requirements of engineering courses in plastics/polymer technology. The book includes concepts of mould design, plastic materials and processing, as well as recent technologies like CAD/CAM applications. It contains 550 questions and examples to illustrate design calculations.

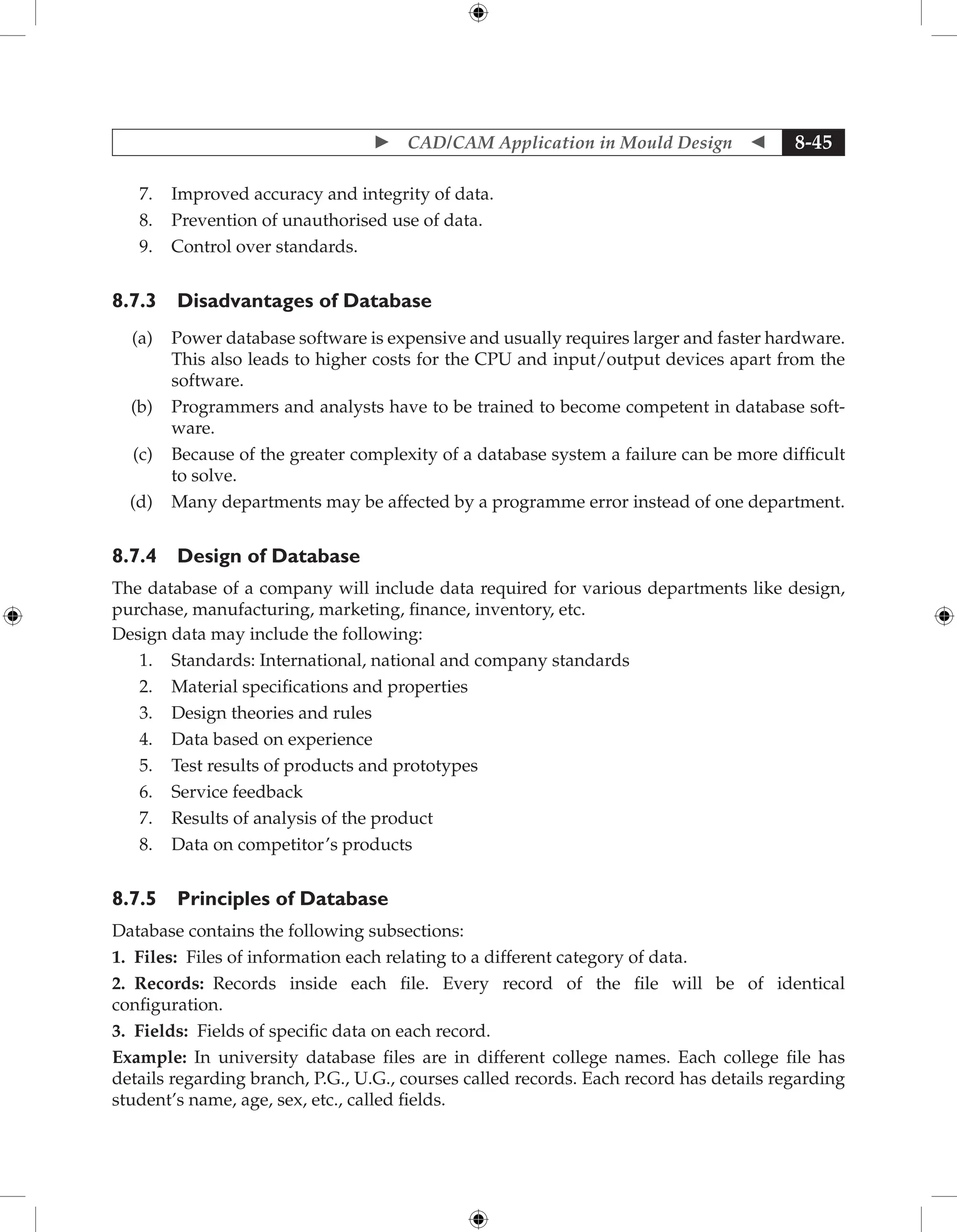

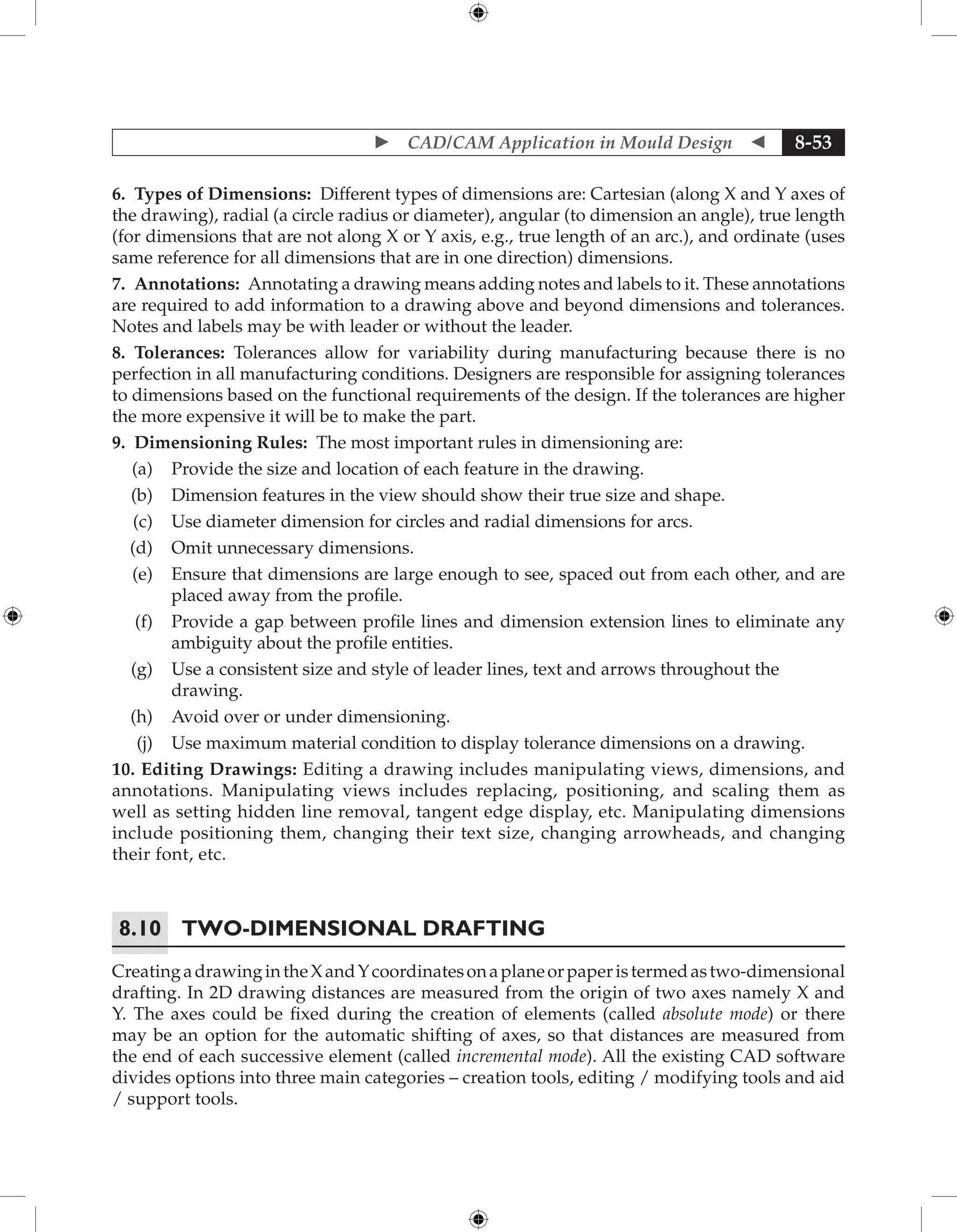

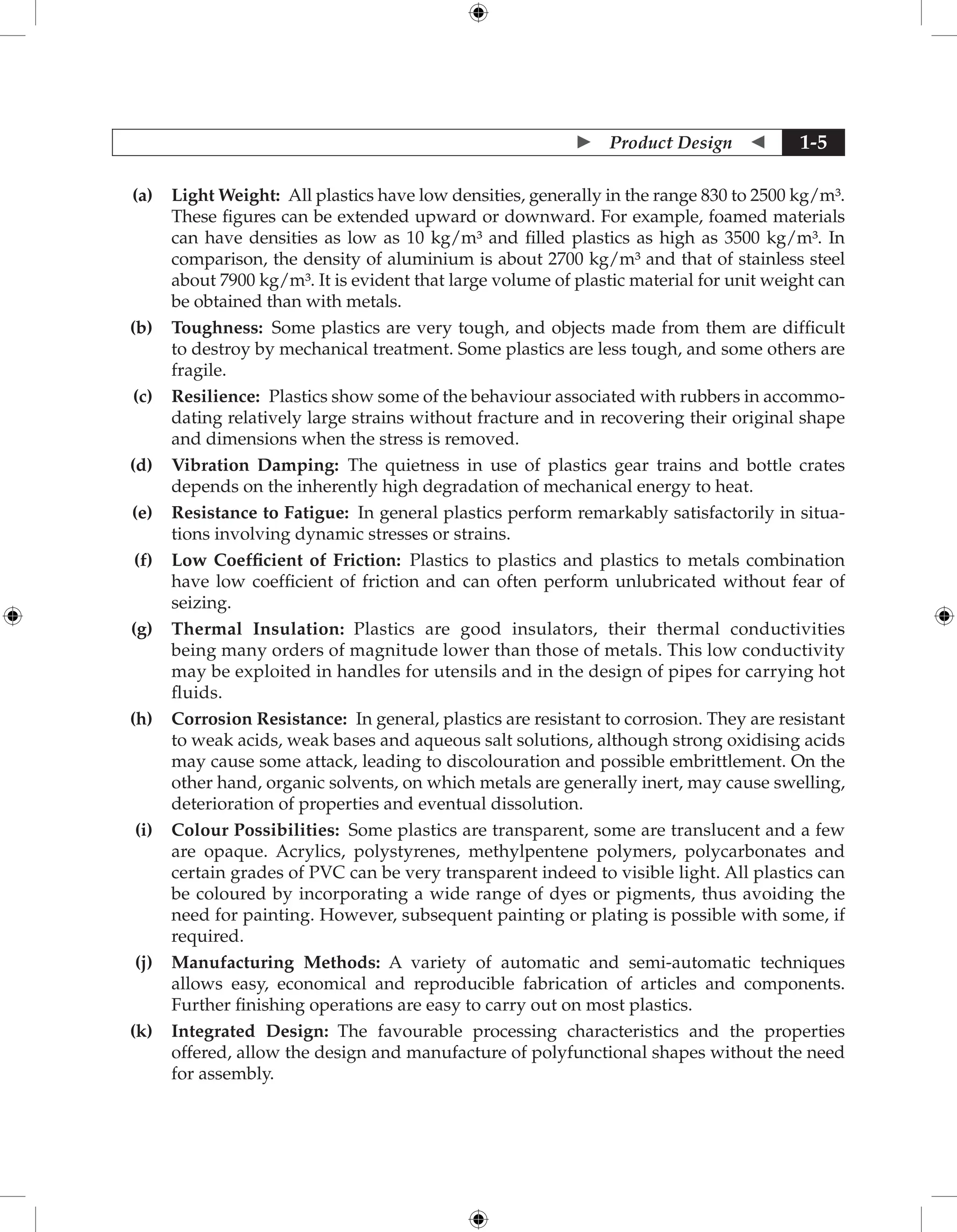

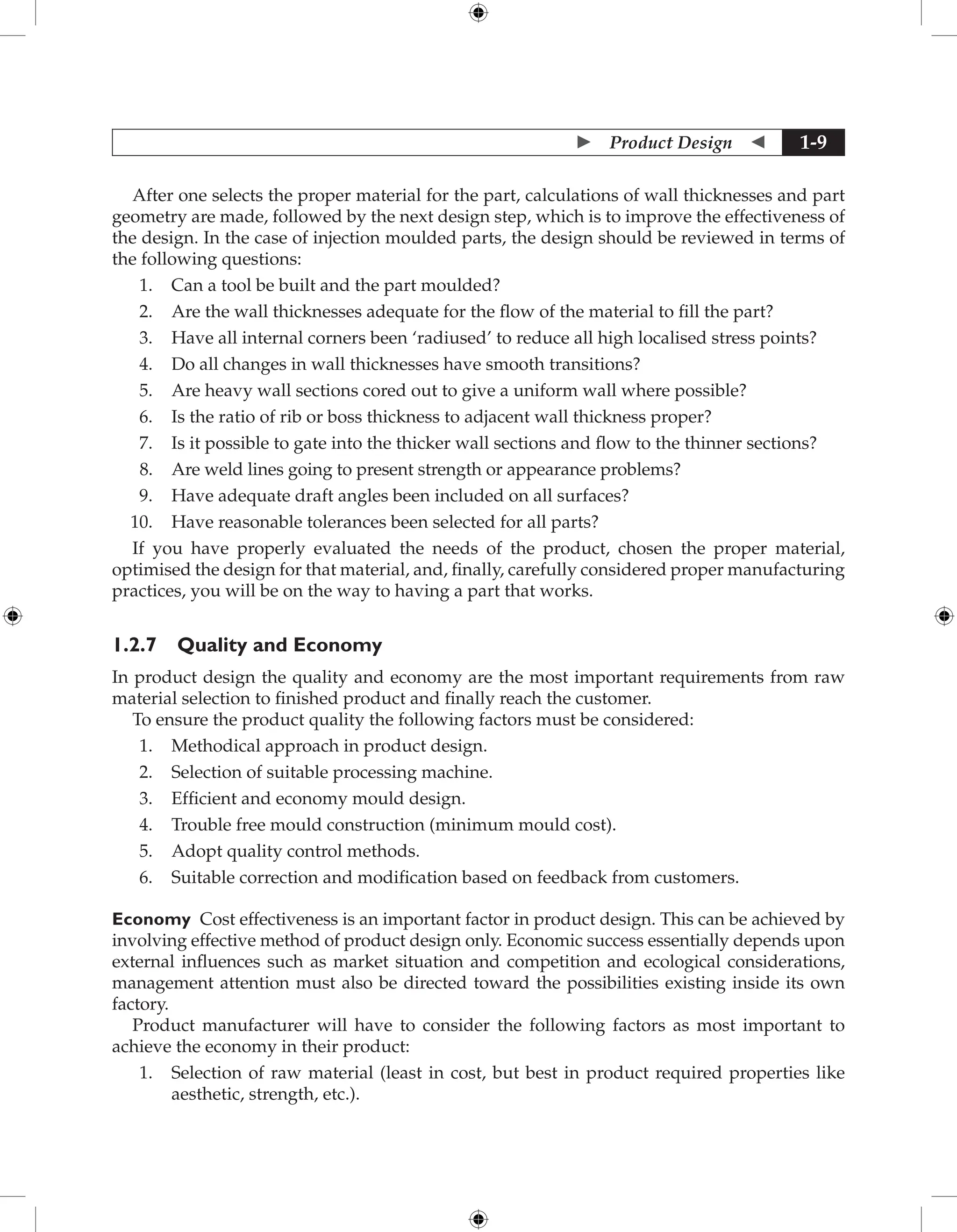

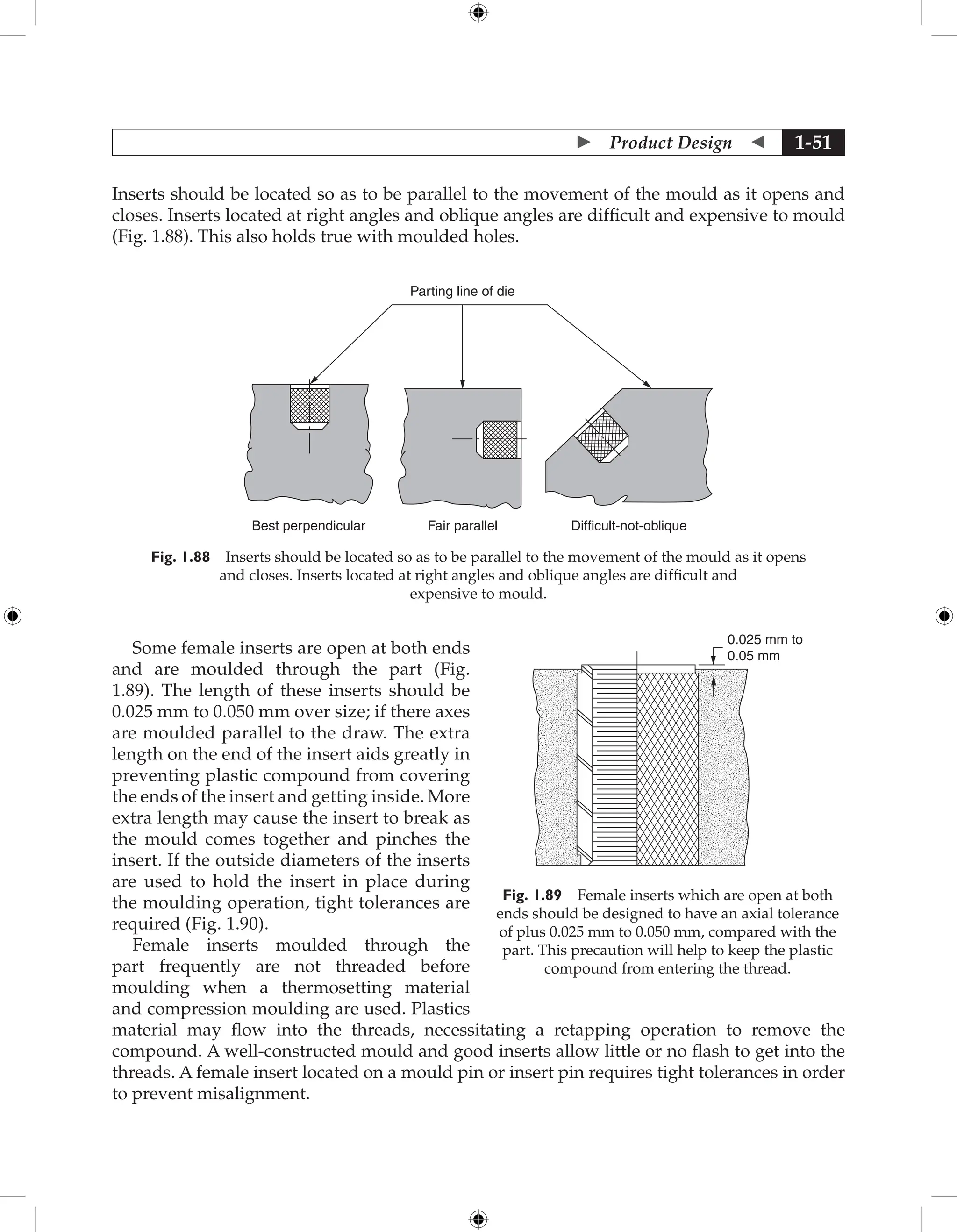

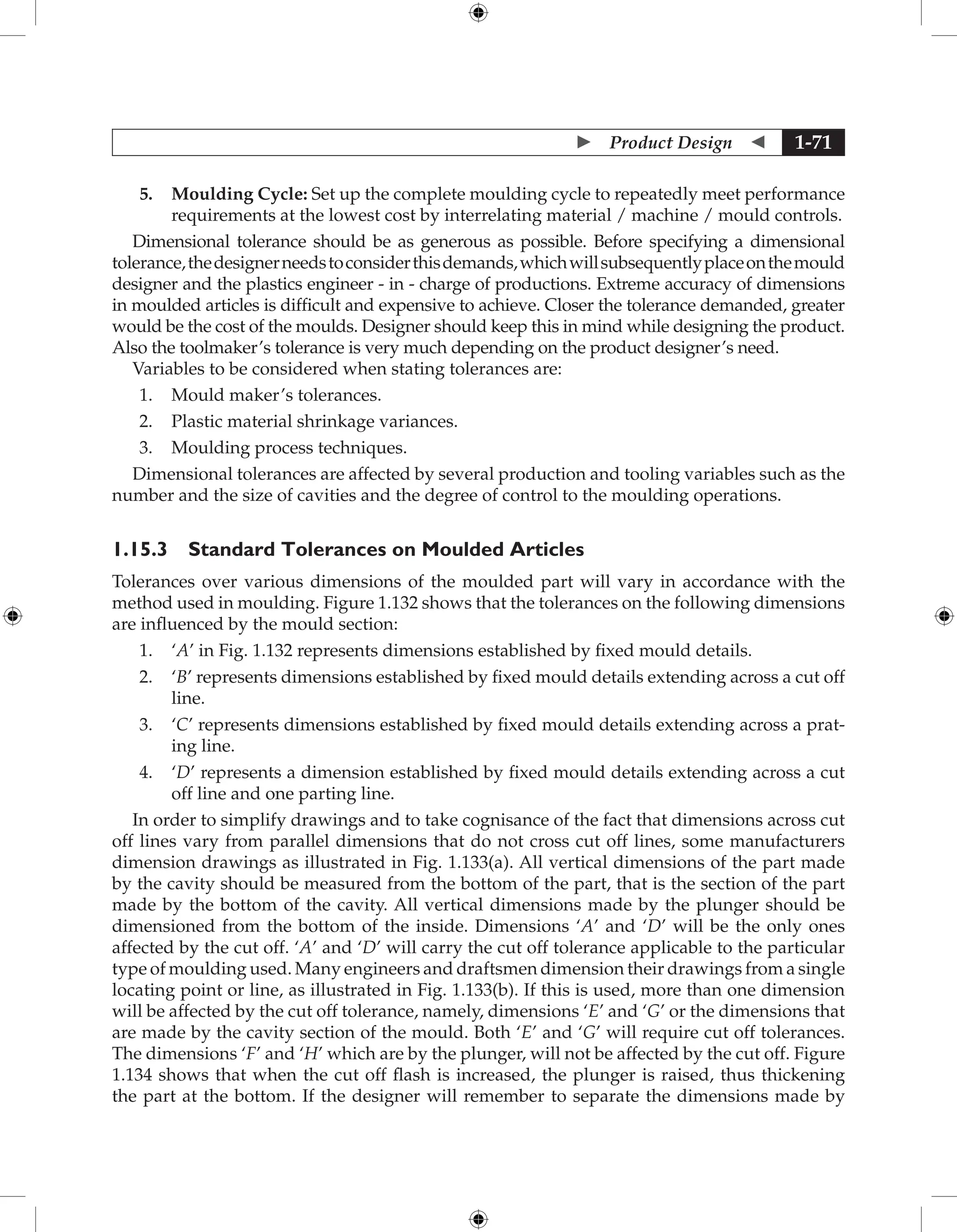

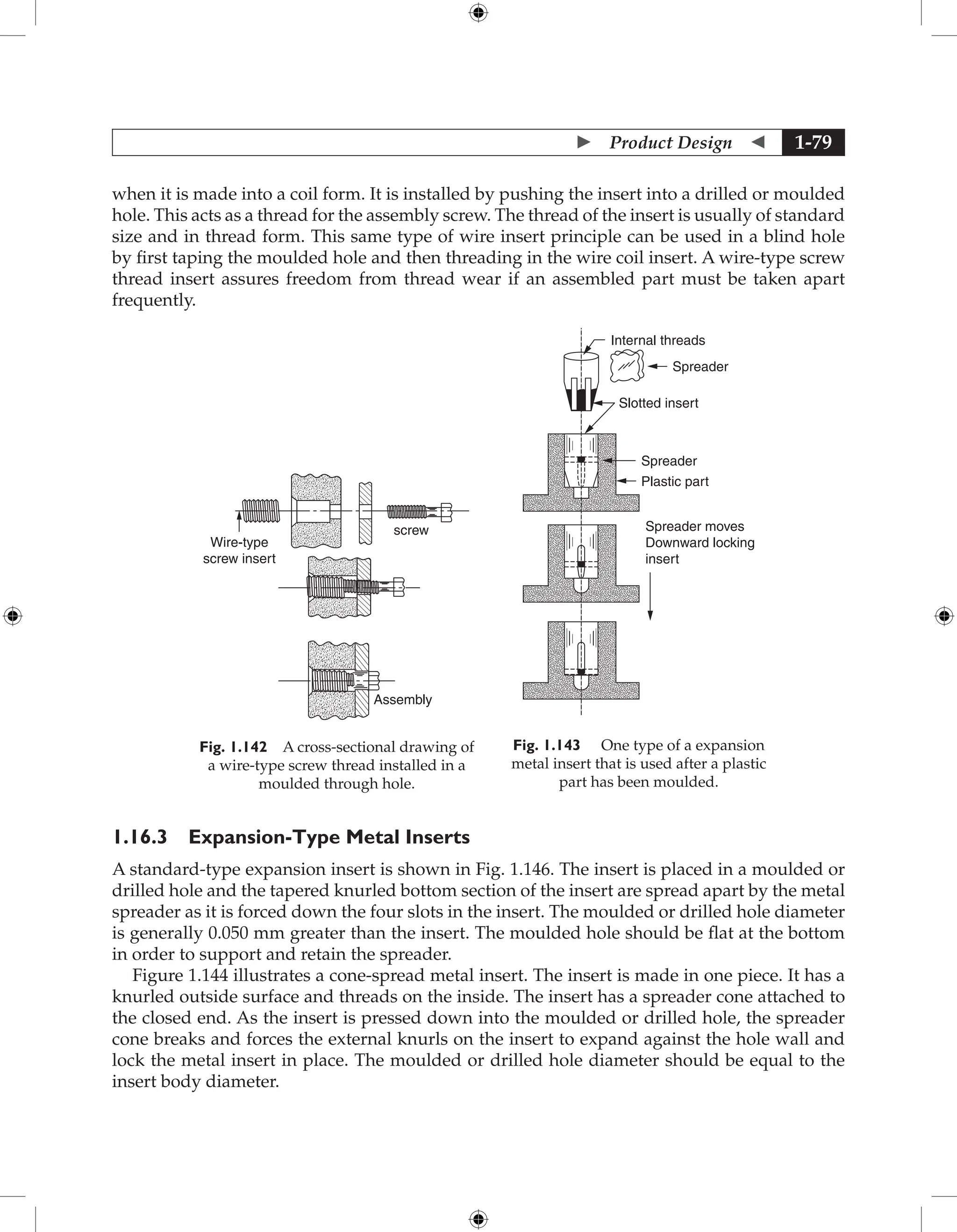

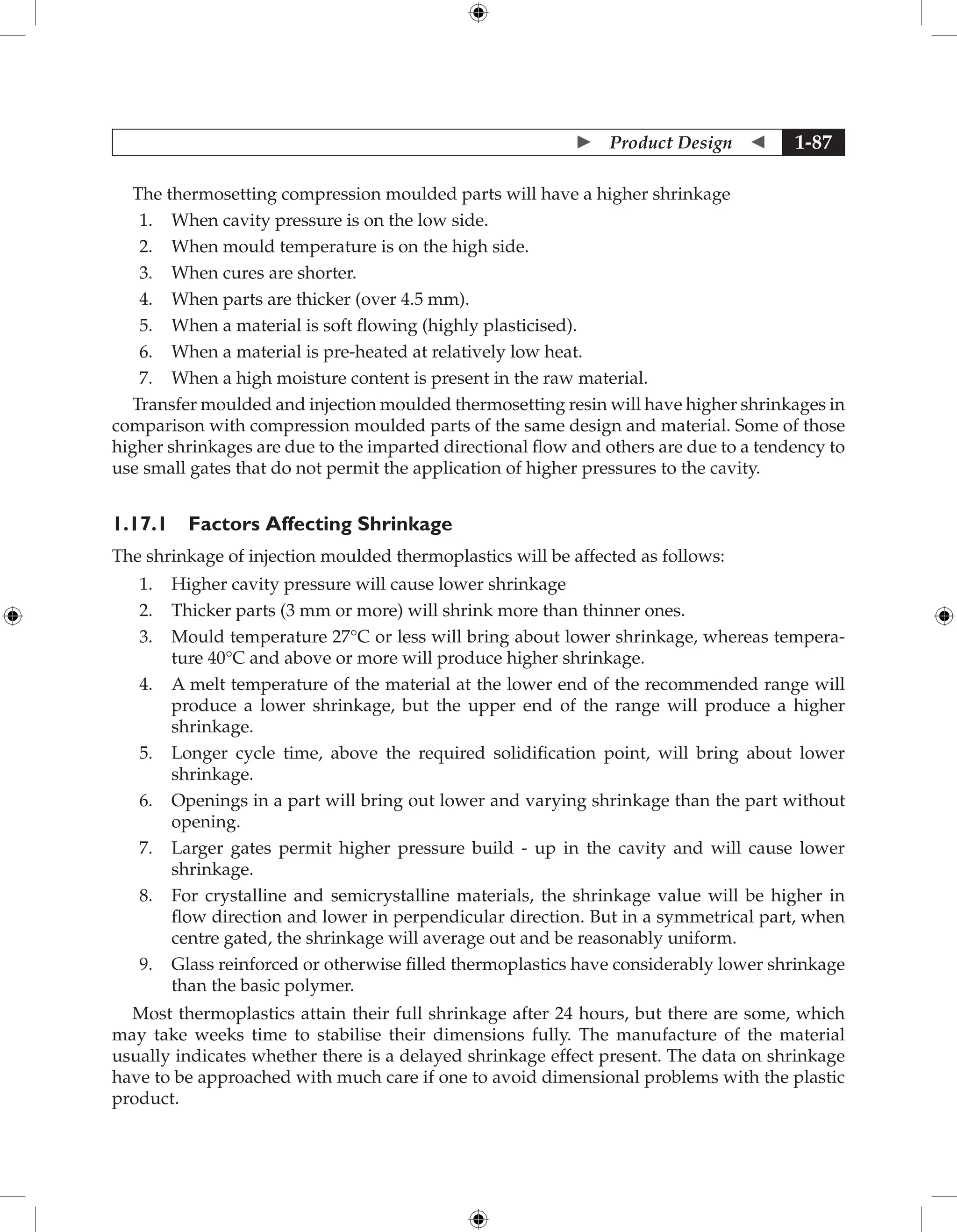

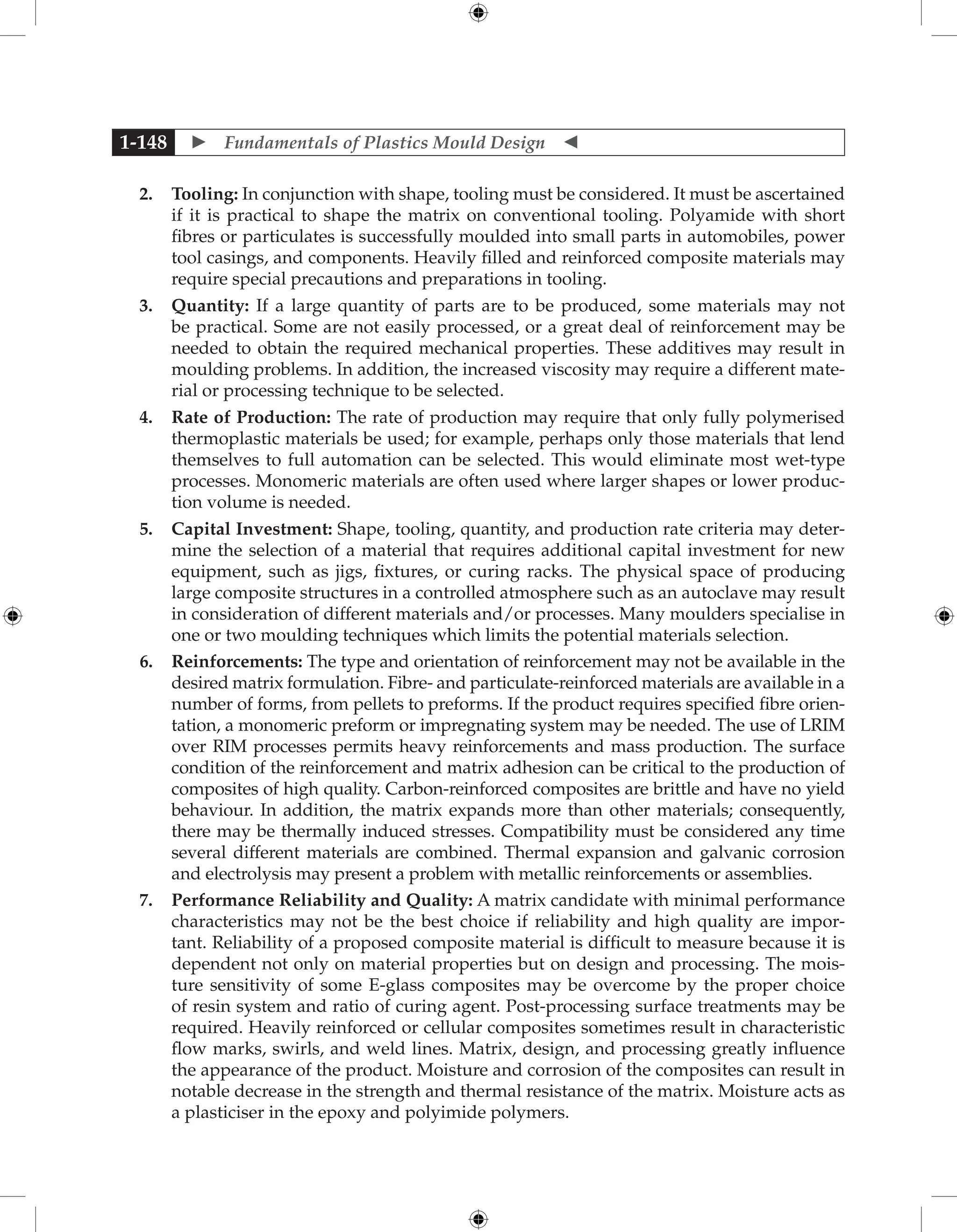

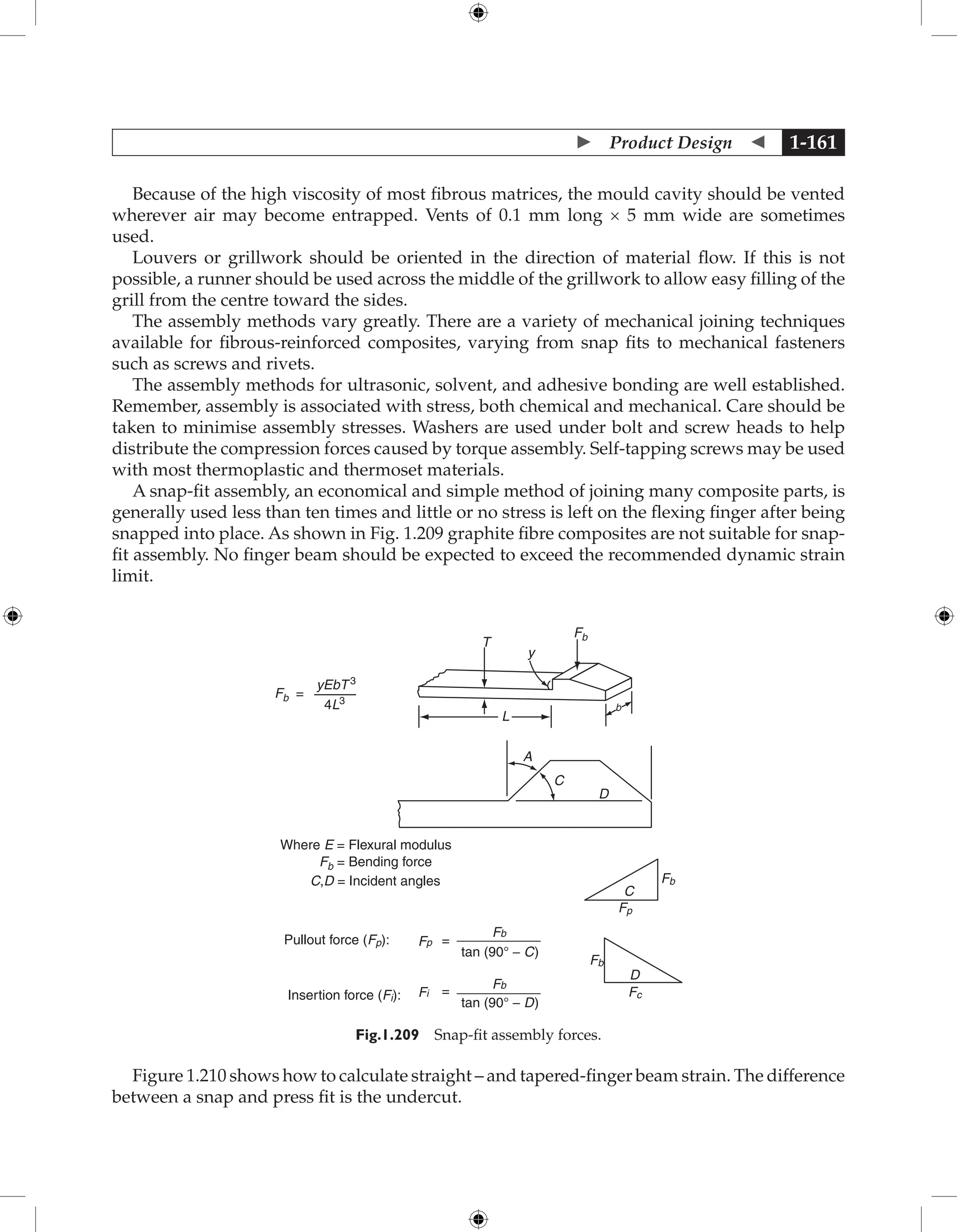

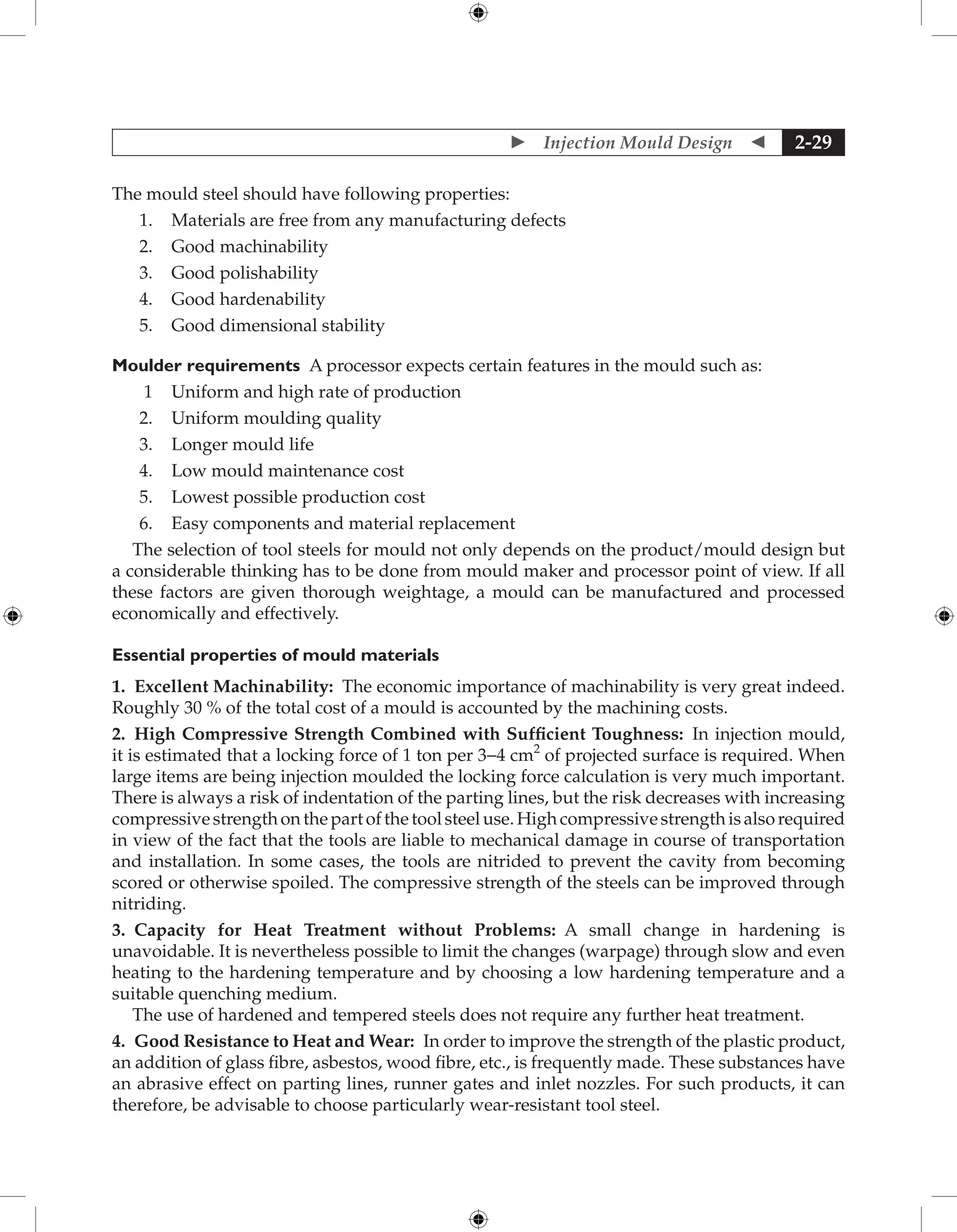

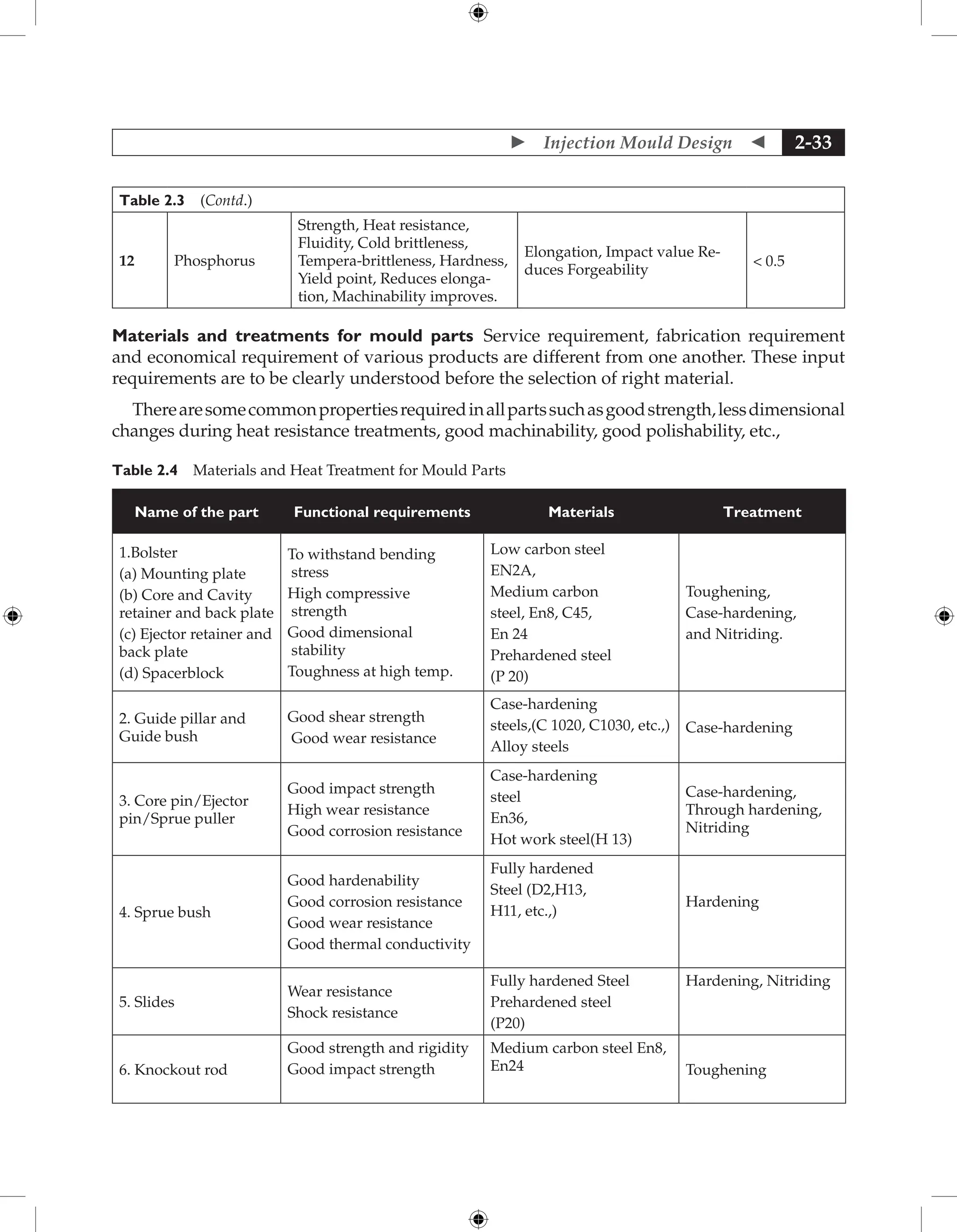

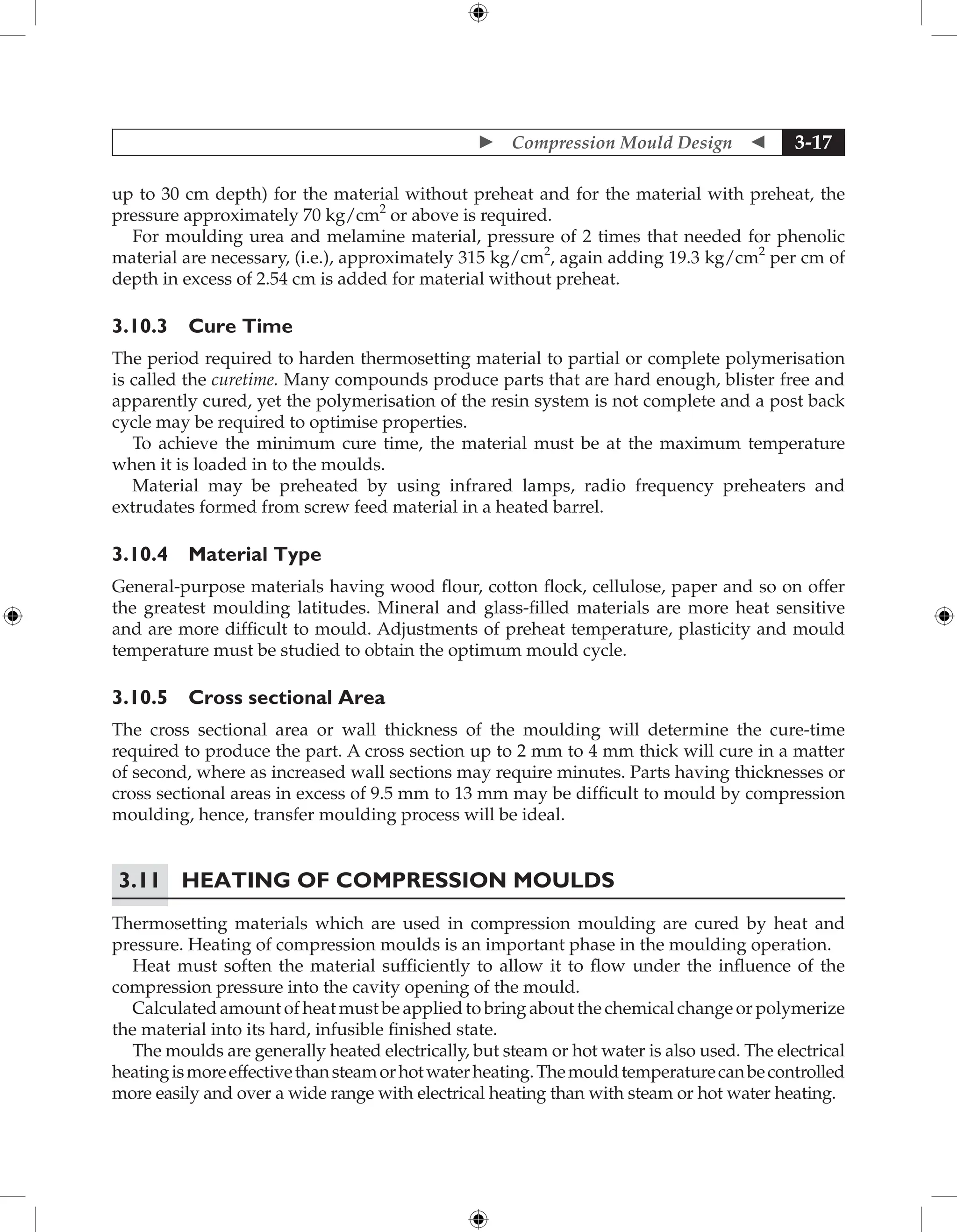

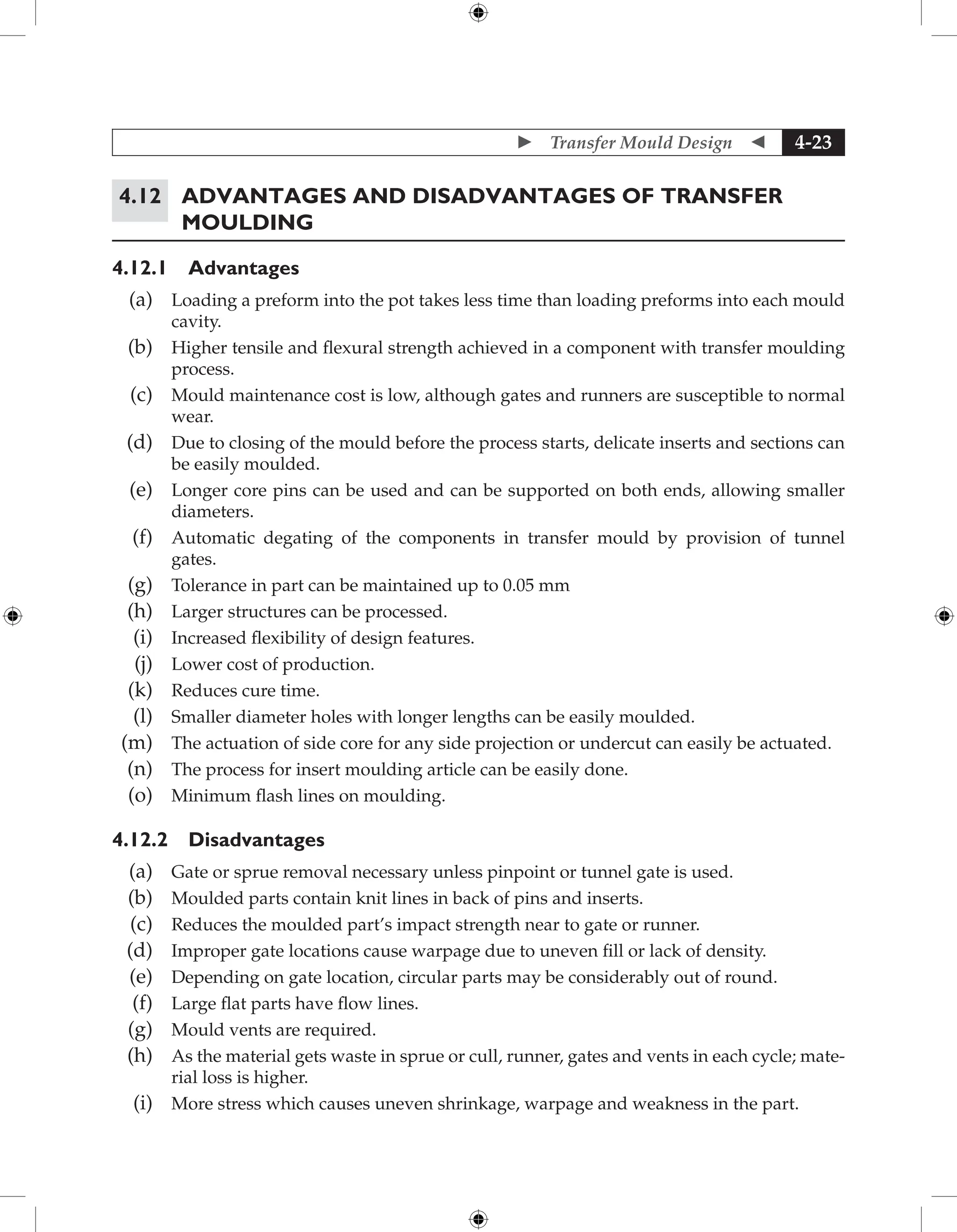

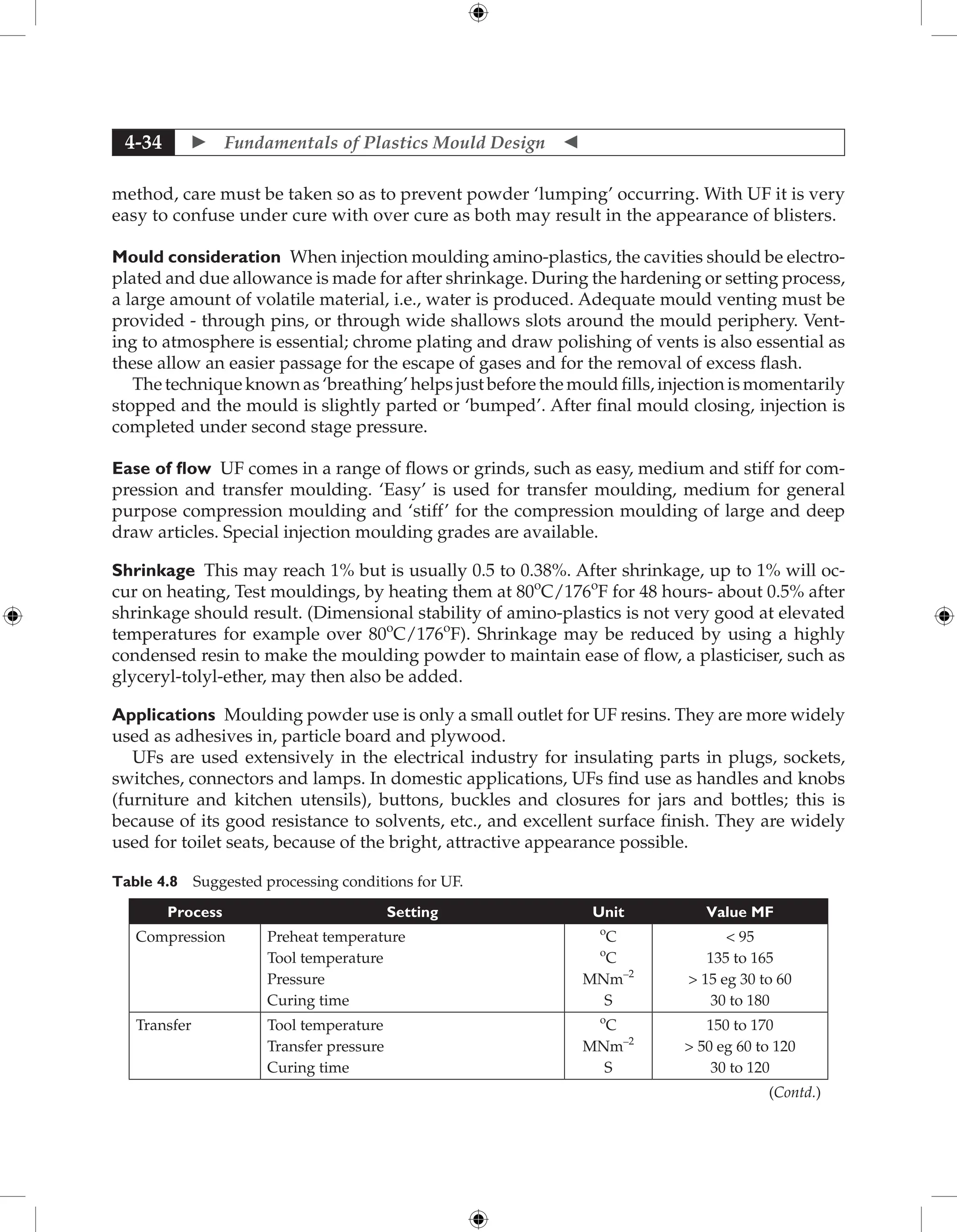

![ Product Design 1-101

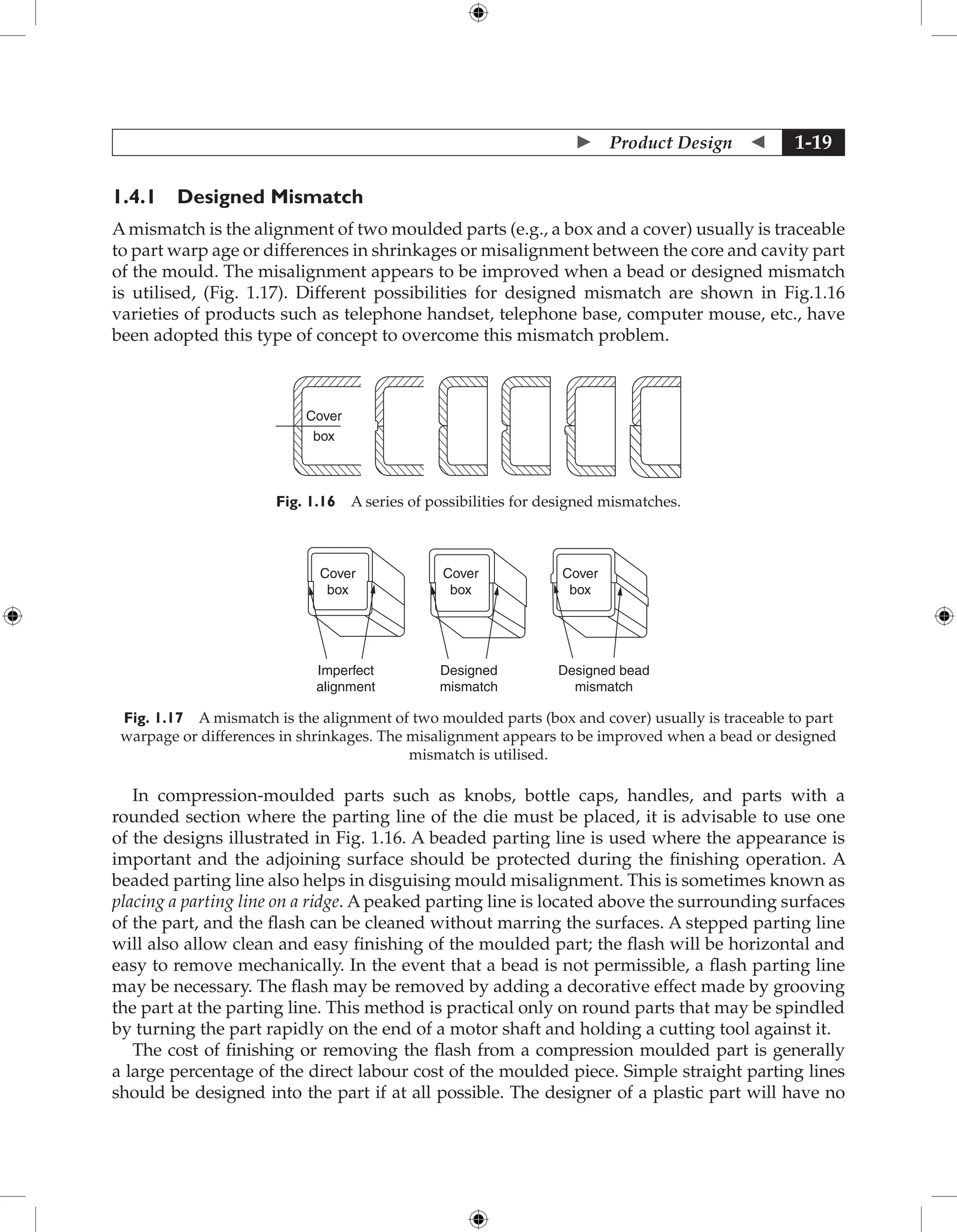

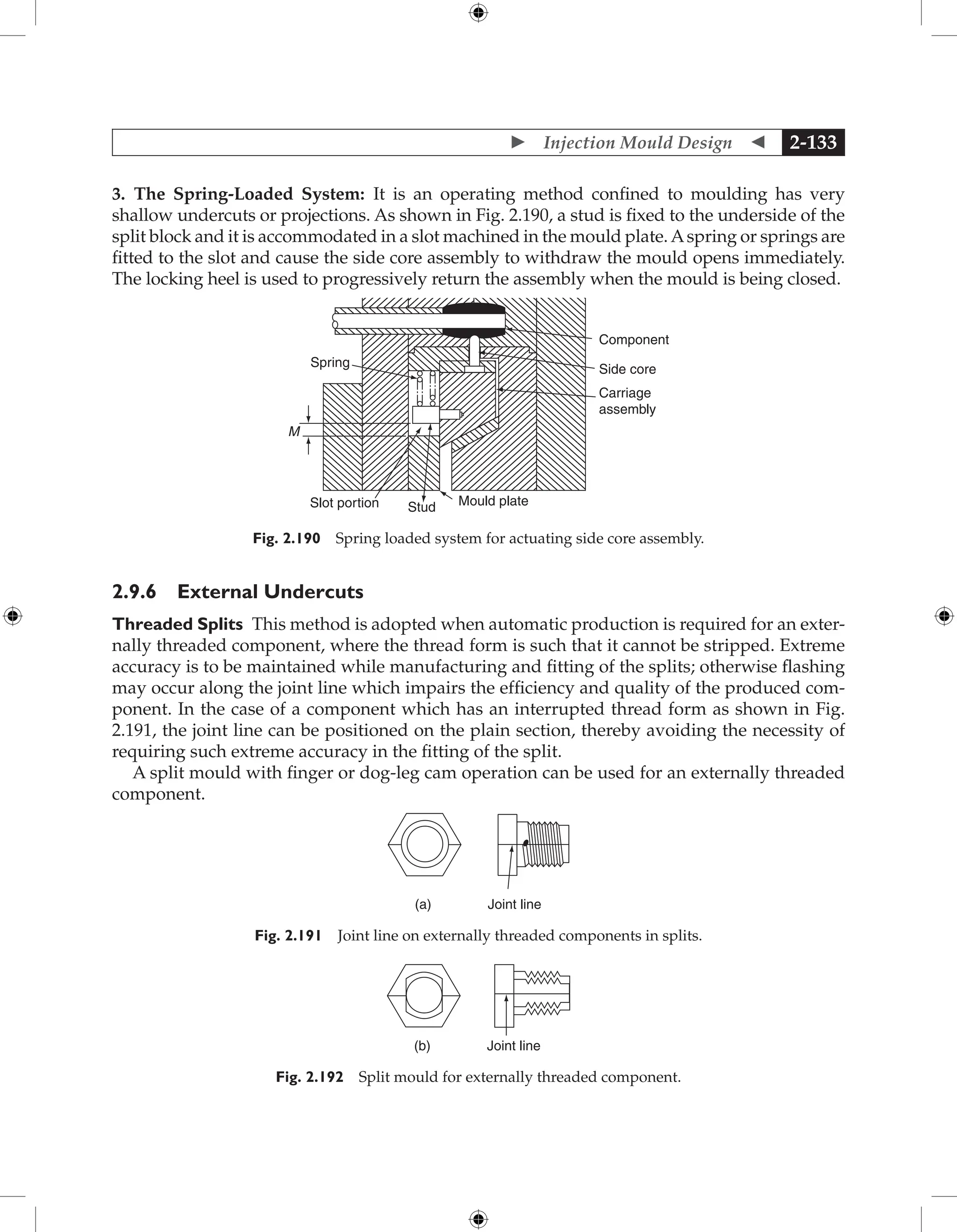

CYCLES TO FAILURE

12 PITCH

0

105

106

107

108

50

100

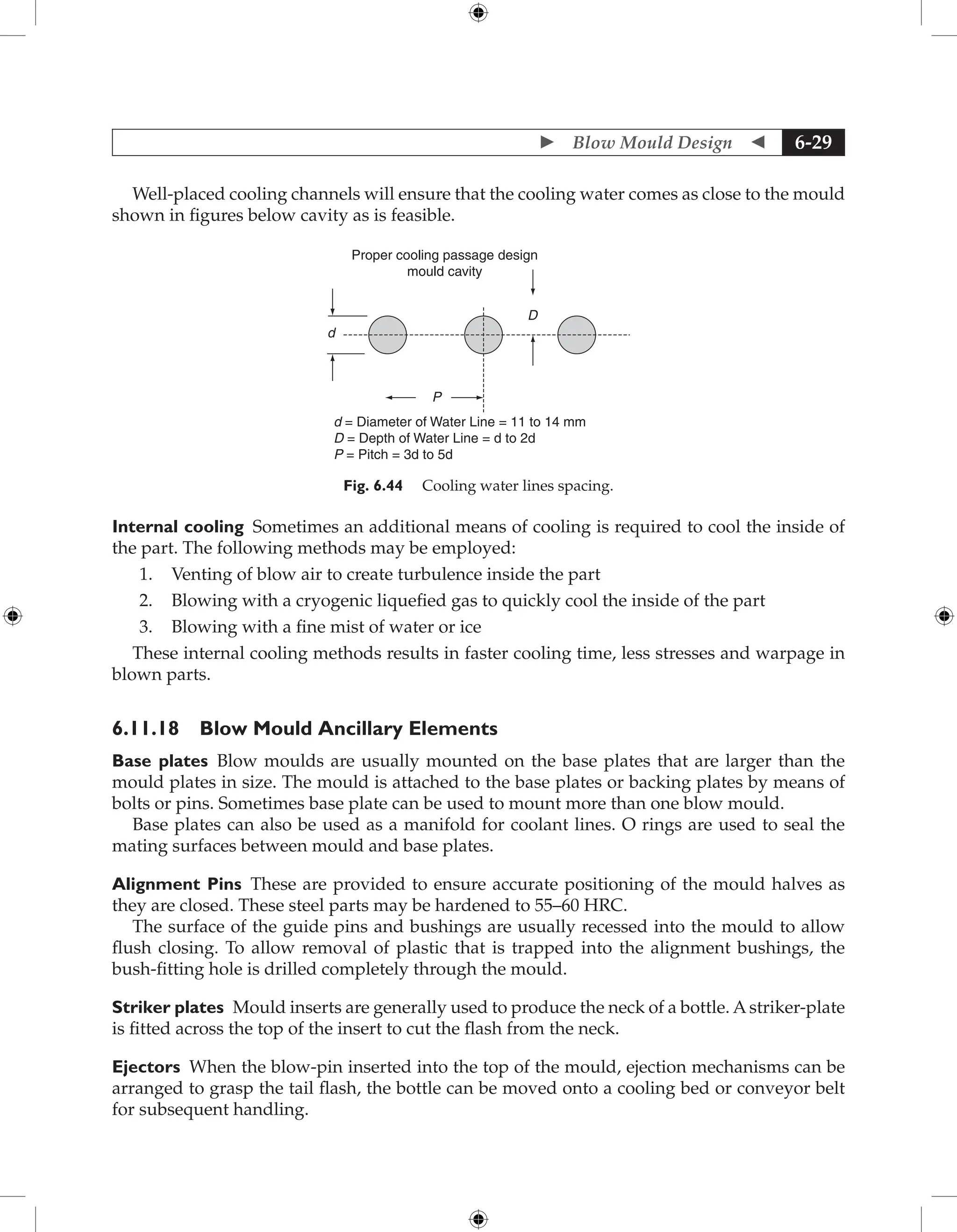

150

200

250

300

12 PITCH

4650 PLV

2750 PLV

2750 PLV

32 and 24 PITCH

20° pressure angle

73 F ambient temp.

celcon M90

APPLIED

UNIT

LOAD

(Lu)

LBS/IN

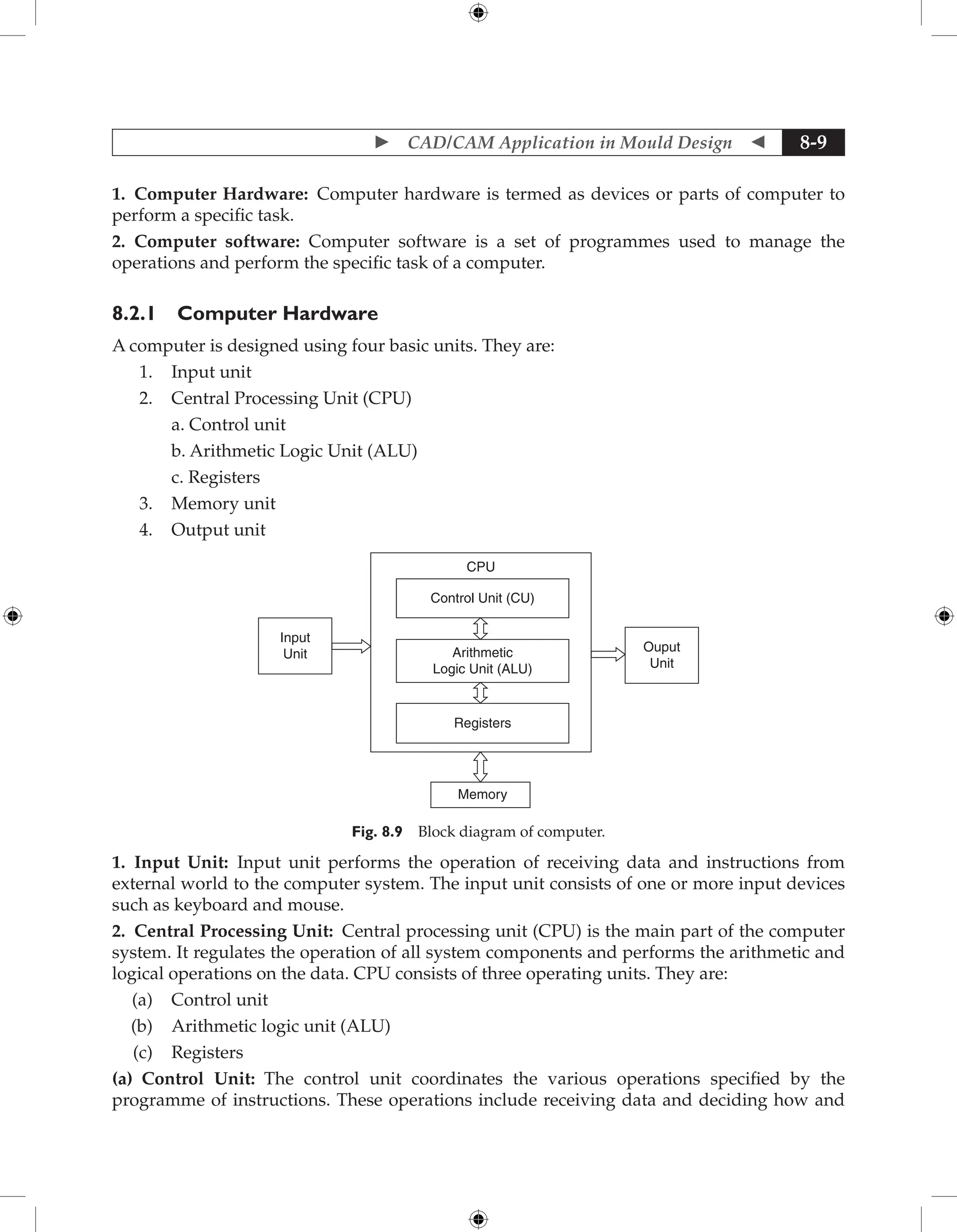

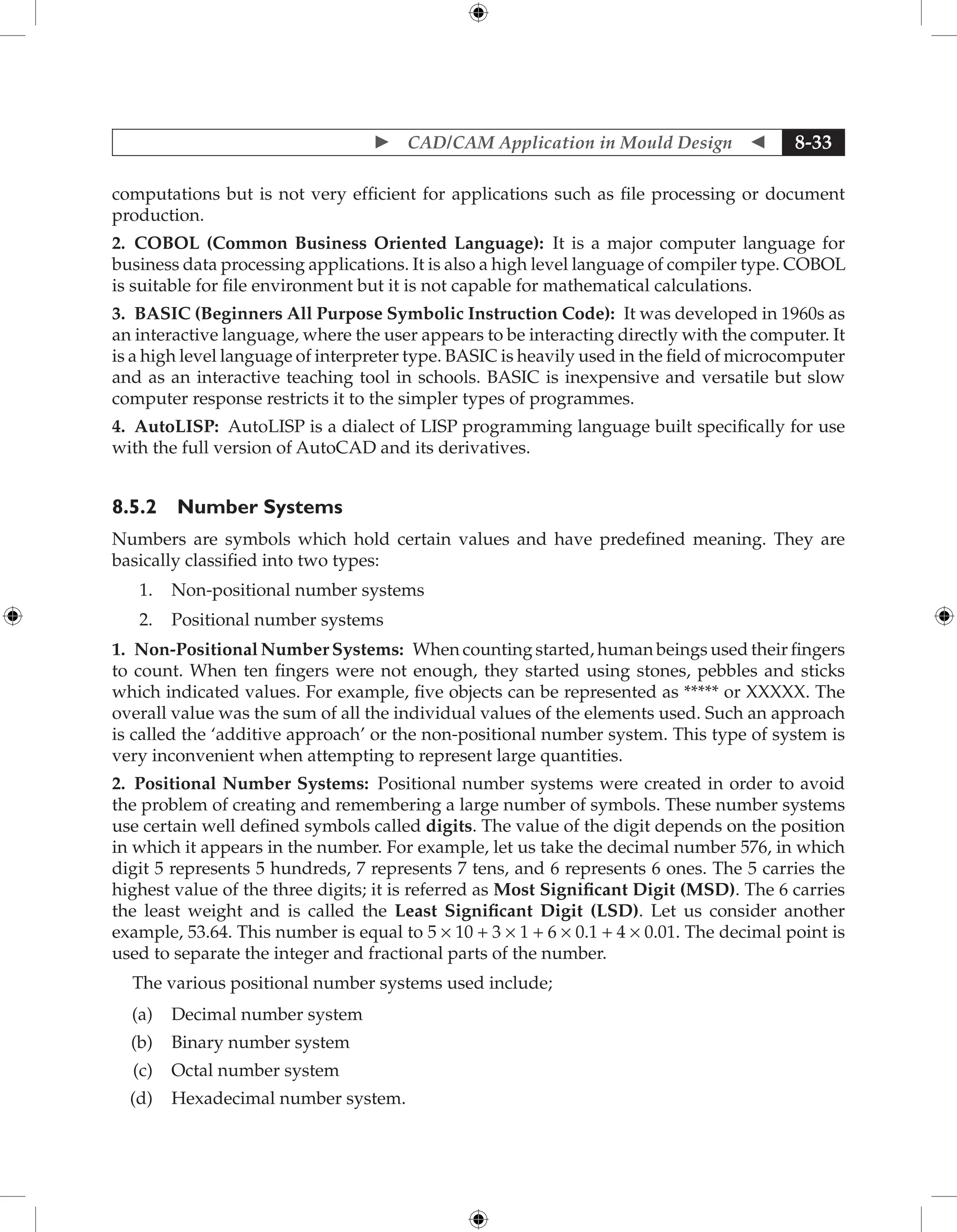

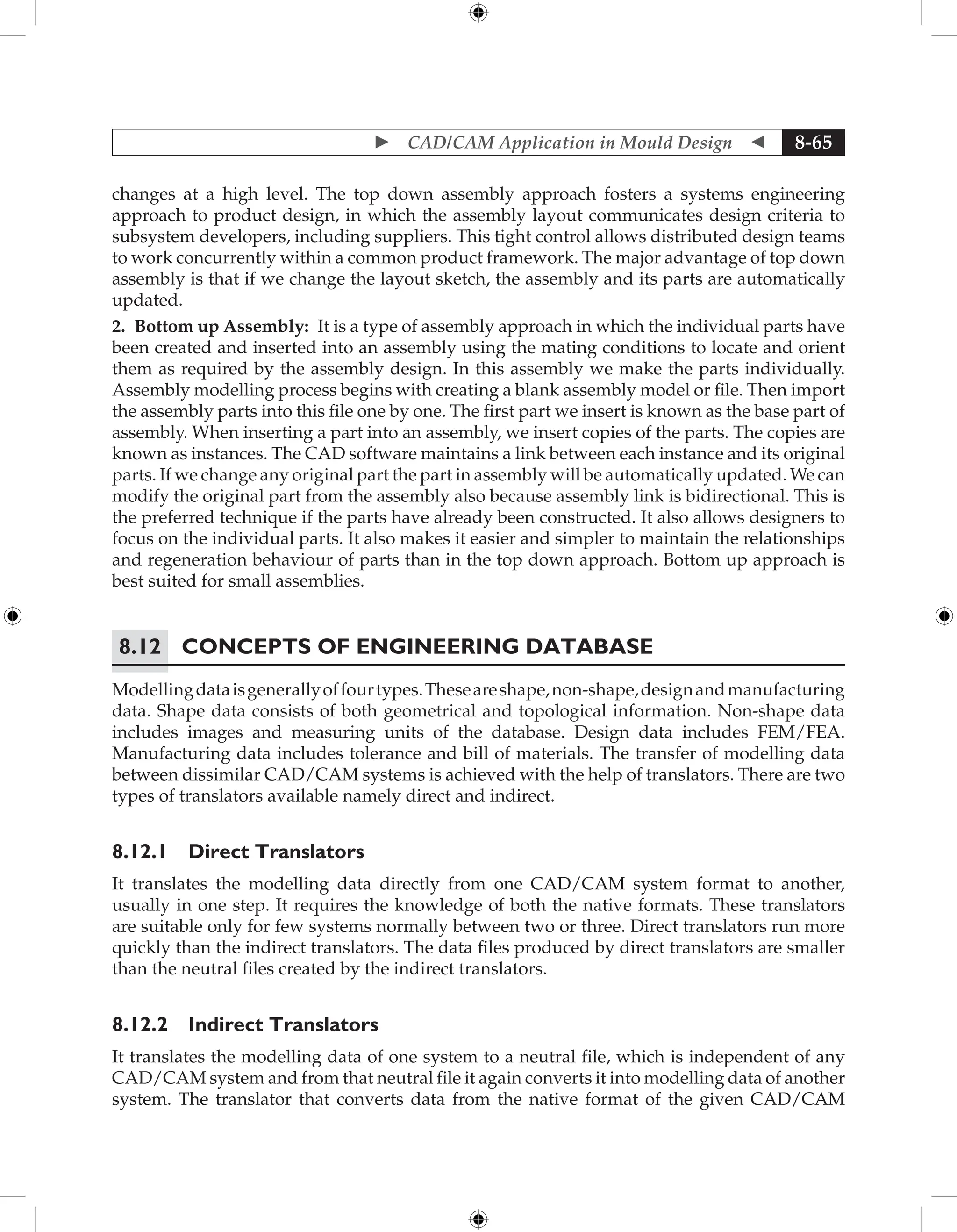

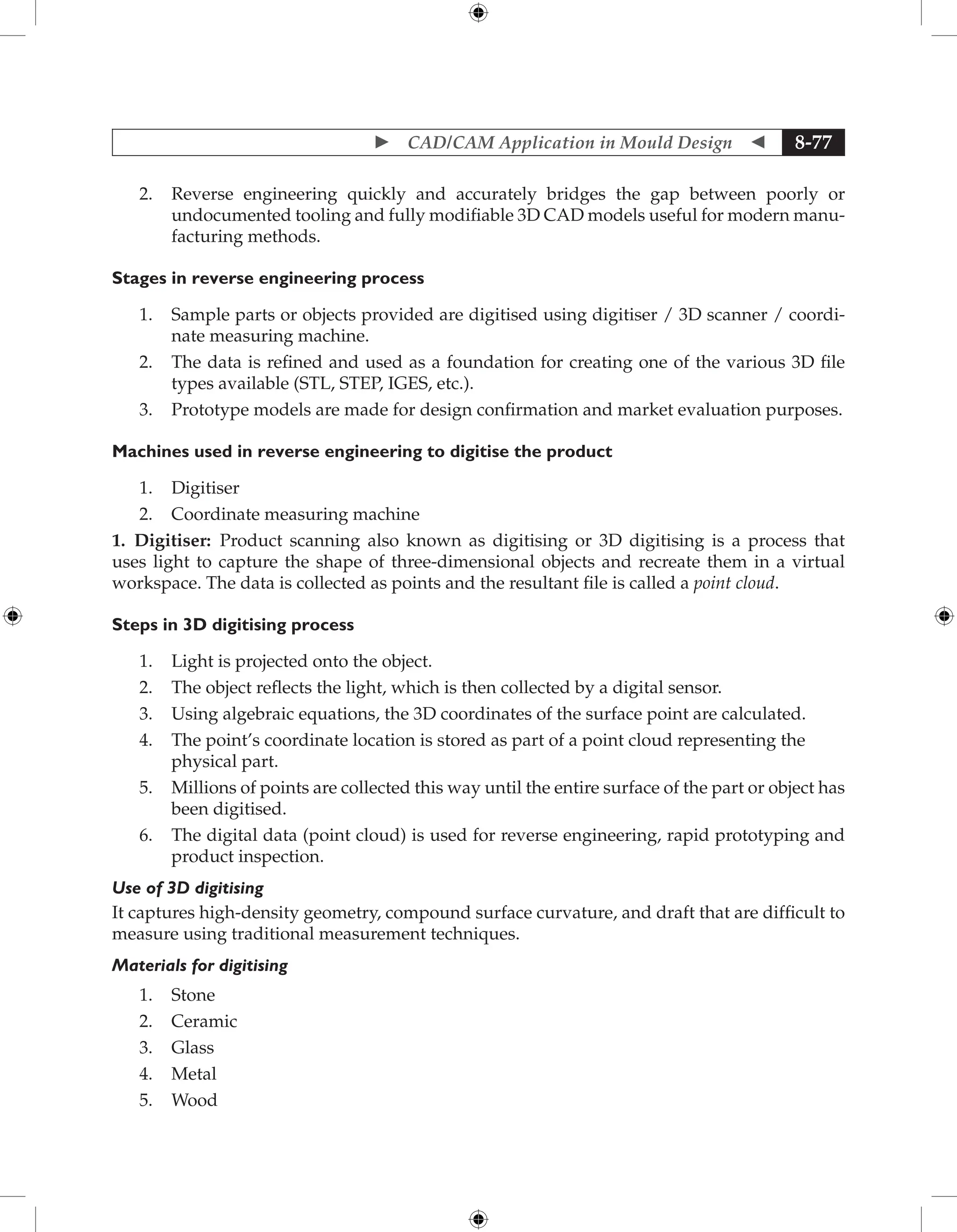

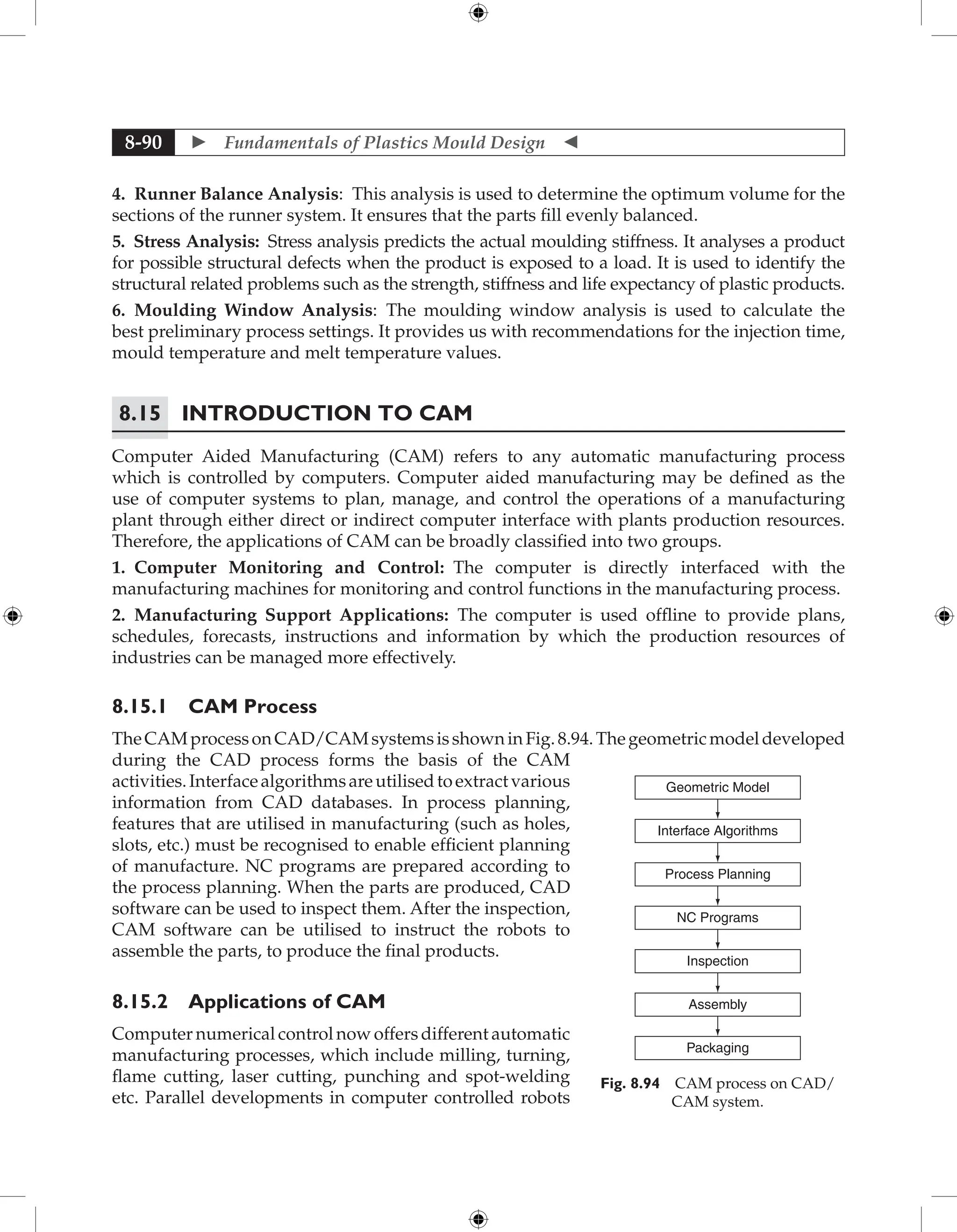

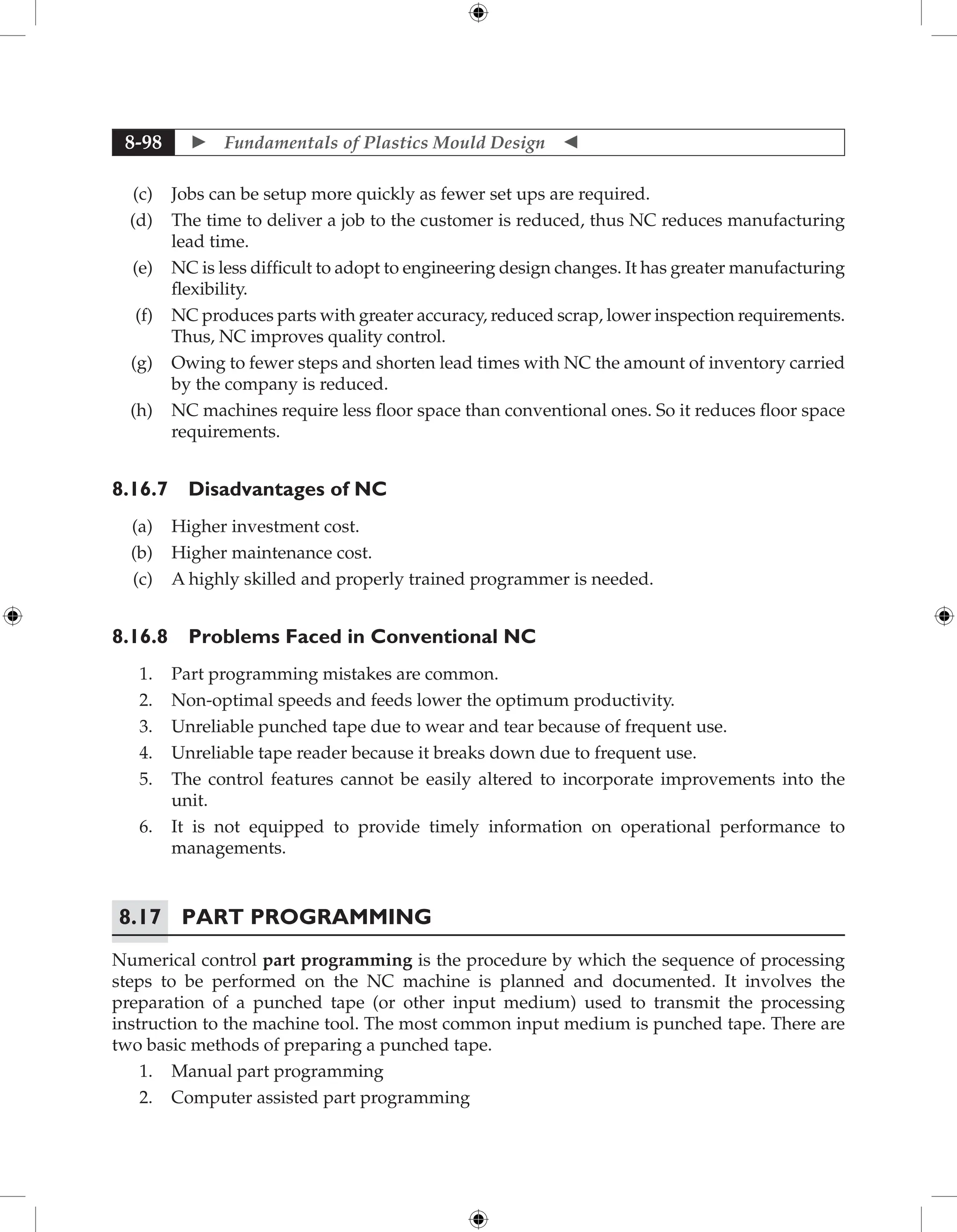

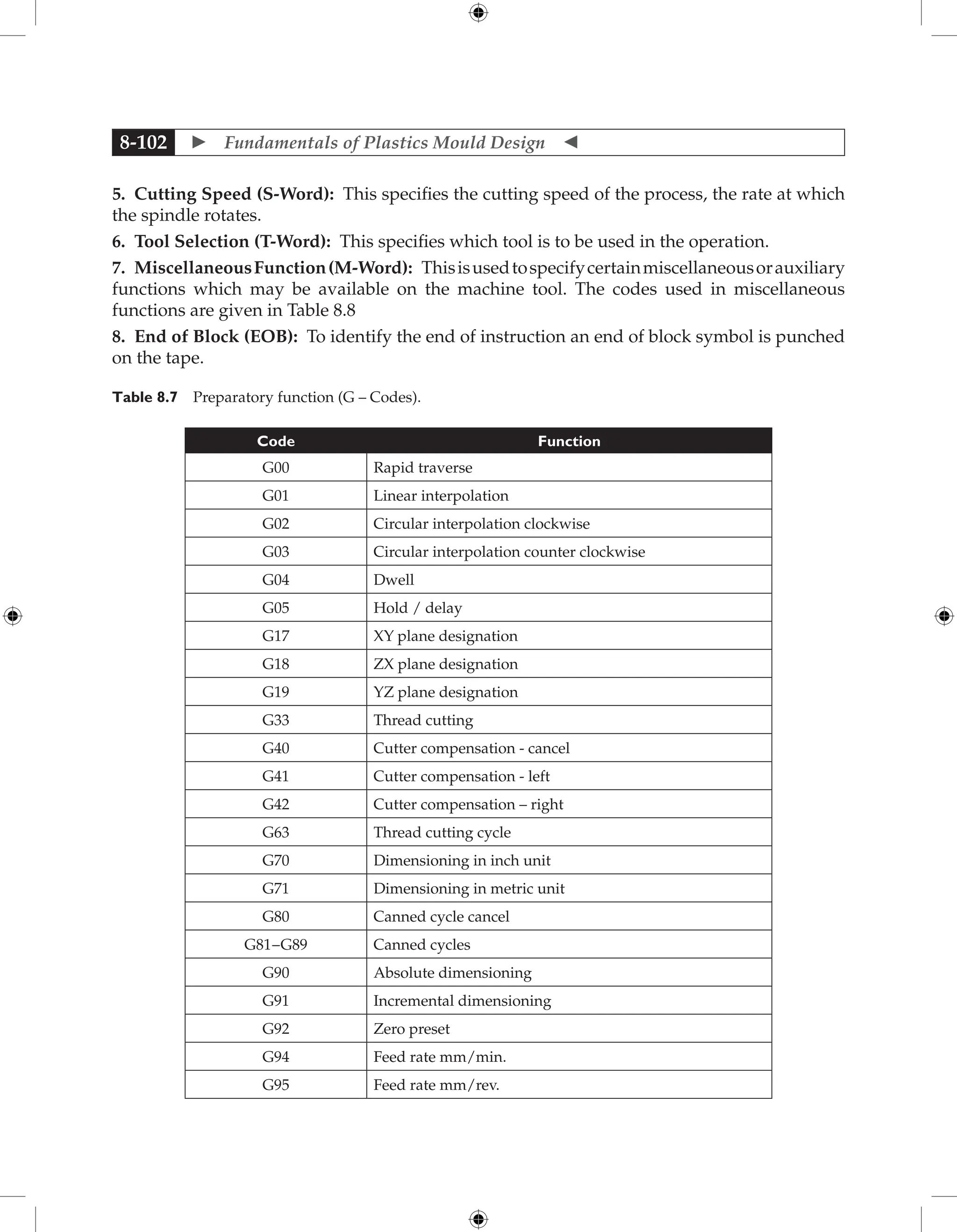

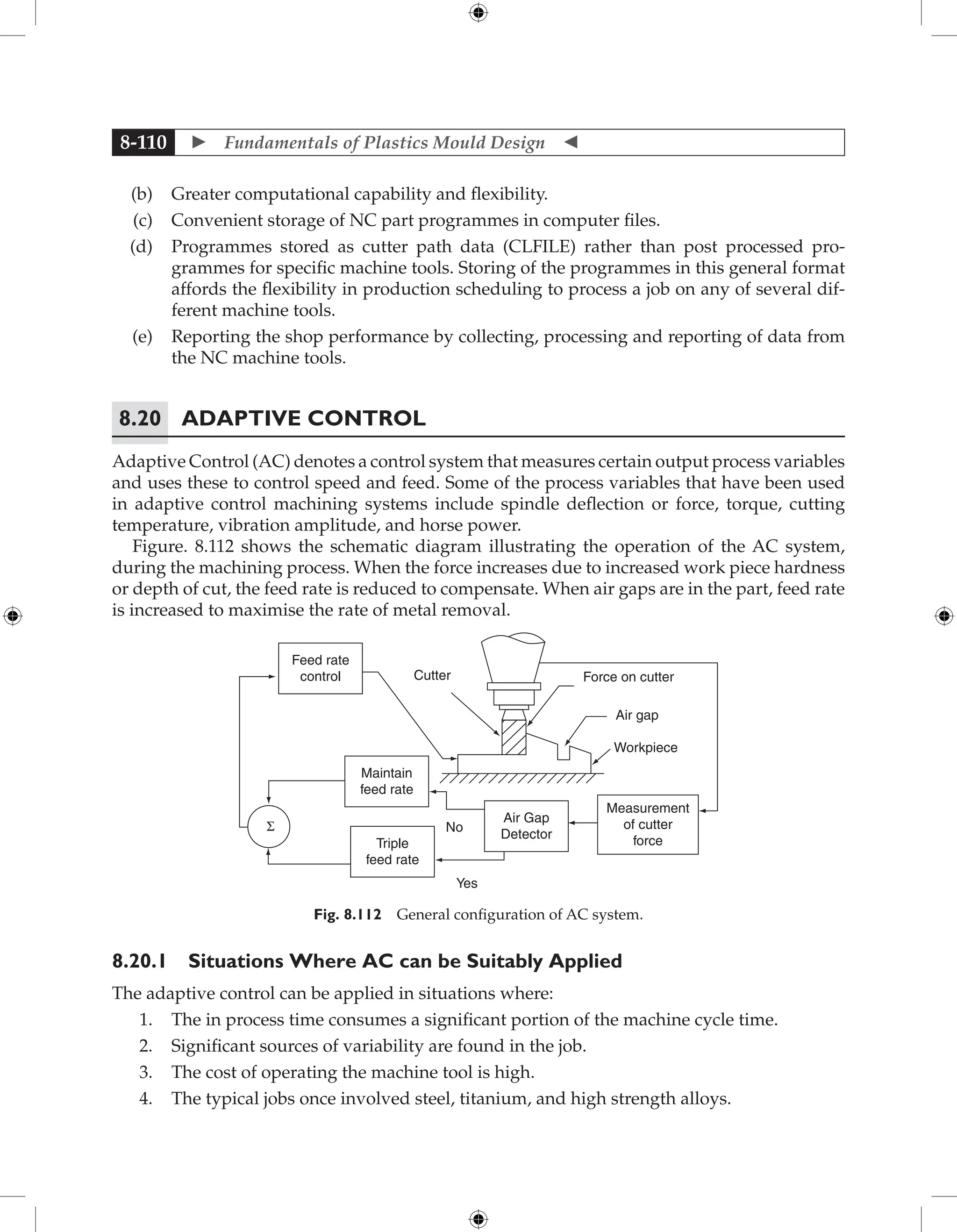

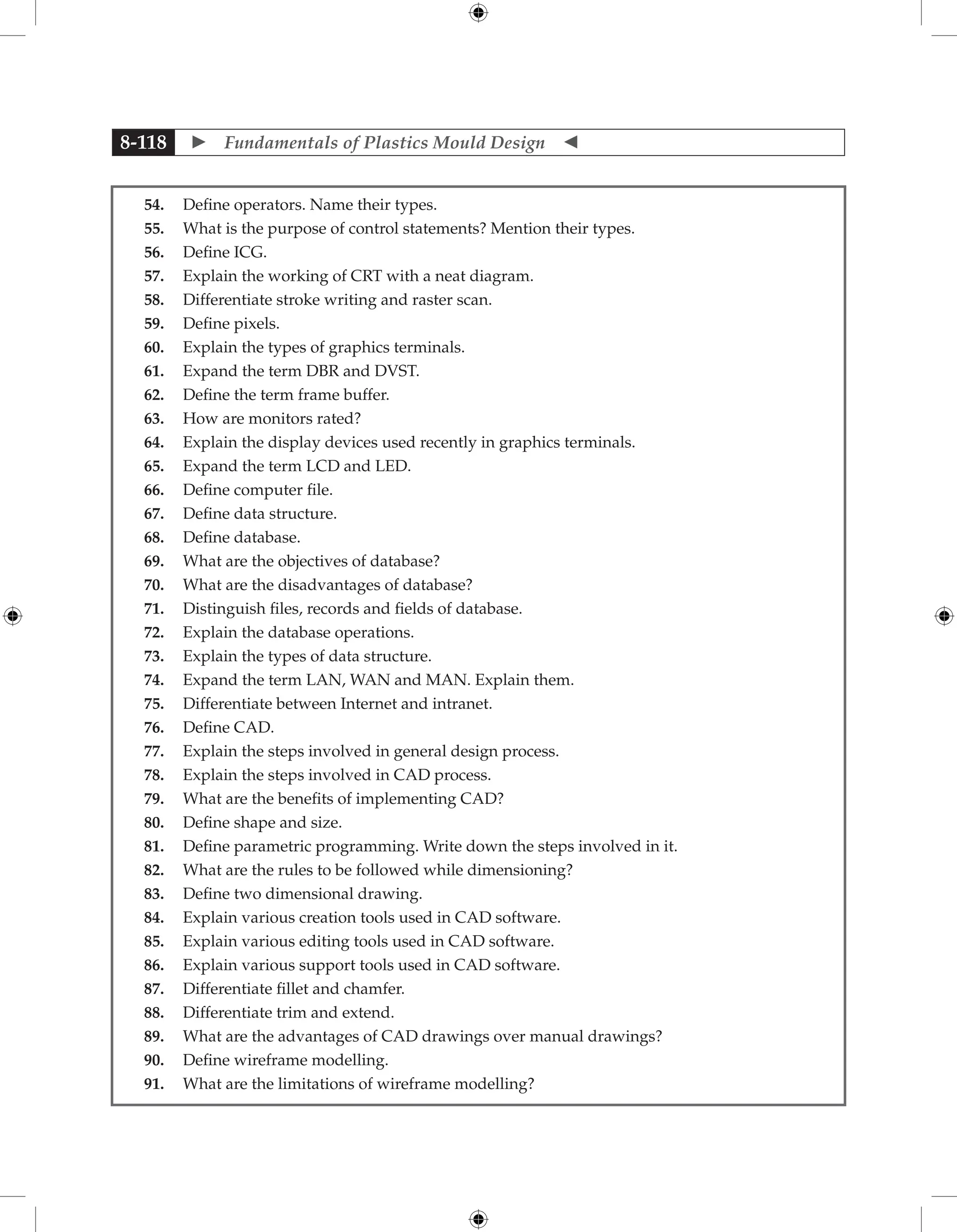

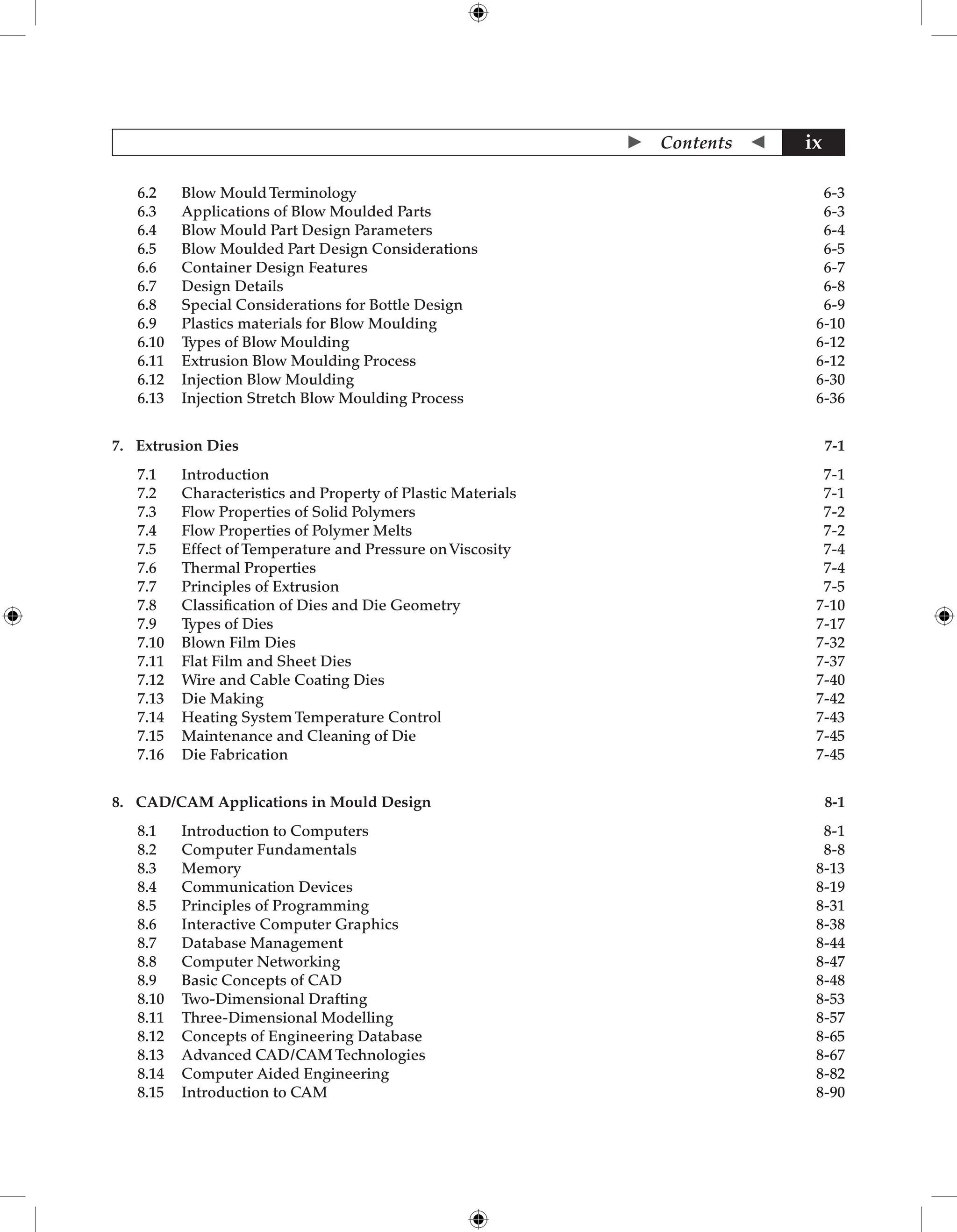

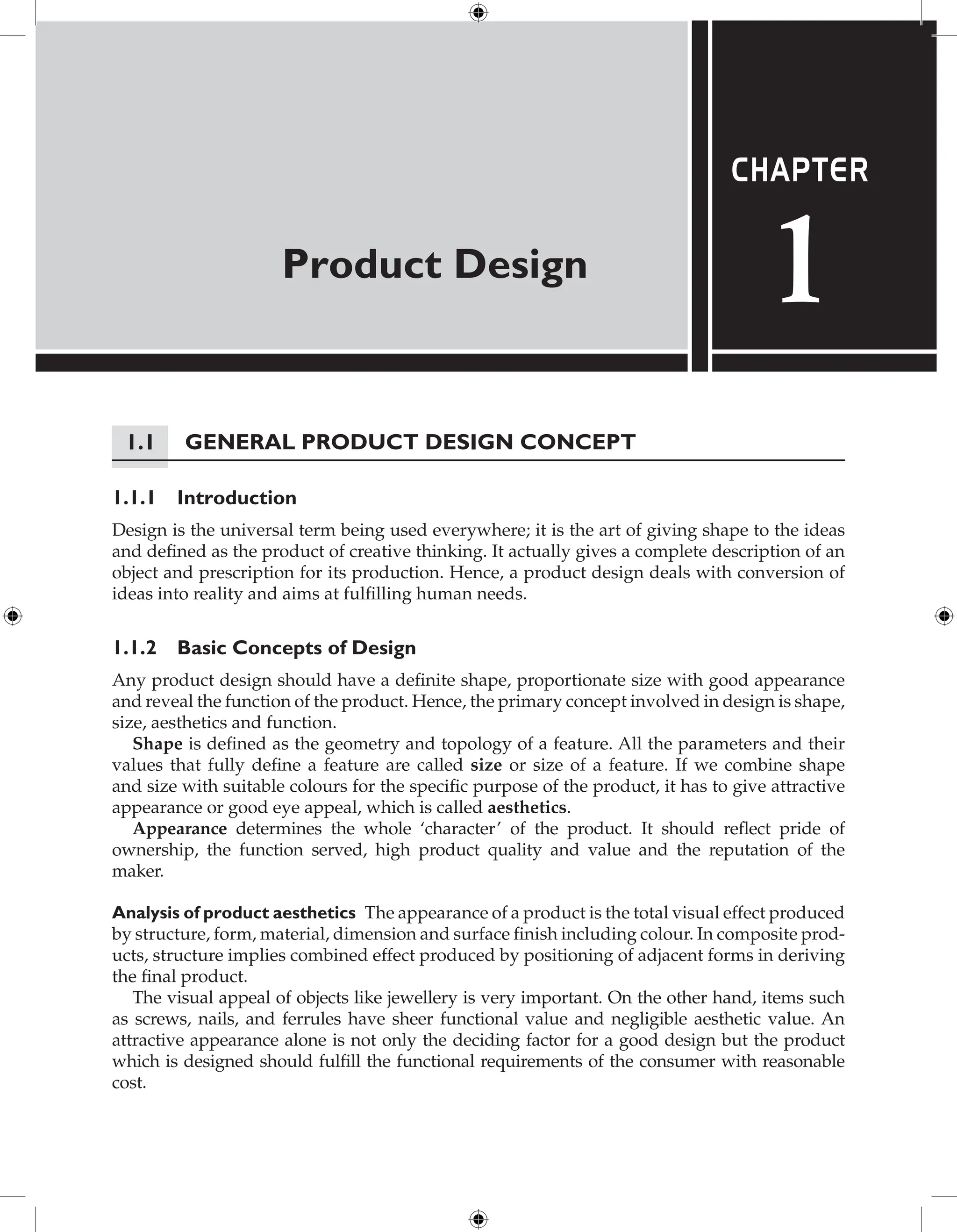

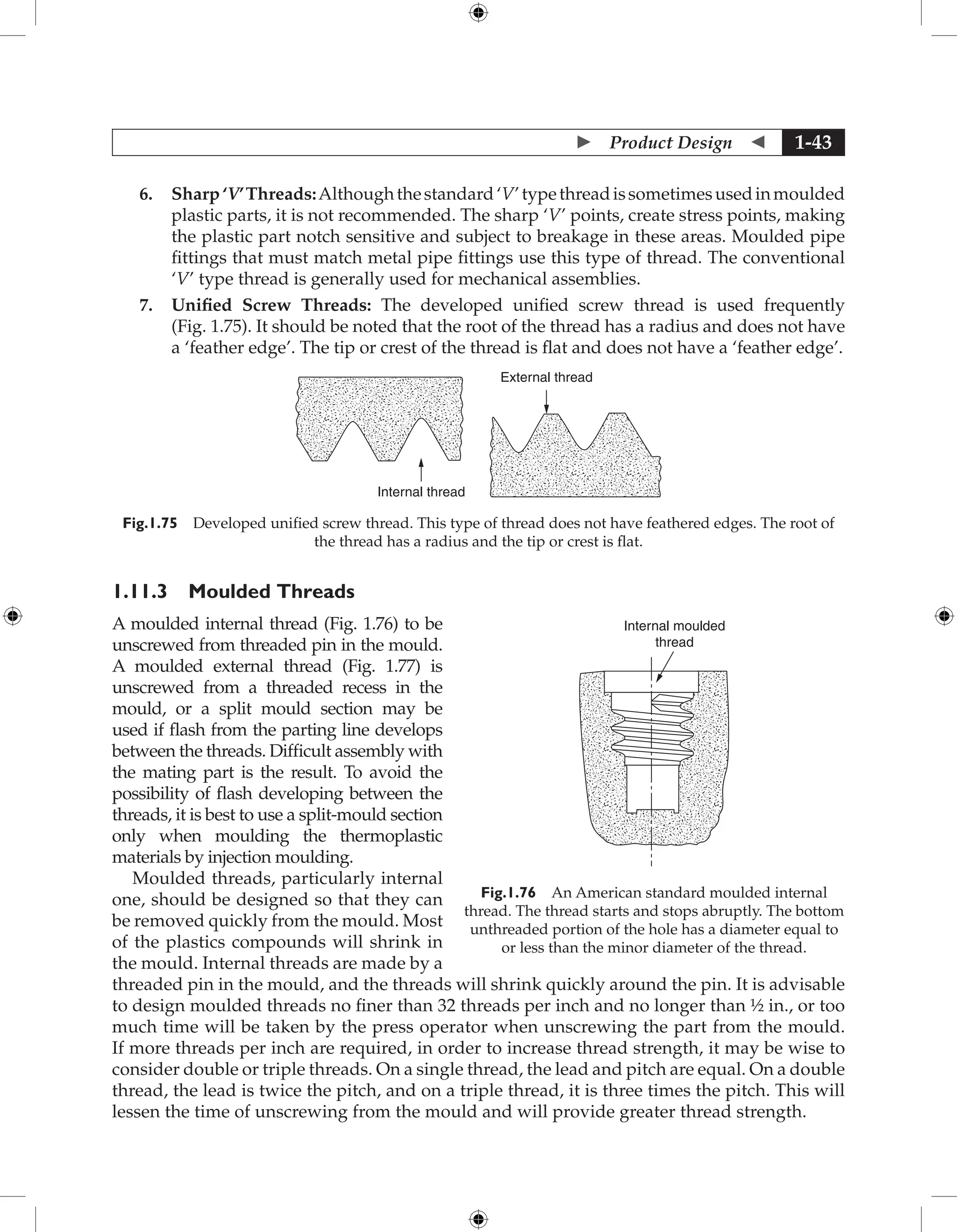

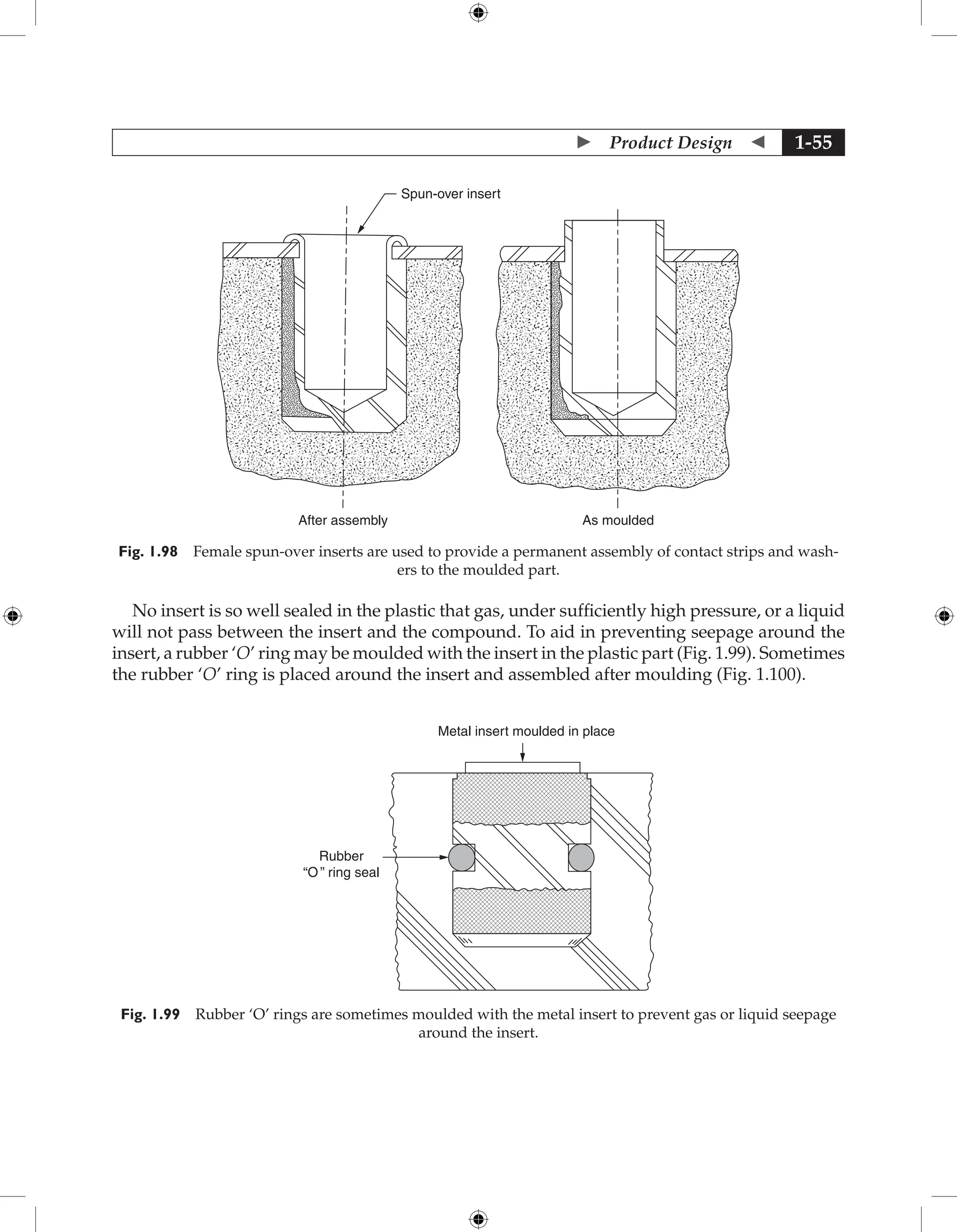

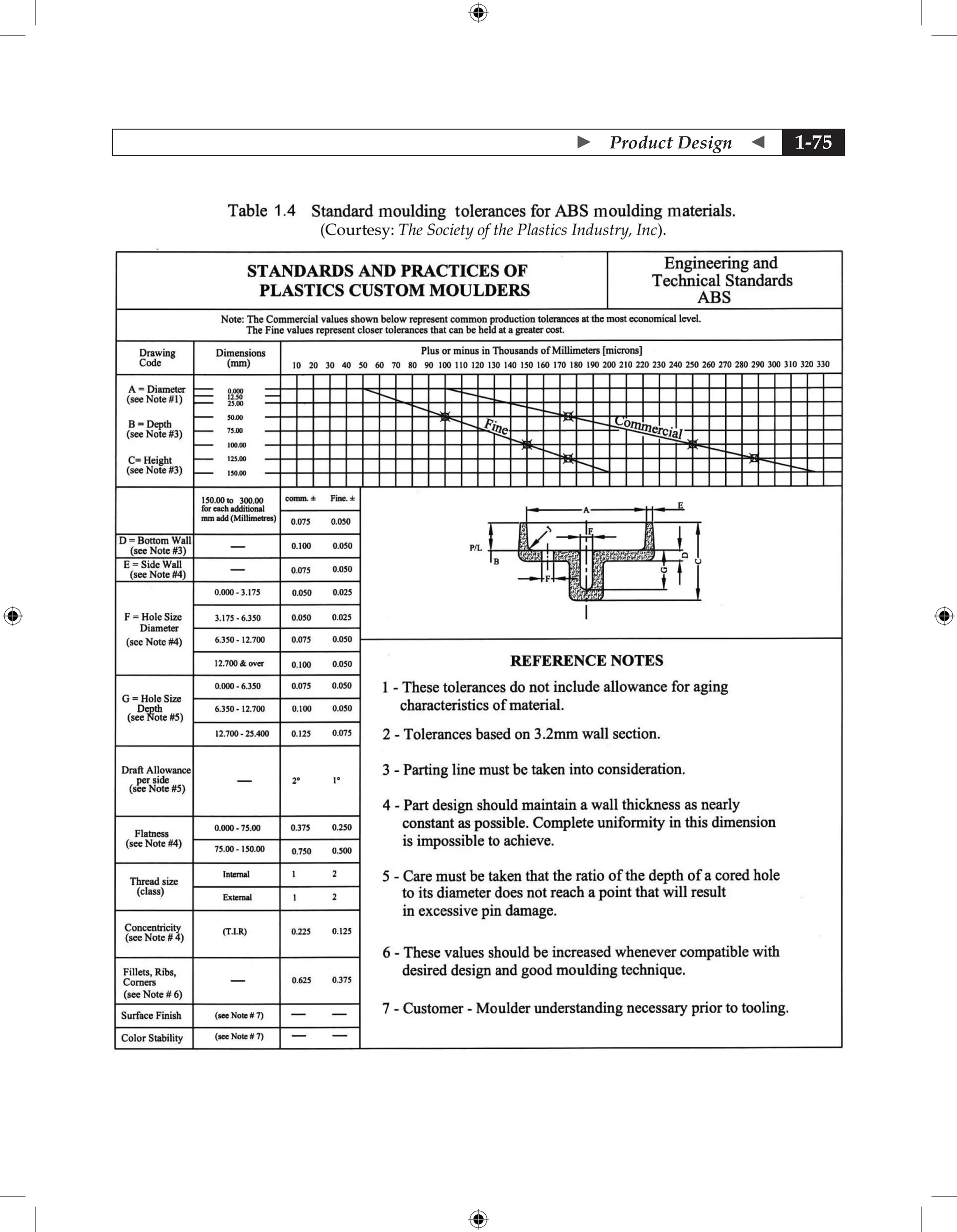

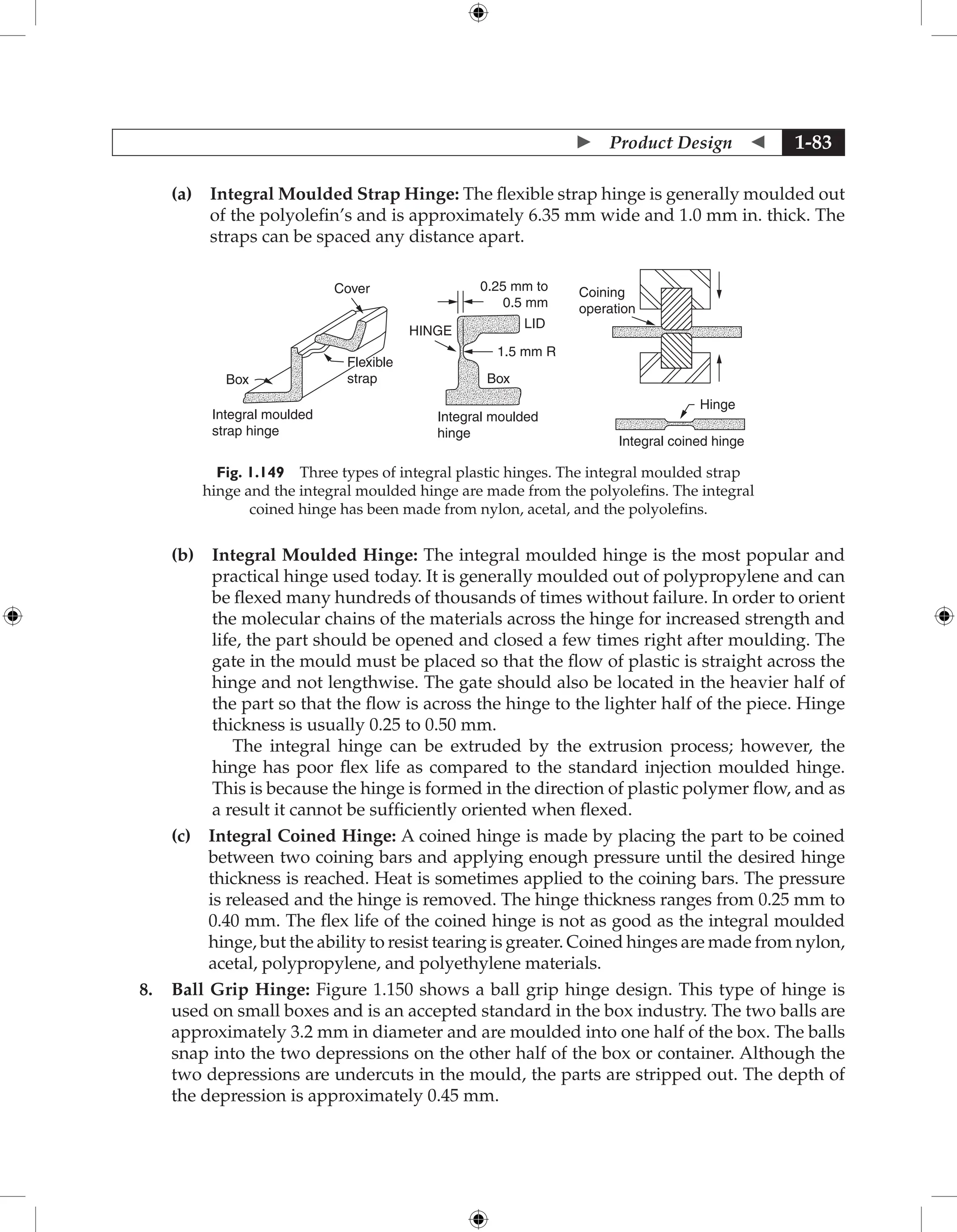

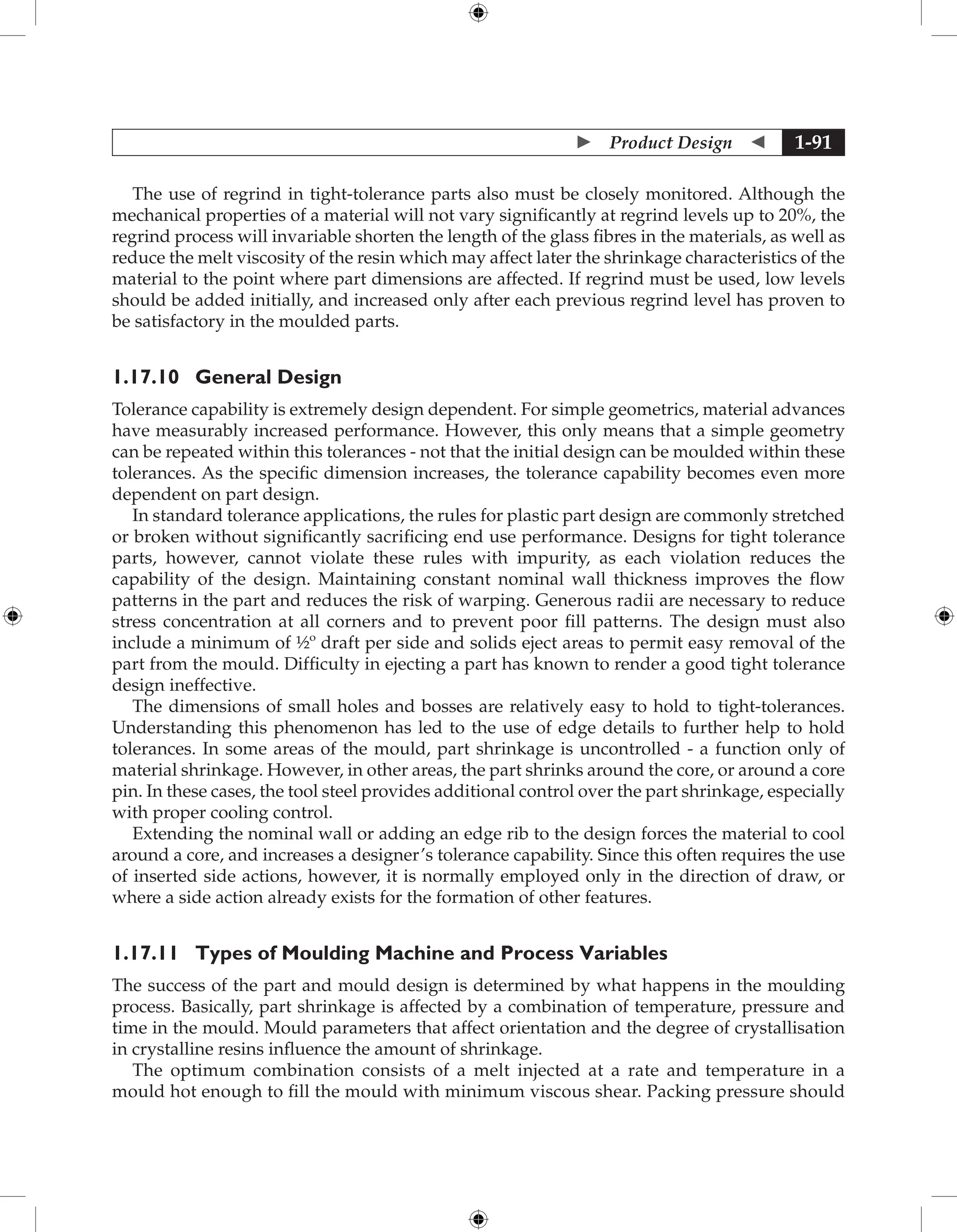

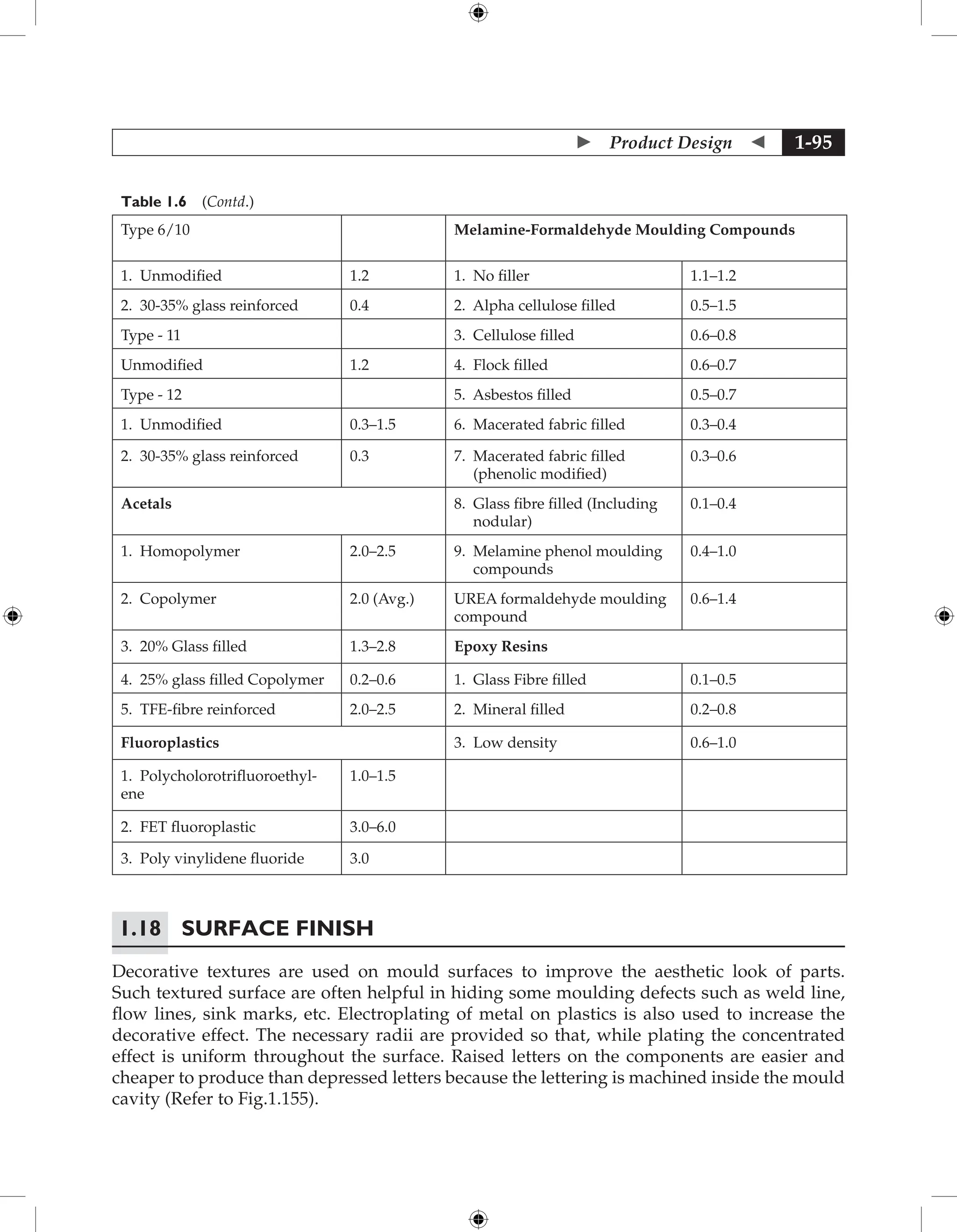

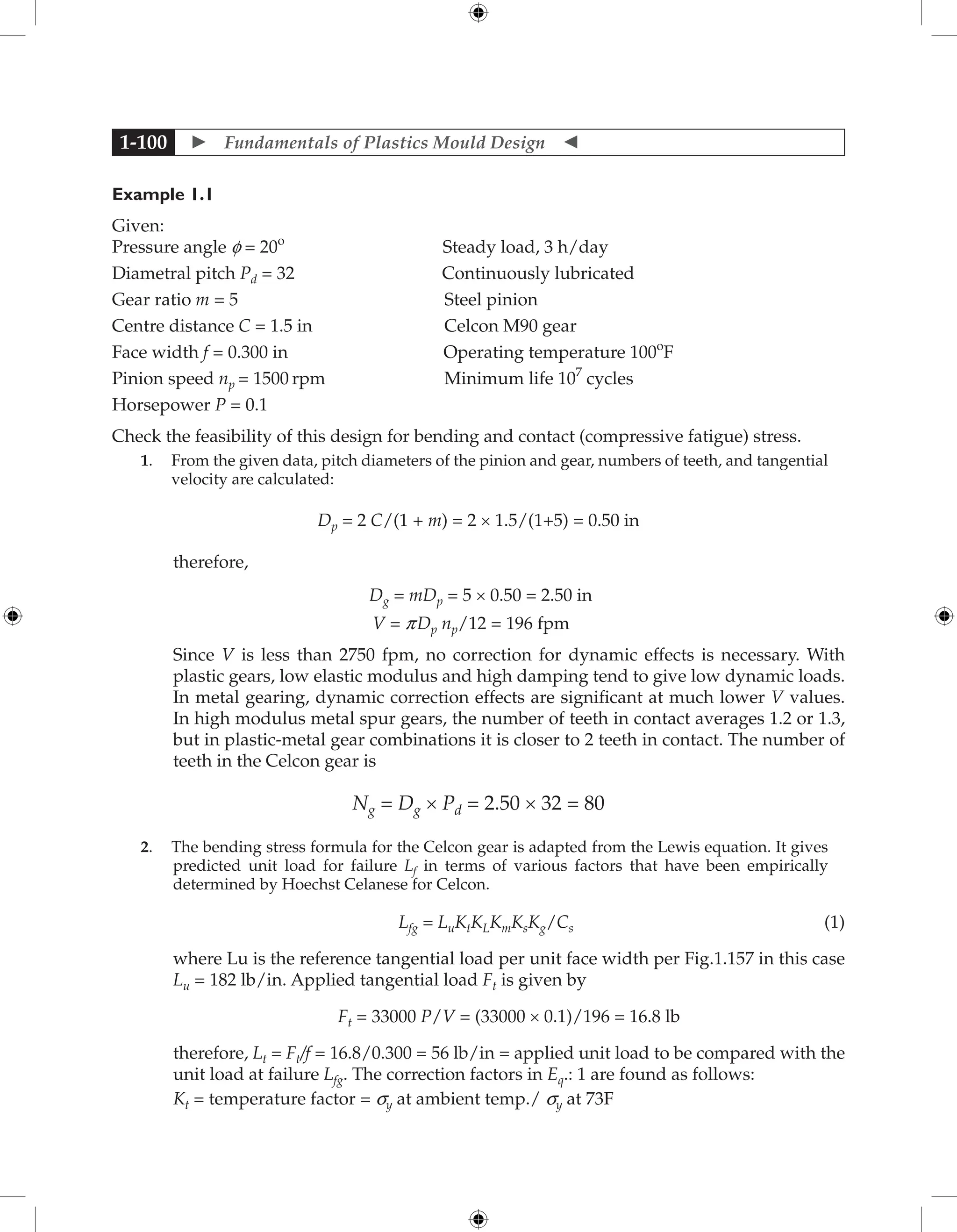

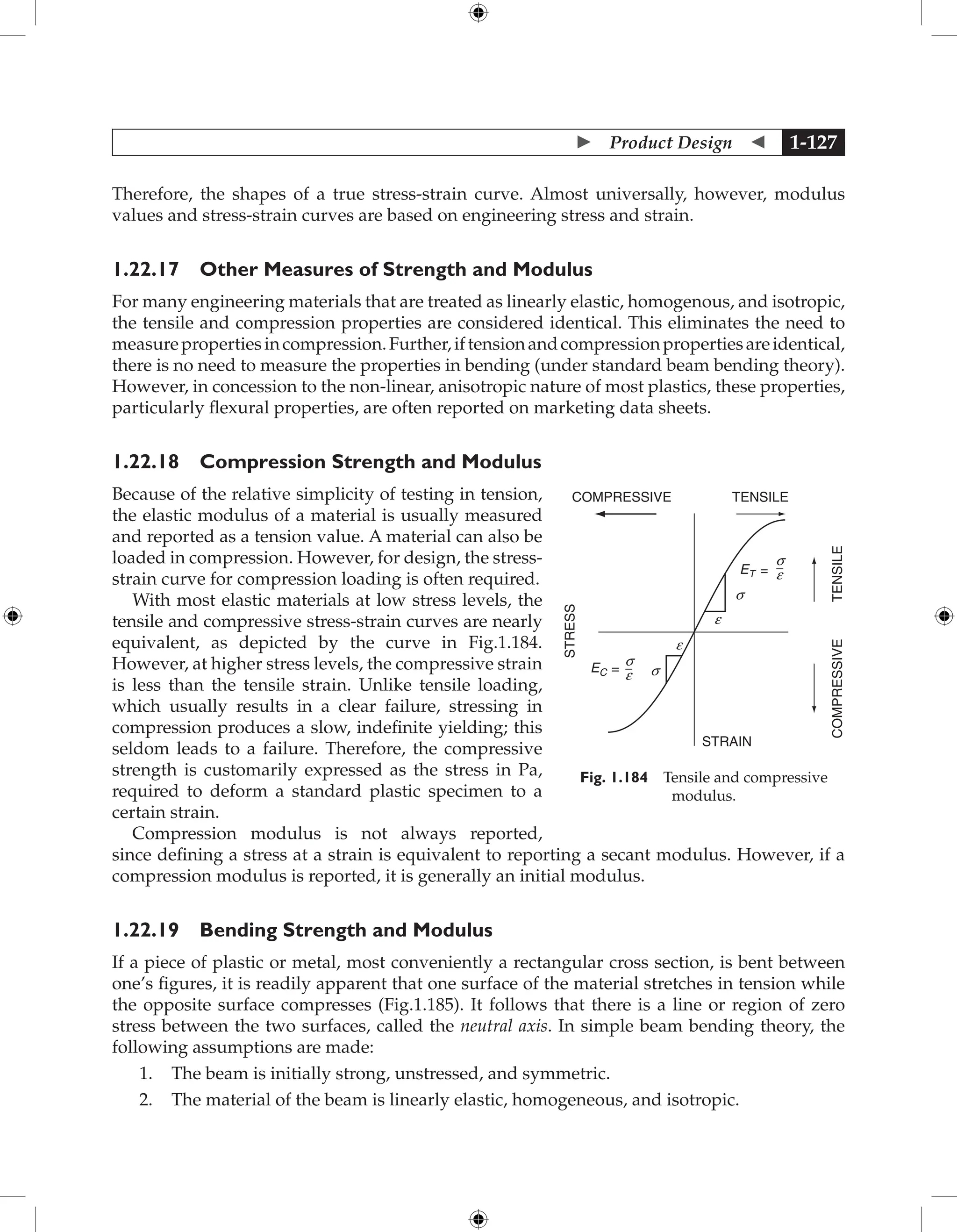

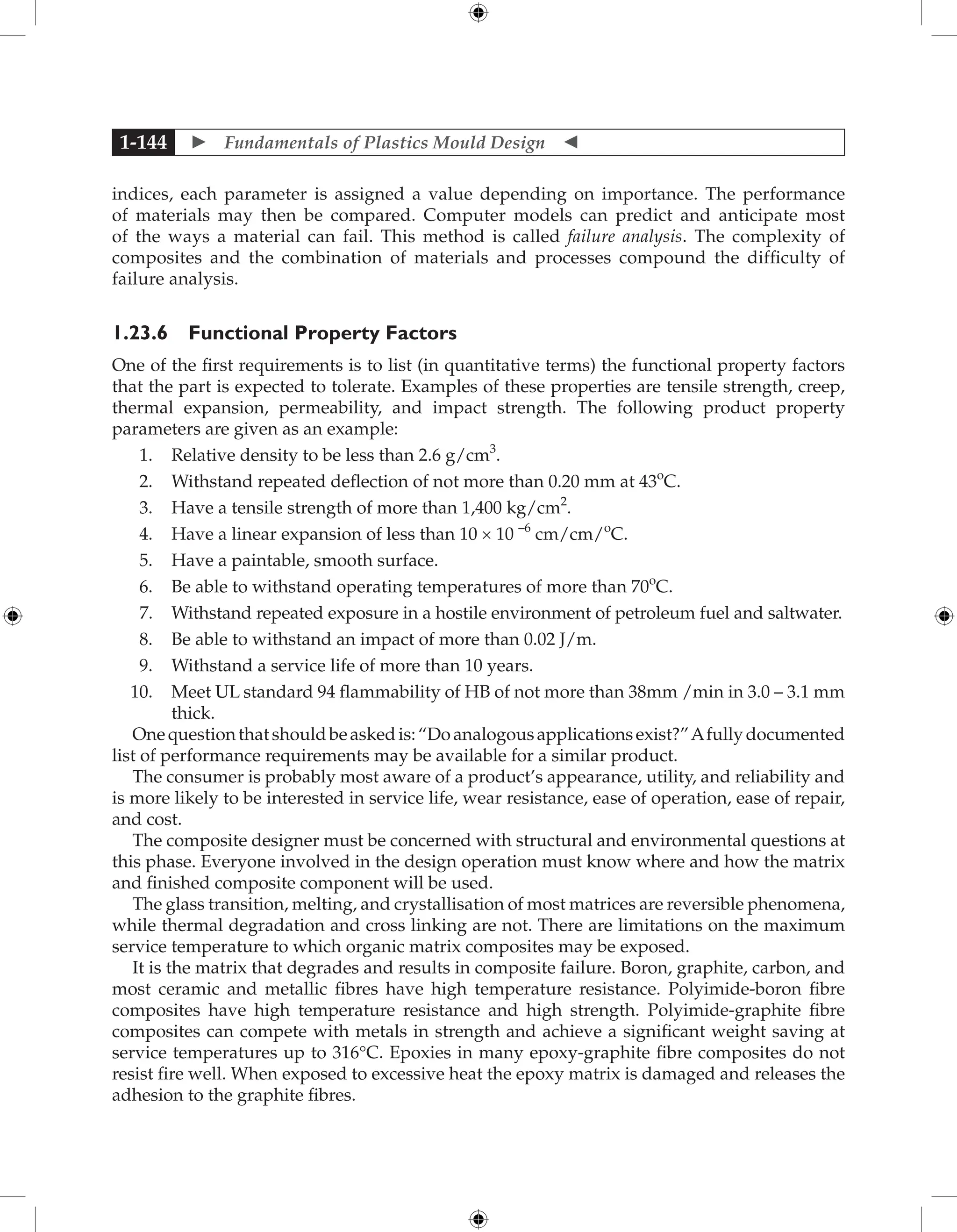

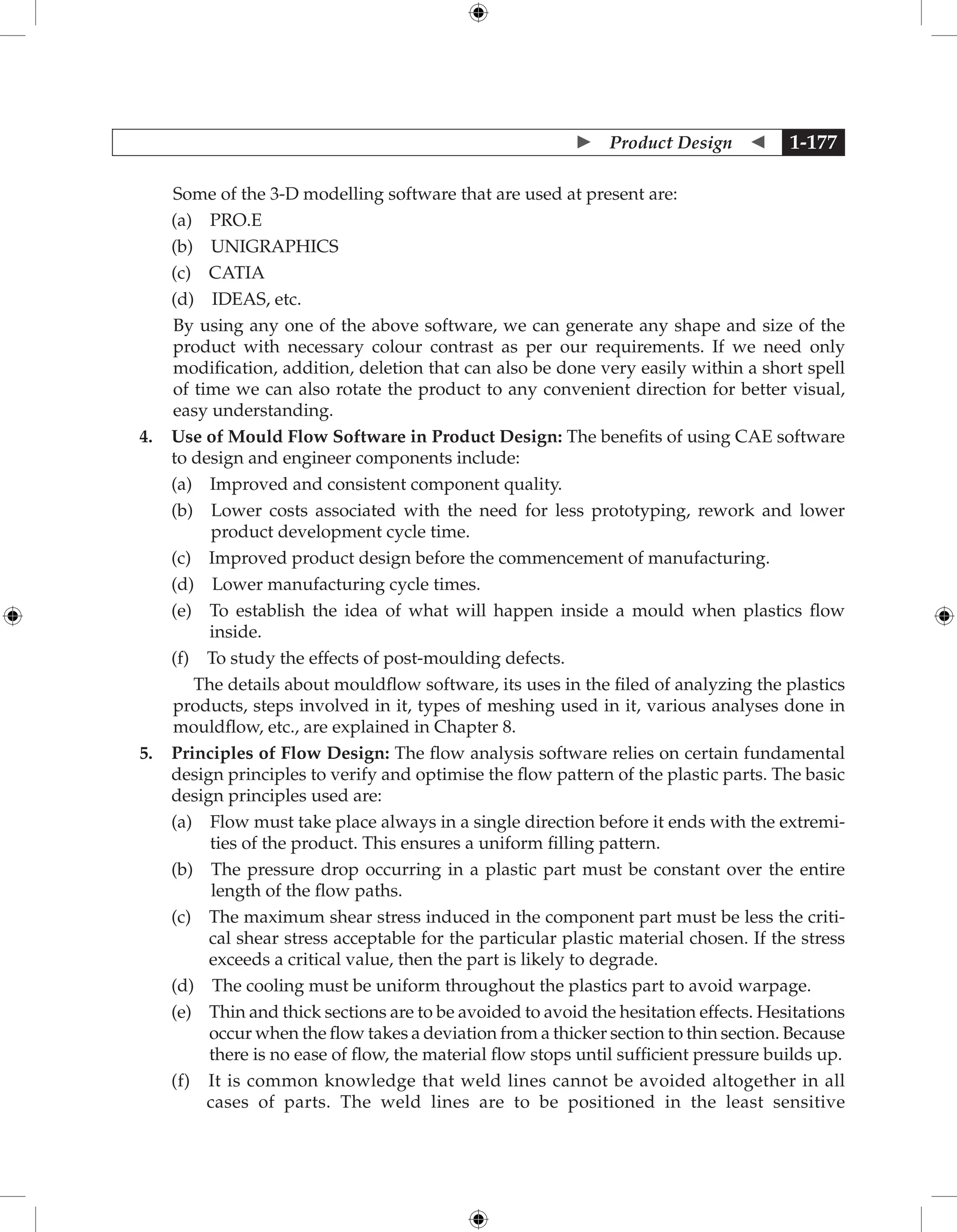

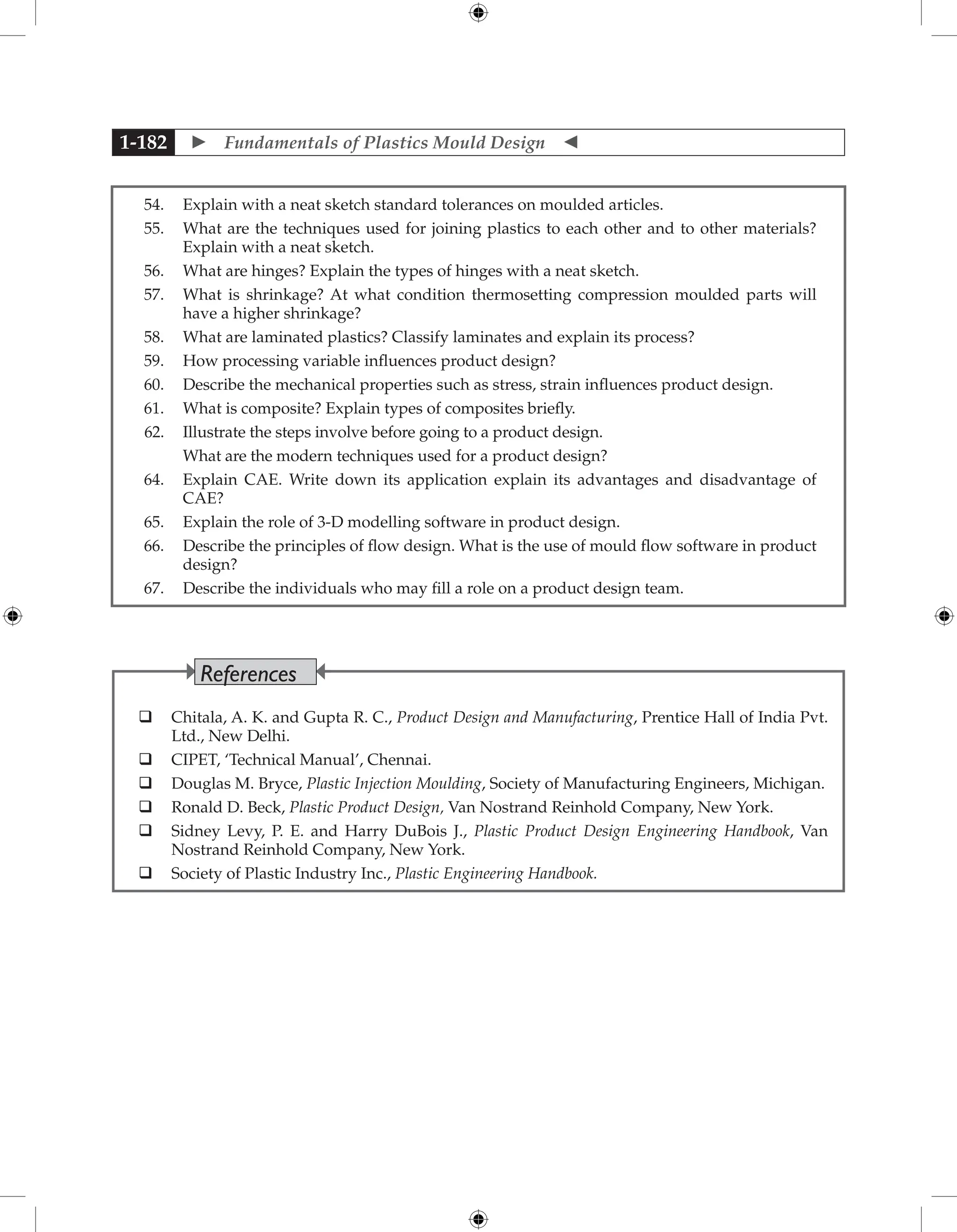

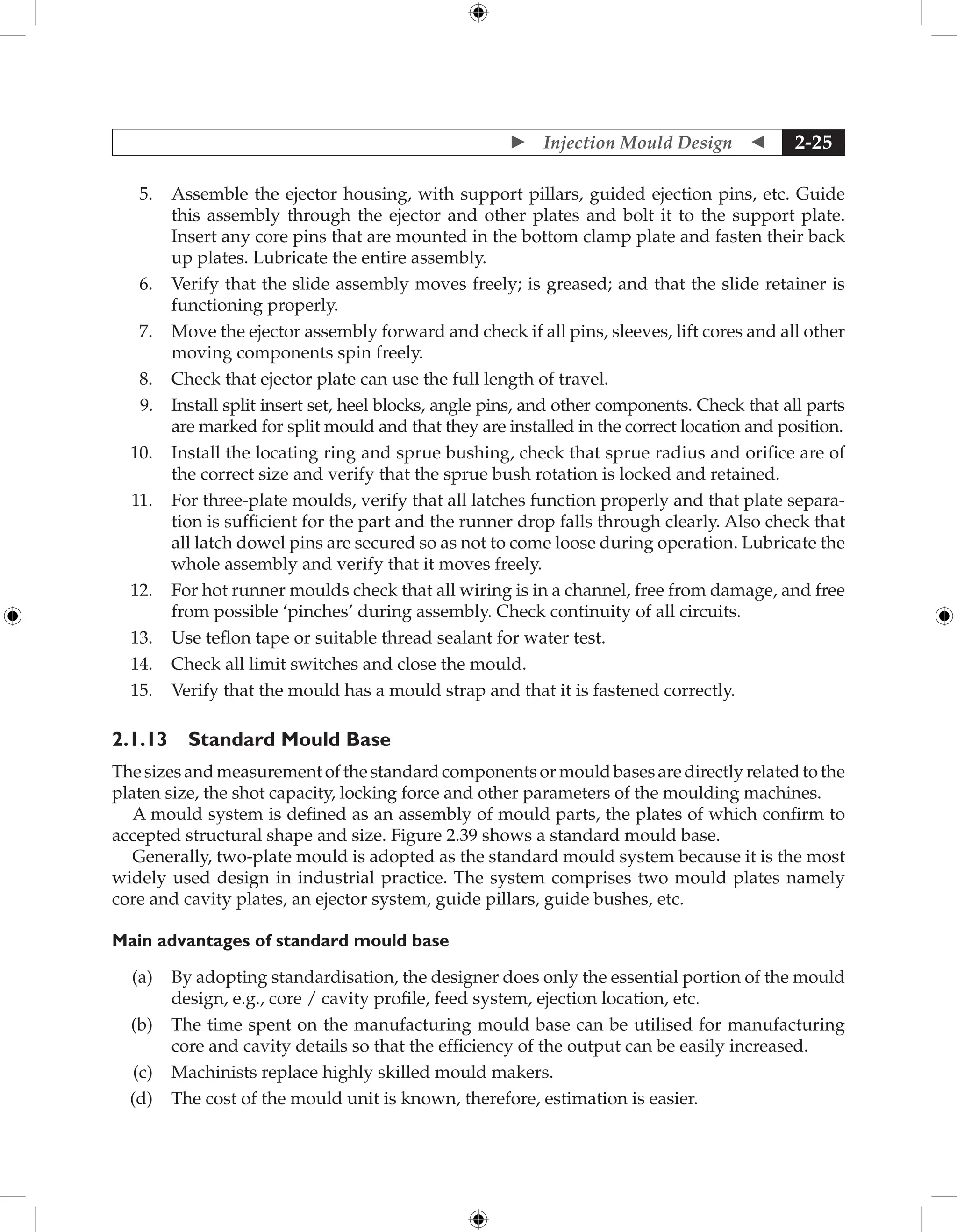

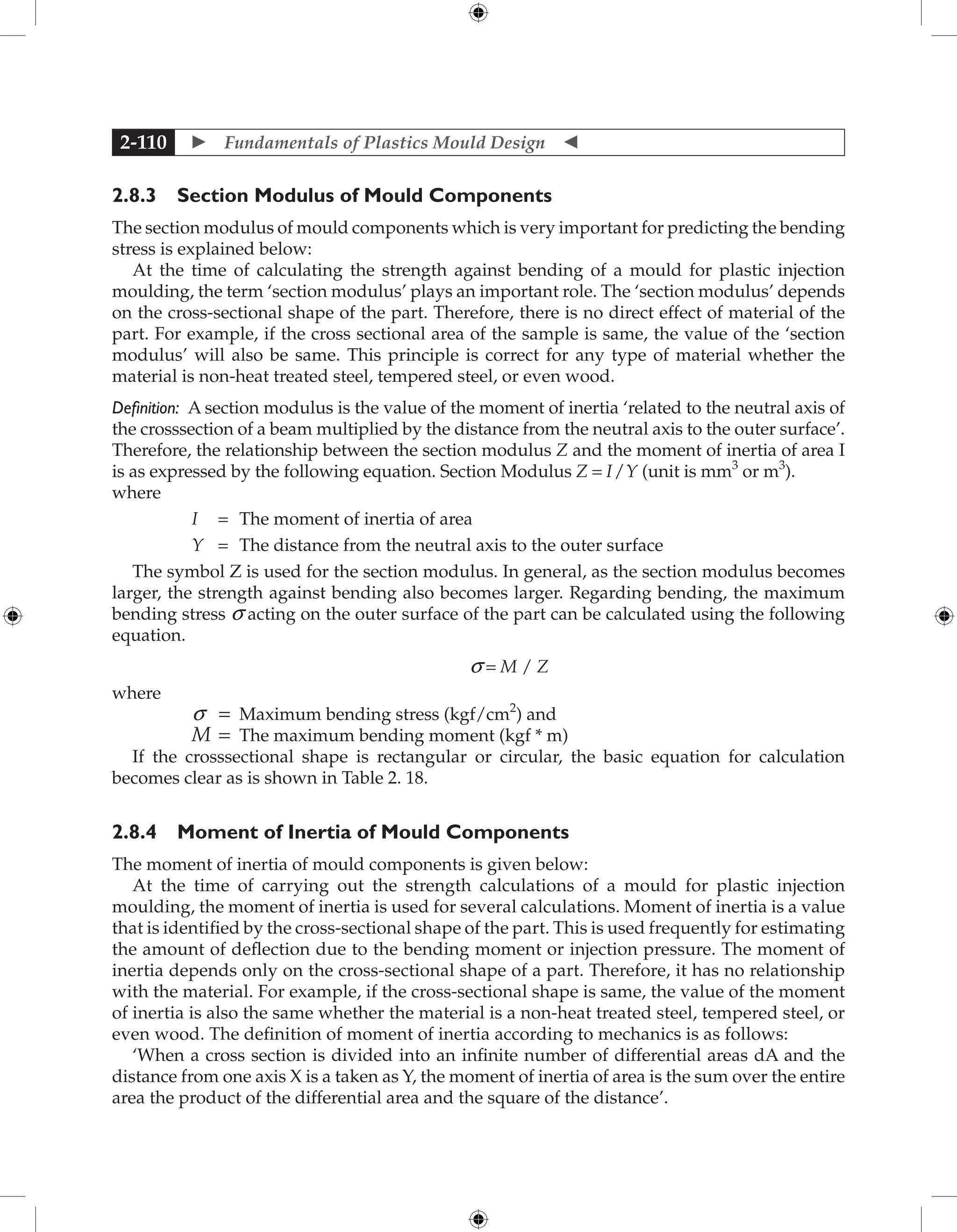

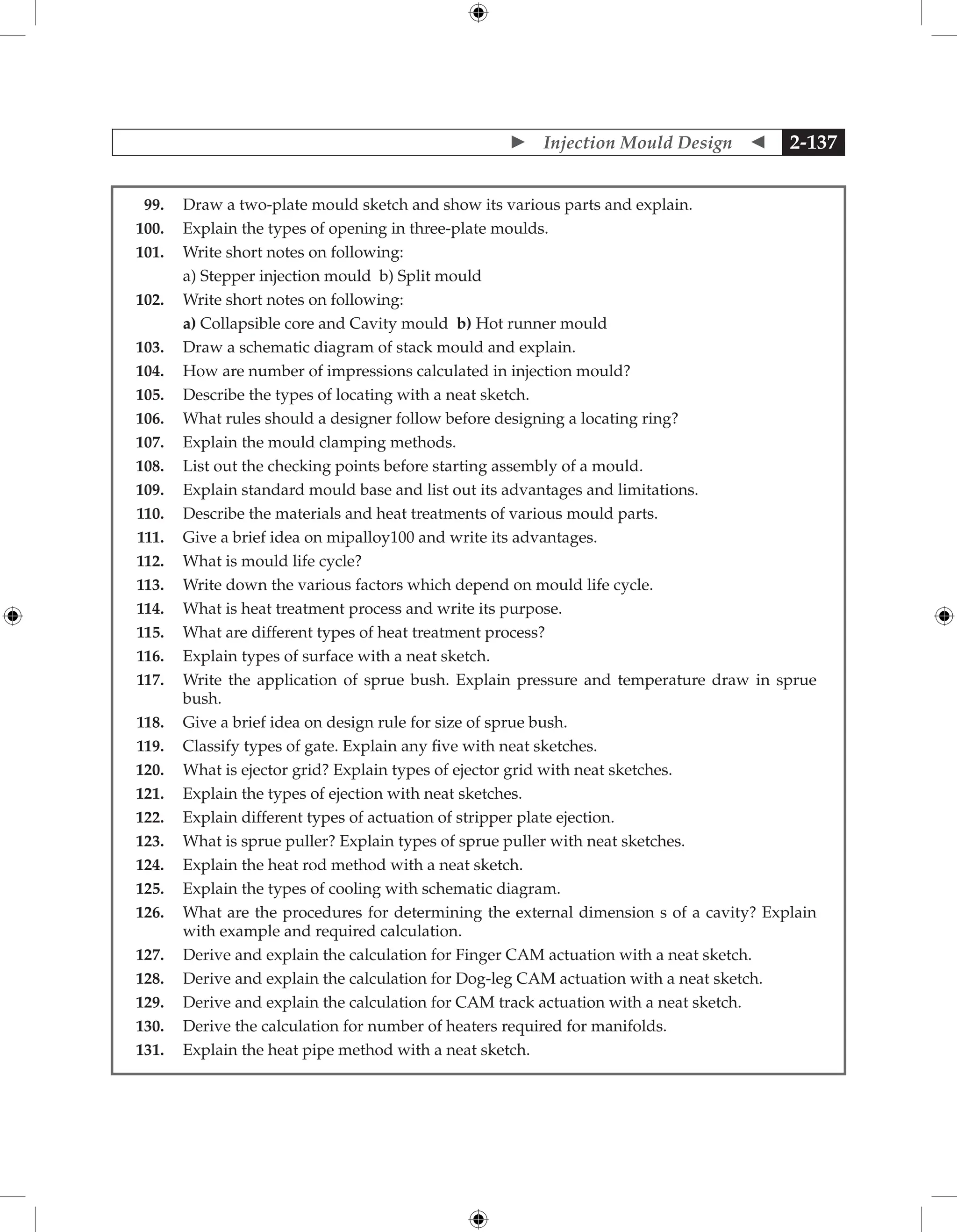

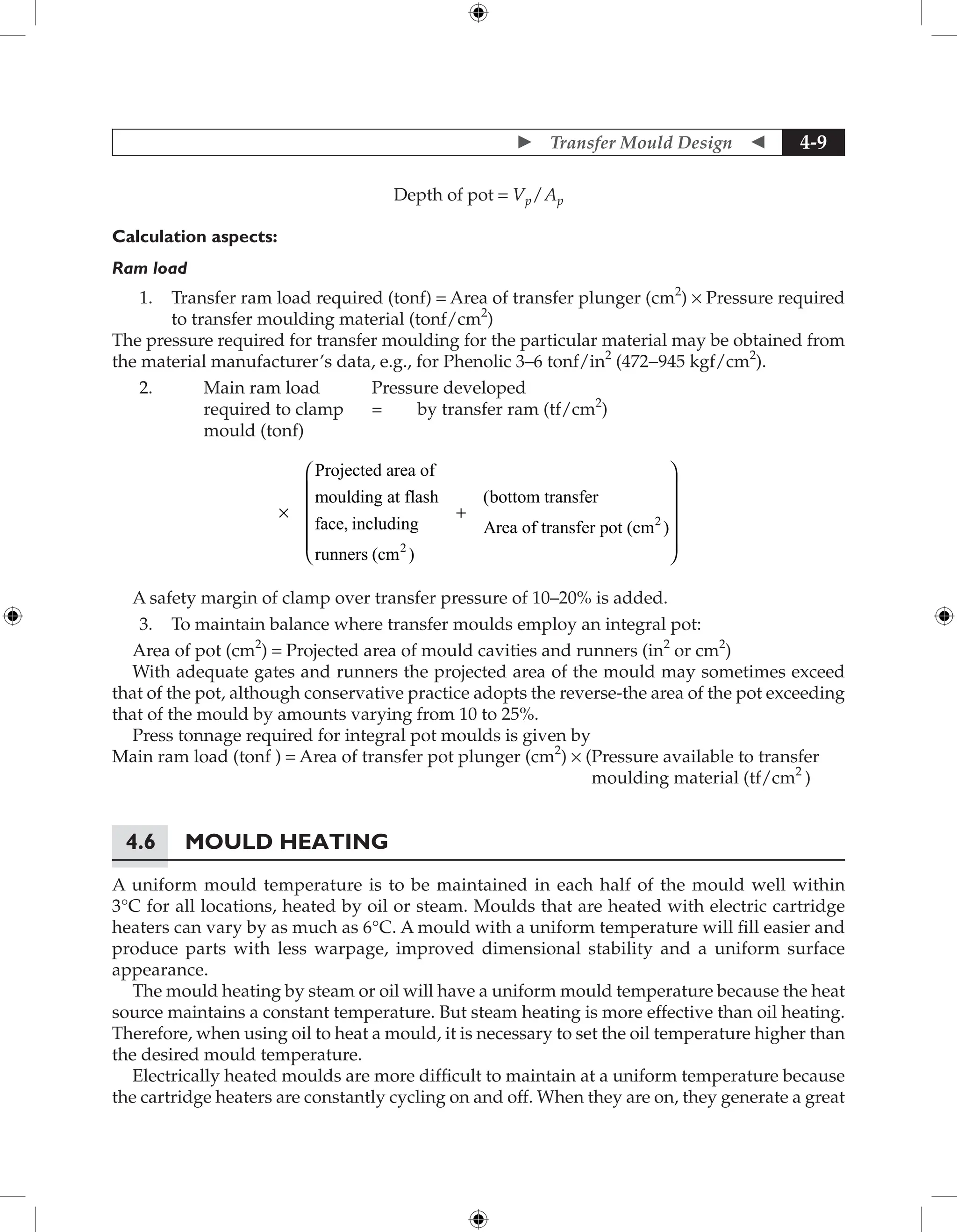

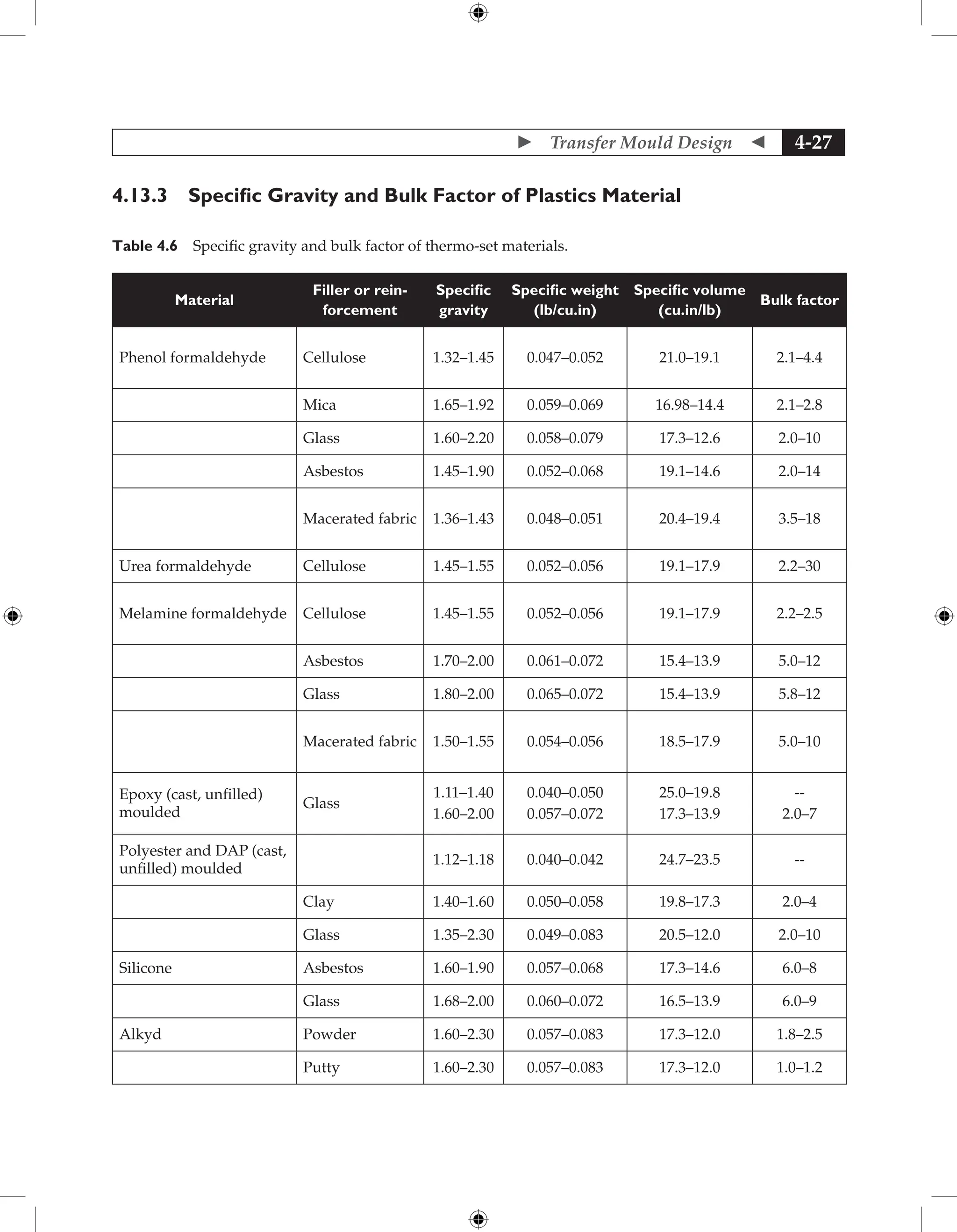

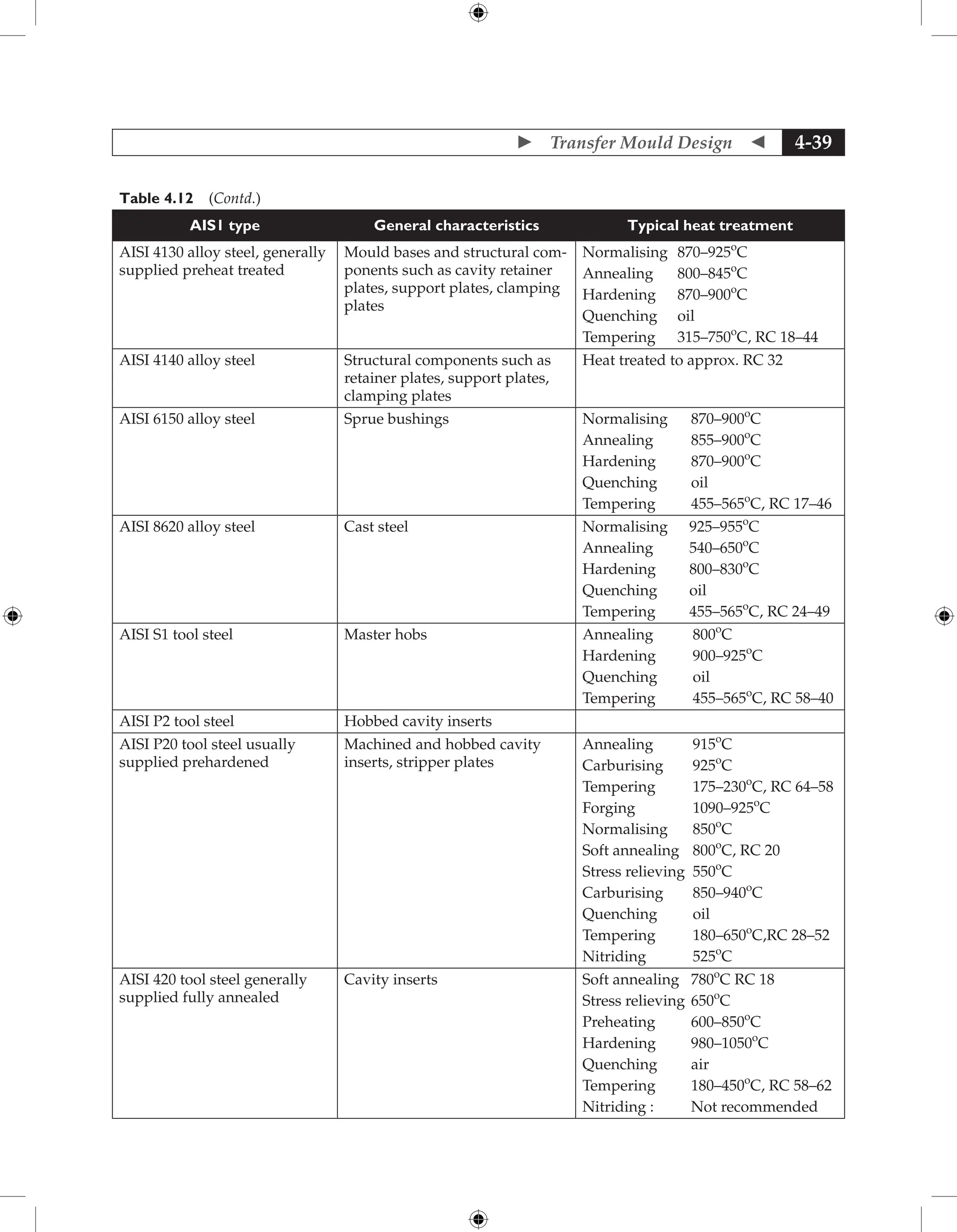

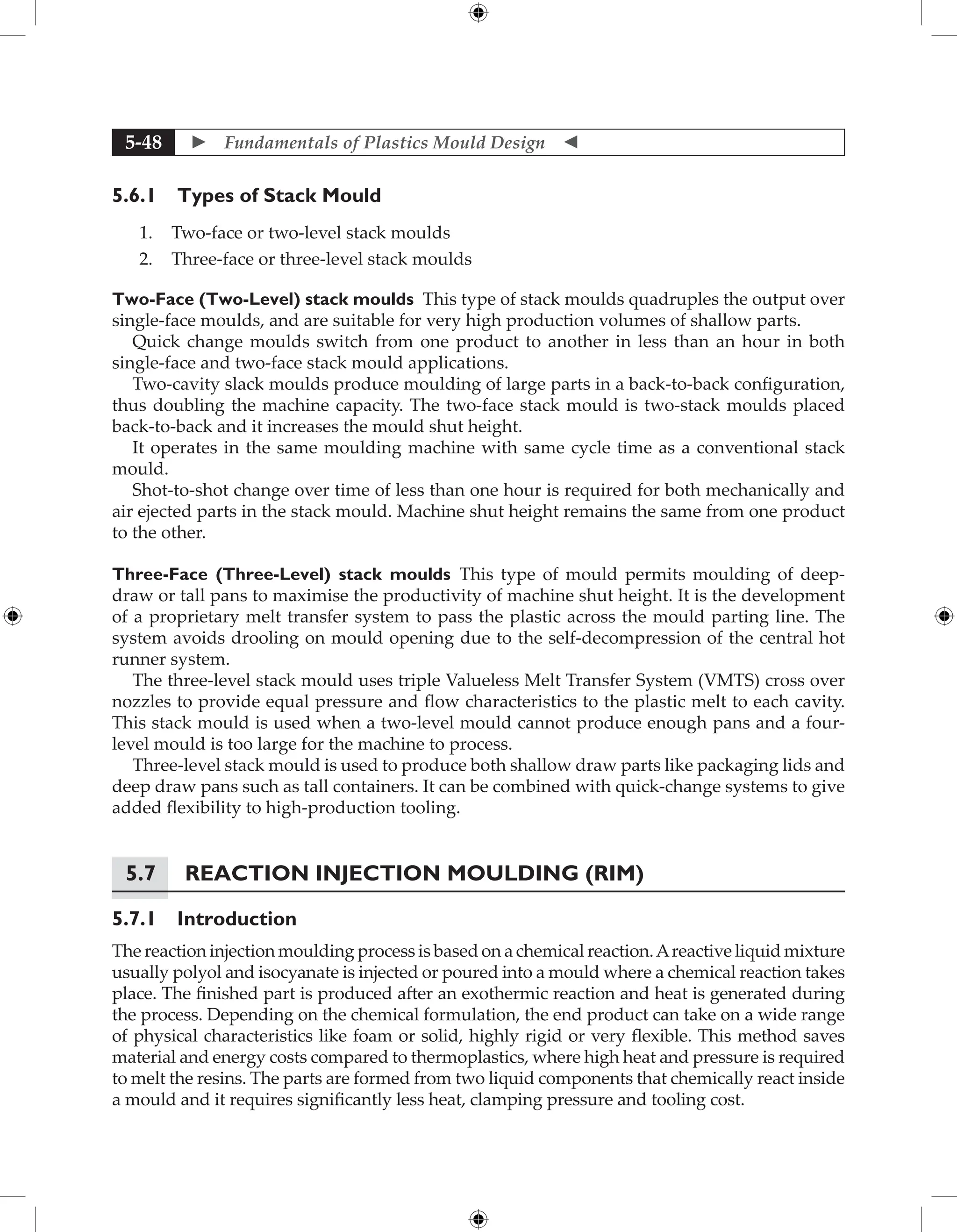

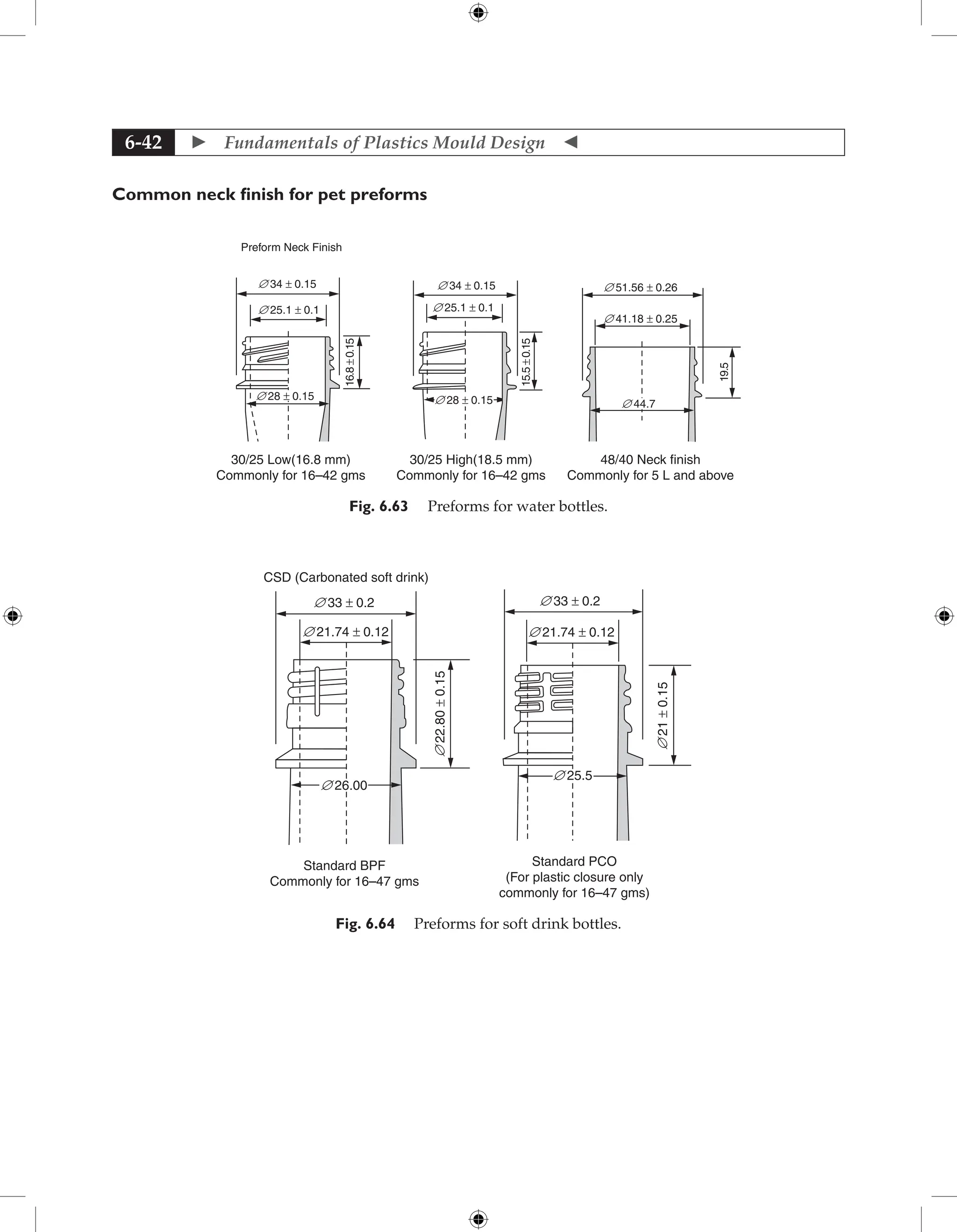

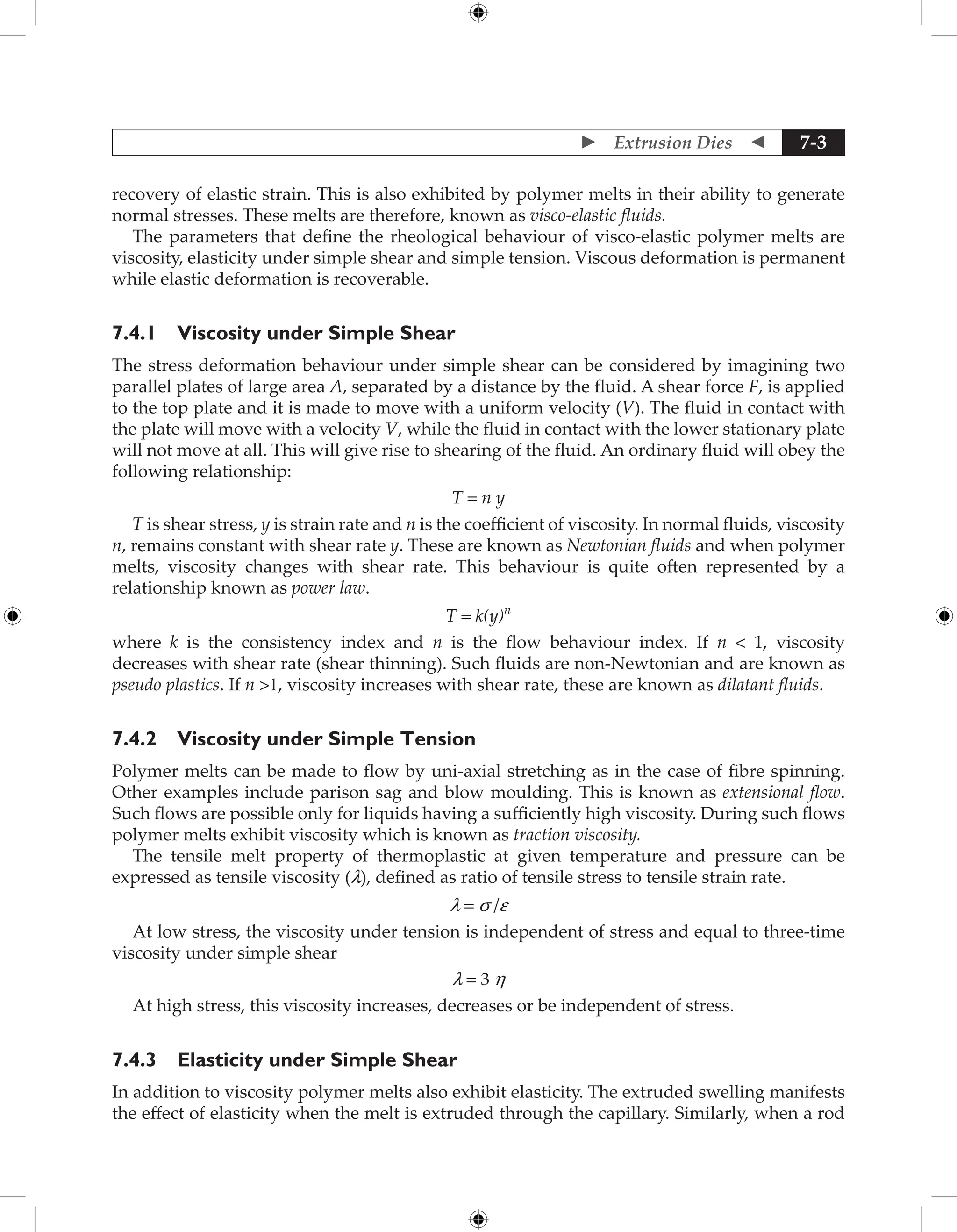

Fig. 1.157 Allowable unit load versus revolutions to failure by flexural fatigue (fluctuating tooth bending

stress). For unfilled, acetal copolymer Celcon gear with steel pinion and initial grease lubrication. For Ex.

19.2, Lu = 182 lb/in at 107

cycles for a 32-pitch gear. (Hoechst Celanese Corp).

Kt = 7000/8800 = 0.80 at 100o

F

(See Table 1.8. Kt = 1.0 for metal gears)

KL = lubrication factor = 1.0 for initially lubricated pair (this case) = 1.5–3.0 for

continuous lubrication

Km = mating material factor = 1.0 for steel pinion, 32 m in rms surface finish or better

with friction coefficient of 0.15

Km = 0.75 for acetal-steel pair with friction coefficient of 0.35

Ks = tooth type factor = Ydes for design gear/Yref for reference gear

where Y = Lewis form factor: Yref = 0.52, 0.64, or 0.69 for 12, 24, or 32 diametral pitch

gears, respectively. Ydes is given in Table 1.10 for full-depth 20o

pressure angle gears. In

this example, with 80 teeth in the acetal gear, Ydes = 0.739 and Ks = 0.739/0.69 = 1.07.

Kg = gear type factor = 1.0 for spur, internal, and helical gears.

Cs = service factor = 0.80 (Table 1.10)

Combining these factors gives the predicted load to failure in 107 cycles from Eq. 2.2:

Lf = (182 × 0.80 × 1.0 × 1.0 × 1.07)/0.80 = 195 lb/in

which is 348% greater than the applied unit load of 56 lb/in.

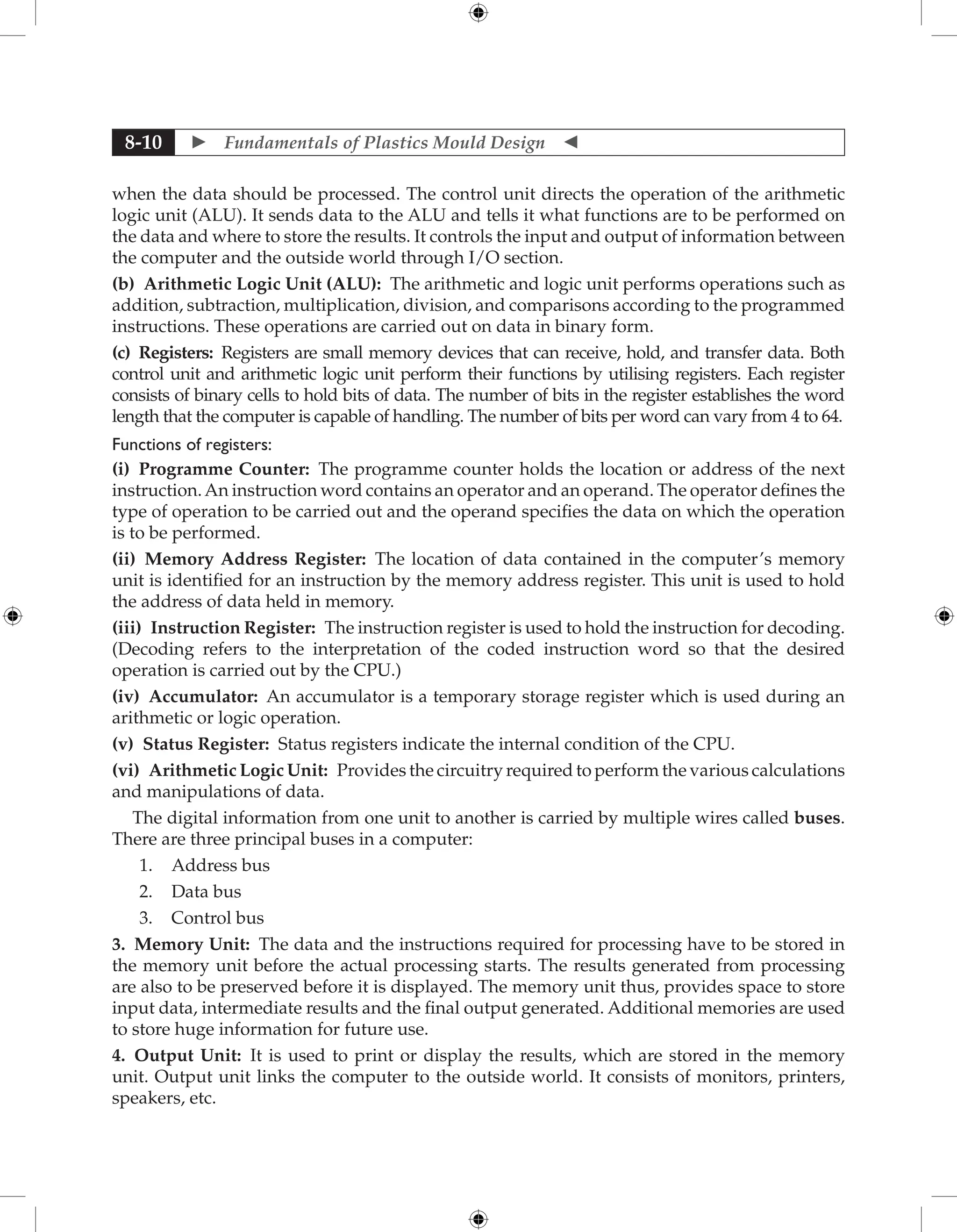

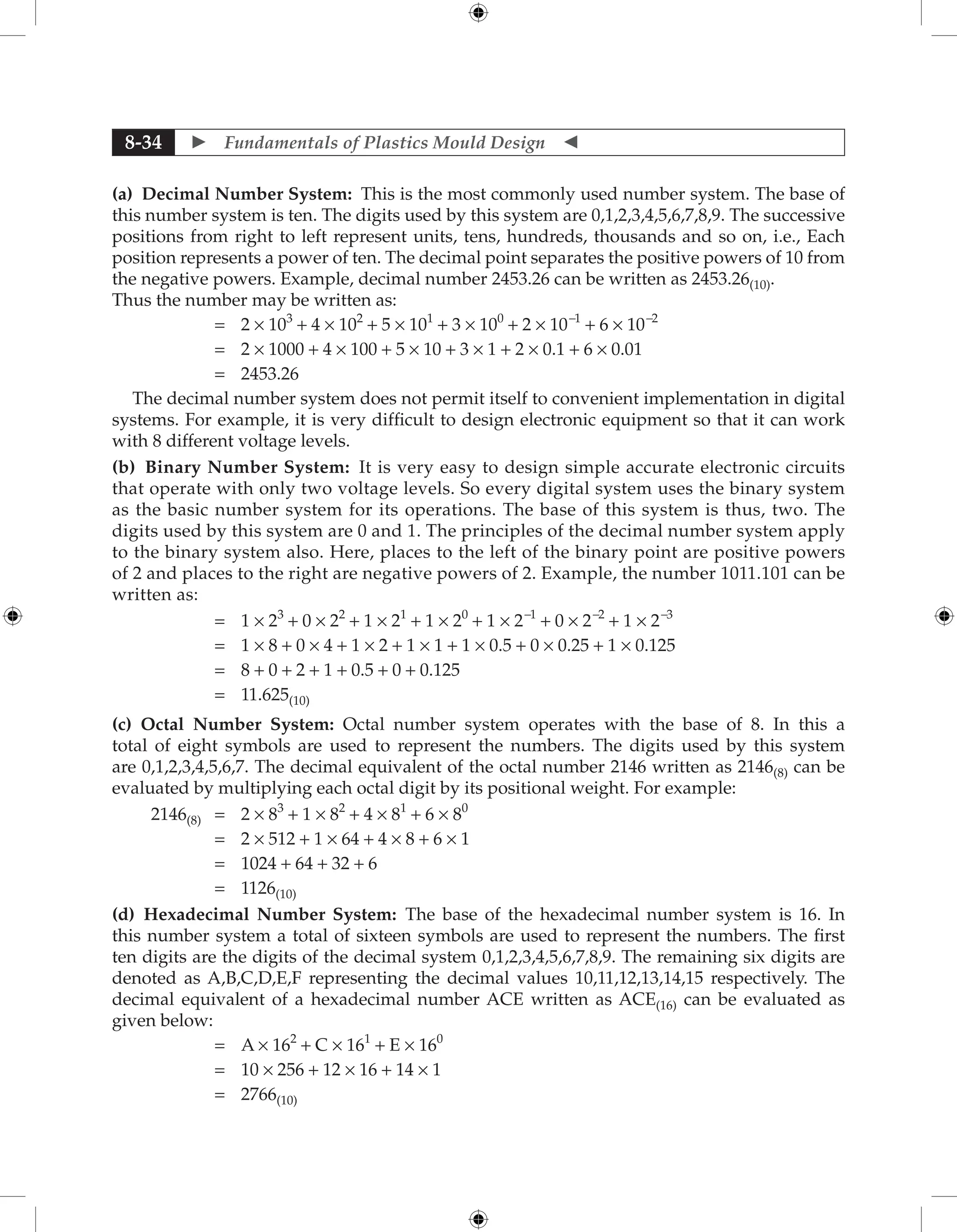

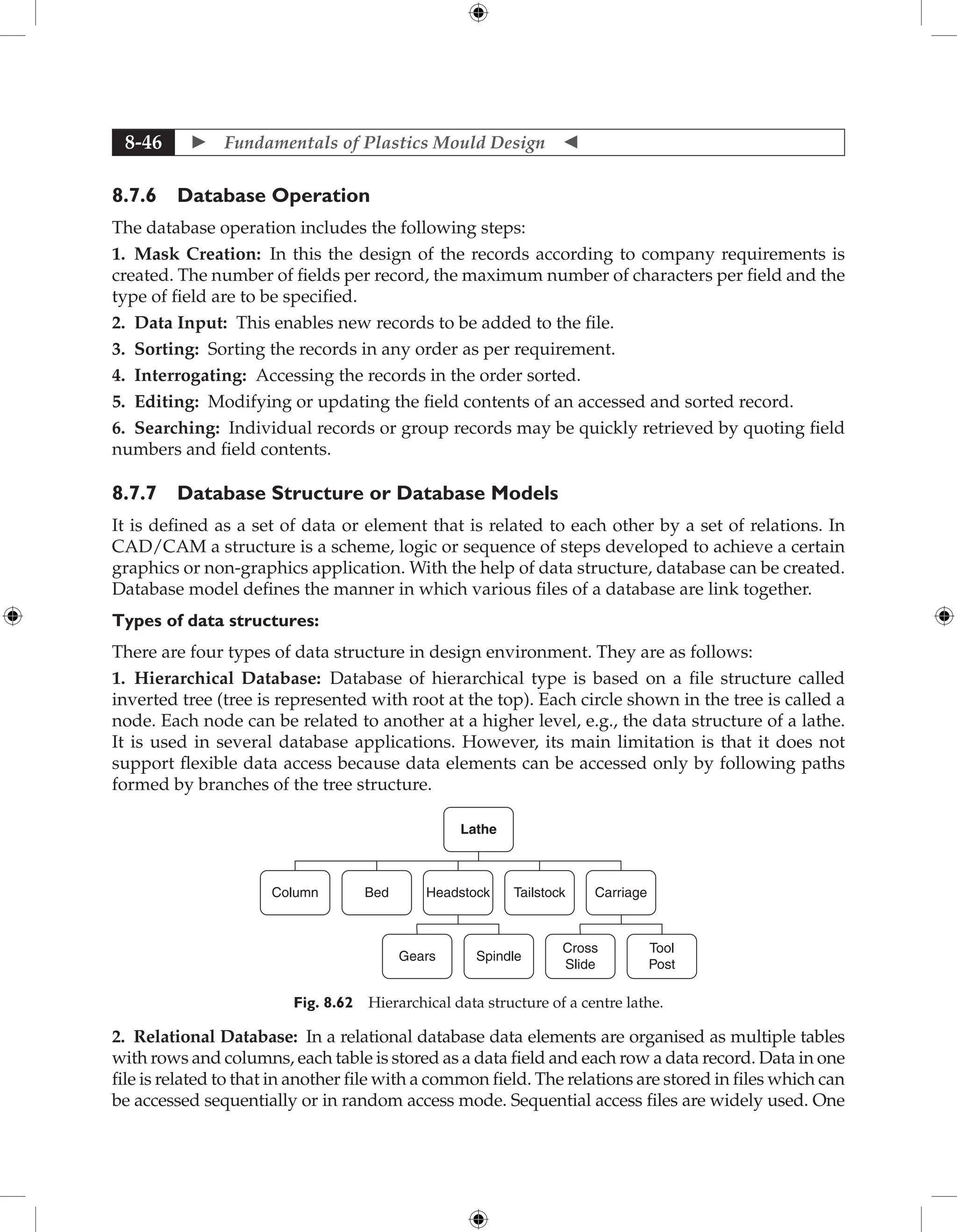

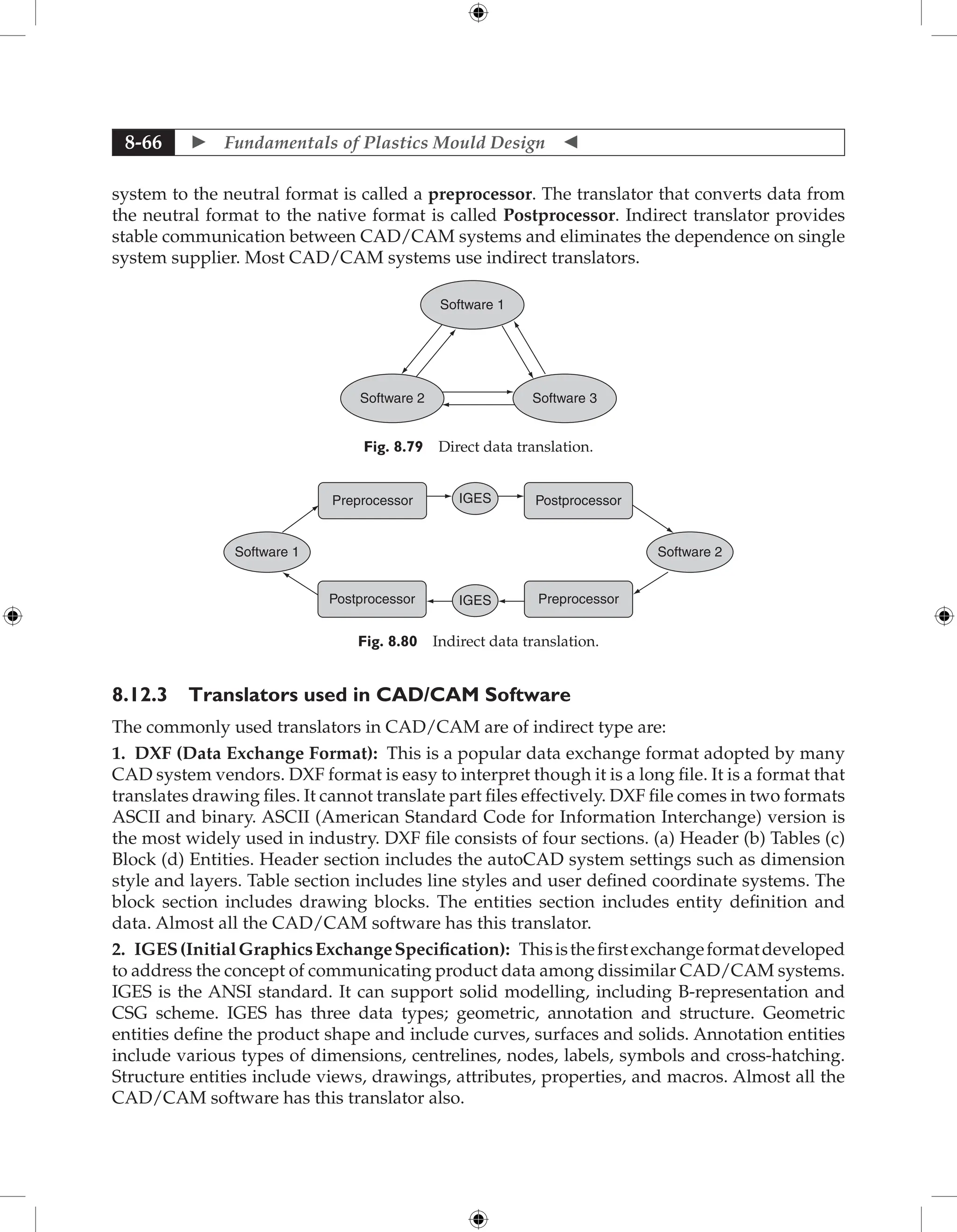

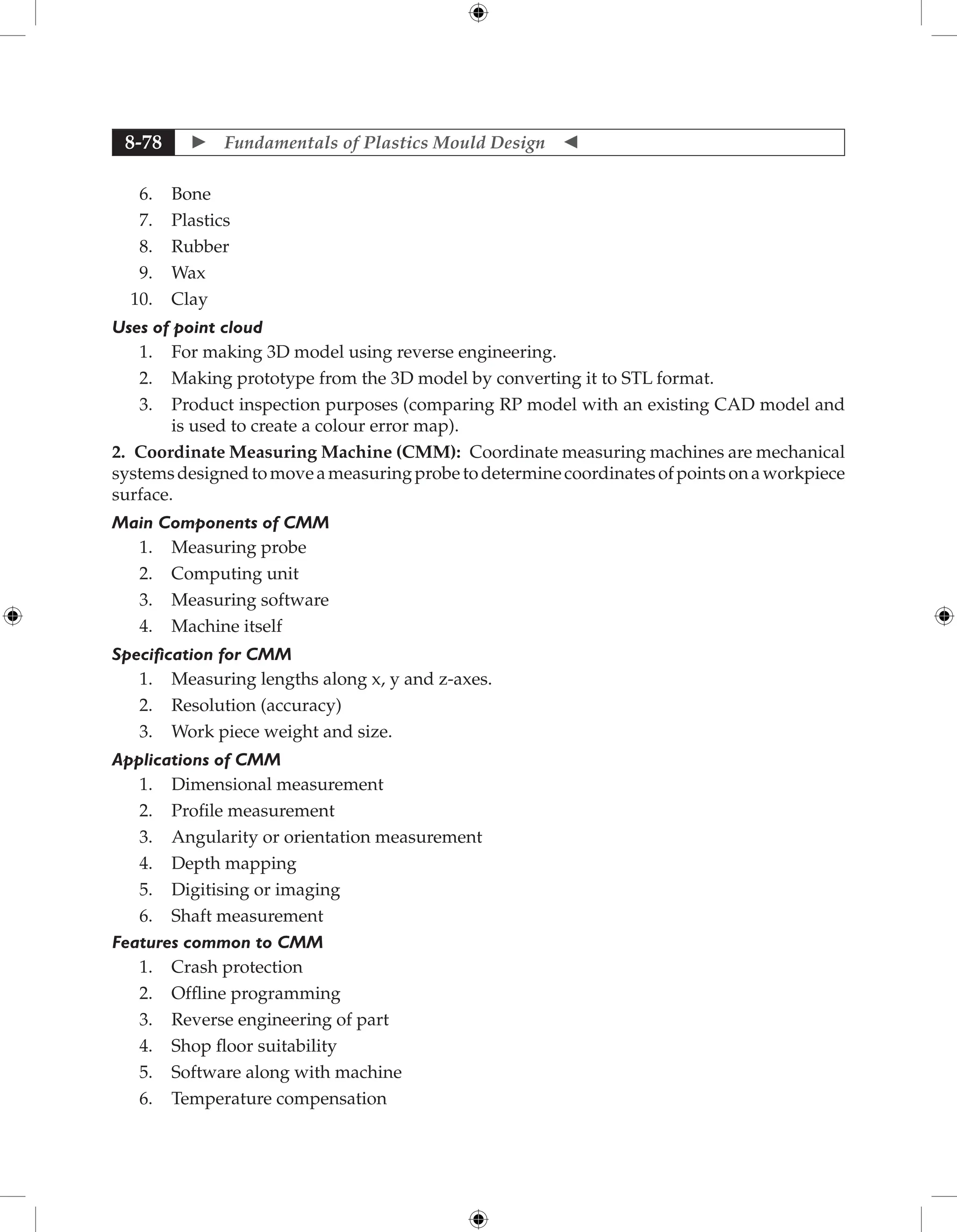

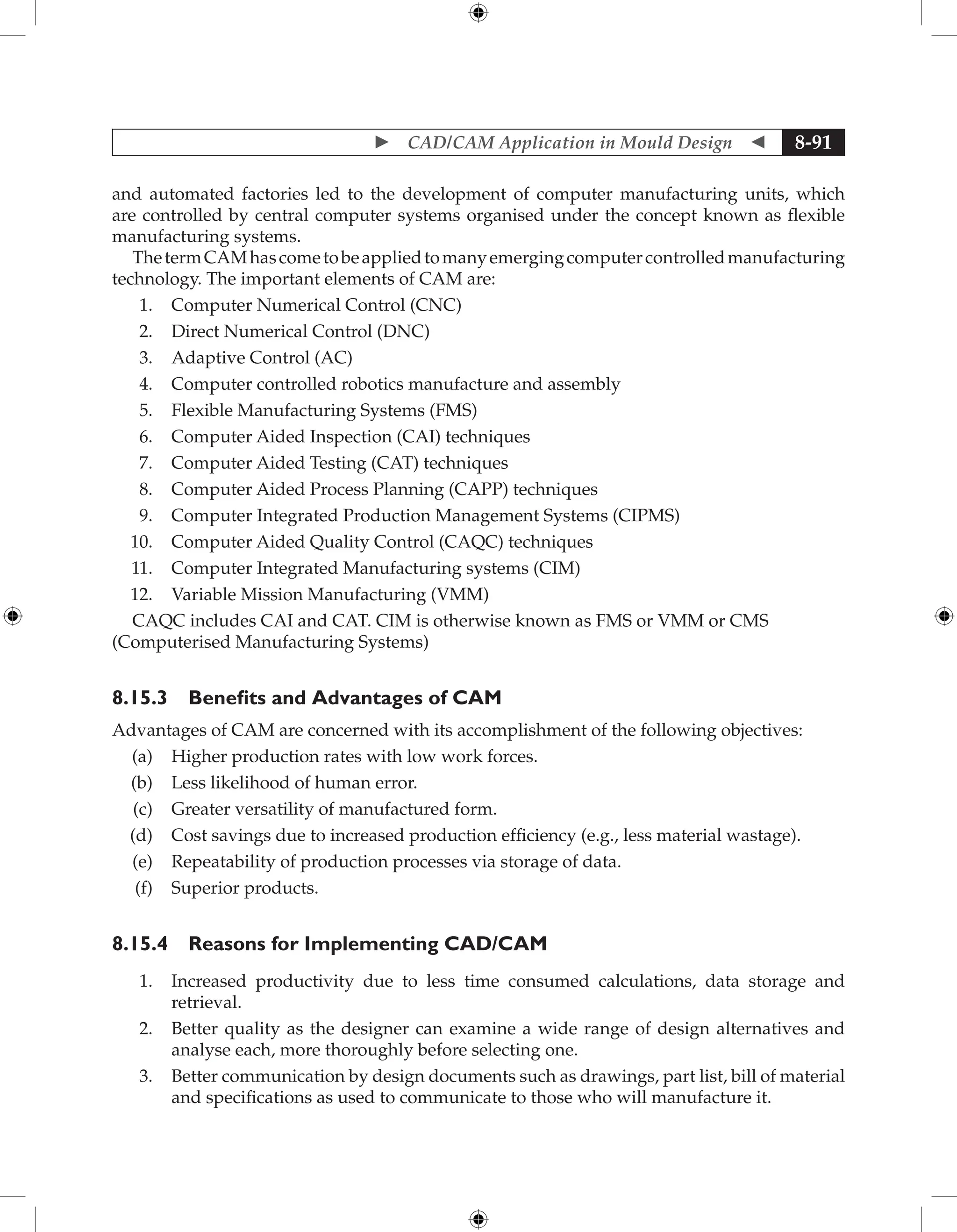

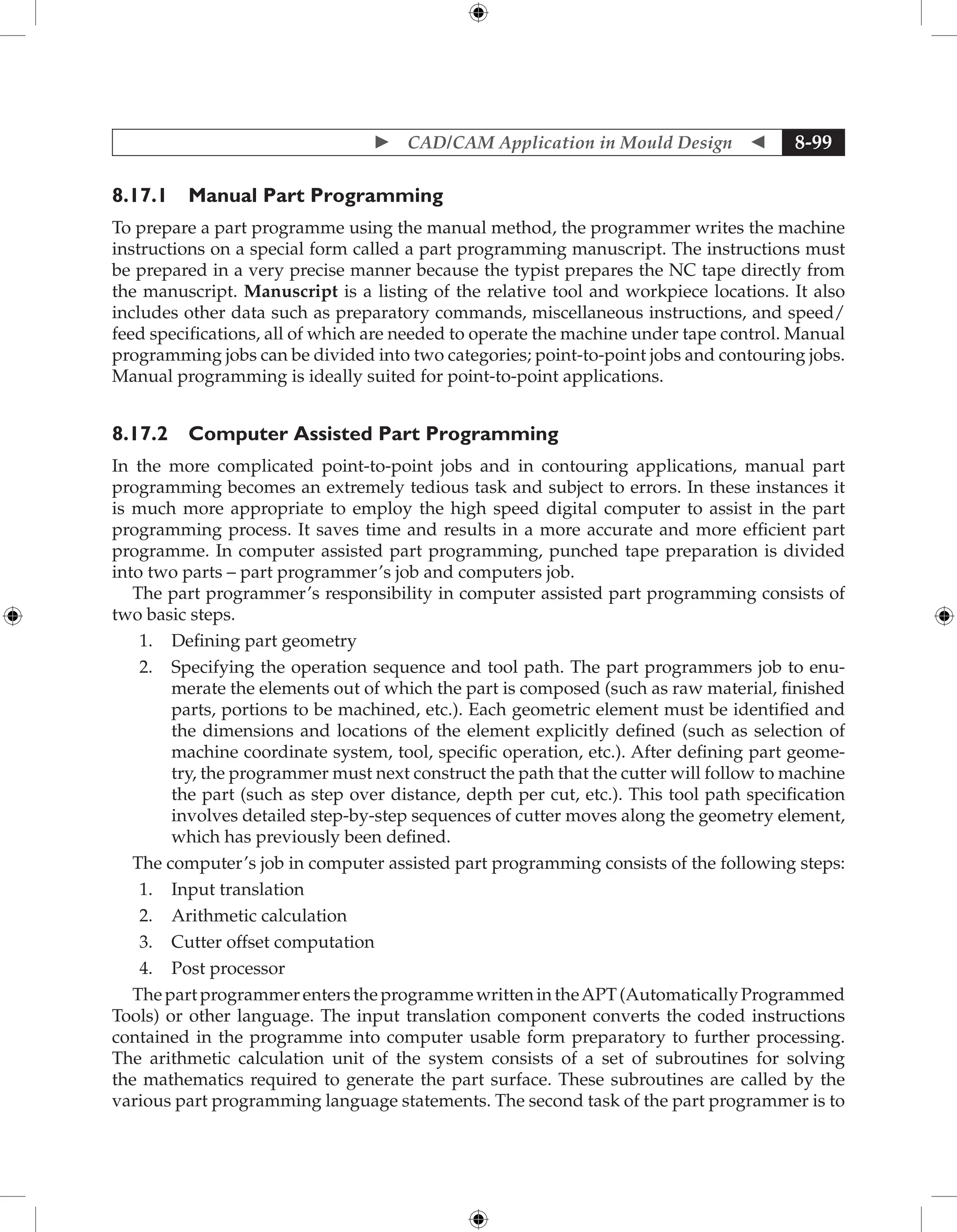

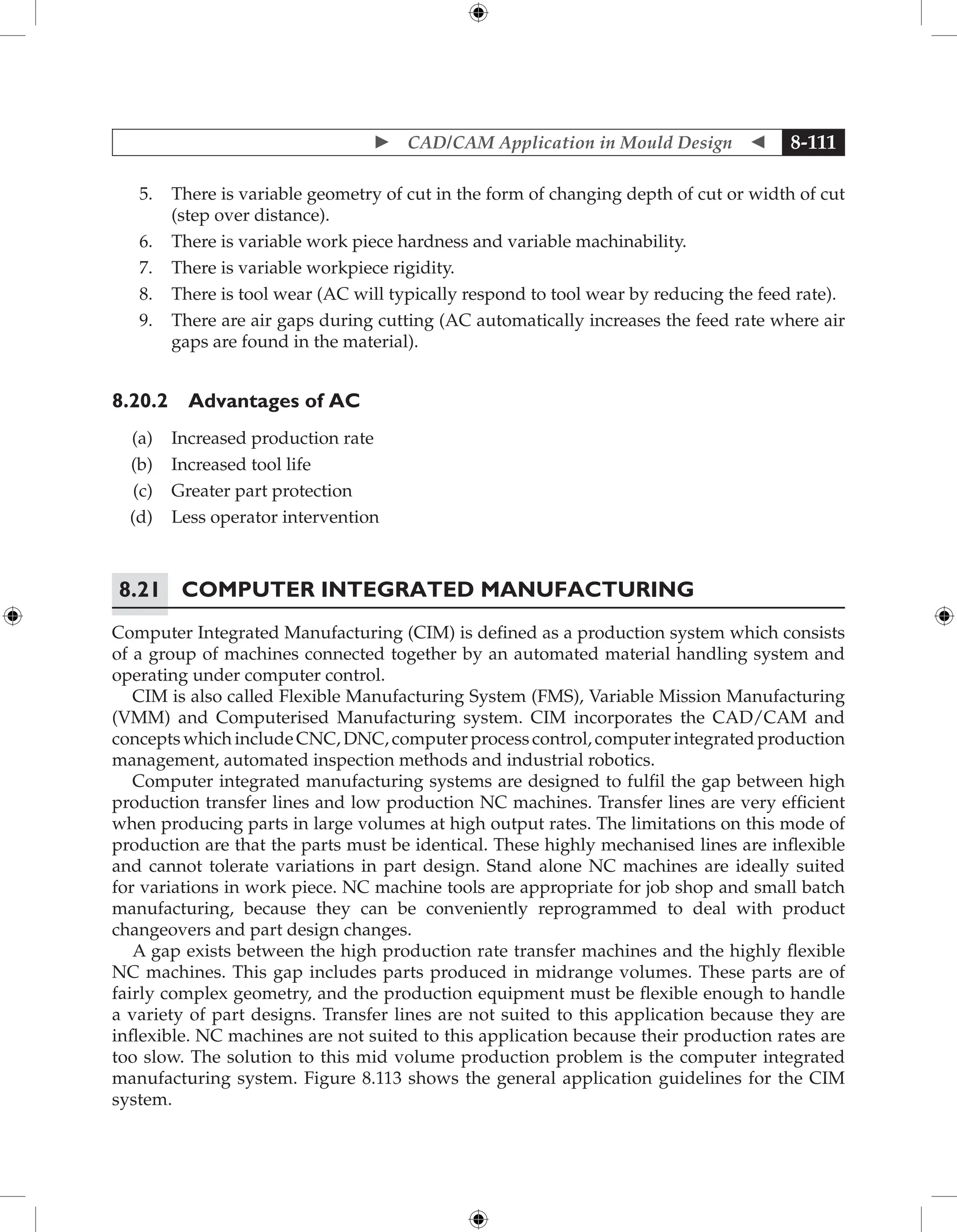

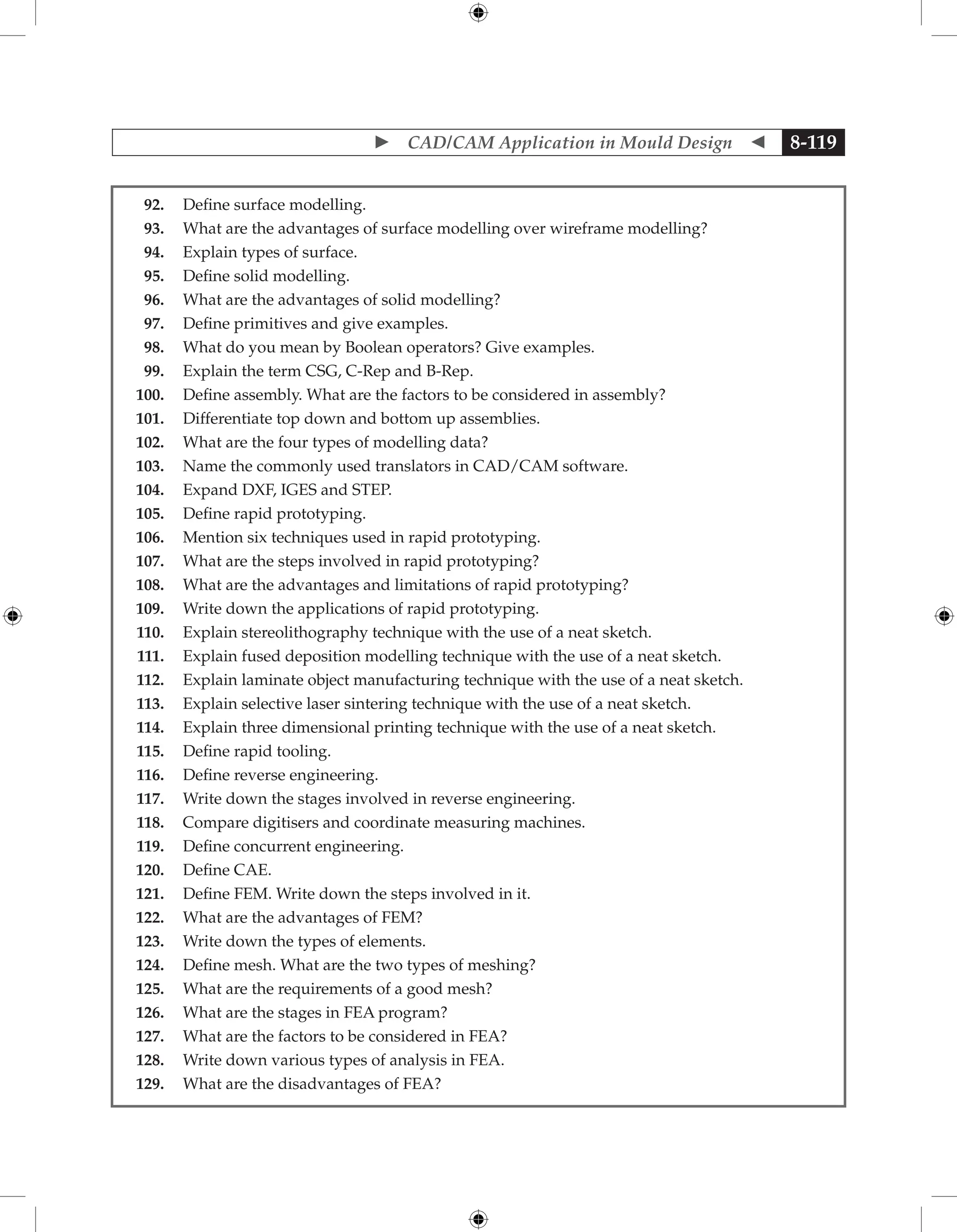

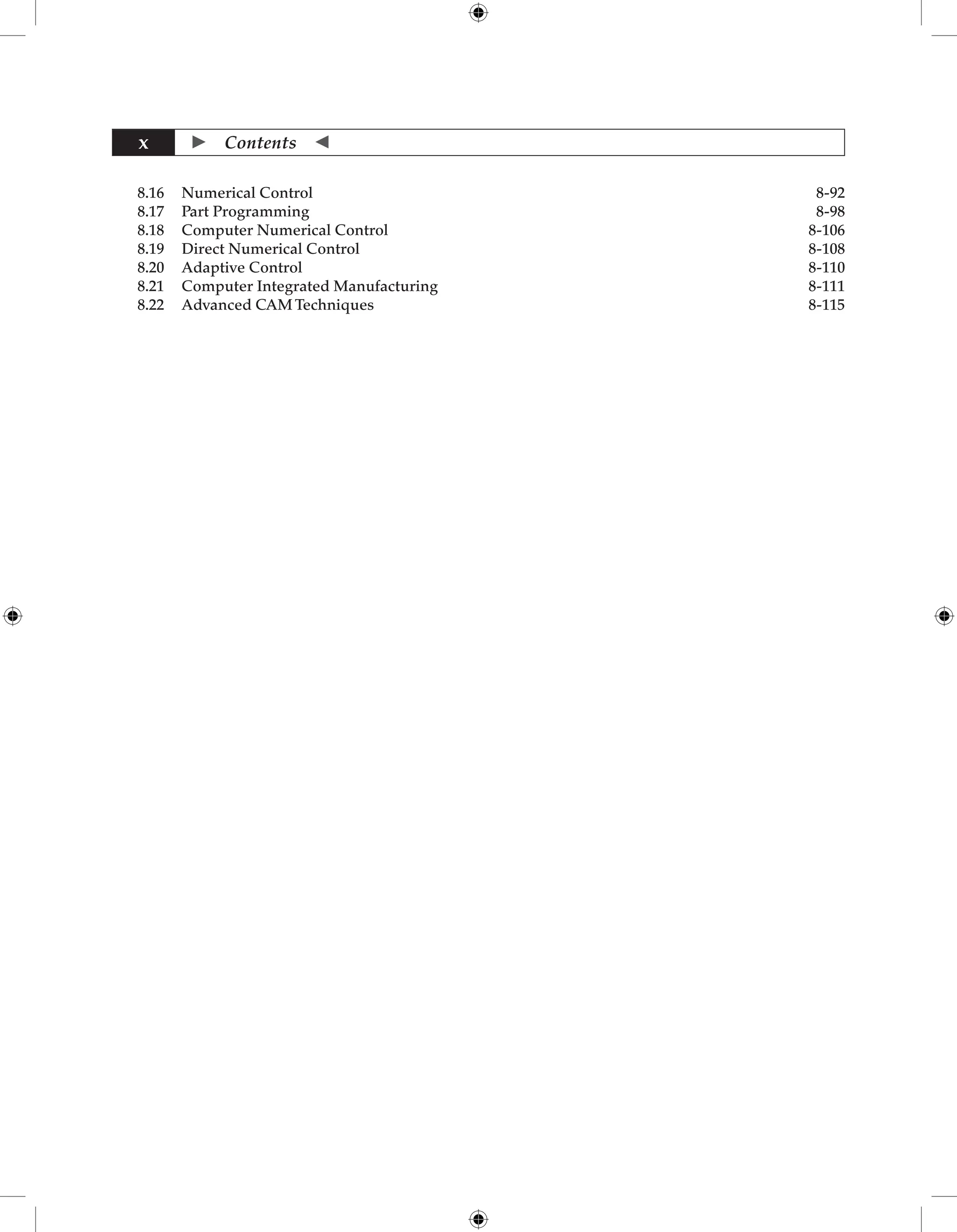

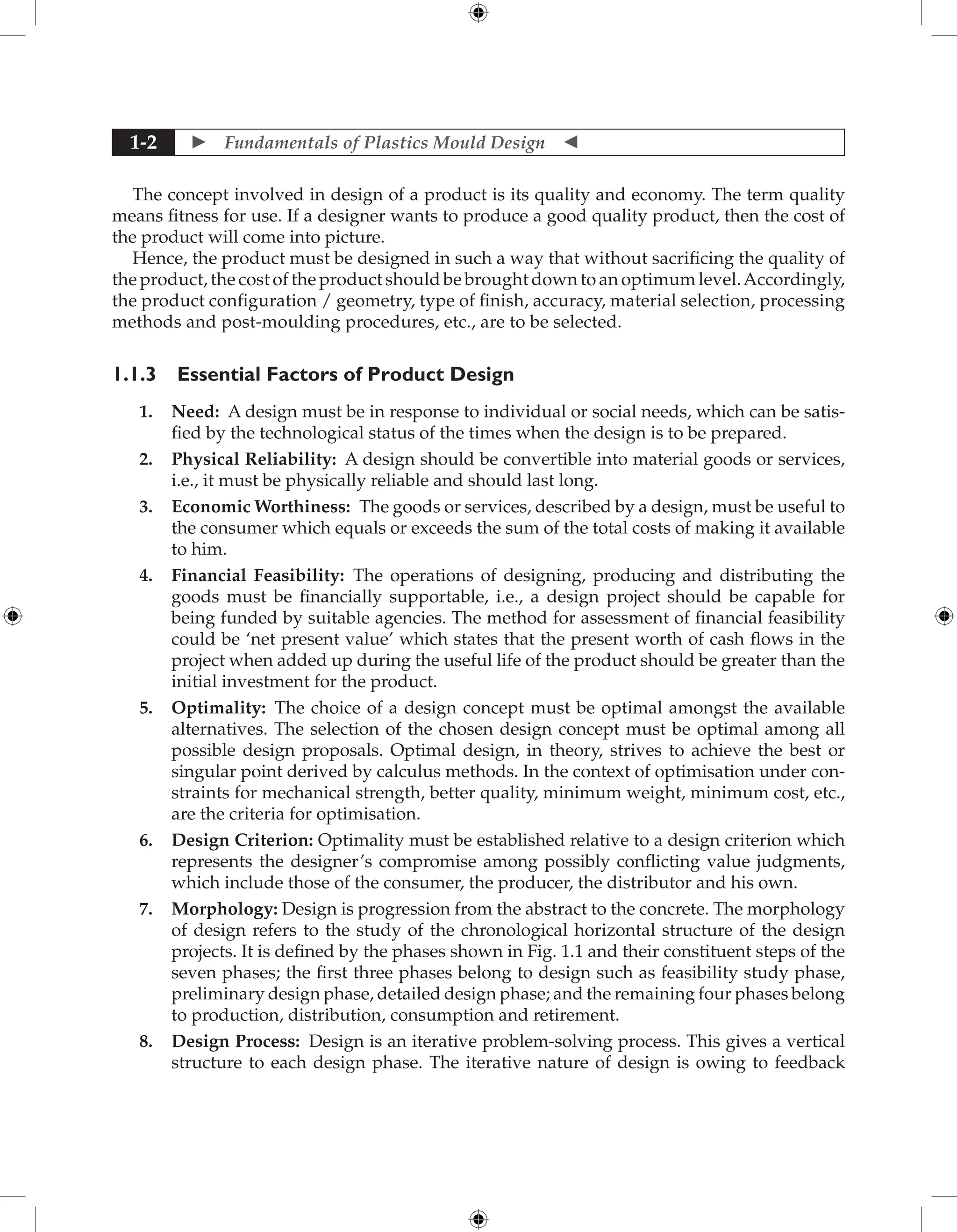

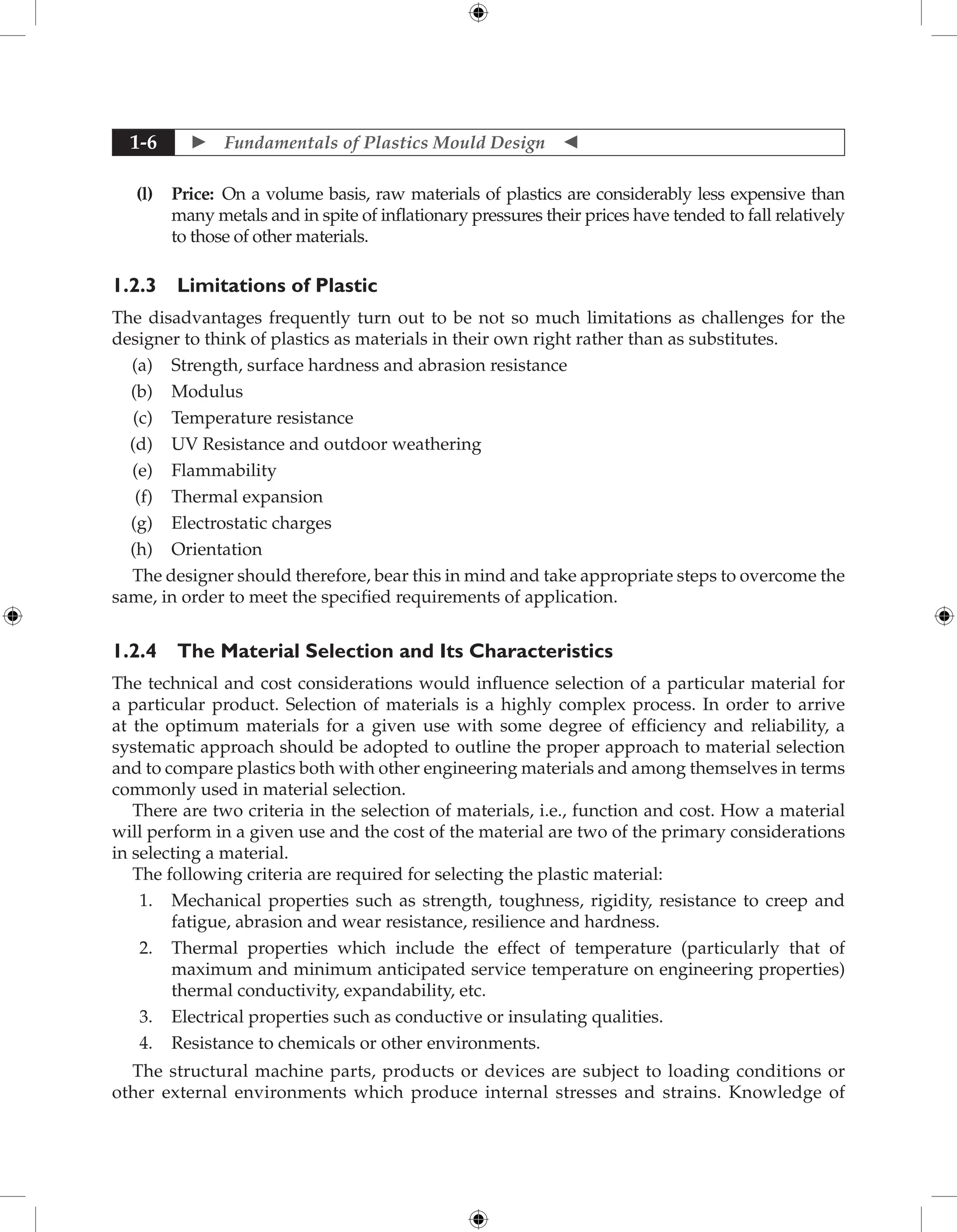

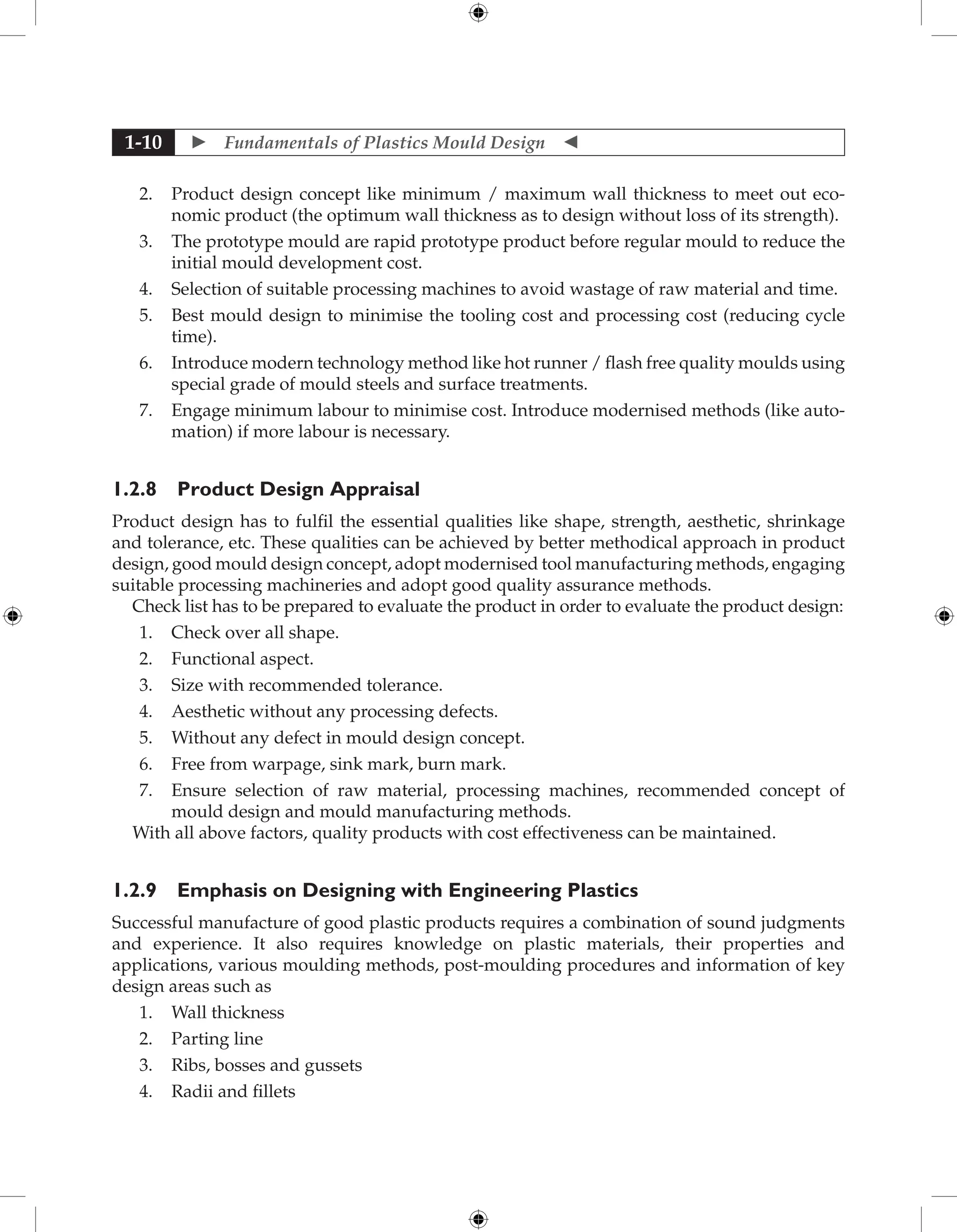

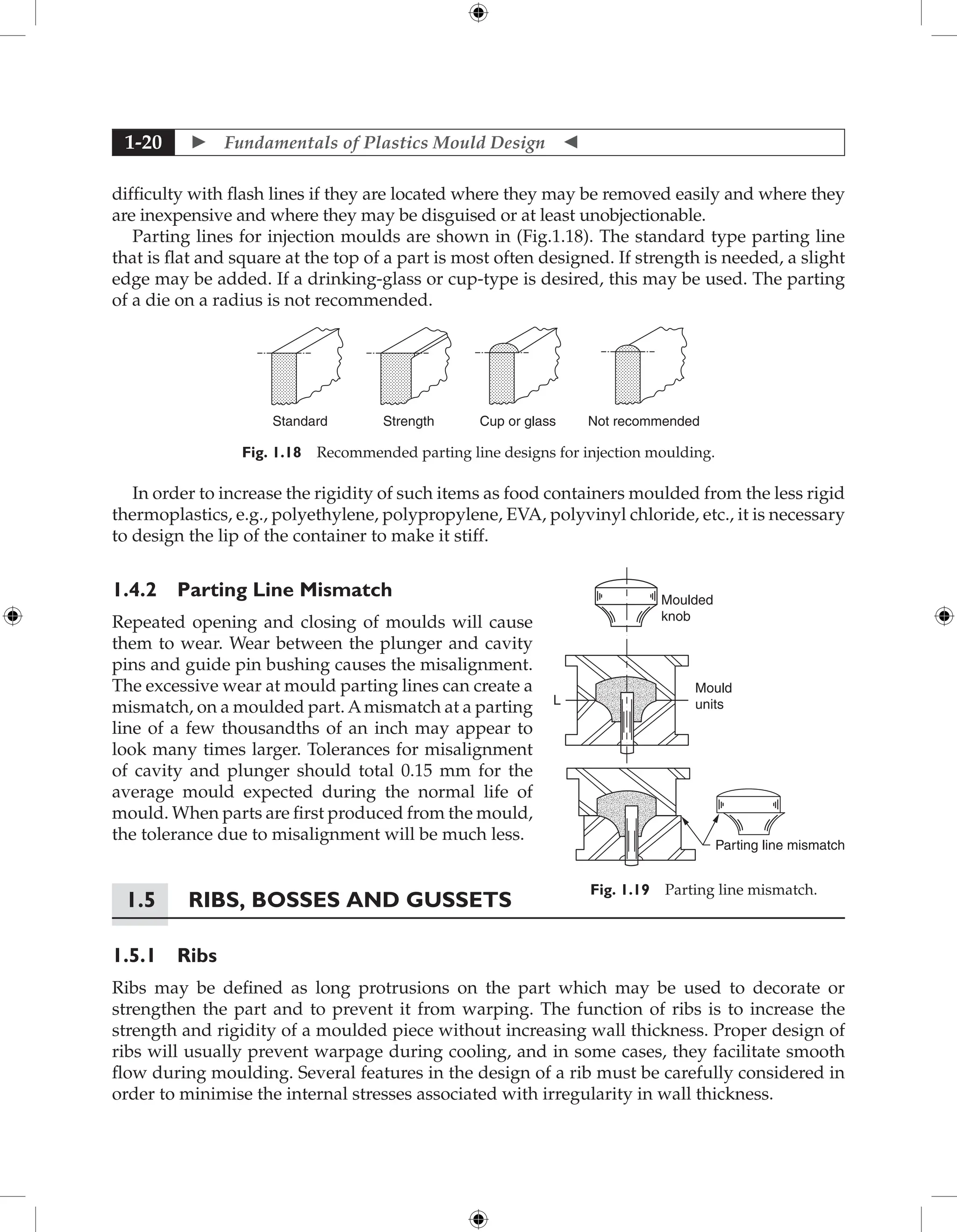

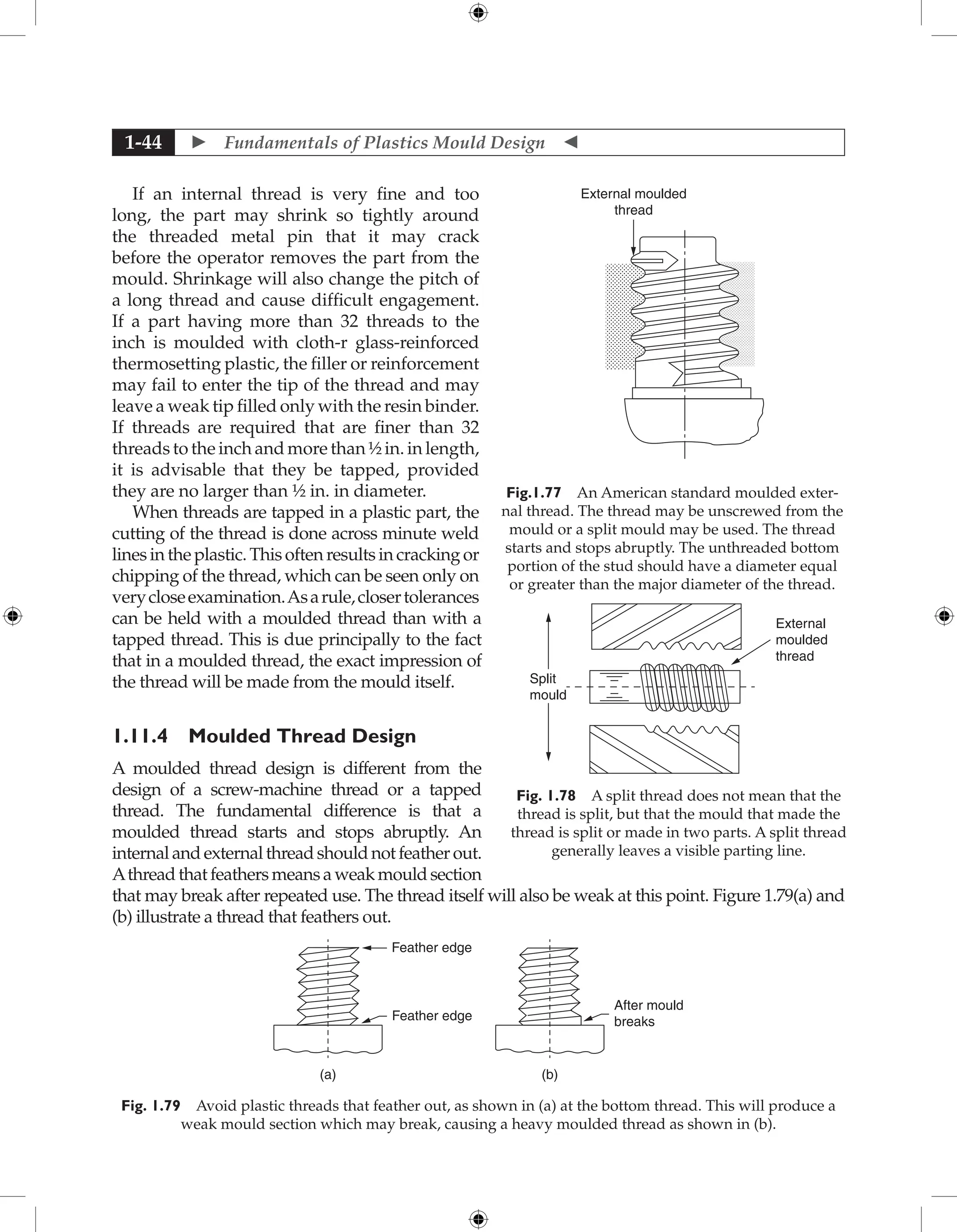

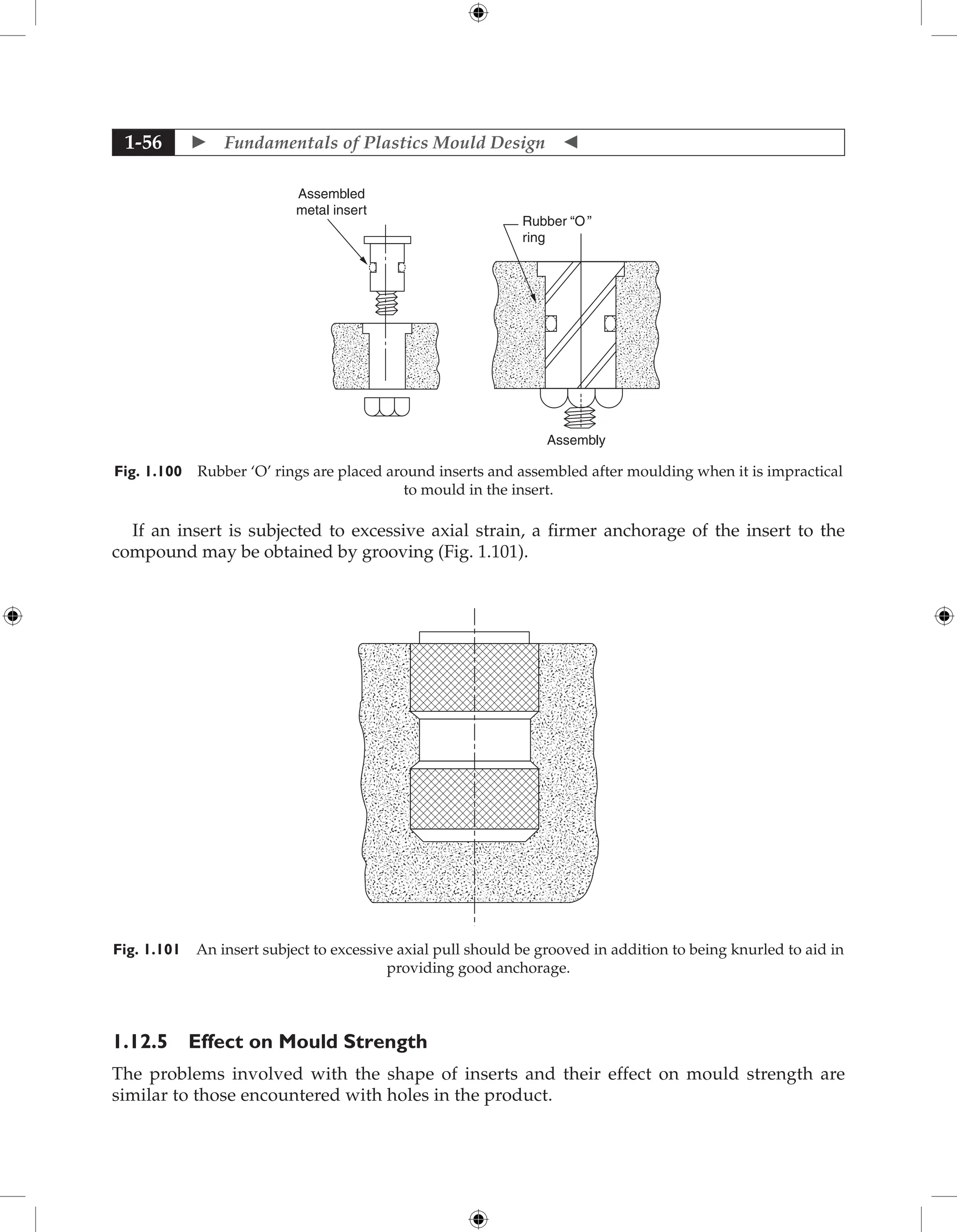

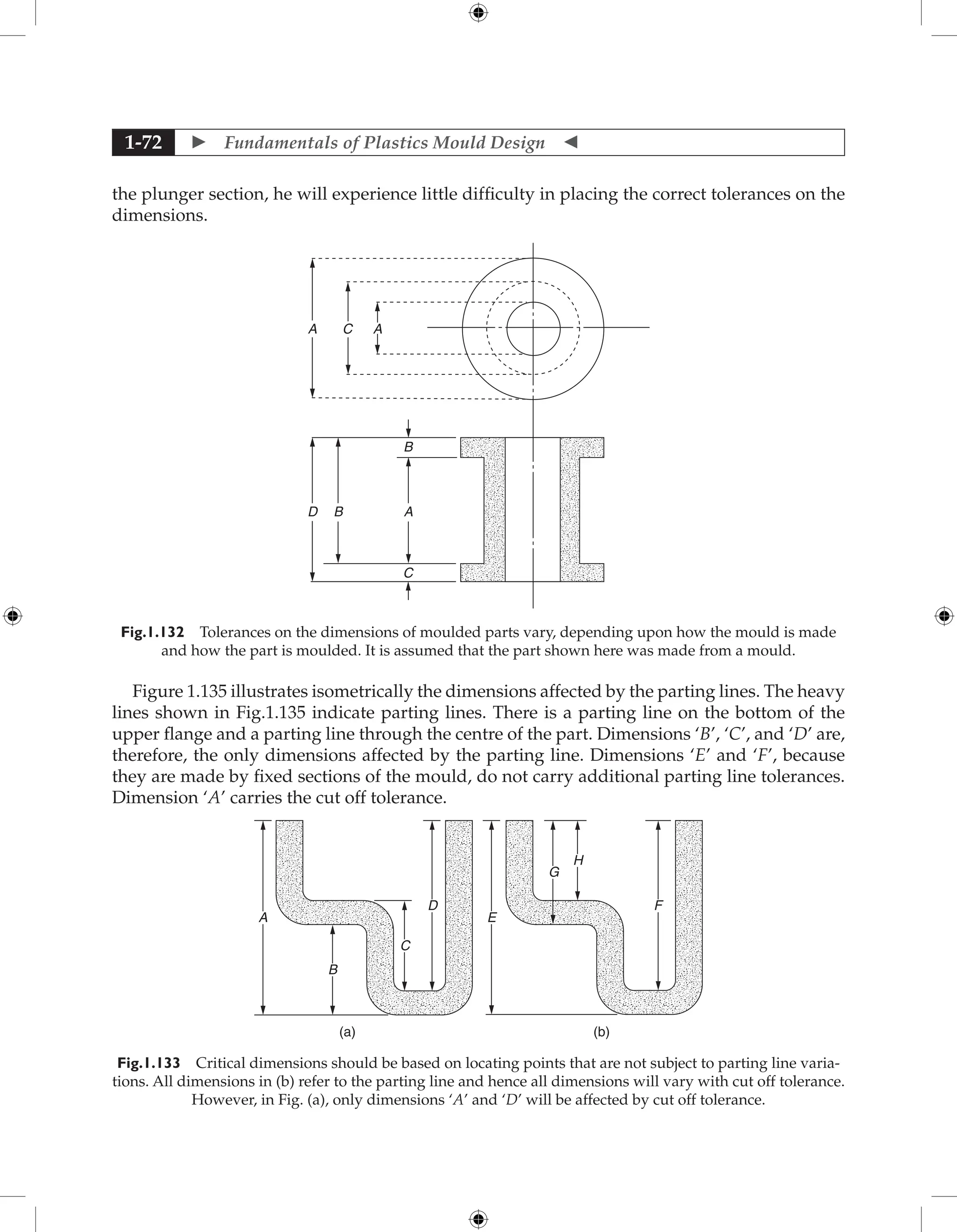

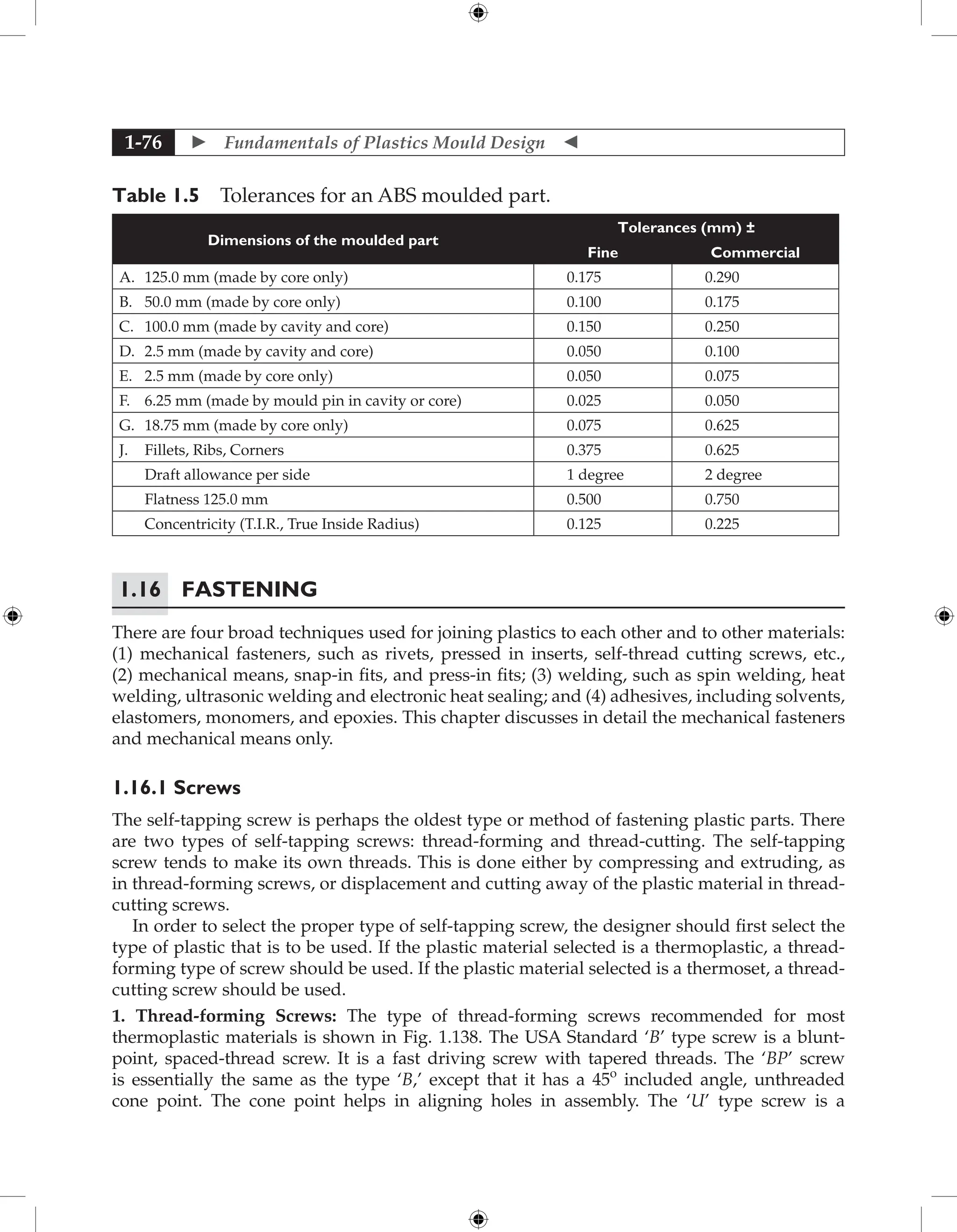

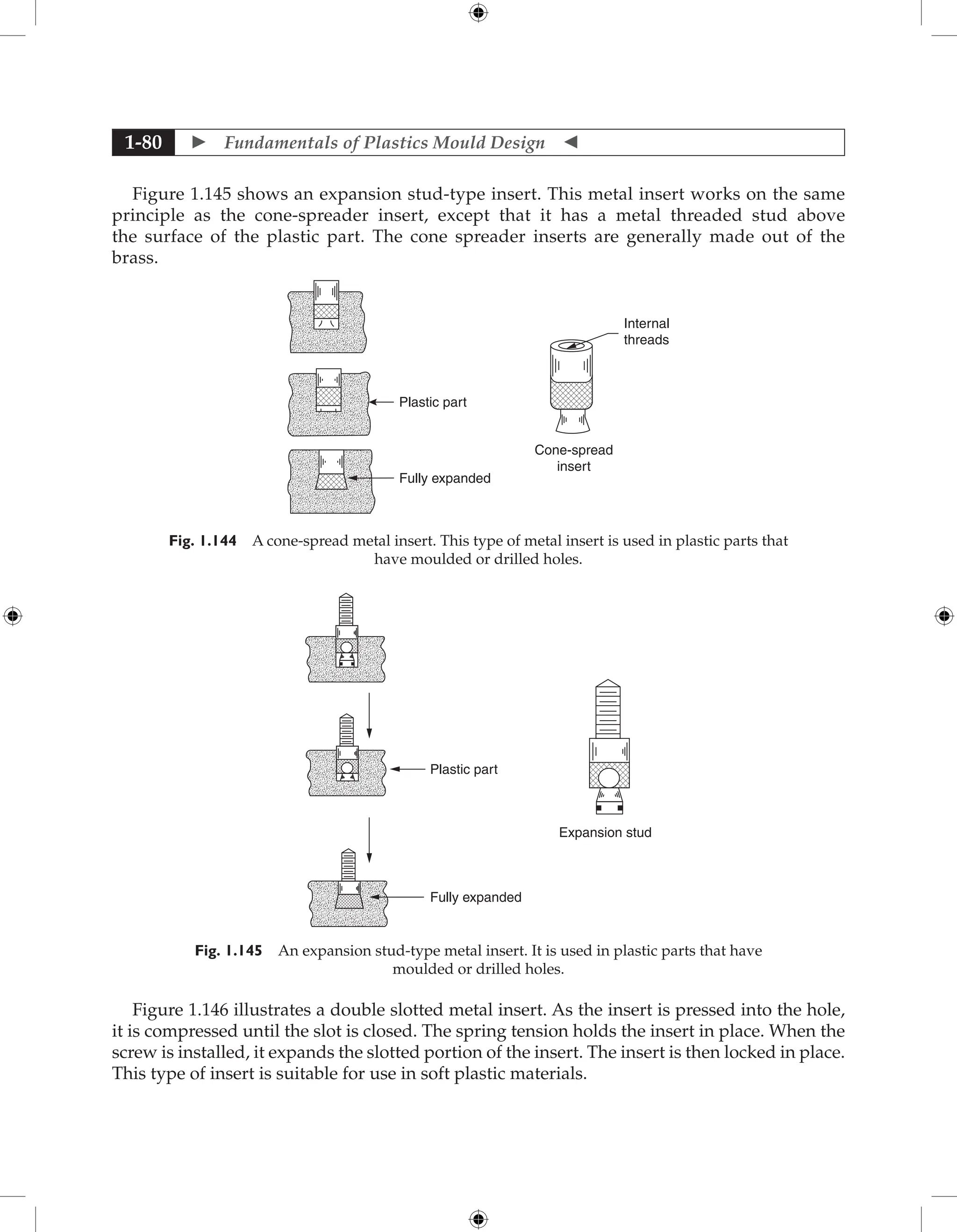

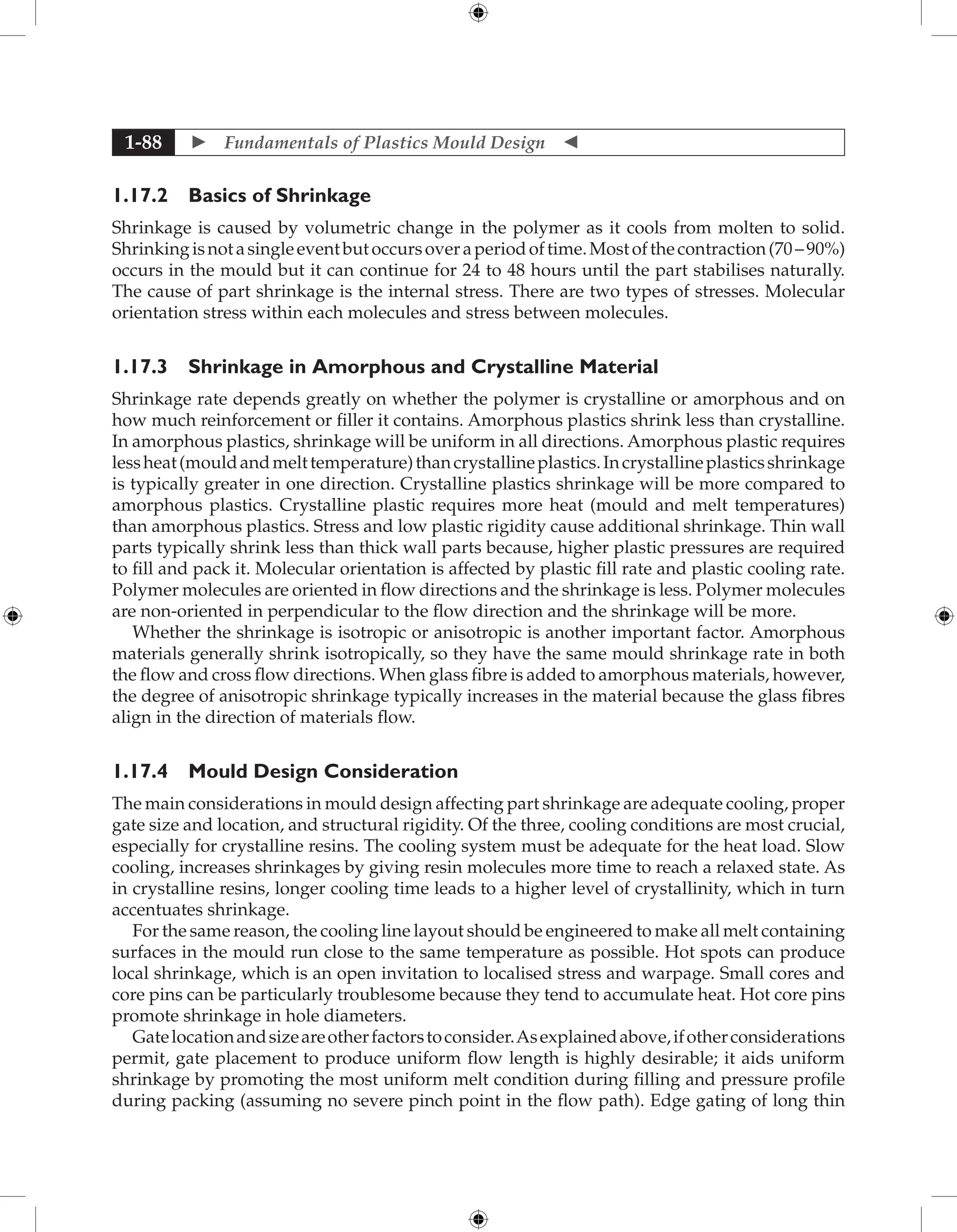

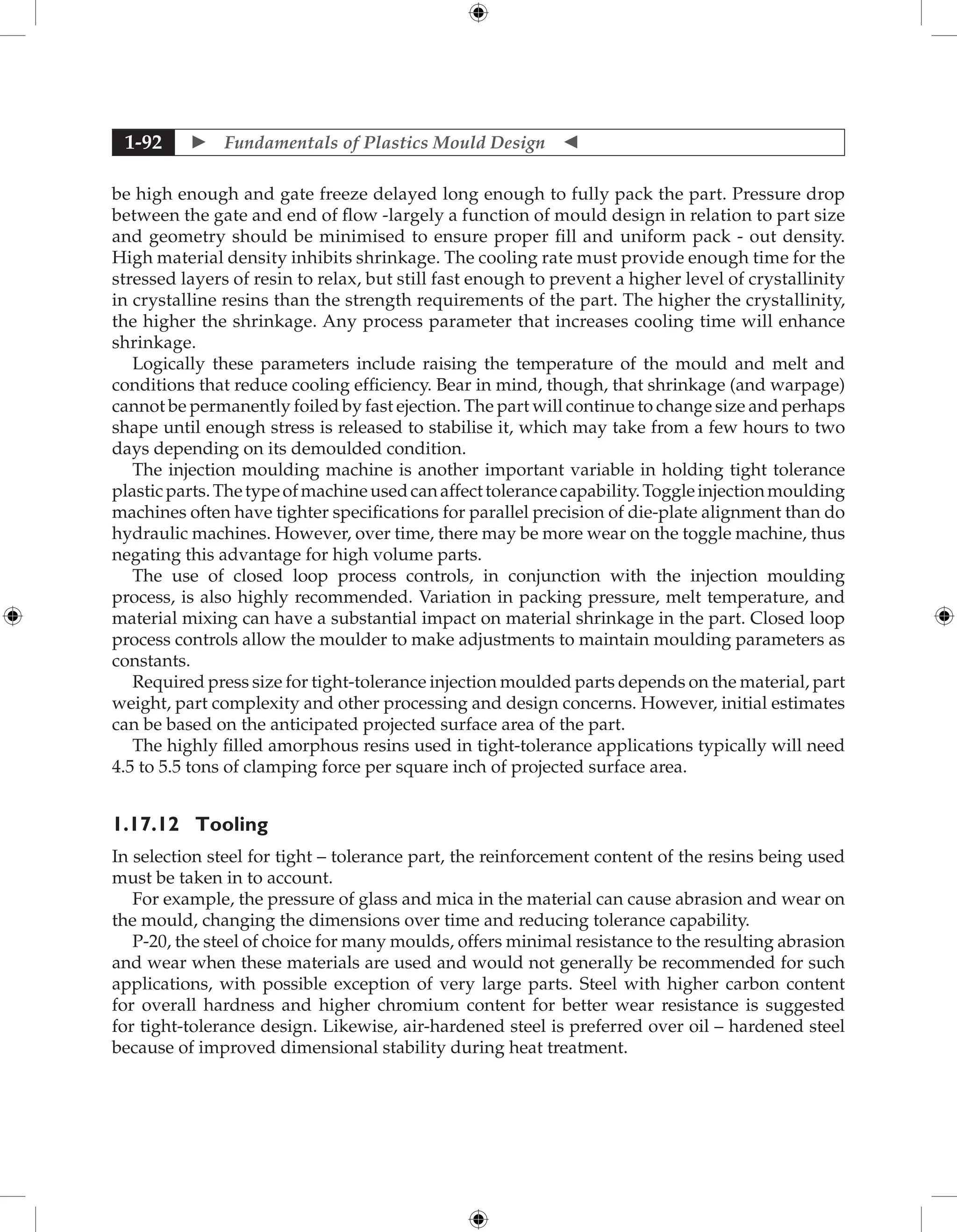

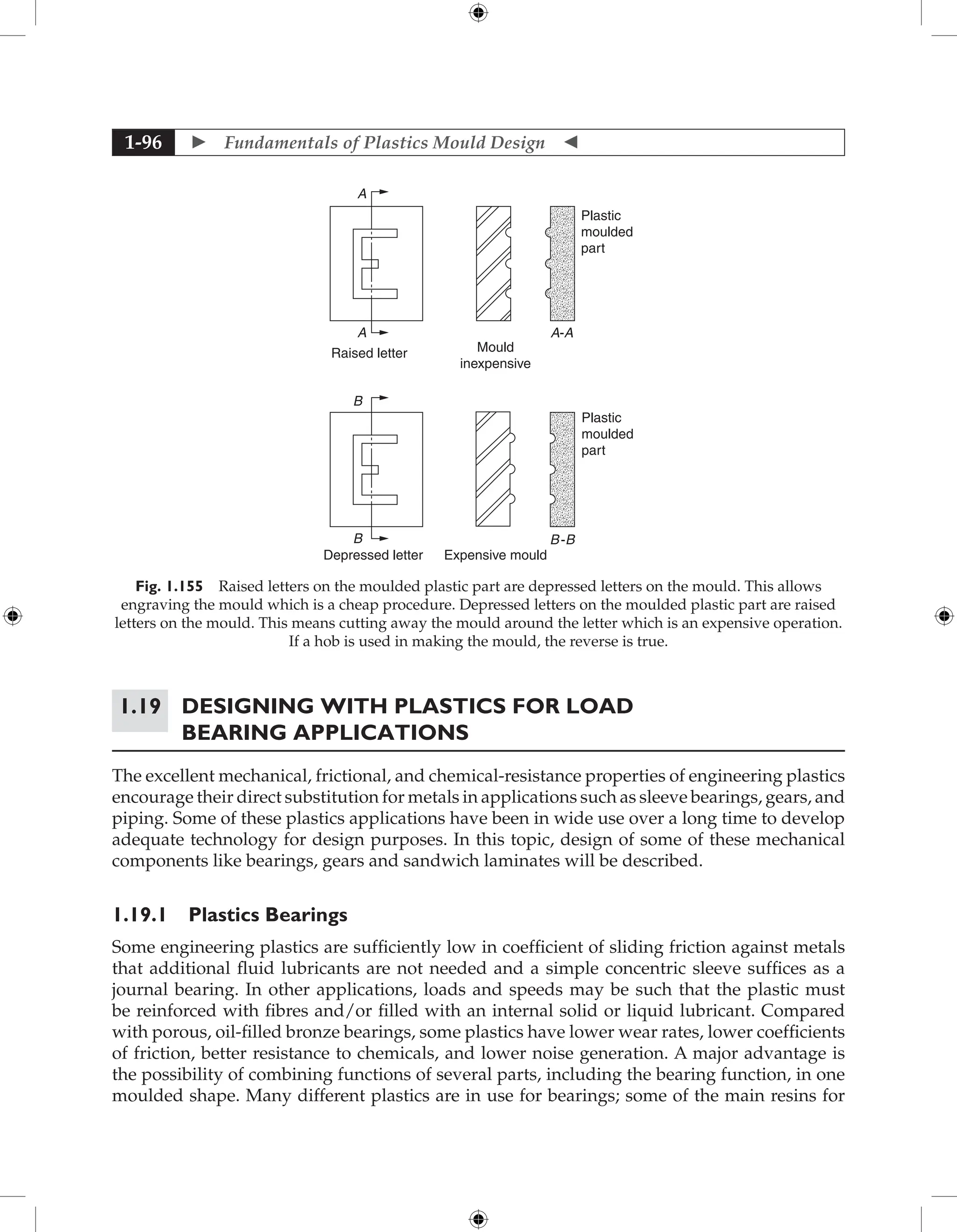

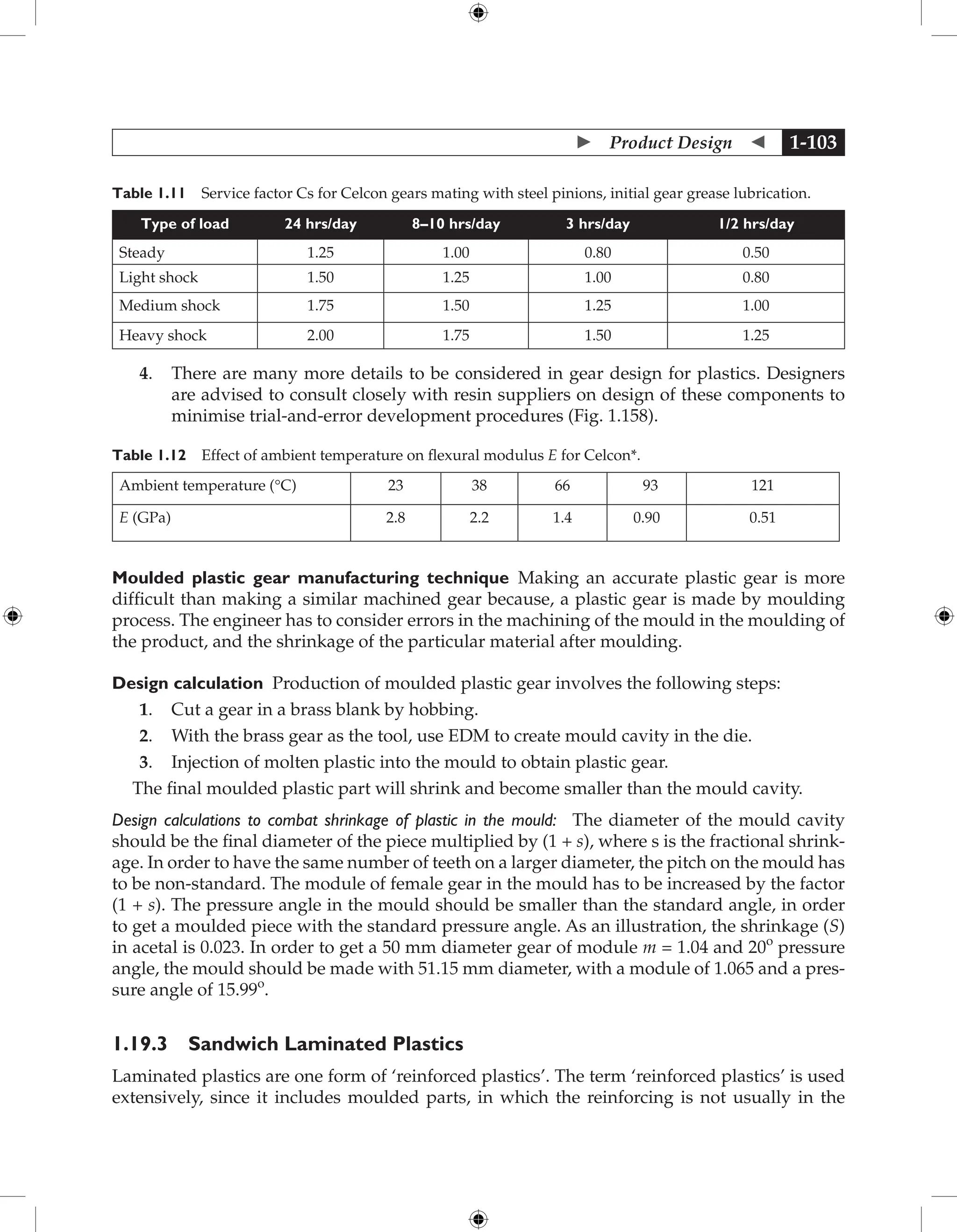

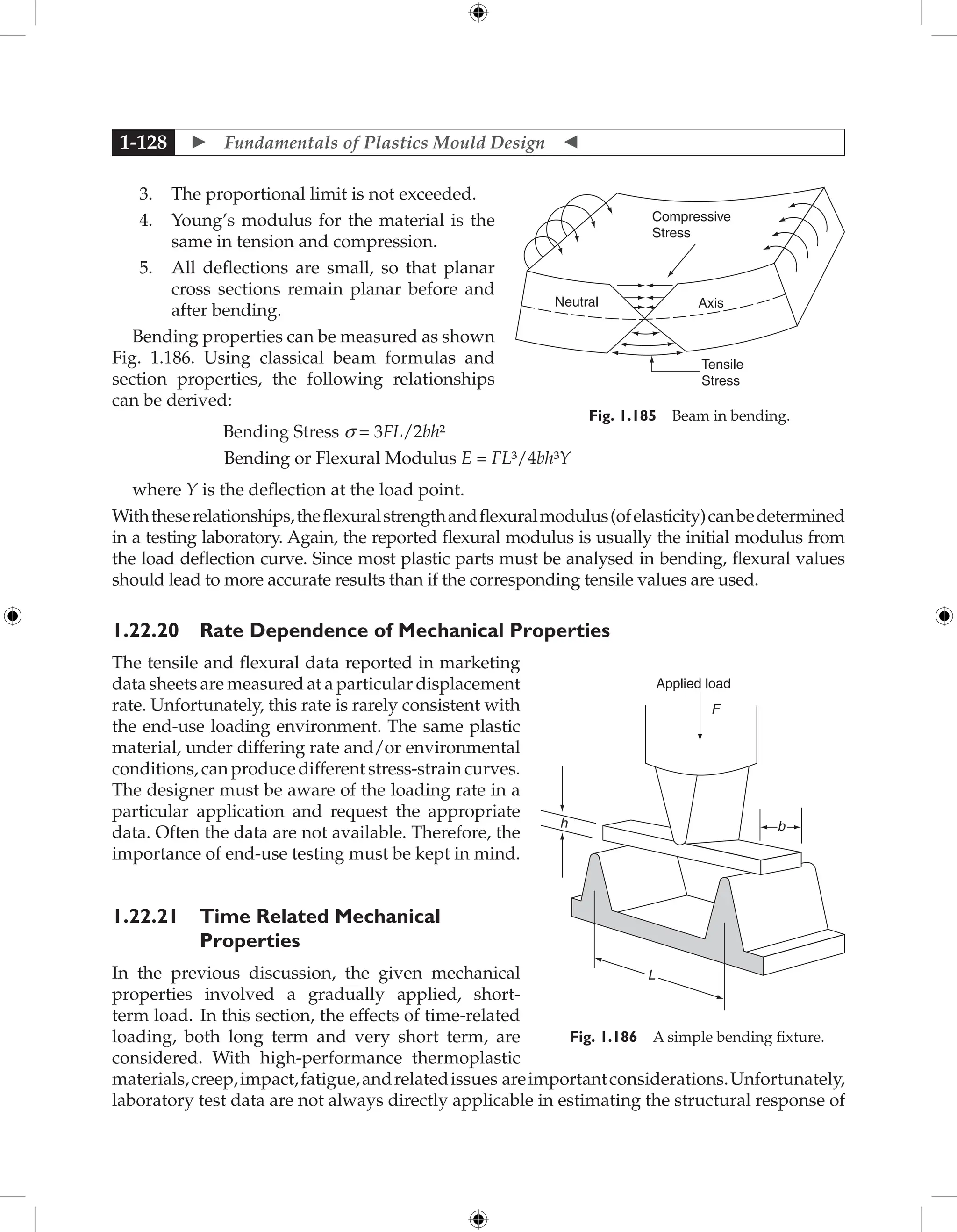

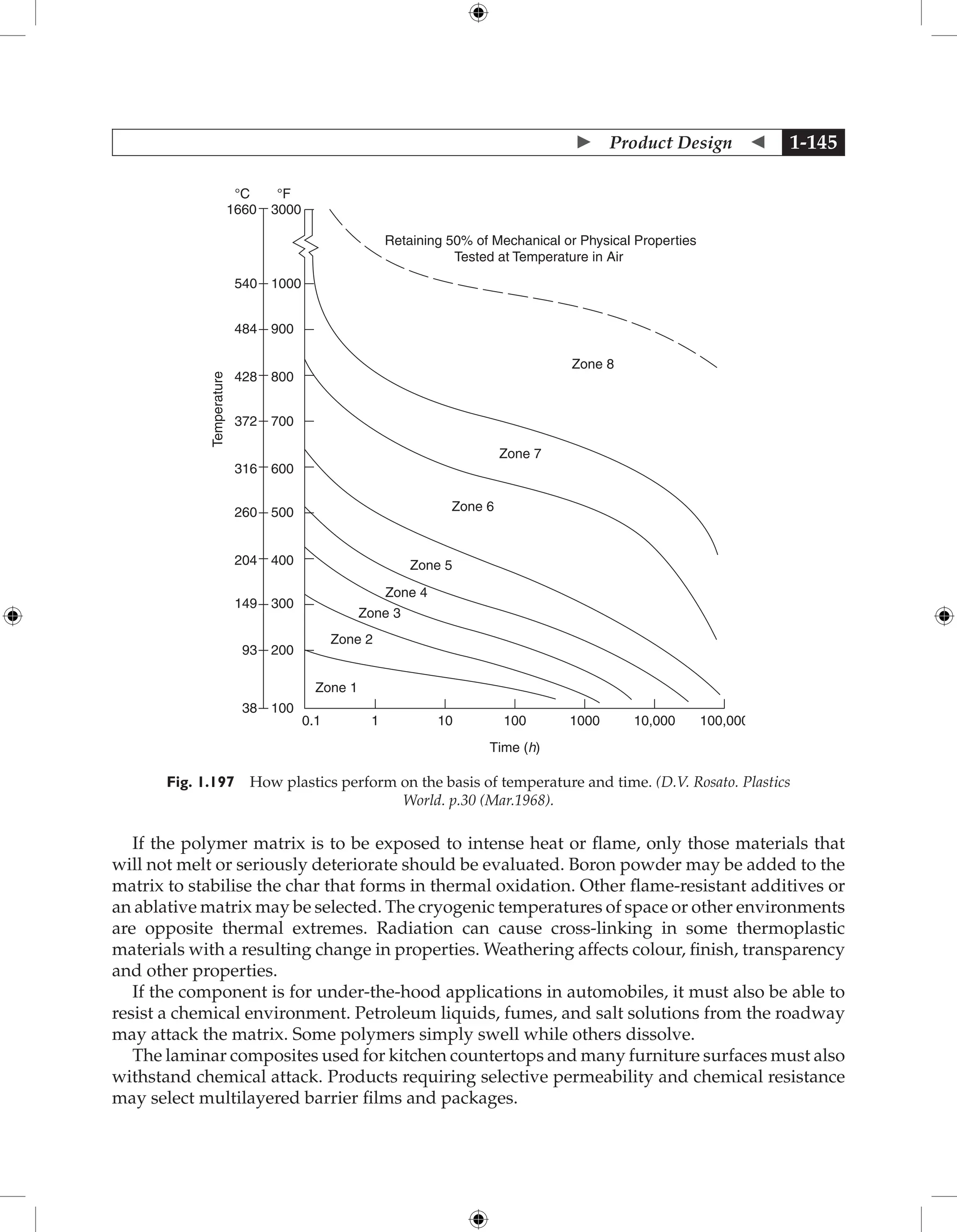

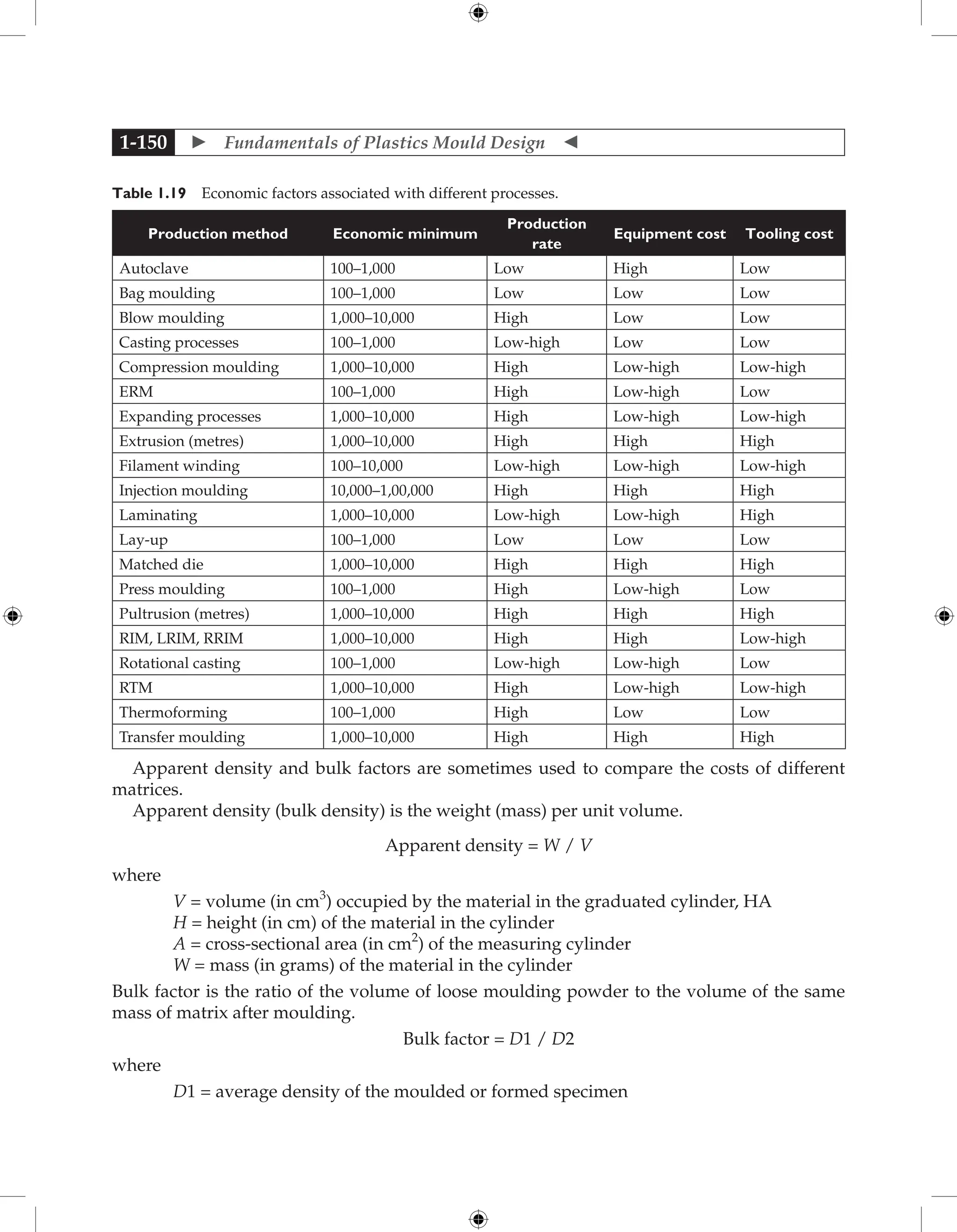

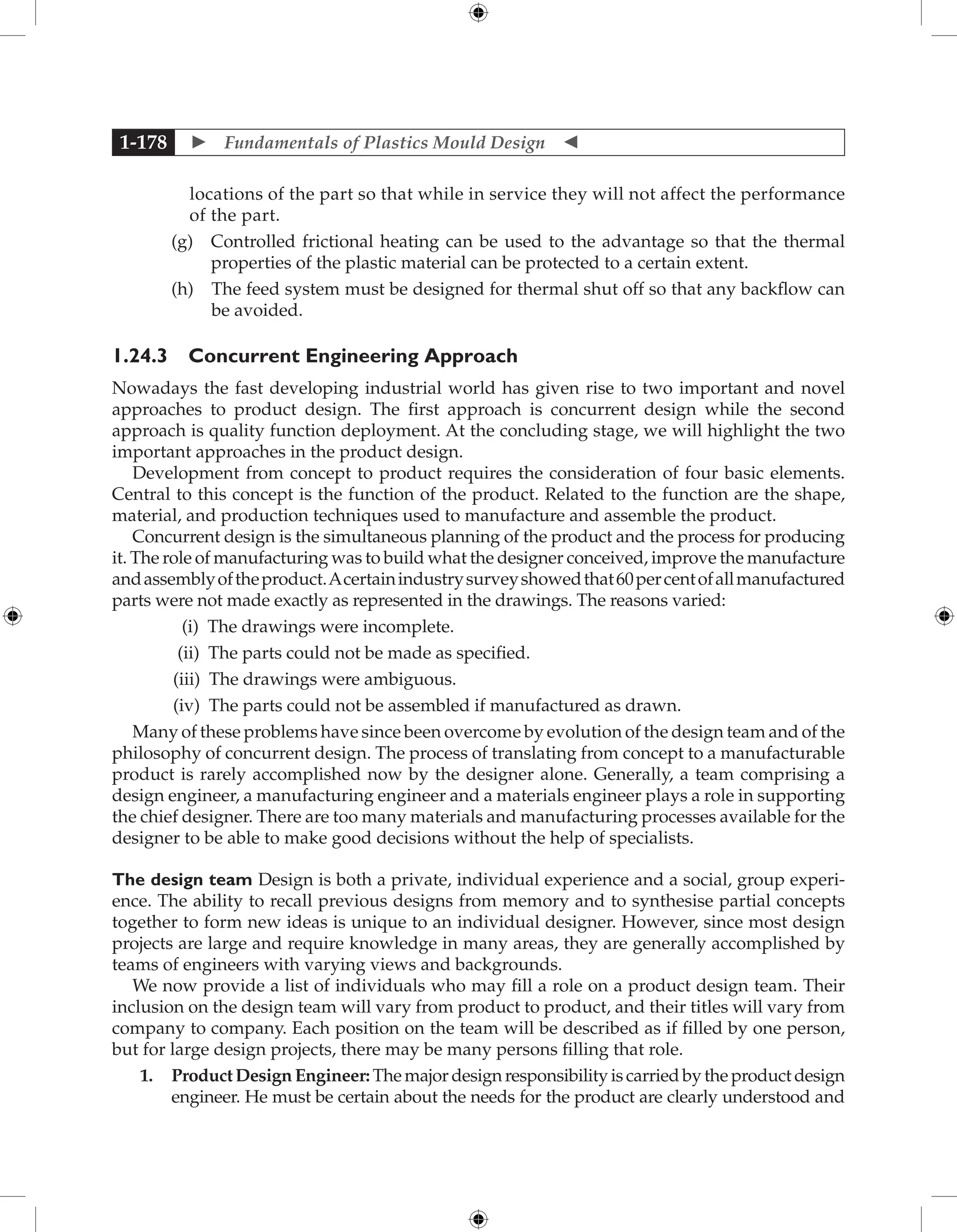

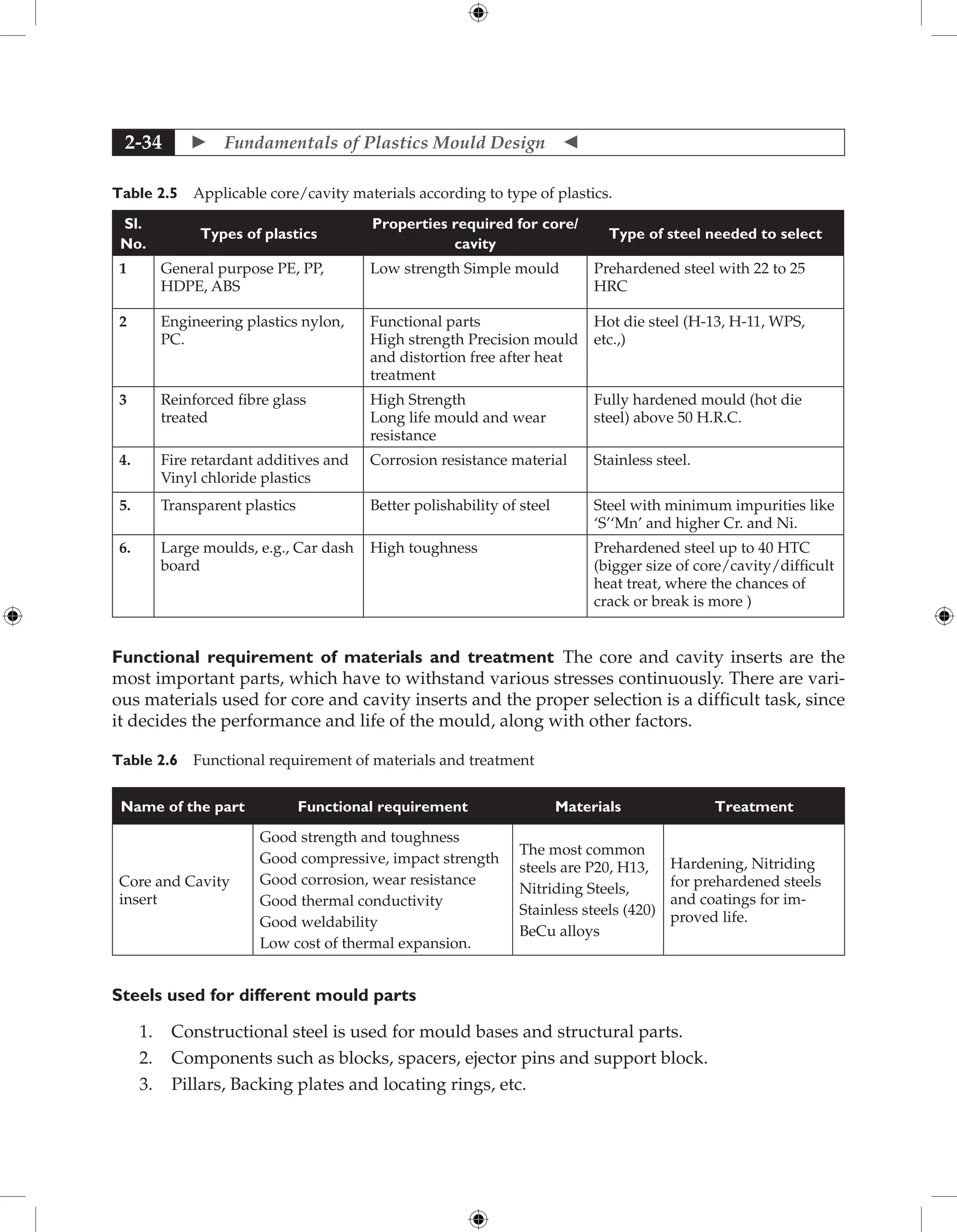

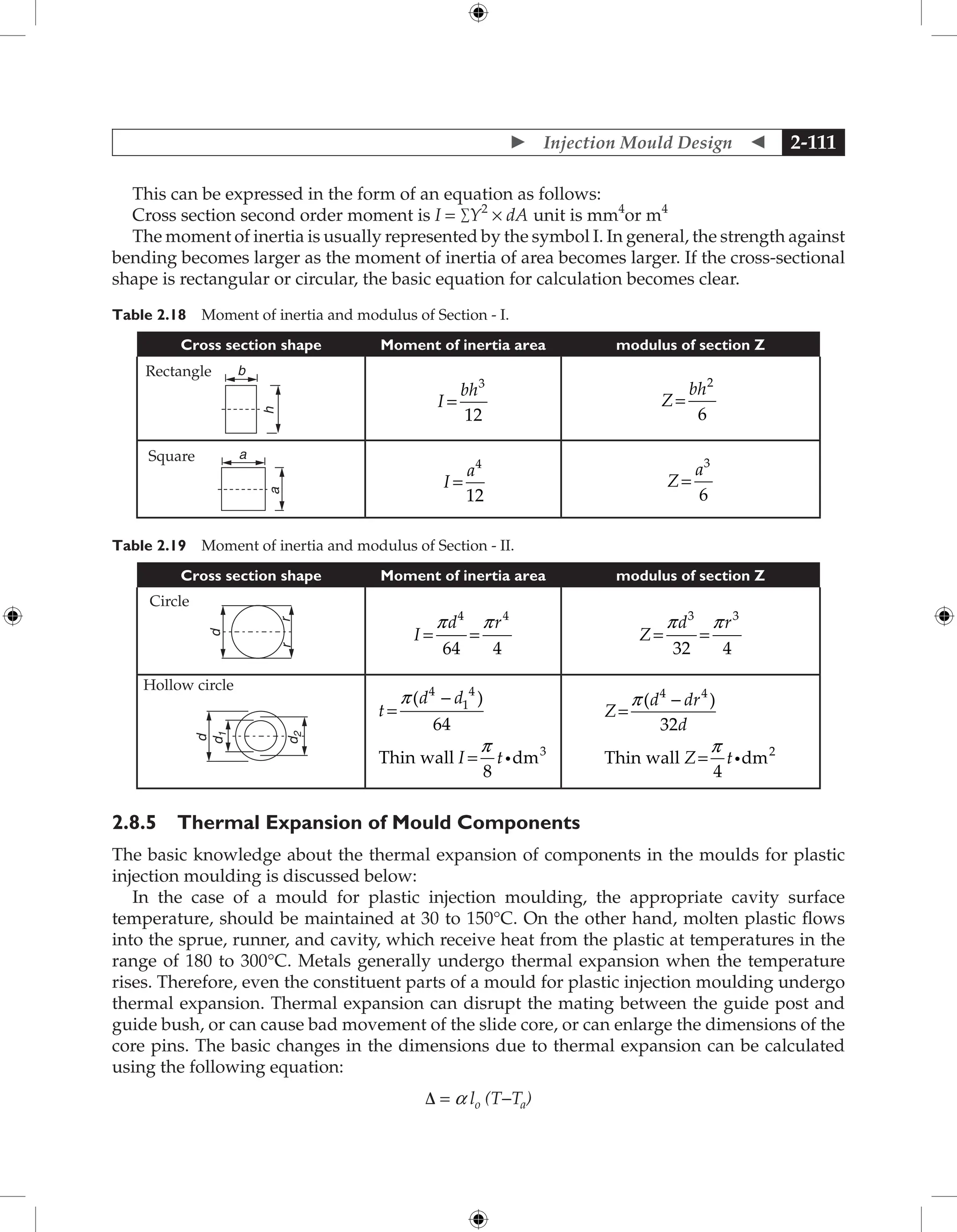

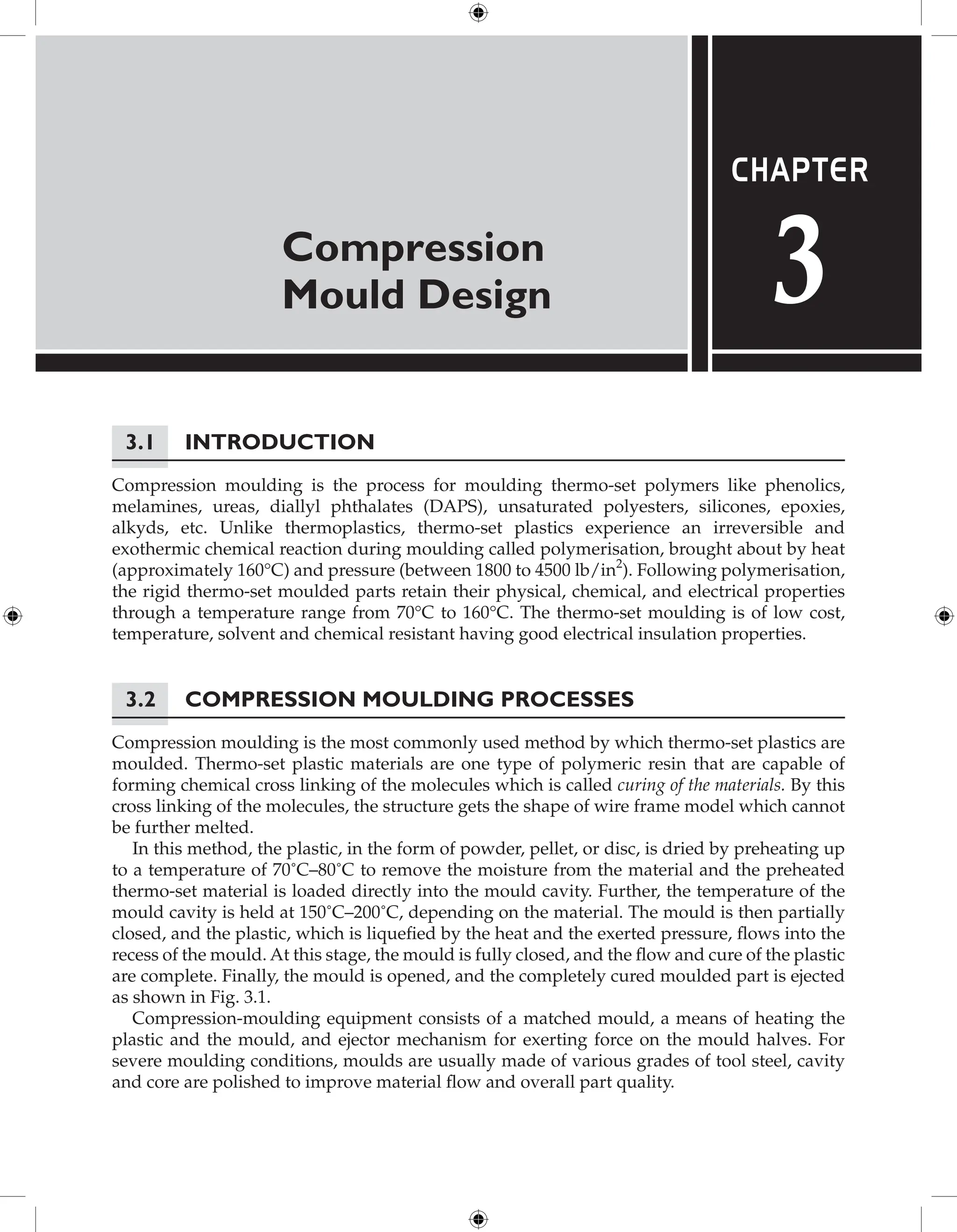

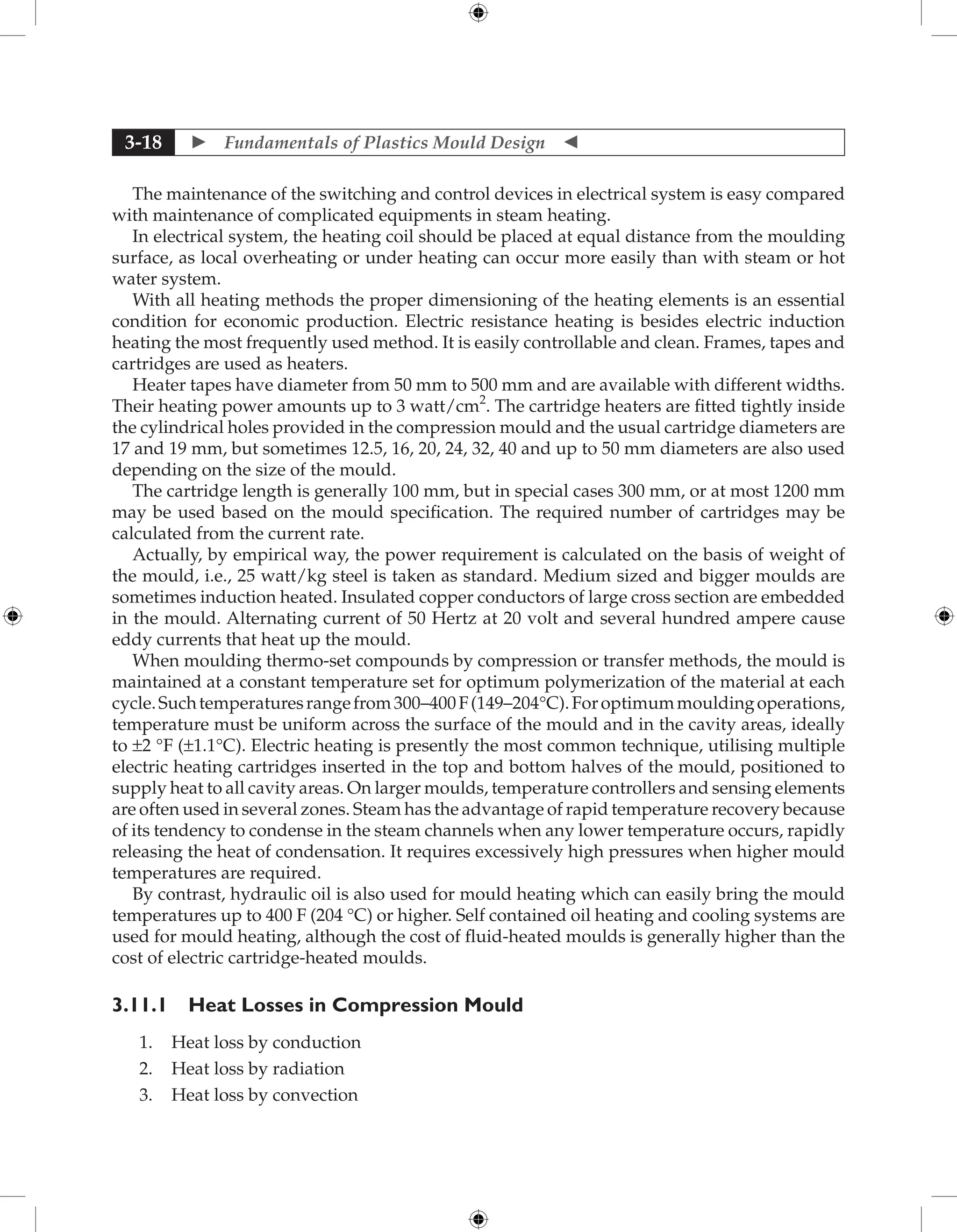

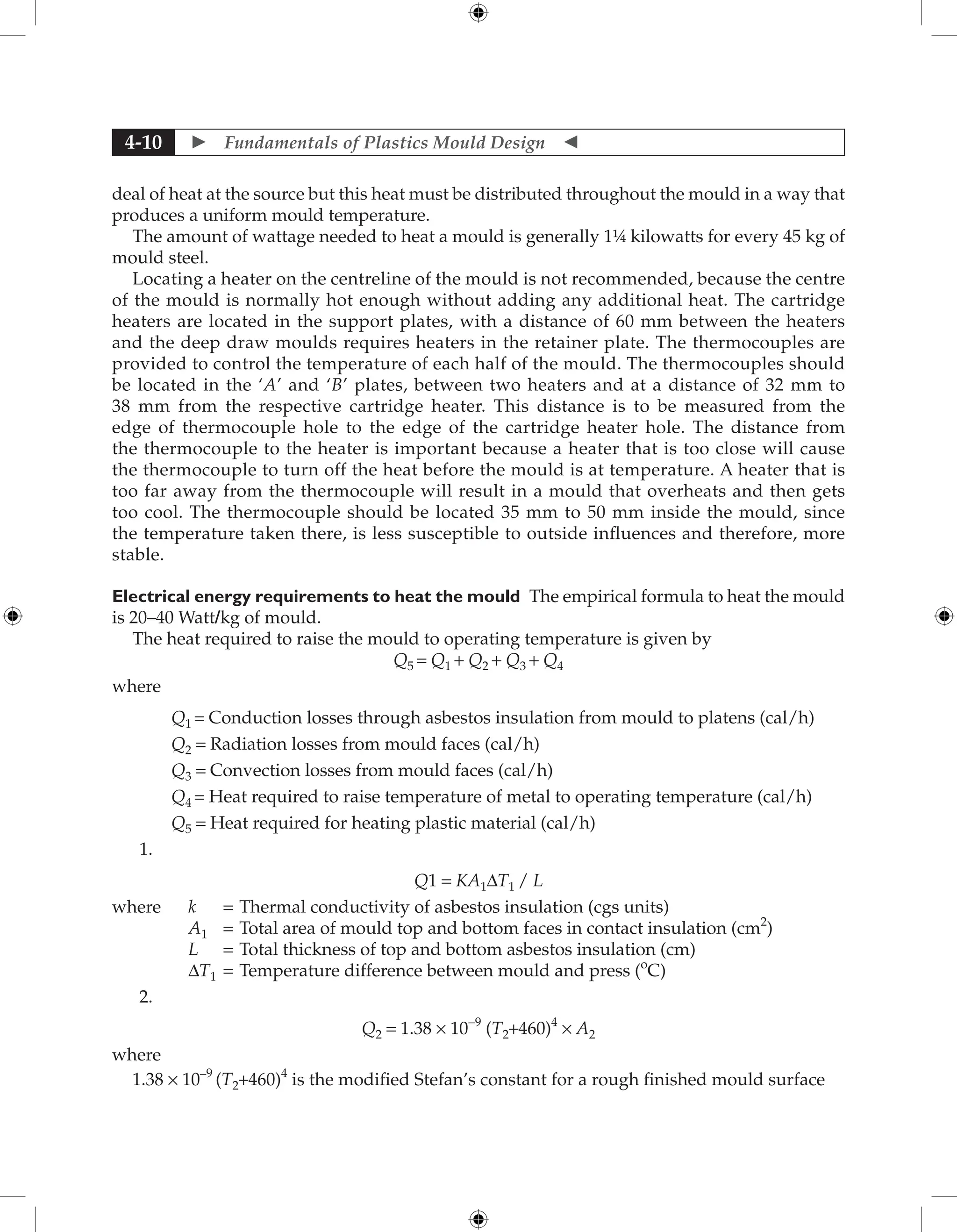

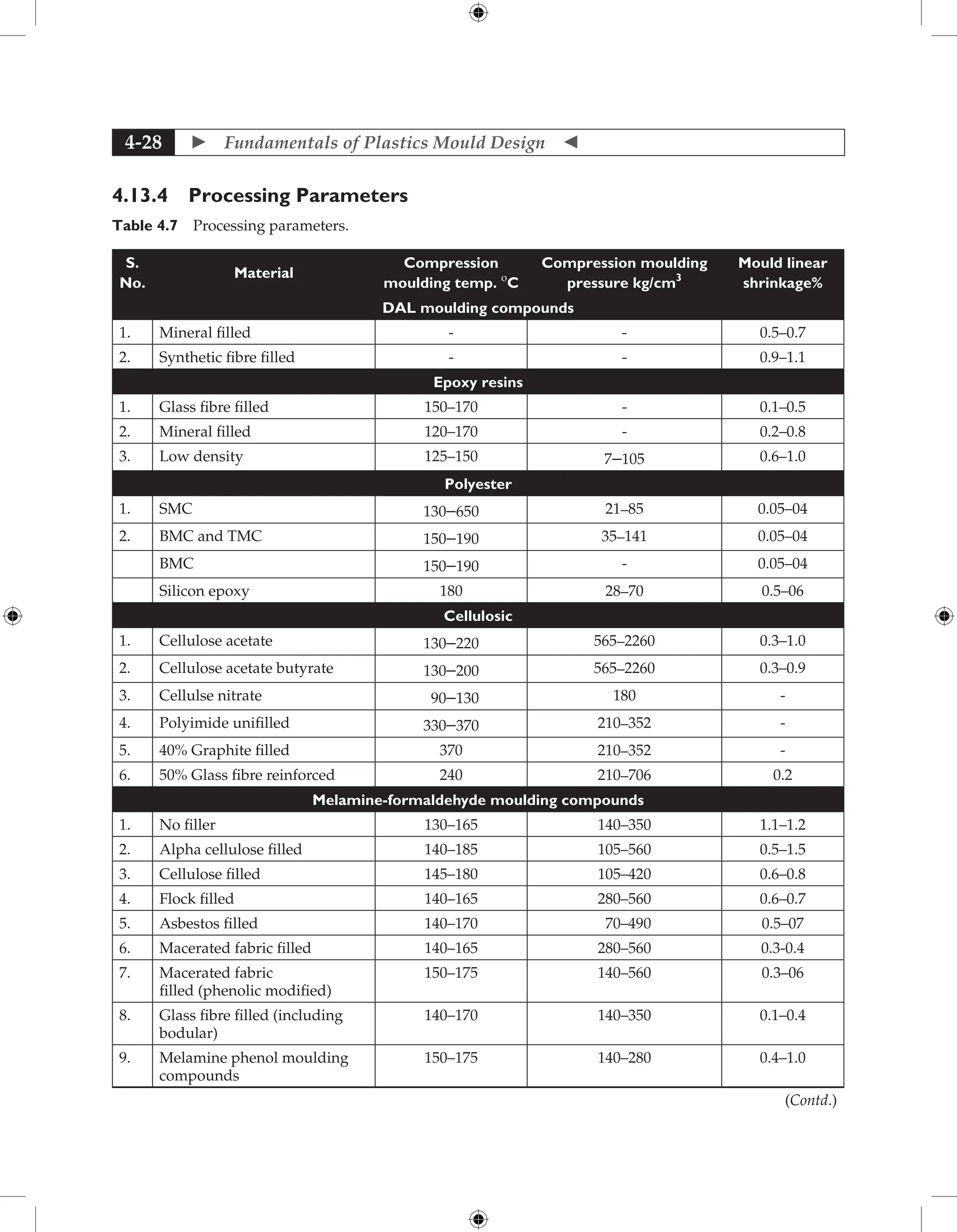

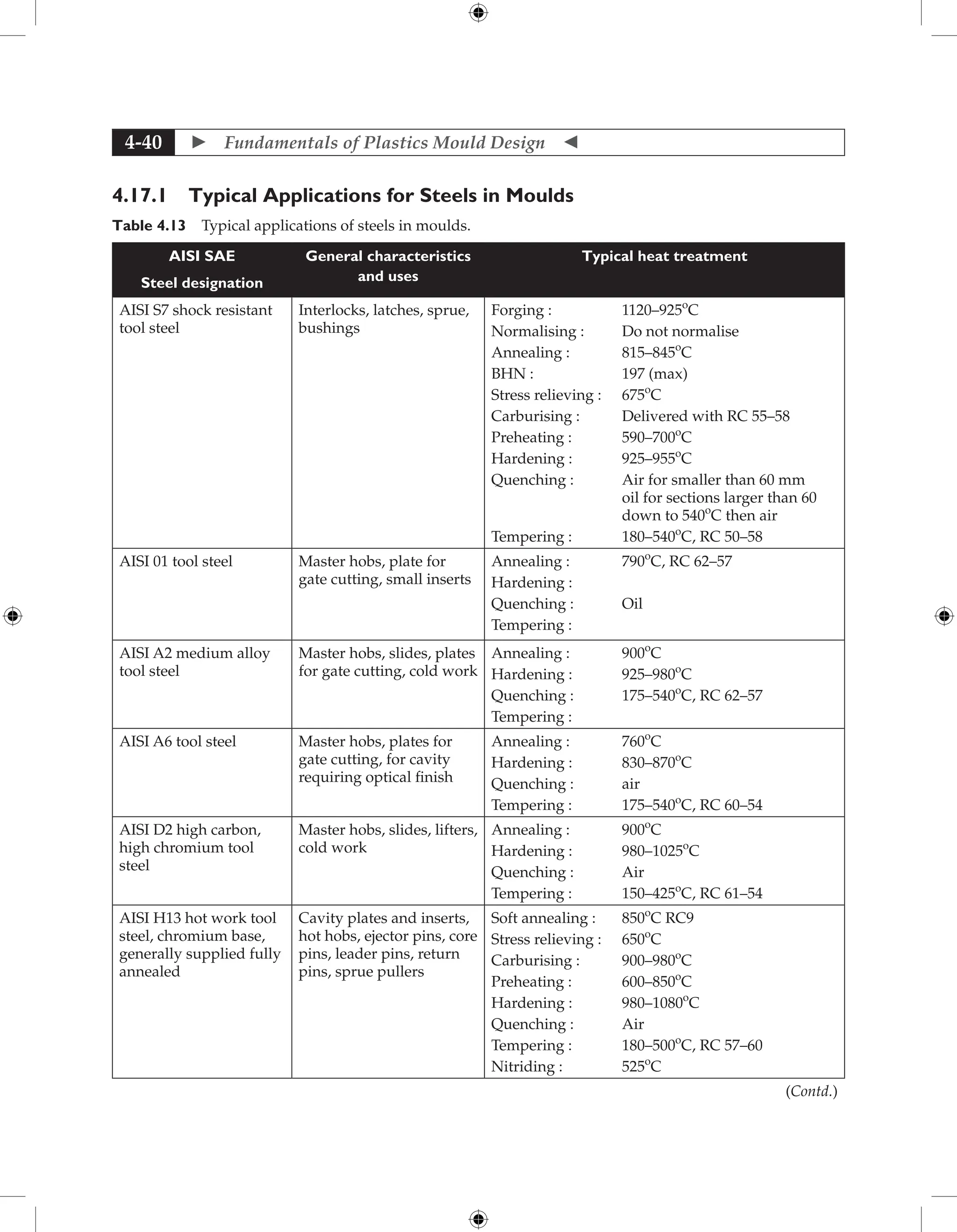

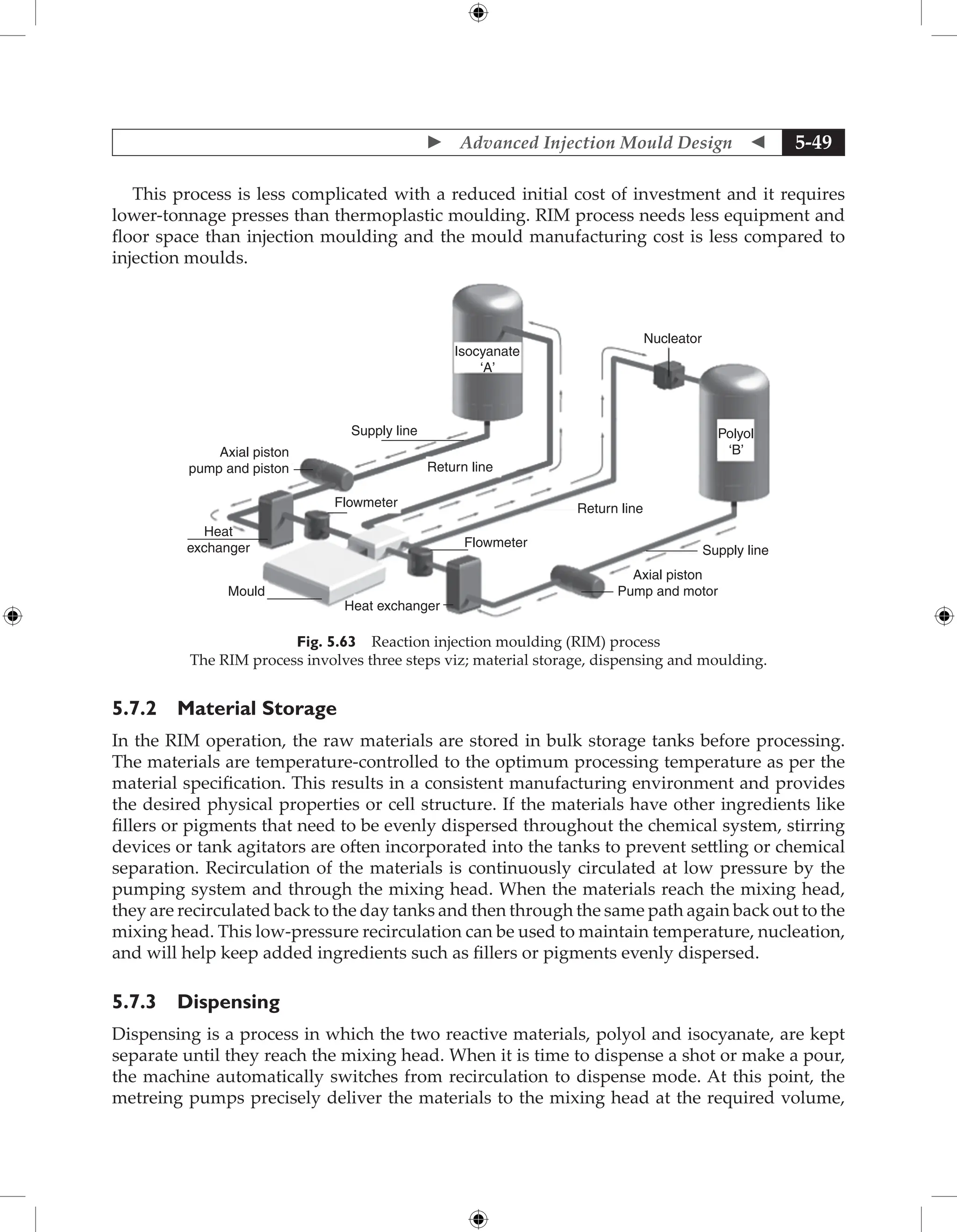

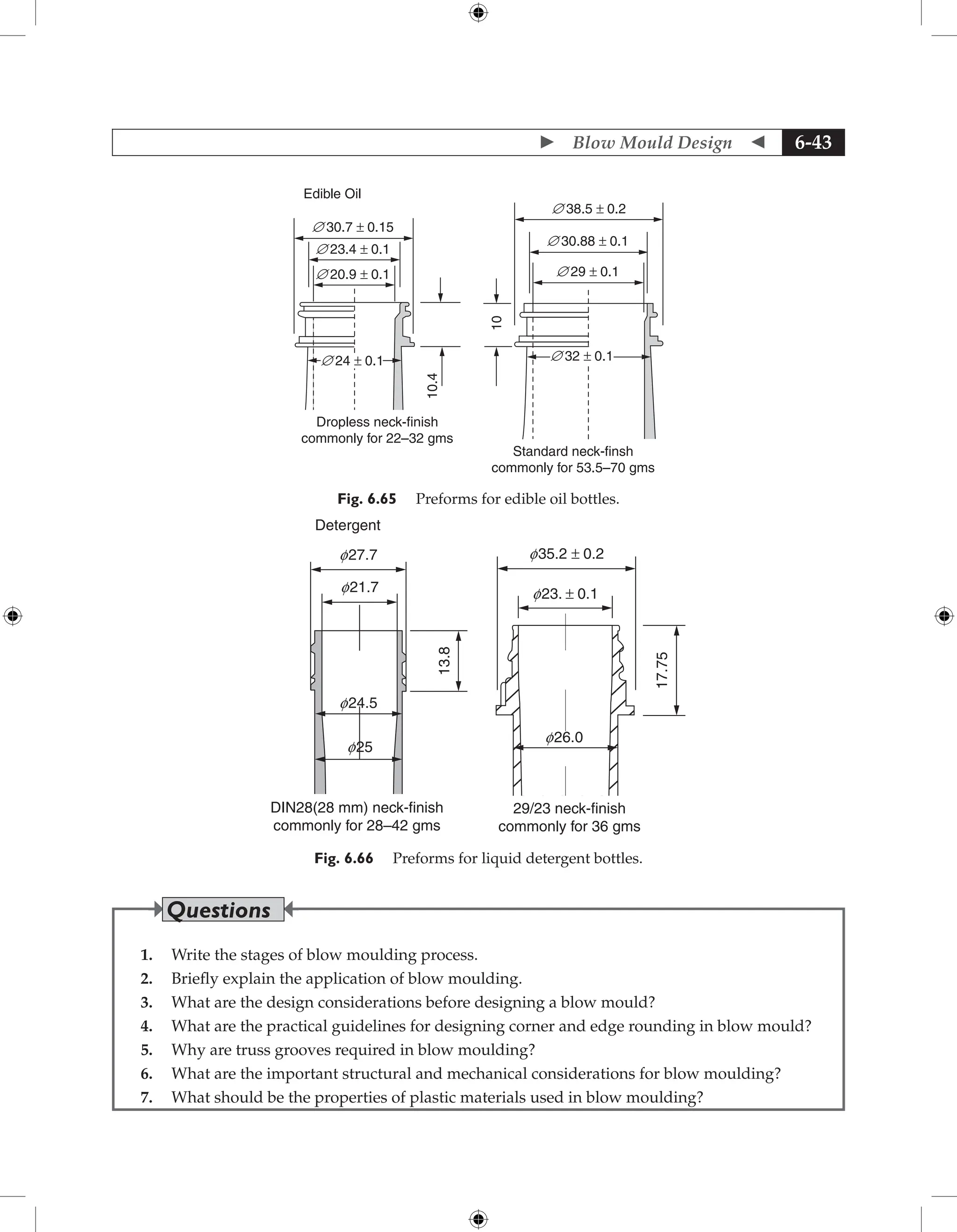

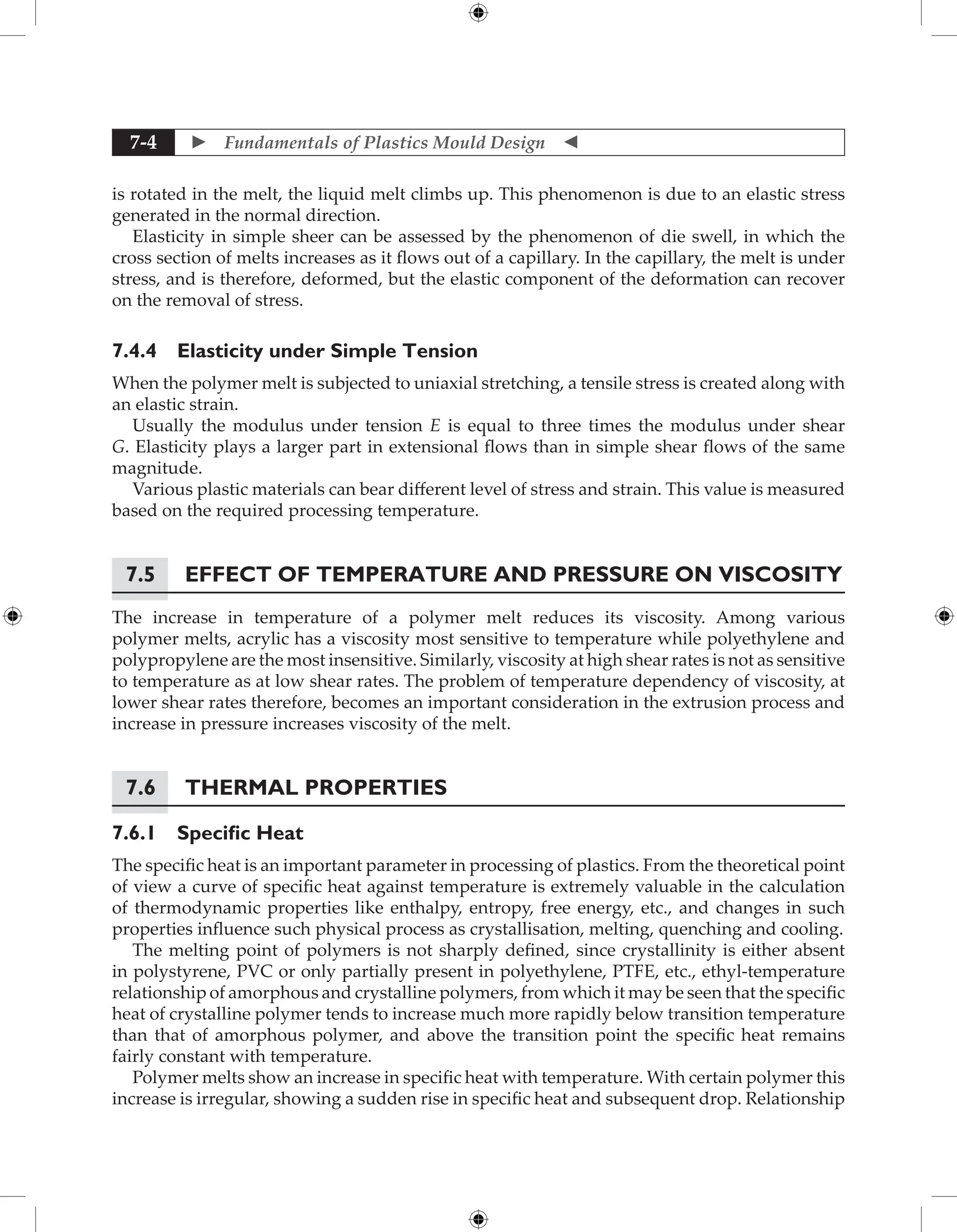

3. Plastic and metal gears generally fail because of wear or pitting associated with com-

pressive fatigue. The contact stress in this example will now be checked against the

allowable contact stress for Celcon. The allowable contact stress Sc for unlubricated

pairs is proportional to the reference value Sc in Fig.1.158 multiplied by the factor Ck,

which is given by

Ck = {0.70/[(1/E1 + 1/E2) cos f sin f ] } 0.5](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fundamentalsofmoulddesign-231217032858-869d3d7e/75/Fundamentals-of-Mould-Design-lecture-pdf-114-2048.jpg)

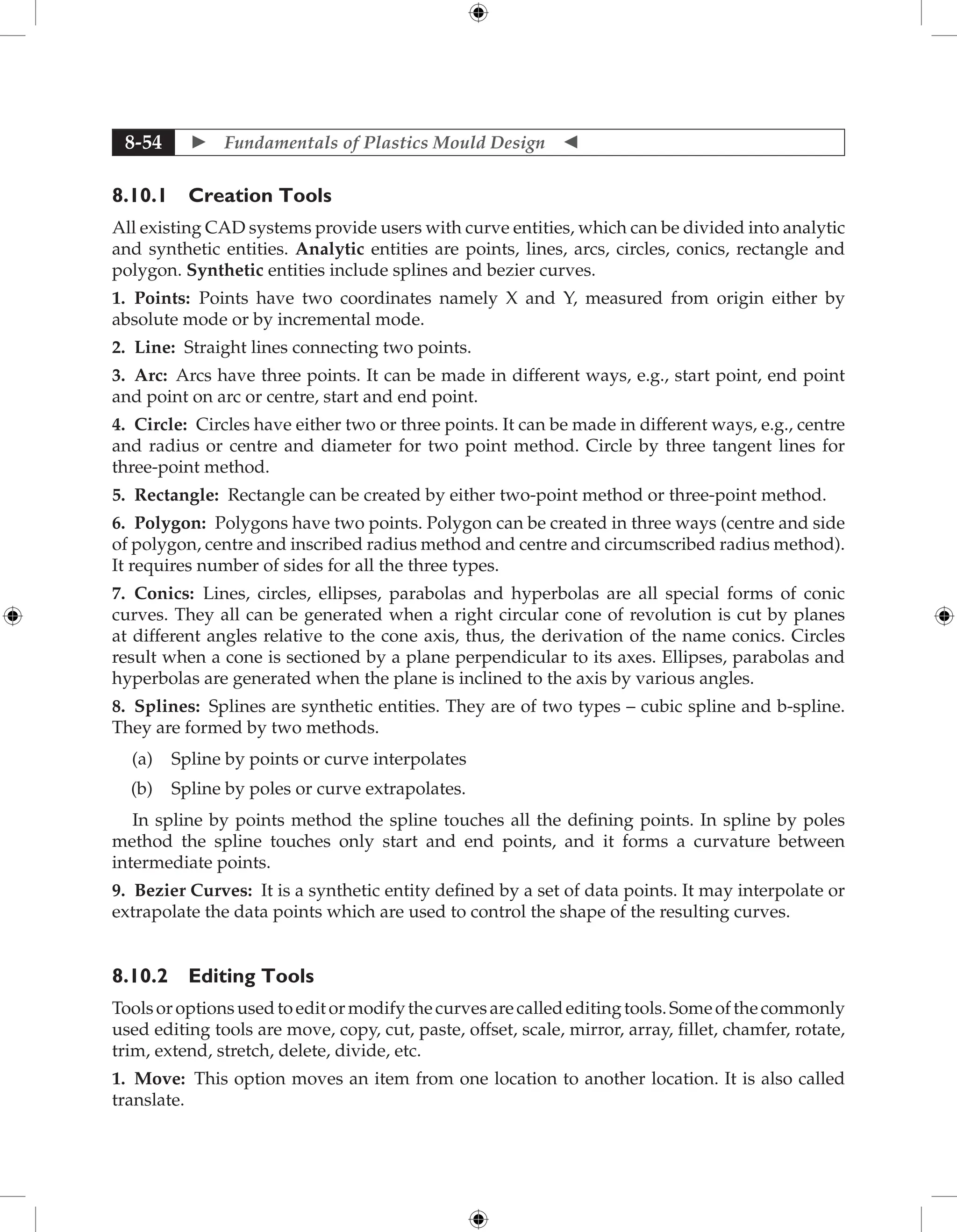

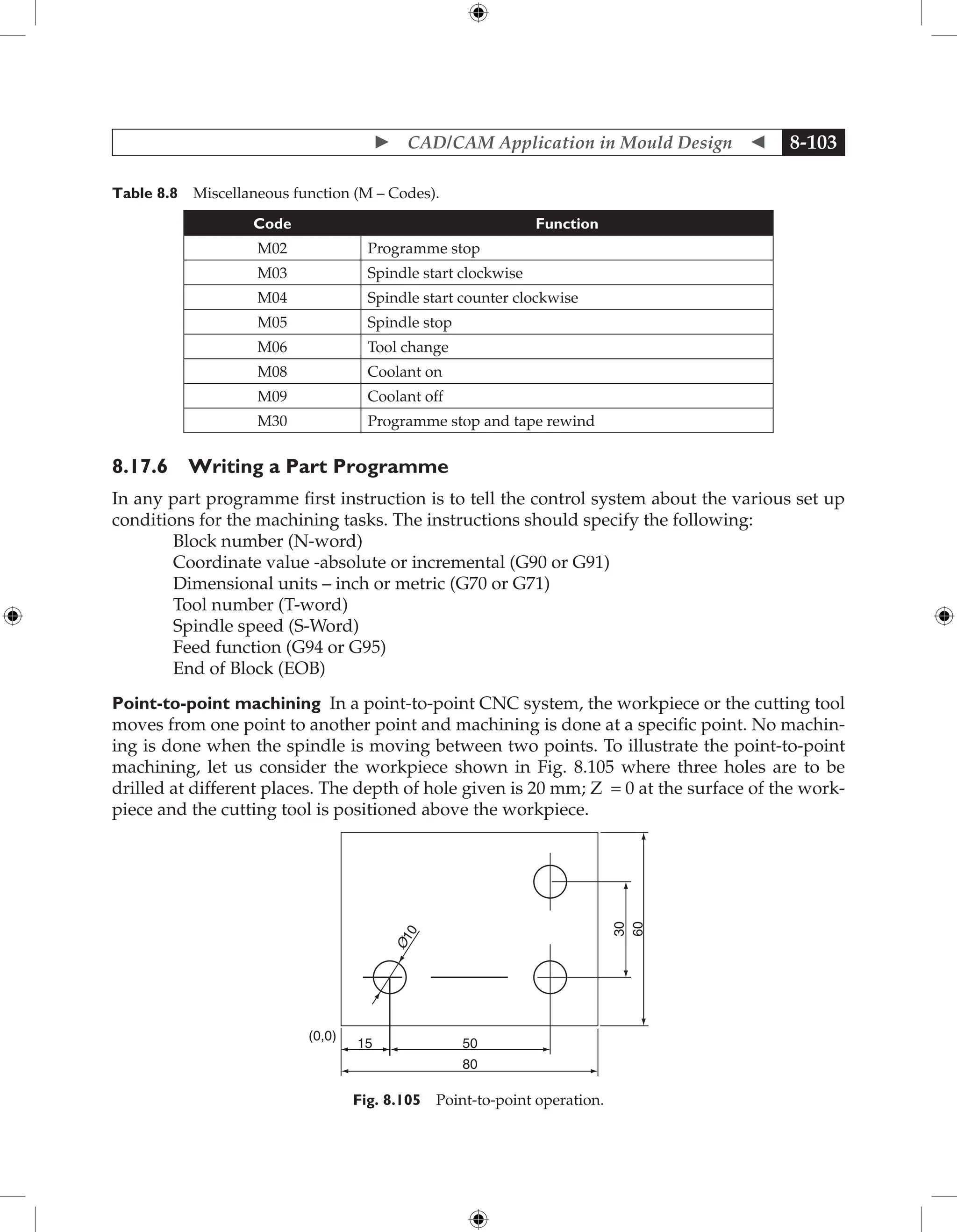

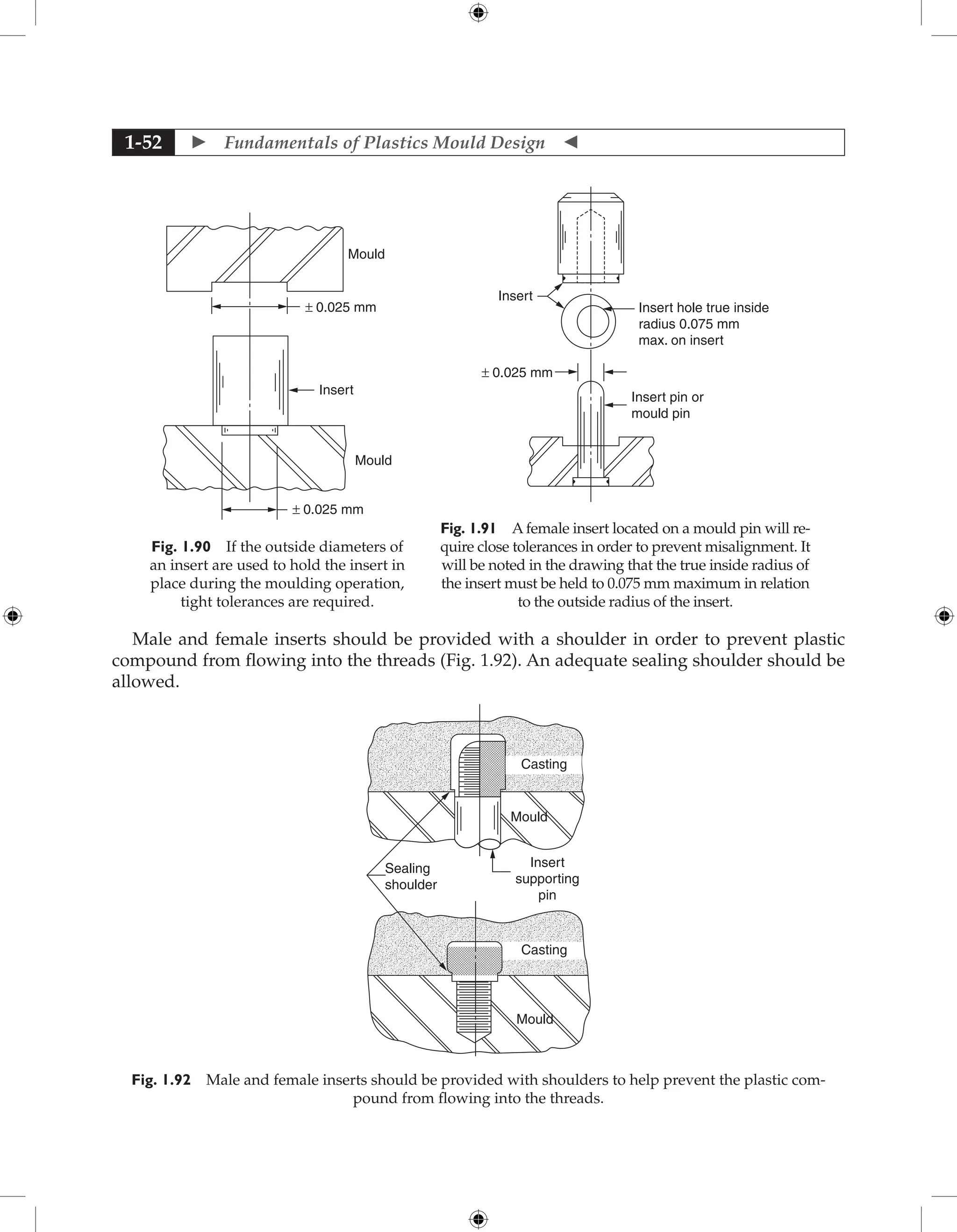

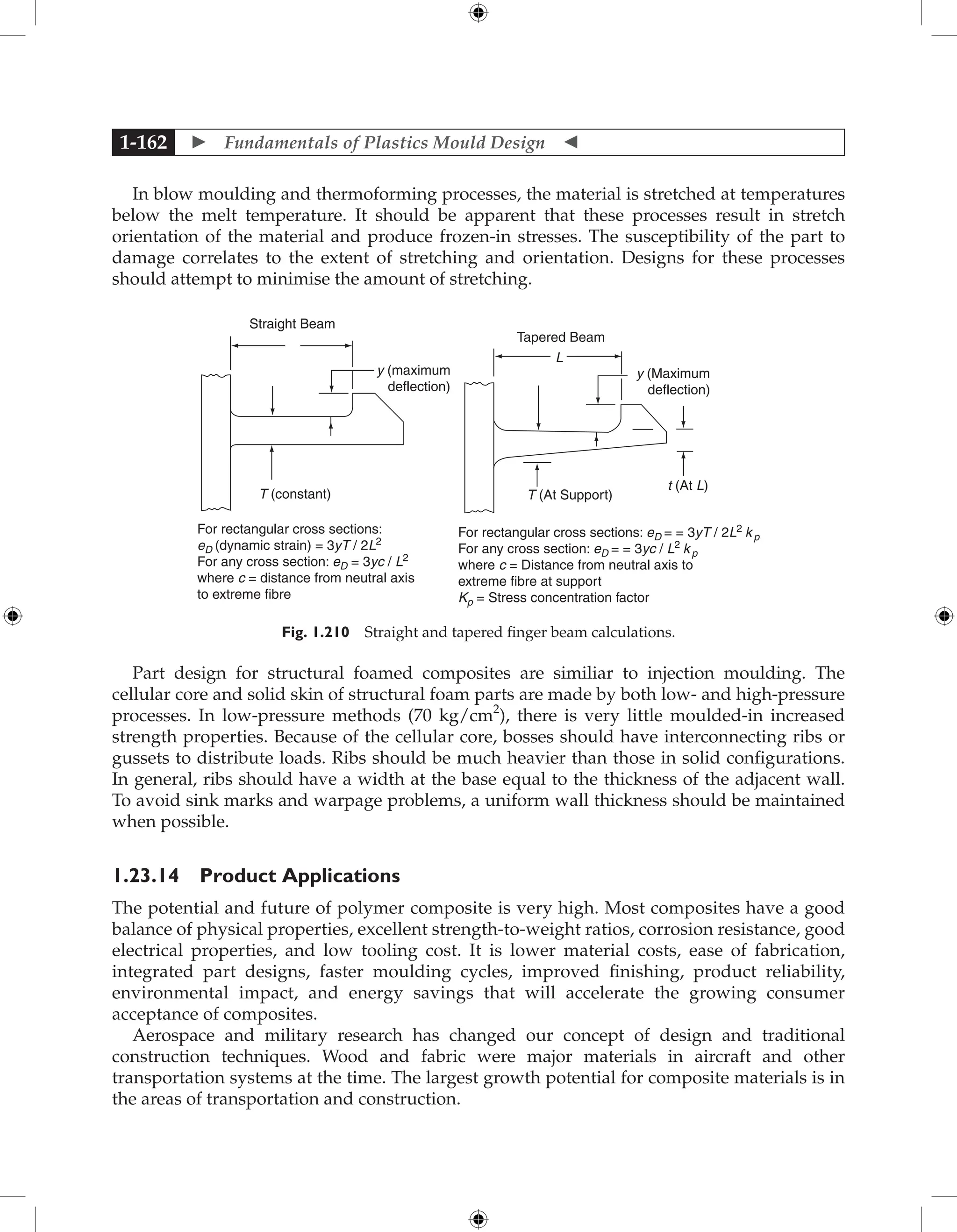

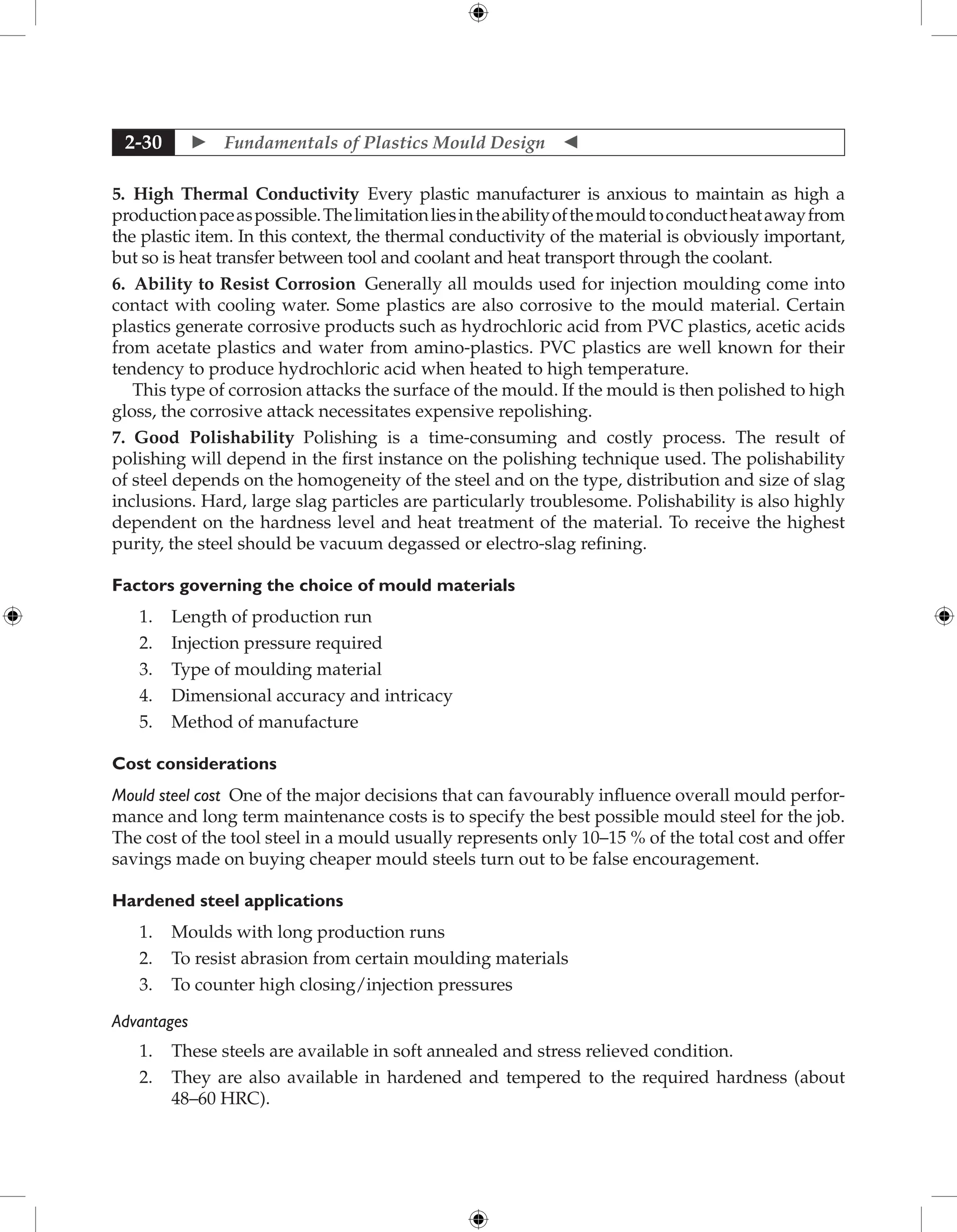

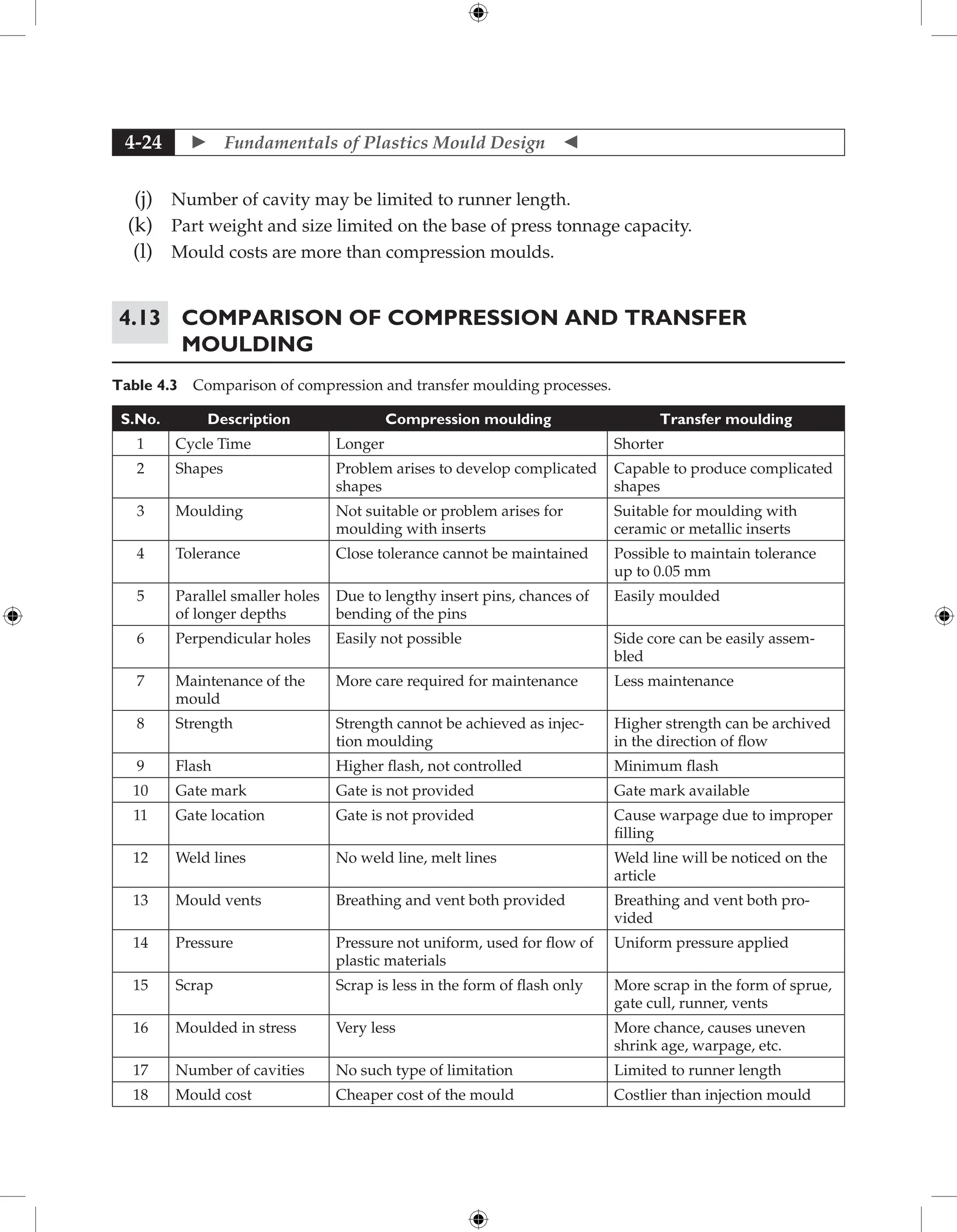

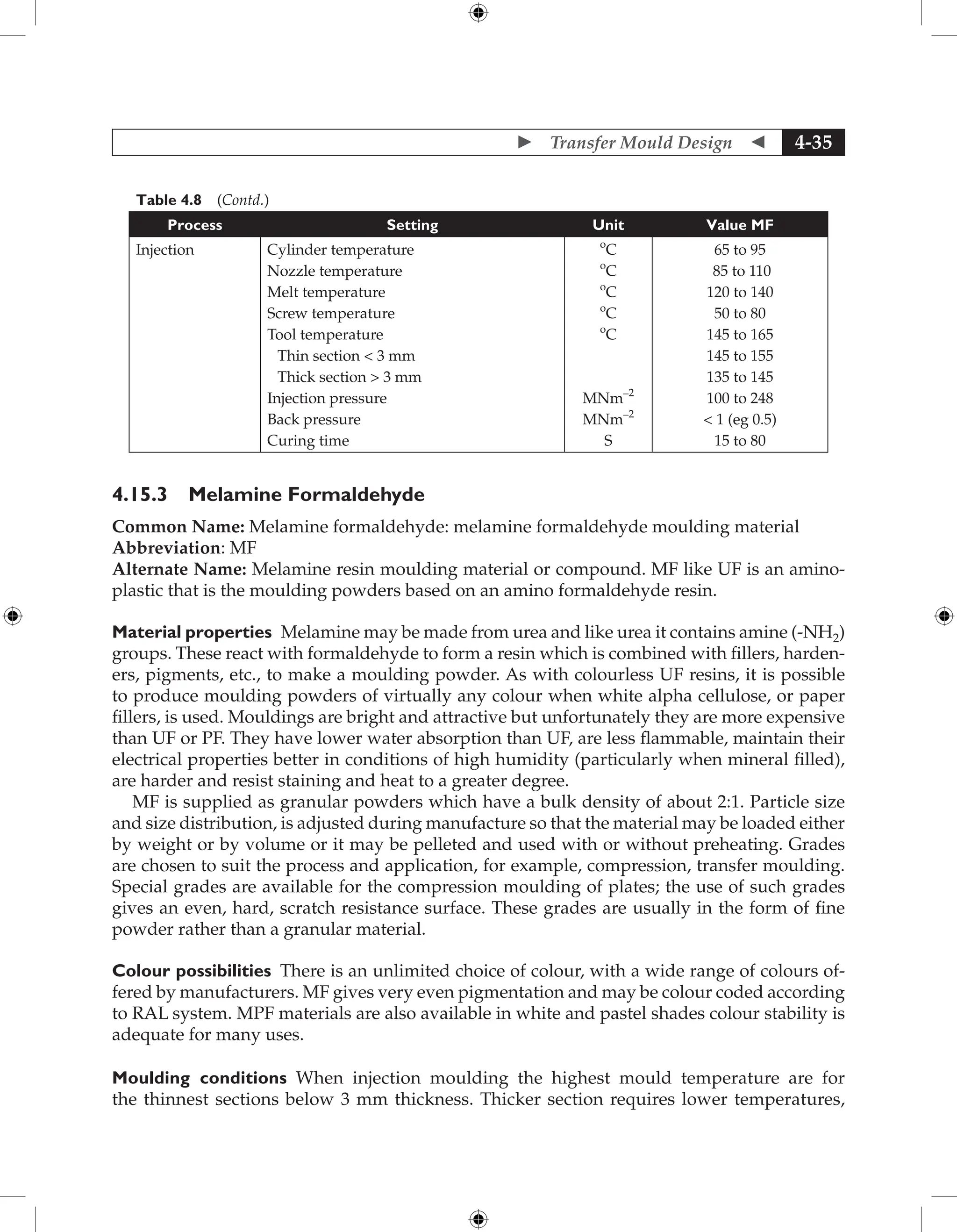

![ Fundamentals of Plastics Mould Design

1-102

E1 and E2 are Young’s moduli for the mating materials, and f is the pressure angle.

E1=29×106 psi for the steel pinion. E2=315,000 psi for the Celcon gear from Table 1.11 at

100F. Equation 2.3 gives Ck = 824. Figure 1.158 gives Sc - 2800 at 107 cycles. Therefore,

the allowable contact stress is

Sac = Sc Ck/639 = 2800 × 824/639 = 3610 psi

The applied contact stress is given by

sc = {[Lt Ck (m + 1)]/Dp m}0.5 = 9550 psi

Since the applied sc is considerably larger than the allowable sc, this design is not feasible.

The simplest fix is to increase gear face width from 0.300 to at least 2.10 in. The problem

then is that the pinion face width is about four times its pitch diameter, which will require

careful shaft alignment. A better solution might be to use a Celcon–Celcon pair. The advantage

is the much greater accommodation of plastic-plastic gear pairs to tooth misalignment, which

allows design of gears with higher face width/pitch diameter ratios.

Table 1.9 Tensile yield strength versus temperature for Celcon acetal copolymer*.

Temperature o

C –18 10 38 66 93 100

Yield strength (MPa) 83 67 50 38 29 28

* Celcon M90, unfilled virgin resin (Hoechst Celanese Corp.).

Table 1.10 Lewis form factor Y for 20o

pressure angle, full depth gear teeth.

Number

of teeth

12 14 16 18 20 24 30 38 50 75 100 300

Y 0.415 0.468 0.500 0.520 0.544 0.571 0.605 0.650 0.696 0.734 0.758 0.802

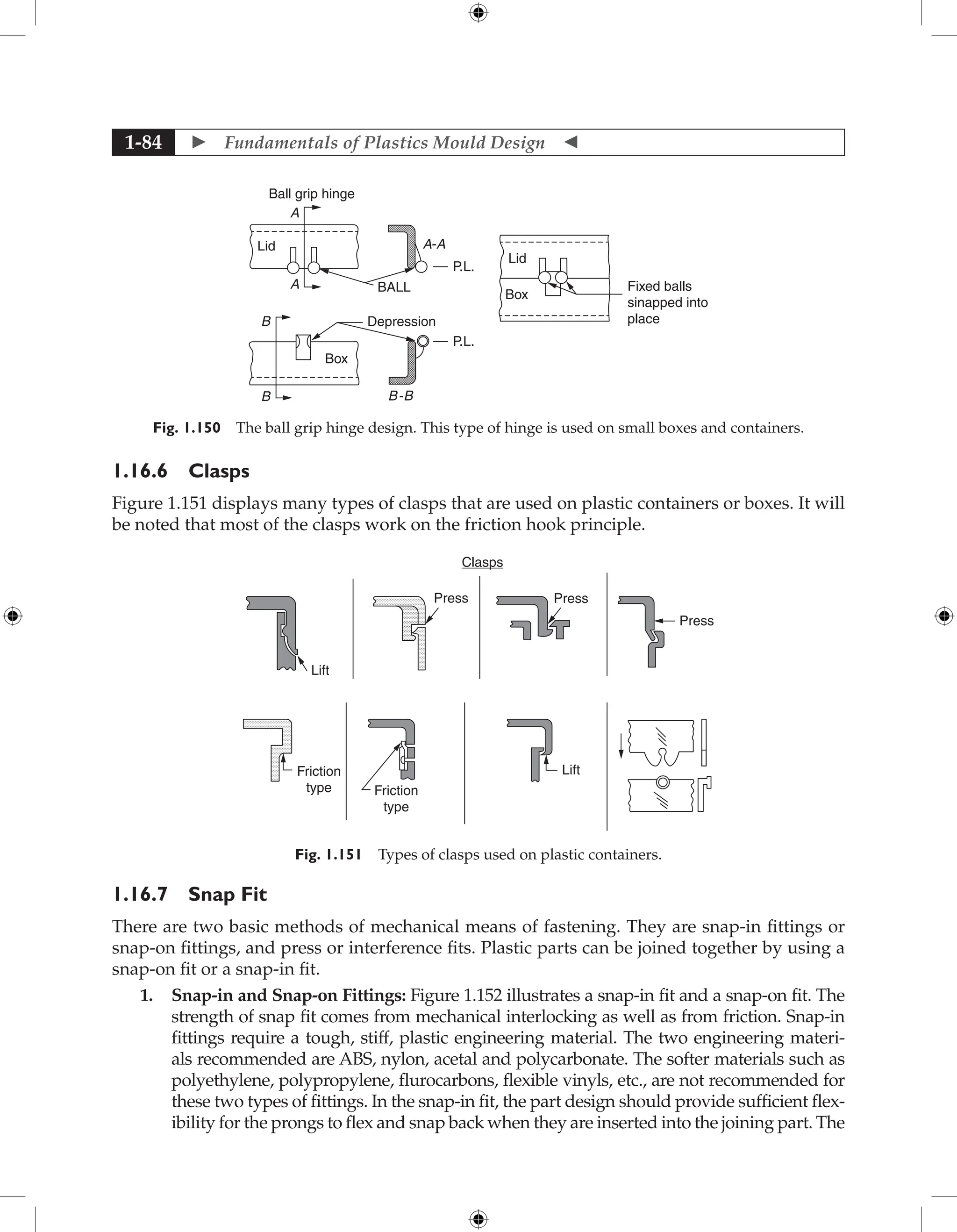

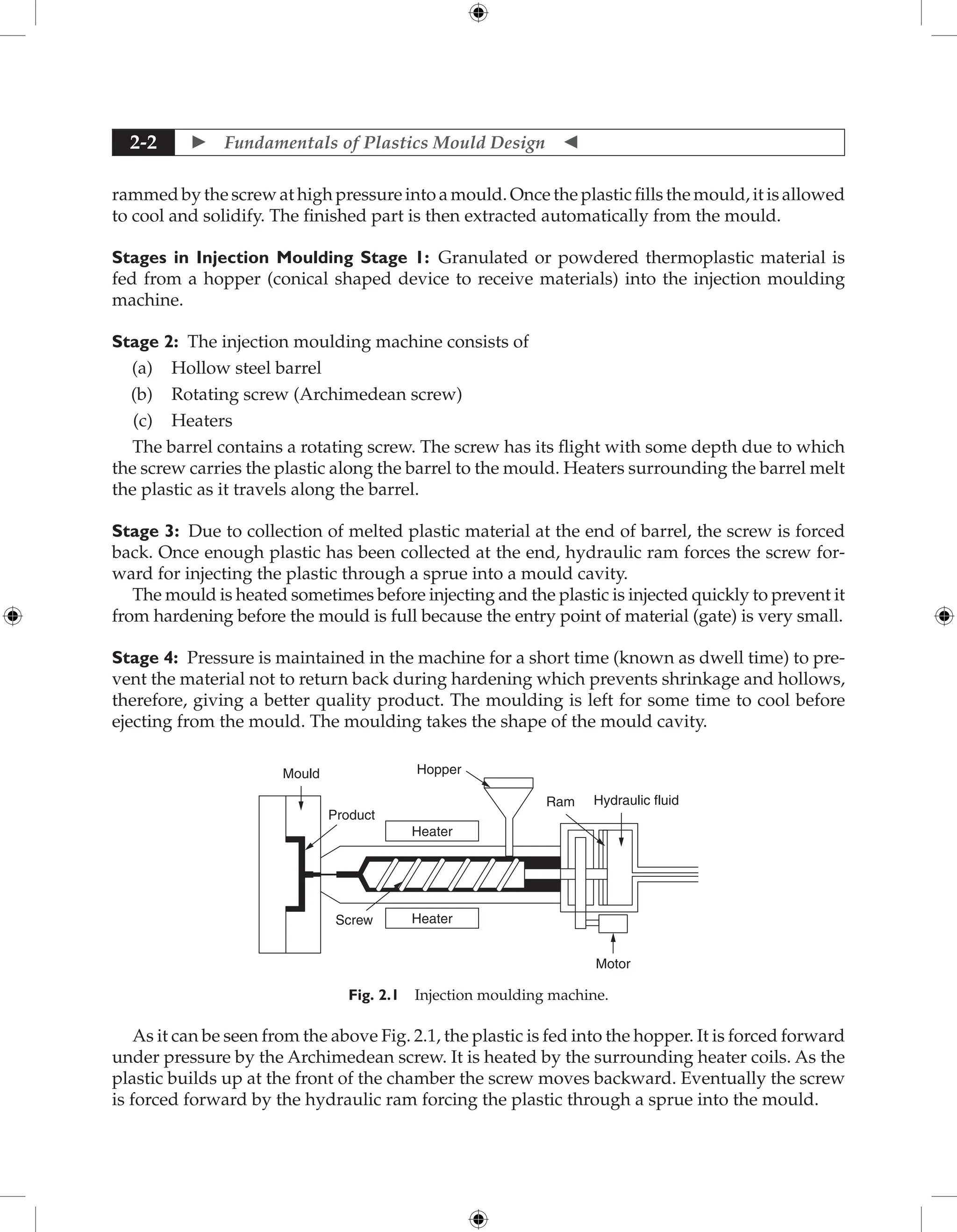

73°F (23°C)

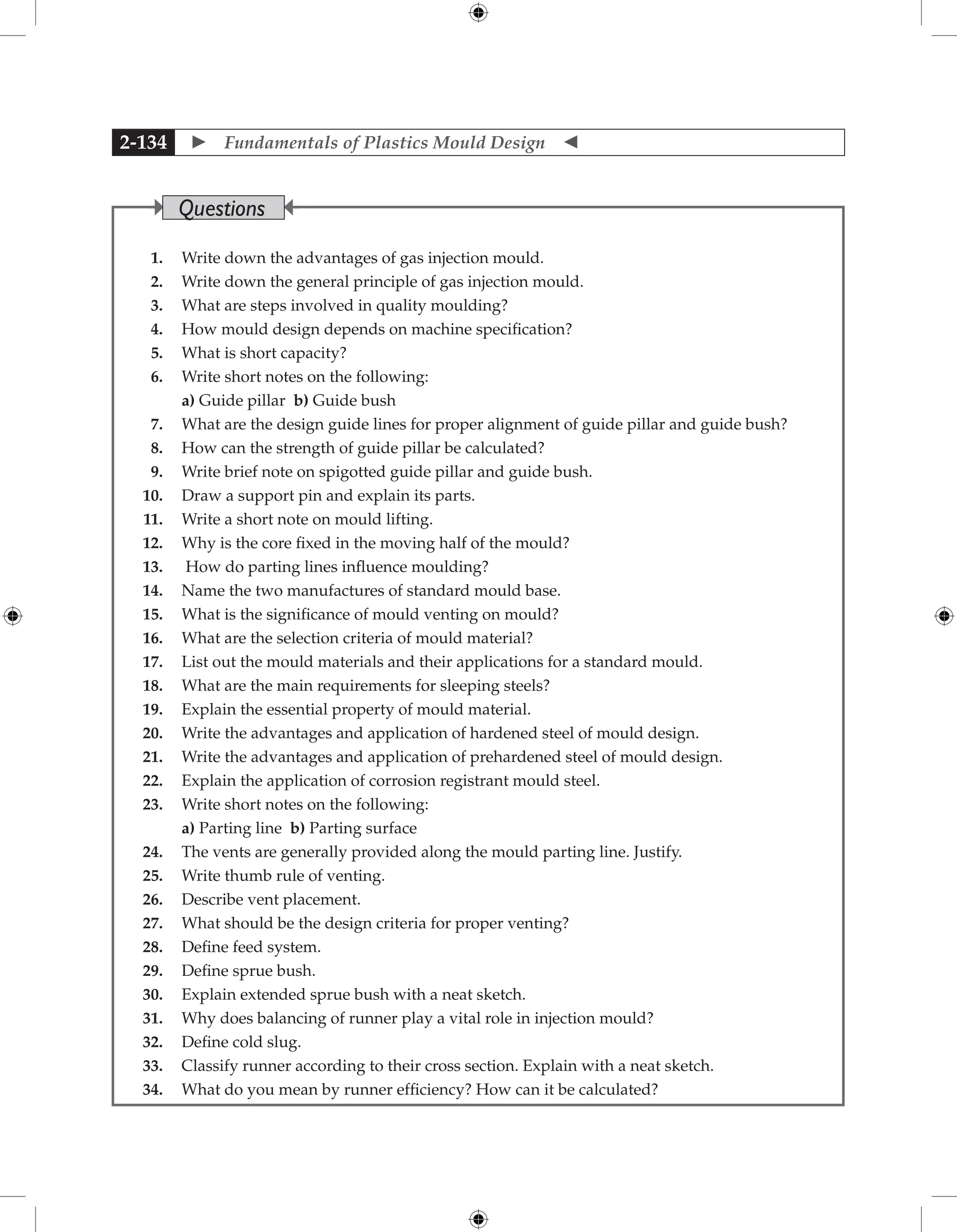

20° Pressure Angle

Celcon Gear and Pinion

Unlubricated

Pitch Line Velocity = 2330 FPM (710m/min.)

Curve reduced 25% form Experimental

Data (becuase data taken under laboratory

conditions)

104

2000

(140)

3000

(210)

4000

(280)

5000

(350)

6000

(420)

7000

(490)

105

106

NUMBER OF REVOLUTINS TO GEAR FAILURE

MAXIMUM

ALLOWABLE

CONTACT

STRESS

Sc,

psi

(KG/cm

2

)

107

108

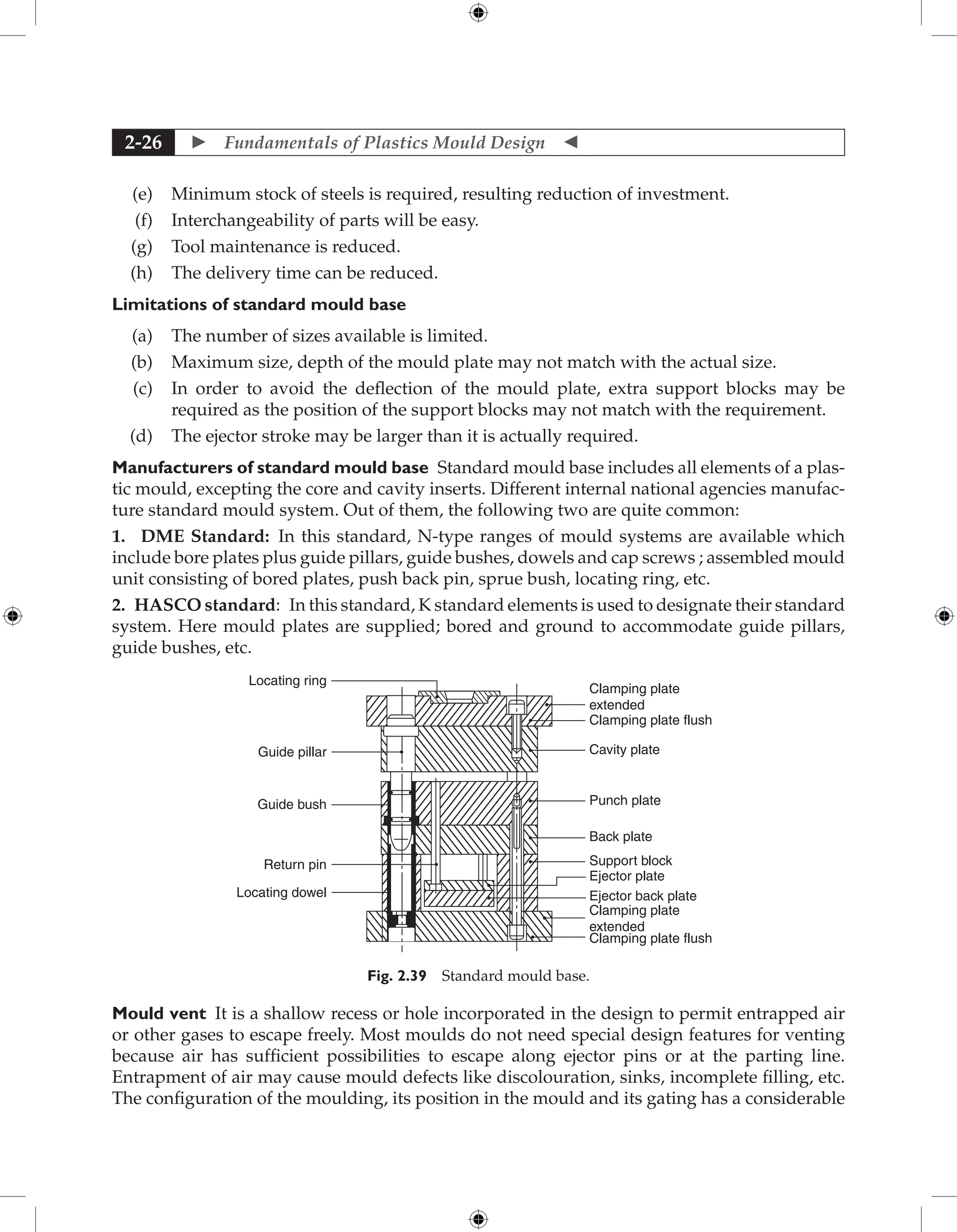

Fig. 1.158 Allowable surface contact stress versus number of gear revolutions to failure by surface wear

for unfilled Celcon (Hoechst Celanese Corp.).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fundamentalsofmoulddesign-231217032858-869d3d7e/75/Fundamentals-of-Mould-Design-lecture-pdf-115-2048.jpg)

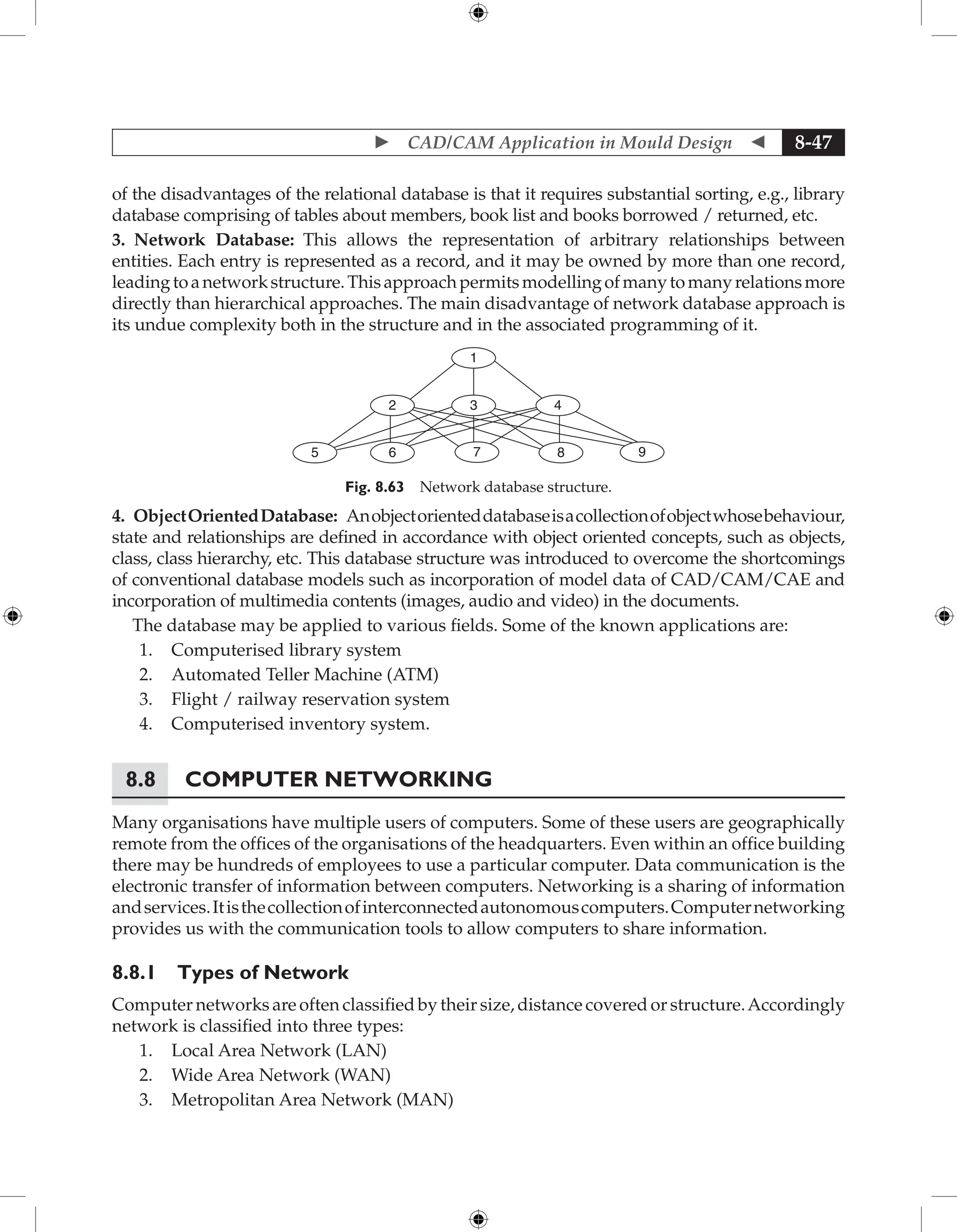

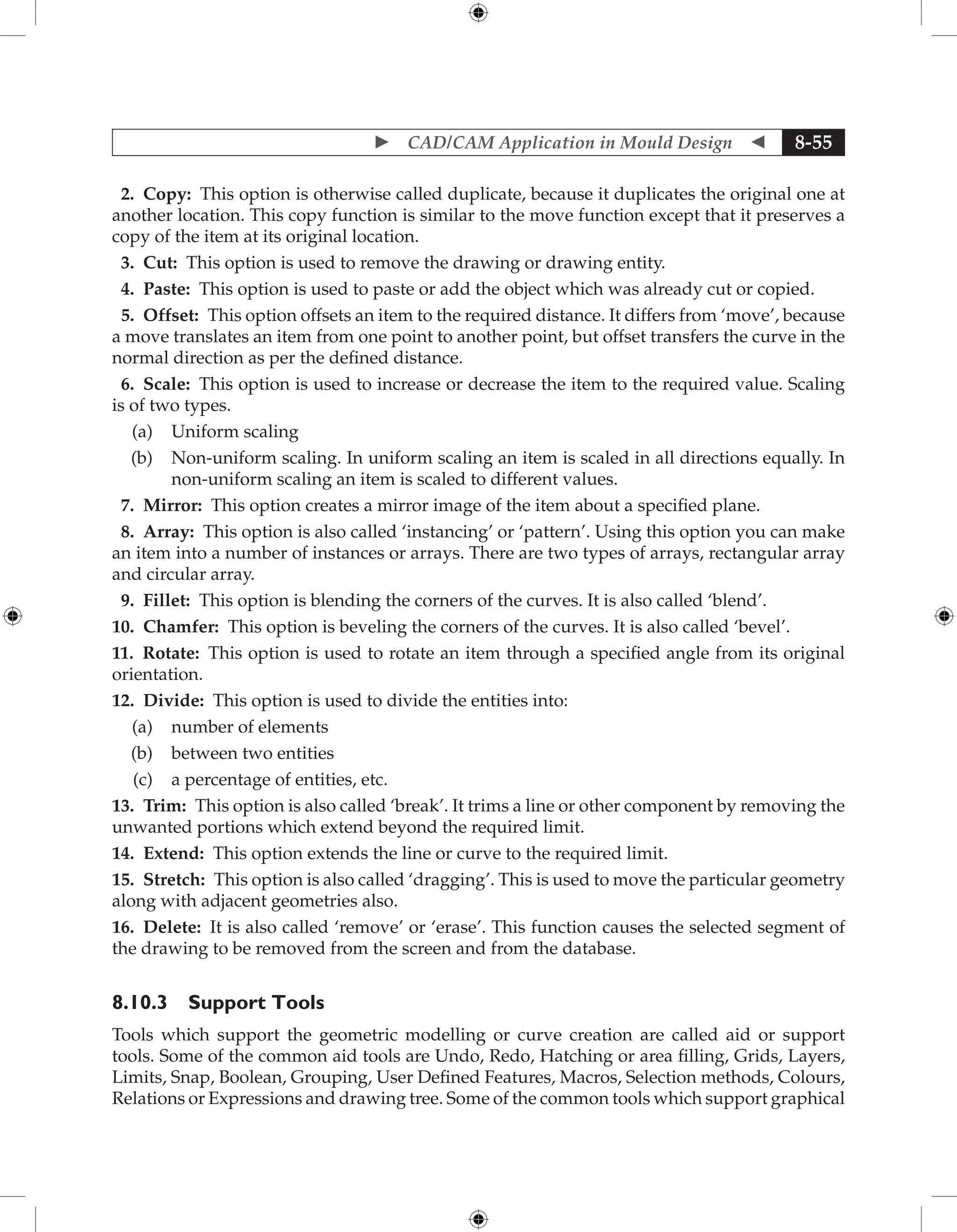

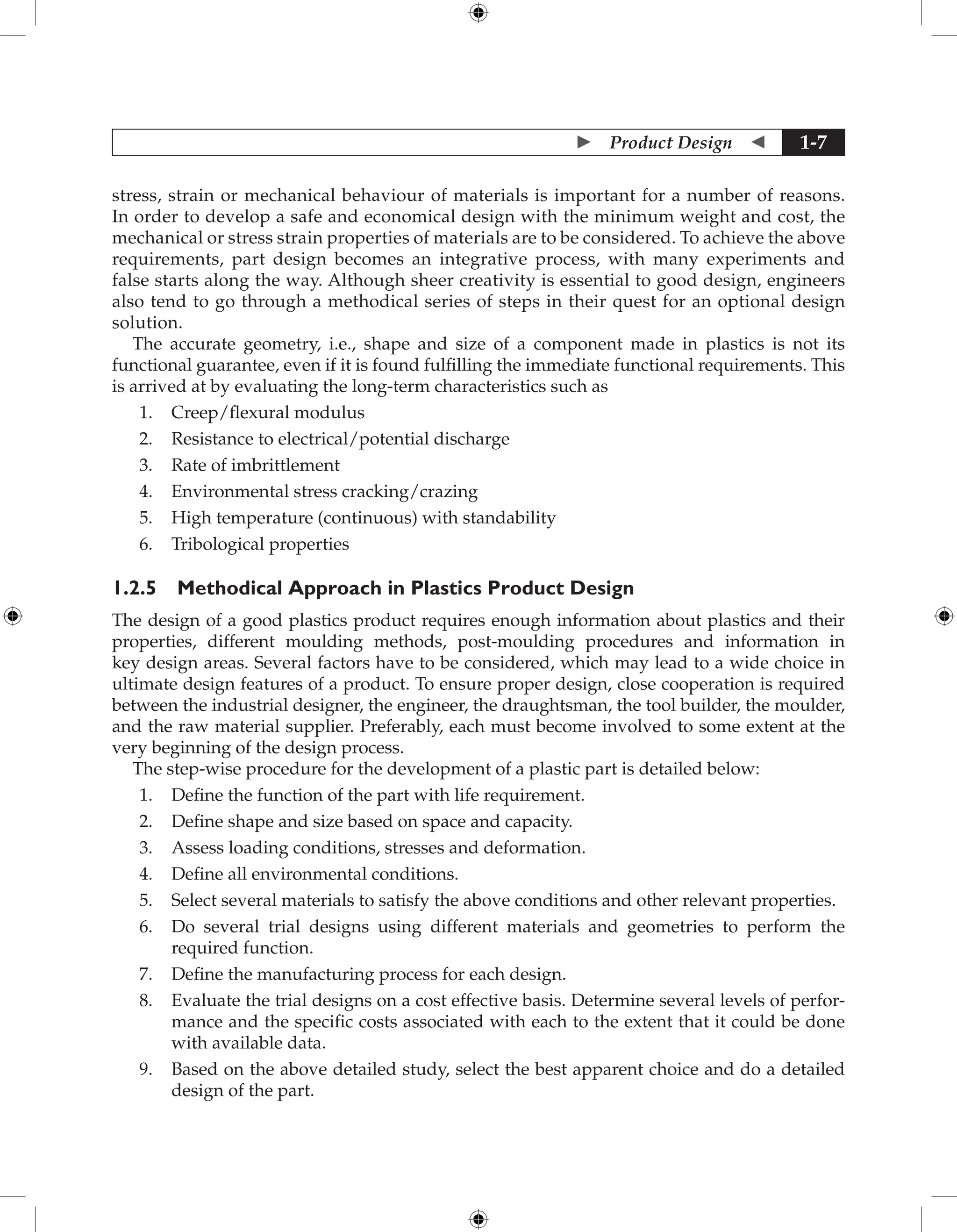

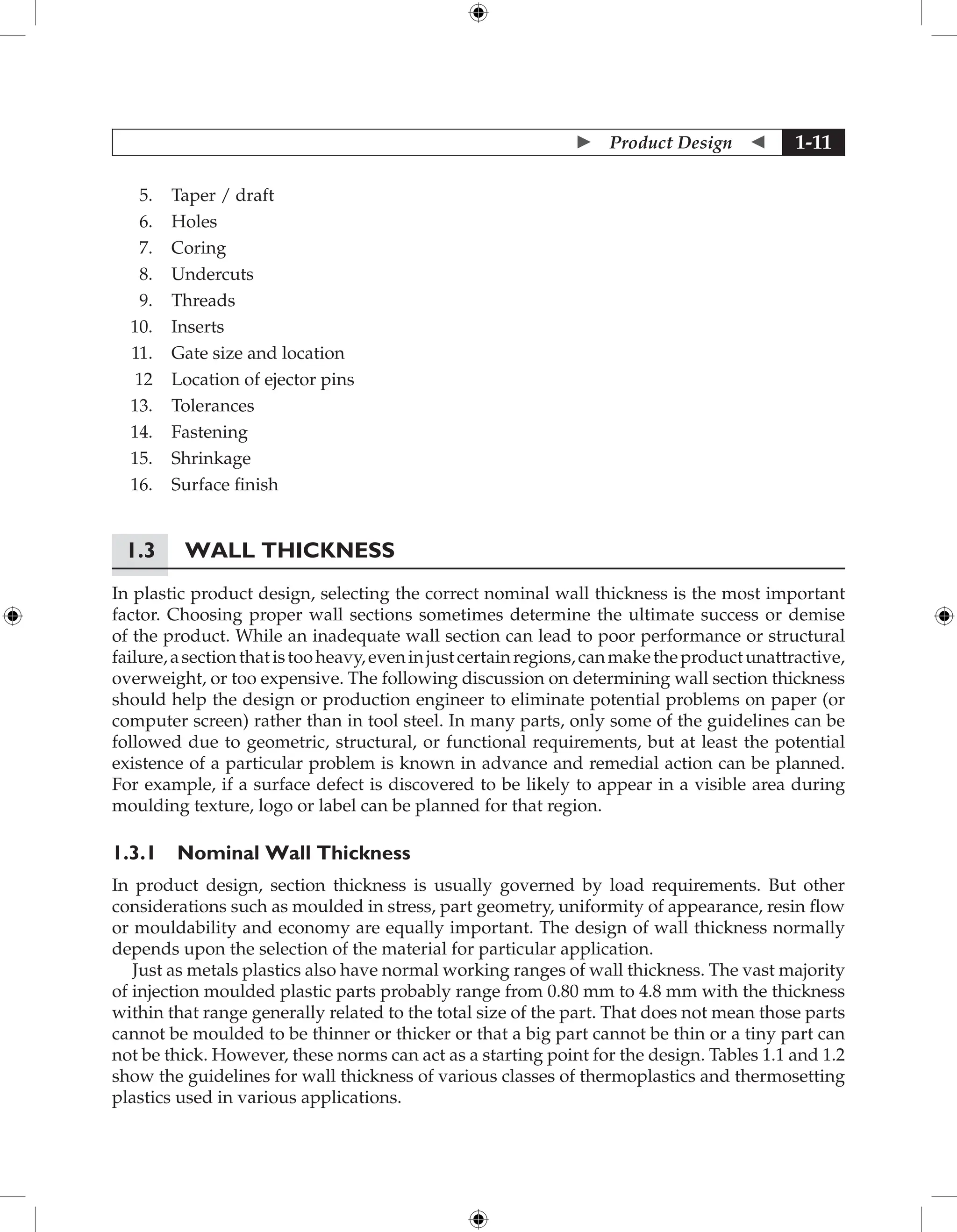

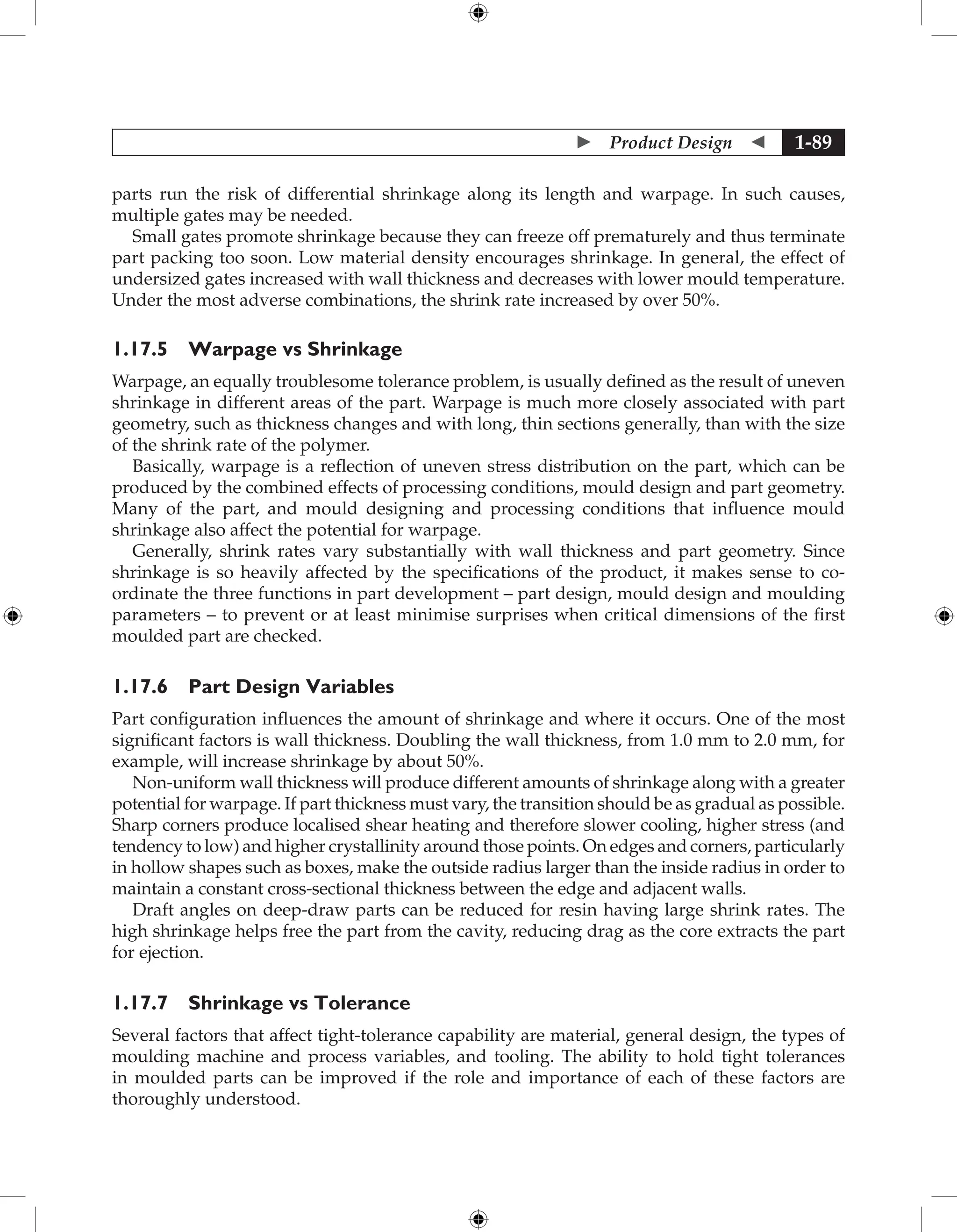

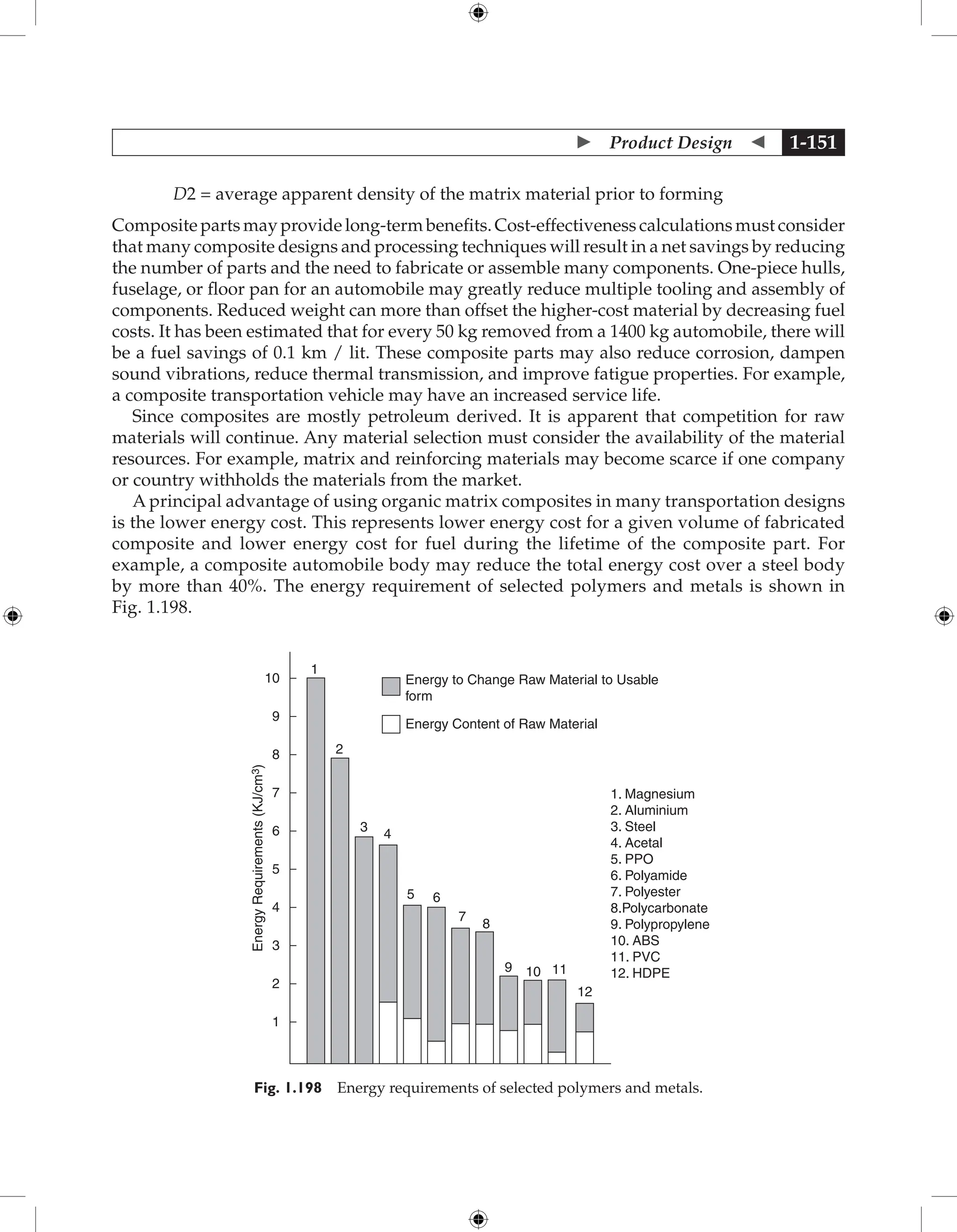

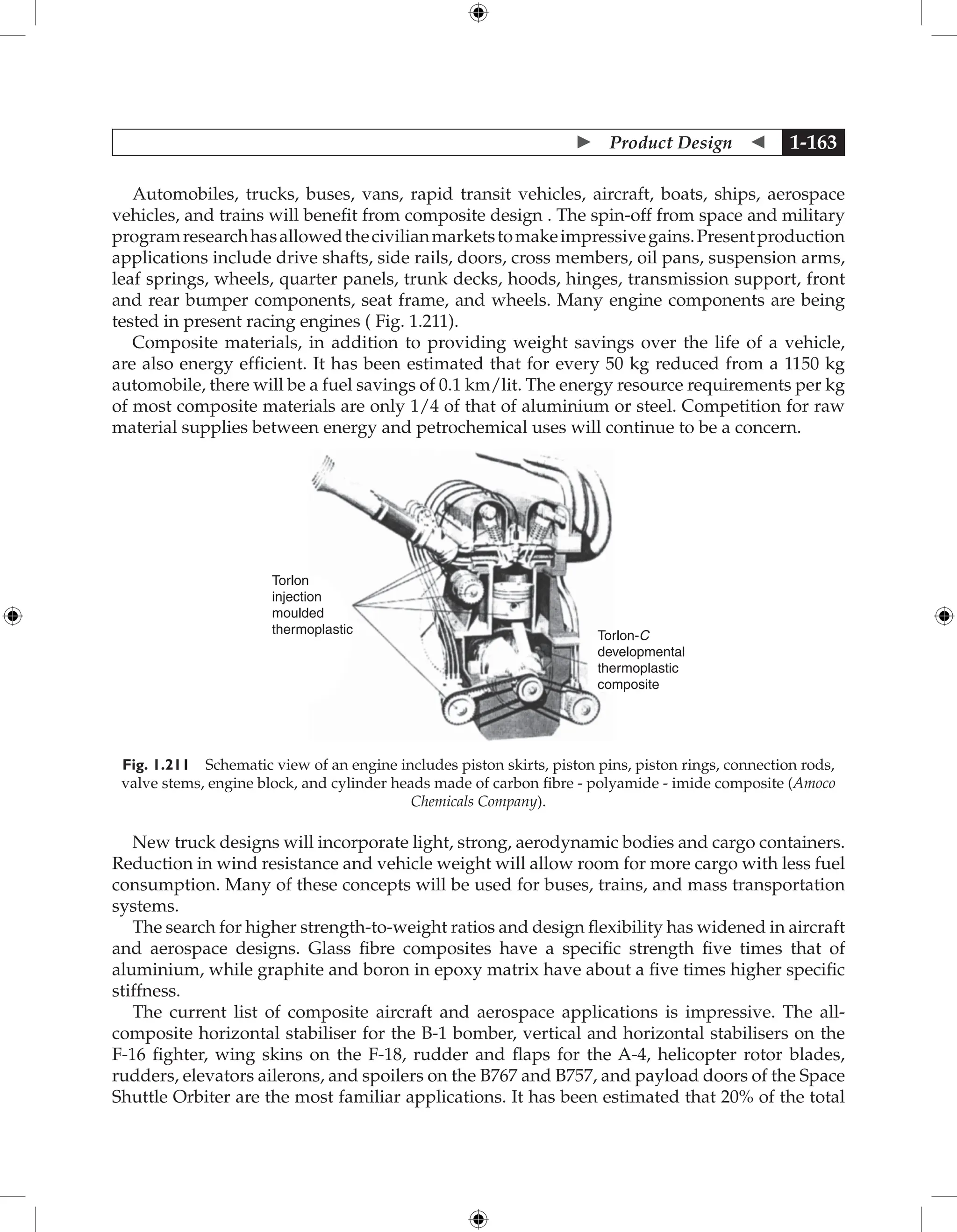

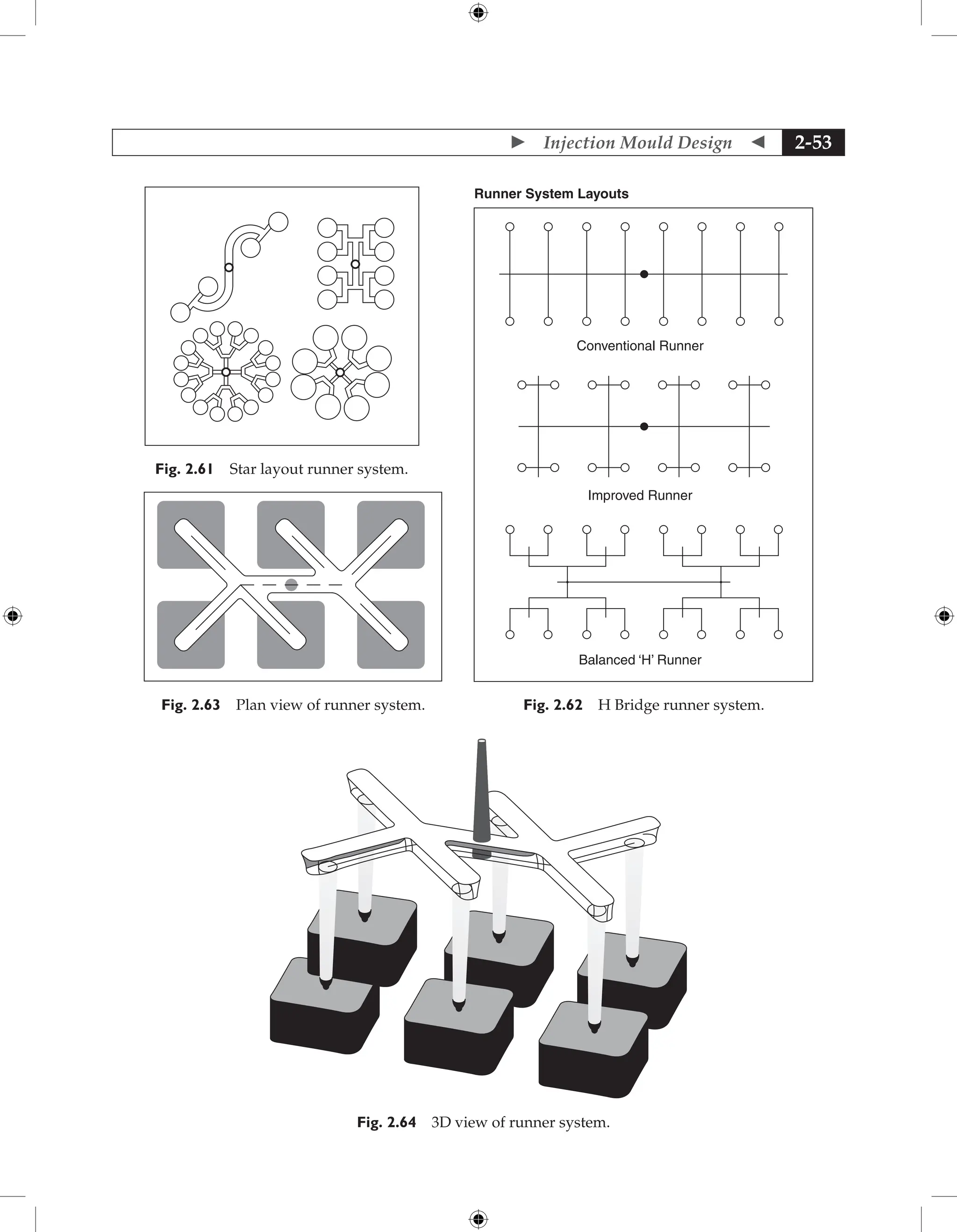

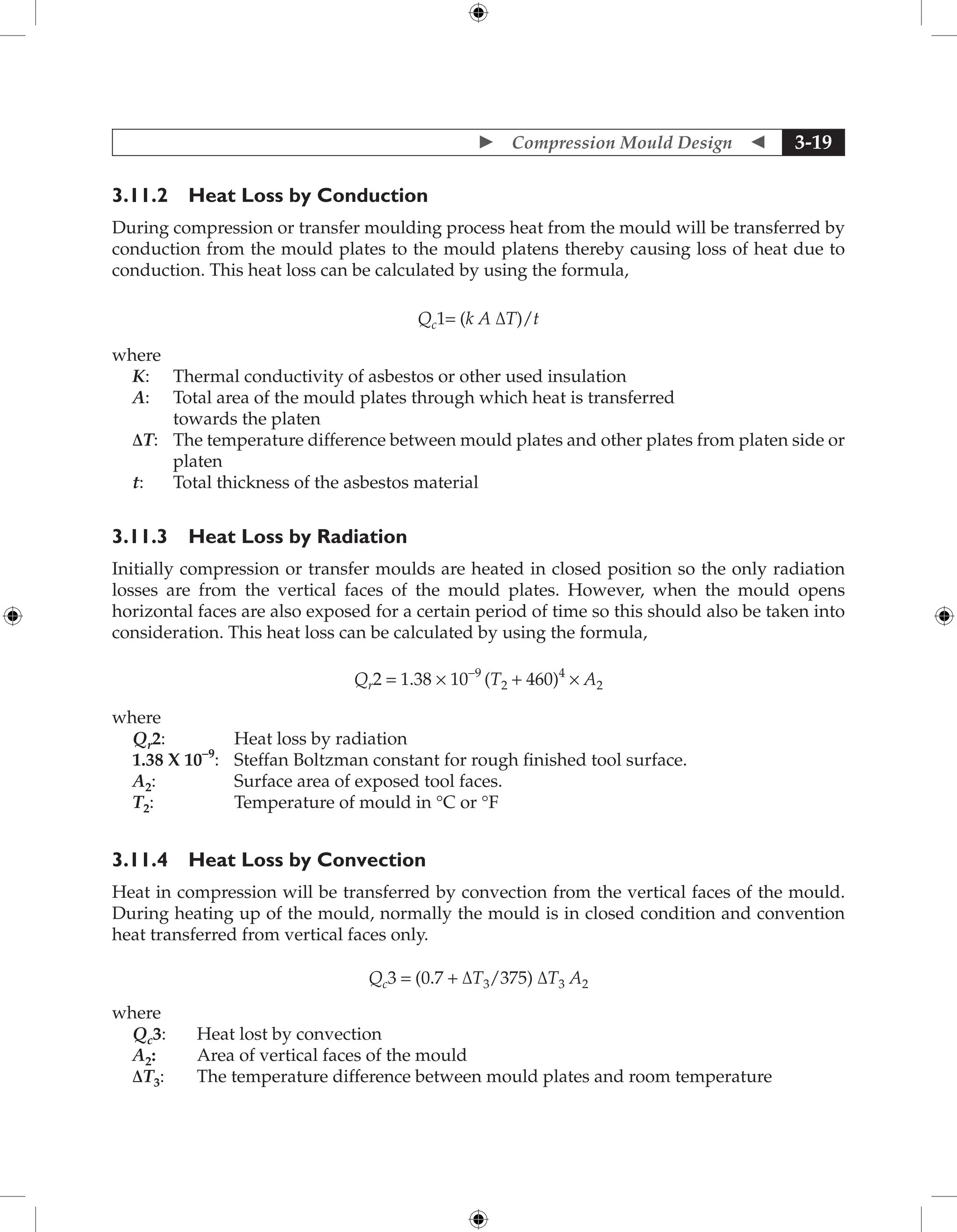

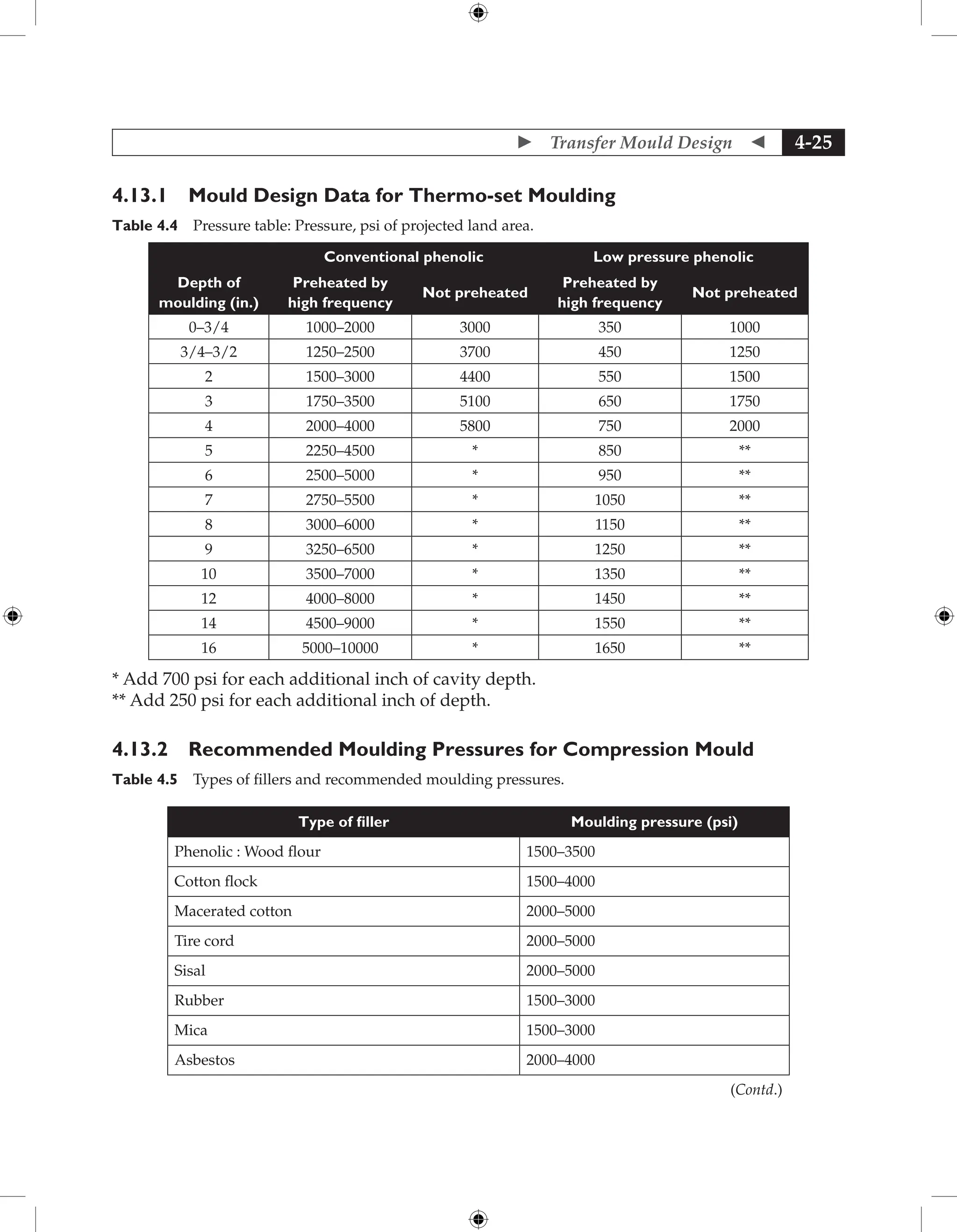

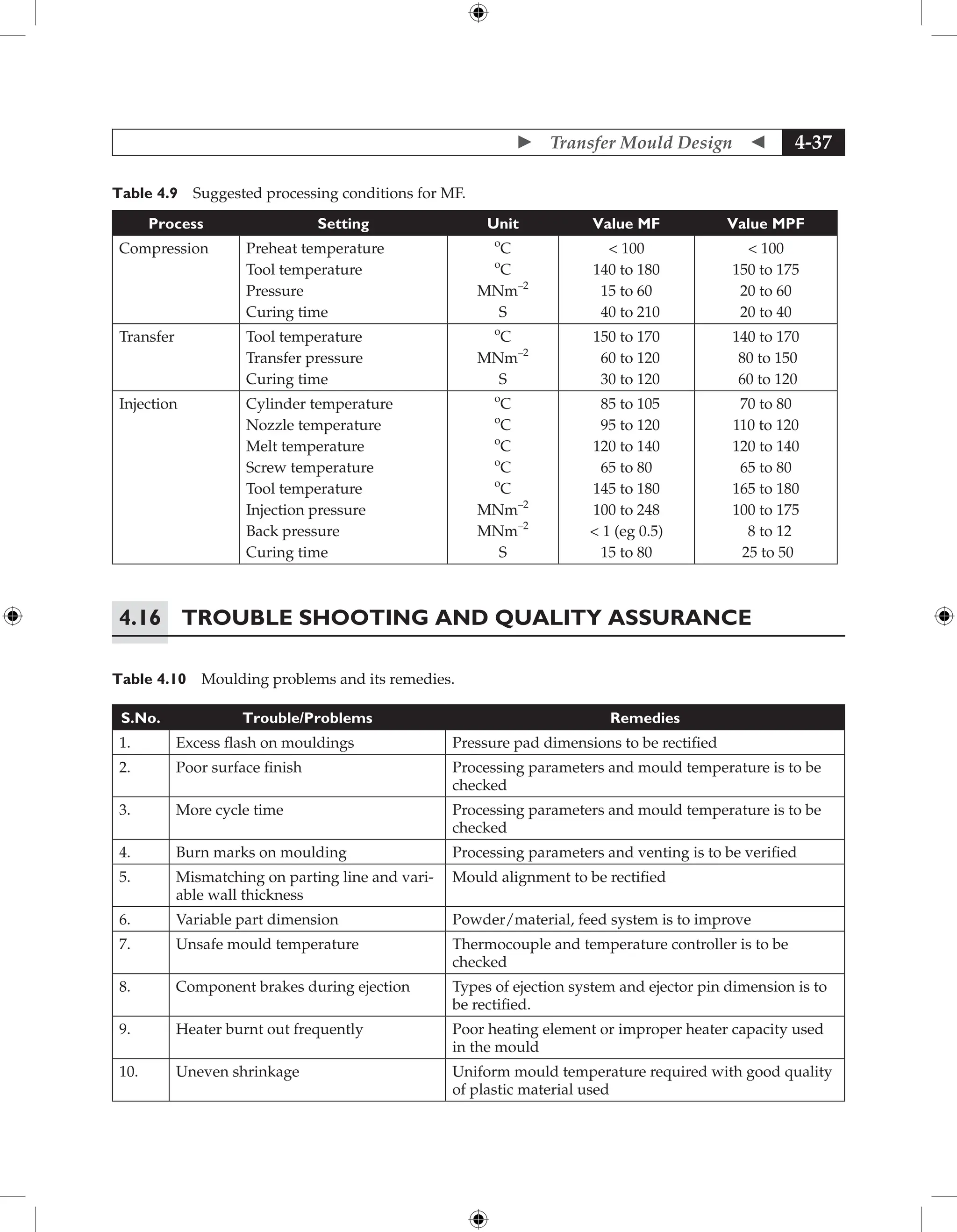

![ Fundamentals of Plastics Mould Design

2-56

[sec]

0

0.09

0.18

0.26

0.35

0.44

0.53

0.62

0.71

0.79

20 mm

0.88

.55

.16

.22

Z

Y

X

Fill Time

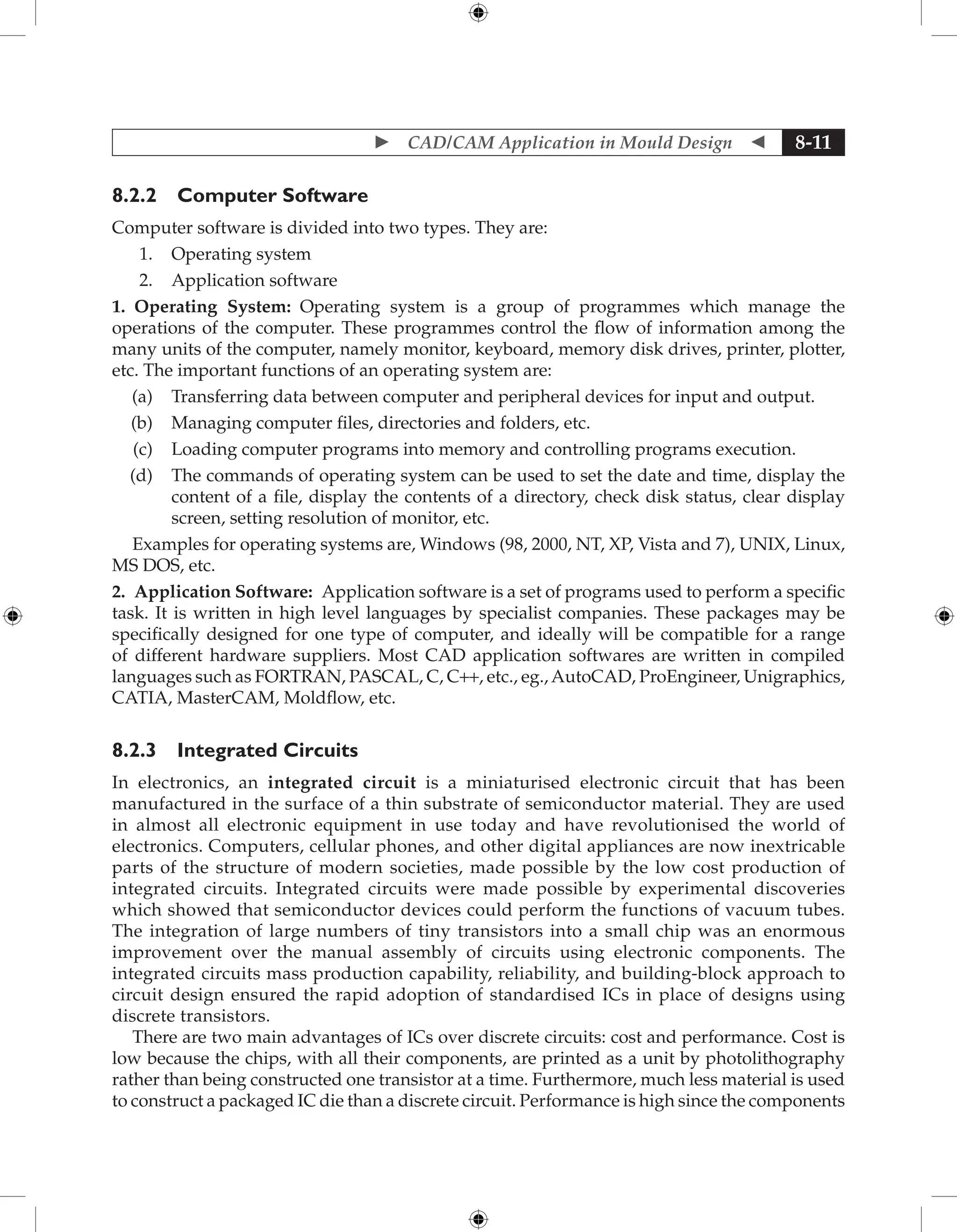

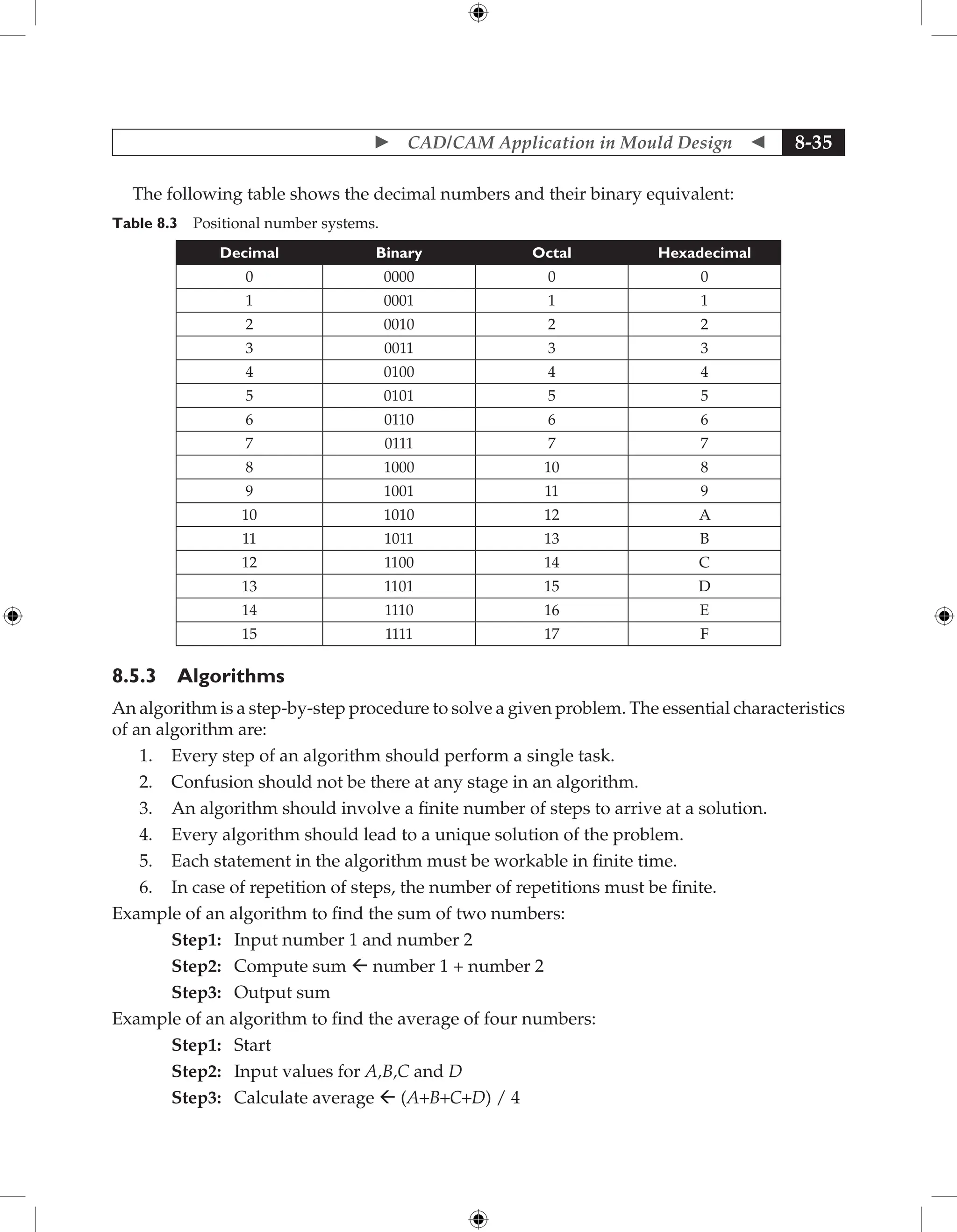

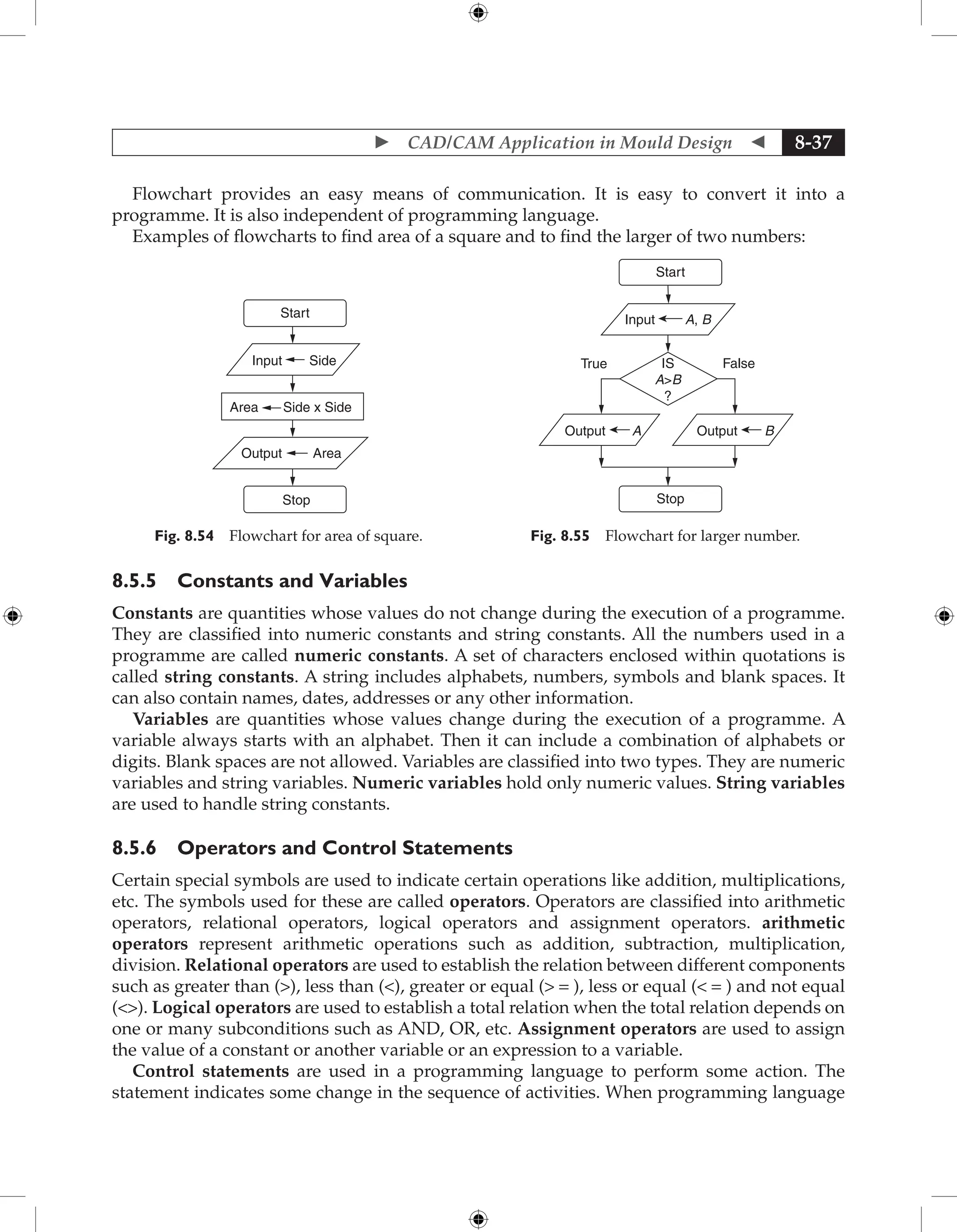

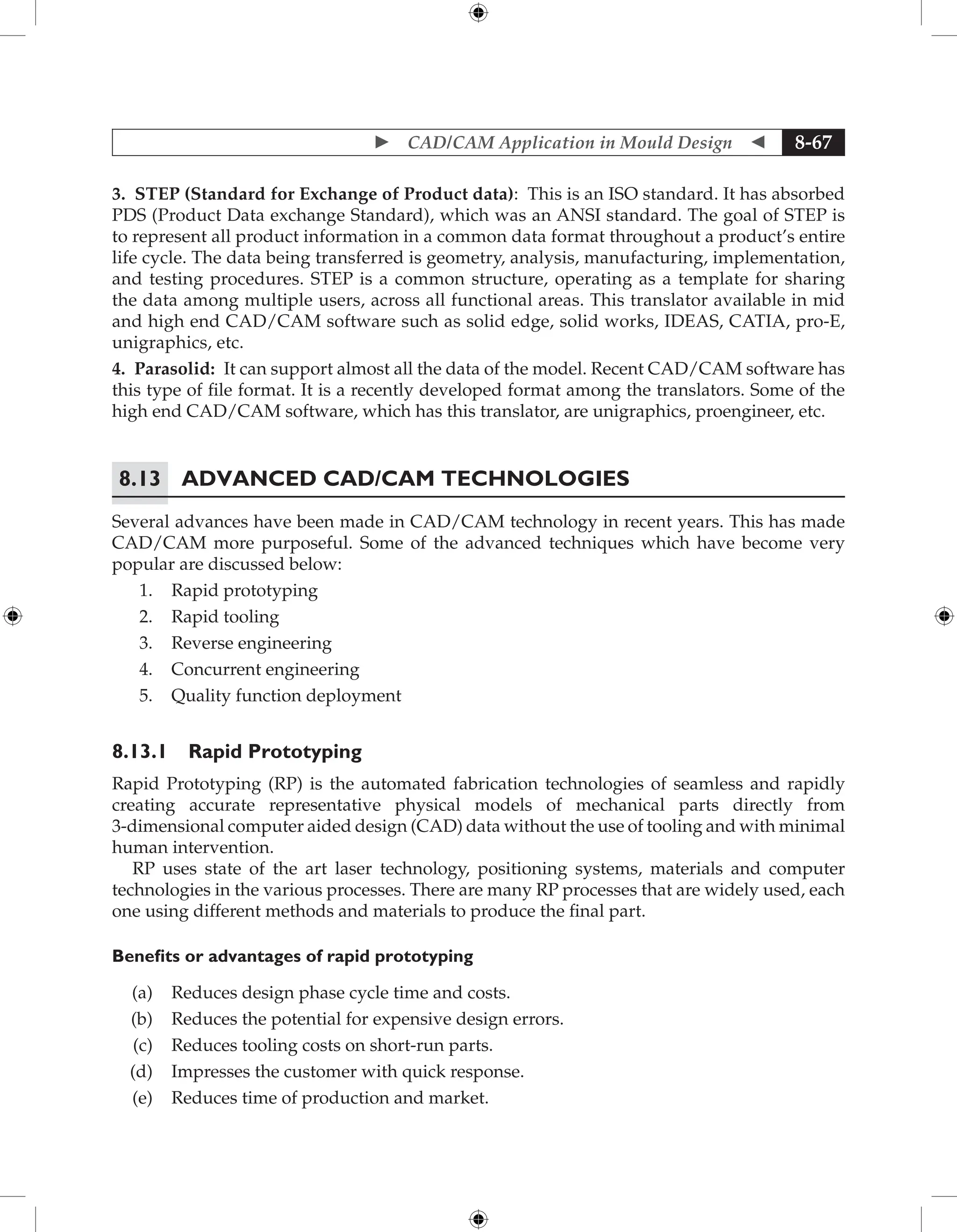

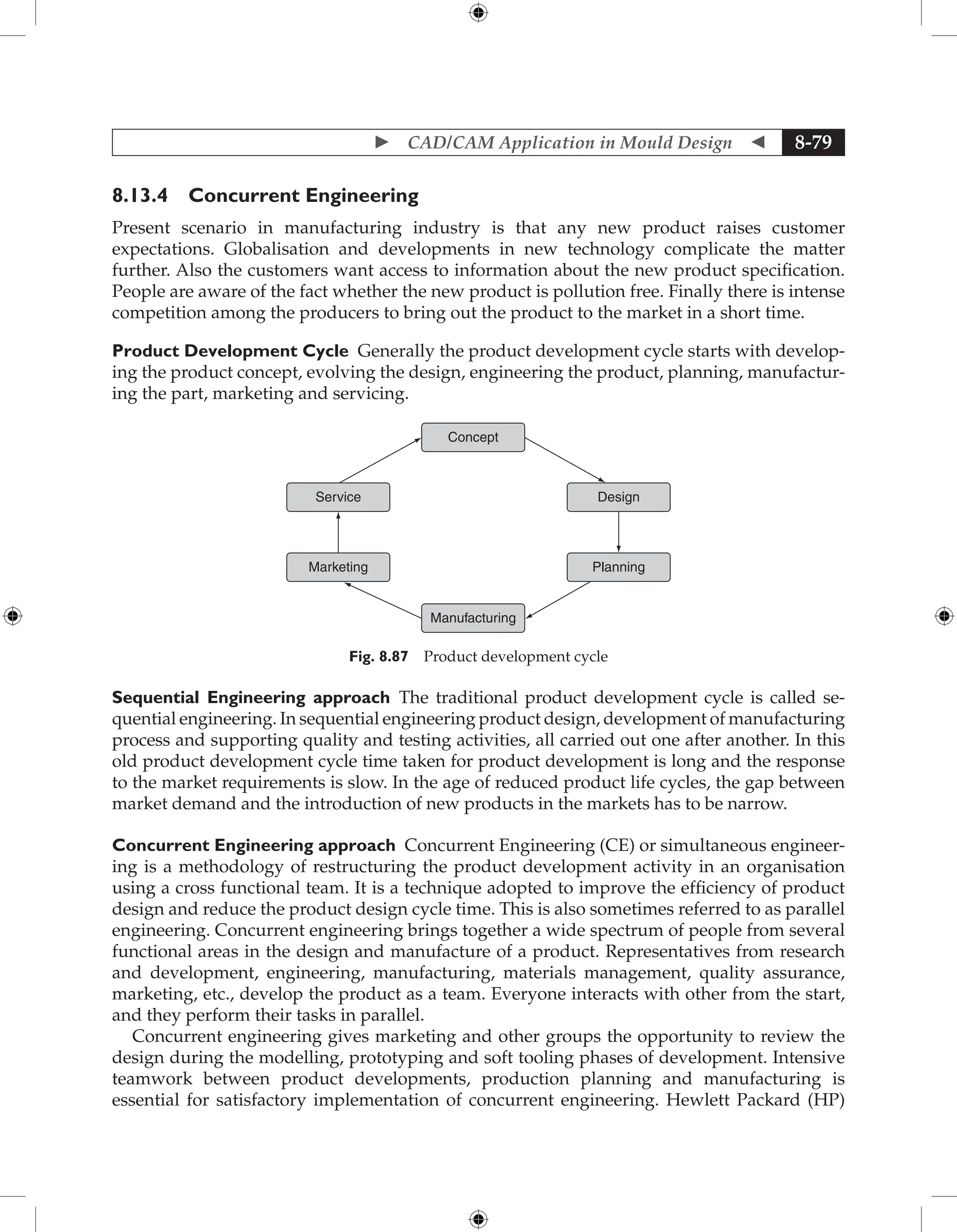

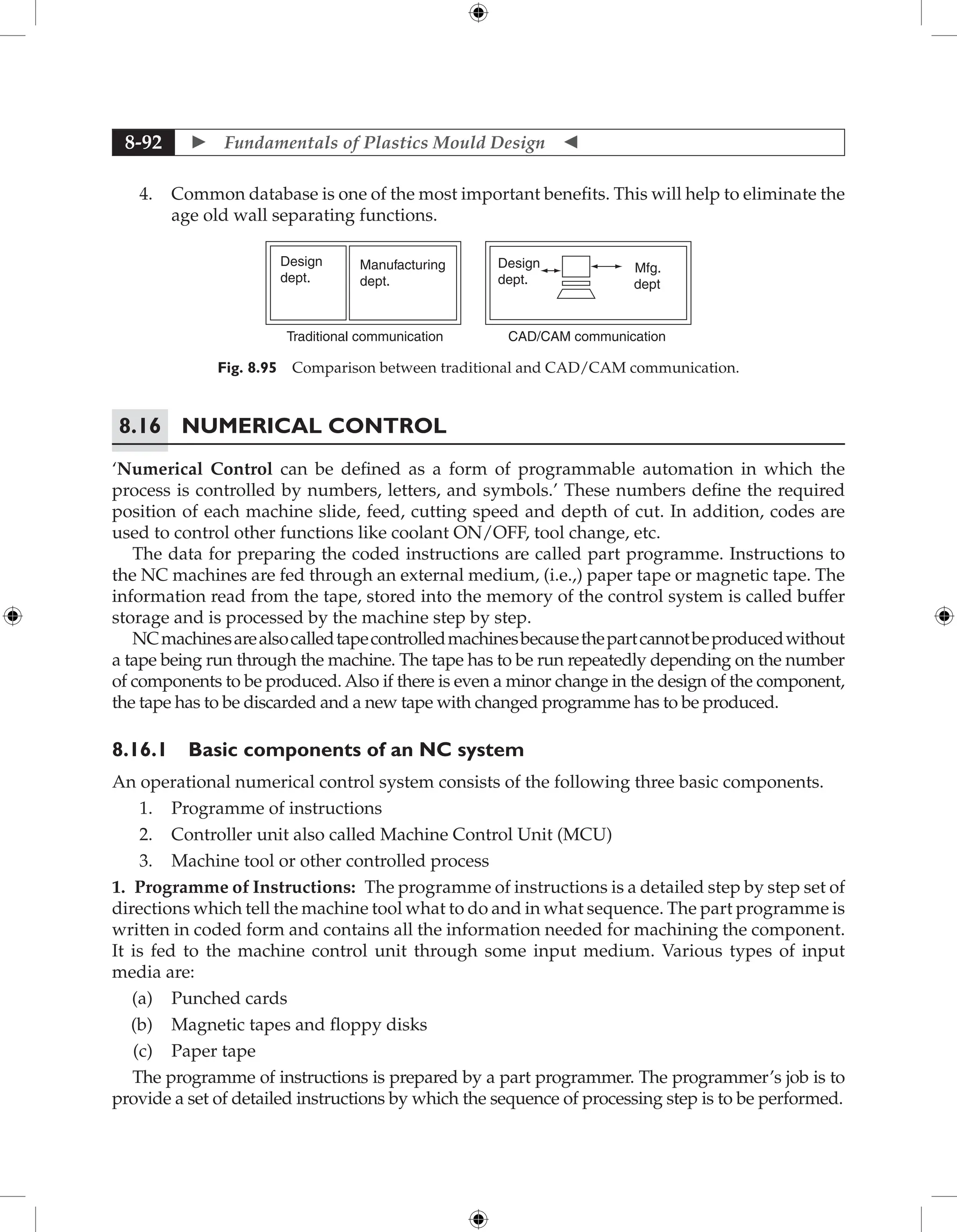

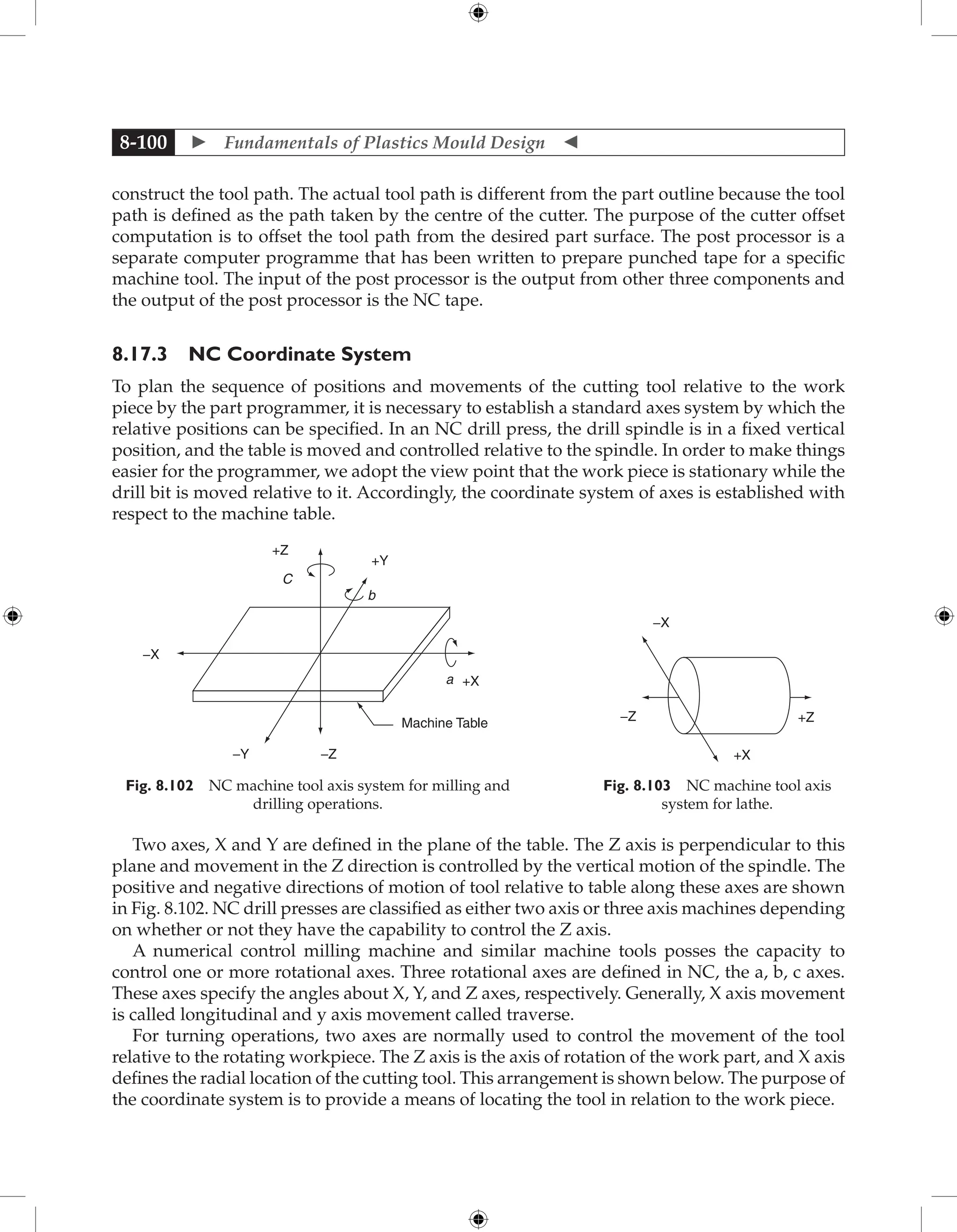

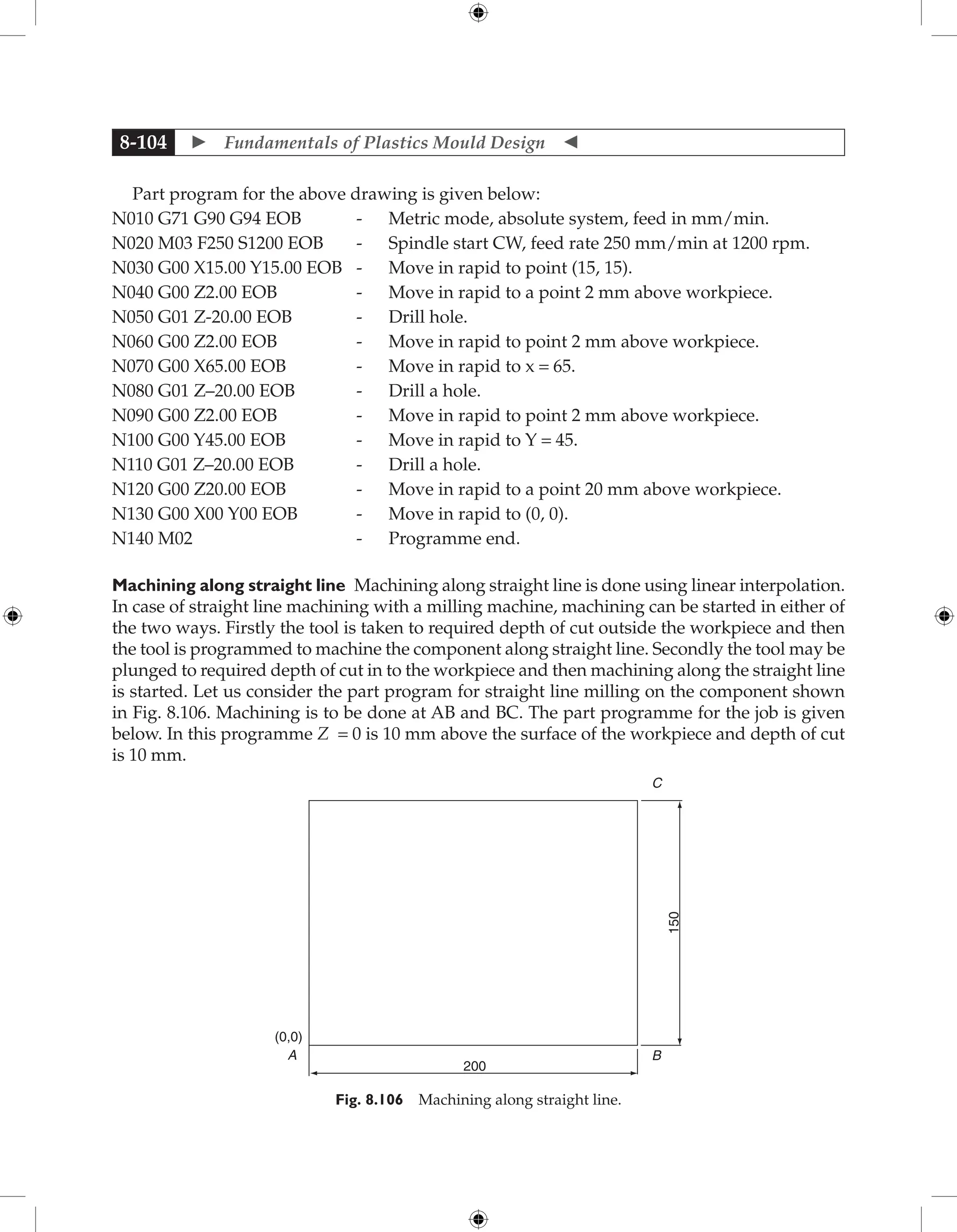

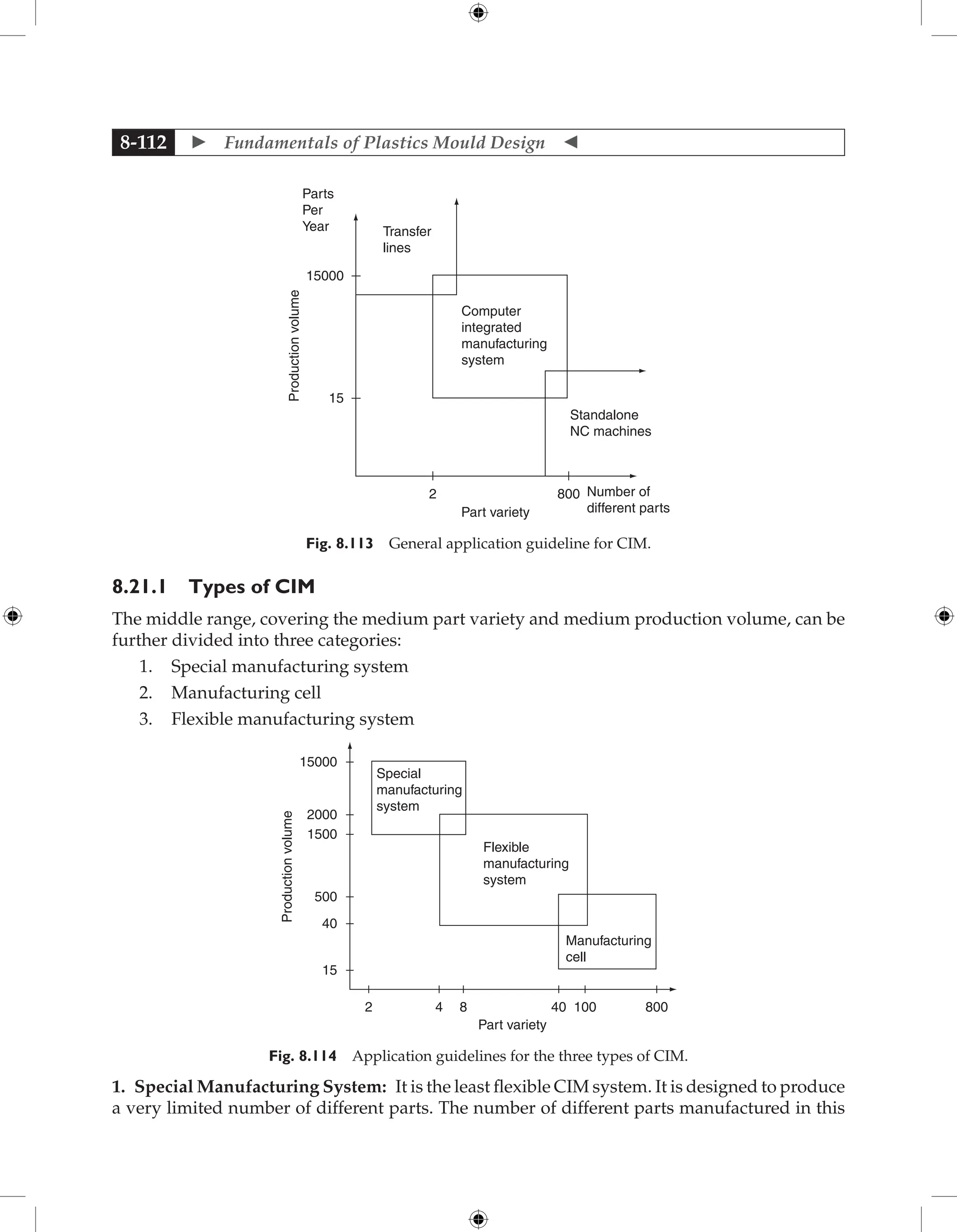

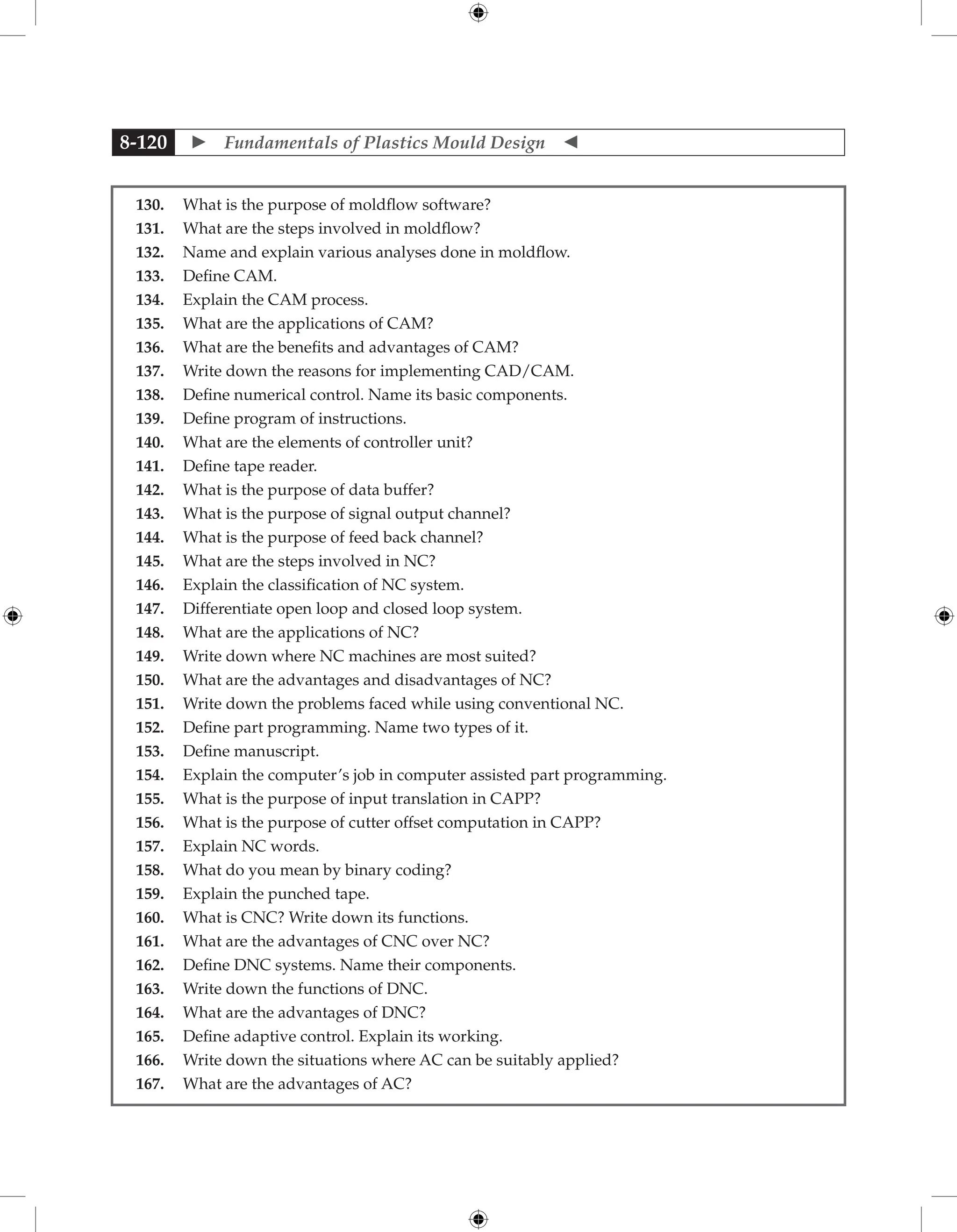

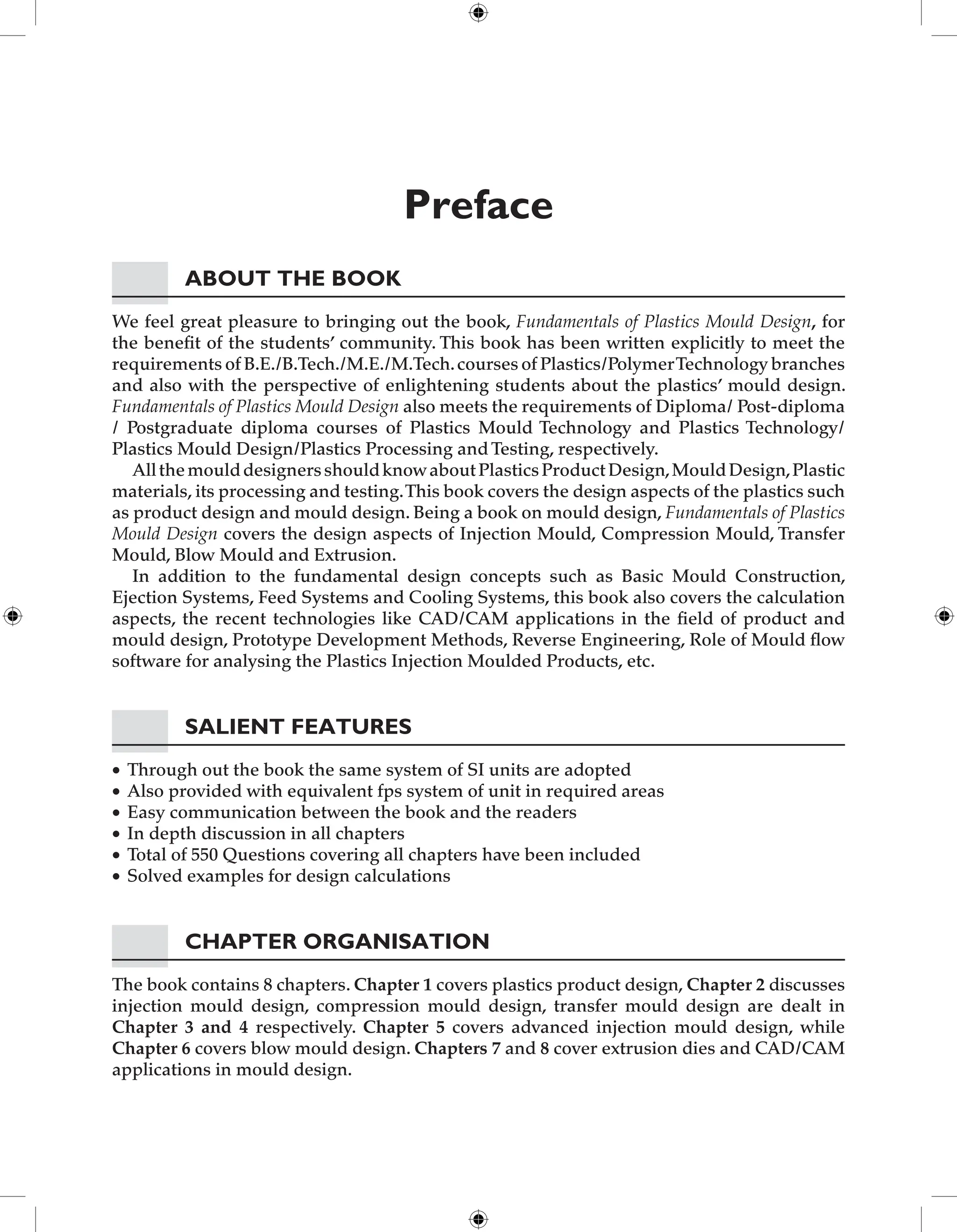

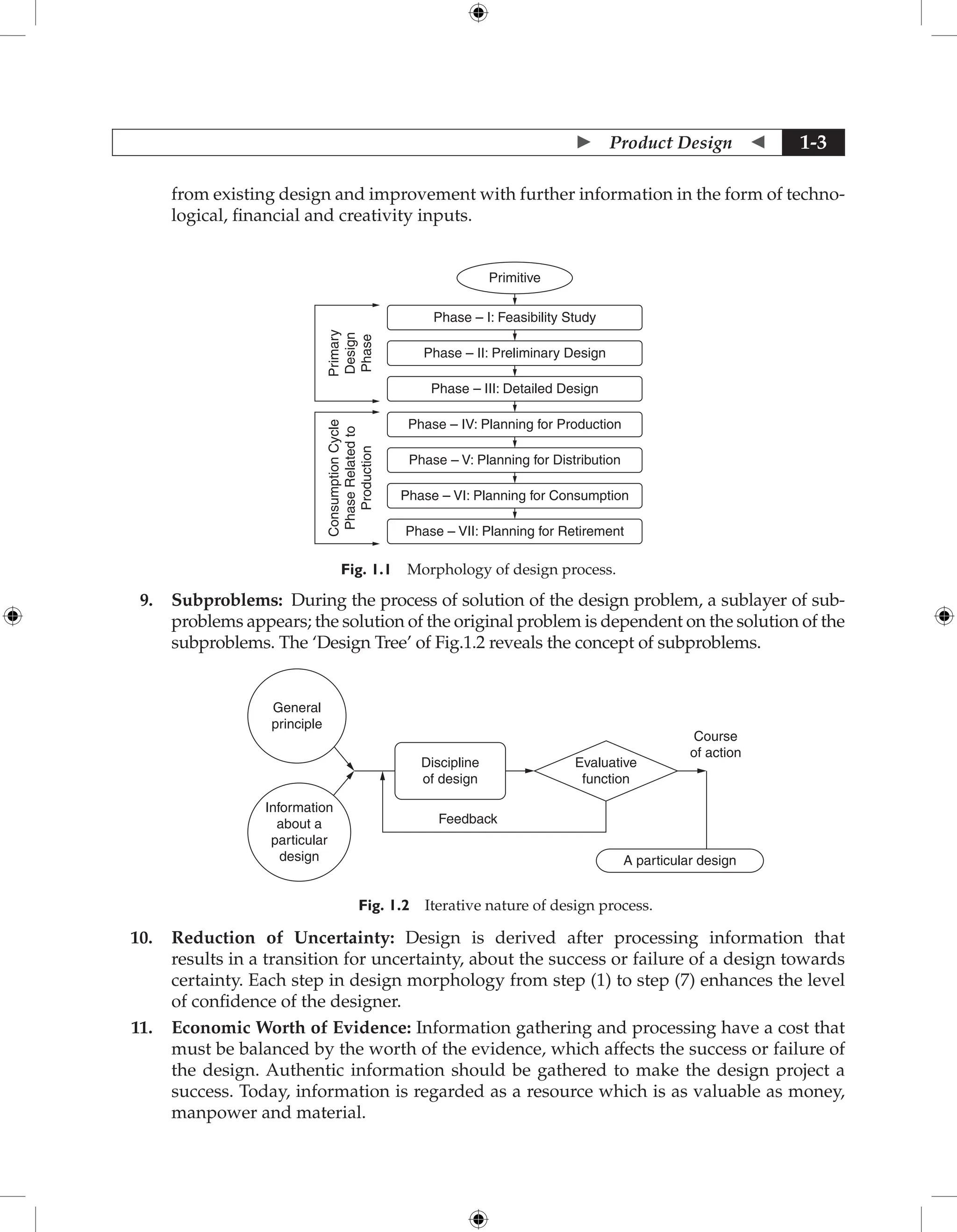

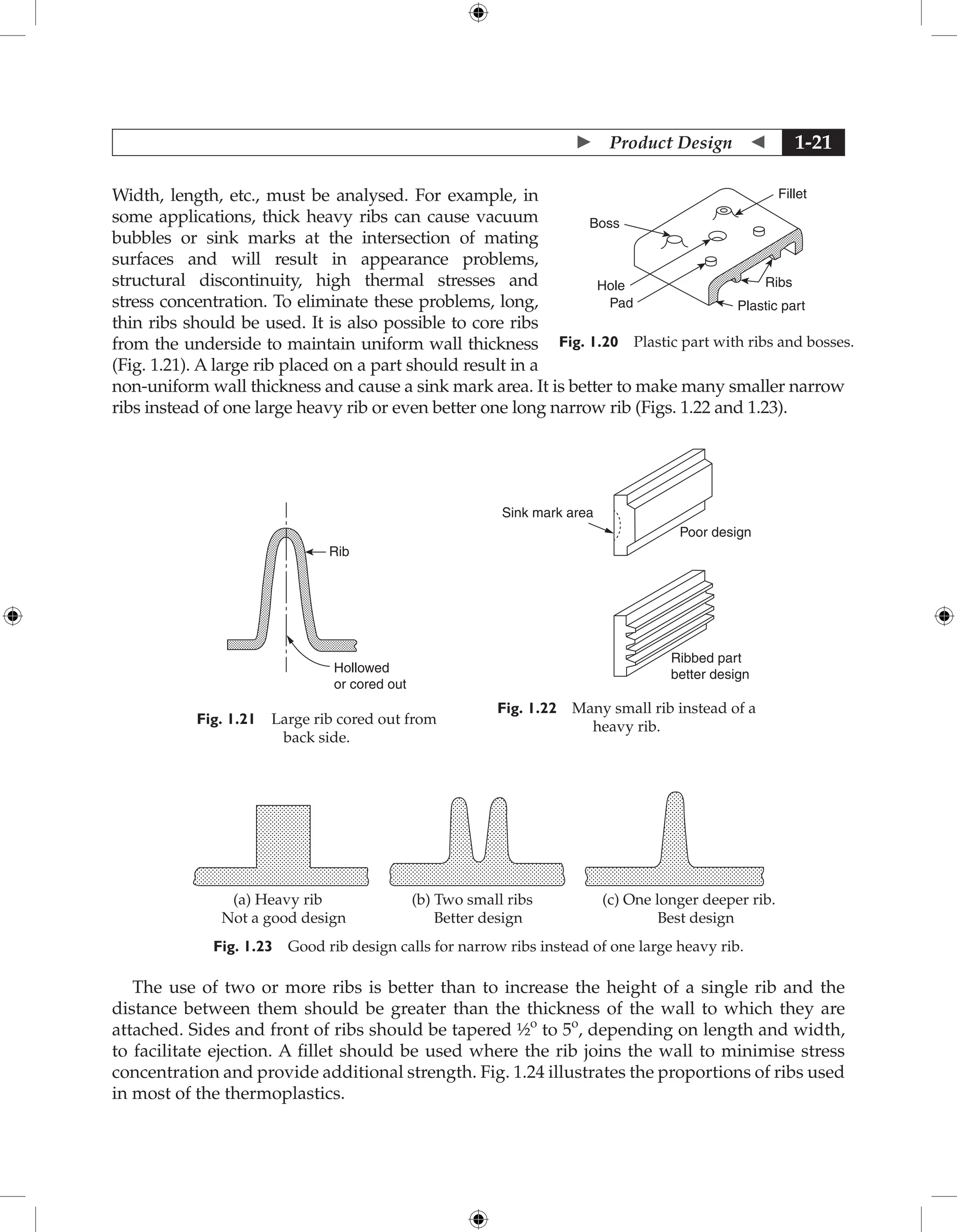

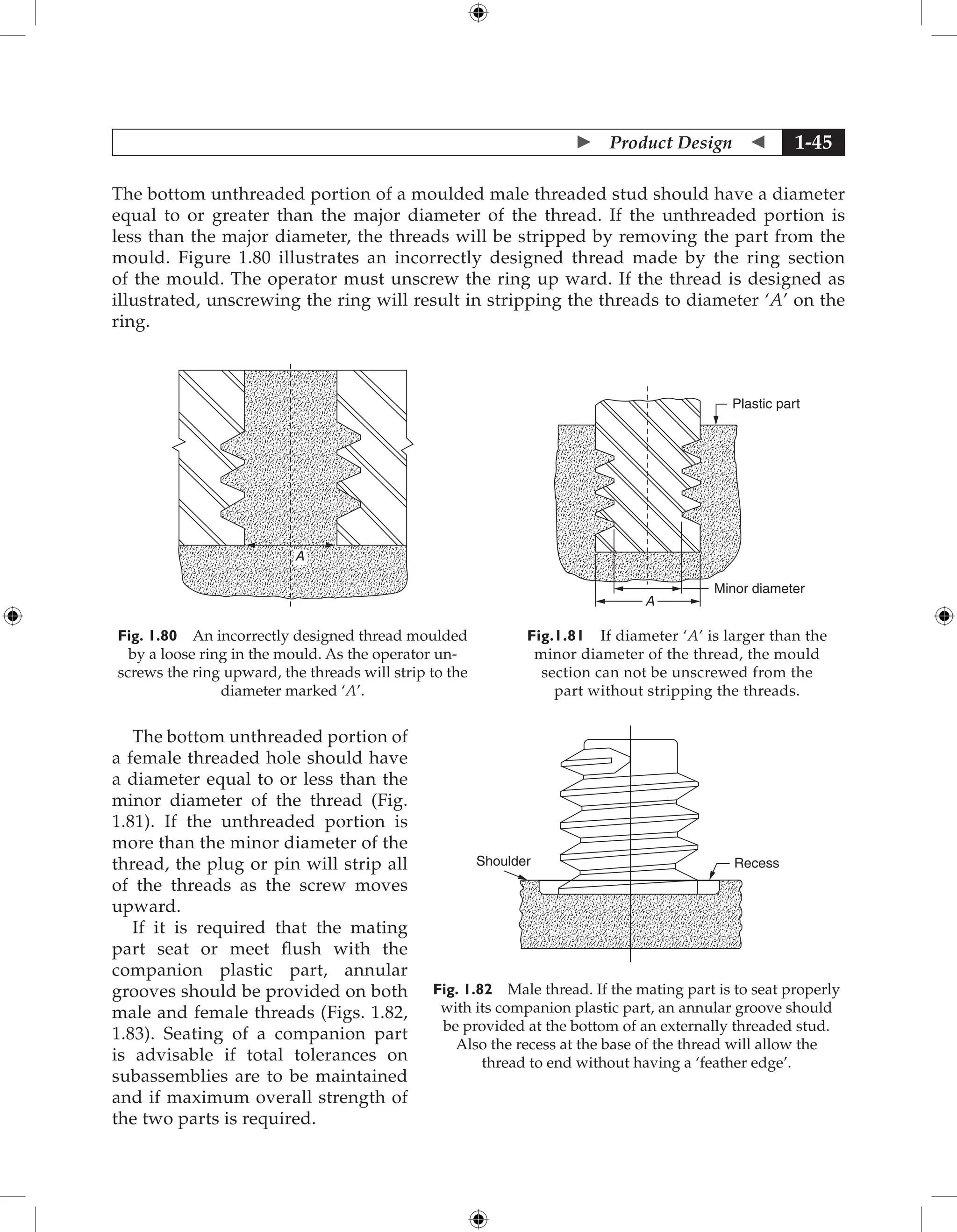

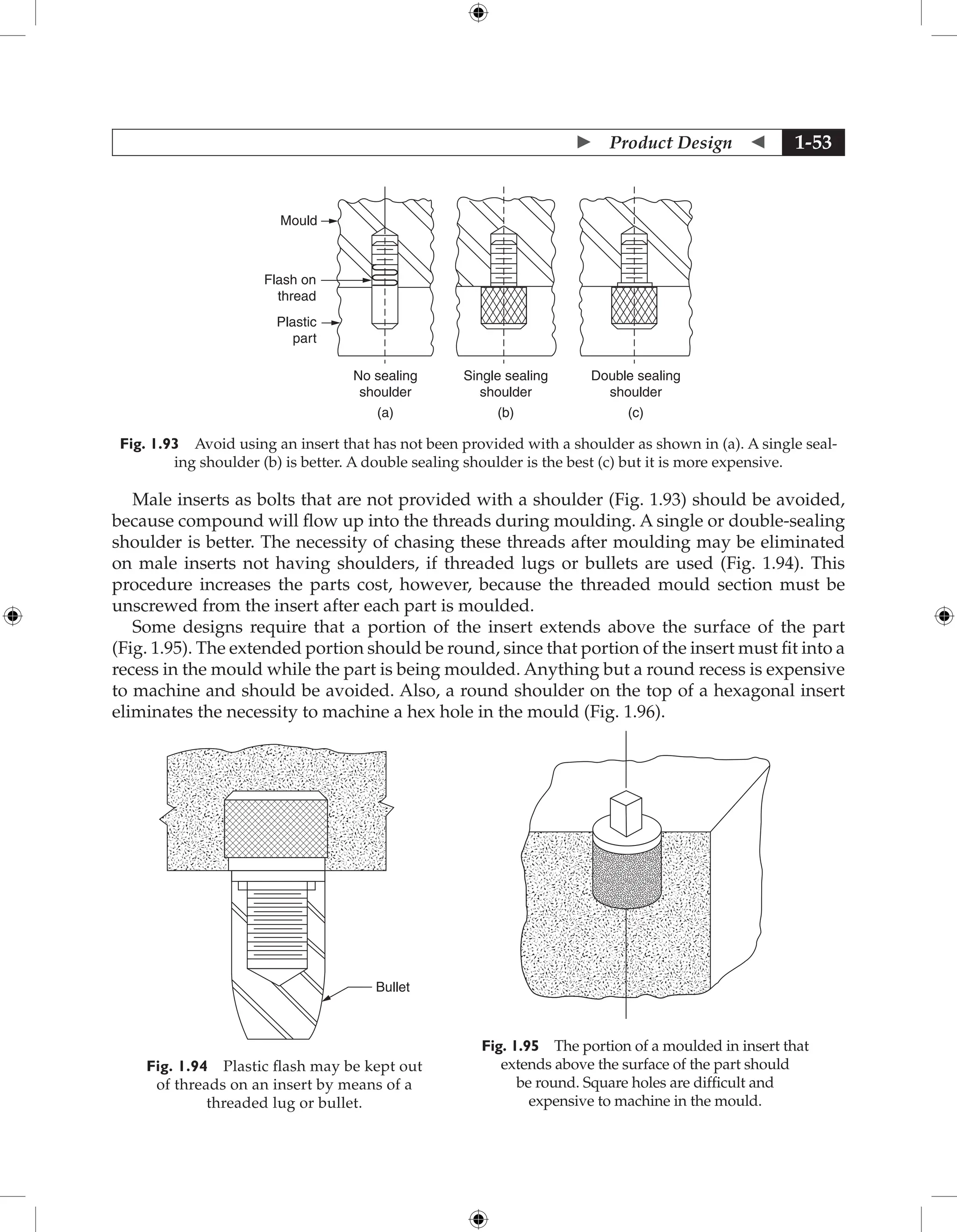

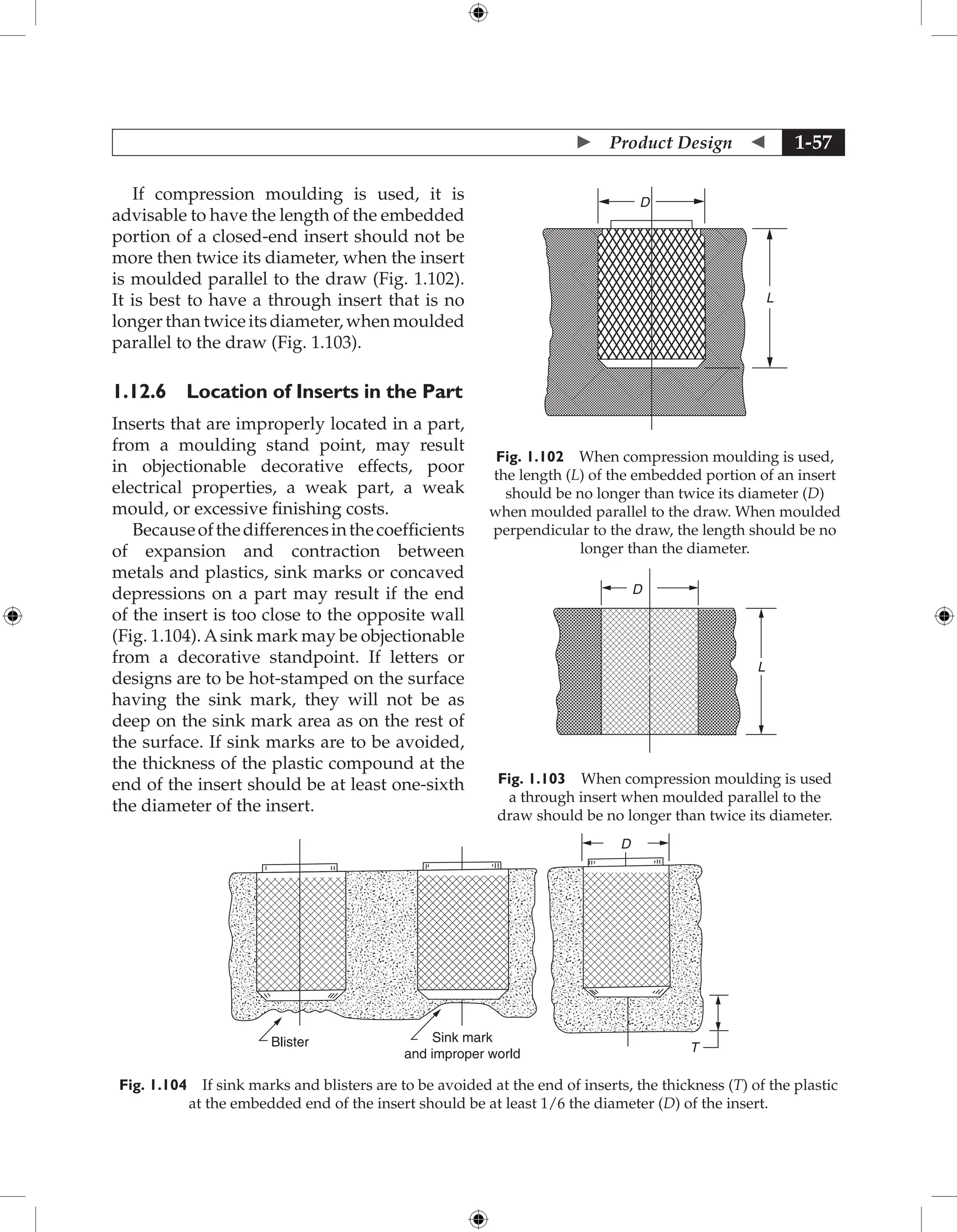

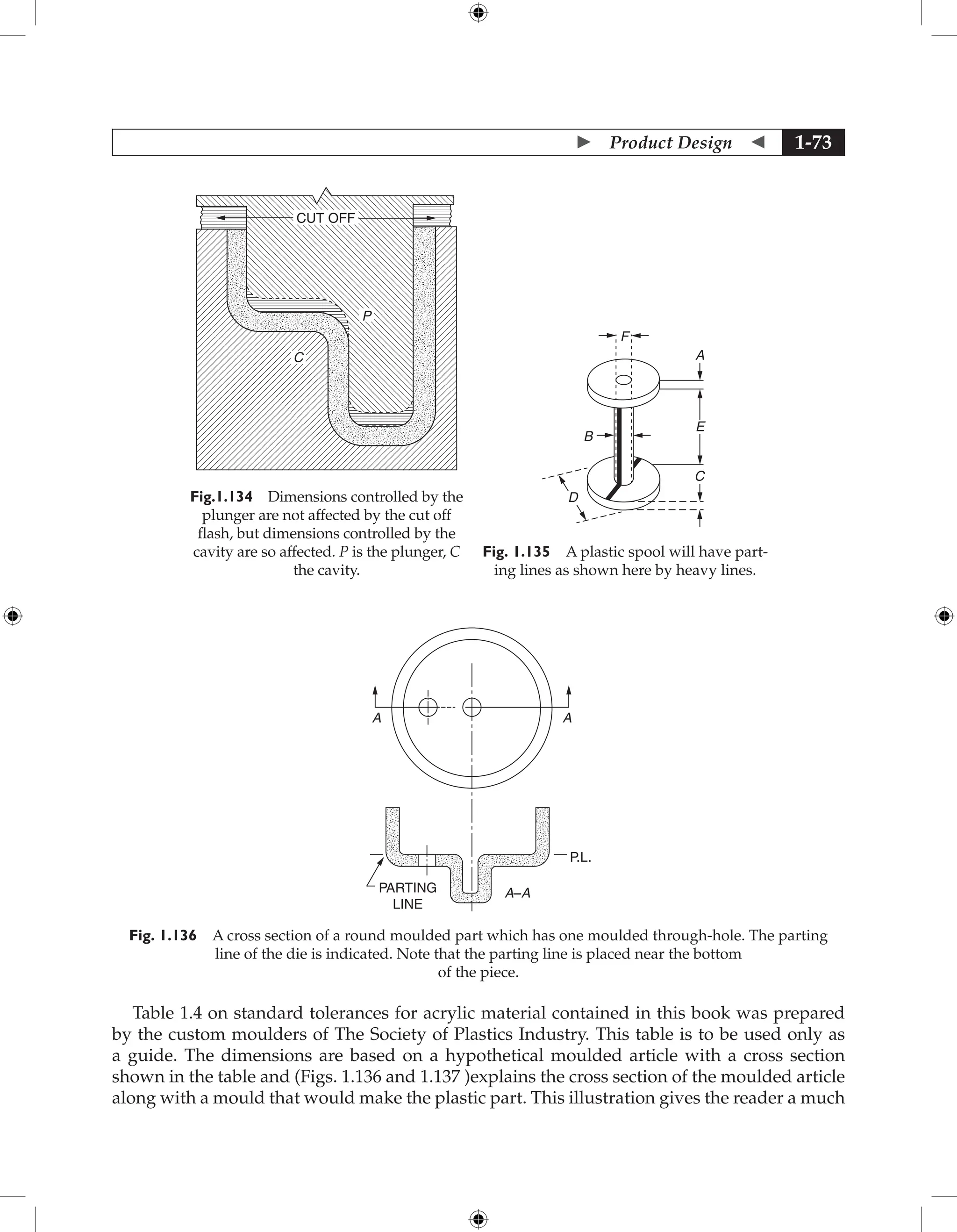

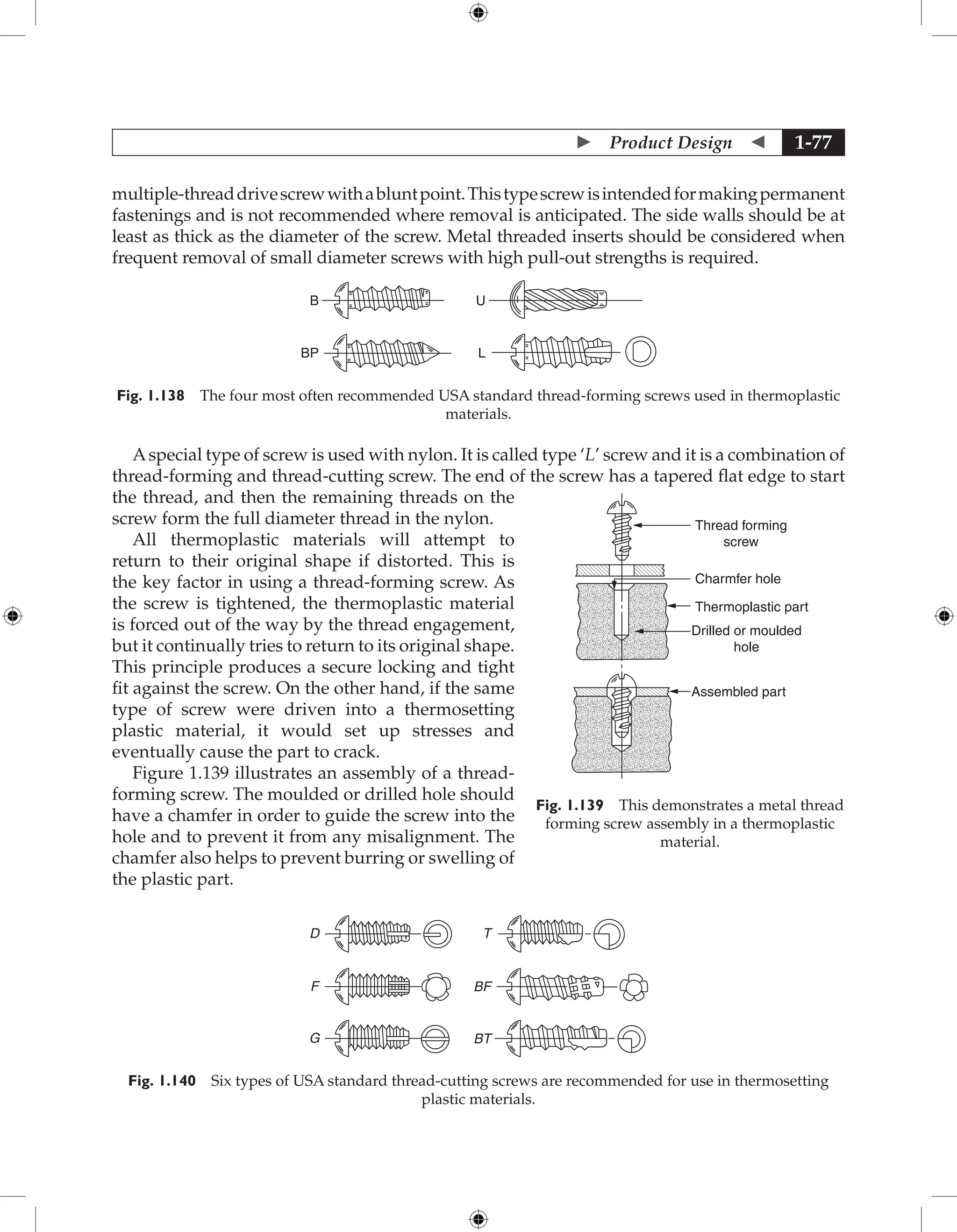

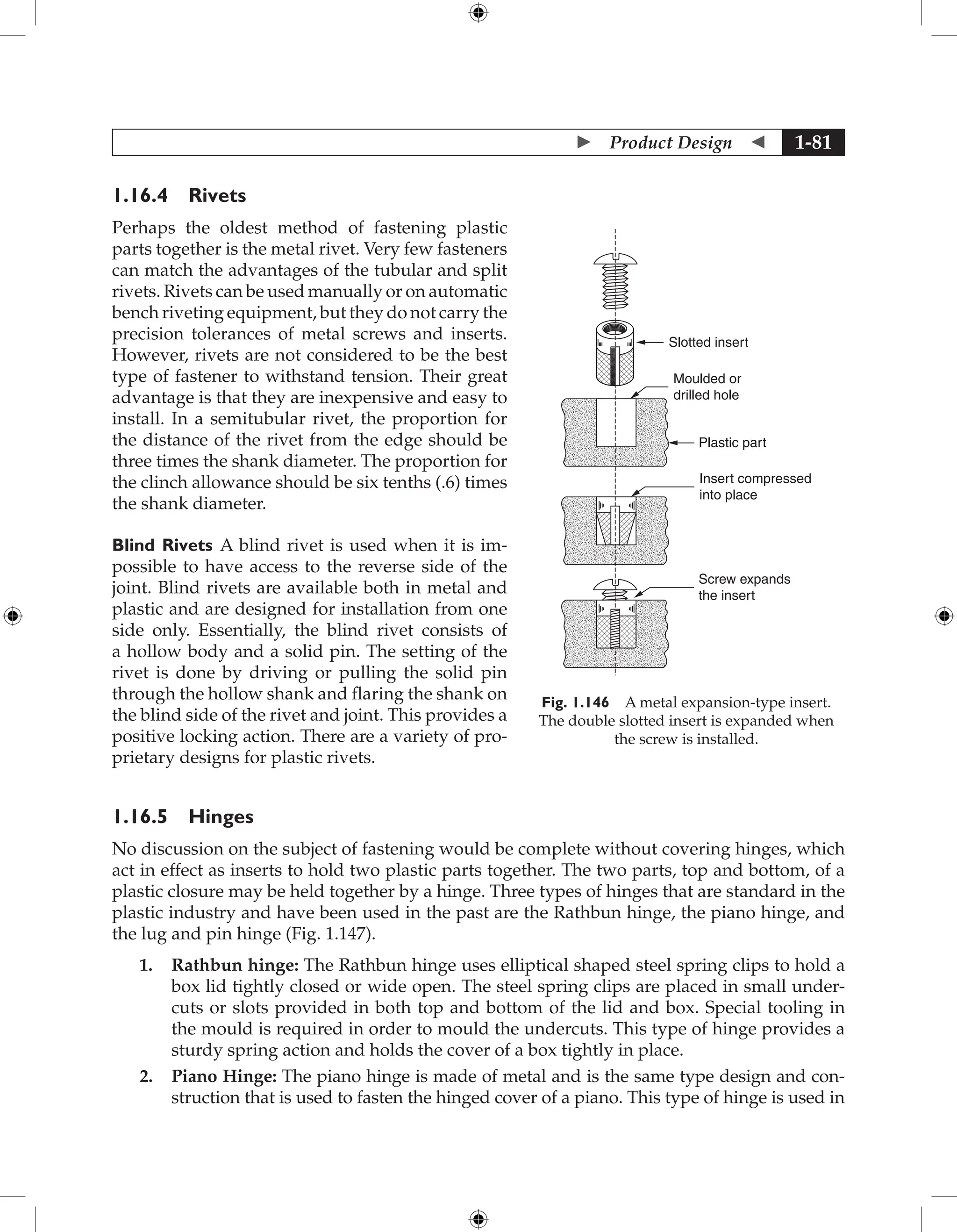

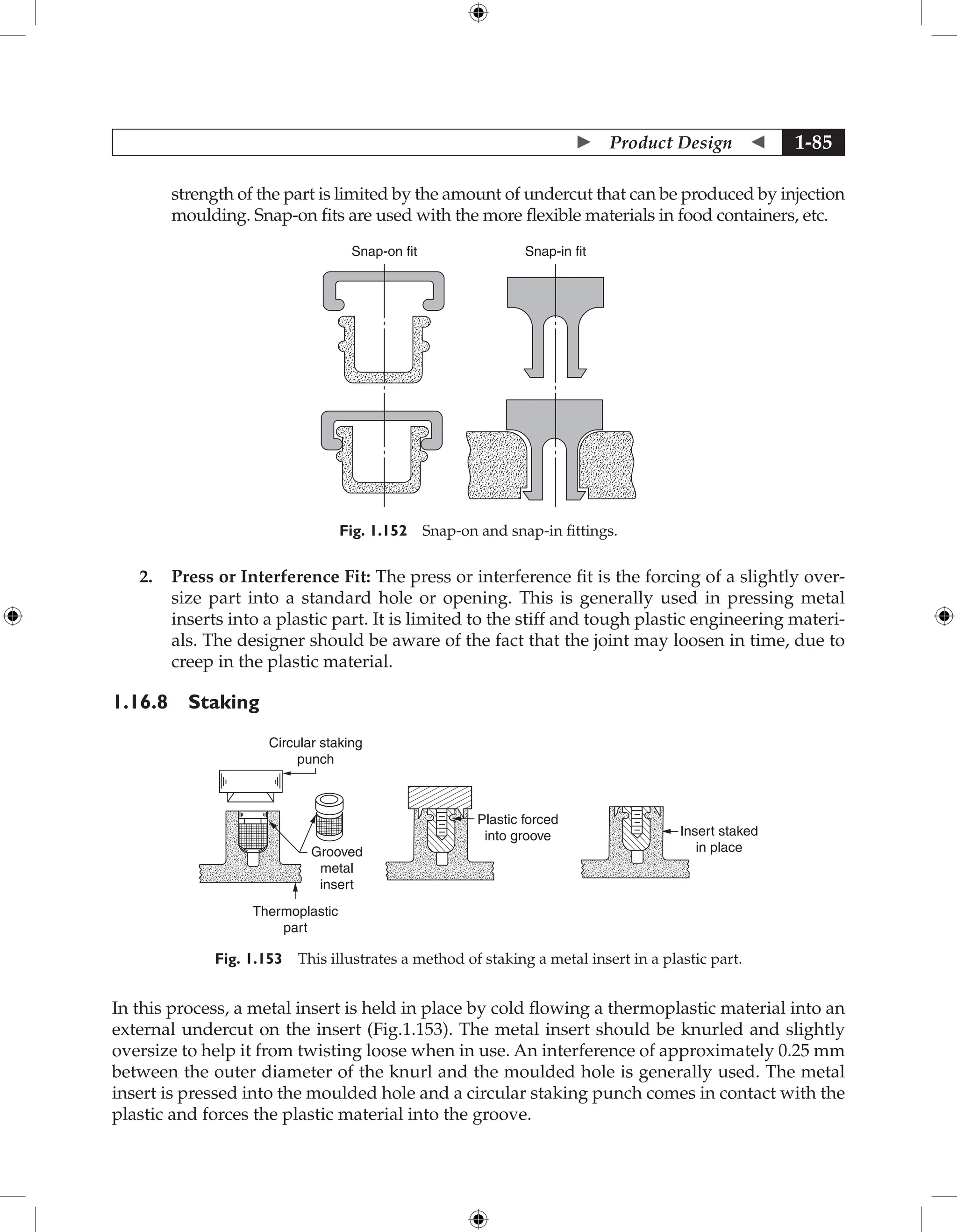

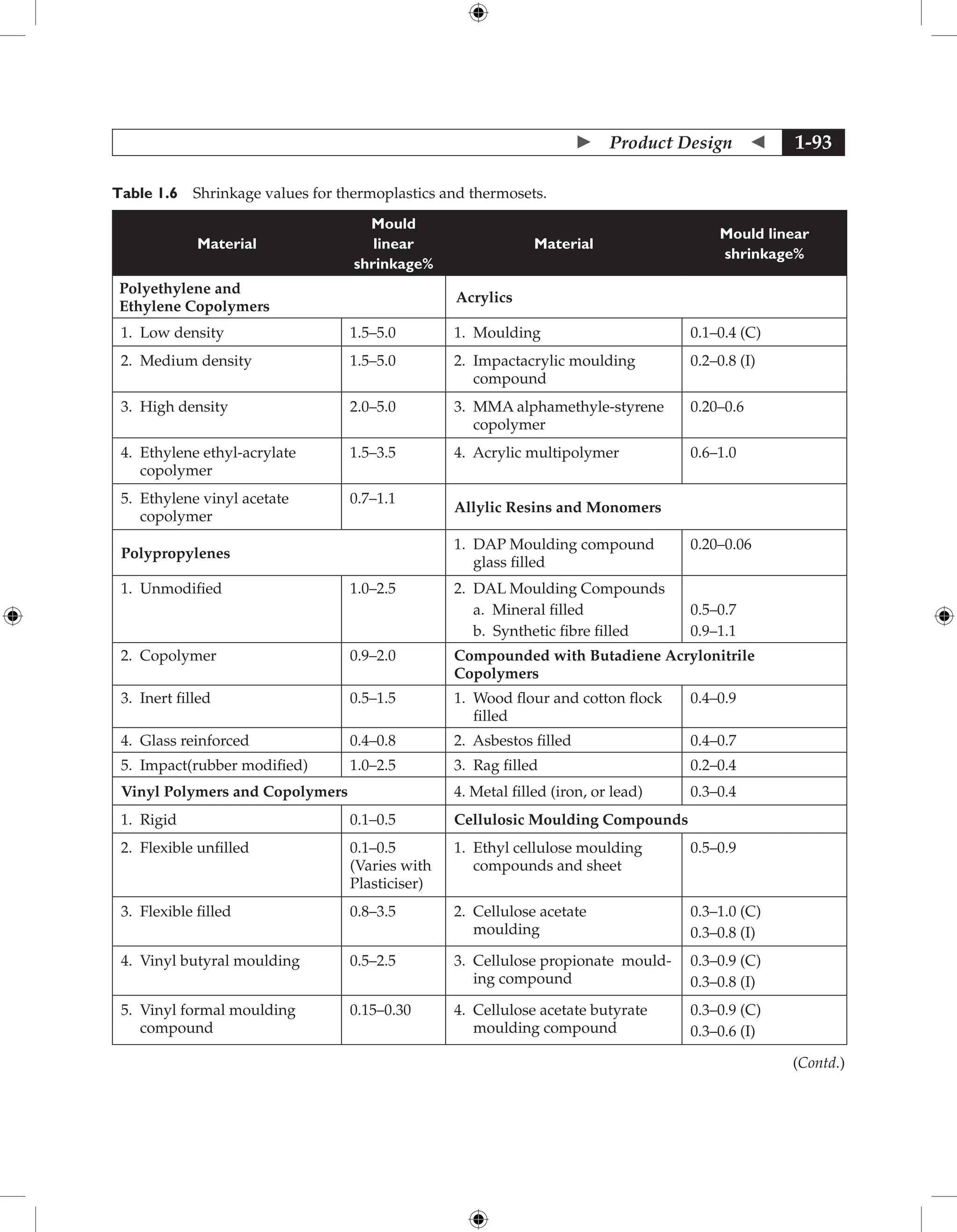

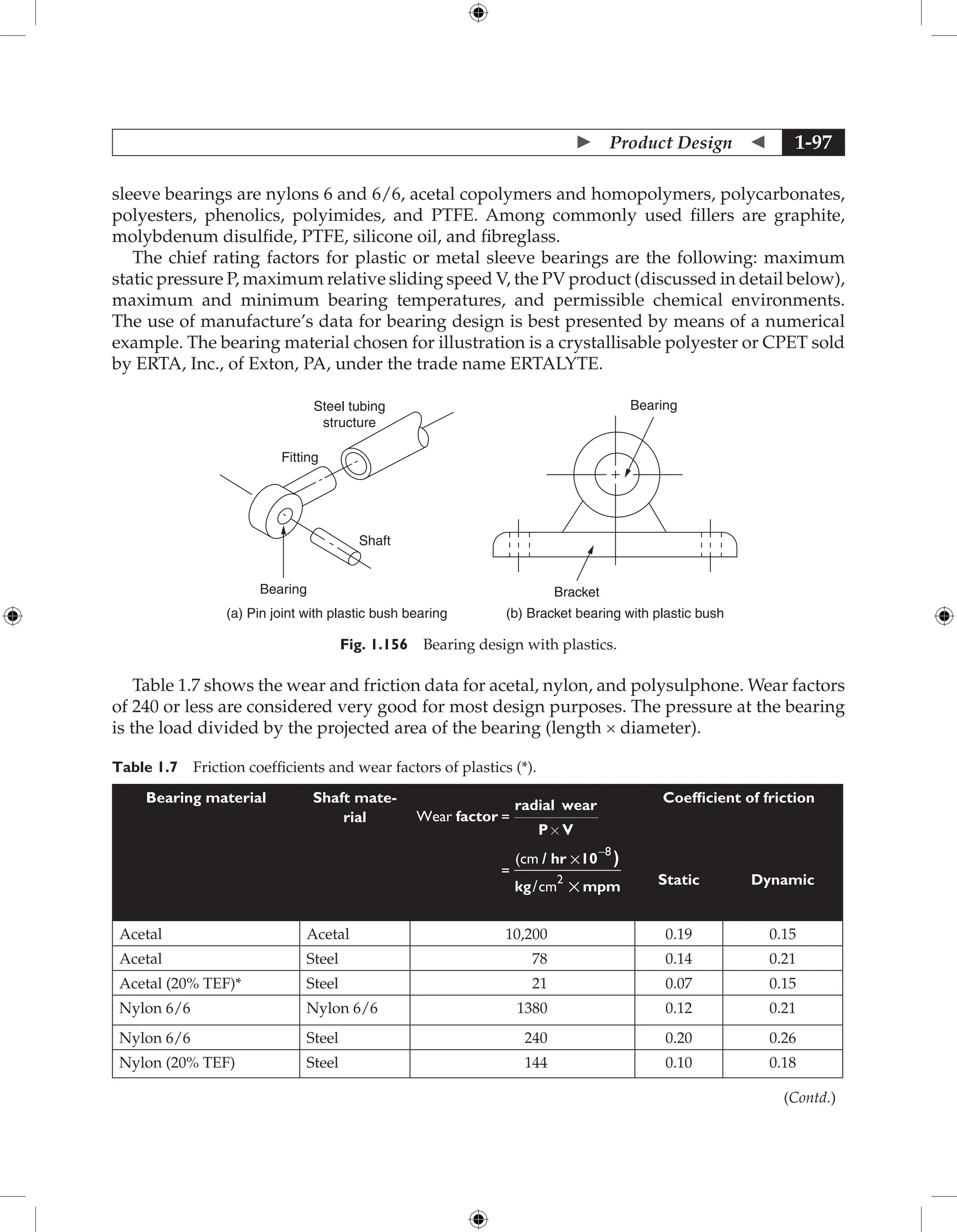

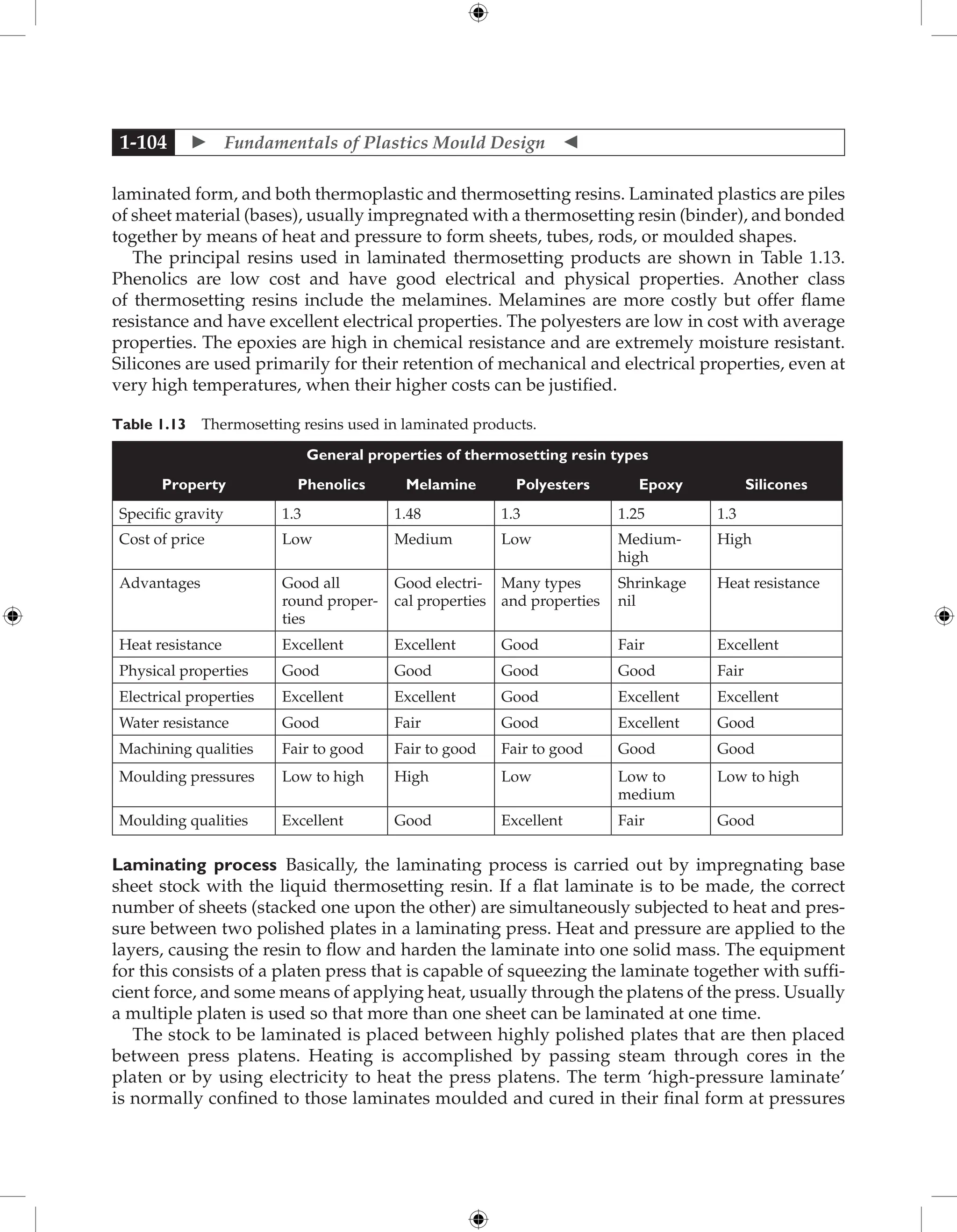

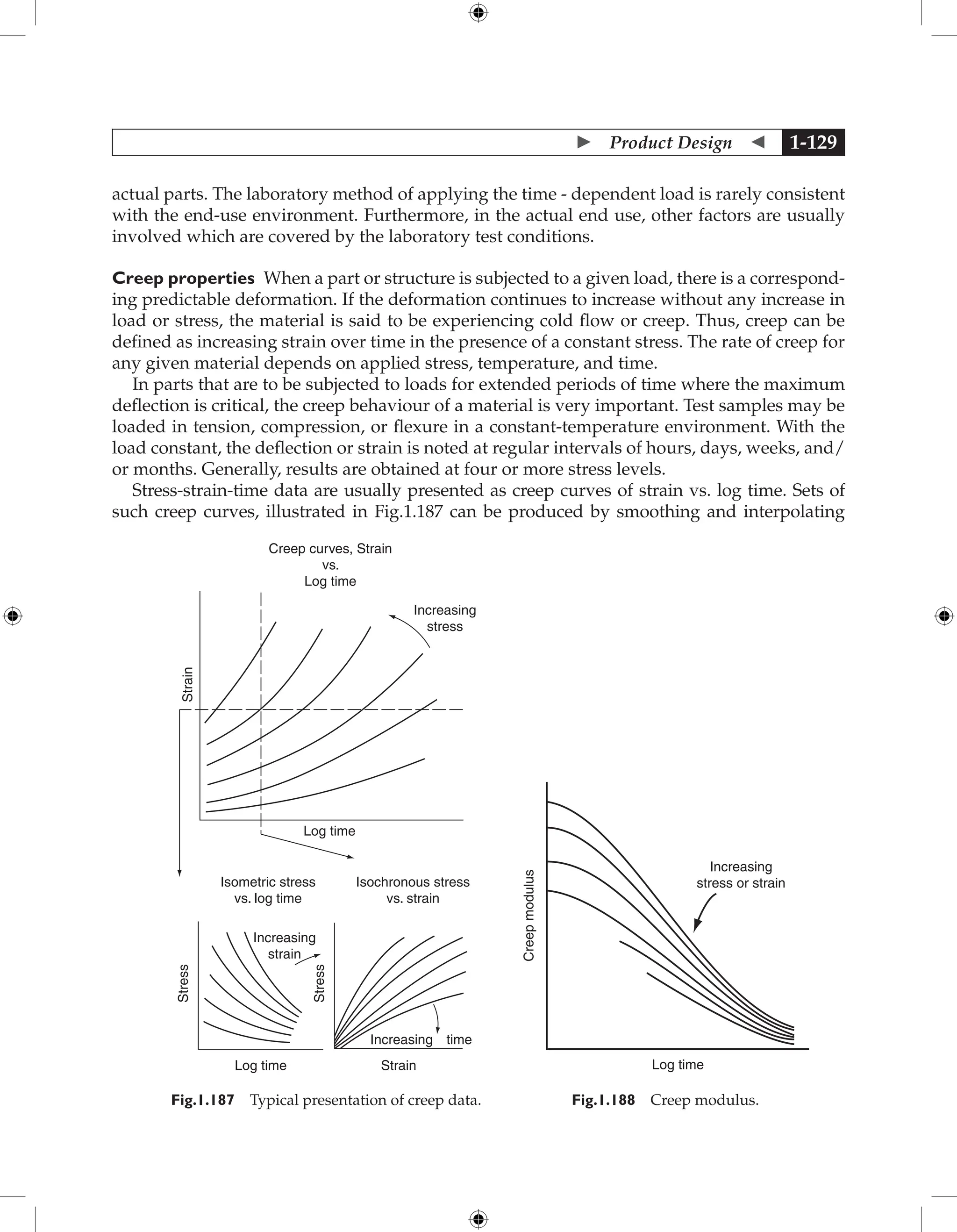

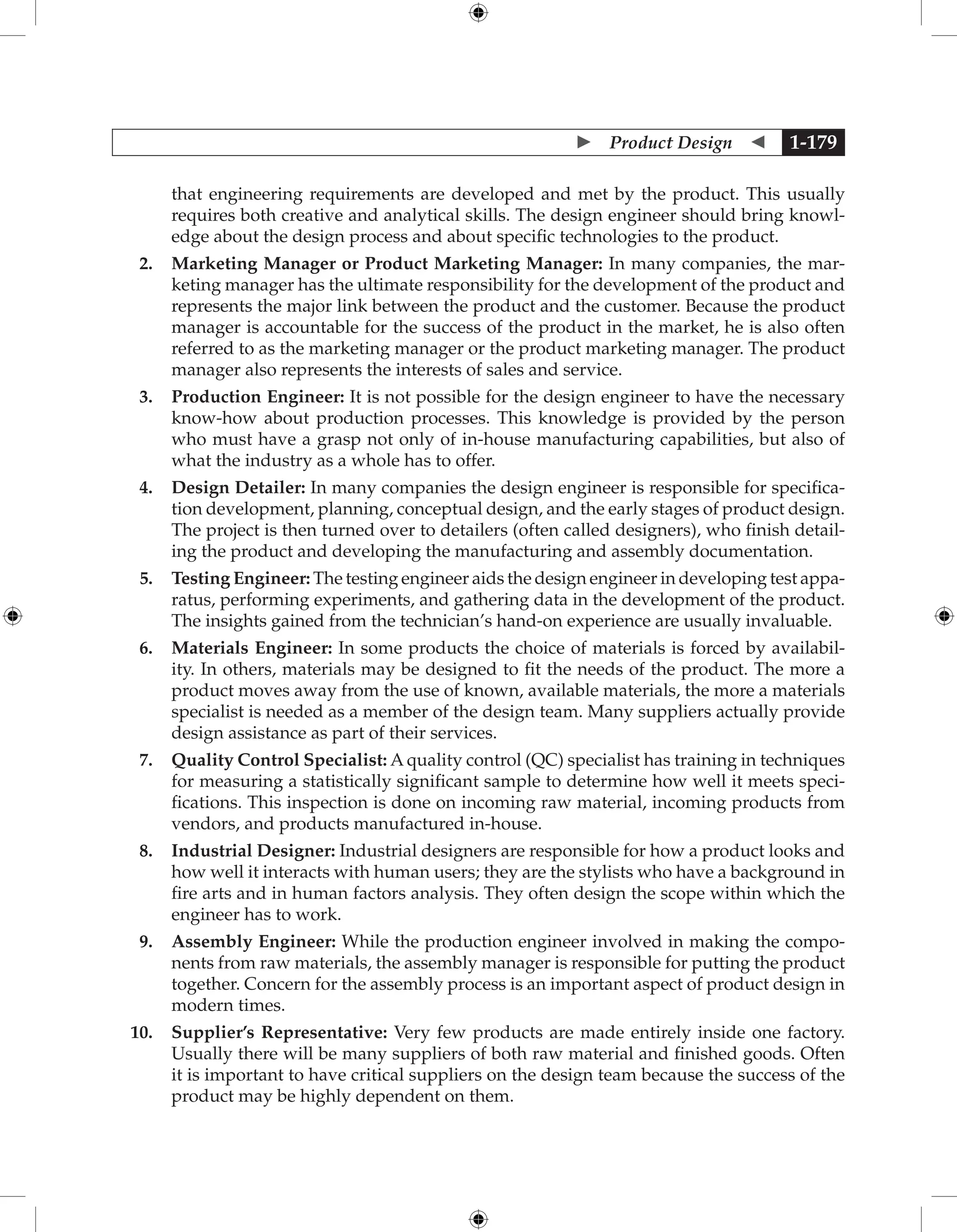

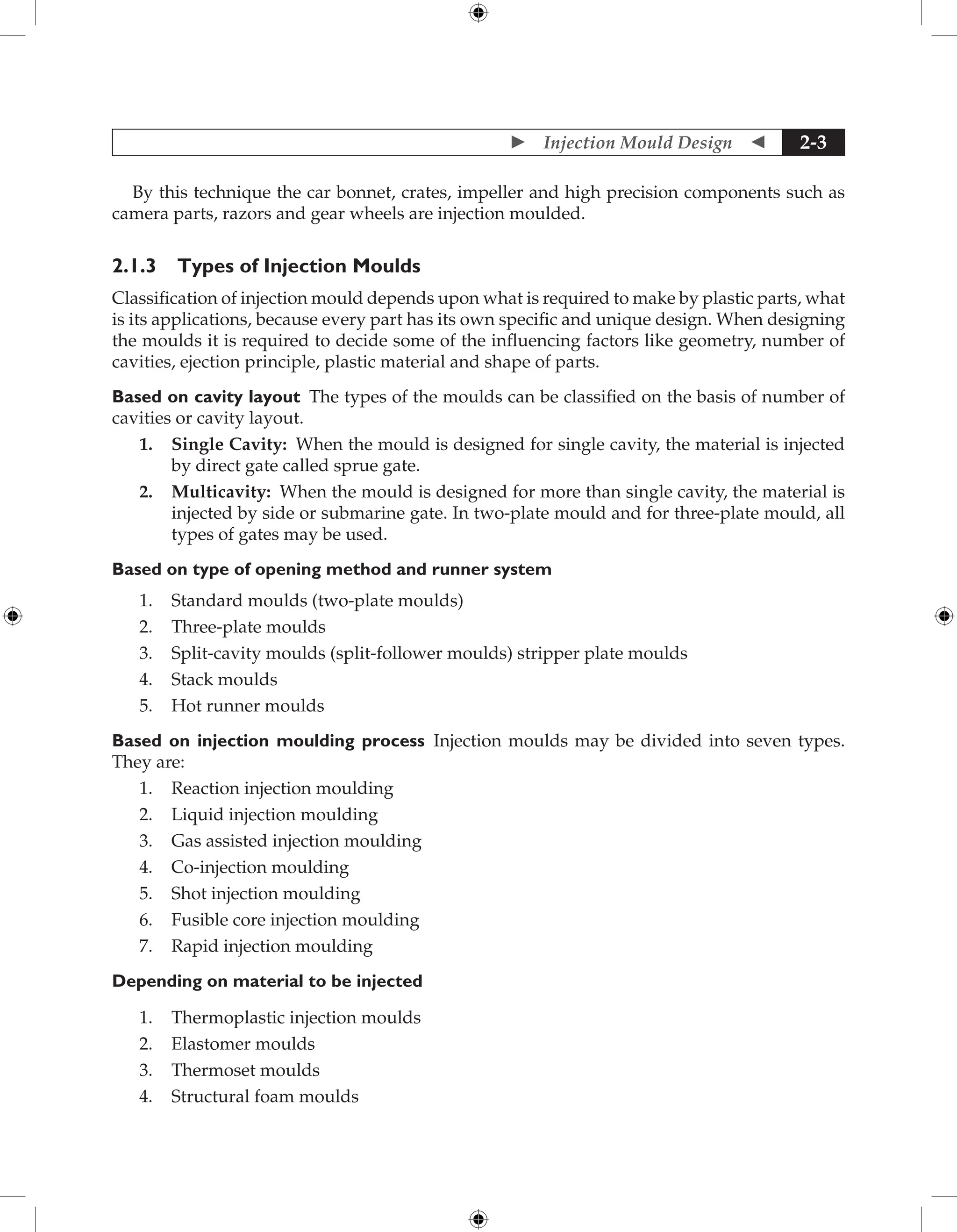

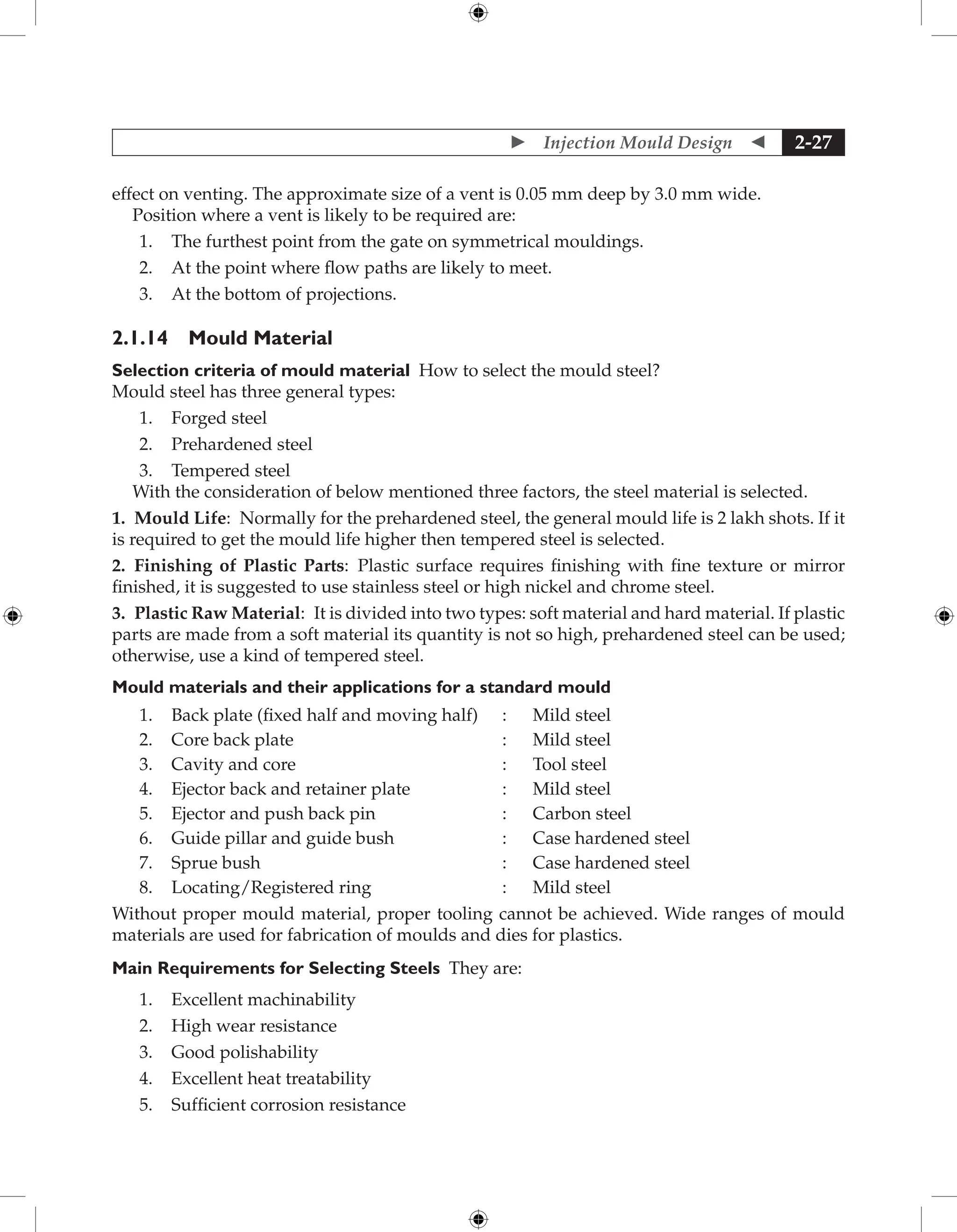

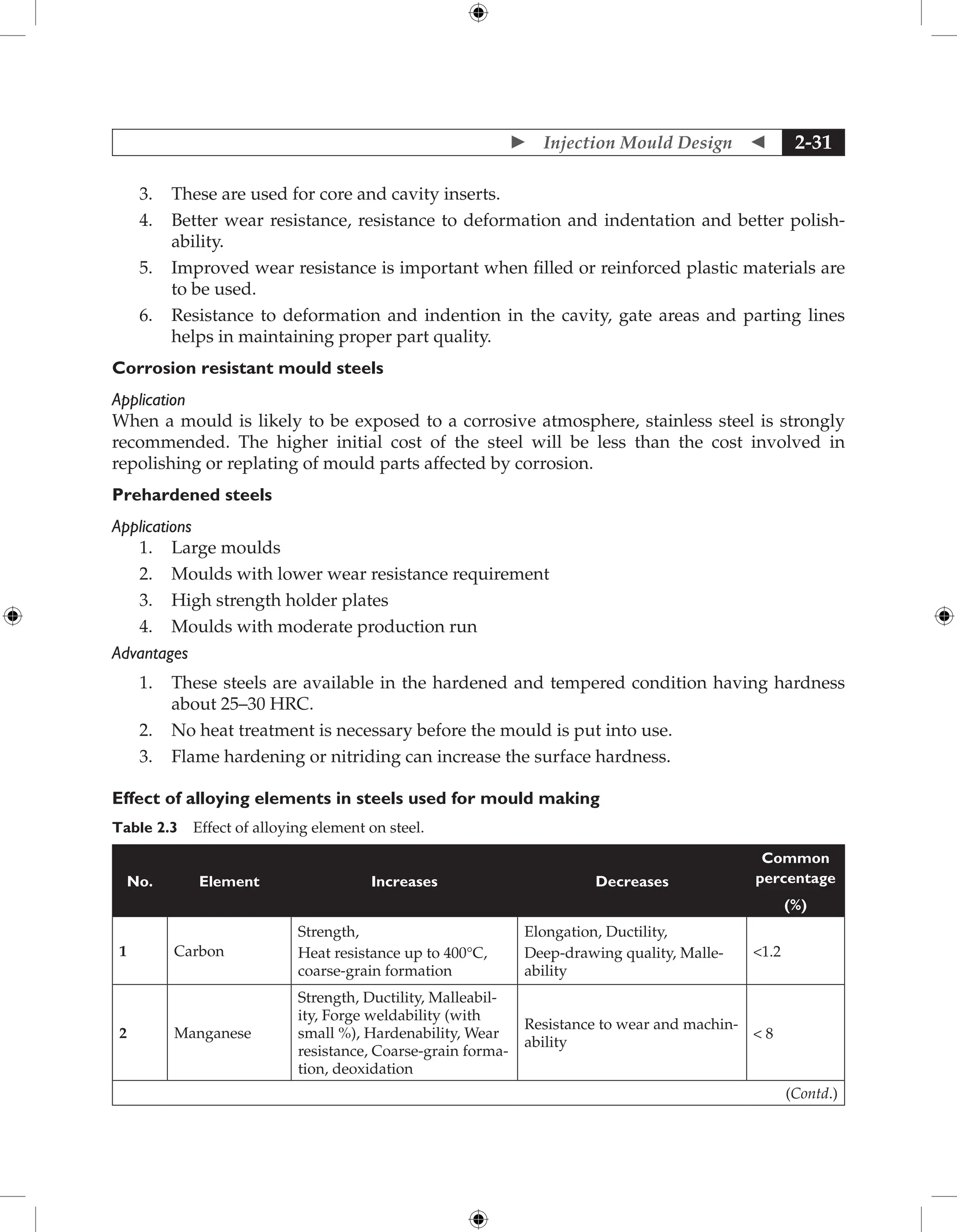

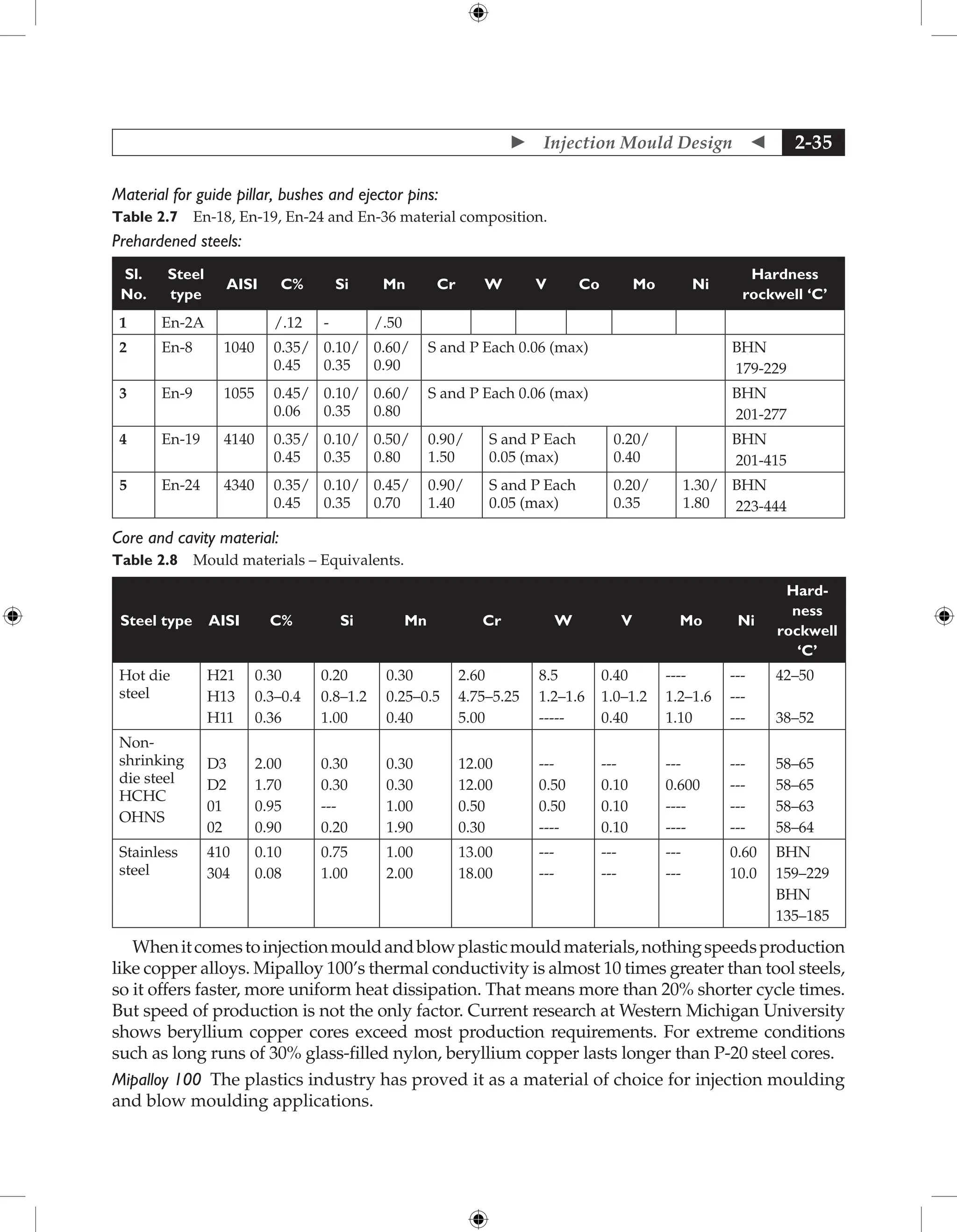

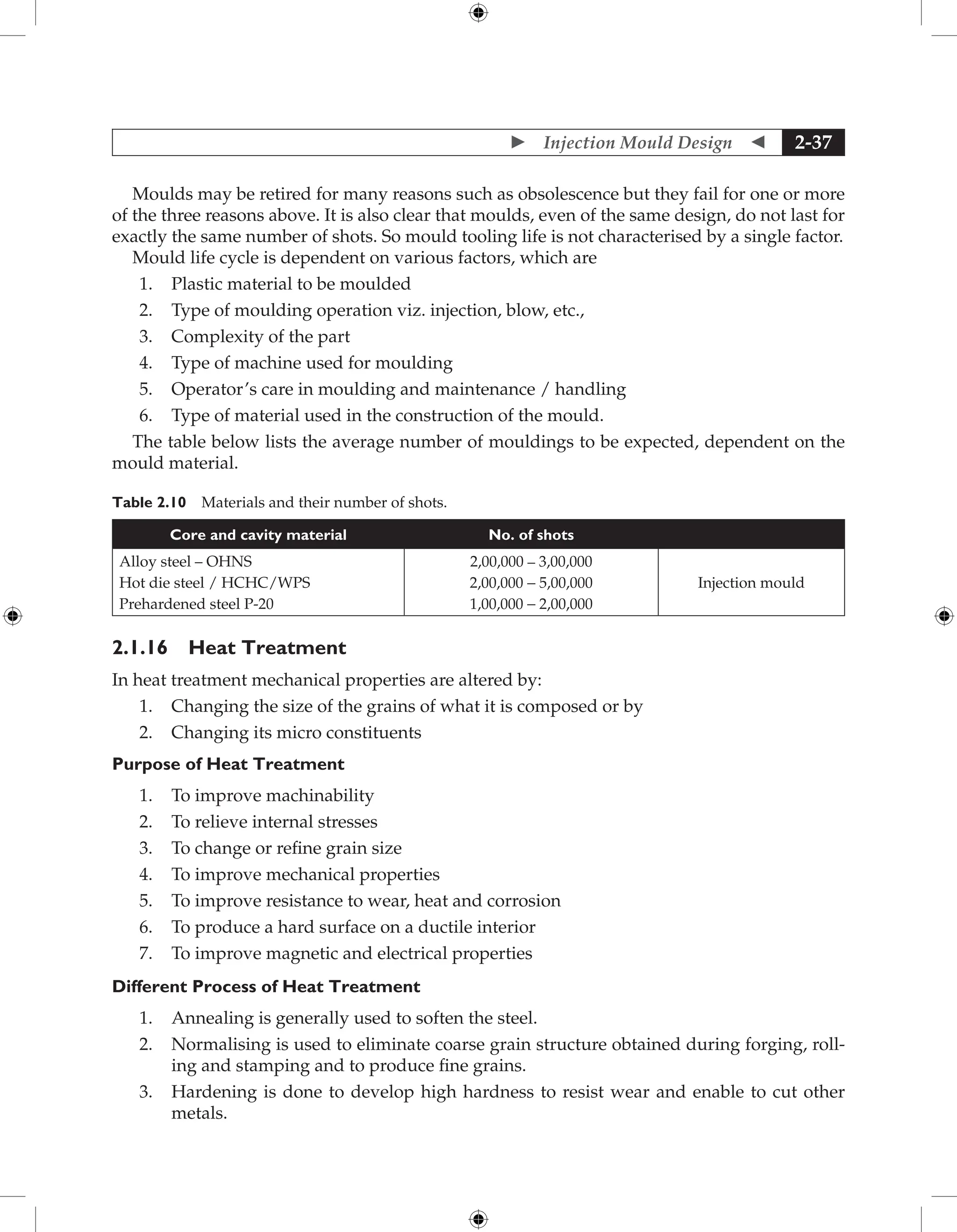

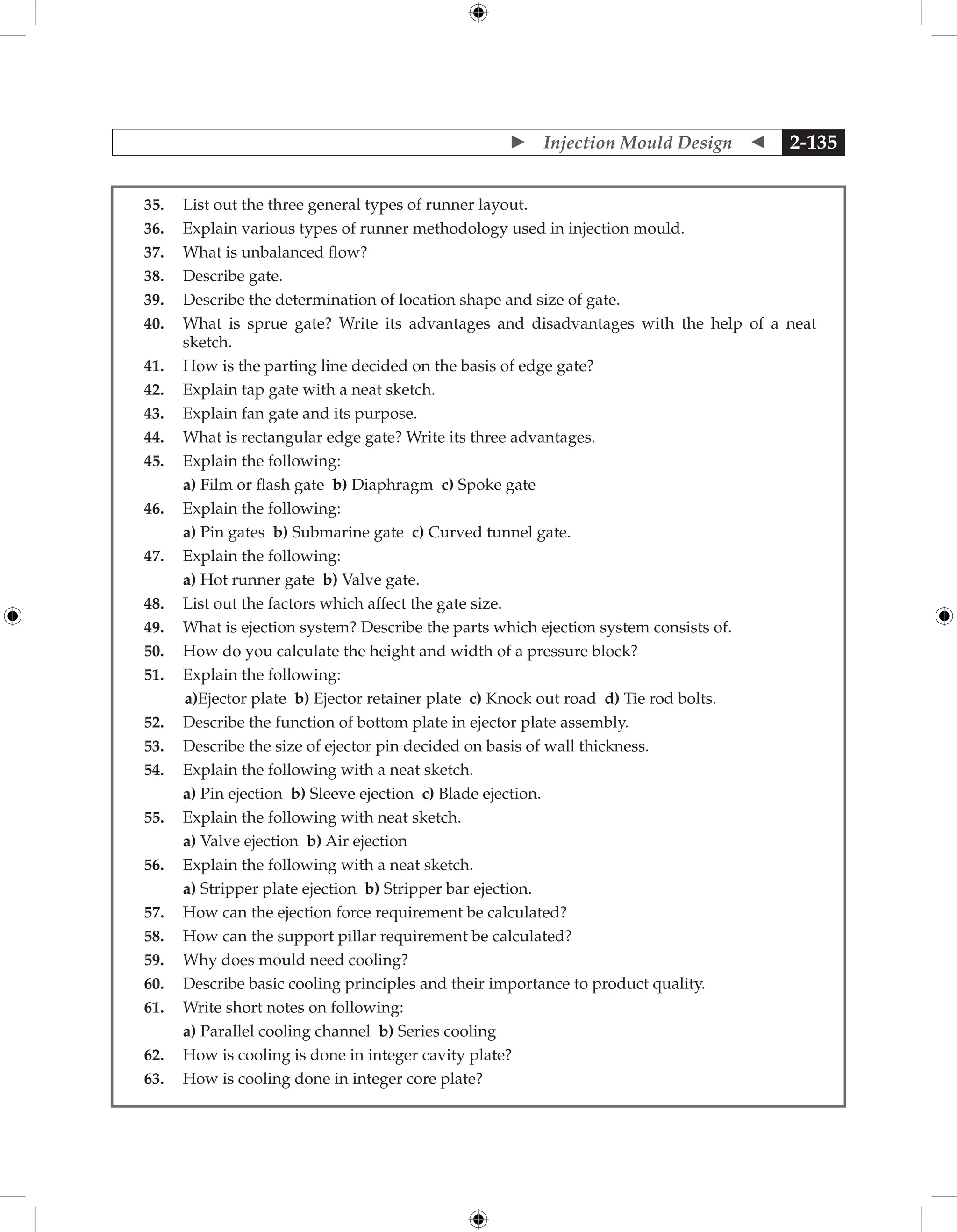

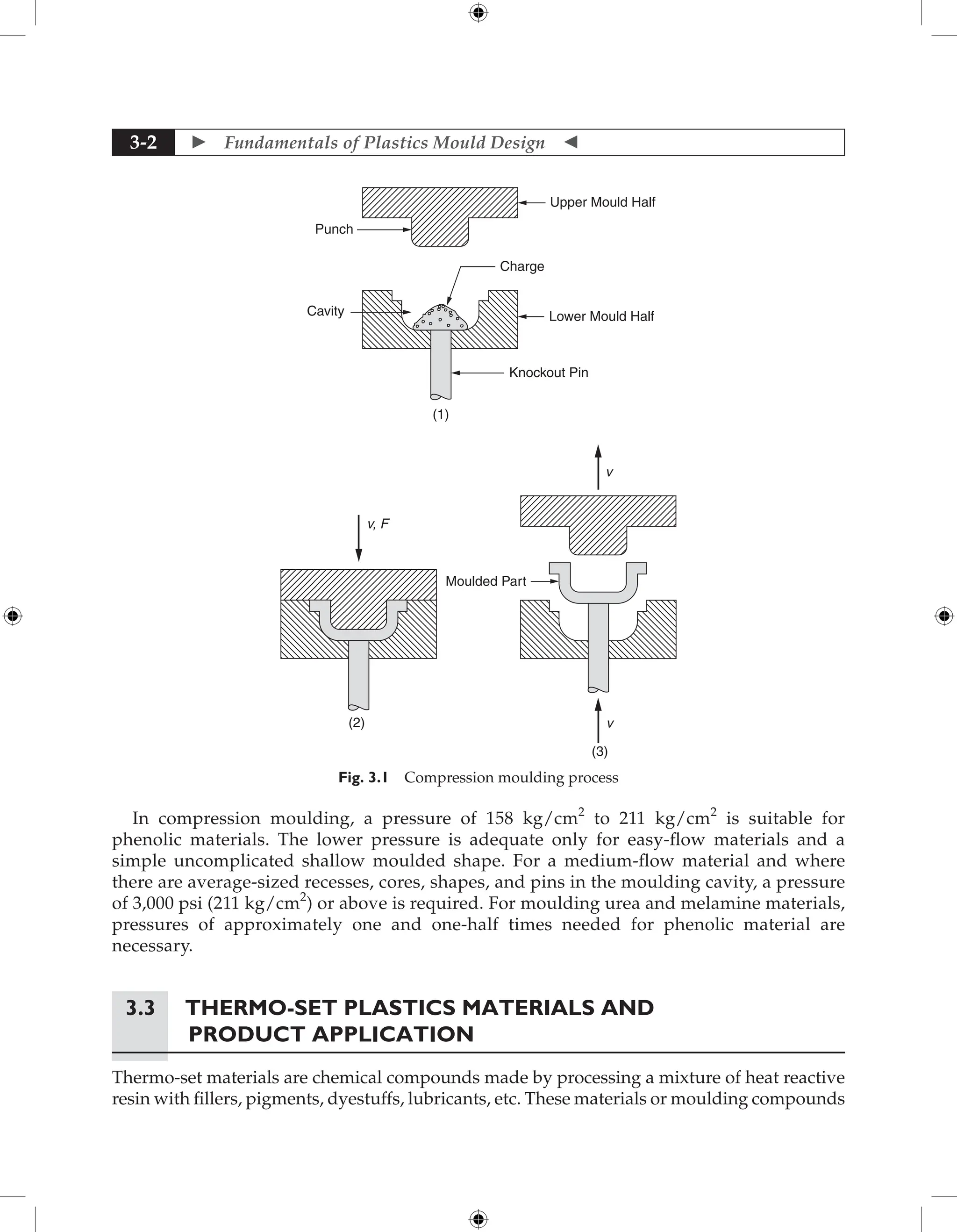

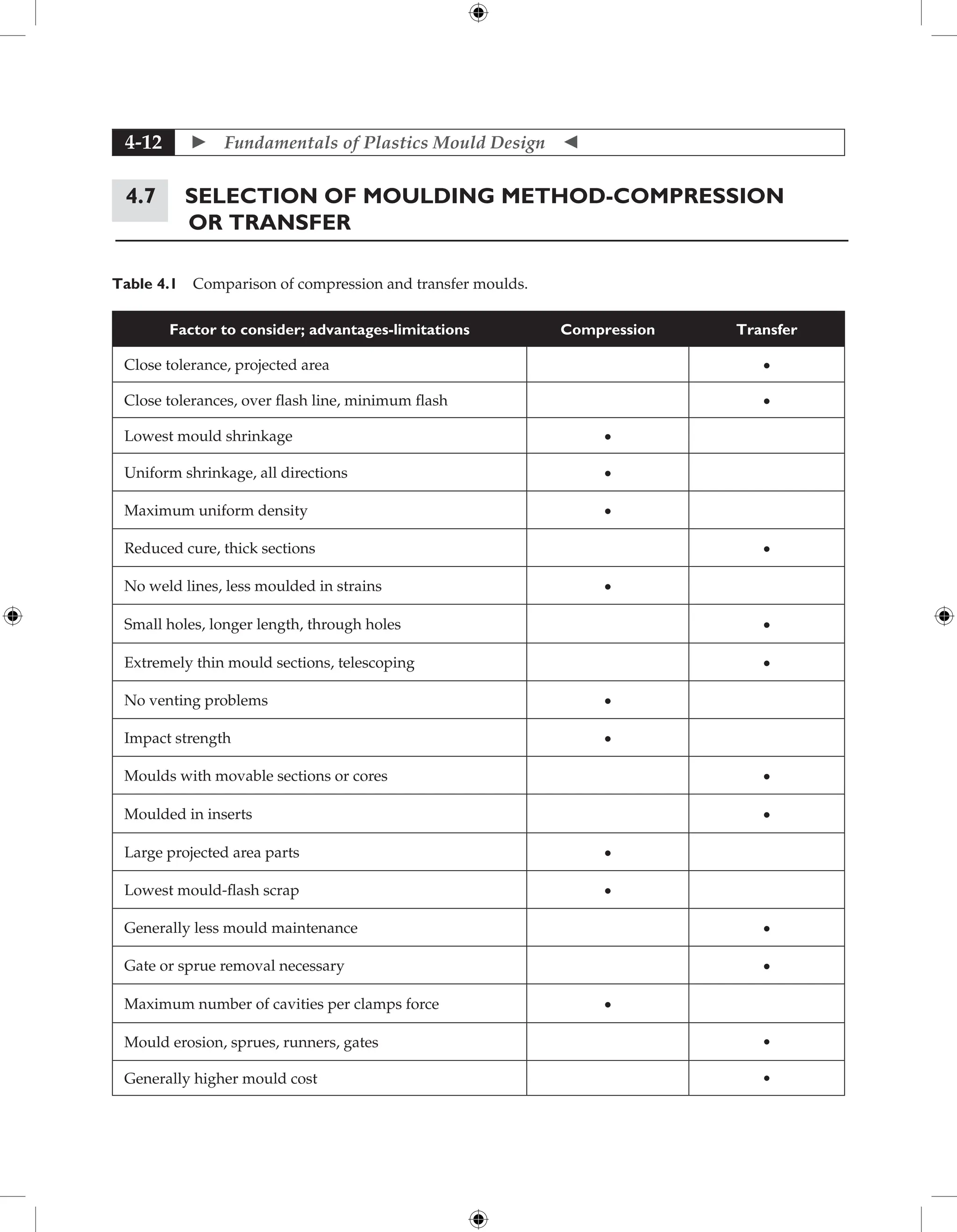

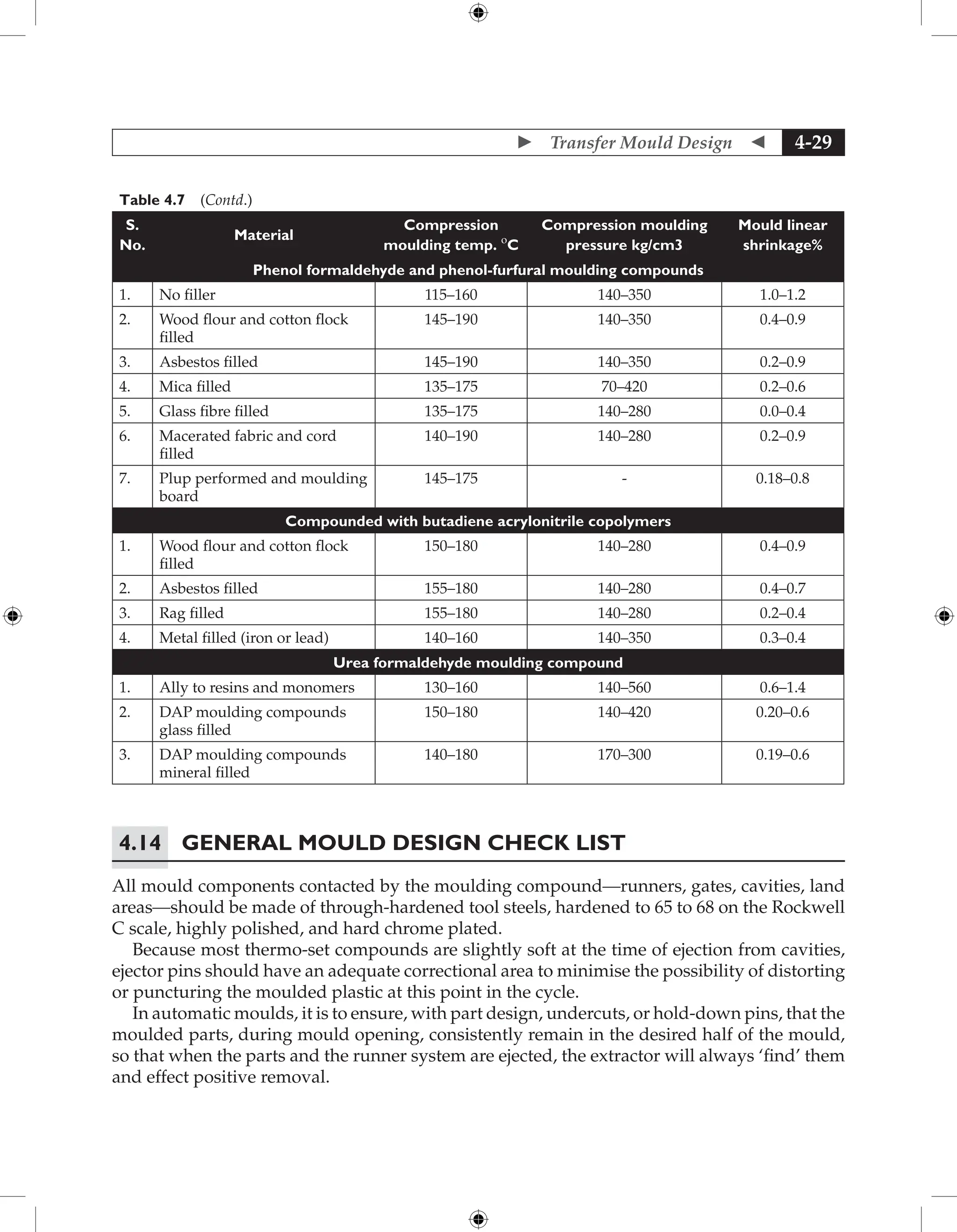

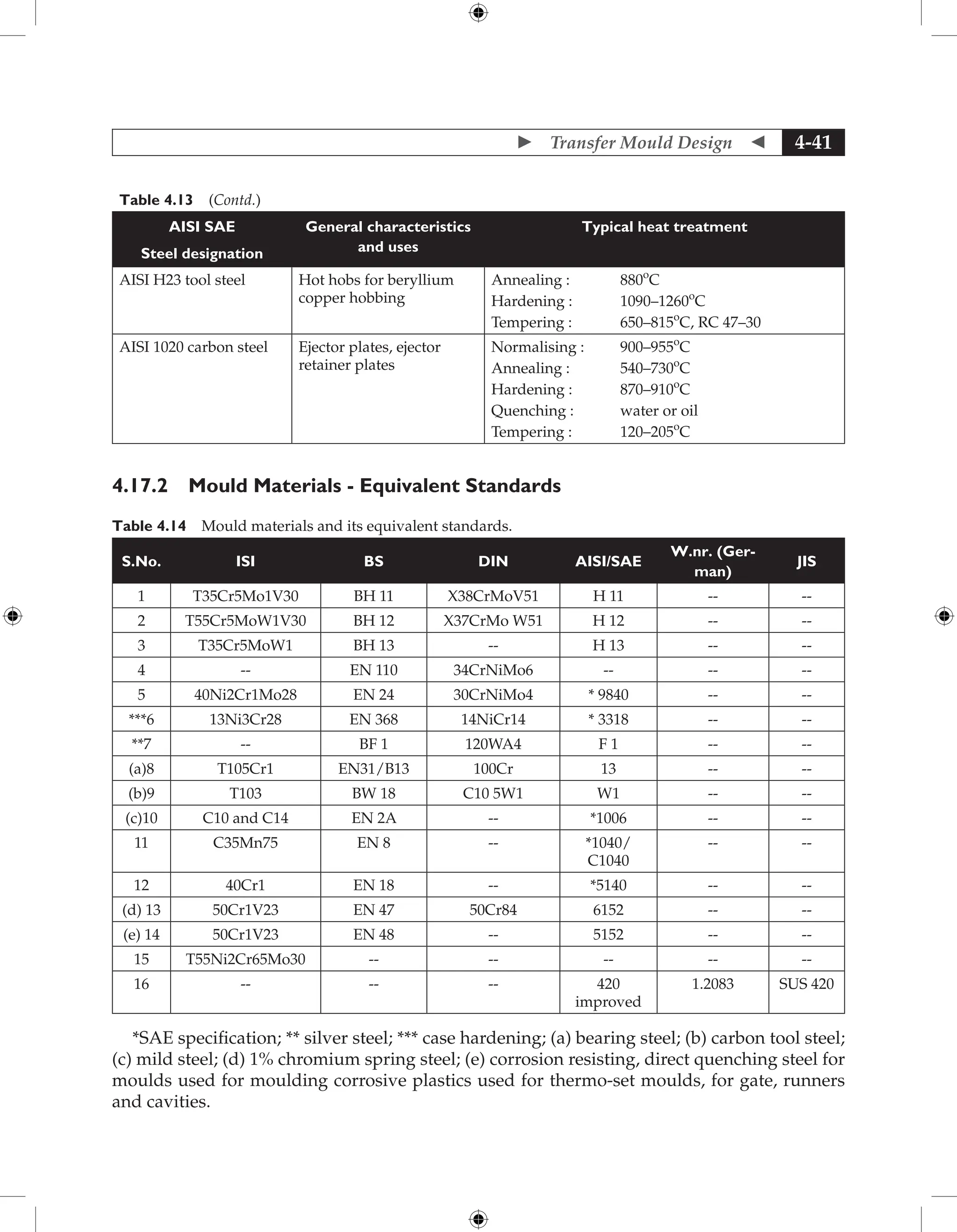

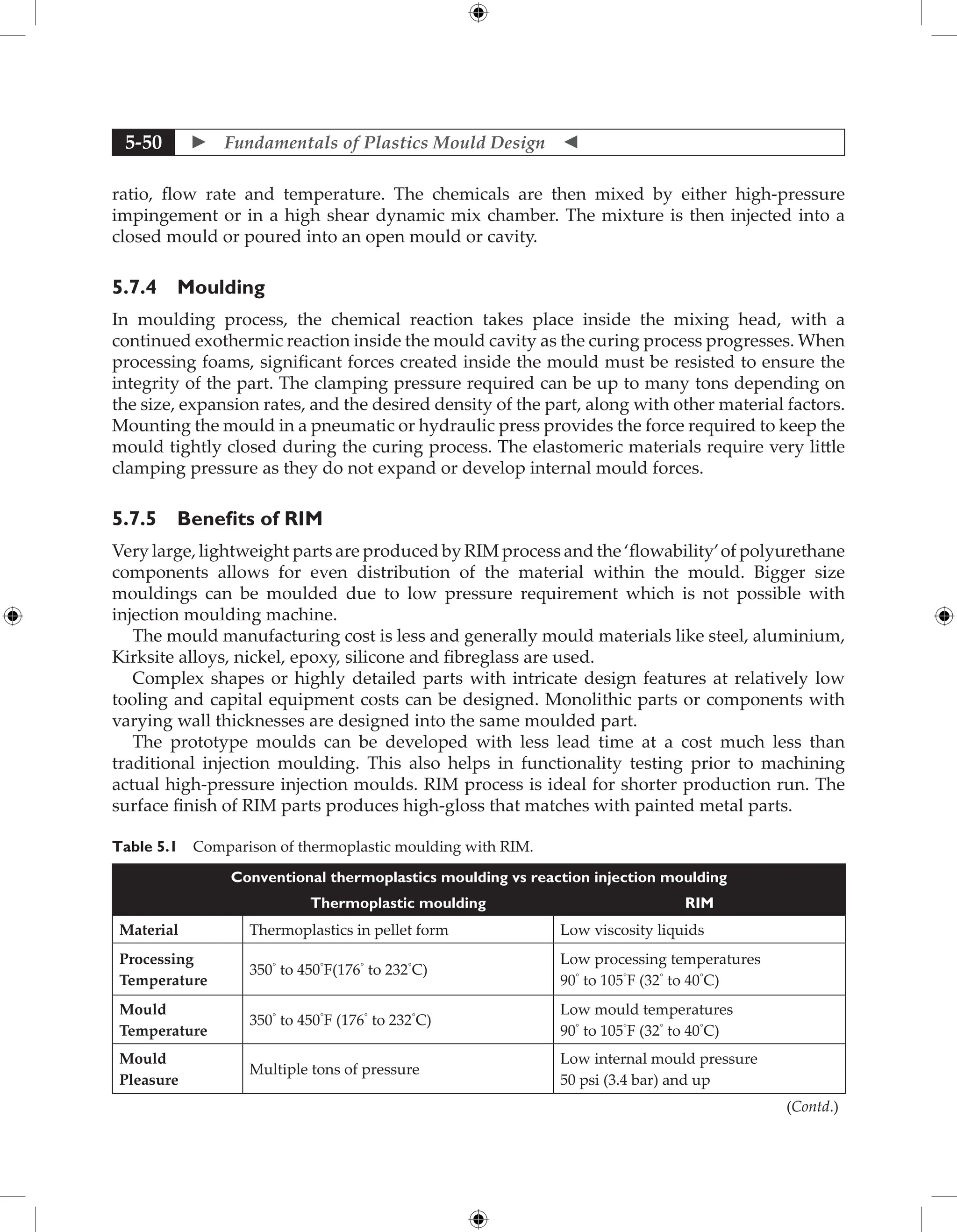

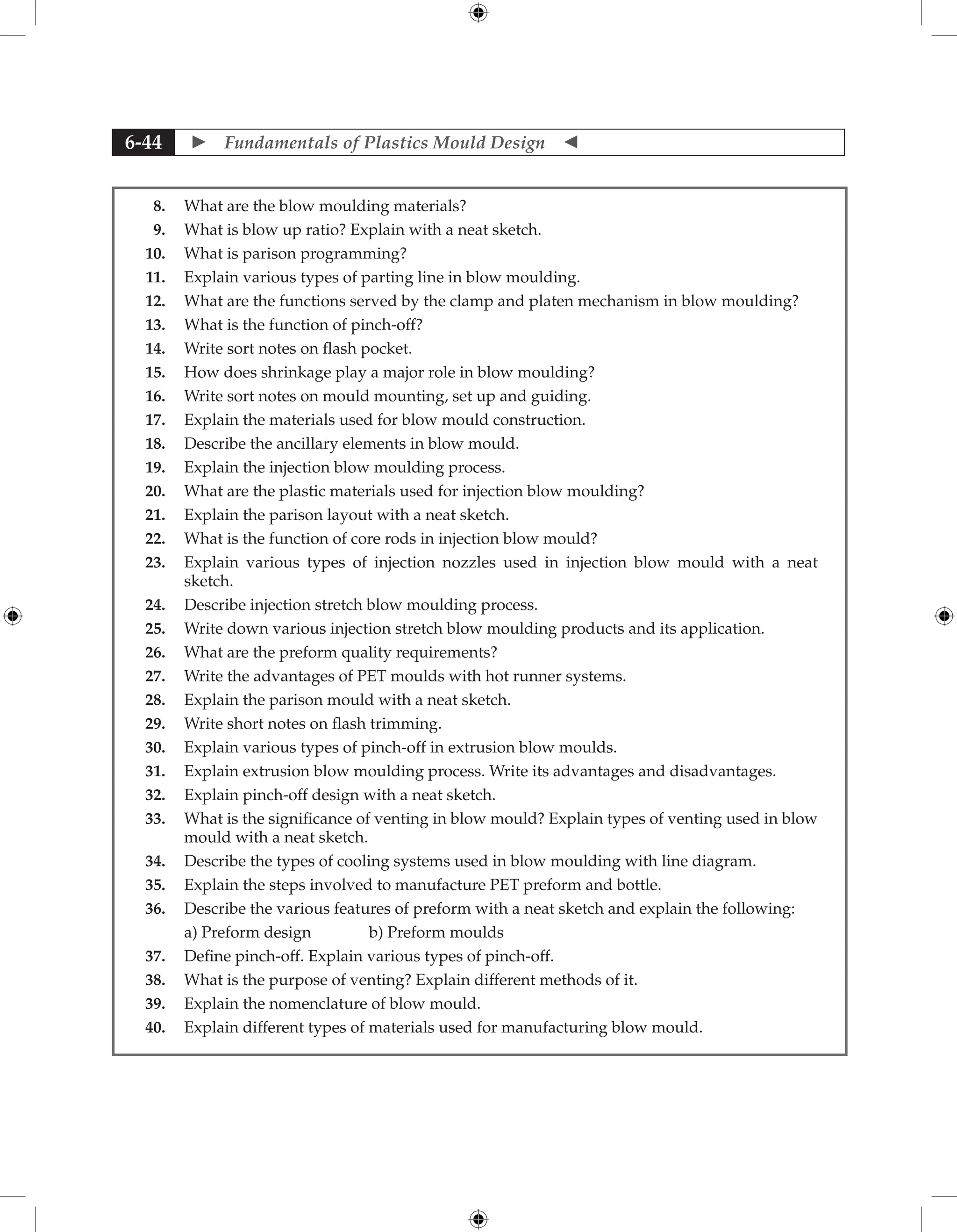

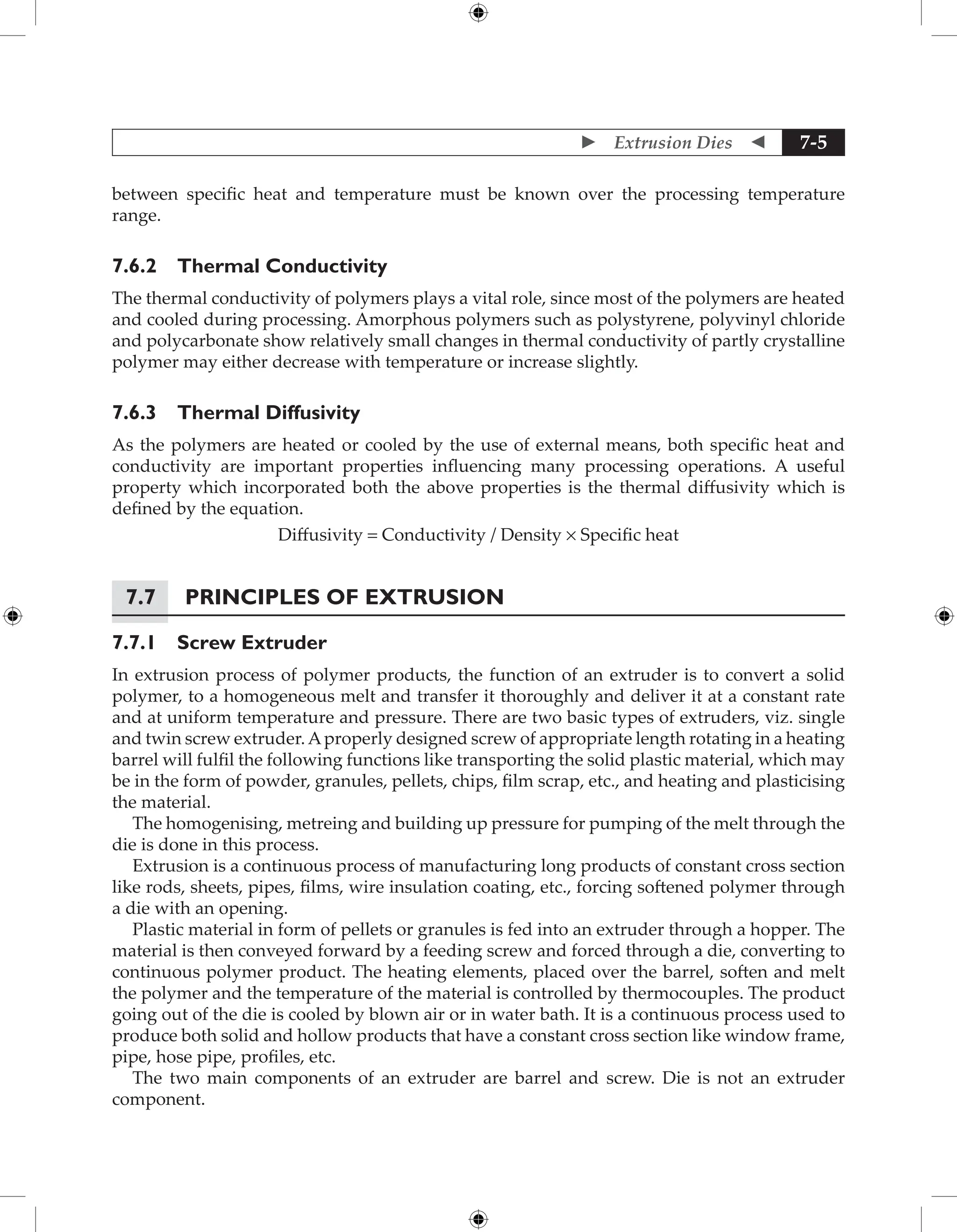

Fig. 2.70 Unbalanced runner system.

2. Balanced Runner of Six Cavities: Although this runner layout is not the best solution but

it is better for six cavities layout as in this layout the fill time is same for all the six cavities as

shown in Fig. 2.71 and flow is better.

[sec]

Fill Time

0

0.11

0.21

0.32

0.42

0.53

0.64

0.74

0.85

0.96

1.06

126

161

−159

Z

Y

X

20 mm

4

5

6

3

2

1

Fig. 2.71 Filling time result.

Runner system an effective part of the system Since the design of the runner system has

large effect on moulding quality, moulding efficiency, cycle time, cooling time and other factor,

so it is important factor of the mould.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fundamentalsofmoulddesign-231217032858-869d3d7e/75/Fundamentals-of-Mould-Design-lecture-pdf-251-2048.jpg)

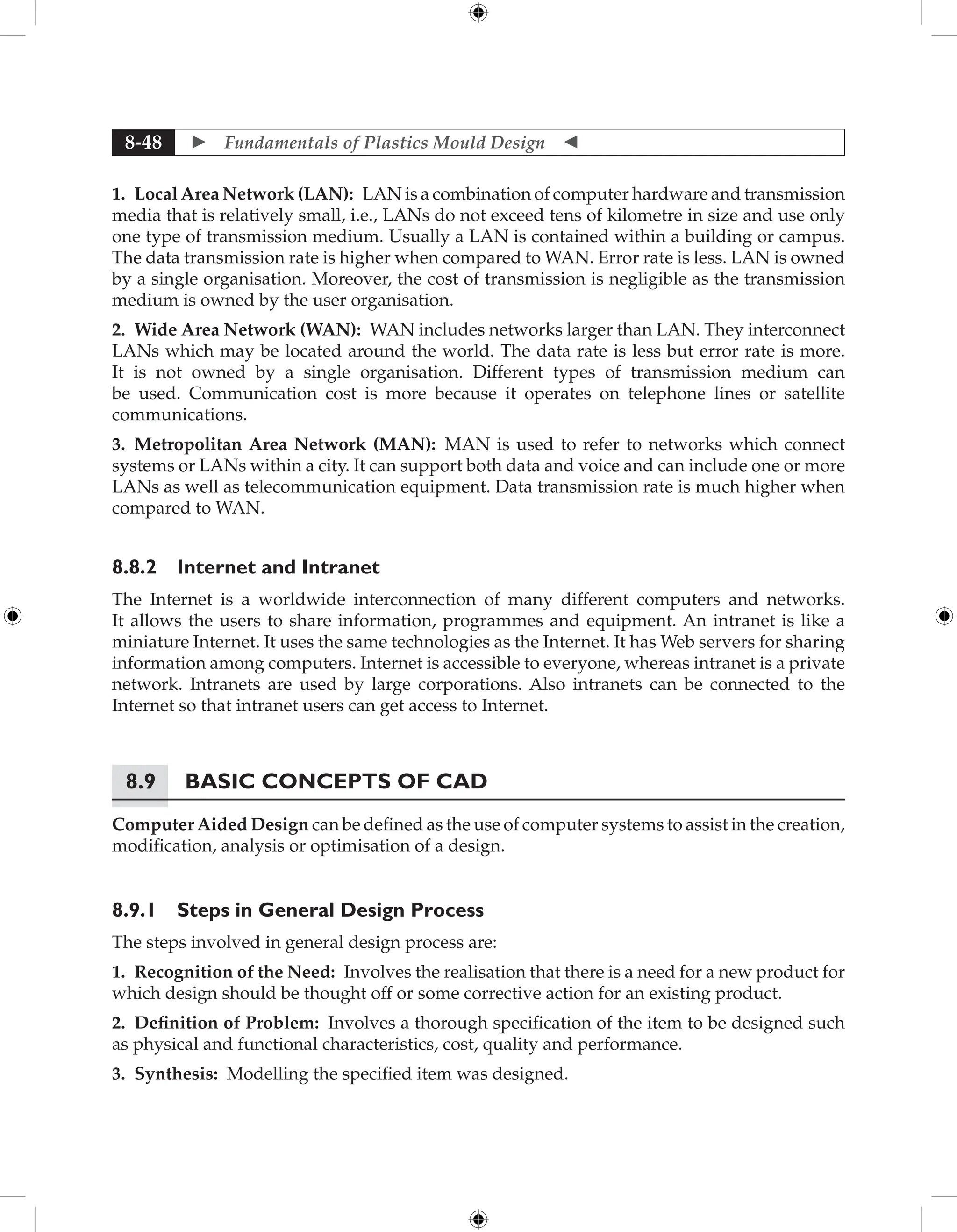

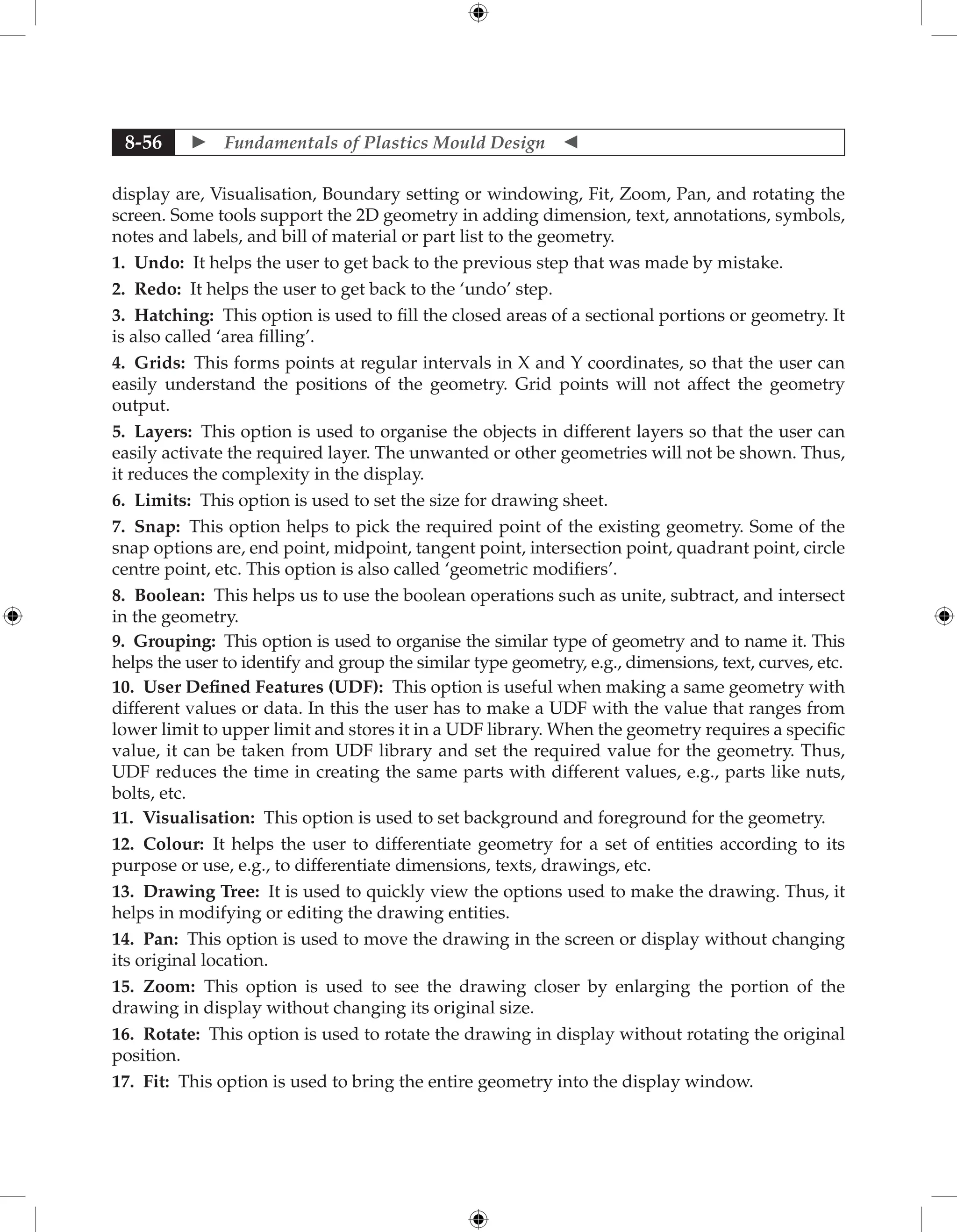

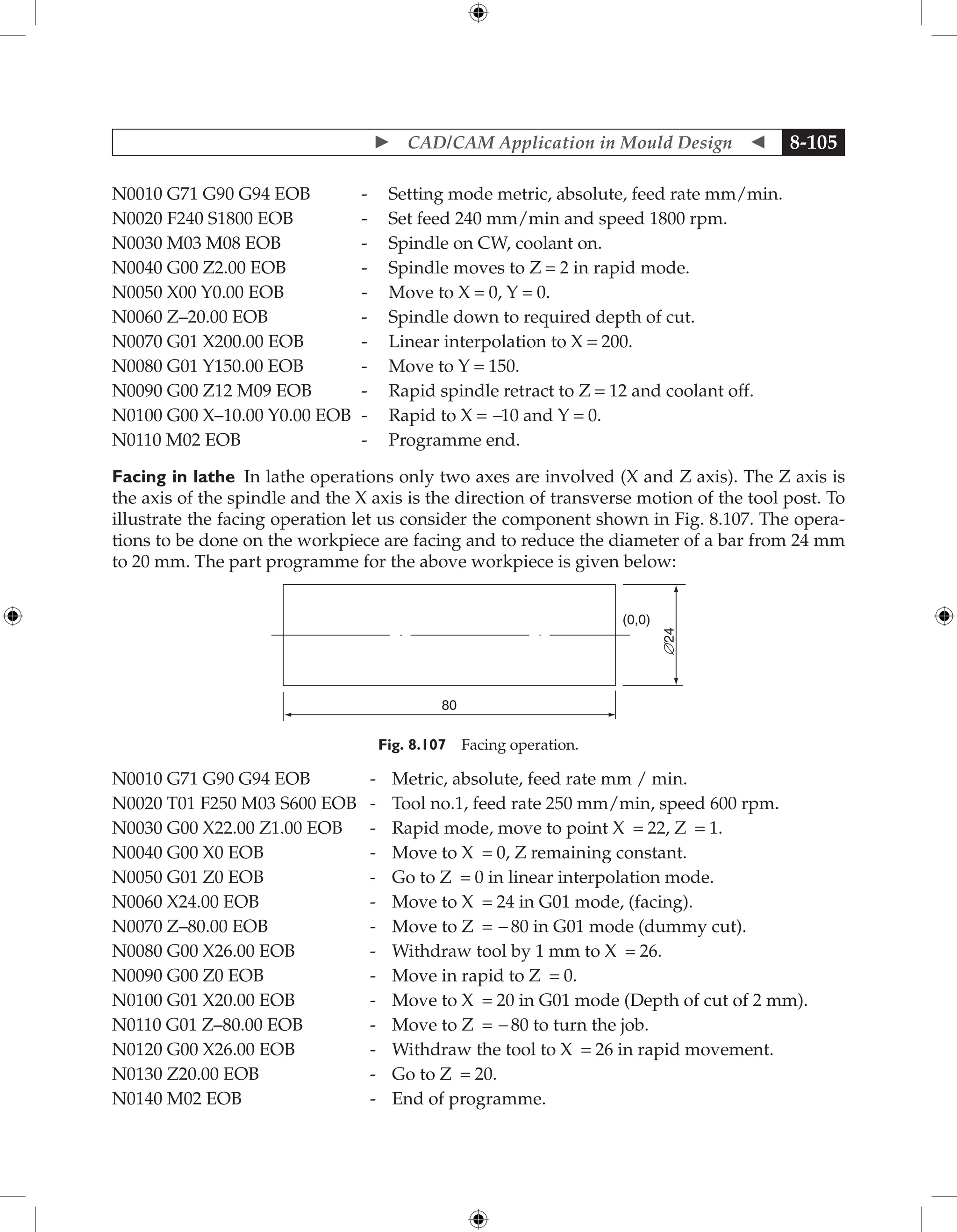

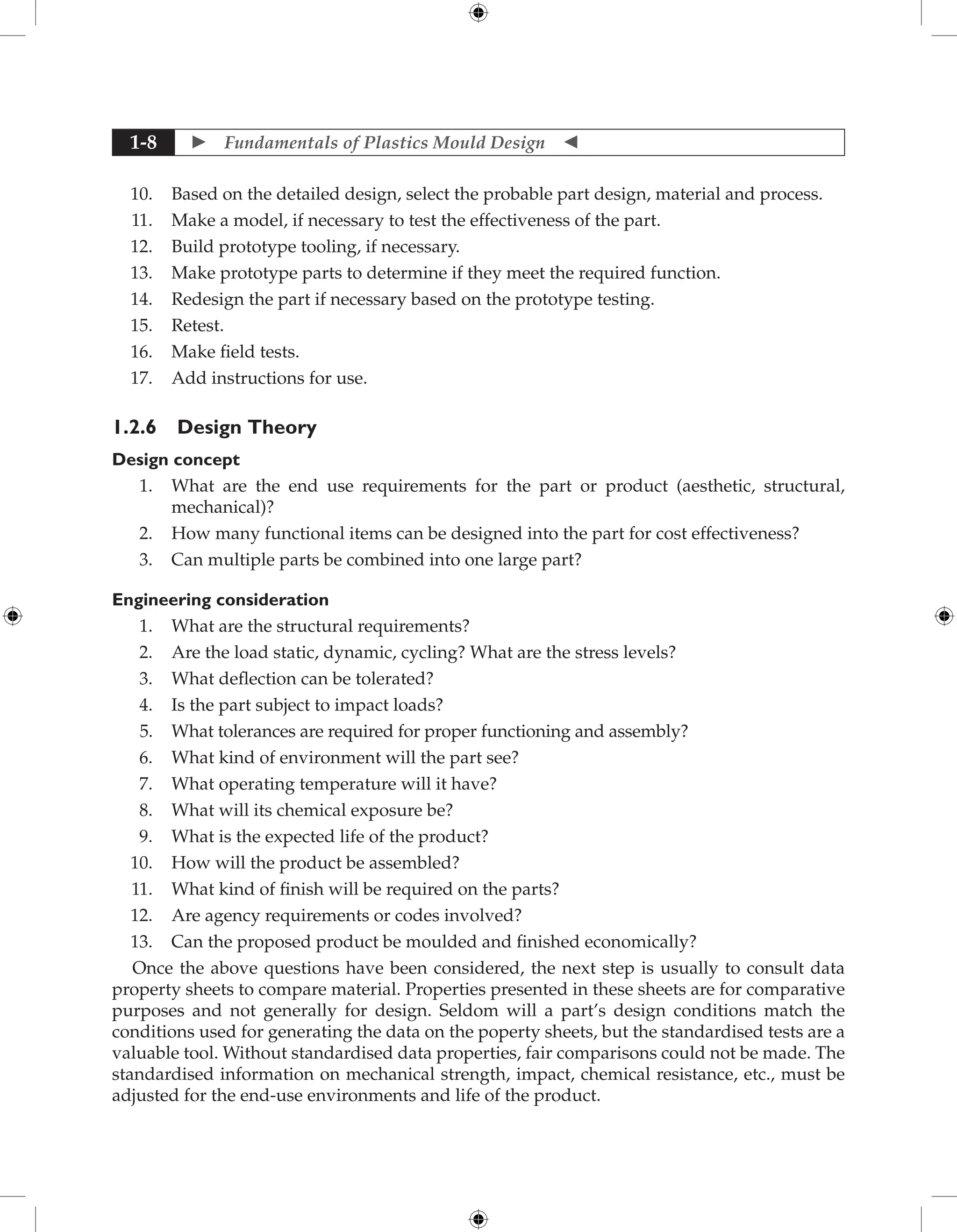

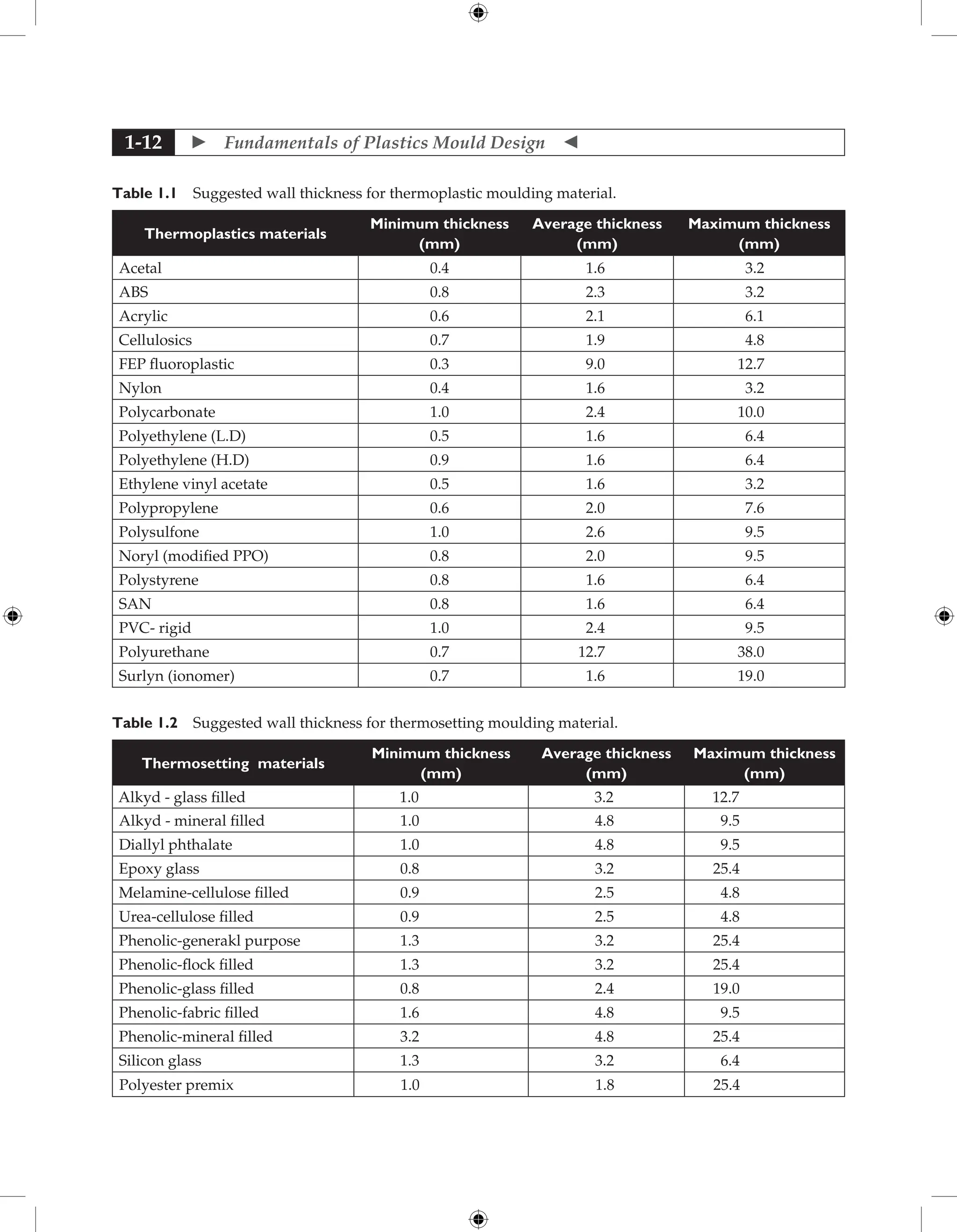

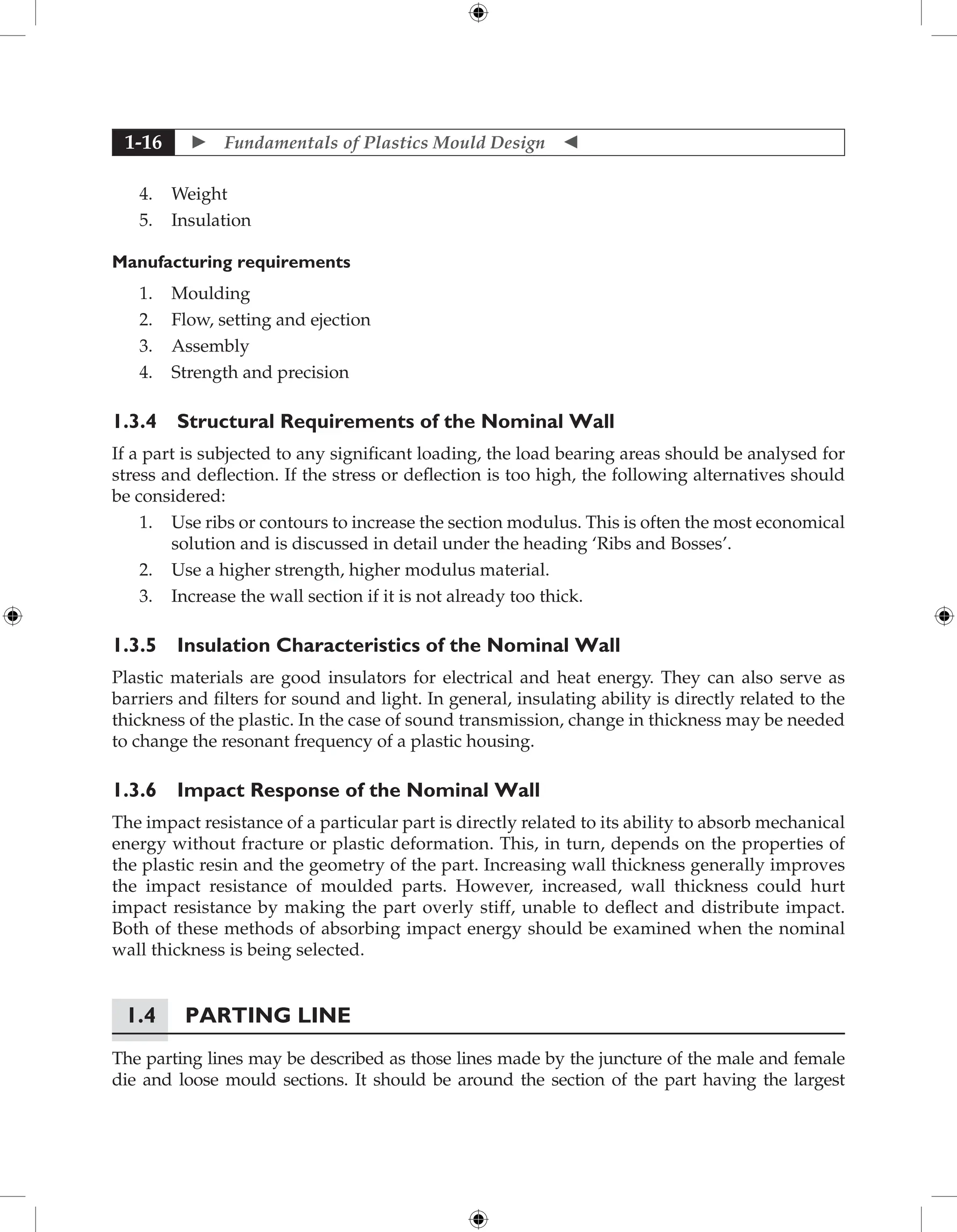

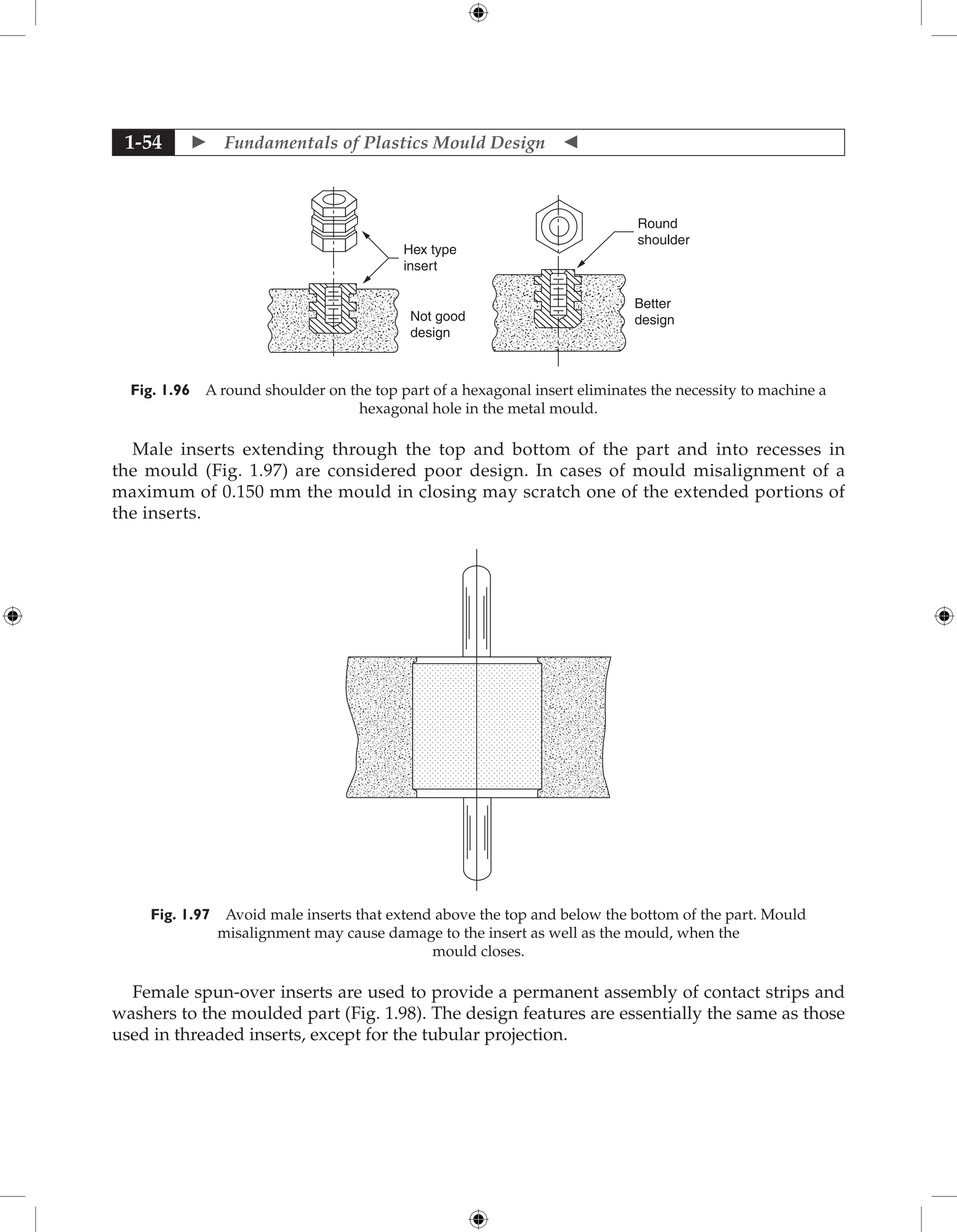

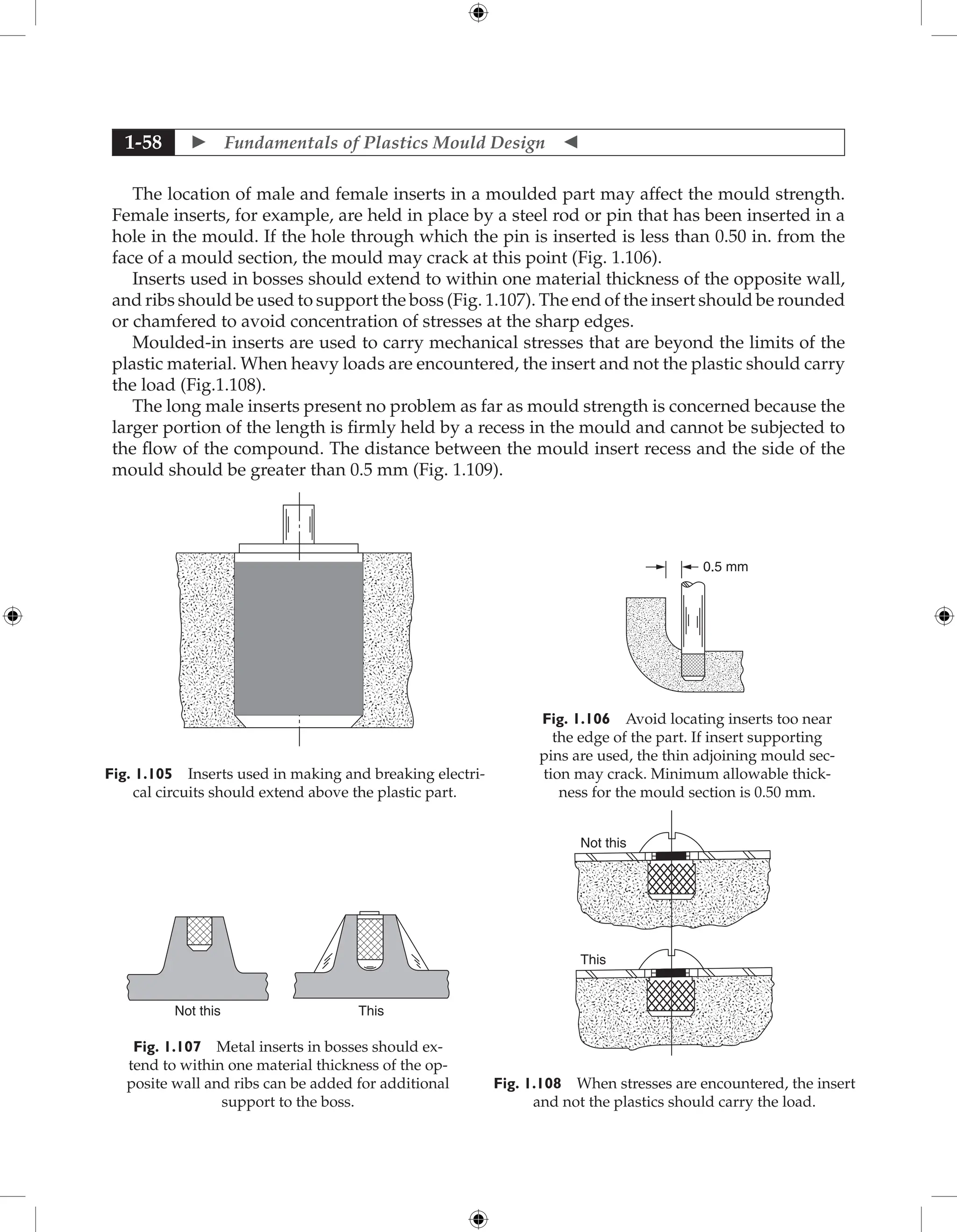

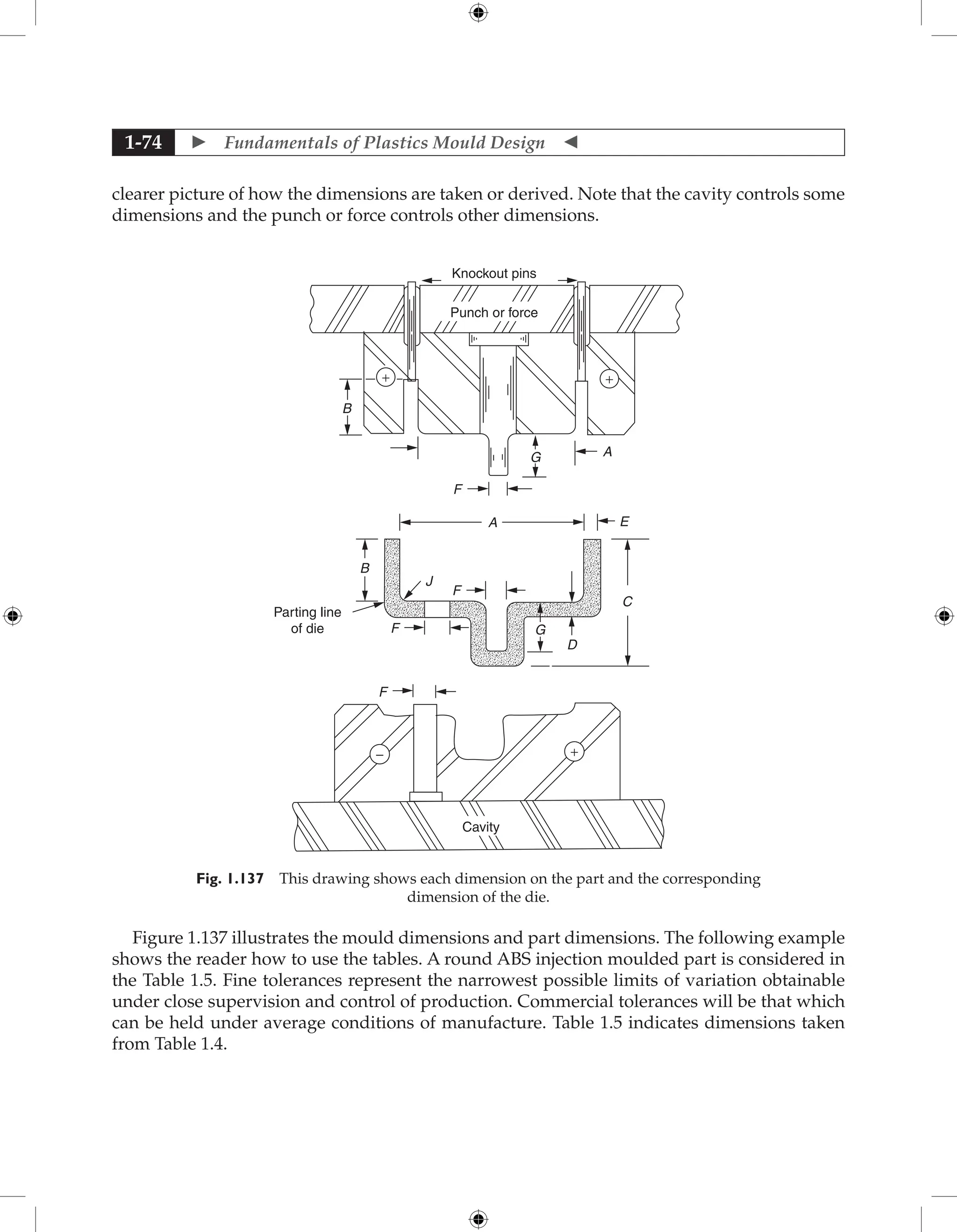

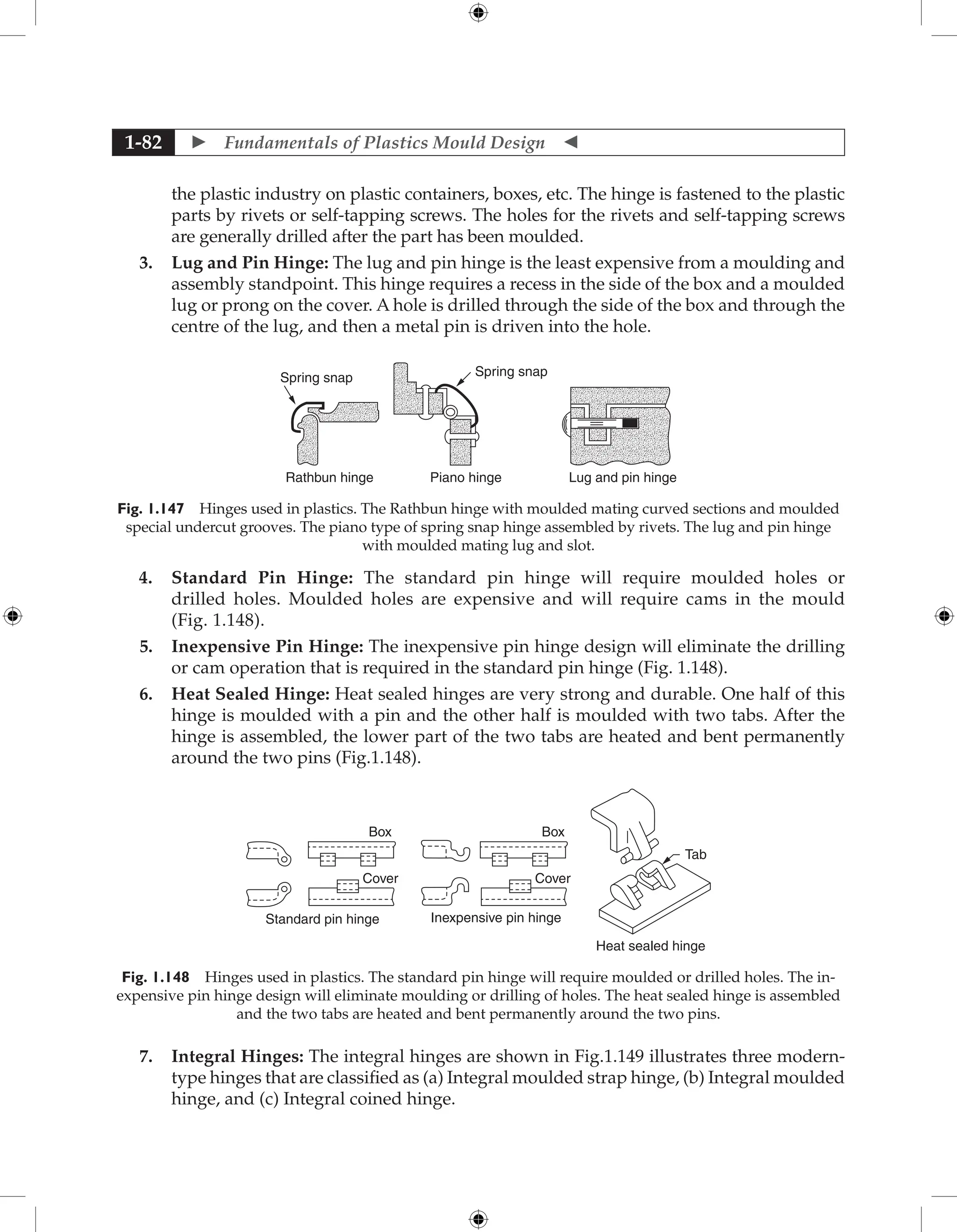

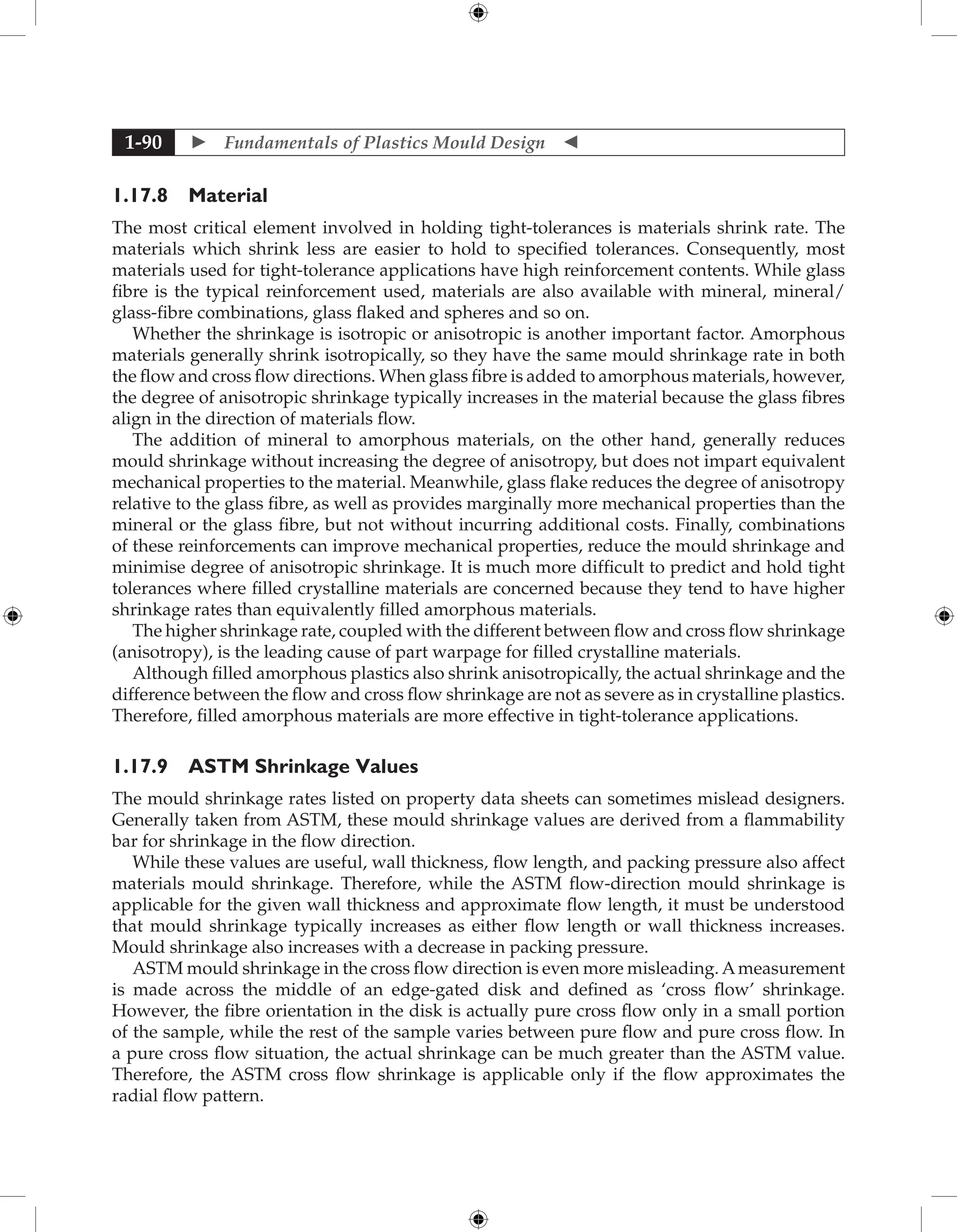

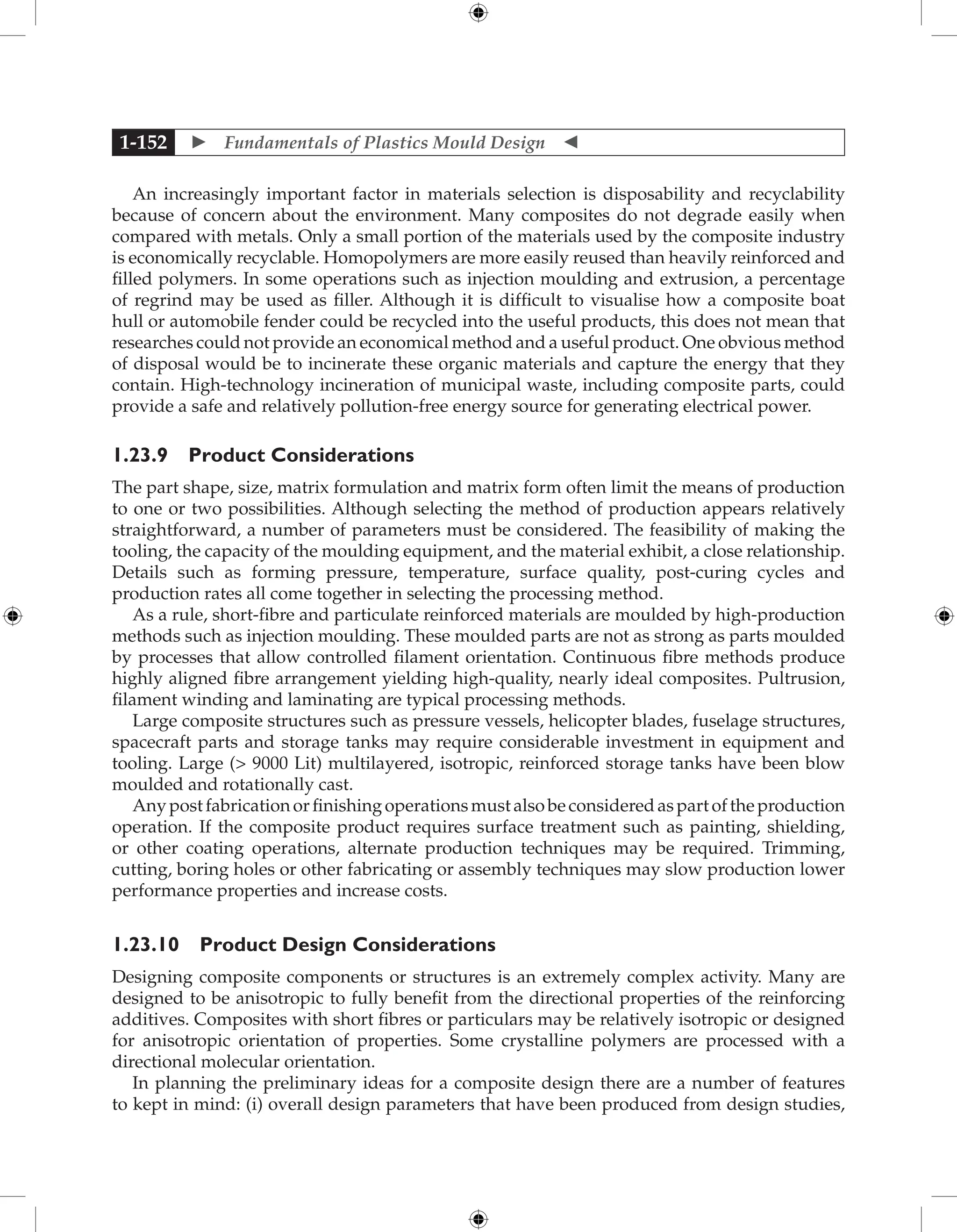

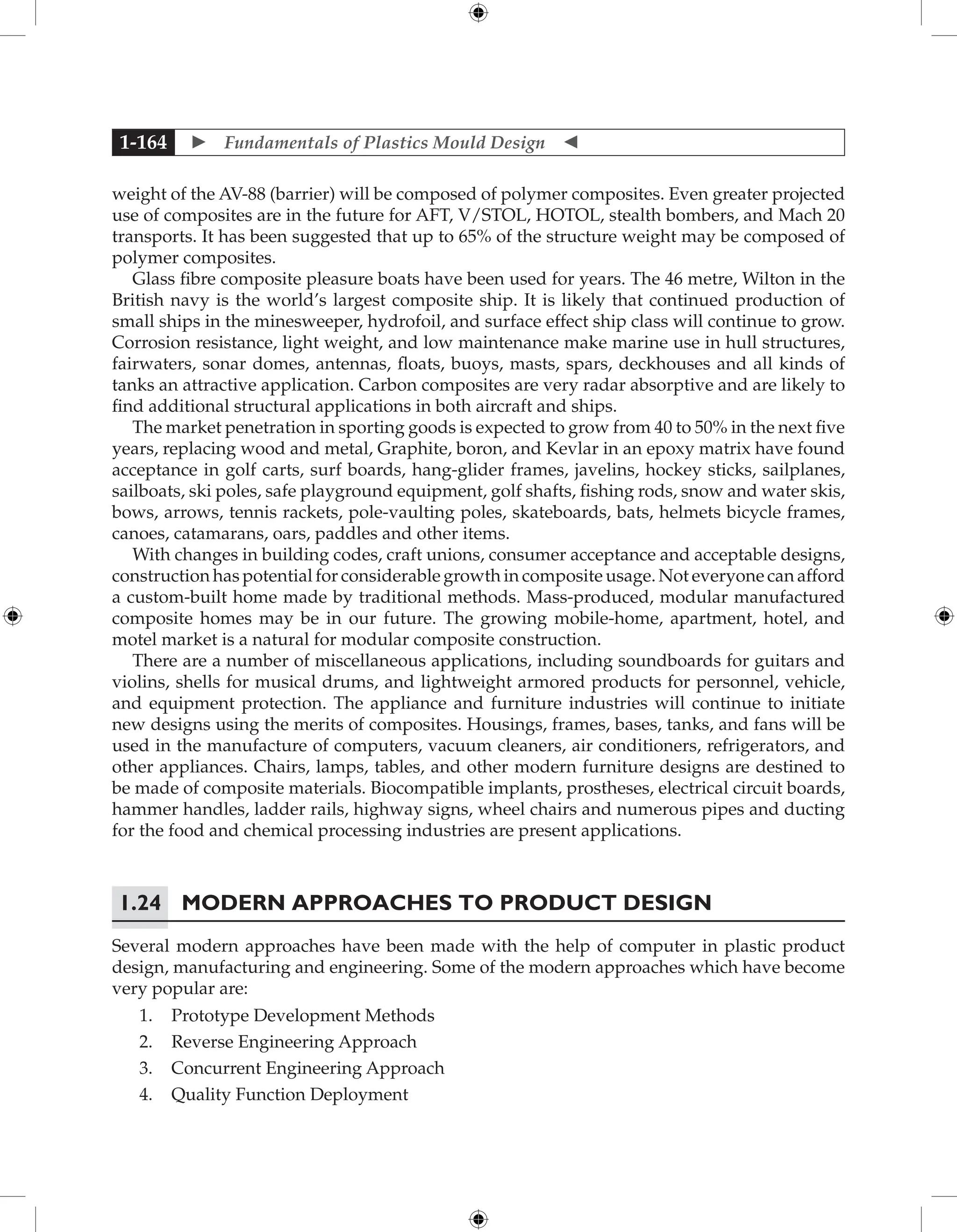

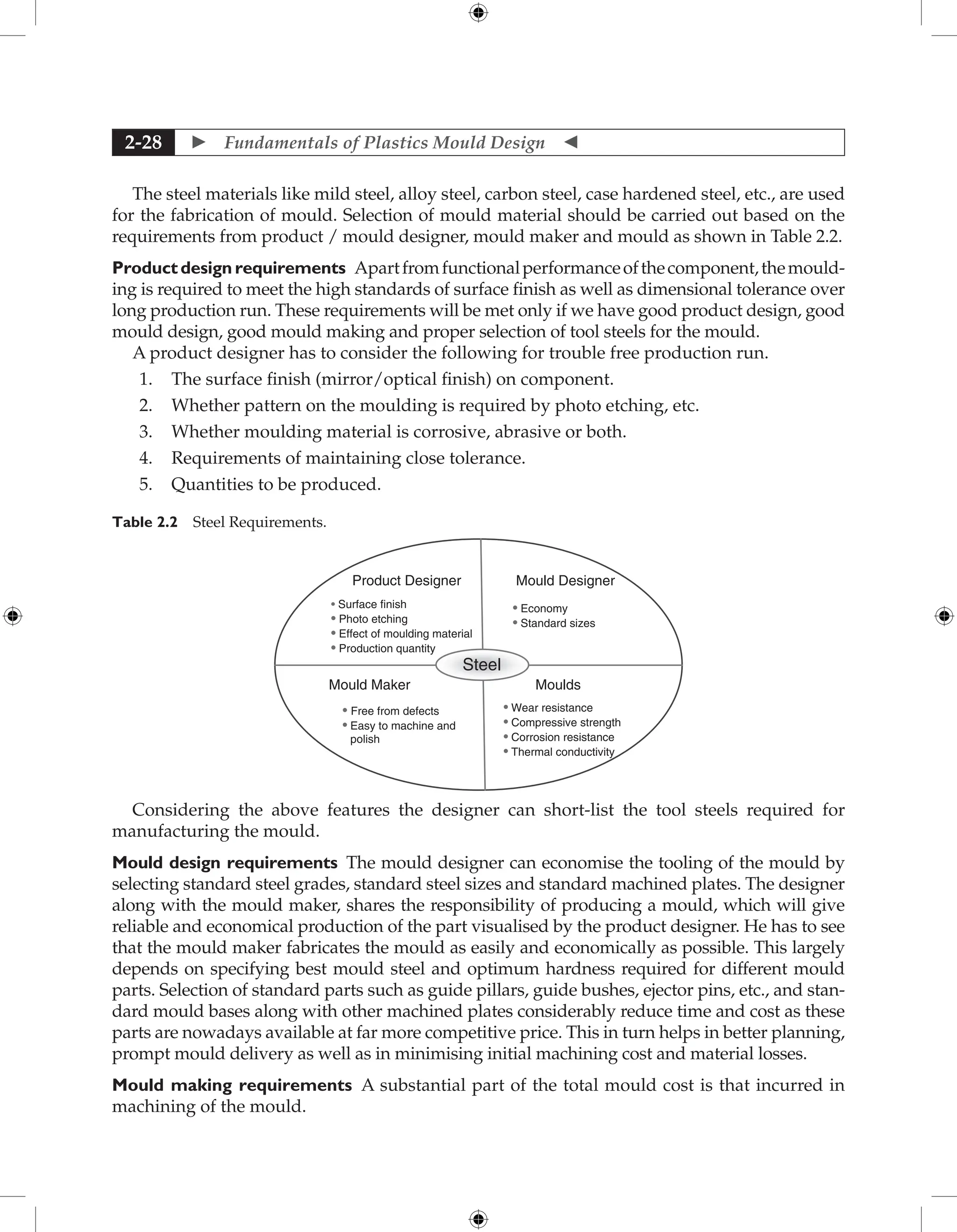

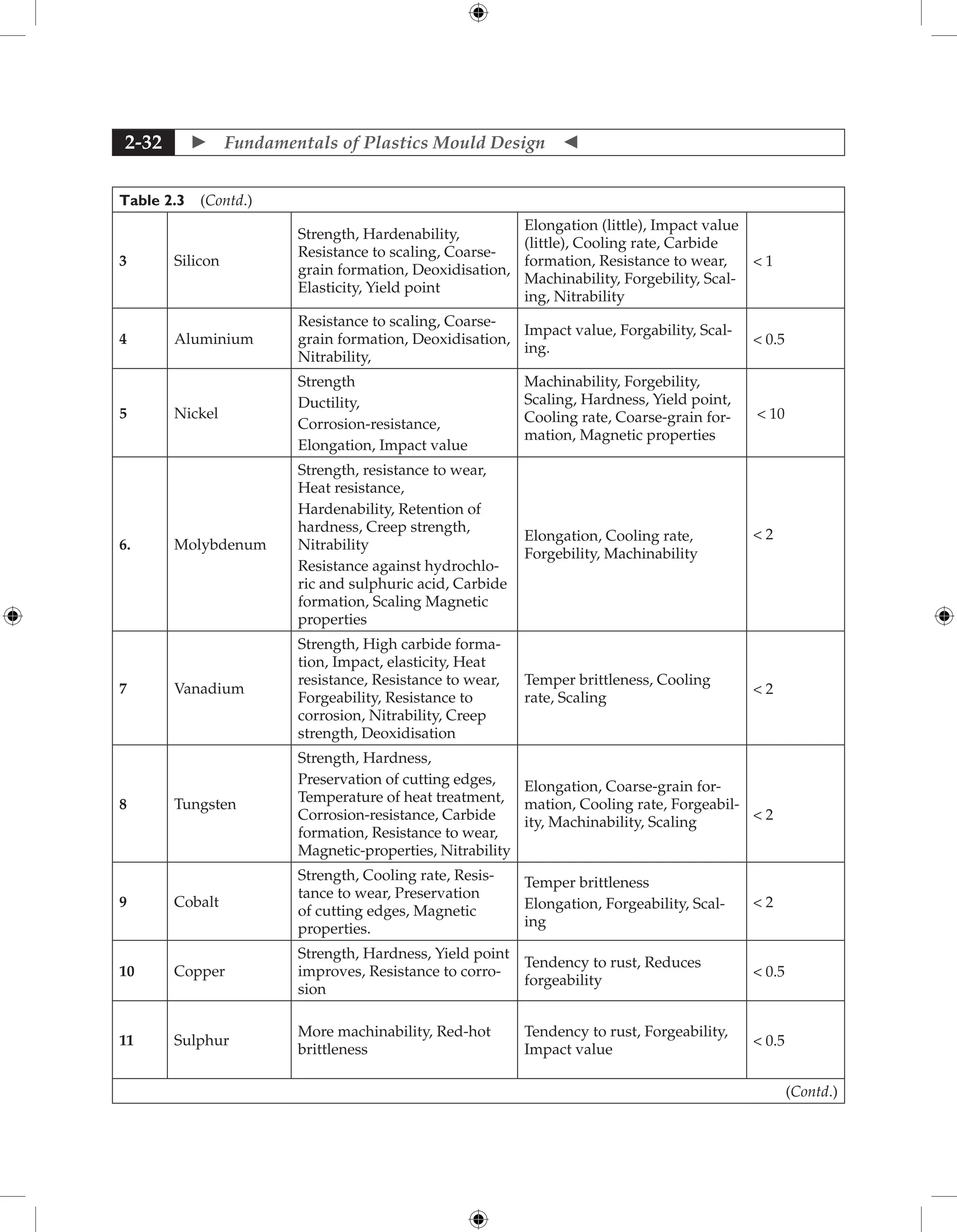

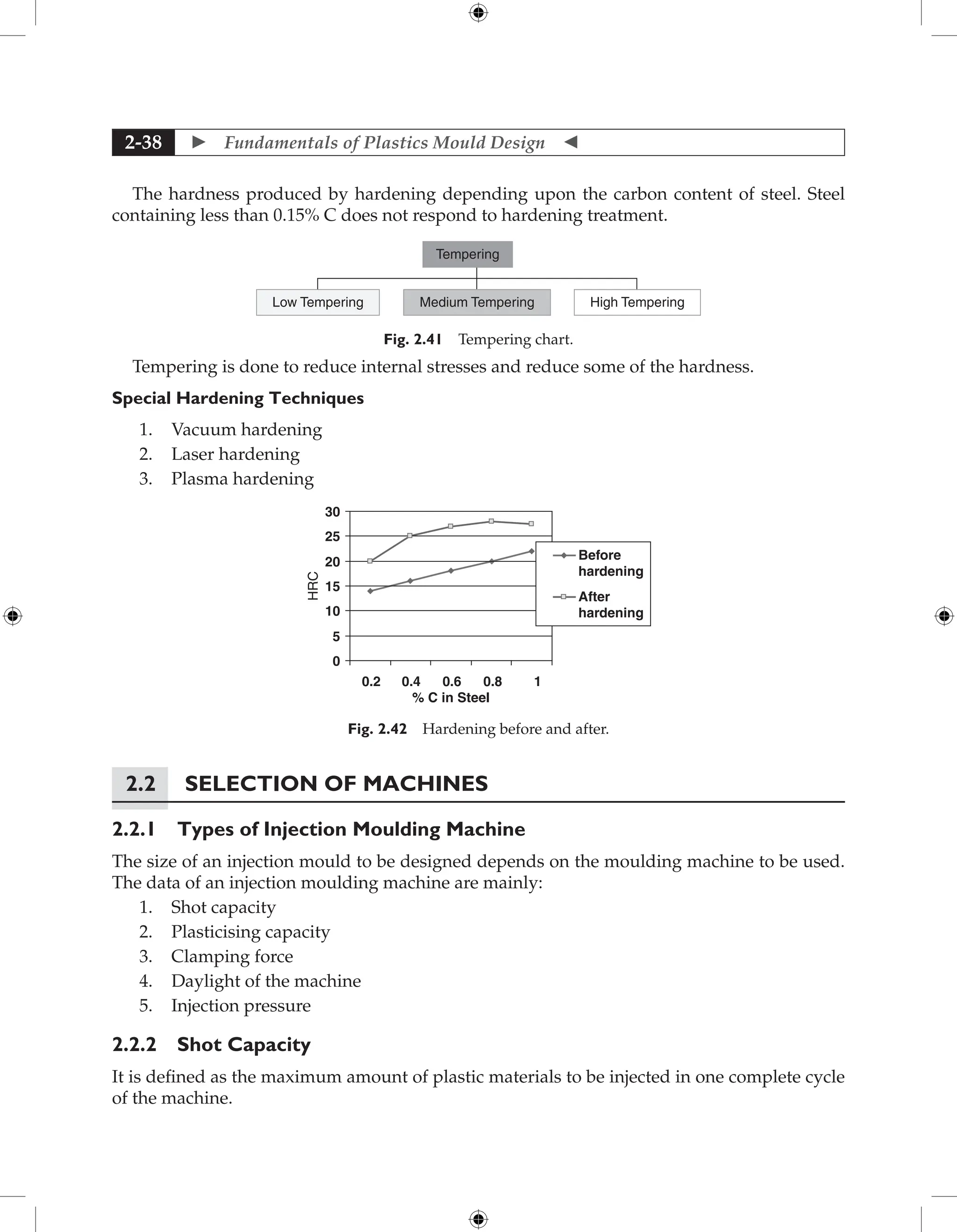

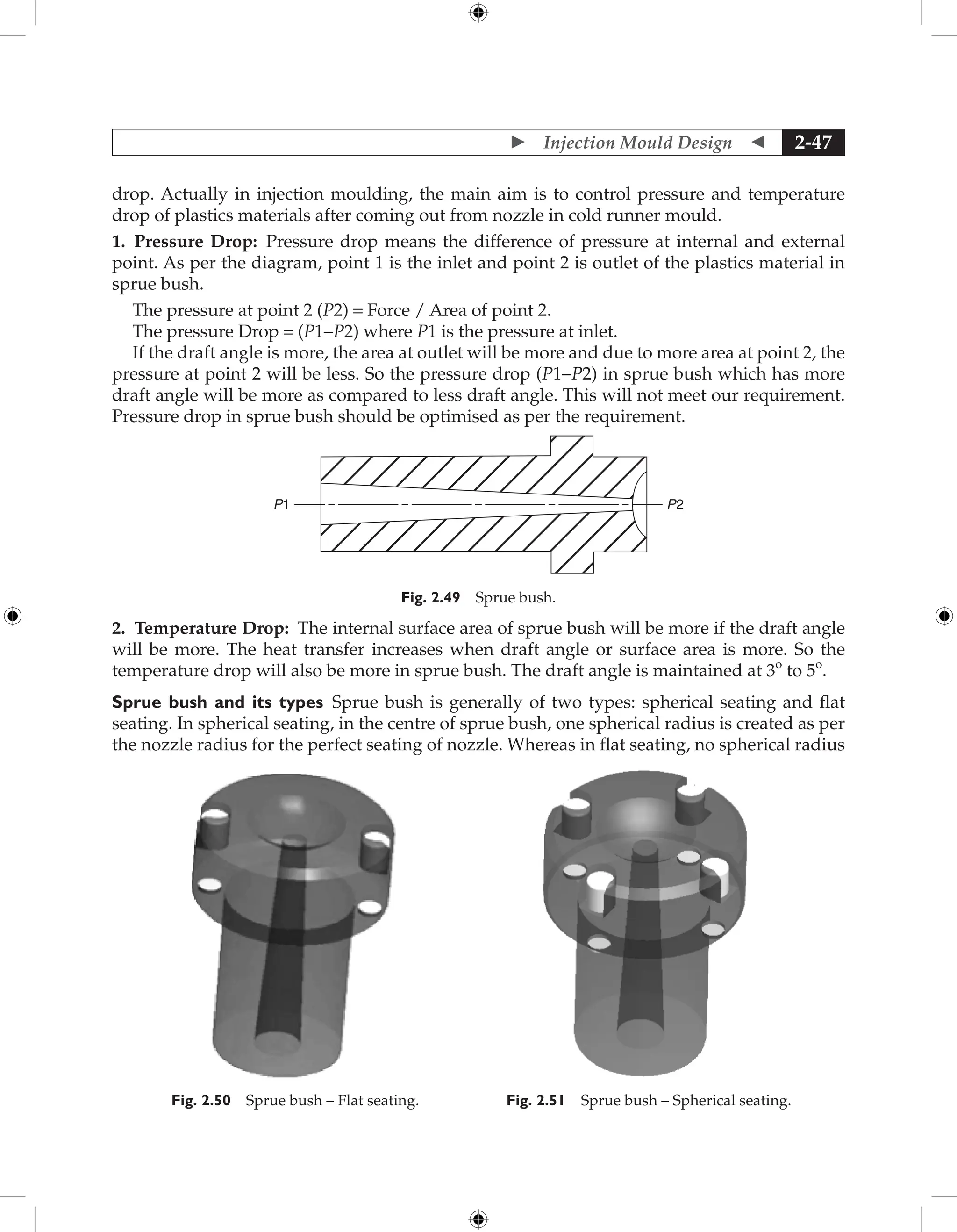

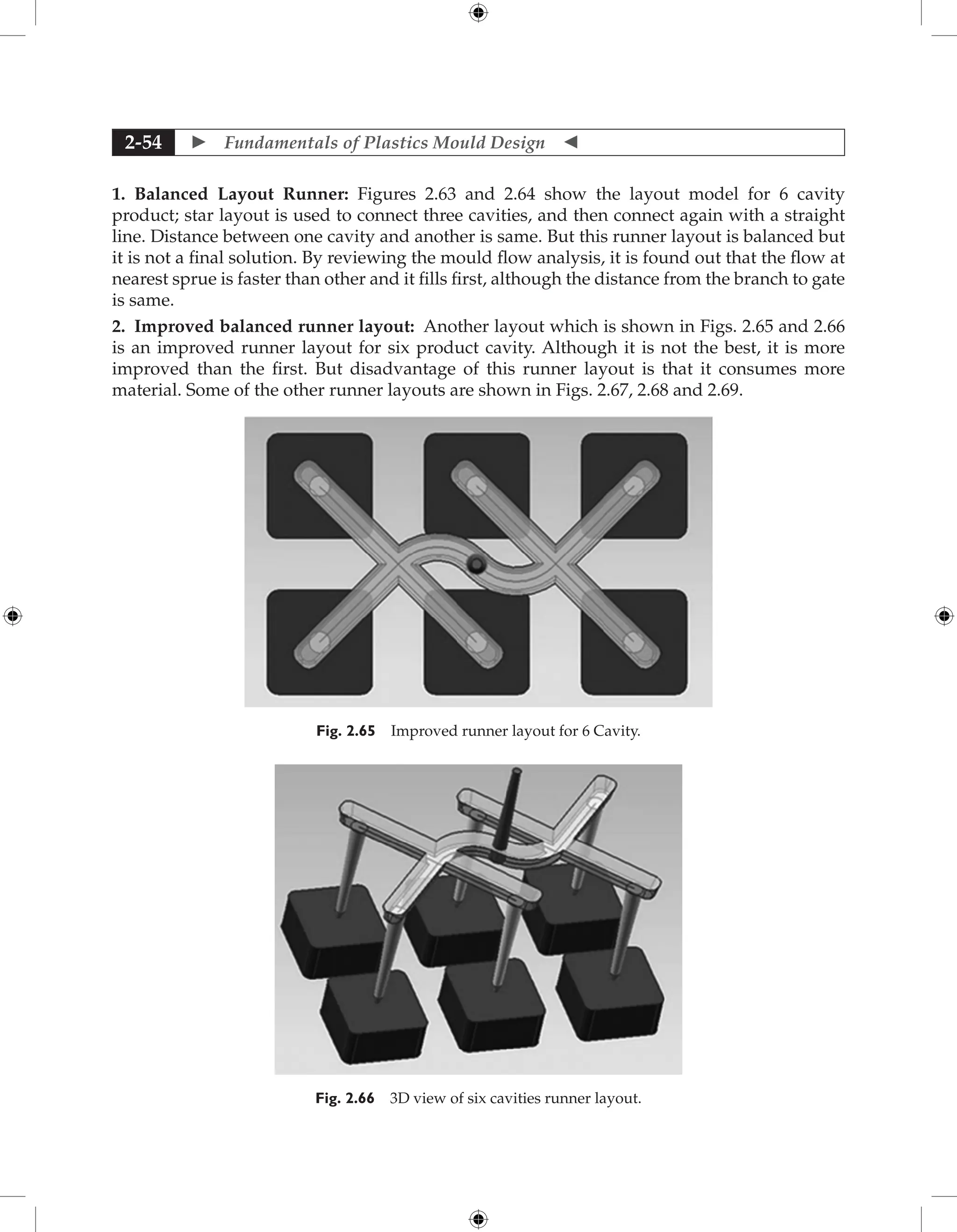

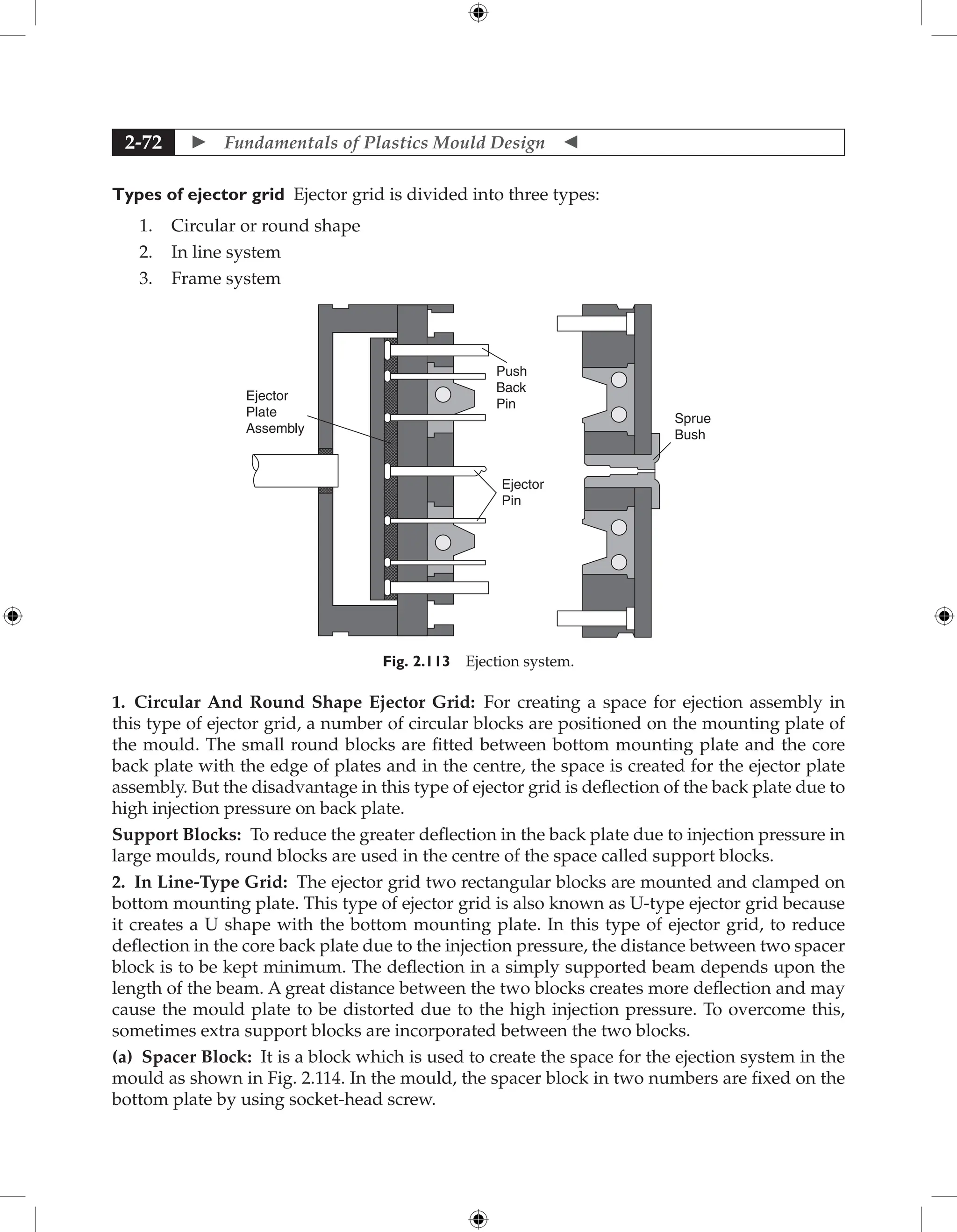

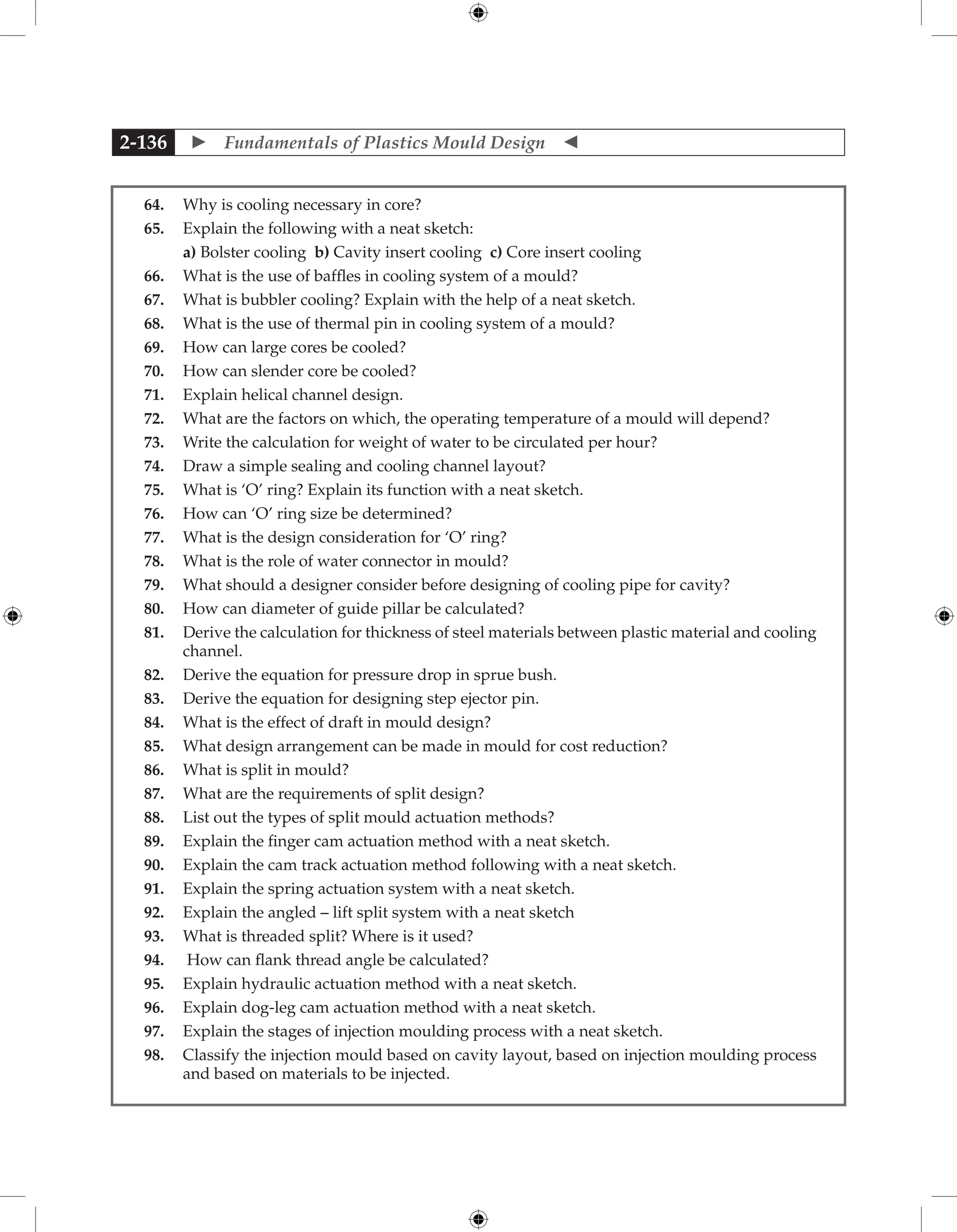

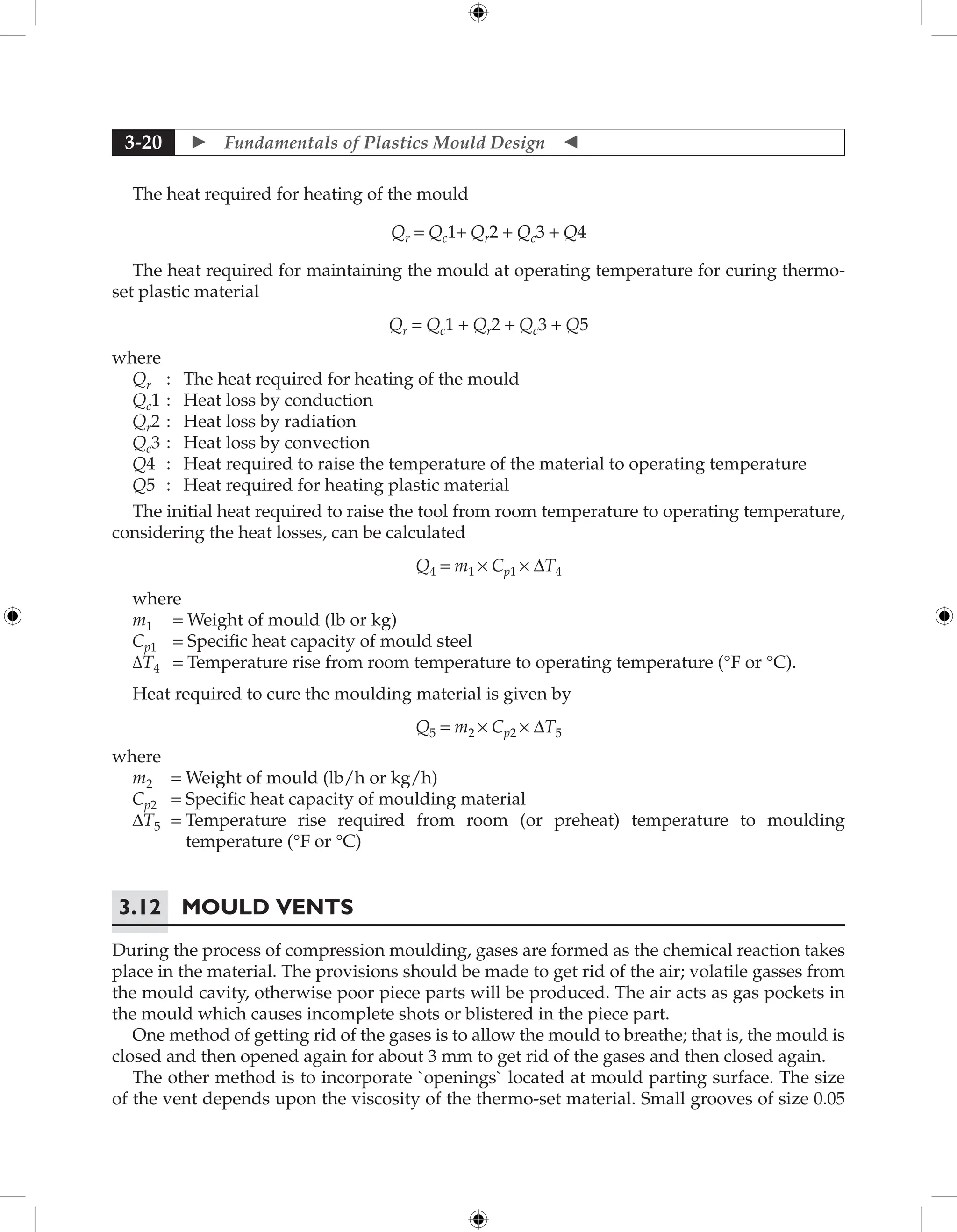

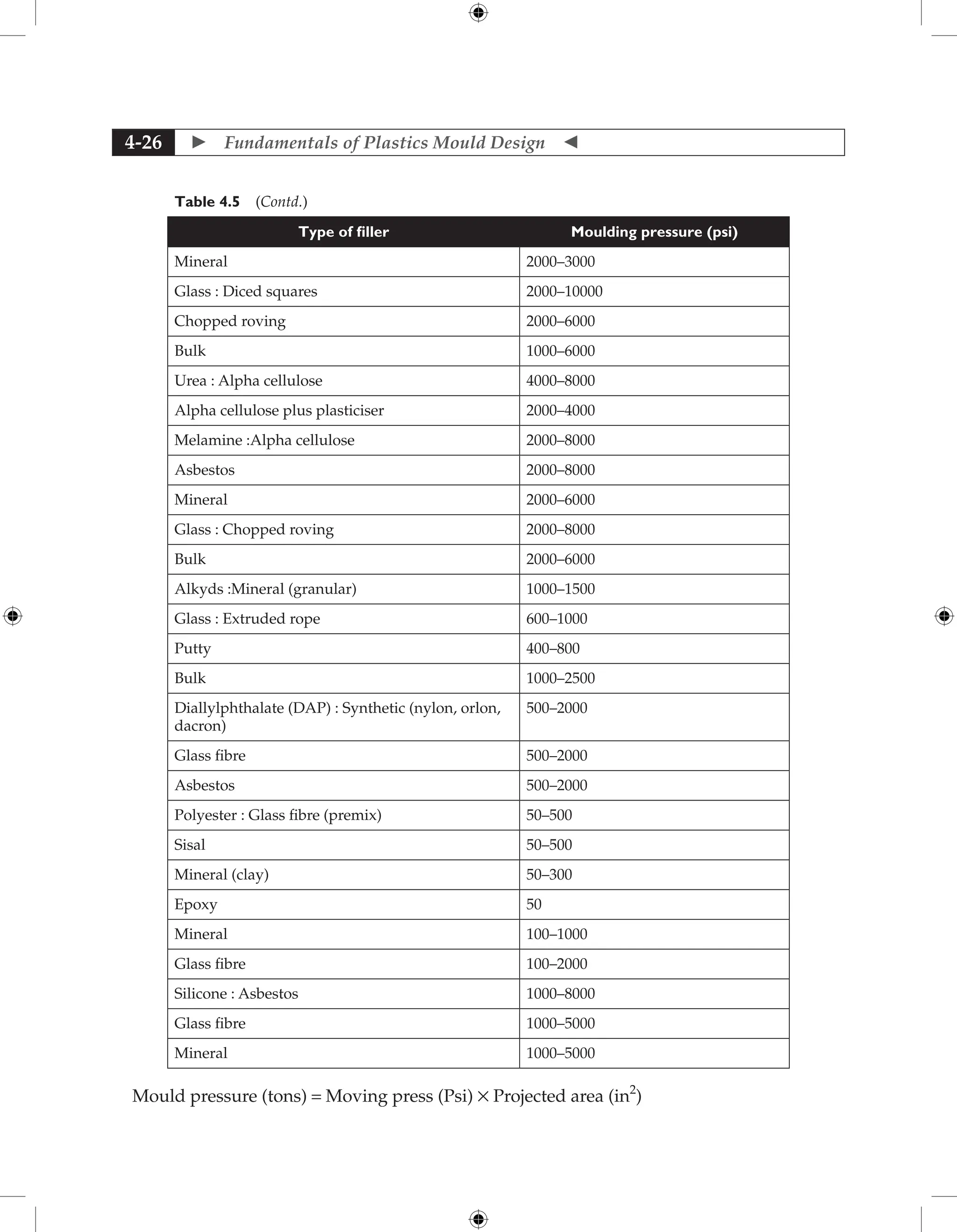

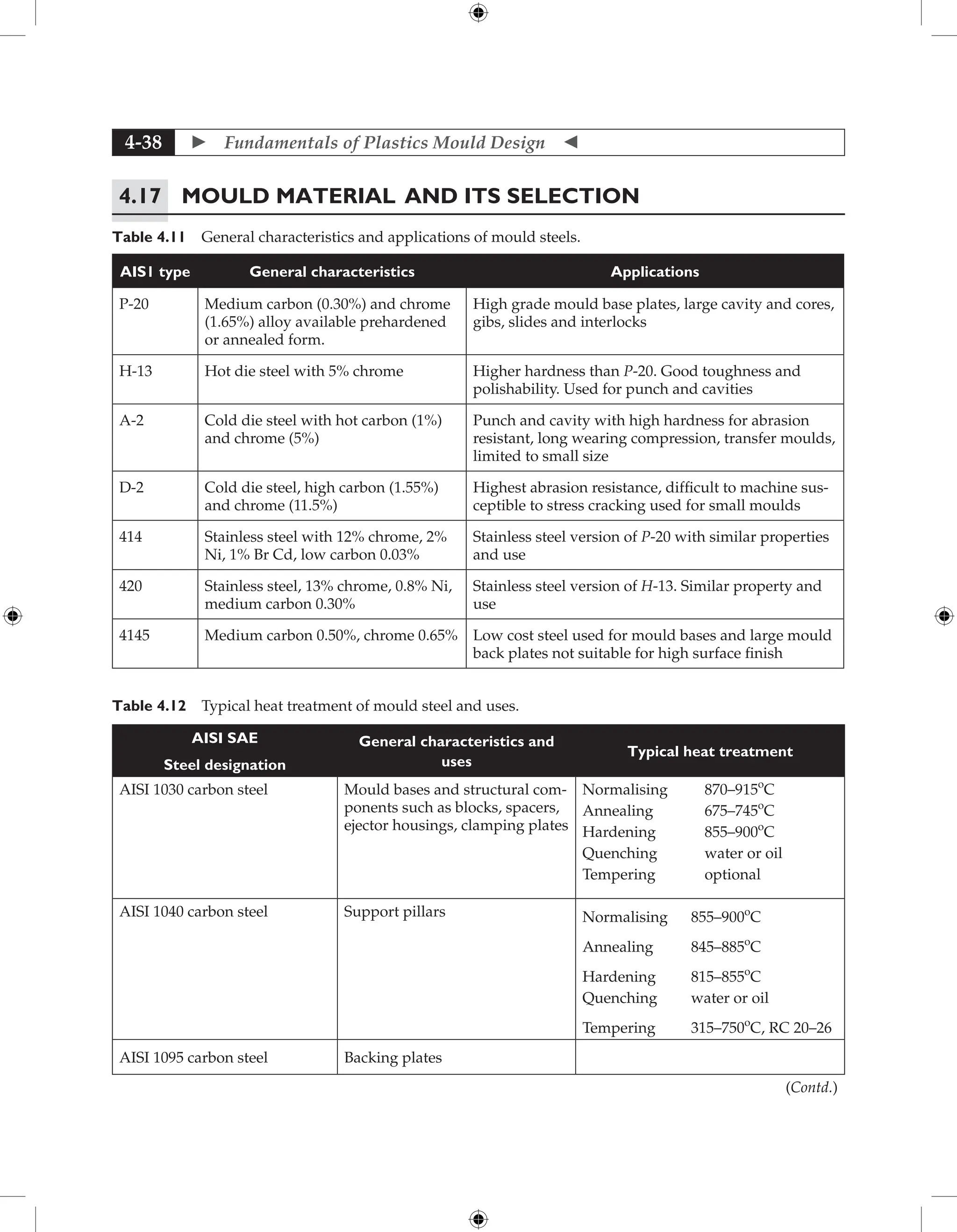

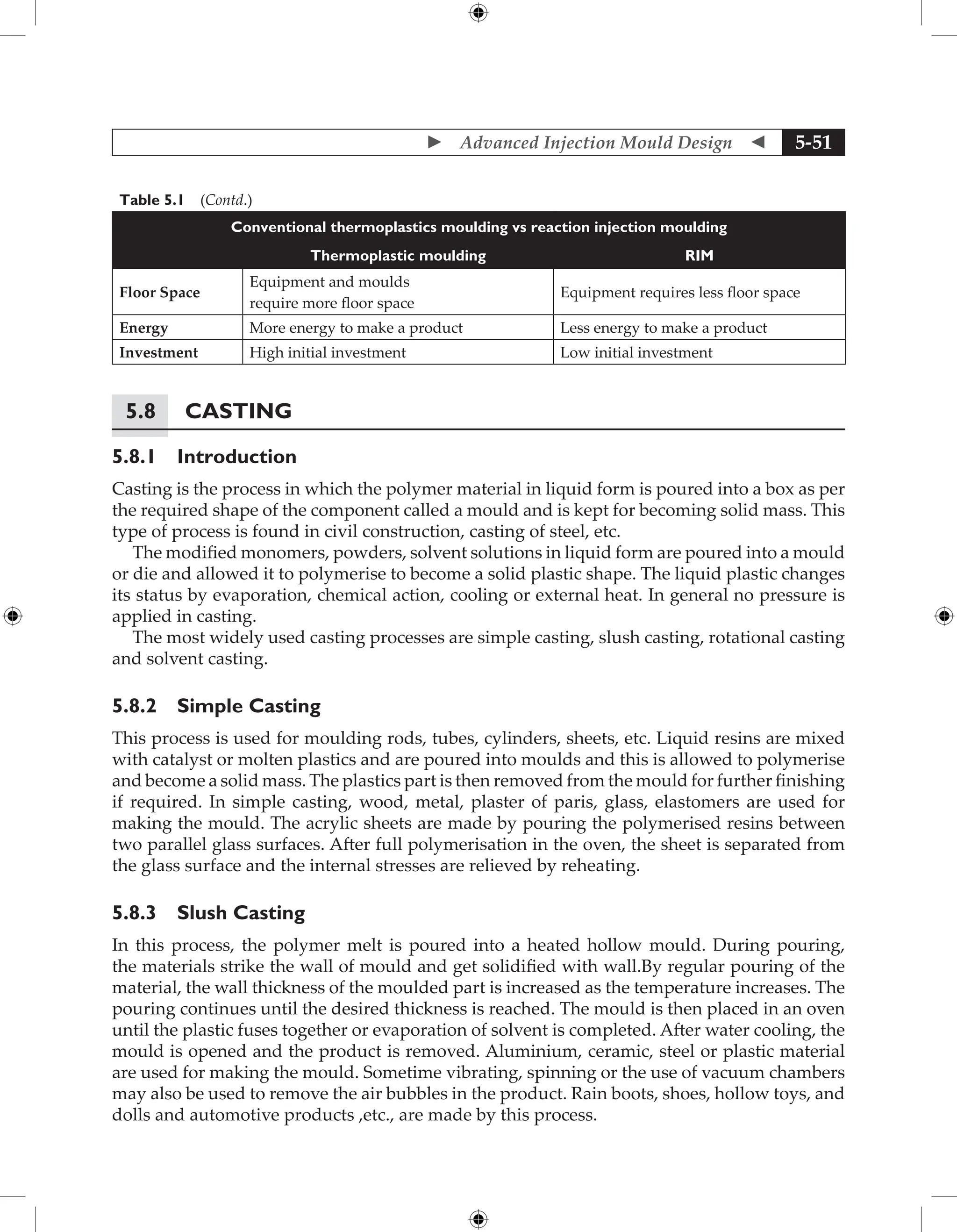

![ Fundamentals of Plastics Mould Design

2-74

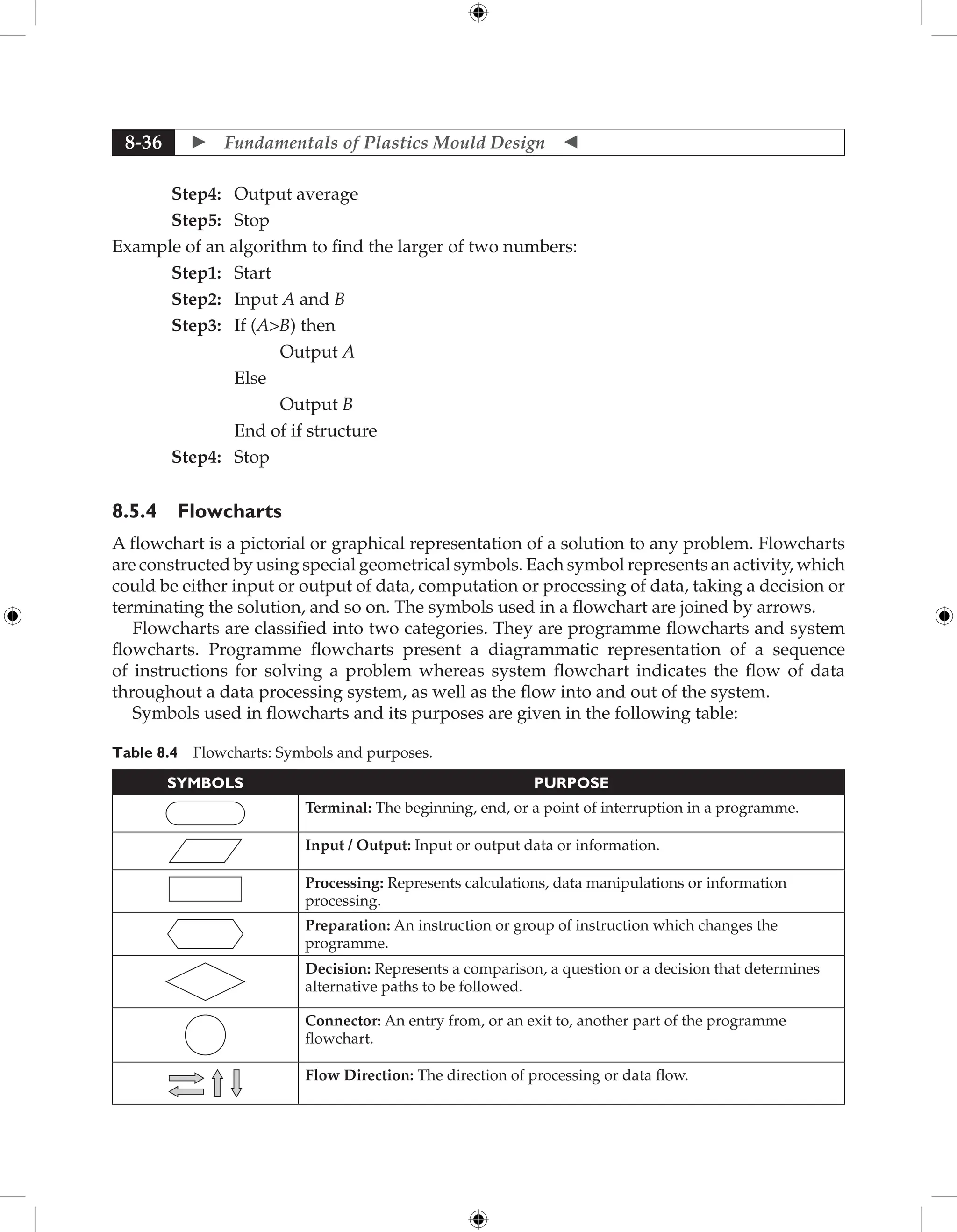

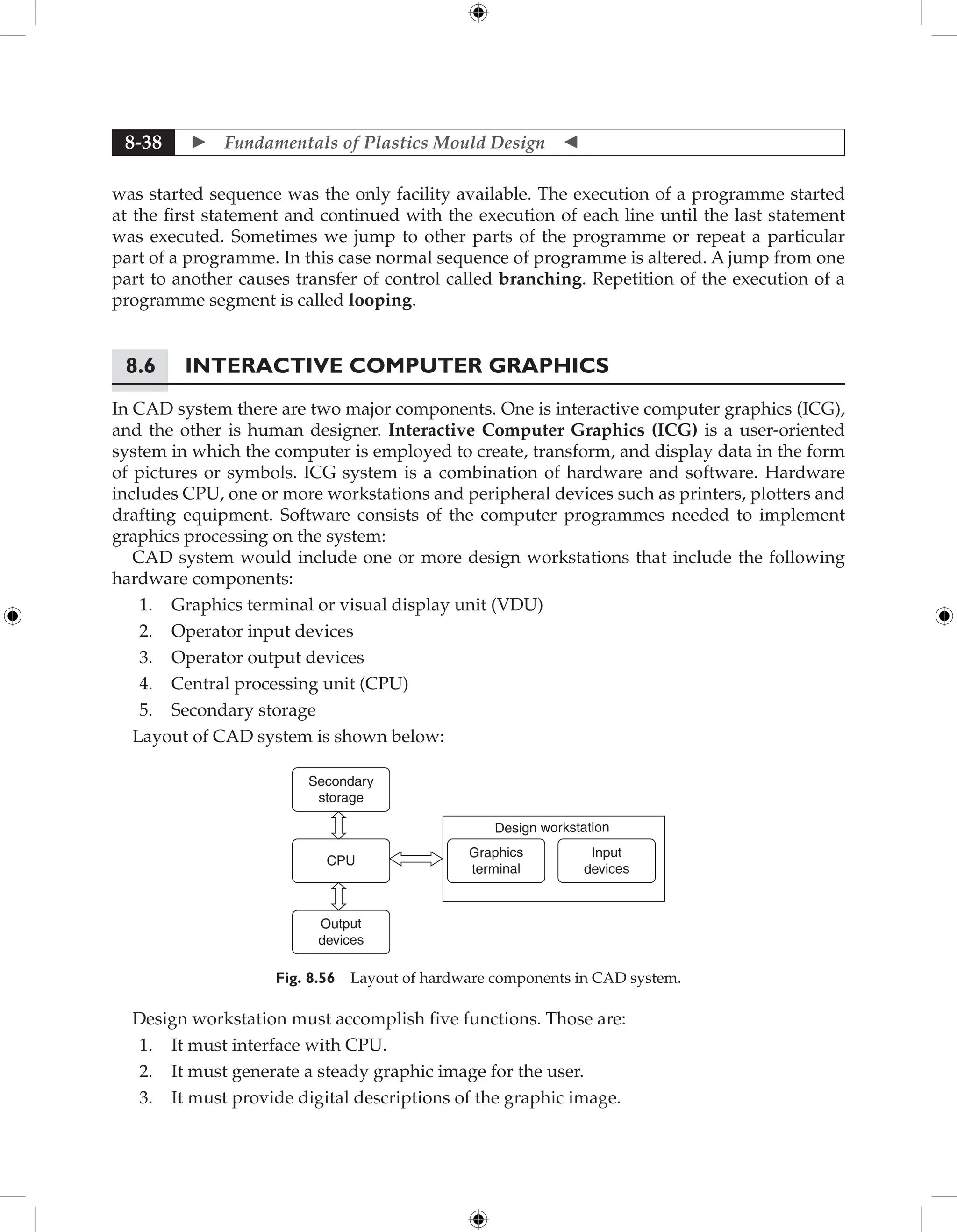

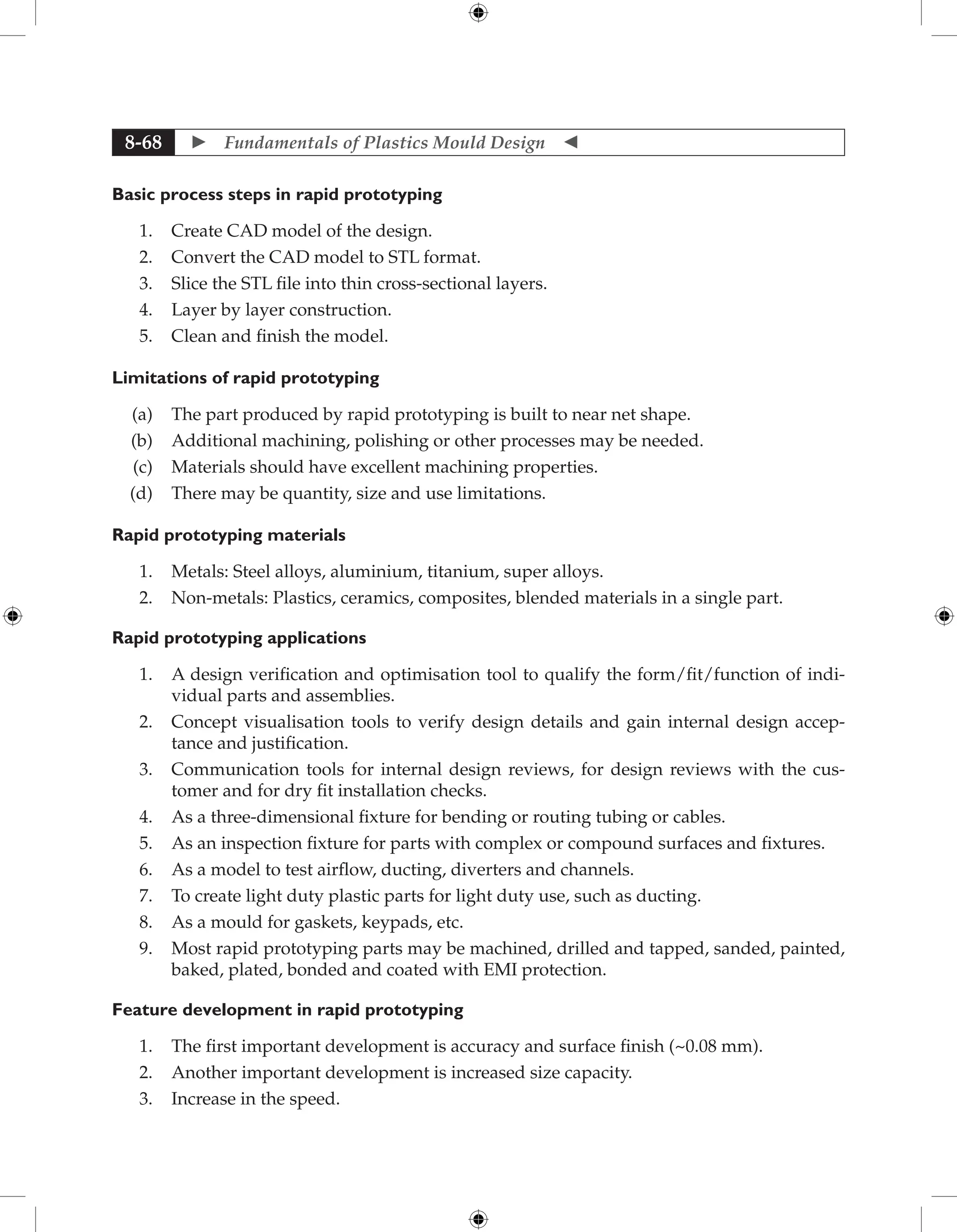

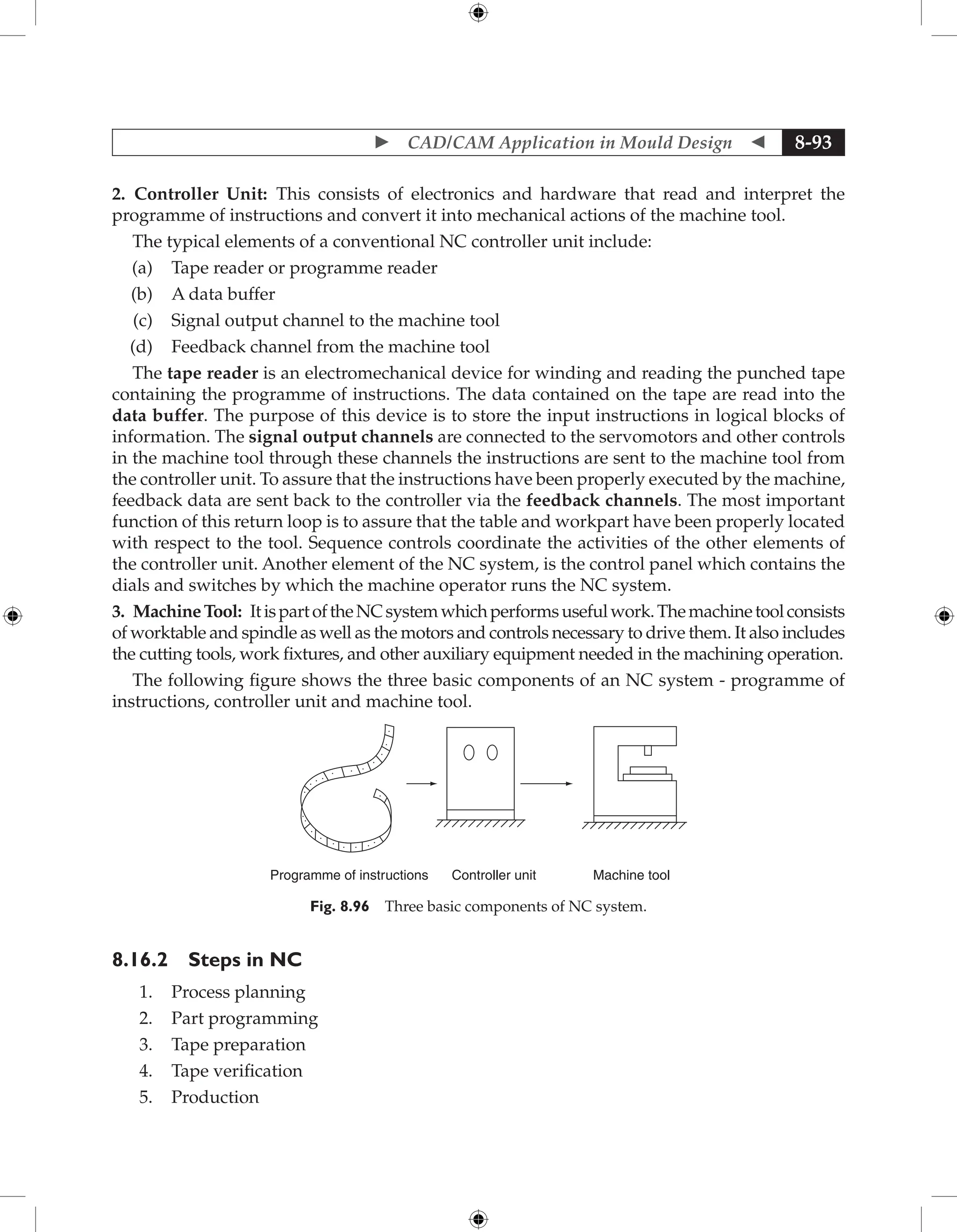

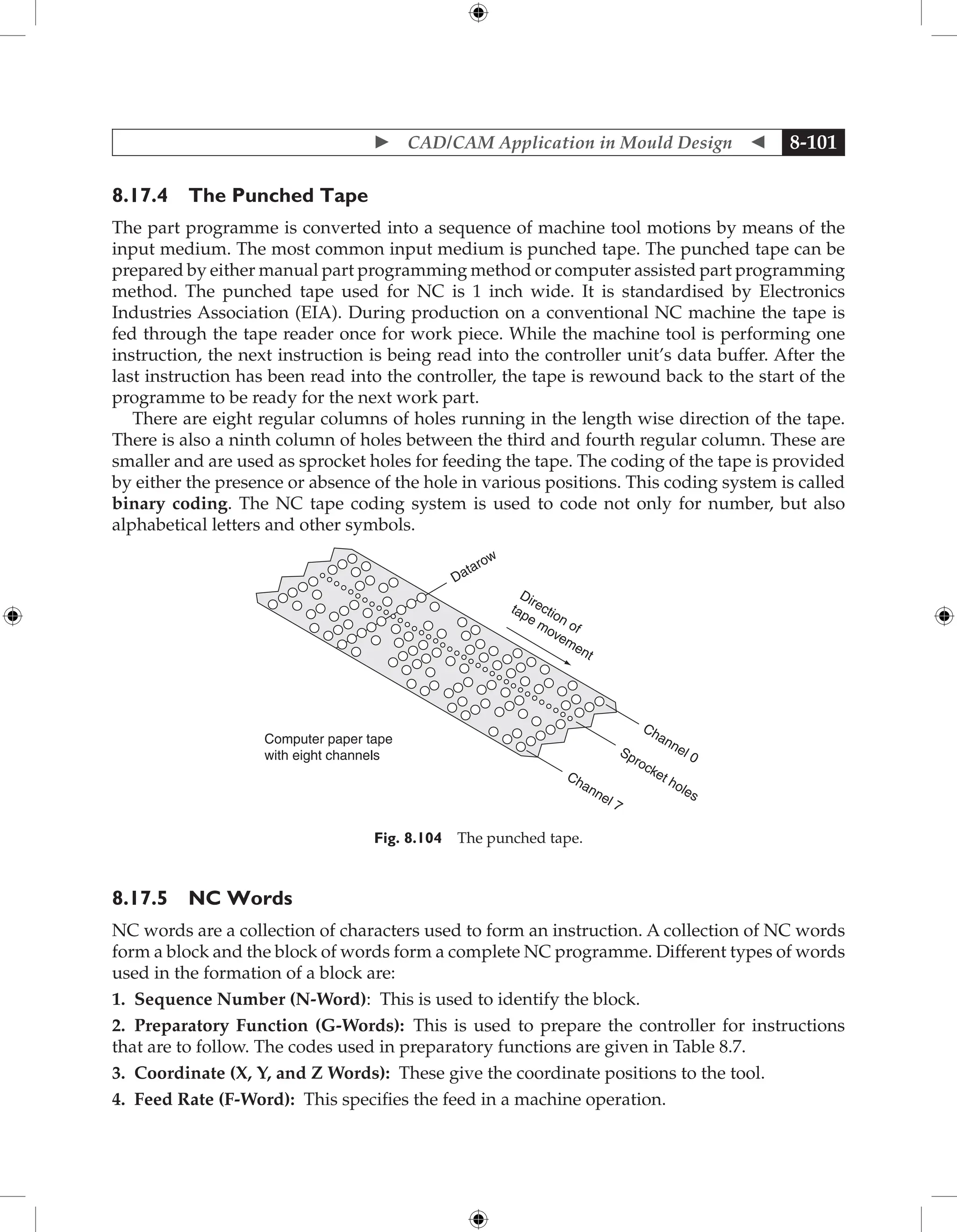

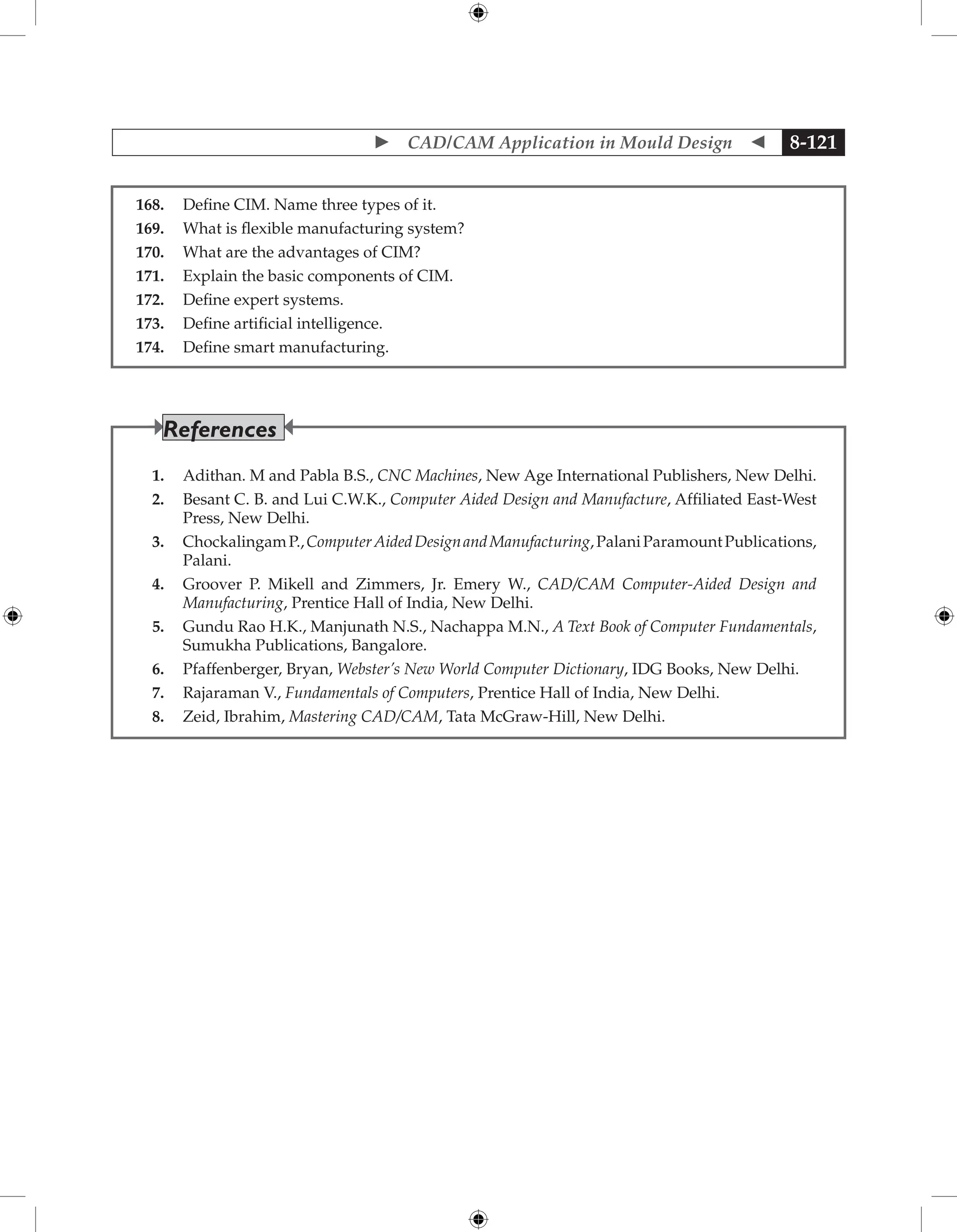

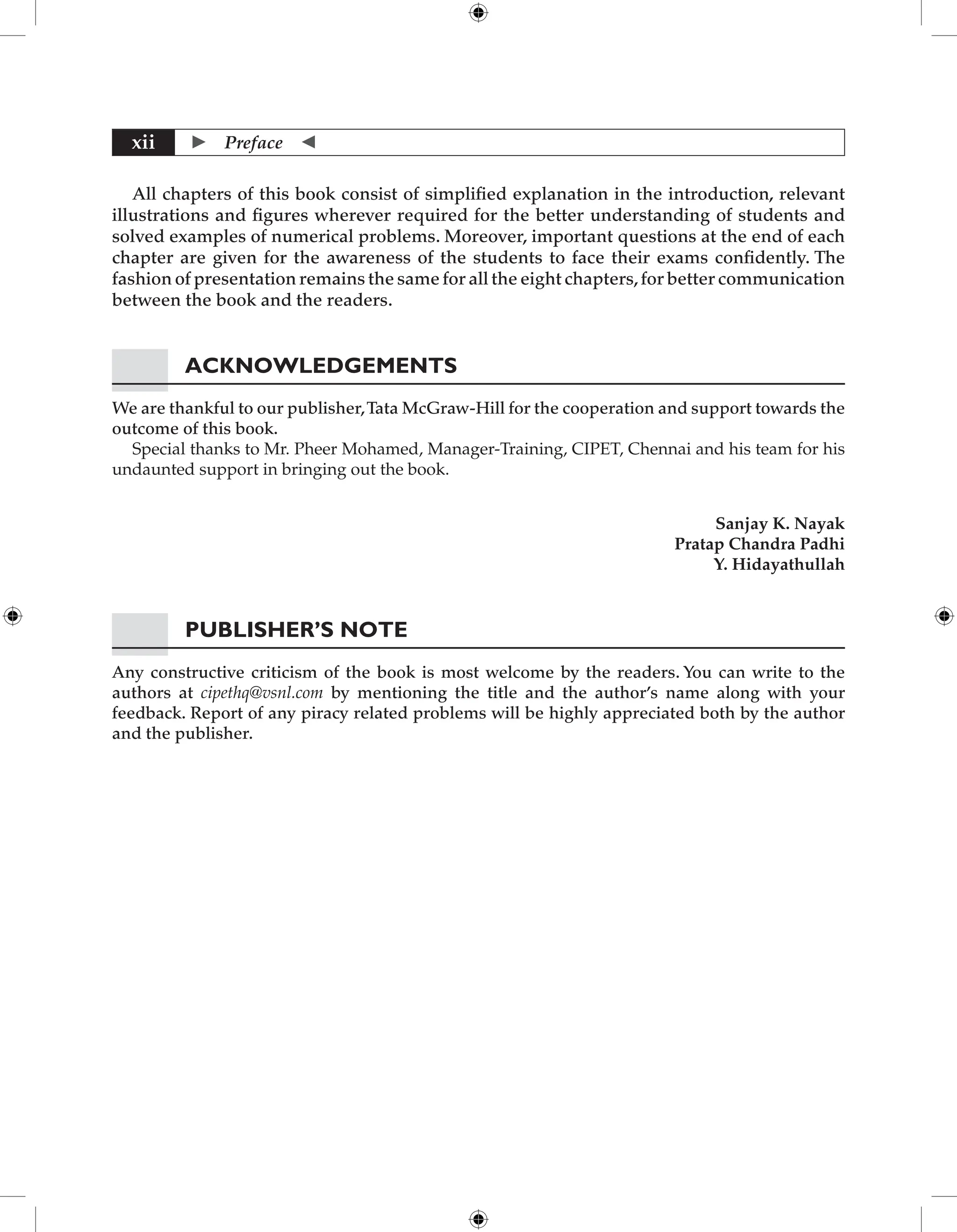

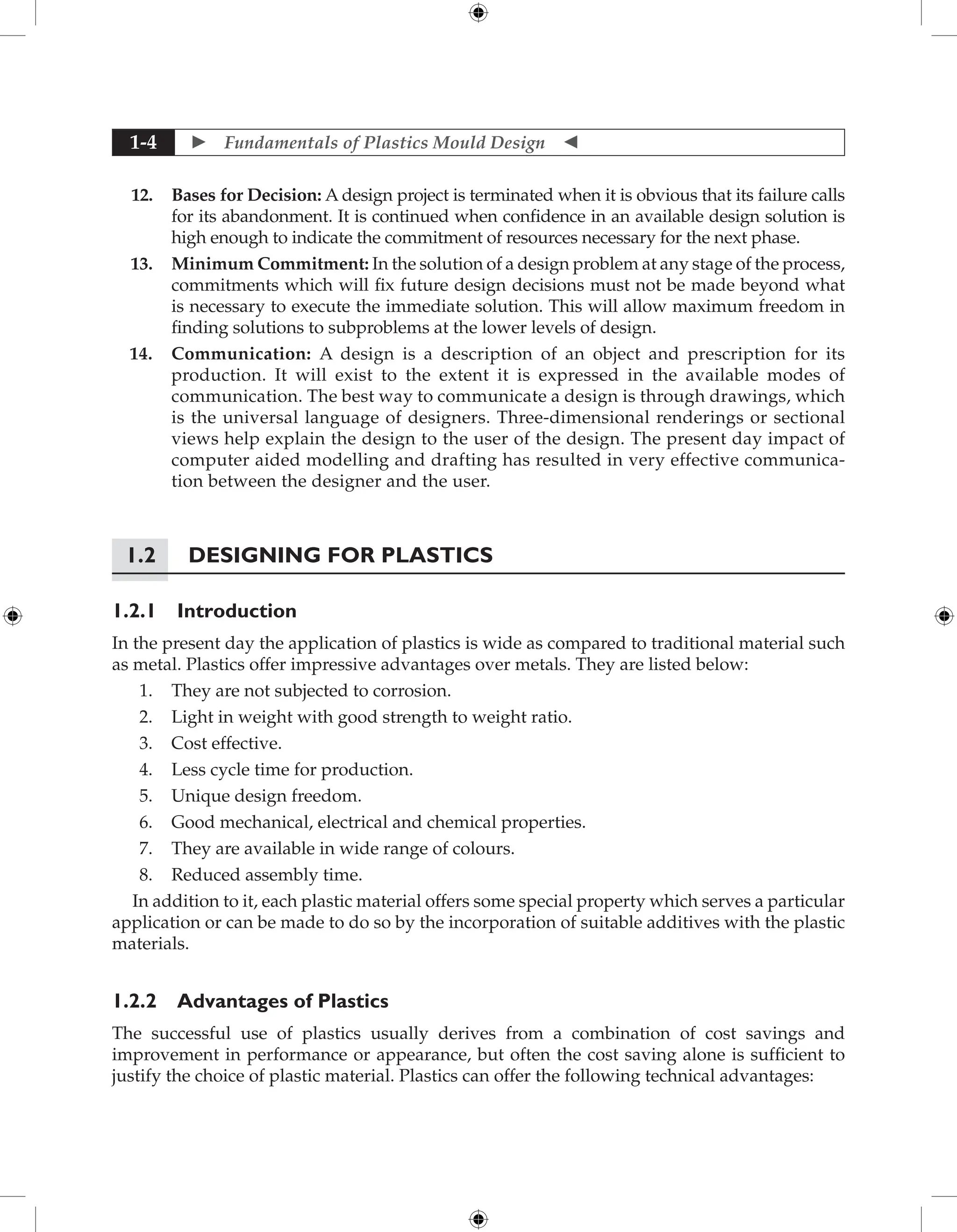

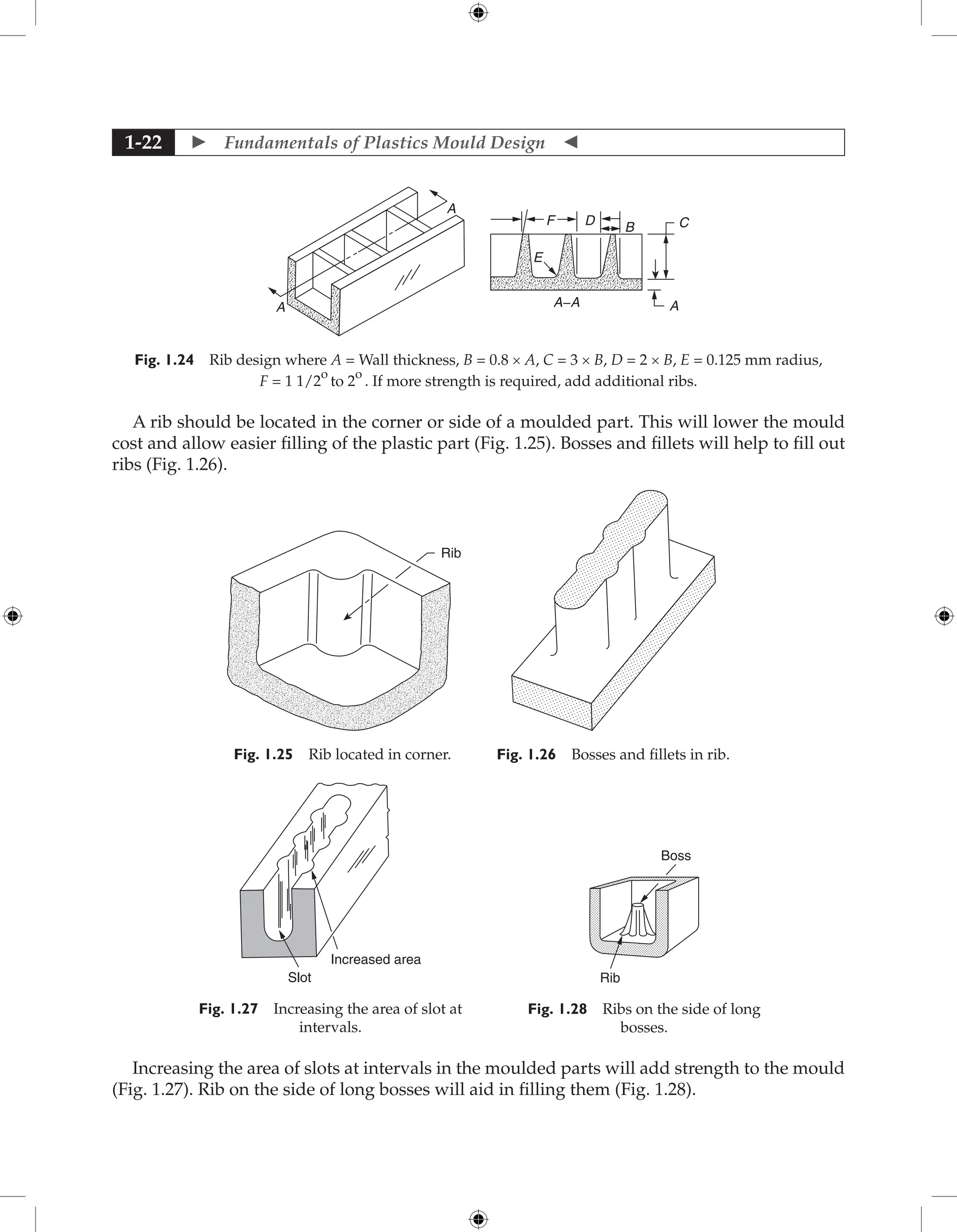

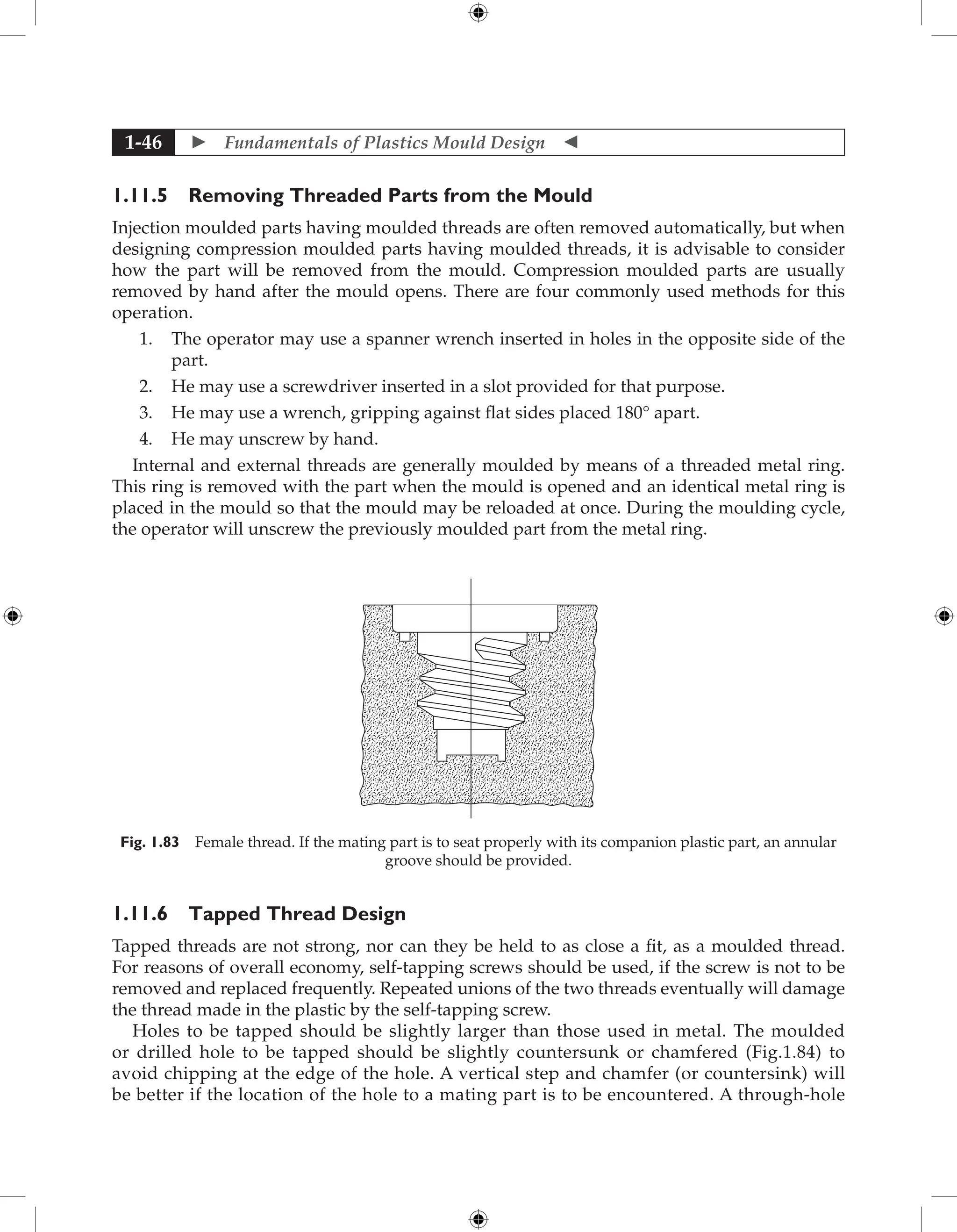

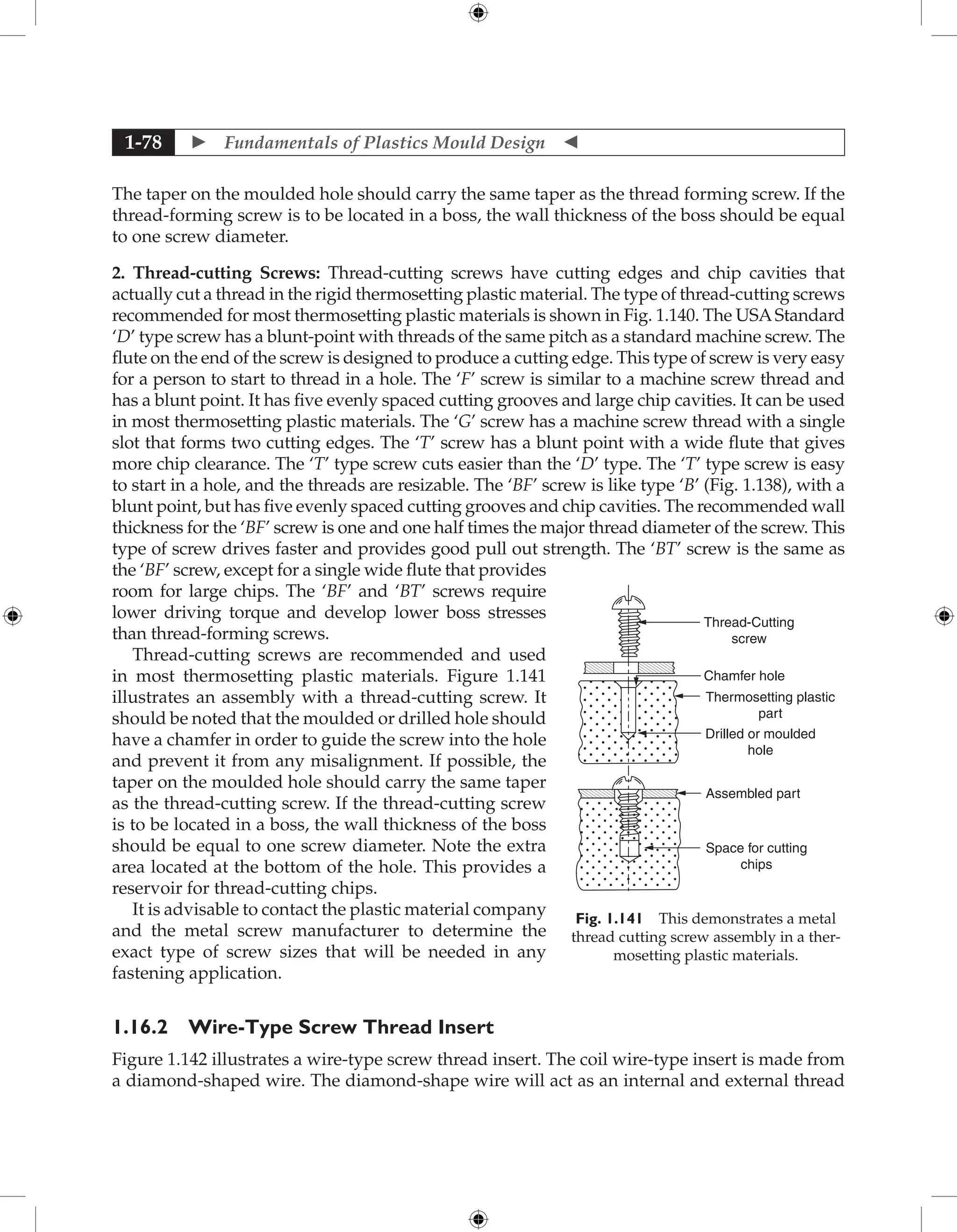

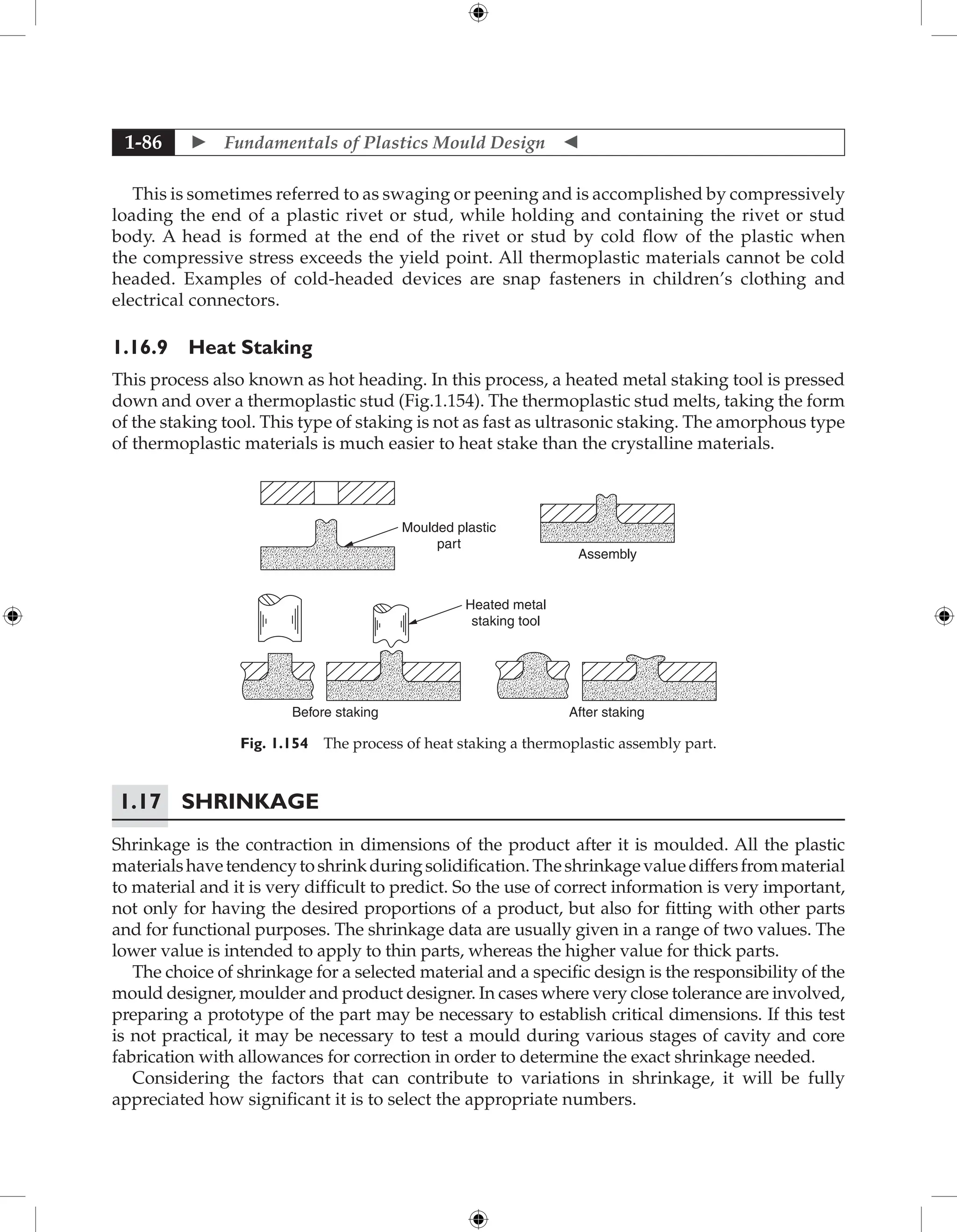

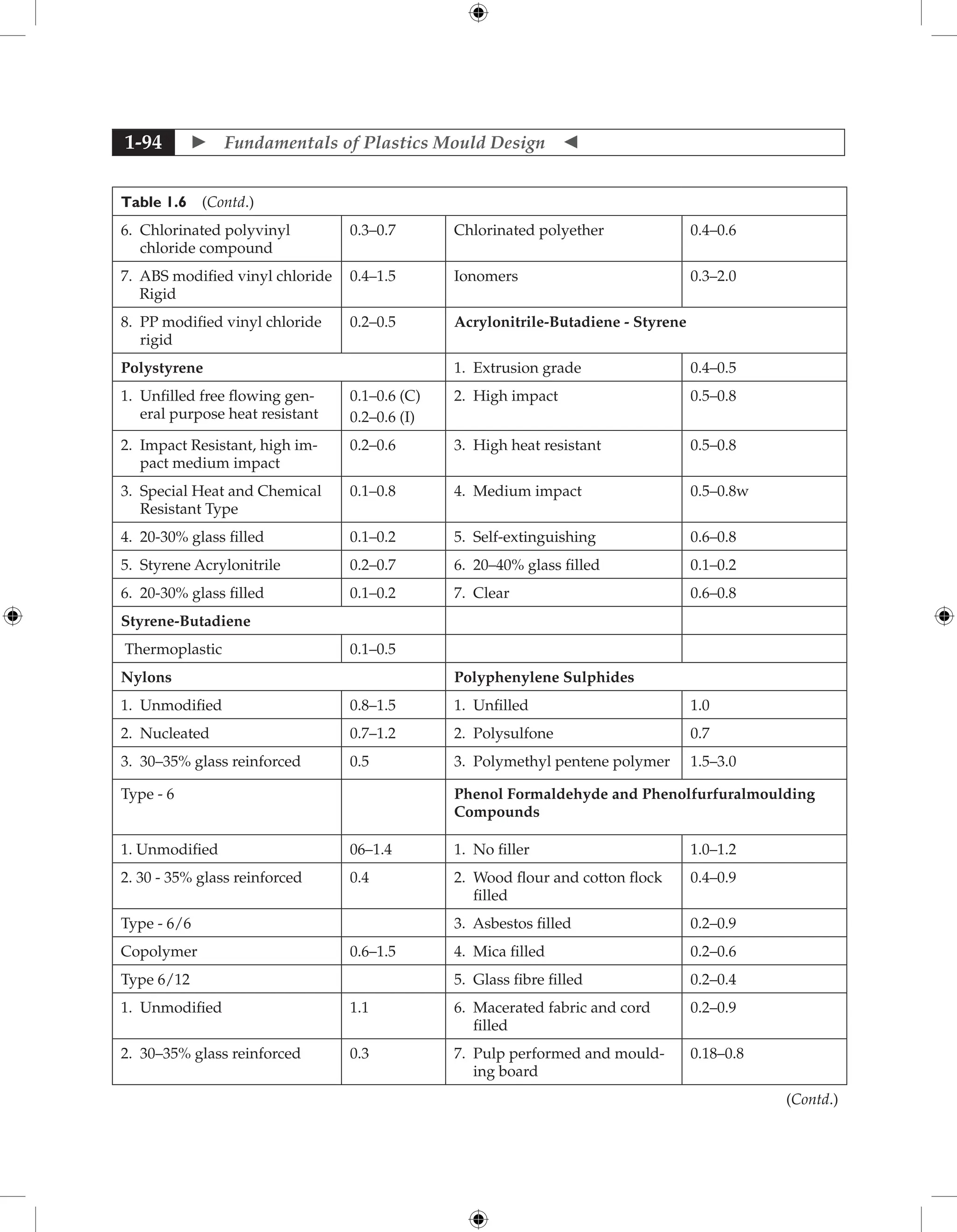

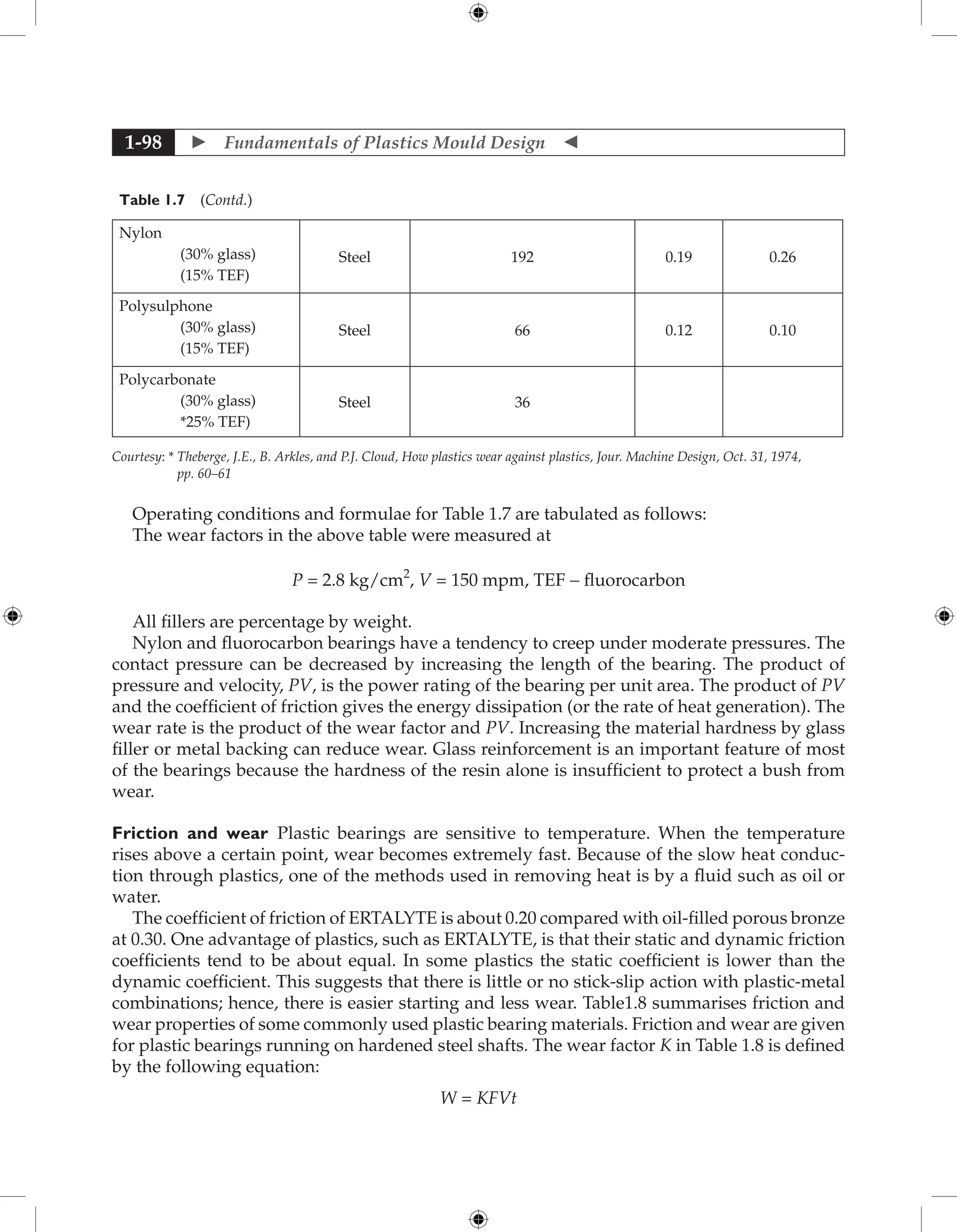

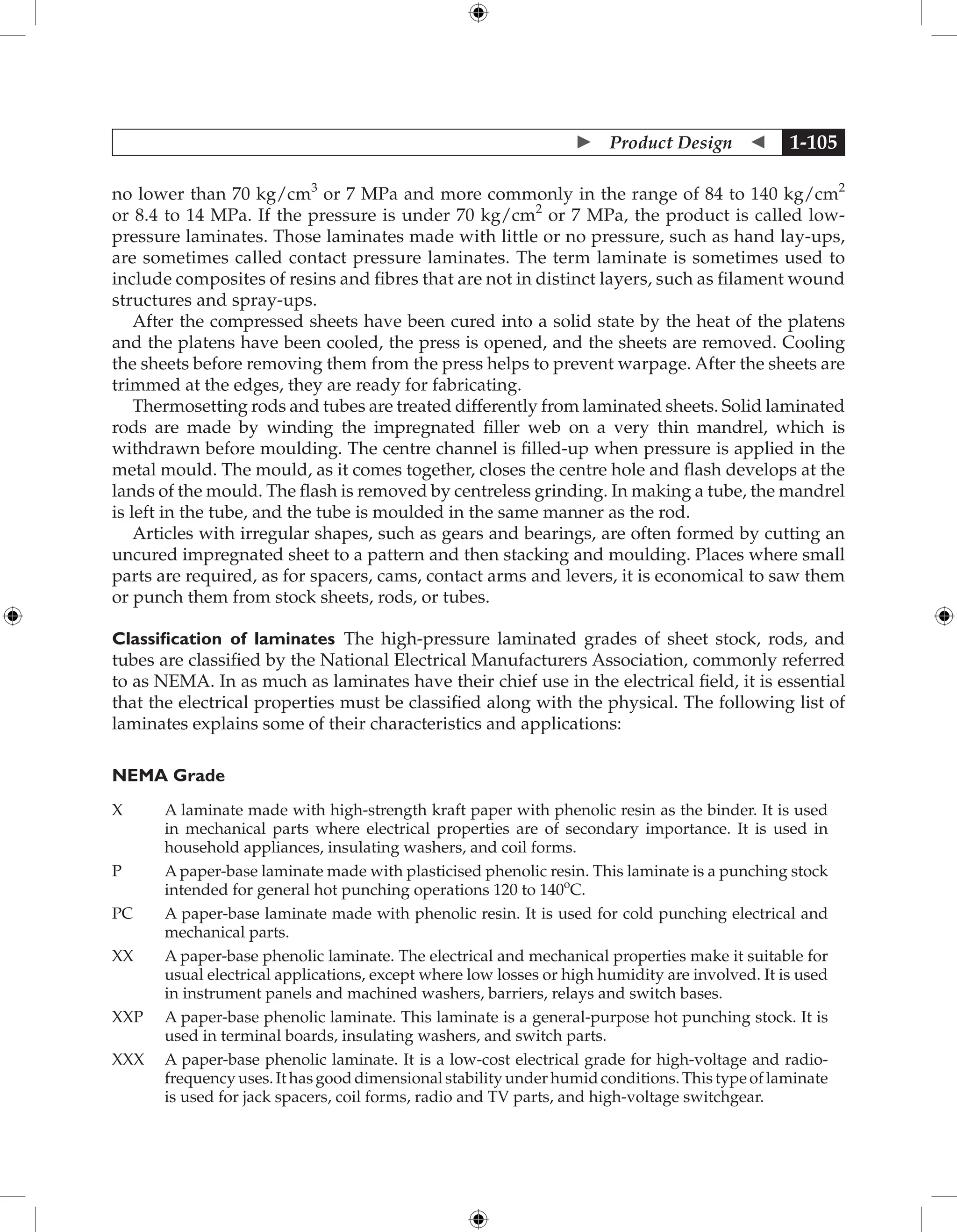

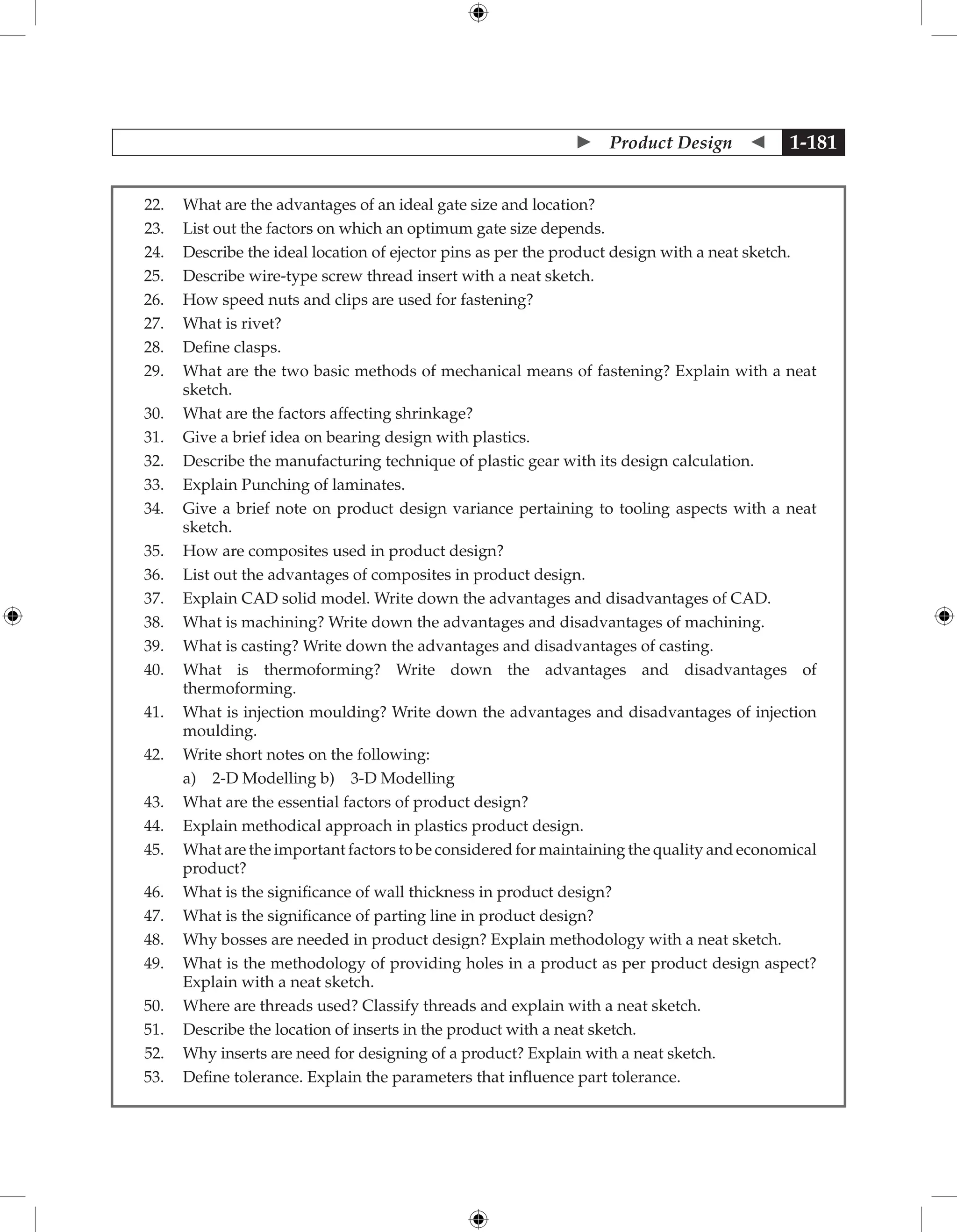

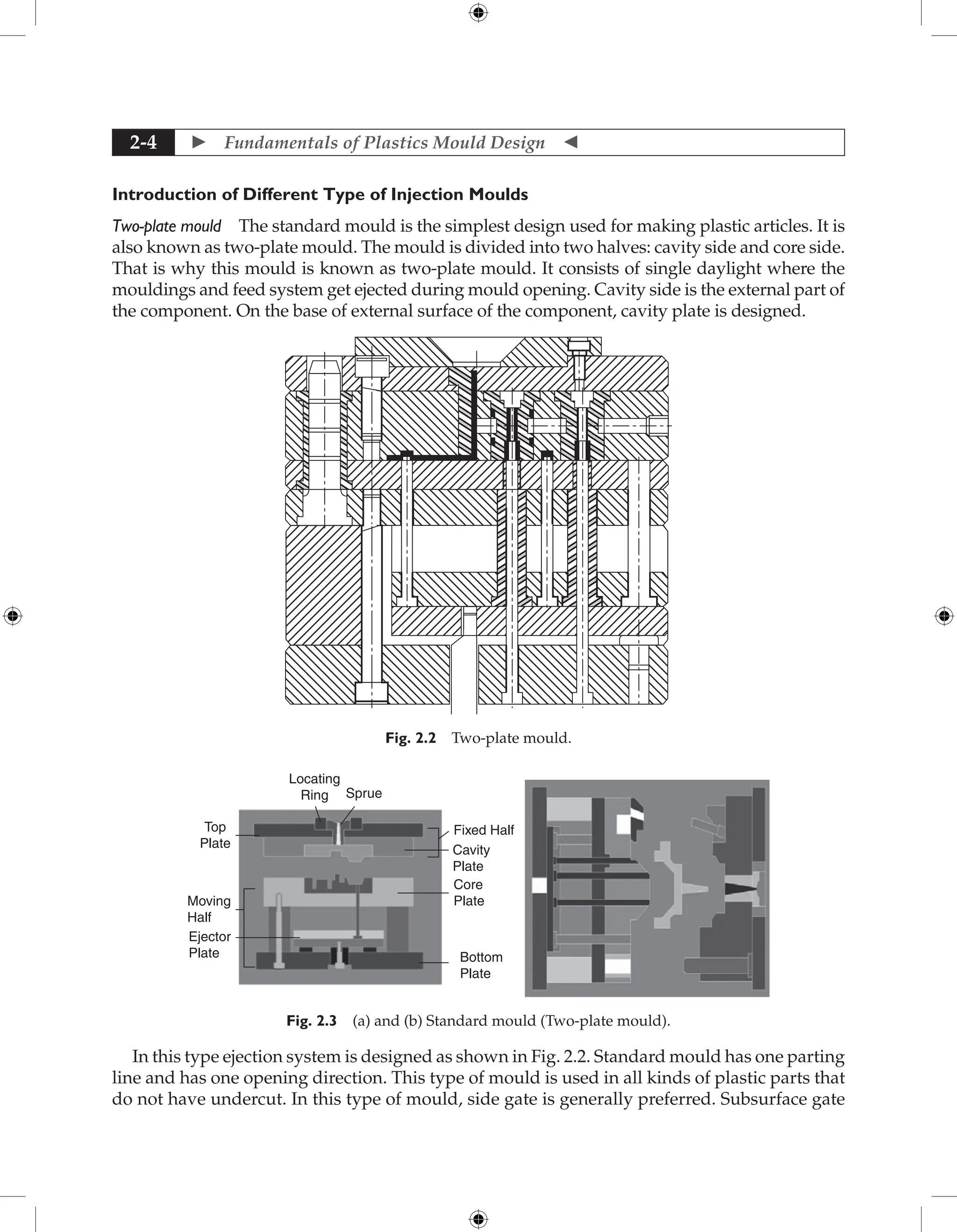

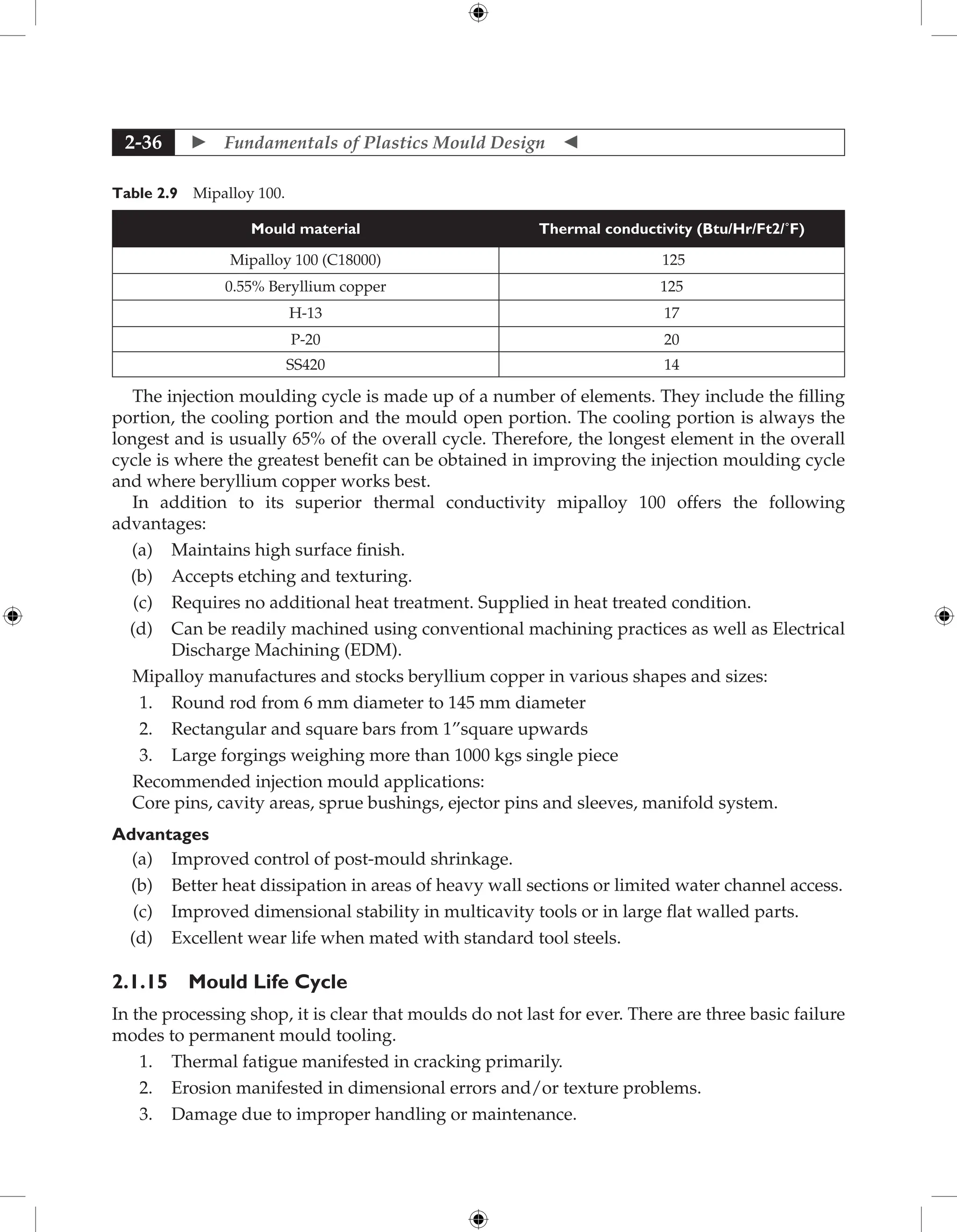

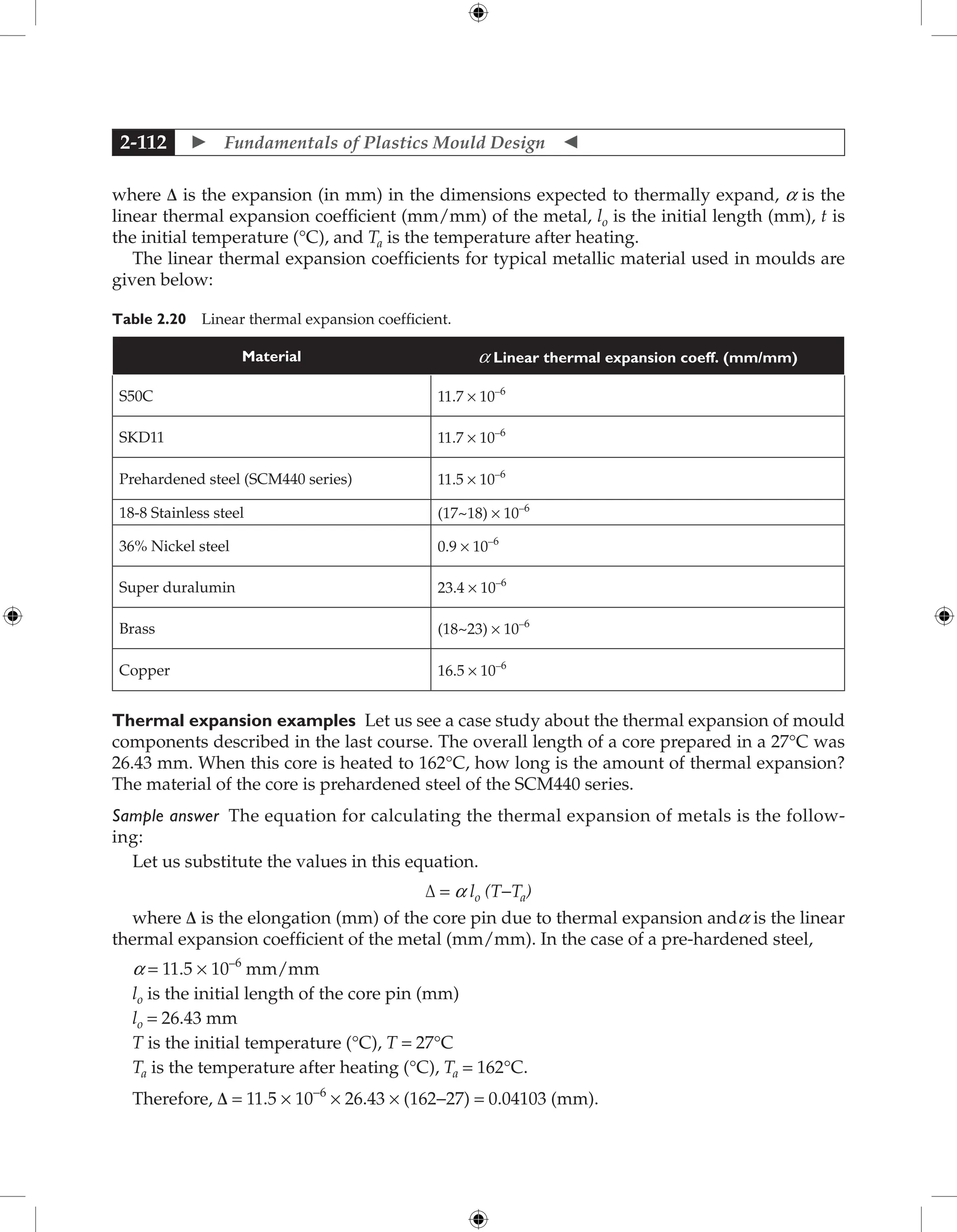

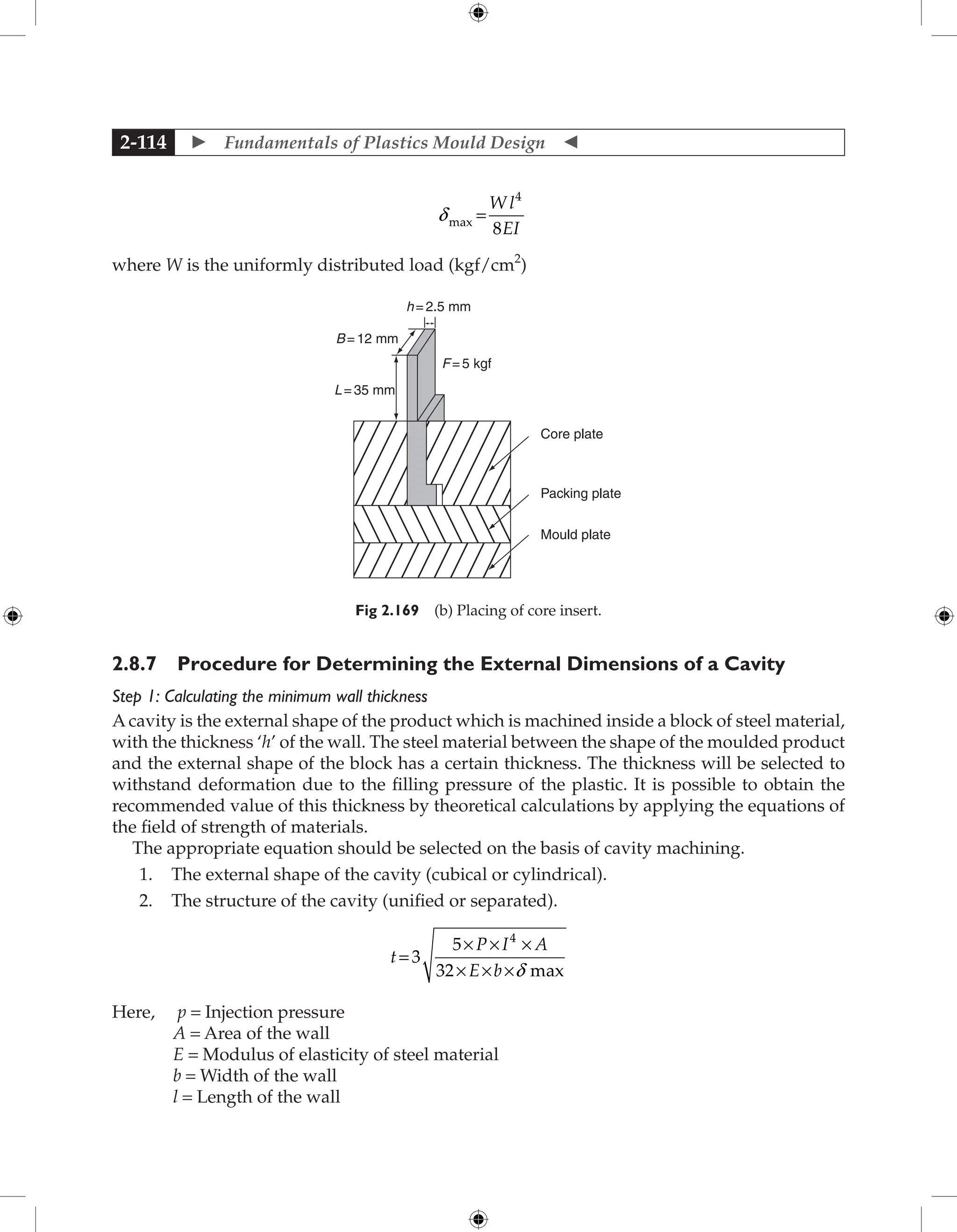

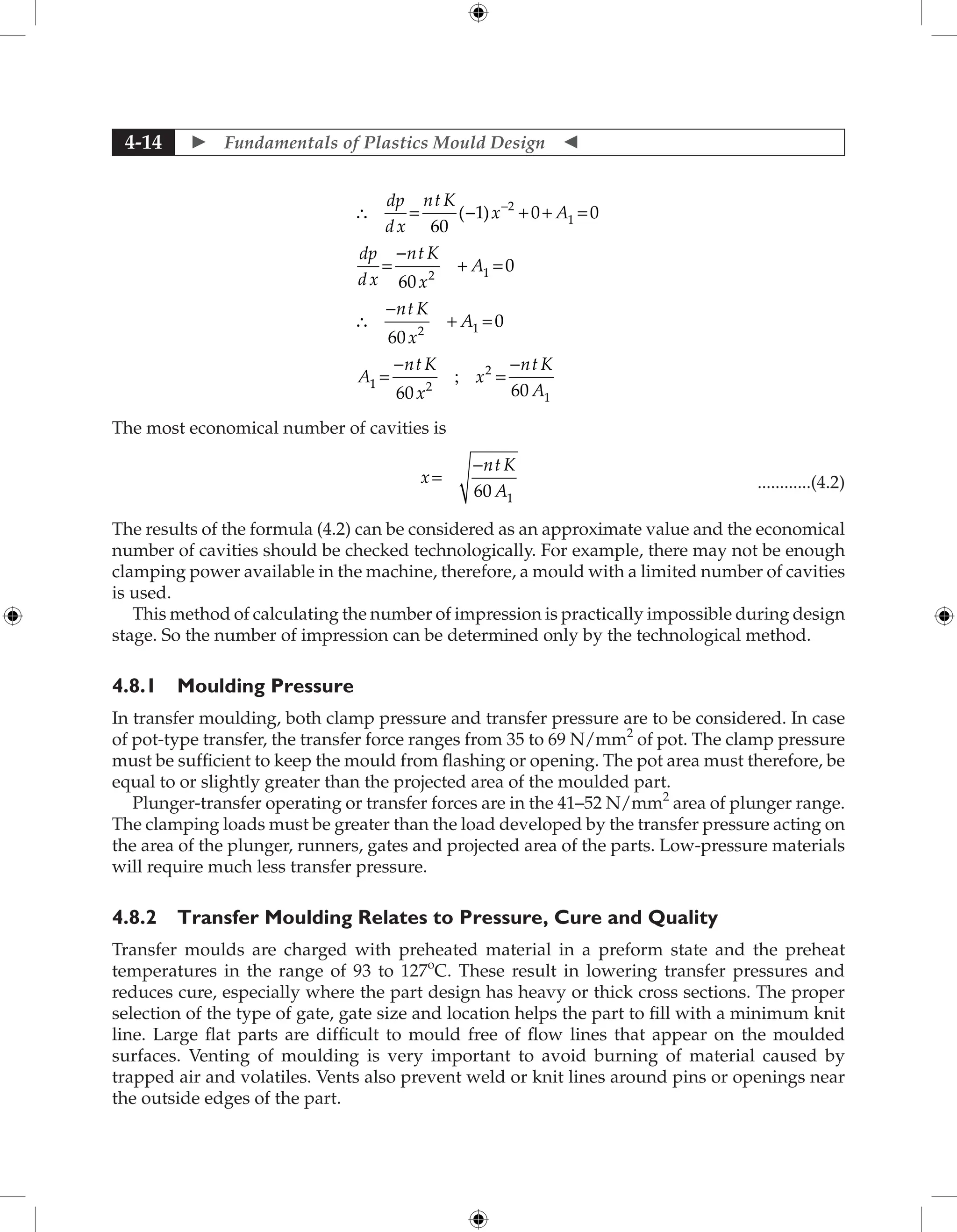

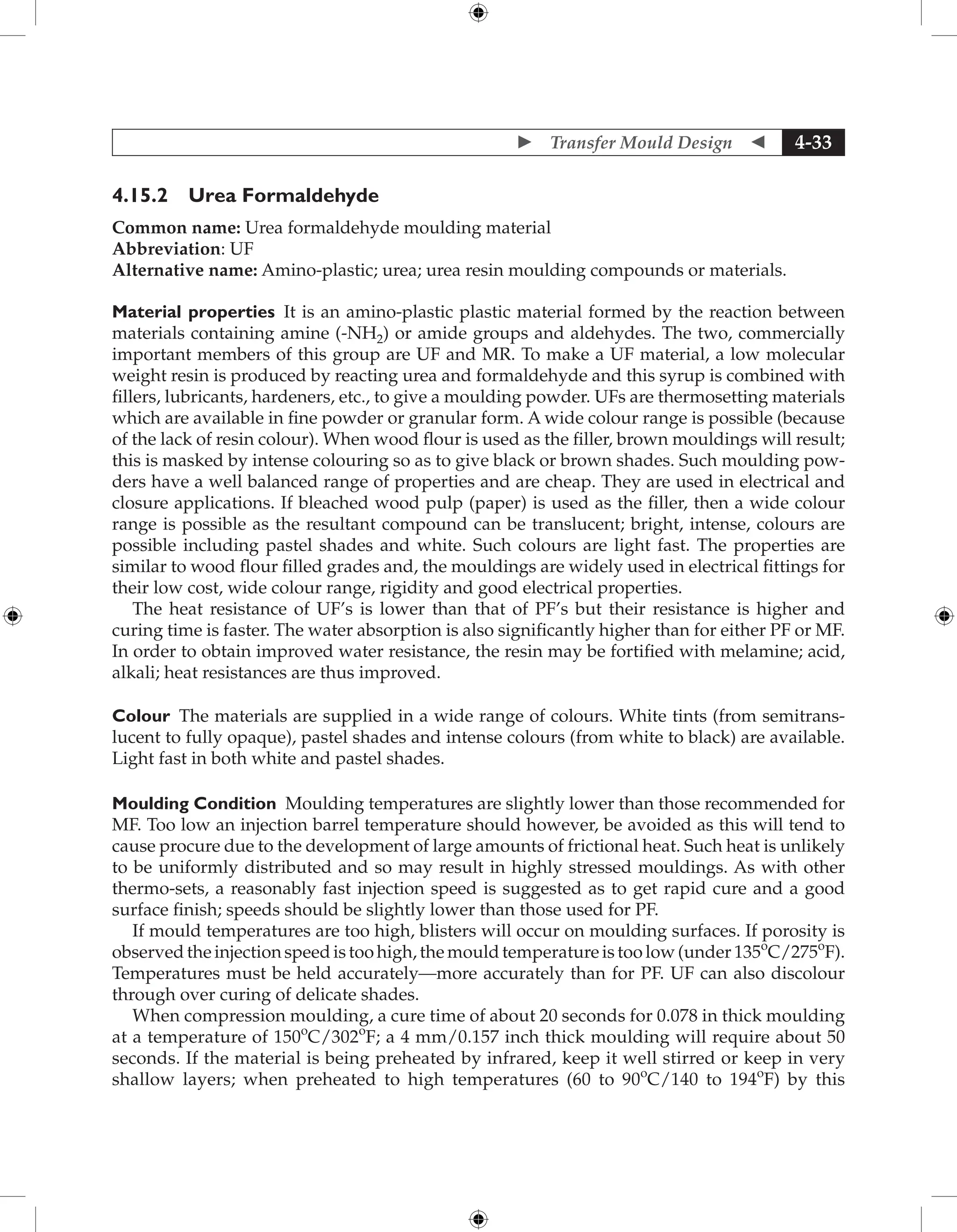

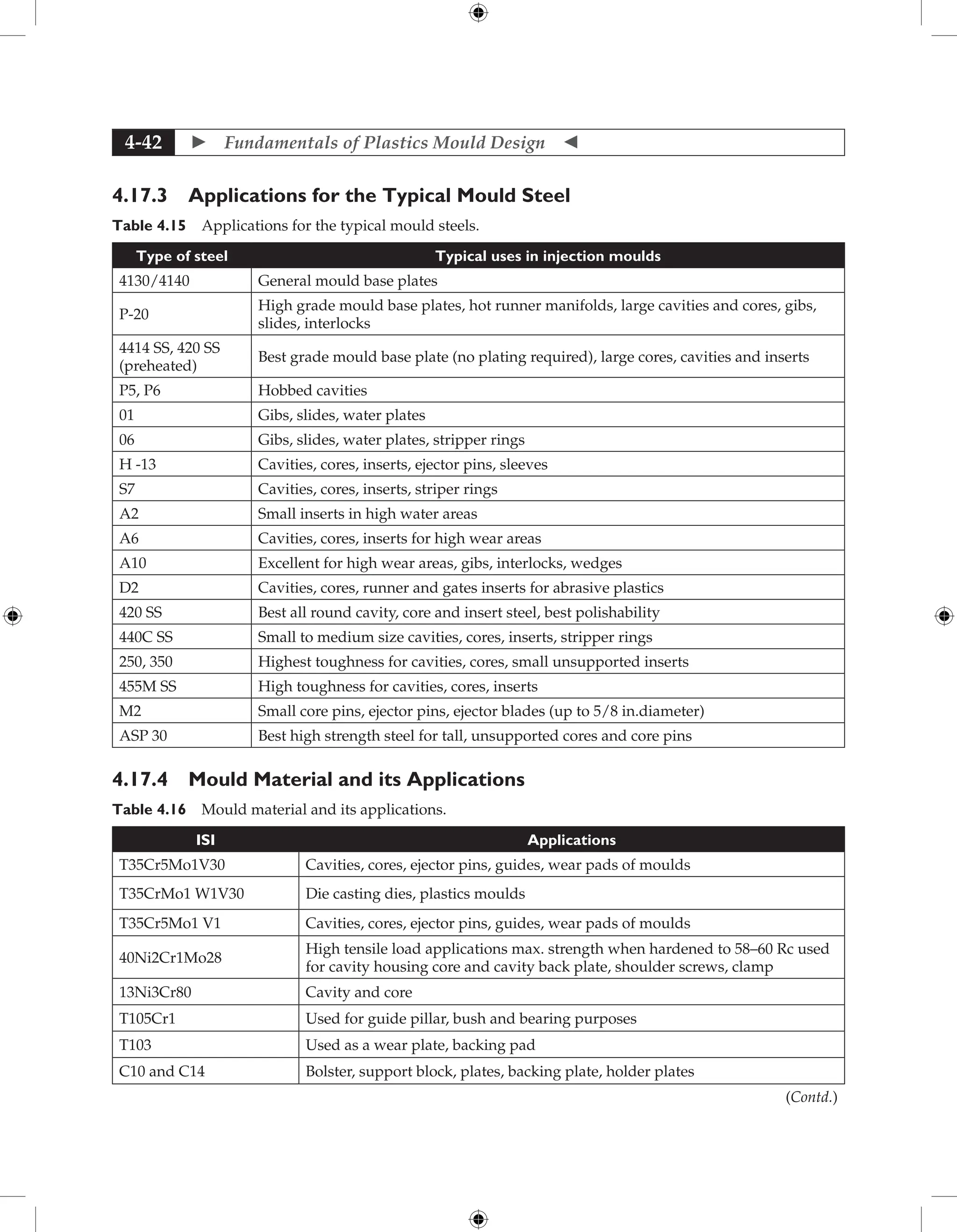

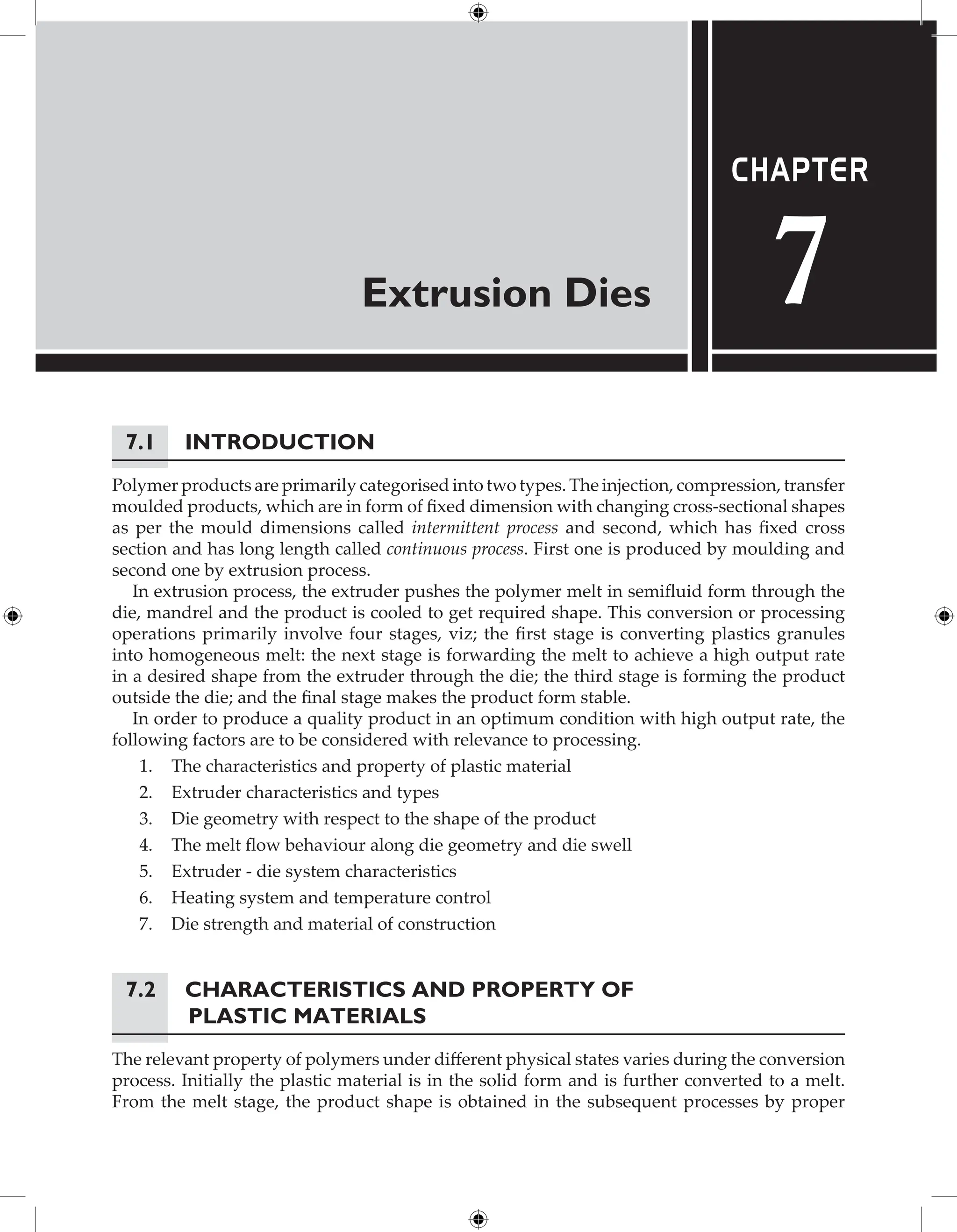

Fig. 2.115 Assembly of spacer block.

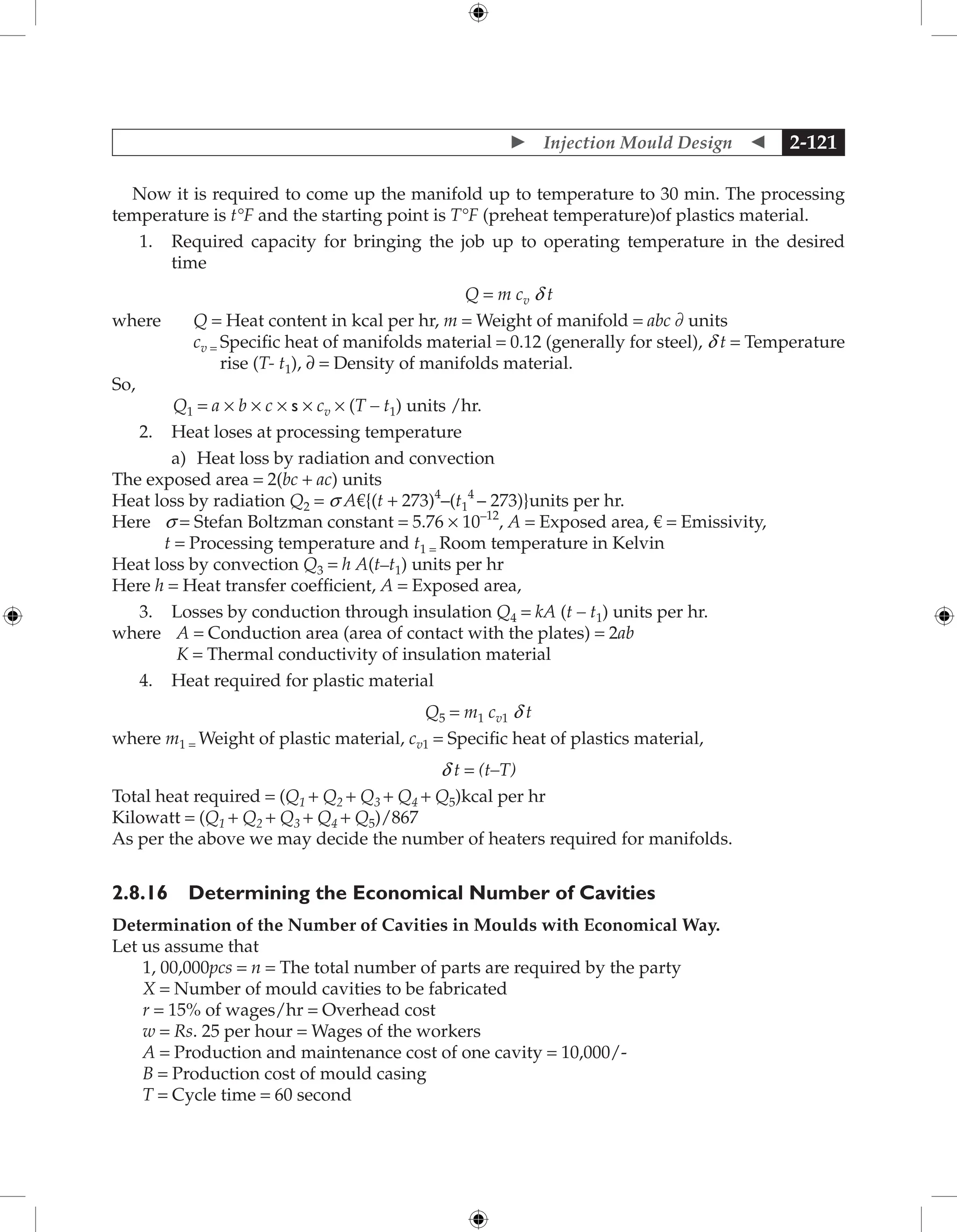

3. Frame Type Grid: It is the type of in line ejector grid except mounting of four numbers of spacer

blocks.Inthistypeofejectorgrid,completeframeismachinedoutsideandfittedwiththemounting

plate. Because of complete frame it creates one boundary for the ejection system. As per the design

of frame, the grid can be designed as rectangular, square or round type of frame ejector grid.

The main advantages of this type of ejector grid are:

(a) Good support to the back plate from all four directions.

(b) Deflection problem can be solved up to a certain level.

(c) Manufacturing cost is less.

(d) The ejection system is completely covered by one boundary, thus it prevents outside

particle to enter the system.

On the basis of shape, the frame grid is further divided as per the shape:

1. Rectangular Type: The blocks are placed as the shape of rectangle called spacer

block.

2. Square Type: The frame is machined as the shape of square called square type grid.

3. Round Type: The blocks are machined in the round shape or well type called round

type grid.

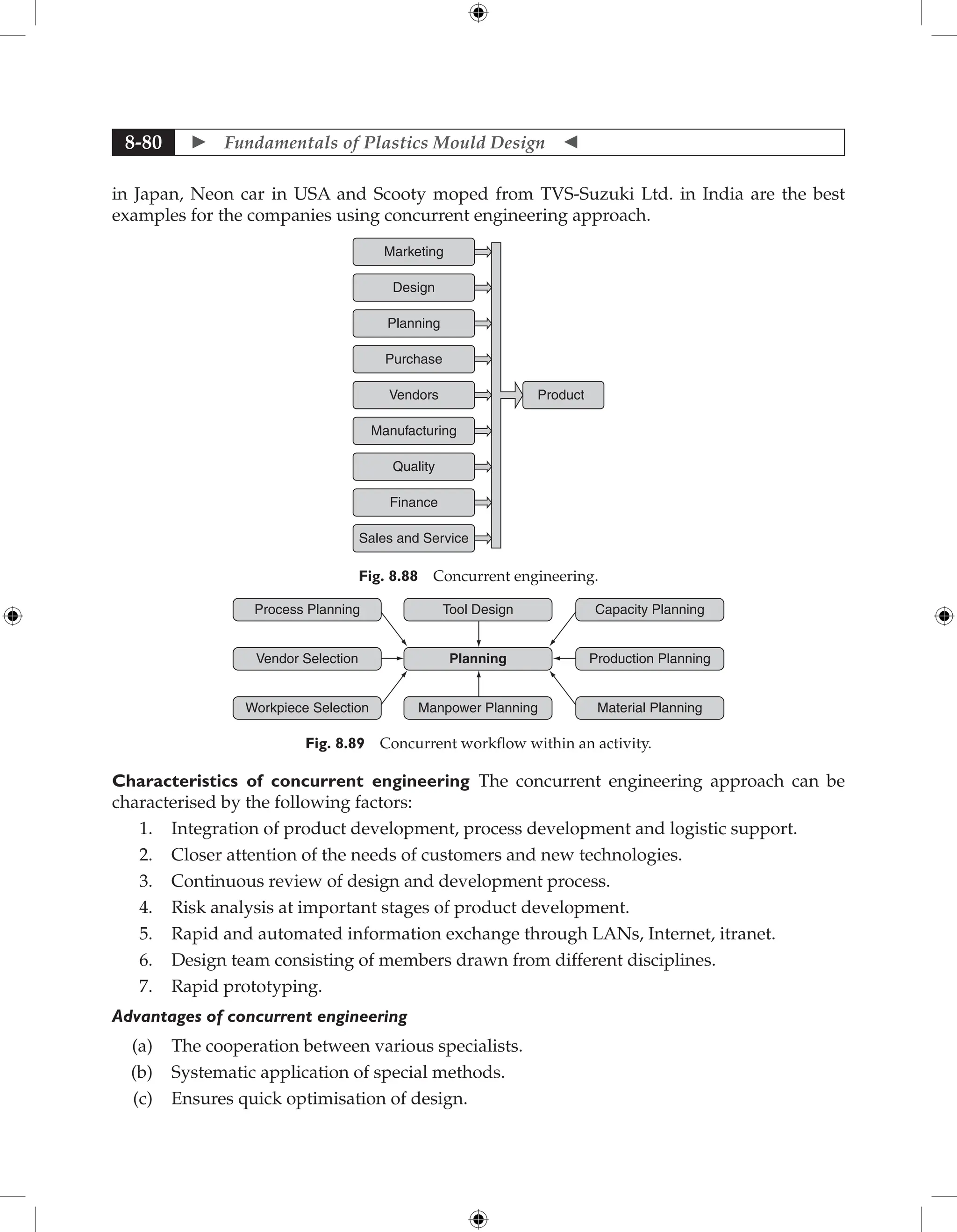

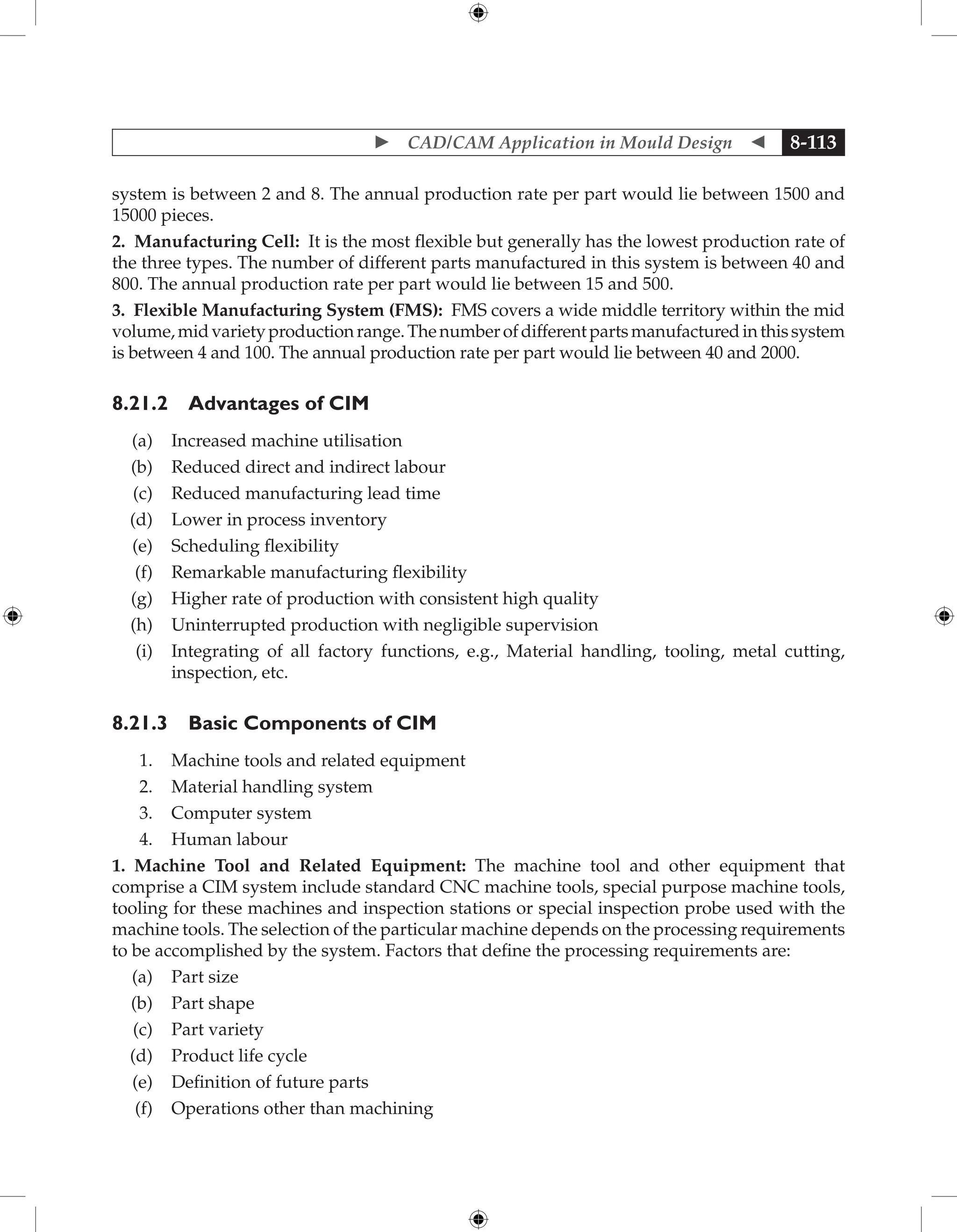

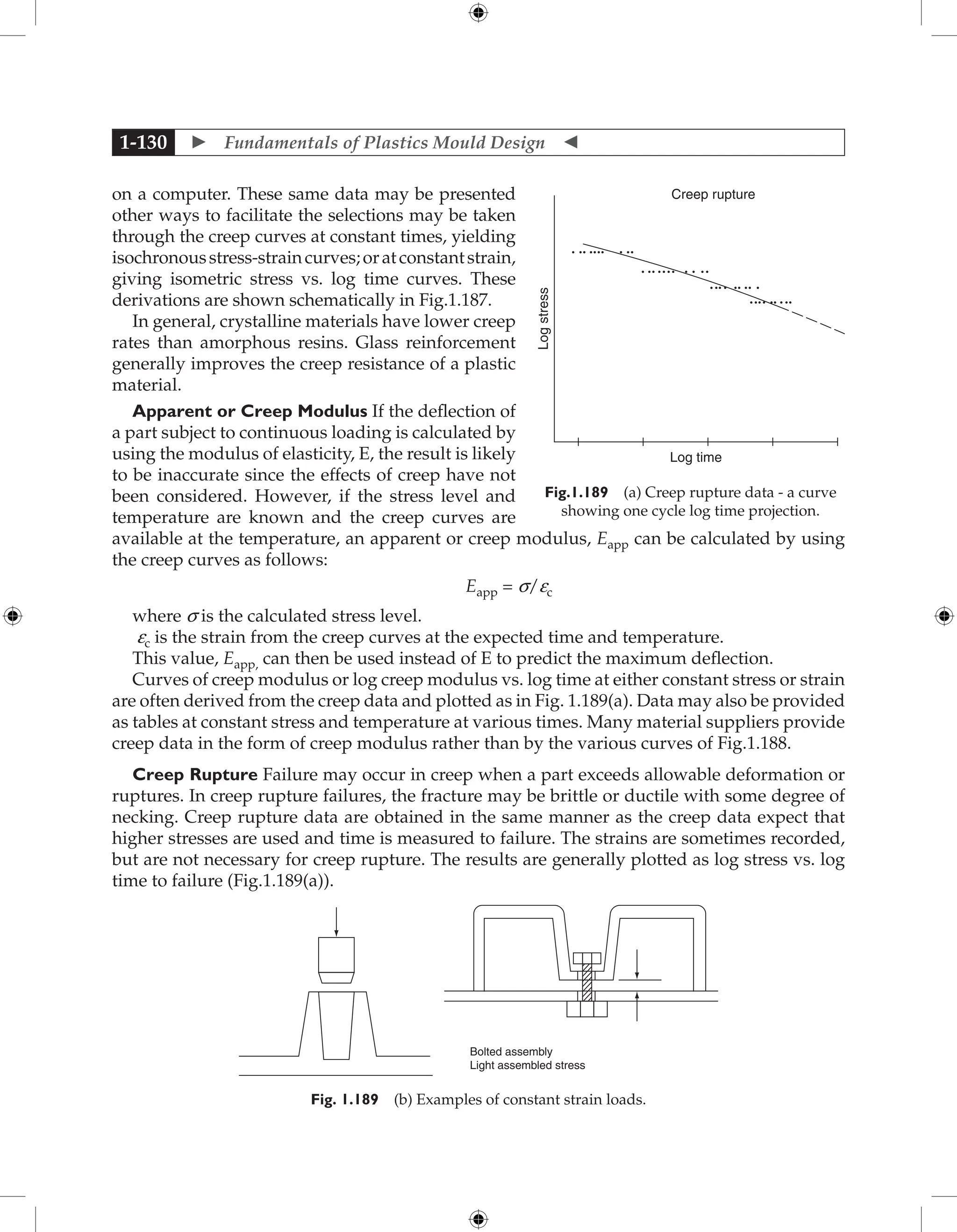

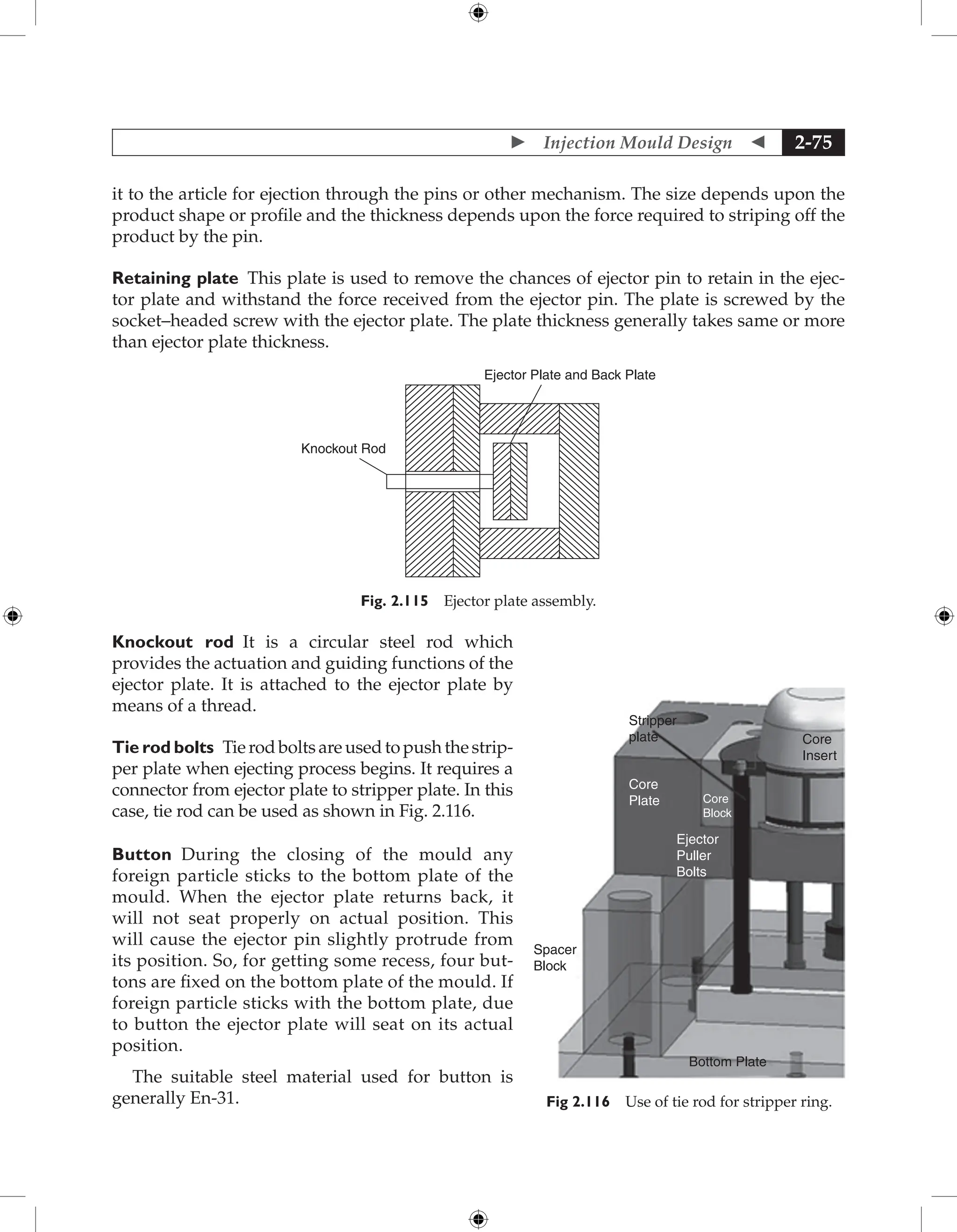

2.6.2 Ejector Plate Assembly

It is that part of the mould to which the ejector element is fitted. It normally consists of an

ejector plate, retaining plate and ejector rod as shown in Fig. 2.115.

Ejector plate It is a steel plate in which the ejector system like ejector [pin, valve, step pin] is

incorporated. The force is applied from the machine moving half to this plate for transmitting](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fundamentalsofmoulddesign-231217032858-869d3d7e/75/Fundamentals-of-Mould-Design-lecture-pdf-269-2048.jpg)

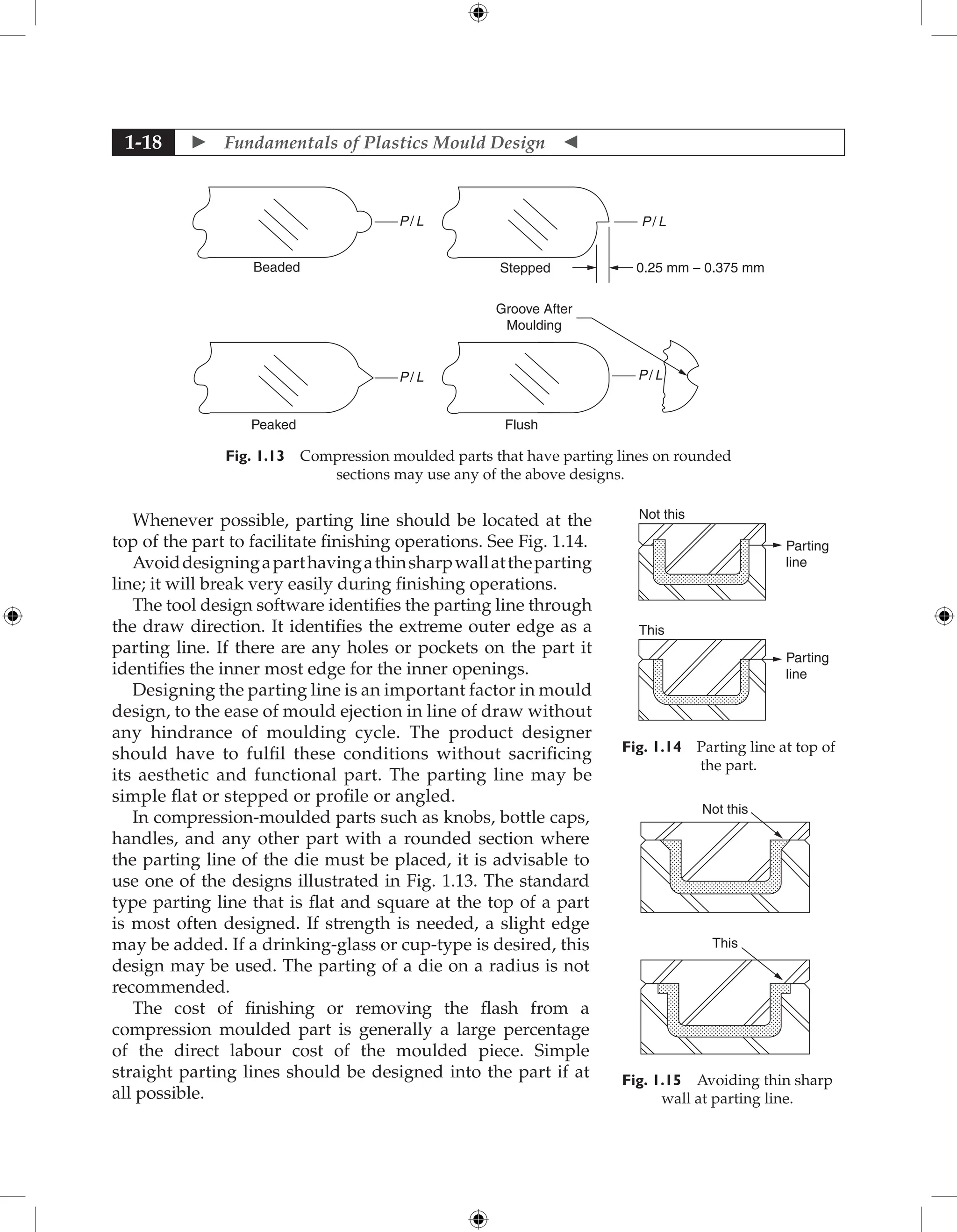

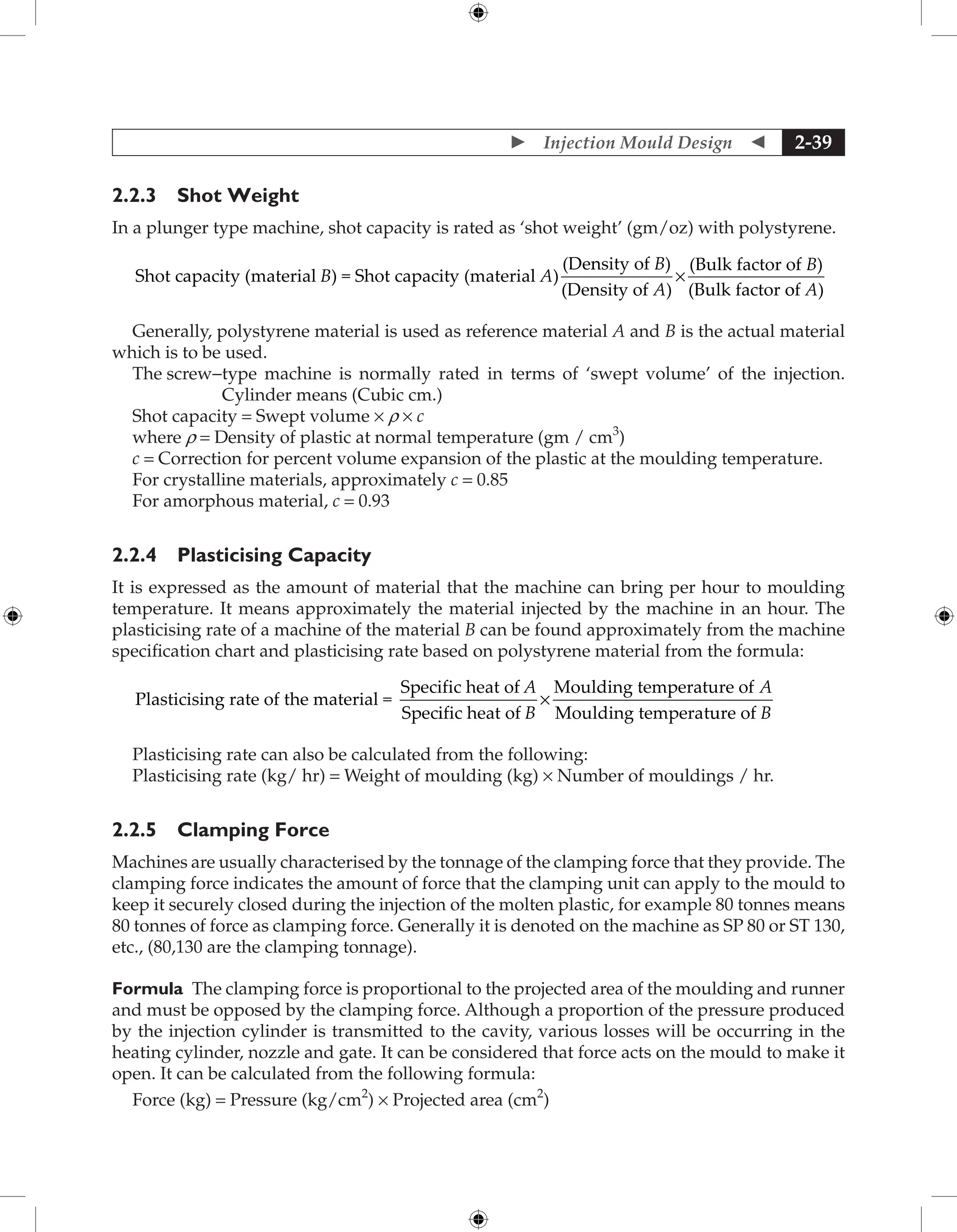

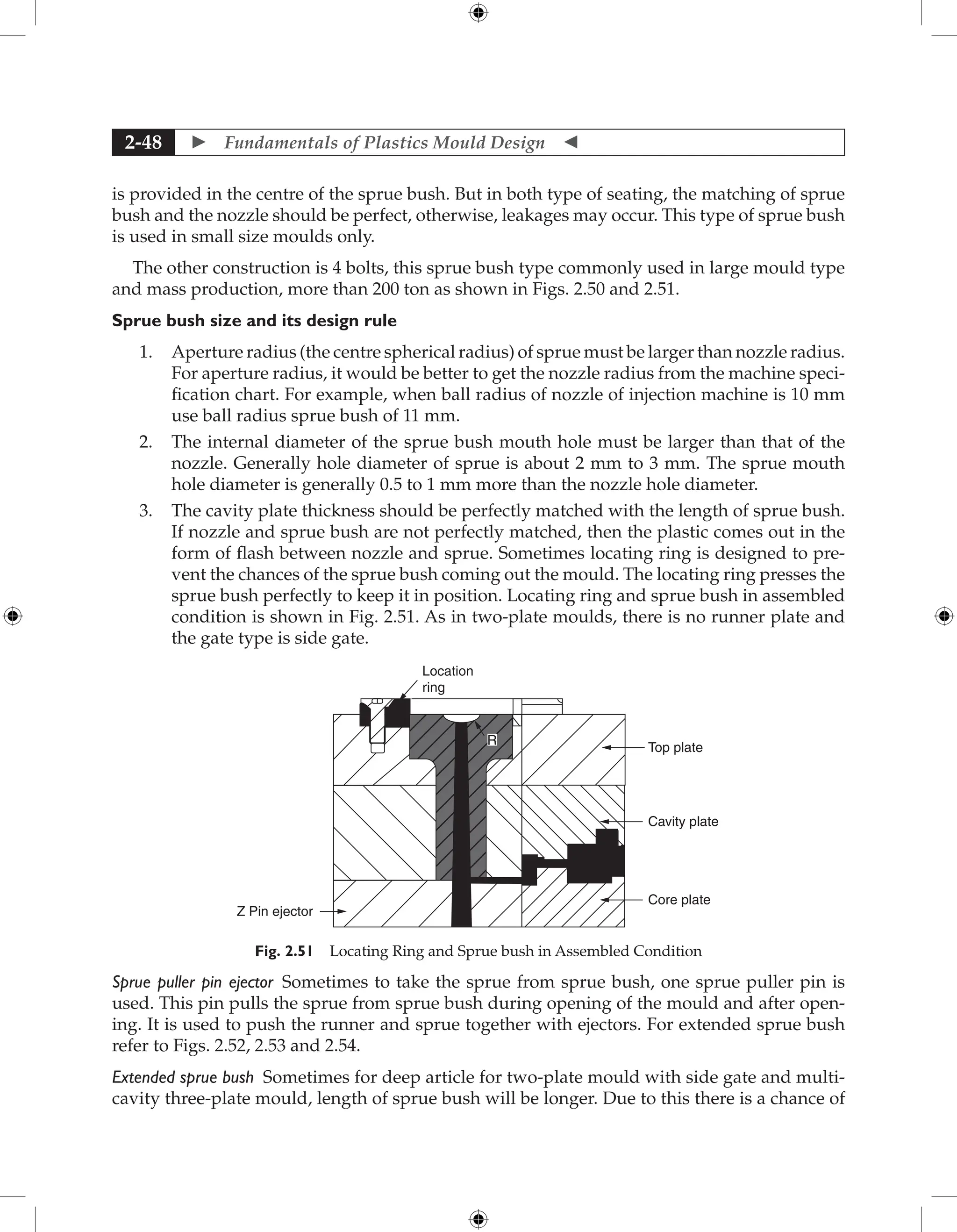

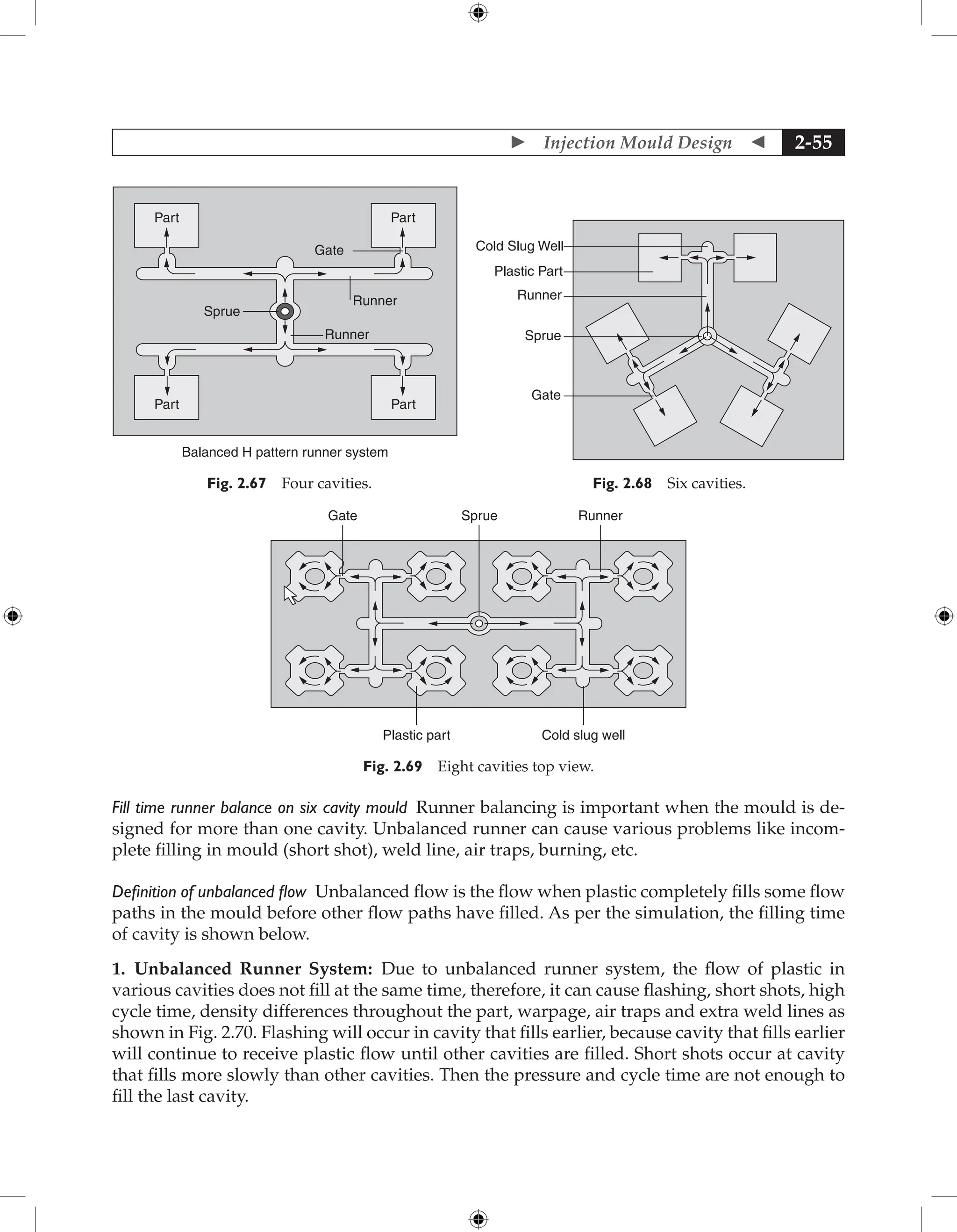

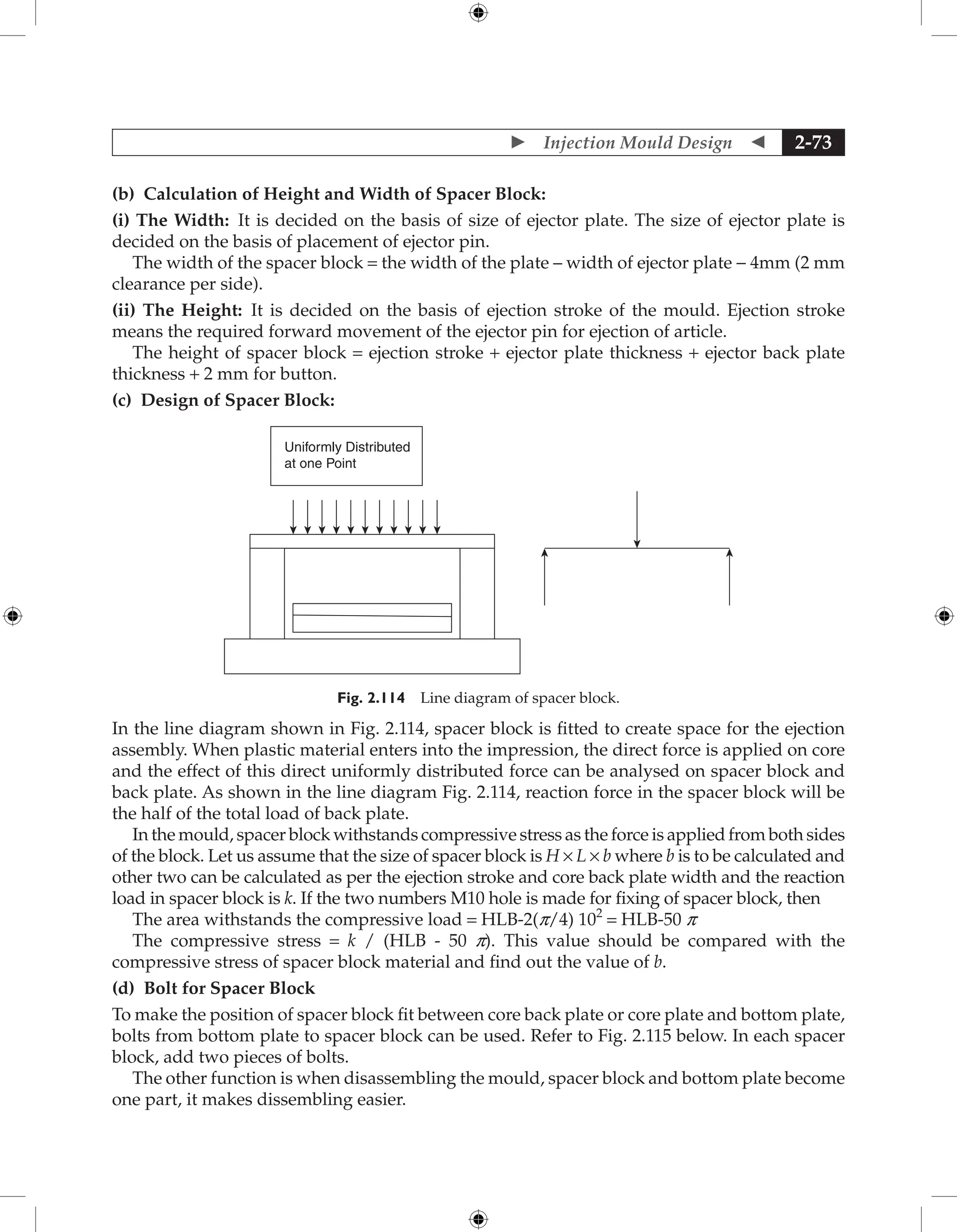

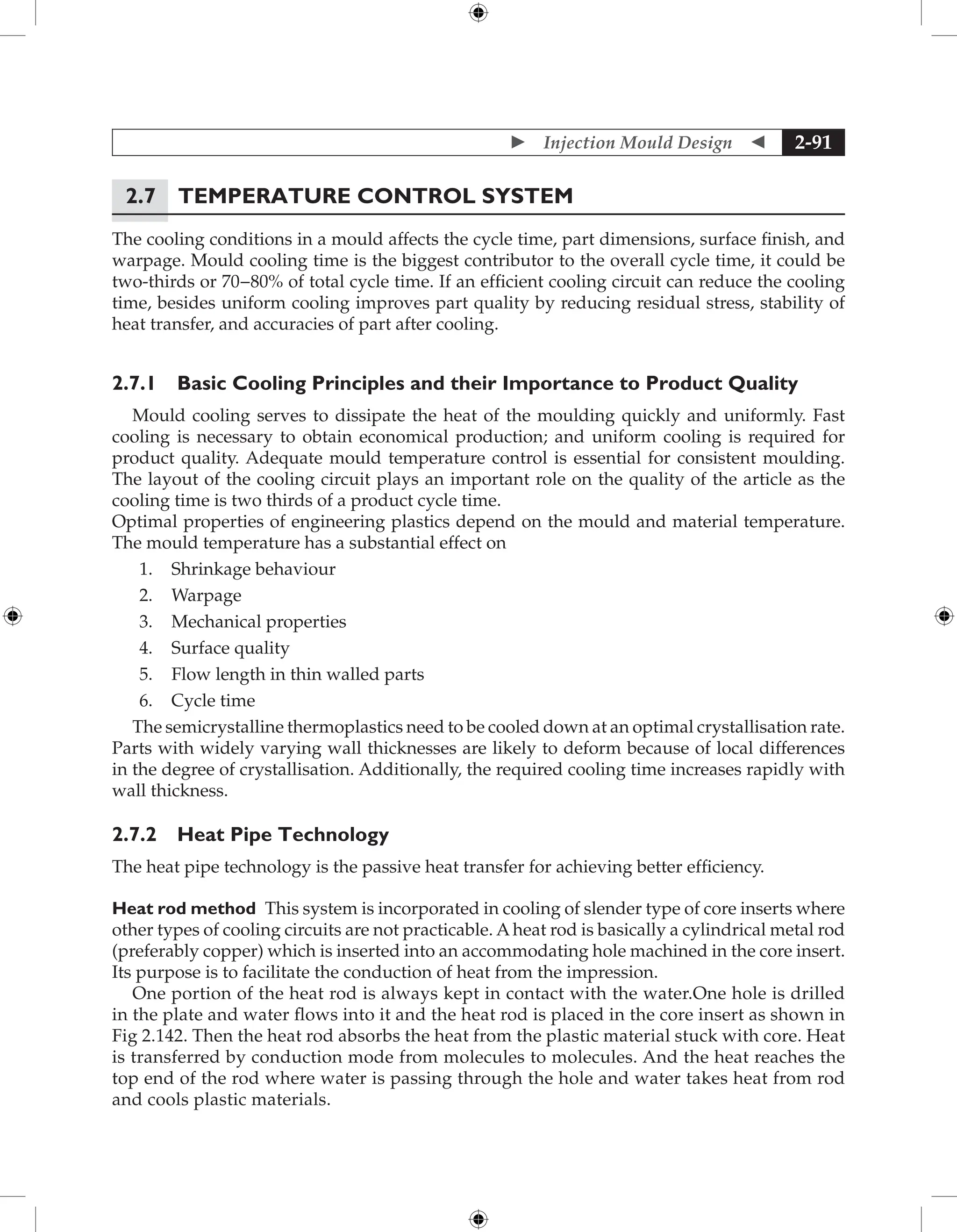

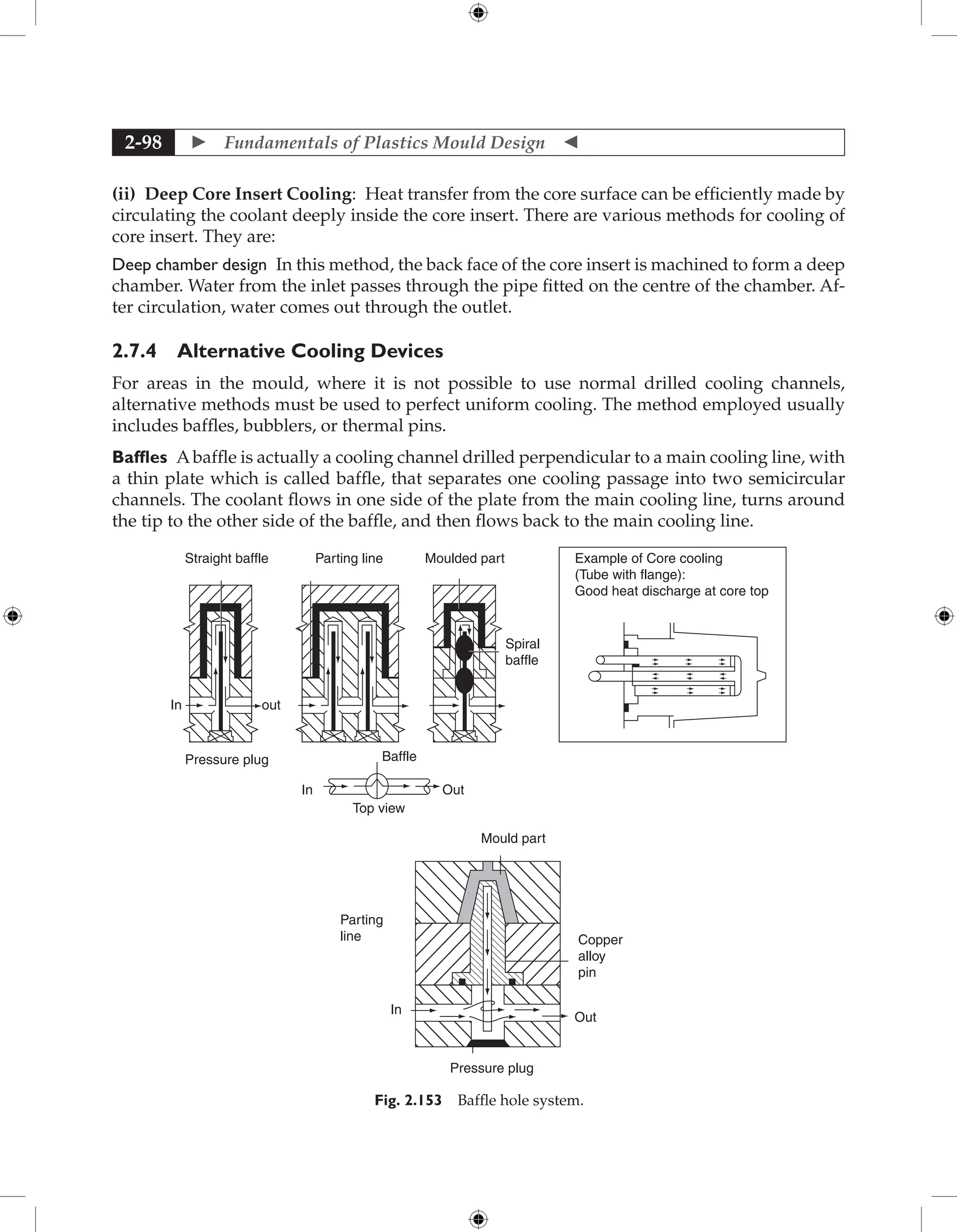

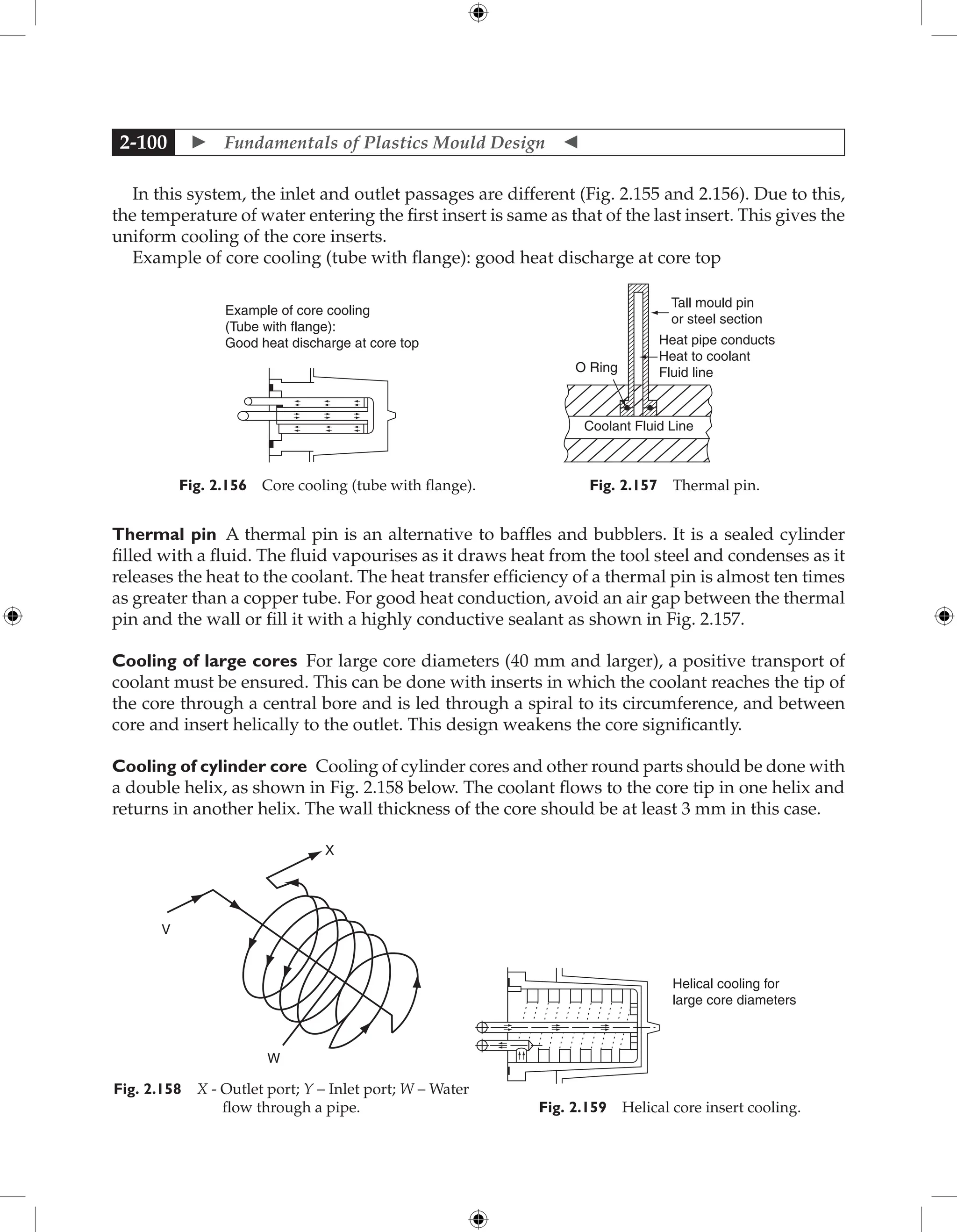

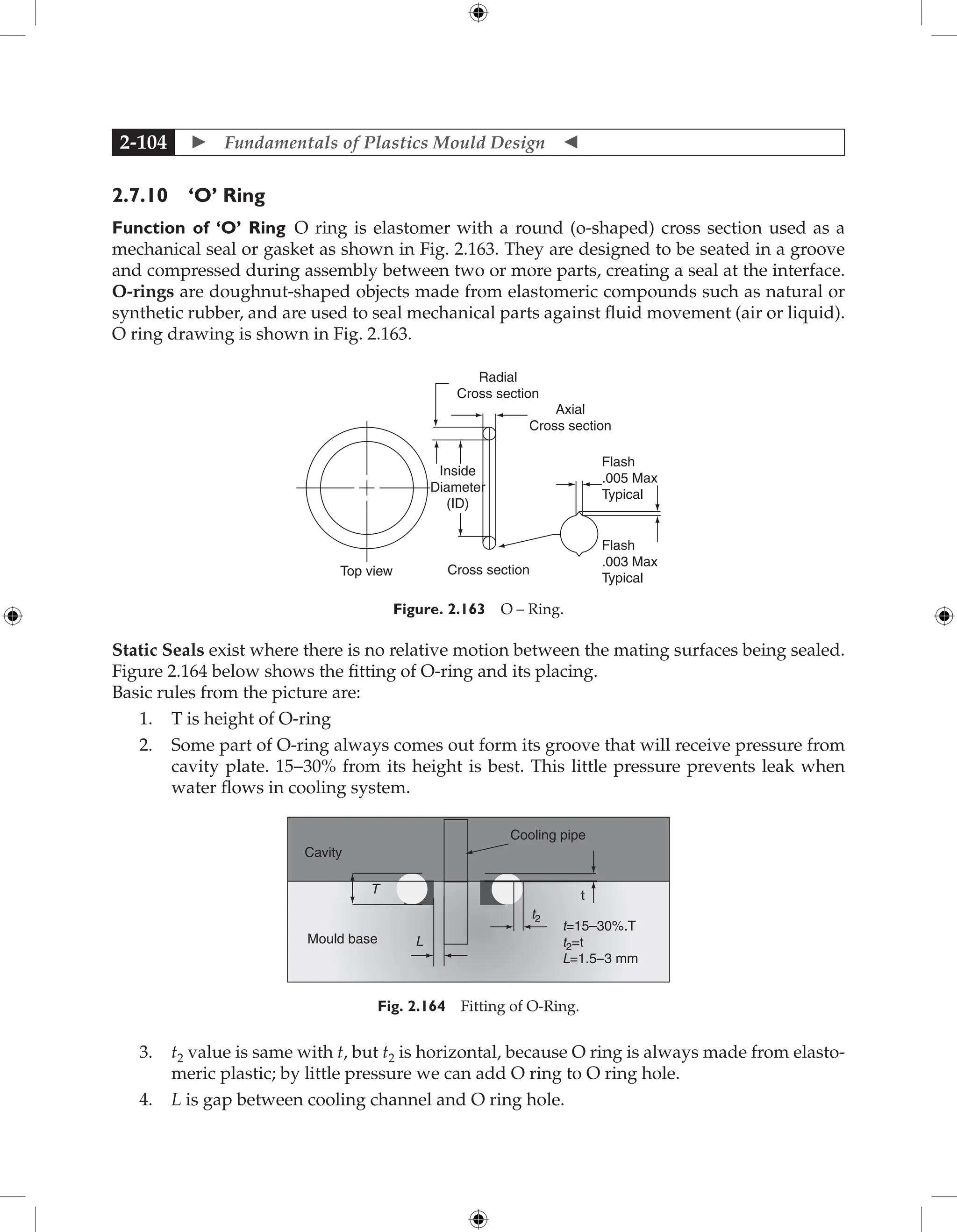

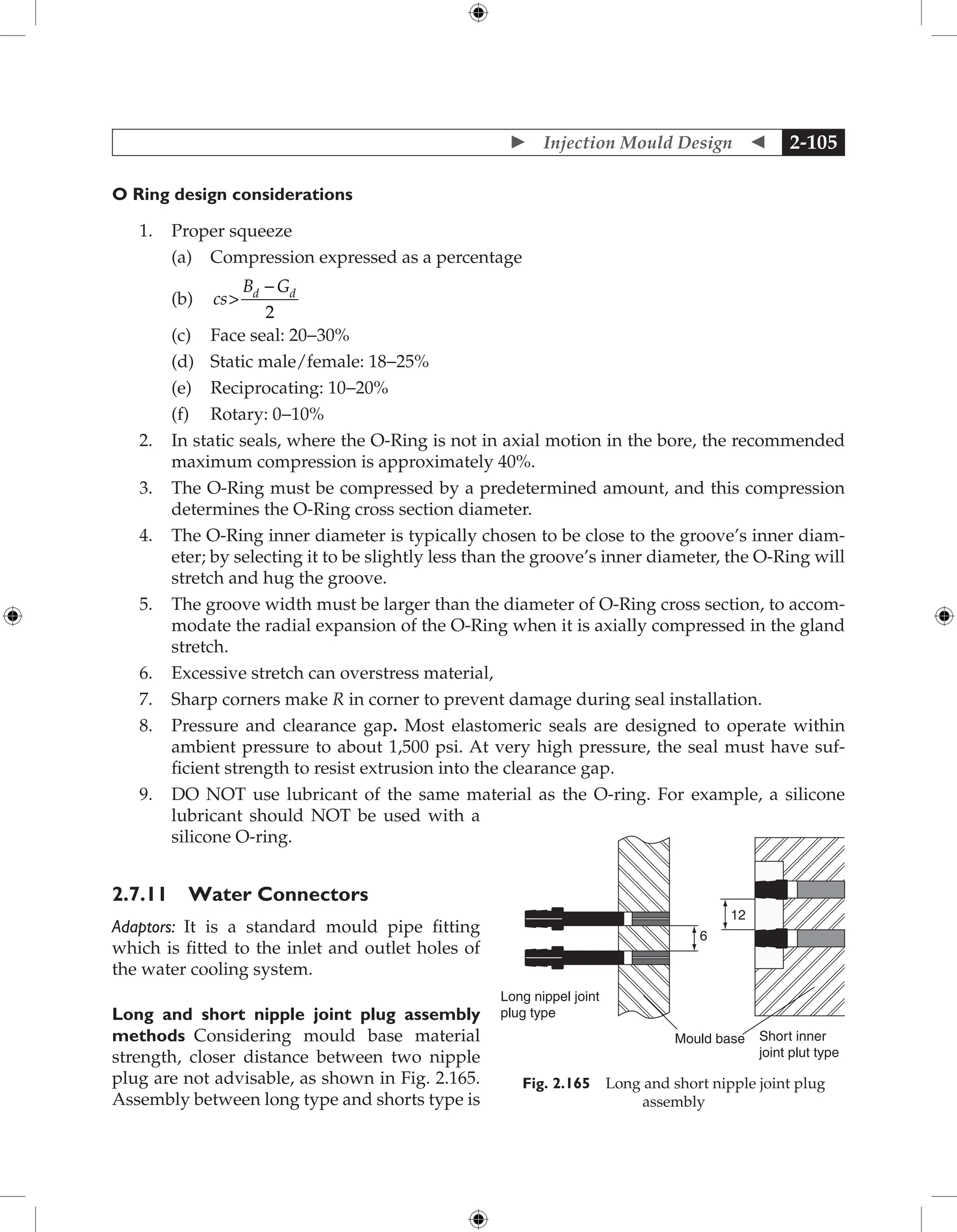

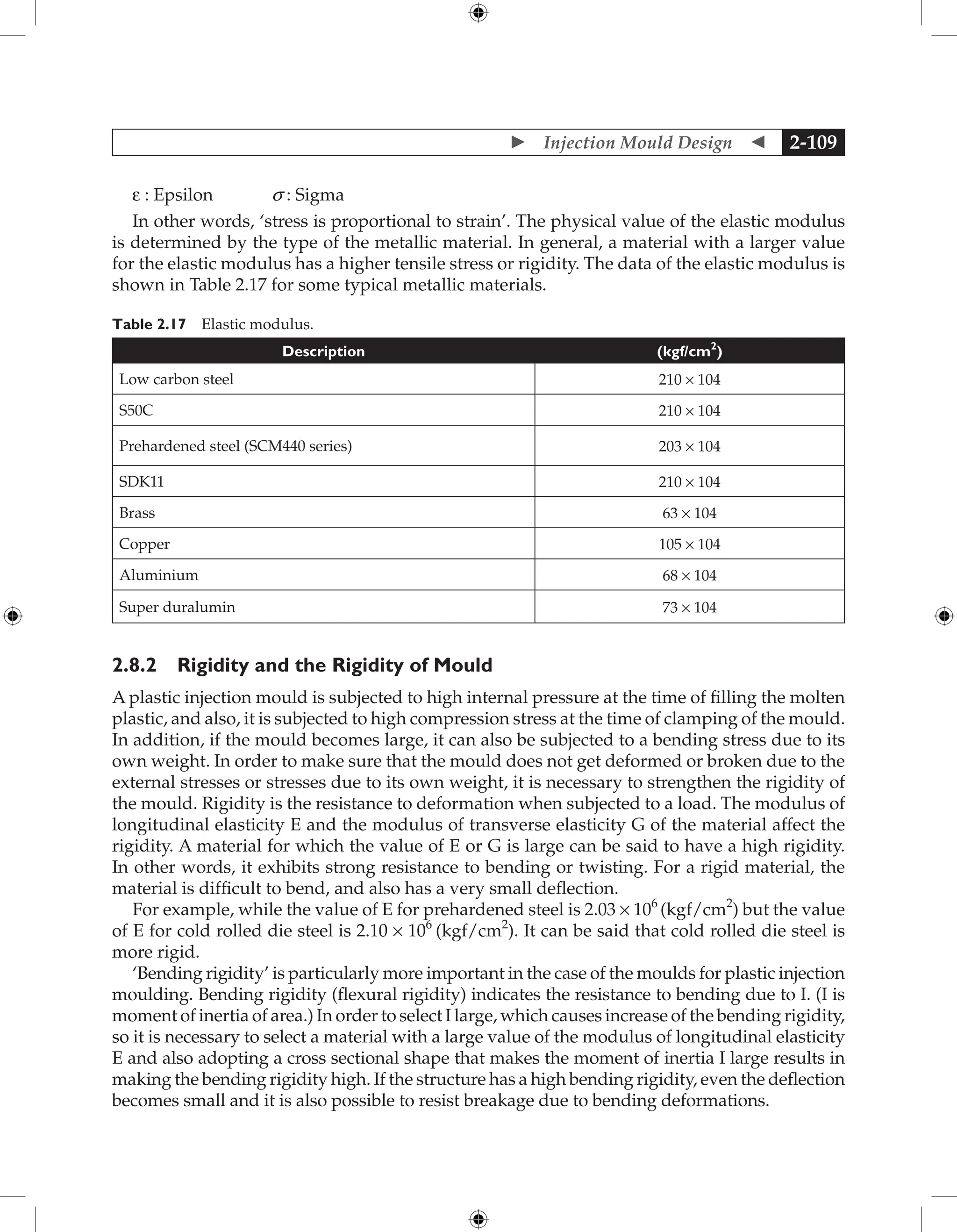

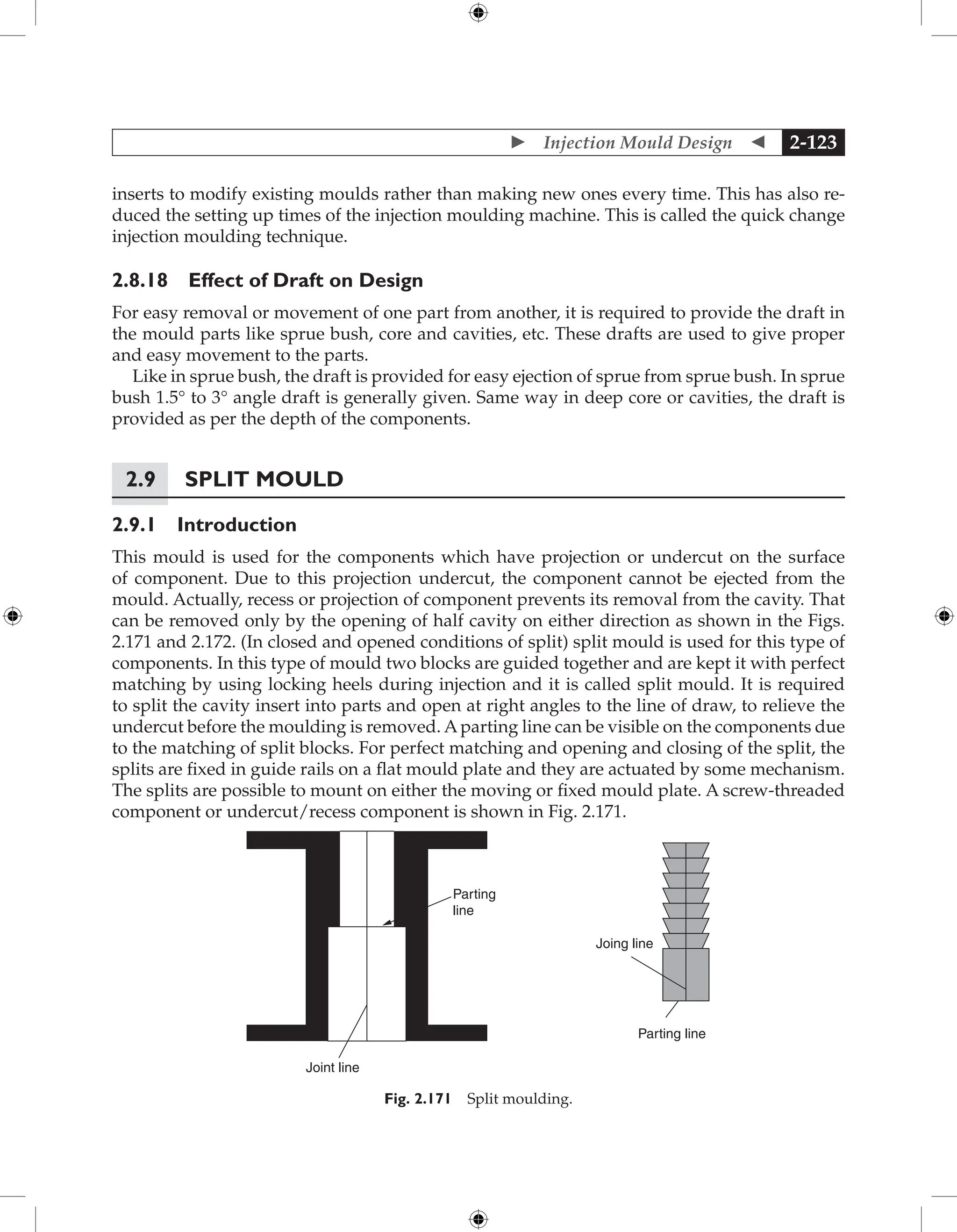

![ Injection Mould Design 2-101

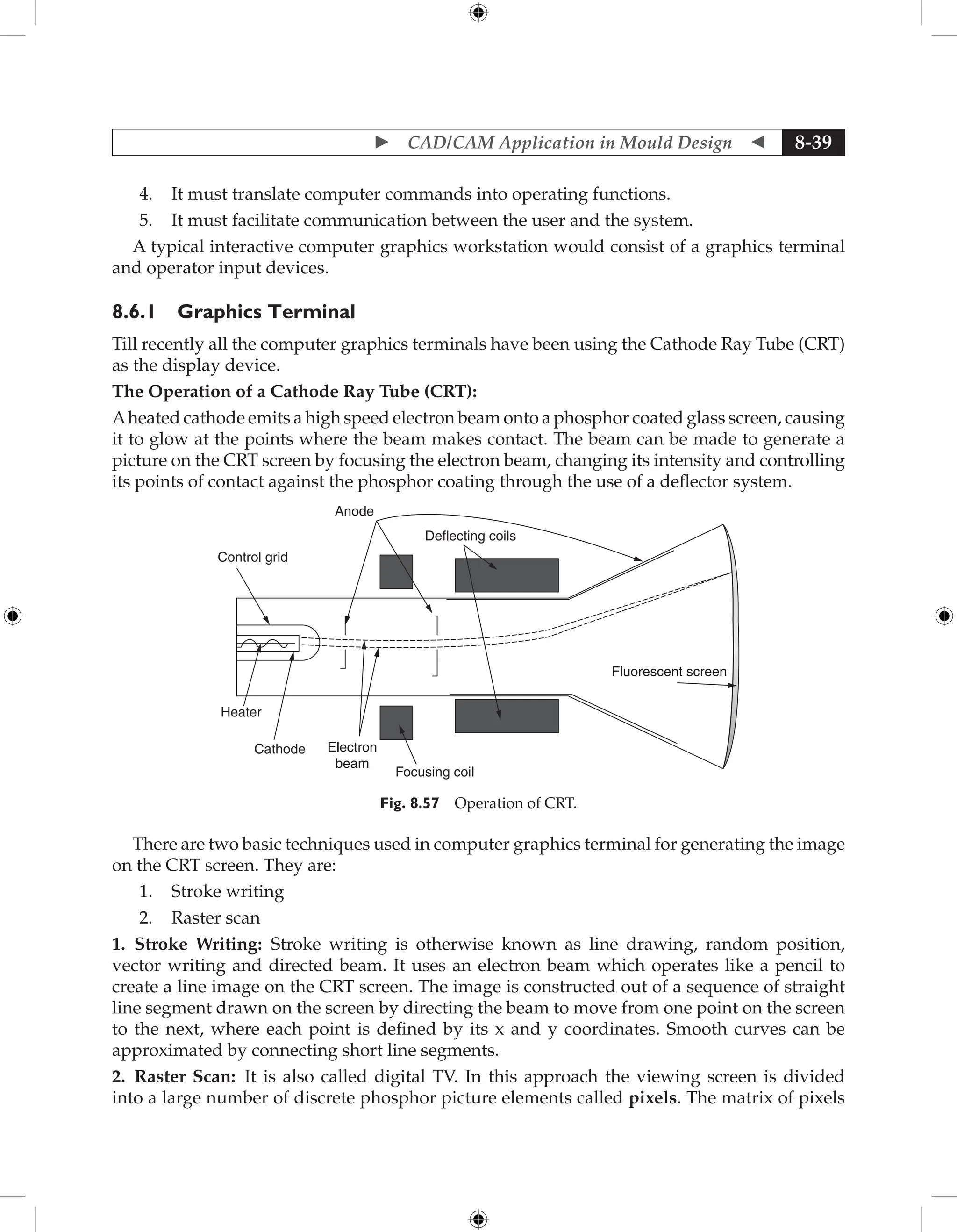

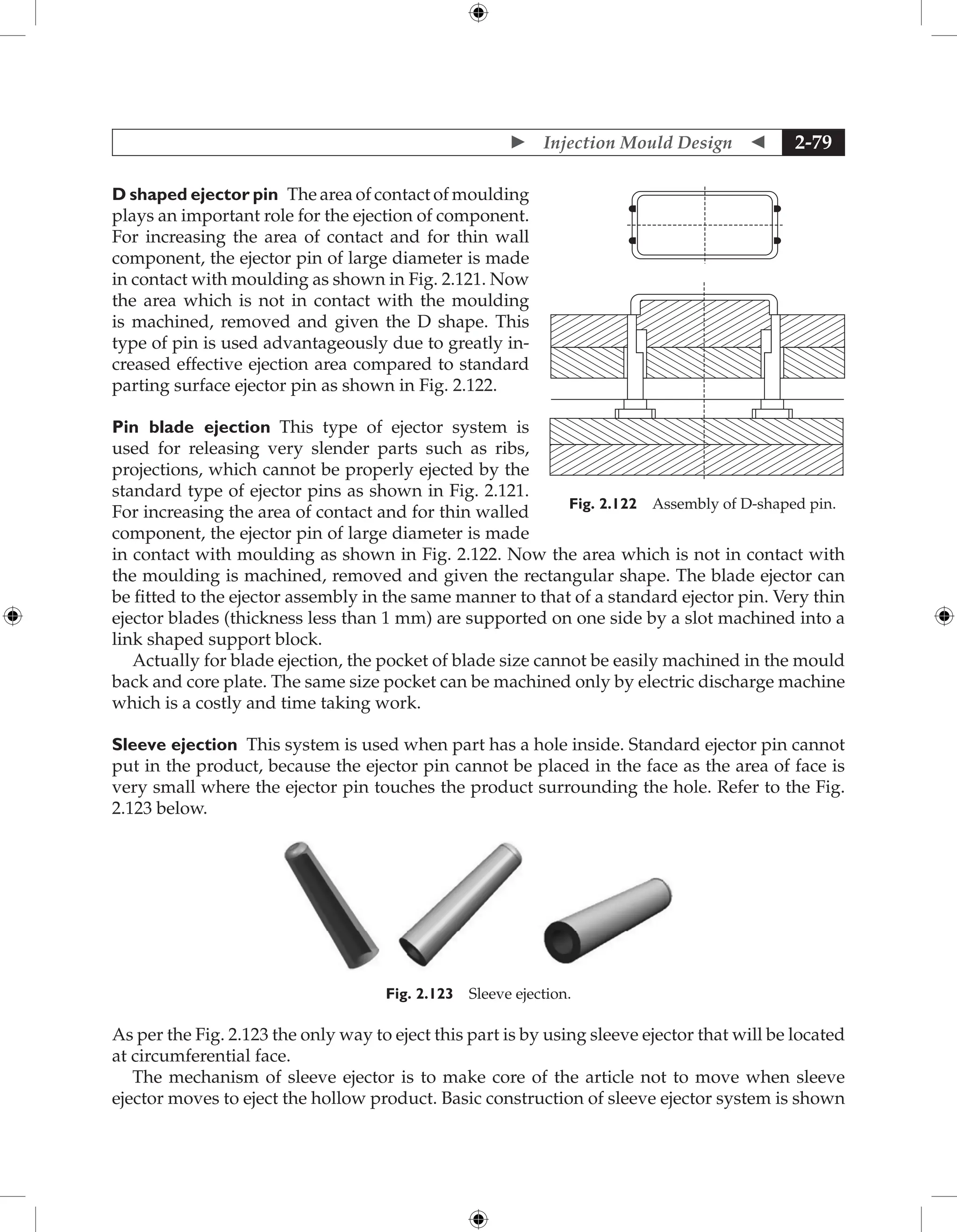

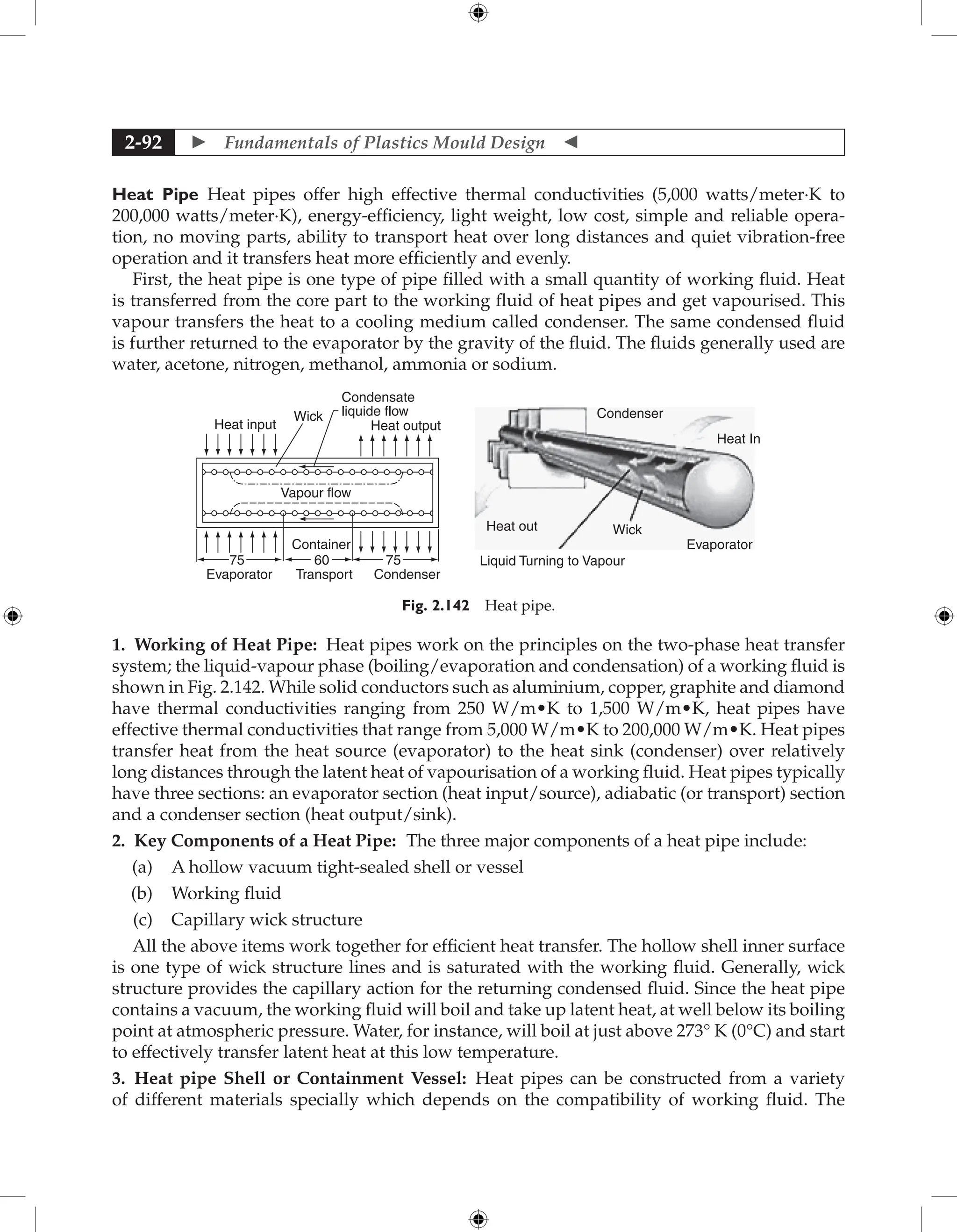

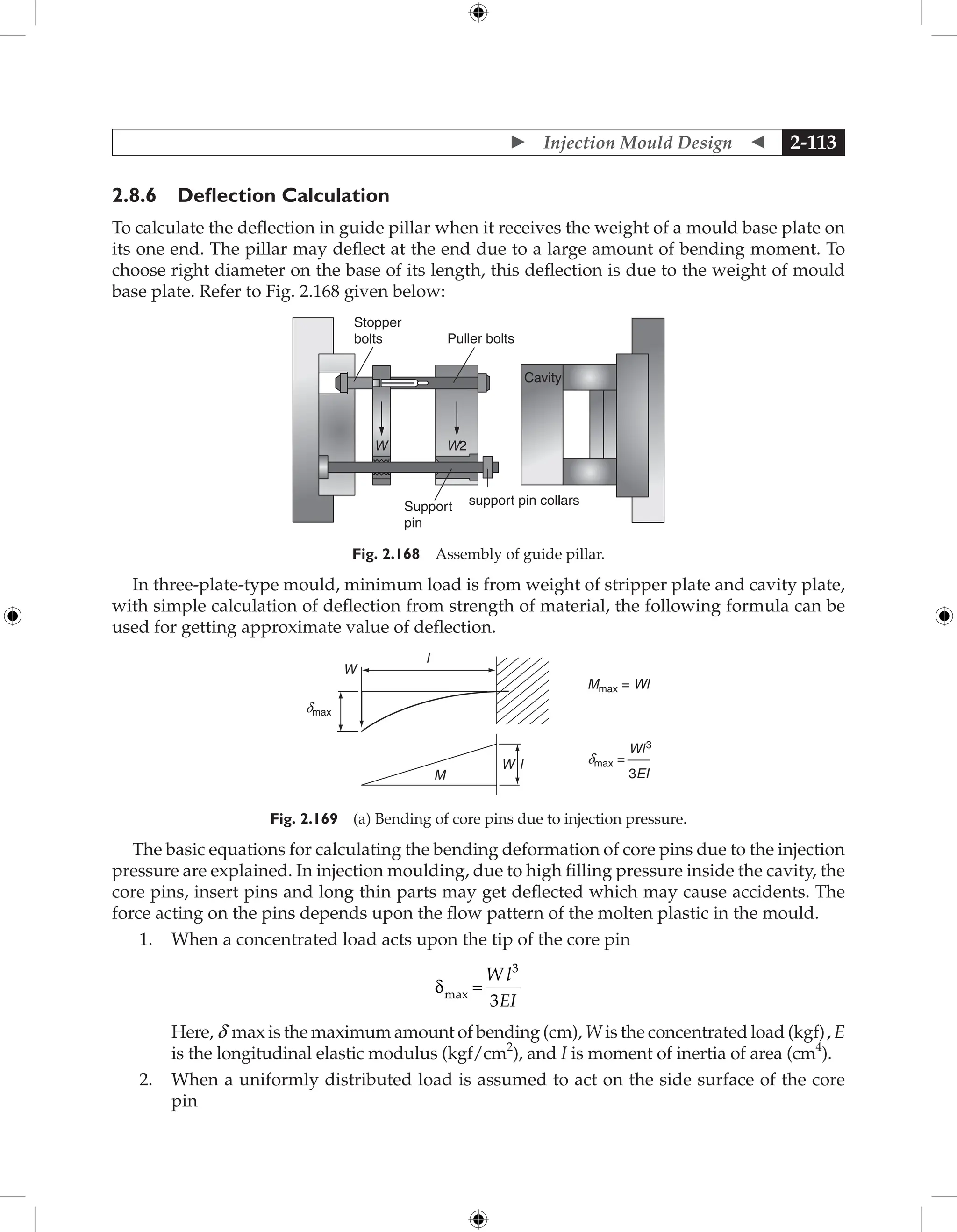

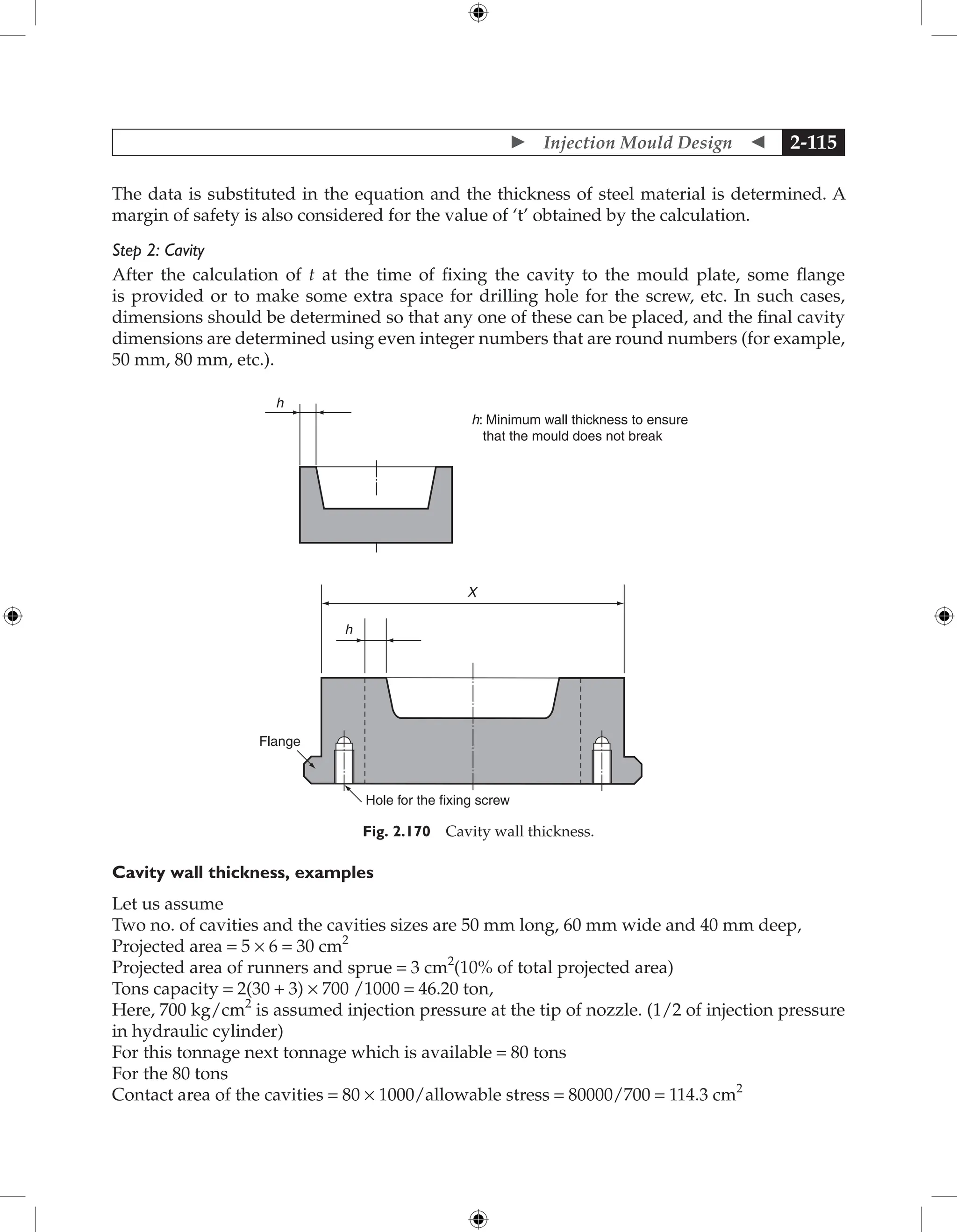

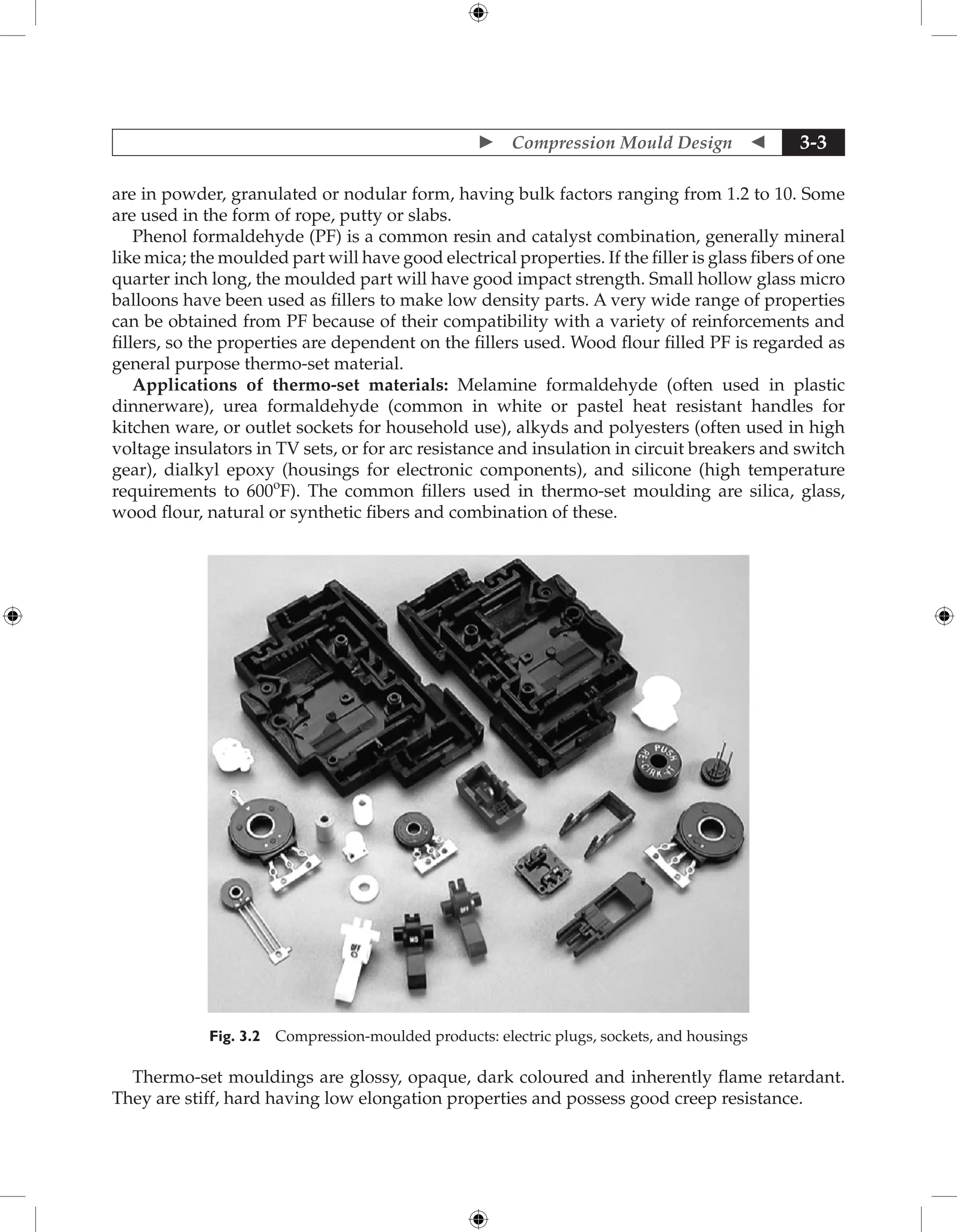

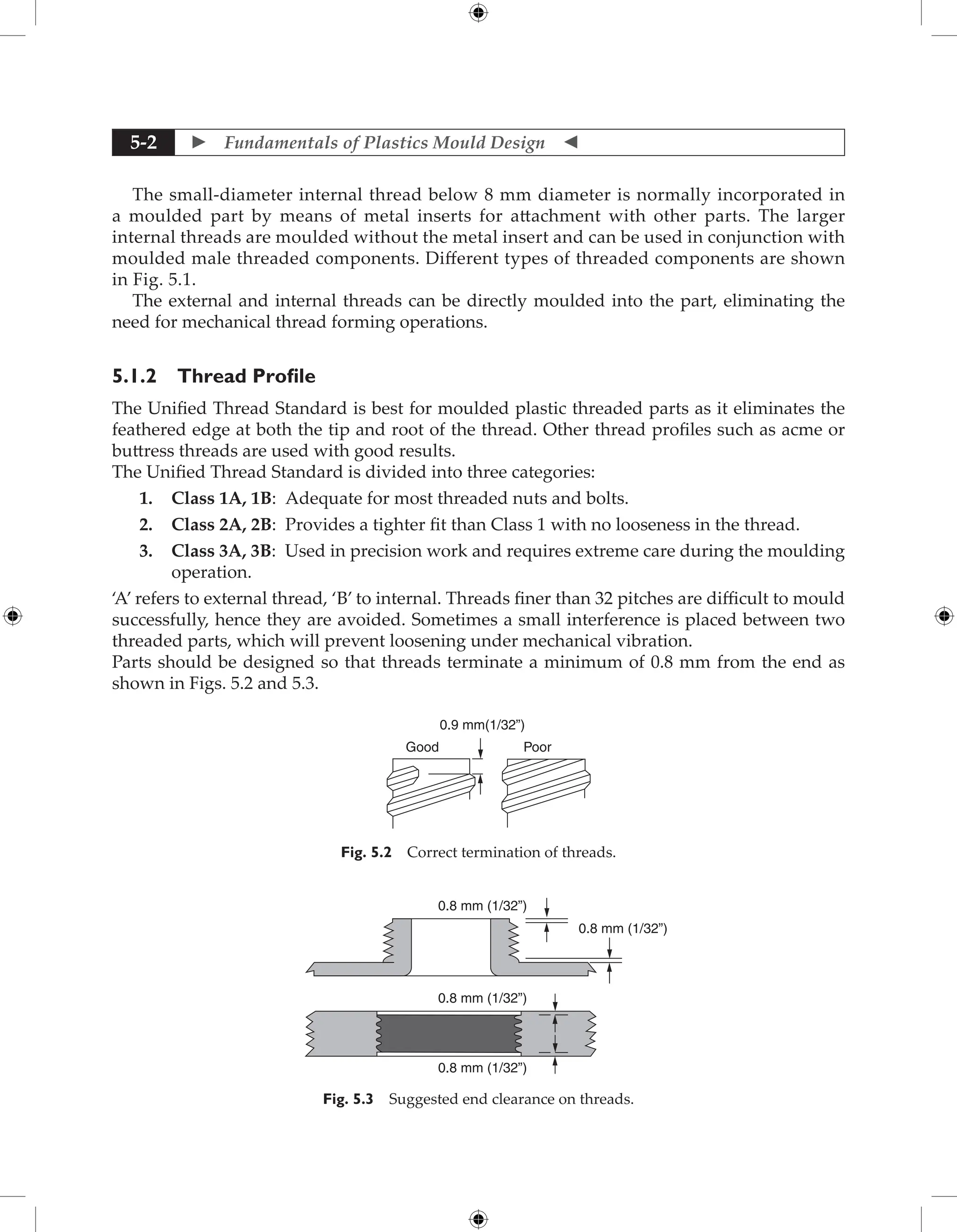

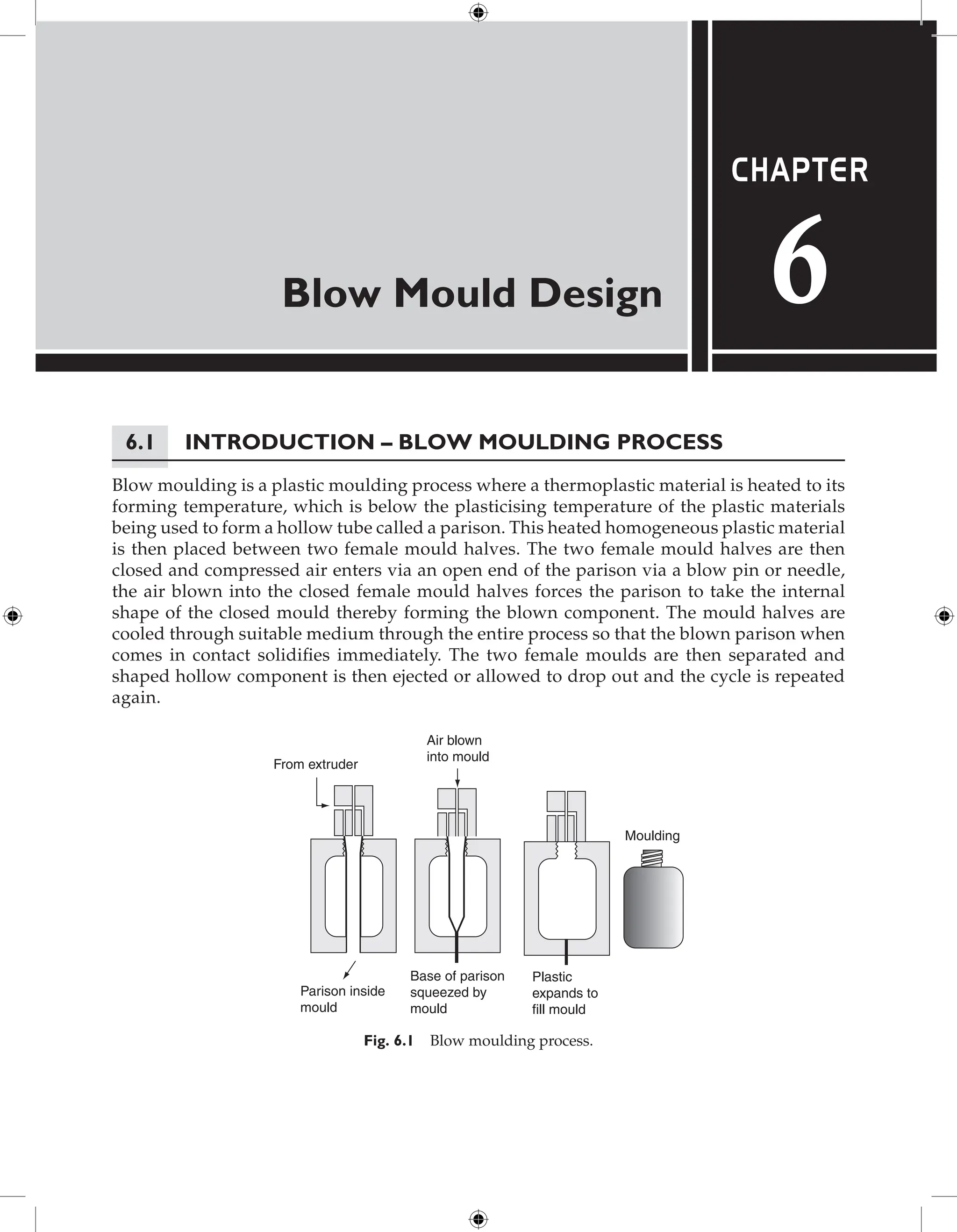

Helical channel design This design is adopted to en-

sure that the coolant follows a precise path and no

dead water is possible which results in rapid transfer

of heat from the moulding. Here the water follows

a helical path machined into a steel or brass block

which is fitted inside the chamber as shown in Fig.

2.158 and Fig. 2.159.

If the diameter or width is very small (less than

3 mm), only air-cooling is feasible. Air is blown at

the cores from the outside during opening or flows

through a central hole from inside as shown in Fig.

2.160. In this procedure the maintaining of exact

temperature is very difficult.

Better cooling of slender cores (those measuring less than 5 mm) is accomplished by using

inserts made of materials with high thermal conductivity, such as copper or beryllium-copper

materials. Such inserts are press-fitted into the core and extended with their base, which has

a cross section as large as is feasible, into a cooling channel as shown in Fig. 2.160.

2.7.5 Calculation of Rate of Heat to be Removed by Cooling Circuit

Q = M × [Cp {T 1 − T 2}+ L]

where Q = Heat to be transferred from mould per hour (cal/ hr)

Cp = Specific heat of material (cal/gm/ °C)

M = Mass of plastic material injected into the mould per hour (gm/hr)

L = Latent heat of fusion of plastic materials (cal/gm)

T1 = Injection temperature of material (°C ) ; T2 = Temperature of mould (°C)

2.7.6 Ejection Temperature

The operating temperature for a particular mould will depend on the following factors:

1. Type and grade of plastic material to be moulded

2. Length of flow within the impression

3. Wall section of the moulding

4. Length of the feed system

Maintaining the optimum temperature in a mould is very important as:

1. It improves the cycle time

2. It improves the quality of the product

3. It avoids distortion of the product

The holes or channels through which water/coolant passes are termed as flow ways and the

complete system of flow ways is called circuit.

Air

d

Fig. 2.160 Cooling of slender core insert.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fundamentalsofmoulddesign-231217032858-869d3d7e/75/Fundamentals-of-Mould-Design-lecture-pdf-296-2048.jpg)

![ Fundamentals of Plastics Mould Design

2-102

2.7.7 Weight of Water to be Circulated per Hour

The following formula gives weight of water to be circulated per hour to dissipate the heat;

Q = k m1 (Tout - Tin)

where Qw = Rate of heat extracted (kcal/hr)

k = Constant to allow for heat transfer efficiency

m1 = Weight of water passed (gm/hr)

Tout – T in = 5°C

For the component shown in the Fig. 2.2, the value of Q can be calculated as follows:

Q = 2316 × [0.5 × (250–60) + 20.1]

=

266571.6 cal/hr. = 266.57 kcal/hr (Assuming single impression and 1 min. cycle

time)

where Cp =

0.5 cal/° C/gm for PP; M = Shot wt. of the product × No. of shot/hr. = 38.6 gms.

(including 10% feed system) ; L = 20.1 cal/gm. For PP; T1 = Injection temp. of

PP; T2 = Mould temp. for PP

Weight of water to be circulated per hour is 266571.6 = 0.64 × m1 × 5 ; m1 = 83303.625 gm/hr =

83.3 kg/hr.

2.7.8 Cooling Time

Theoretically, cooling time is proportional to the square of the heaviest part wall thickness or

the power of 1.6 for the largest runner diameter. That is given in Table 2.15.

Table 2.15

Cooling time=

(Heaviest wallthickness)

Thermaldiffusivityof po

2

l

lymermelt

Cooling time=

(Largestrunnerdiameter)

Thermaldif

1.6

f

fusivityof polymermelt

wherethethermaldiffusivityof polymerme

eltisdefinedas

Thermaldiffusivity =

(Thermalconductivity)1.6

(

(Density)(Specificheat)

In other words, doubling the wall thickness quadruples the cooling time

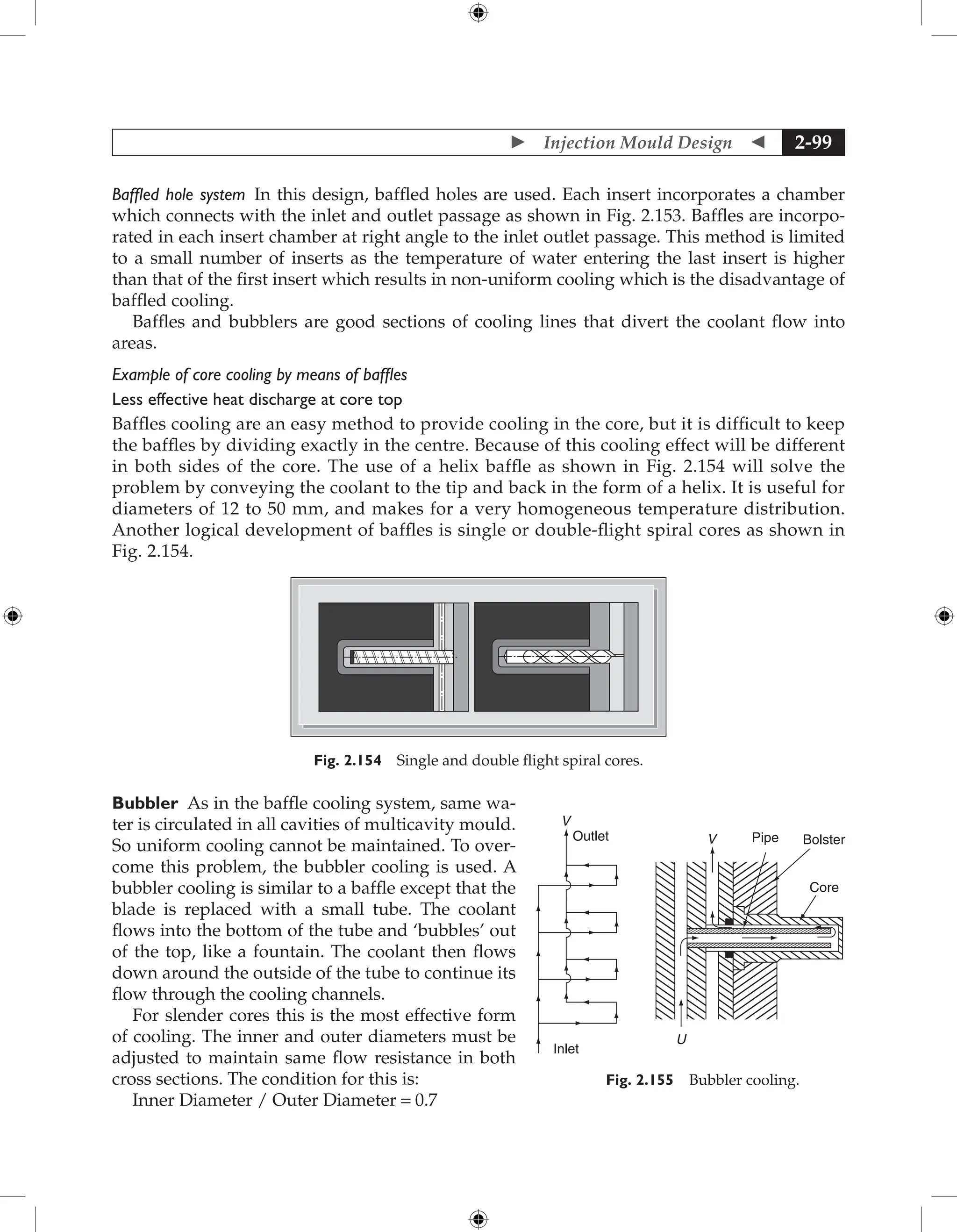

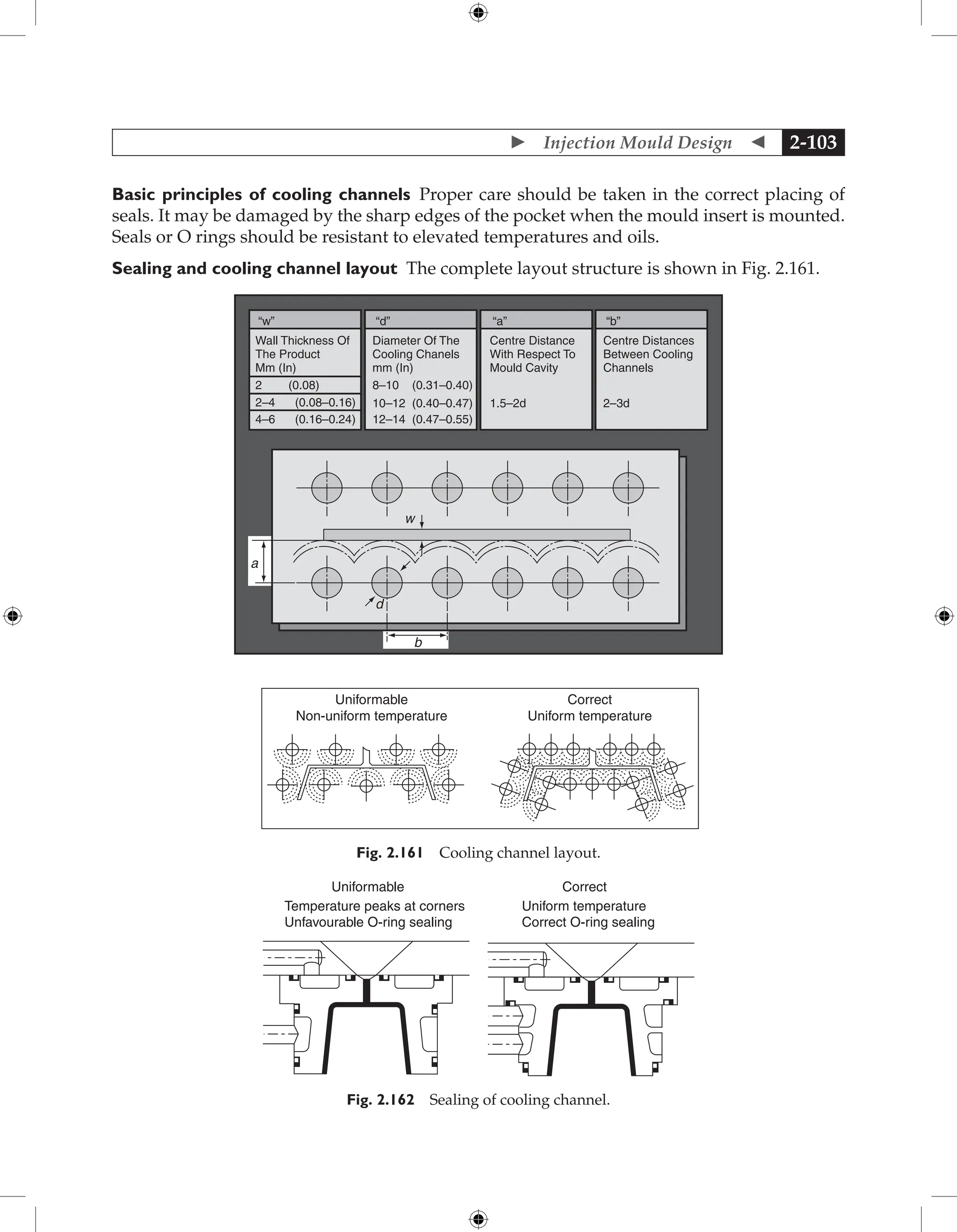

2.7.9 Cooling Channel Configuration

In general, the cooling system will be roughly drilled or milled. Rough inner surfaces enhance

turbulent flow of coolant, thus, providing better heat exchange. Turbulent flow achieves 3 to

5 times as much heat transfer as does non-turbulent flow. Cooling channels should be placed

close to the mould cavity surface with equal centre distances in between. The mechanical

strength of the mould steel should be considered when designing the cooling system.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fundamentalsofmoulddesign-231217032858-869d3d7e/75/Fundamentals-of-Mould-Design-lecture-pdf-297-2048.jpg)

![ Fundamentals of Plastics Mould Design

2-120

Pressure drop

1

(Area at external pathway)

1

(Area at internal pat

2

a -

h

hway)2

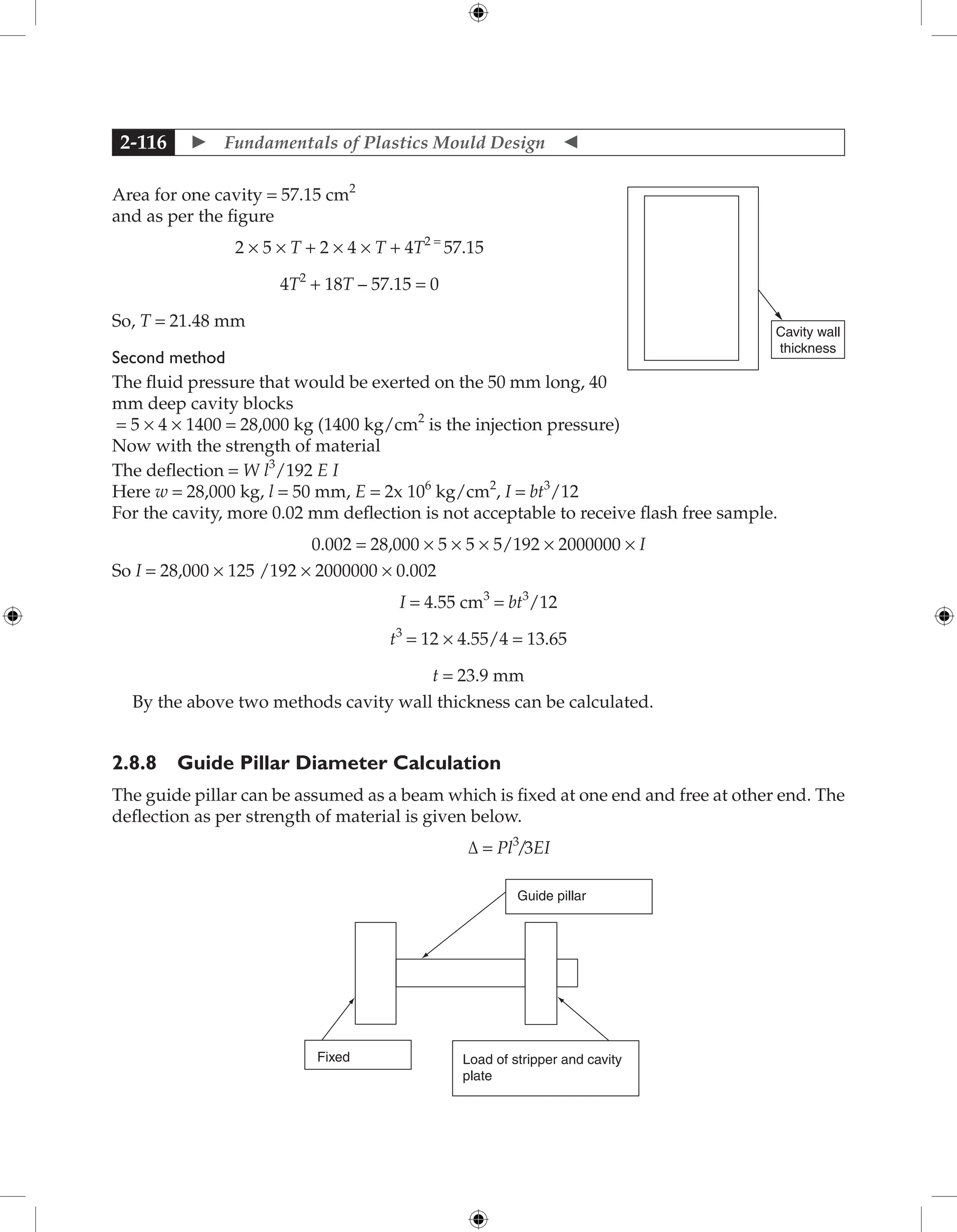

2.8.14 Design of Step Ejector Pin

The critical force that will cause buckling of the ejector pin can be calculated as follows:

P = 2p 2

EM/l2

where P = Critical load (Kg), E = Modulus of elasticity (Kg/cm2)

M = Moment of inertia (cm4

), and l = Critical length (cm)

And stripping force which is required for the stripping of the moulding from the core

d1

d2

I

I1

I−I1

For the ejection;

Stripping force = P = 2 p 2

EM/l2

= 2p 2

E p d4

/64l2

= p3

Ed4

/32l2

Stripping force = P = (St × E × A × f p) / [d × (d/2t−d × Pp/4t)]

St = Coefficient of thermal expansion × temperature difference between softening point and

ejection temperature × d (cm)

E = Elastic modulus (kgf/cm2

)

A = Total area of contact between moulding and mould faces in line of draw (cm2

)

f p = Coefficient of friction between plastics and steel

d = Diameter of circle of circumference equal to length of perimeter of moulding

surrounding male core (cm)

t = Thickness of moulding

Pp = Poisson`s ratio of plastics

In the step pin, the diameter (d1)of the portion which is in contact with the plastic material is a

known quantity as per the wall thickness of moulding. We have to calculate the length (l1) of

this portion that can be done by placing d1 and find the length l1from the above equation.

After finding l1 from the above equation, the diameter of other portion d2 of the step pin can

be calculated by placing length of this portion l2 (total length – l1) in the above equation.

2.8.15 Heaters

The calculation is done to calculate number of heaters required for manifolds

Manifolds dimension is a × b × c](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fundamentalsofmoulddesign-231217032858-869d3d7e/75/Fundamentals-of-Mould-Design-lecture-pdf-315-2048.jpg)

![ Fundamentals of Plastics Mould Design

2-122

S = Total manufacturing cost of the parts

By the above we may conclude that

No. of cycle required = n/x

Total time required = n T/x seconds = nT/60 x minutes

Total worker cost with overhead = n T w(1+r)/x

So S = {nT The temperature difference between mould plates and other plates from platen

side or platen w(1 + r)/60x} + Ax + B

This is the equation for the total cost of the parts. By differential calculation we try to get the

very economical number of cavities by assuming minimum manufacturing cost. For getting

this differentiates the equation with respect to x.

d/dx(S) = d/dx[{nTw(1+r)/60x} + Ax+B]

= d/dx[{nTw(1+r)/60x} + d/dx (Ax) + d/dx (B)]

= d/dx{nTw(1+r)/60x} + A

= d/dx{nTw(1+r)x-1

/60} + A

= -nTw(1+r)x–2

/60+ A = 0

A = nTw(1 + r)x–2

/60

x2

= nTw(1 + r)/60A

x = √nTw(1 + r)/60A by putting the values

x = √{1,00,000 × 60 × 25(1+0.15)/60 × 10,000}

x = 16.9 = 16 number of cavities

For the above data, 16 is the economical number of cavity. Now we have compared the

number with the technological number of cavity. Whichever is less, we have to design the

mould for that number.

2.8.17 Cost Reduction through Design Arrangement

1. Cost of the mould: The cost of a particular mould is expensive. To reduce the cost of the

mould, it would be better to go for multicavities injection mould by which the cost of one

product can be reduced. Take one example.

2. By the production of large quantities: The approximate cost of a mould that may make a

lunch box moulding may be Rs. 50,000 to Rs. 1,00,000. The capital cost is of course expensive

but consider that a single mould may produce ten lakhs of mouldings. Therefore, the unit cost

of each moulding can be very low because they are manufactured in such large quantities.

3. By the fabrication of multi-impression mould: DME can be further reduced by fabricat-

ing the mould in multicavities. In multicavities mould the cost of mould is increased by 1.4 to

1.5 times but the production cost is reduced due to number of cavities per cycle time.

4. By the fabrication of family type of mould: The mould cost is also reduced by fabricating

family type of mould.

5. By quick change insert system: By fabrication of one mould with different type of its

insert, cost of the mould can be reduced by quick- change tooling systems. These kits offer](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fundamentalsofmoulddesign-231217032858-869d3d7e/75/Fundamentals-of-Mould-Design-lecture-pdf-317-2048.jpg)

![ Compression Mould Design 3-15

3.9.2 Economical Determination

Let us assume that

1, 00,000 pcs = n = The total number of parts are required by the party.

x = Number of mould cavities to be fabricated

r = 15% of wages/hr = Overhead cost

w = ` 25 per hour = Wages of the workers

A = Production and maintenance cost of one cavity = ` 10,000/-

B = Production cost of mould casing

T = Cycle time = 60 seconds

S = Total manufacturing cost of the parts

By the above we may conclude that

No. of cycle required = n/x

Total time required= n T/x seconds = nT/60x minutes

Total worker cost with overhead = n T w(1 + r)/x

So,

S = {nT The temperature difference between mould plates and other plates from platen side

or platen

w(1 + r)/60x} + Ax + B

This equation derives the total cost of the part. By differential calculation, we try to get the

very economical number of cavities by assuming minimum manufacturing cost. For getting

this, differentiate the equation with respect to x.

d/dx(S) = d/dx[{nTw(1 + r)/60x} + Ax + B]

= d/dx[{nTw(1 + r)/60x} + d/dx (Ax) + d/dx (B)]

= d/dx{nTw(1 + r)/60x} + A

= d/dx{nTw(1 + r)x-1

/60} + A

= -nTw(1 + r)x-2

/60 + A = 0

A = nTw(1 + r)x-2

/60

x2

= nTw(1 + r)/60A

x = √nTw(1 + r)/60A by putting the values

x = √{1,00,000 × 60 × 25(1 + 0.15)/60 × 10,000}

x = 16.9 =16 number of cavities

For the above data, 16 is the economical number of cavity. Now we have compared the number

with the technological number of cavity. Whichever is less, we have to design the mould for

that number.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fundamentalsofmoulddesign-231217032858-869d3d7e/75/Fundamentals-of-Mould-Design-lecture-pdf-348-2048.jpg)

![ Fundamentals of Plastics Mould Design

7-18

die dimensions and these dies are designed especially

for extrusion of specific plastics and their compounds.

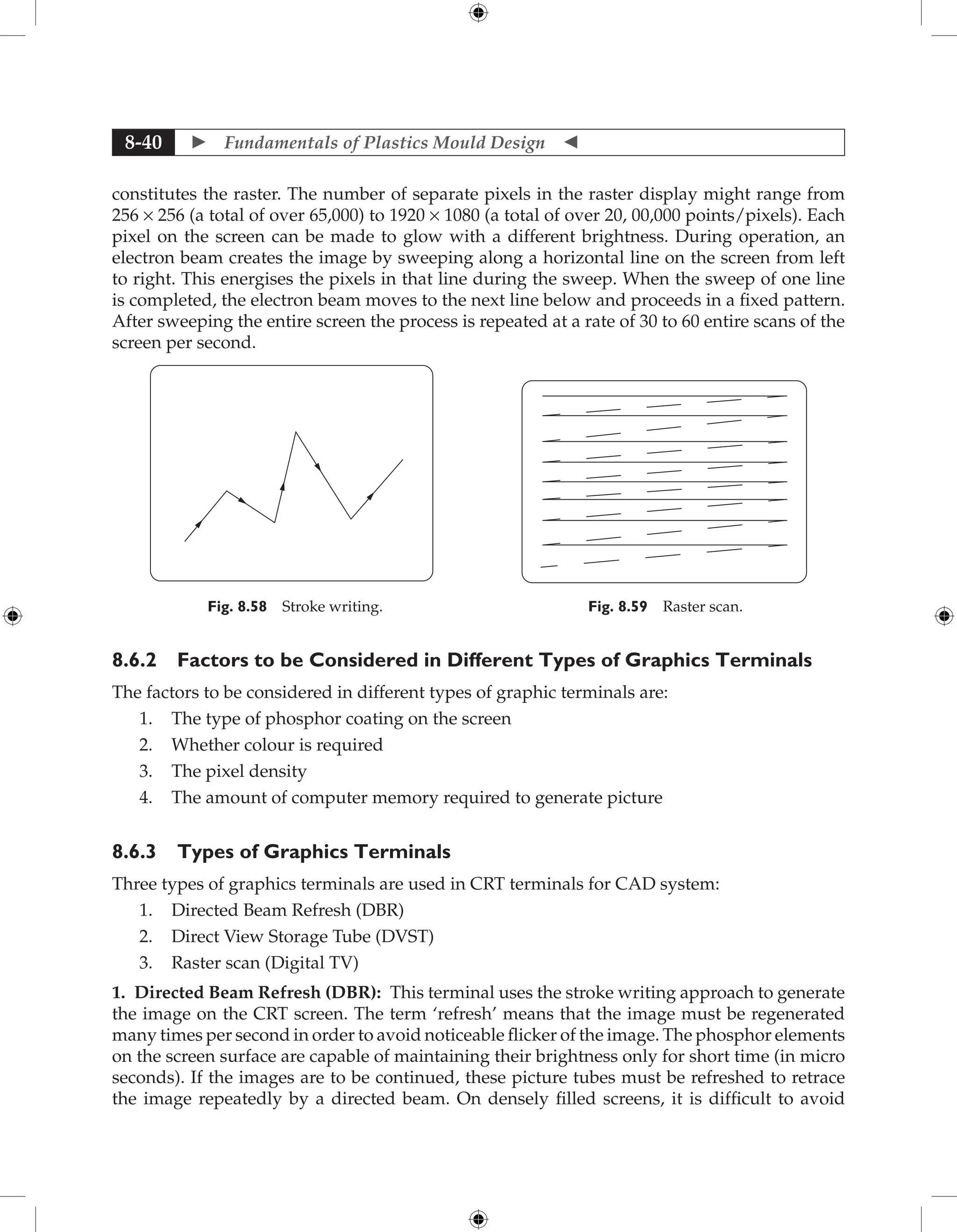

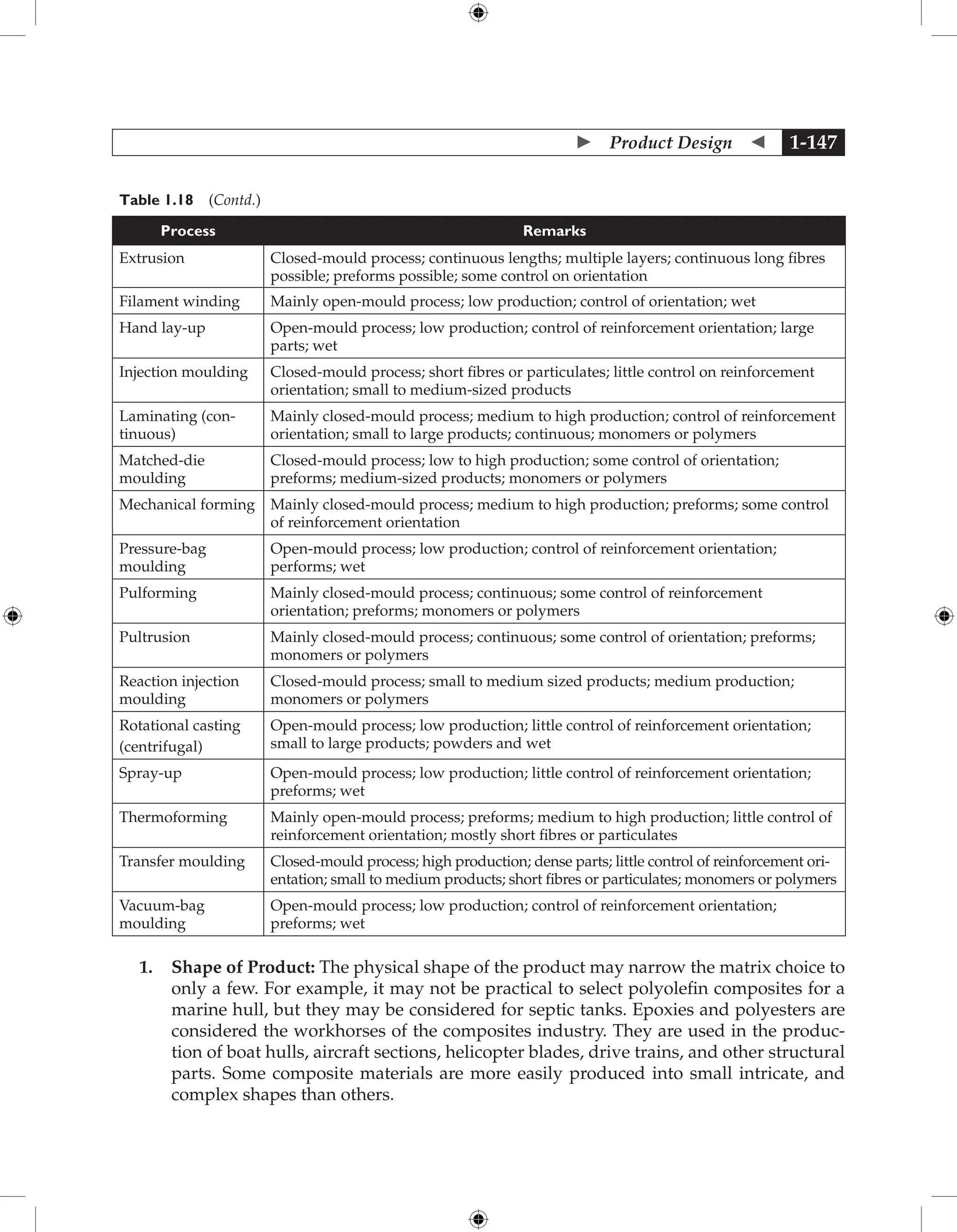

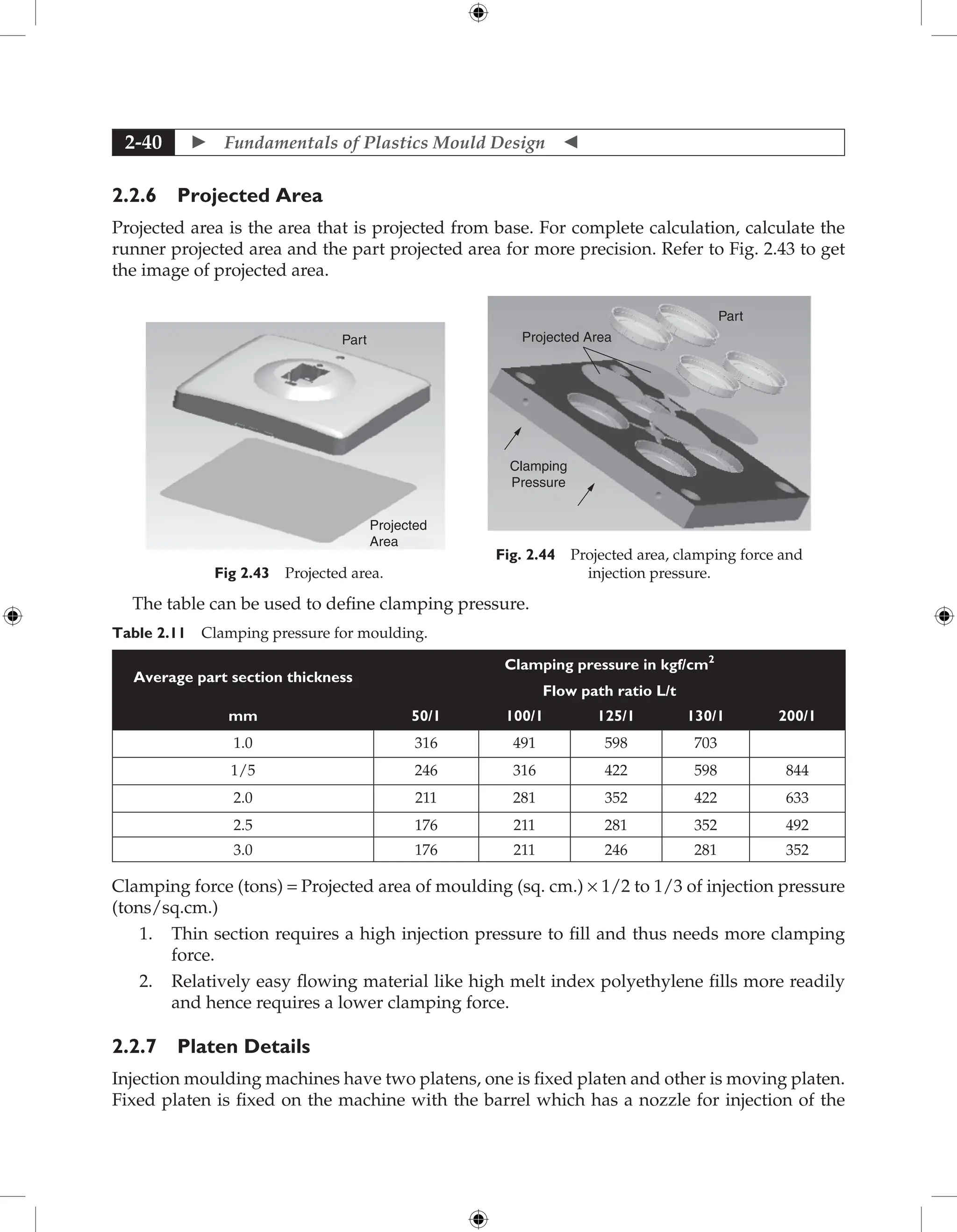

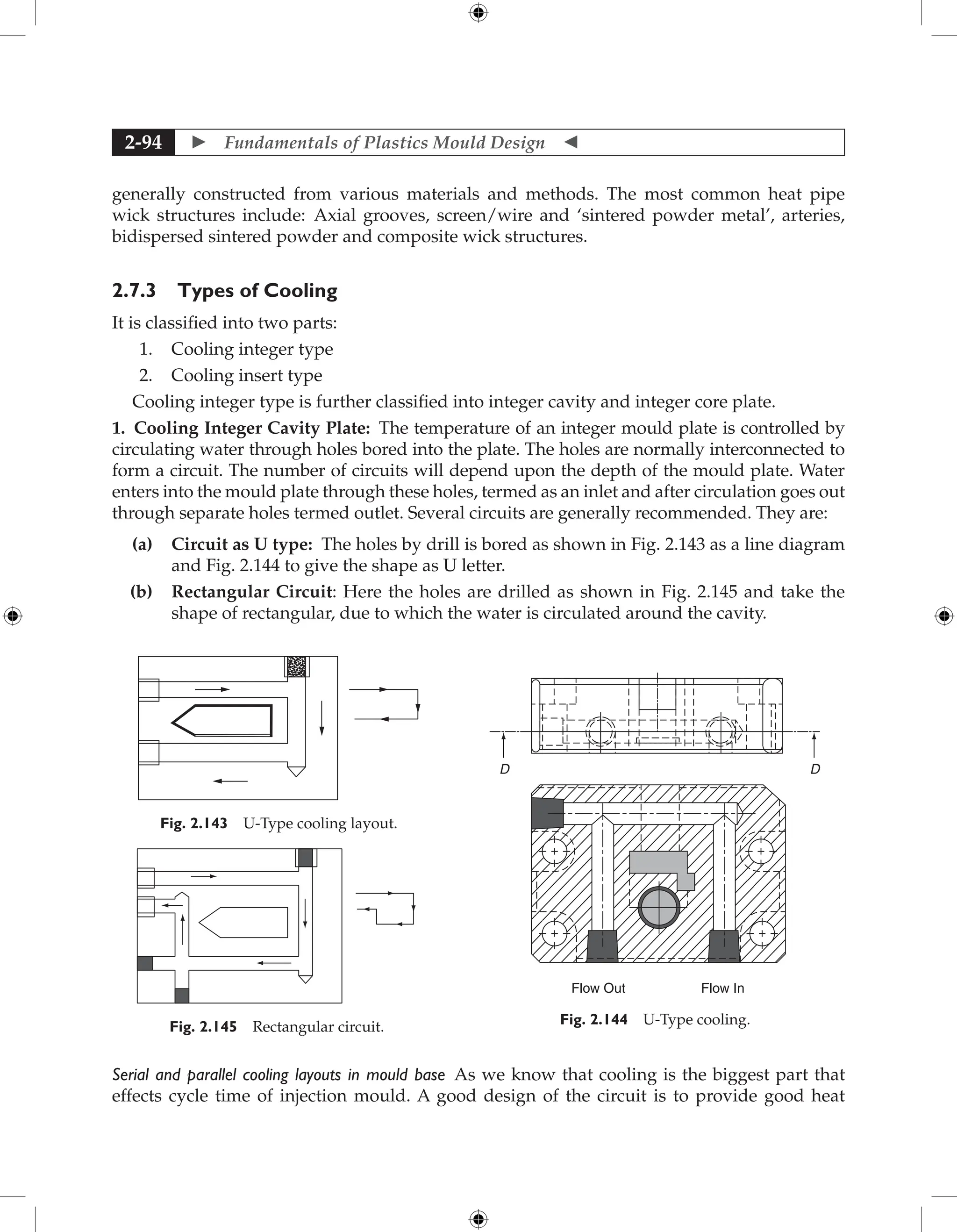

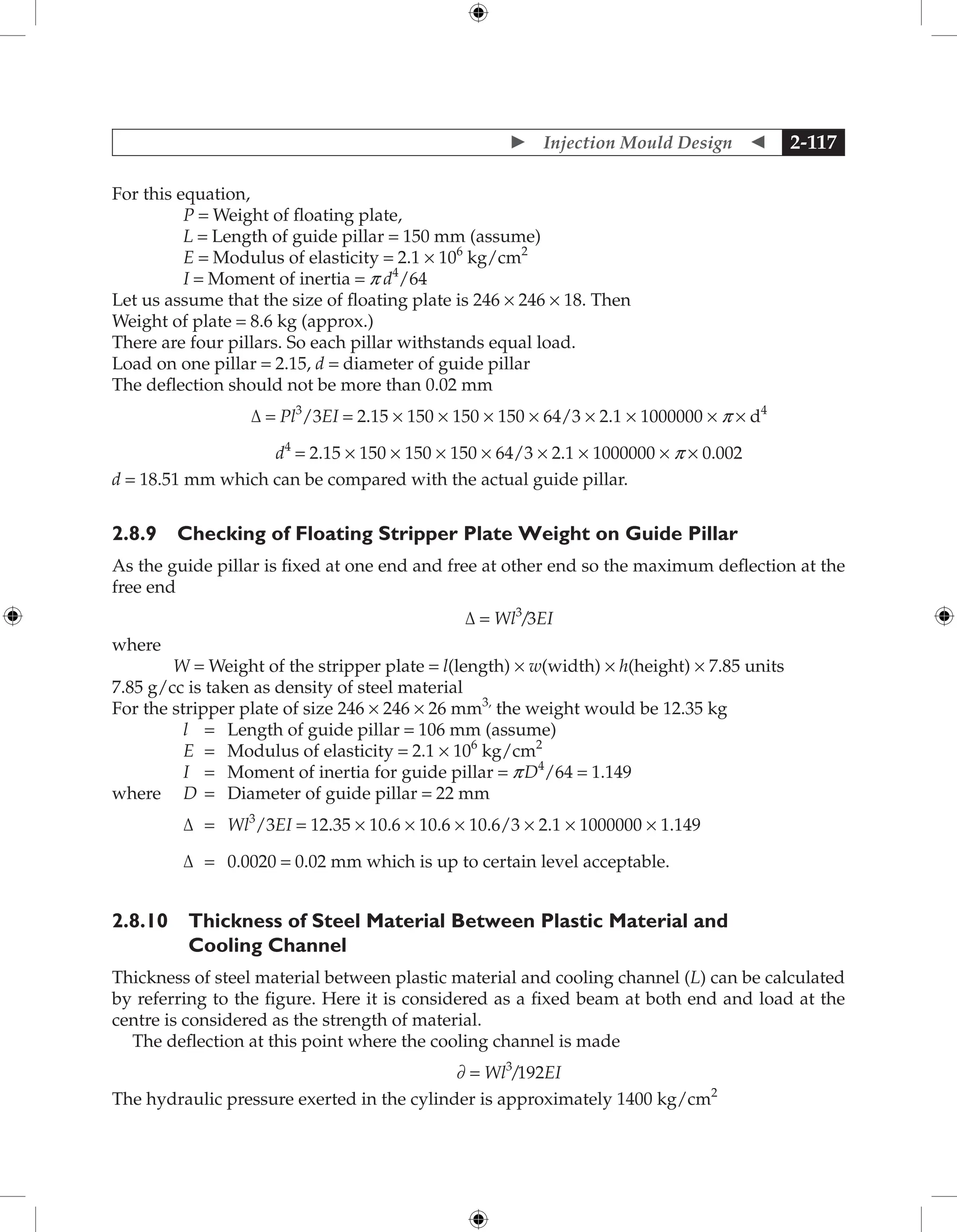

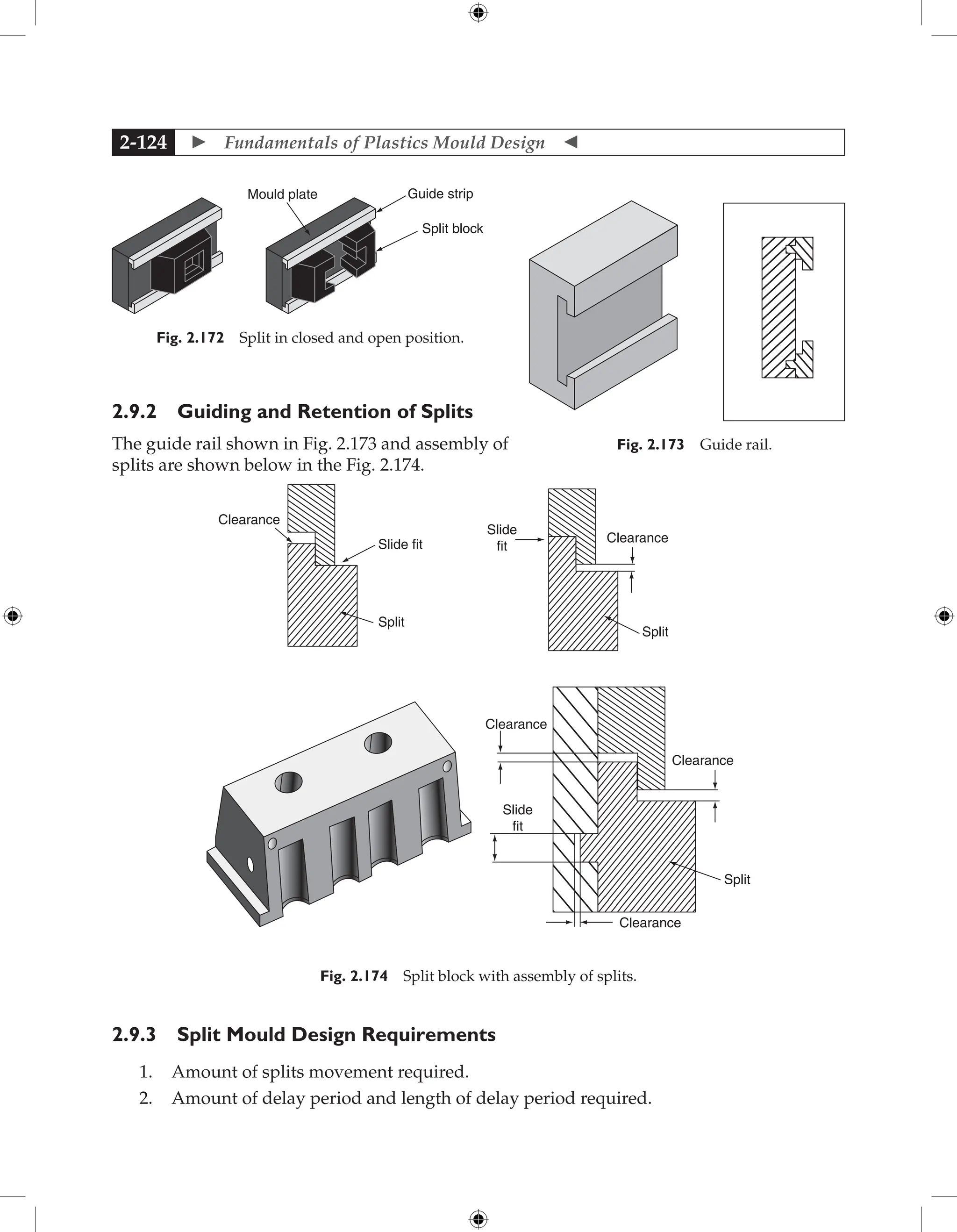

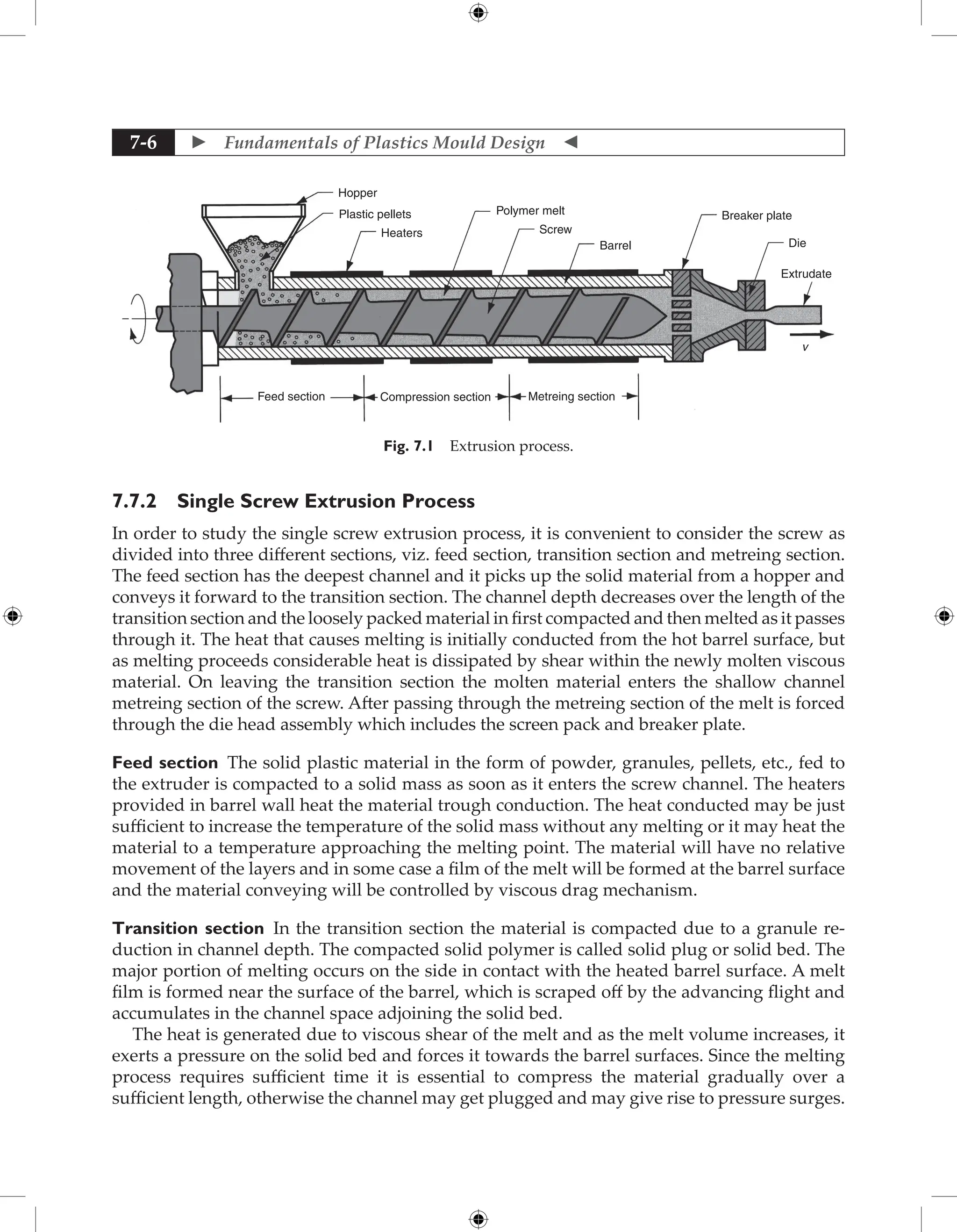

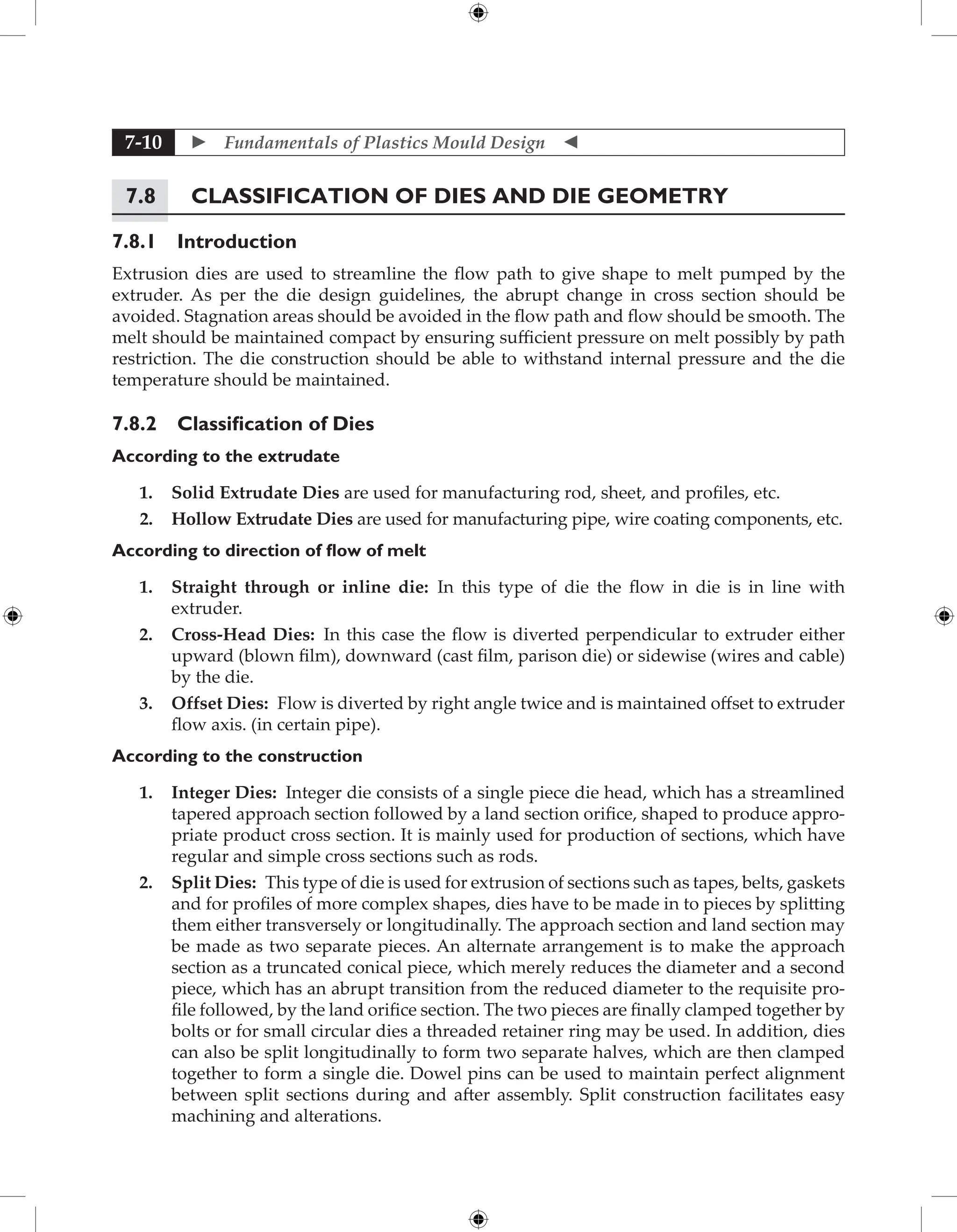

7.9.2 Rod Die

The rod die has a simpler geometry and it consists of

an approach section with a taper of 60° to 90° included

angle. The length of the land depends on the material

extruded, rod diameter, extrusion rate, etc., and special

care to be taken while designing dies for crystalline

polymers such as nylon and polyacetal. In these

materials, rapid volume change takes place during post

extrusion cooling and solidifying, which will create

voids in the central portion of rods. With amorphous

polymers such as polycarbonate and PVC, the change

in specific volume is more gradual and limited.

The method of extruding rods in nylon is free extrusion into a water quench bath which

requires a circular die land that has a diameter 1.7 to 2.0 times the diameter of the desired rod.

A closely balanced cooling system is necessary to obtain a round, void-free rod. Shrinkage

voids are usually eliminated by shortening the length of quench bath, by air quenching

or by a hot oil bath. This method is suitable for making rods up to 12.5 mm diameter. For

larger diameter rods or where precise control of diameter is desired, a forming box method is

used. The molten mass is extruded under pressure through a short die land, then through a

converging section and finally through a cylindrical water-cooled tube. The rod is thus shaped

by the pressure from the extruder, which supplies the melt continuously to the central cone

and eliminates voids due to shrinkage.

Example for design of die for a rod

Data given or assumed

Extruder size [Es] - 45 mm

Extruder output (Qm) - 30 kg/hr

Rod diameter[Pd] - 15 mm

Material- L. D. polyethylene

Properties

Solid density (rs) - 0.923 gm/cm3

Melt density (rm) - 0.76 gm/cm3

at 170°C

Power law constants (at 170°C)

(n) - 1/3

(k) - 3250 kg (f) sec-1

/ m2

Extensional viscosity (l) - 0.822 * 104

kg (f) sec/ m2

Critical extensional strain rate (ee) - 18 sec-1

La L

t

E

s

D

b

Fig. 7.10 Rod die.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fundamentalsofmoulddesign-231217032858-869d3d7e/75/Fundamentals-of-Mould-Design-lecture-pdf-522-2048.jpg)

![ Extrusion Dies 7-19

Permissible tensile strength of die material (f) - 1400 kg/cm2

Design Calculation

1. Volumetric output of extruder

Qv = Qm × 1000 / rm

= (30*1000)/ 0.76 = 39500 cm3

/hr

2. Velocity of melt

V = Qv/A = (Qv/60) * (4 / p Es2

)

= (39500/60) * (4/p 0.452

) = 372 cm/min = 3.72 m/min.

Land section

Assuming land length to be twice the product wall and land wall to be 10% larger than product

to accommodate draw down.

Land section (L) = 30 mm

Land diameter (D) = 16.5 mm

Designing for length of approach section

PL = [((3n + 1)/n) (Qv / pR3

)] n (2kL / R)

where Qv = Volumetric flow rate

R = Radius of land

L = Length of land

PL = Pressure drop in land

K and n are power law constants

PL =

[(((3 × 1/3) + 1)/ (1/3)) × (39500/ (60 × 60)) × (1 / (p × (1.65/2)3

))] 1/3

× [((2 × 3250)/

104

) × (3 /(1.65/2))]

= 6.25 kg / cm2

Shear stress

tw = (RP)/2L = (1.65 × 6.25) / (2 × 2 × 3.0)

= 0.859 kg / cm2

Shear rate

gw = ((3n + 1) / n) ( Qv / pR3

)

= 6 × (39500/(60 × 60)) ( 1/( p (1.65/2)3

)

= 37.74 sec-1

Approach section

To calculate approach angle a

tan a = 2 ec / g

where ec = Critical extensional strain rate

g = Shear rate

tan a = 2 × 18/37.74 = 0.954

a = 43o

40’](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fundamentalsofmoulddesign-231217032858-869d3d7e/75/Fundamentals-of-Mould-Design-lecture-pdf-523-2048.jpg)

![ Fundamentals of Plastics Mould Design

7-20

Extruder size = 45 mm

Tan a (45 – 16.5) / ( 2 * La )

where La = Length of approach section

La = 15.1 mm.

Calculation for Minimum Thickness of Die Wall

Pressure drop in the approach section

Ps = (2t/3n tan a ) [ 1 – (R0/Ri )3n

]

= (2 × 0.859)/(3 × 1/3 × 0.954) [ 1 – (16.5/45)3 × 1/3

]

= 1.14 kg/cm2

Pe = ((2lec)/3) [ 1 – (R0/Ri )3

]

= ((2 × 0.822 × 104 ×

18 )/3) [ 1 – (16.5/45)3

]

= 9.38 kg/cm2

So, pressure drop in approach section = 1.14 + 9.38 = 10.52 kg / cm2

Assuming no pressure drop in the breaker plate, screen pack and the adapter.

Total pressure drop in die (Pt) = Pressure drop in land + Pressure drop in approach

Pt = 6.25 + 10.52 = 16.77 kg / cm2

Minimum die wall thickness (t)

From Eq. t = (D/2) [ ( ( f + Pt ) / ( f – Pt ))1/2

− 1 ]

where, D = Land diameter

f = Permissible tensile strength of die material

Pt = Total pressure drop in die

So, t = (16.5/2) [((1400 + 16.77) / (1400−16.78))1/2

− 1 ]

= 8.25 * 0.01 = 0.0825 mm.

Actual wall thickness is to be decided depending upon assembly situation.

7.9.3 Pipe Die

Pipe is basically a hollow and symmetric round cross sections and a pipe extrusion line is

very similar to a profile line with a vacuum sizing cooling unit, puller, and saw or on cutter.

Products can be rigid or flexible and vary from something very small, such as a catheter tube

used in medical applications, to large-diameter pipe used to transport water or other fluid.

Pipe or tubing can be wound up as a continuous product or cut to length. Pipe and tubing can

be extruded for added value and to meet specific end-use requirements.

There are different types of die used for manufacturing of pipes. Various types of dies are

in line or straight through or offset type.

Function of die

The extrusion head or die is determined by the diameter and wall thickness required in the

final product. The extrudate enters directly from the extruder through the breaker plate into

the die. Large dies require a die stand to support the die weight and prevent distorting the

extruder barrel. An adapter is present between the extruder and the pipe or tubing die, versus

the direct connection the entrance cone distributes the melt uniformly around the mandrel.

The mandrel or centre section is held in place by spokes radiating out from the mandrel called](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fundamentalsofmoulddesign-231217032858-869d3d7e/75/Fundamentals-of-Mould-Design-lecture-pdf-524-2048.jpg)

![ Extrusion Dies 7-23

the dimensions of the flow channel in the spider. This helps to reduce the obstruction to melt

flow in the spider channels. High melt temperature and frictional drag in the spider passage

should be avoided. The ratio between the land length and the annular gap which forms the

wall thickness varies between 10 to 30. The annulus is usually designed to oversize to allow

for some draw down and an excess diameter of 10 to 30 per cent is usual. The mean diameter

of the annular gap should be 5 to 25 per cent larger in the case of pipes. The lower values refer

to rigid PVC and larger values to polyolefin’s.

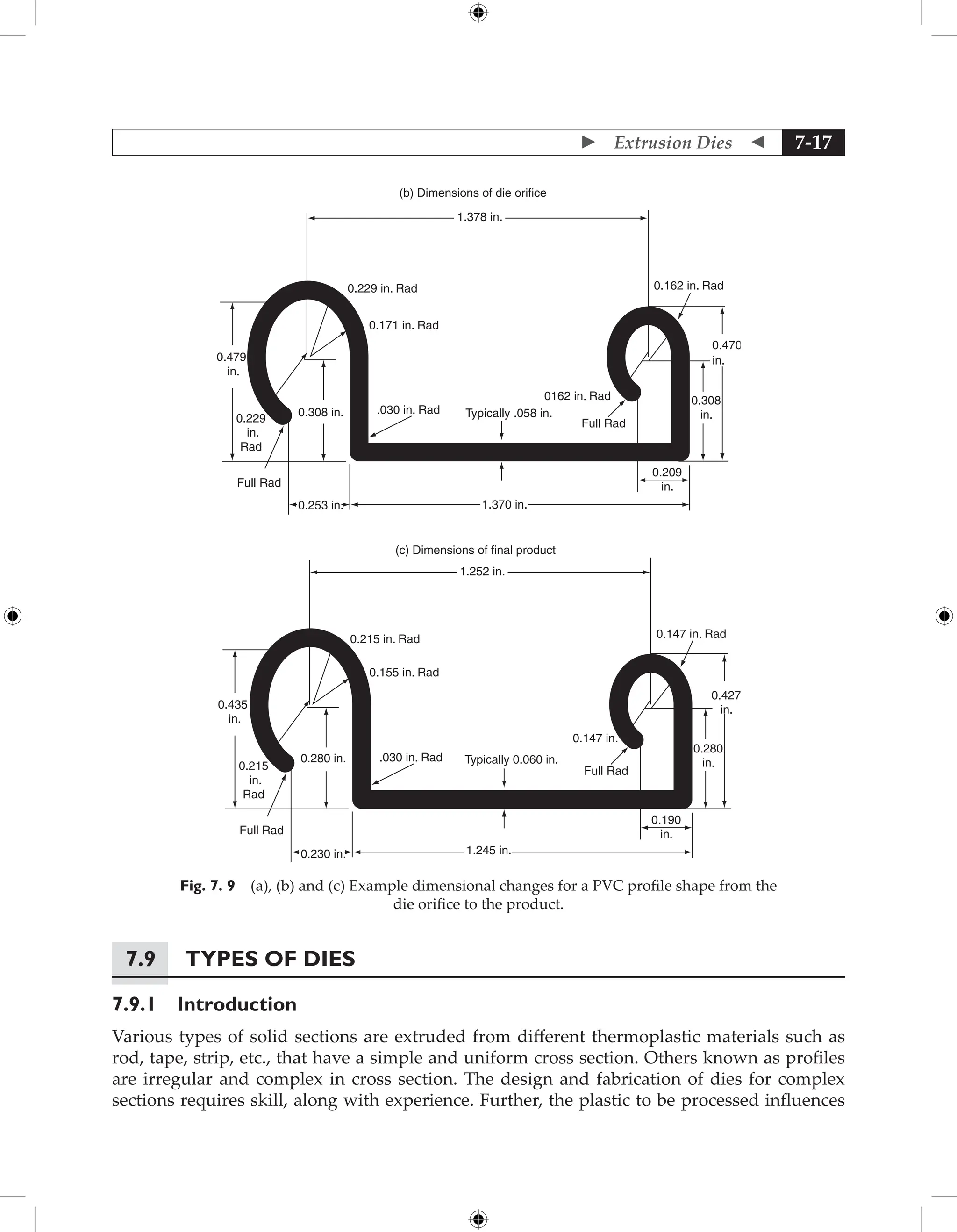

Cross section of flow should gradually decrease from section ‘z’ to ‘y’ to ‘w’ (see Fig. 7.11).

Example for design of in-line pipe die

Data given or assumed -

Extruder size [Es] - 65 mm

Extruder output (Qm) - 60 kg/hr

Outside diameter of pipe - 90 mm

Thickness of pipe - 4.5 mm

Material and its property - H.D. Polyethylene

Density of solid (rs) - 0.955 g /cm3

Density of melt (rm) - 0.81 g /cm3

at 170°C

Power-law constants

K - 631 kg(f) sec- 0.56

/m2

n - 0.56

Design calculation

1. Volumetric output of extruder

Qv = Qm × 1000 / rm

= (60 × 1000) / 0.81 = 74074 cm3

/hr

2. Velocity of melt V = Qv/A = ( Qv/60 ) × (4/p Es2

)

= (74074/60) × (4/p 0.652

)

= 372 cm/min = 3.72 m/min.

Land section

Assuming land length to be 15 times the product wall thickness and land wall to be 2% larger

than product to accommodate draw down.

Outside diameter of annulus - 90 * 1.02 = 91.8 mm

Inside diameter of annulus (mandrel diameter) - 91.8 - (4.5 * 2) = 82.8 mm

Land length - 15 * 4.5 = 67.5 mm

Shear rate in land

Shear rate (g ) = (6 Qv) / [ p (R0 + Ri)(R0 - Ri)2

]

= (6 * 74074) / [ p (4.59 + 4.14)( 4.59 – 4.14)2

× 3600 ]

= 22.24 sec-1](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fundamentalsofmoulddesign-231217032858-869d3d7e/75/Fundamentals-of-Mould-Design-lecture-pdf-527-2048.jpg)

![ Fundamentals of Plastics Mould Design

7-24

where Qv = Volumetric output of extruder

Ri = Inlet radius of taper

R0 = Outlet radius of taper

Pressure drop in land can be obtained from (assuming thickness very less compared to

radius)

Qv = (n / (2n + 1)) * (p R0

3

) [ (R0 P) / (2KL) ] 1/n

( (b - 1) / b )((2n + 1) / n)

( ( 1 + b ) / 2b )

where P = Pressure Drop in Land

b = R0 / RI = 4.59 / 4.14 = 1.11

k, n = Flow behaviour index

Ri = Inlet radius

R0 = Outlet radius

L = Land length

Q =

{(0.56/2.12) × p × (4.59)3

) [ (4.59DP)/(2(631/104

))]1/0.56

((0.11–1.11)(2.12/0.56)

(2.11/2.22)}

= 0.012 × (5.388 P)1.785

P1.785

= 22.24 / ( 0.012 × 20.21) = 91.71

P = 12.57 kg / cm2

Approach section

Assuming angle of approach (convergence) b = 20°

2b = 40°

and assuming 2 a = 10°

Assuming the length of approach section = 100 mm

Pressure drop in approach section = Due to simple shear flow (Ps) + Due to Extensional

Flow (Pe)

Ps = ( Kg n

/ Ho ) (1 / (U - V)) loge [ (1 + UL) / (1 + VL) ]

Pe = [ 1 − (RoHo

2

/ RiHi

2

) ] l / 2

where K, n = Power law constant; g = Shear rate;

l = Viscosity under simple tension

Ro = Mean radius in outlet of approach section

Ri = Mean radius in inlet of approach section

Hi = Half Gap in inlet of approach section

Ho = Half Gap in outlet of approach section

L = Length of approach section

U = ( (tan a sec b ) / Ho )

V = n [ (tanb / Ro ) + 2U ]

U = ( (tan a sec b ) / h0 ) = (0.0875 × 1 ) / (( 0.45/2) × 0.94 ) = 0.41 cm

V = n [ (tanb / R0 ) + 2U]

= 0.56 [ (0.364 / 4.59 ) + (2 × 0.41) ]

= 0.56 × 0.899

= 0.5 cm](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fundamentalsofmoulddesign-231217032858-869d3d7e/75/Fundamentals-of-Mould-Design-lecture-pdf-528-2048.jpg)

![ Extrusion Dies 7-25

Ps =

(631/104

) × ((22.24)0.56

/0.45) × (1/(0.41 – 0.5)) loge [ (1 + (0.41 × 10)) / (1 + (0.5 × 10))

]

= (631 / 104

) × ((22.24)0.56

/0.45) × (- (1/0.09)) × (–0.1625) = 1.438 kg/cm2

Pe = Assumed negligible

The total pressure drop

Pt = Papproach + Pland = 1.438 + 12.57 = 14.008 kg/cm2

.

Minimum die wall thickness ( t )

t = (D/2) [ ( ( f + Pt ) / ( f – Pt ))1/2

− 1 ]

where D = Land diameter; f = Permissible tensile strength of die material

Pt = Total pressure drop in die

t = (91.8/2) [ ( (1400 + 14) / (1400-14))1/2

- 1 ] = 0.23 mm.

Actual wall thickness is to be decided depending upon assembly situation.

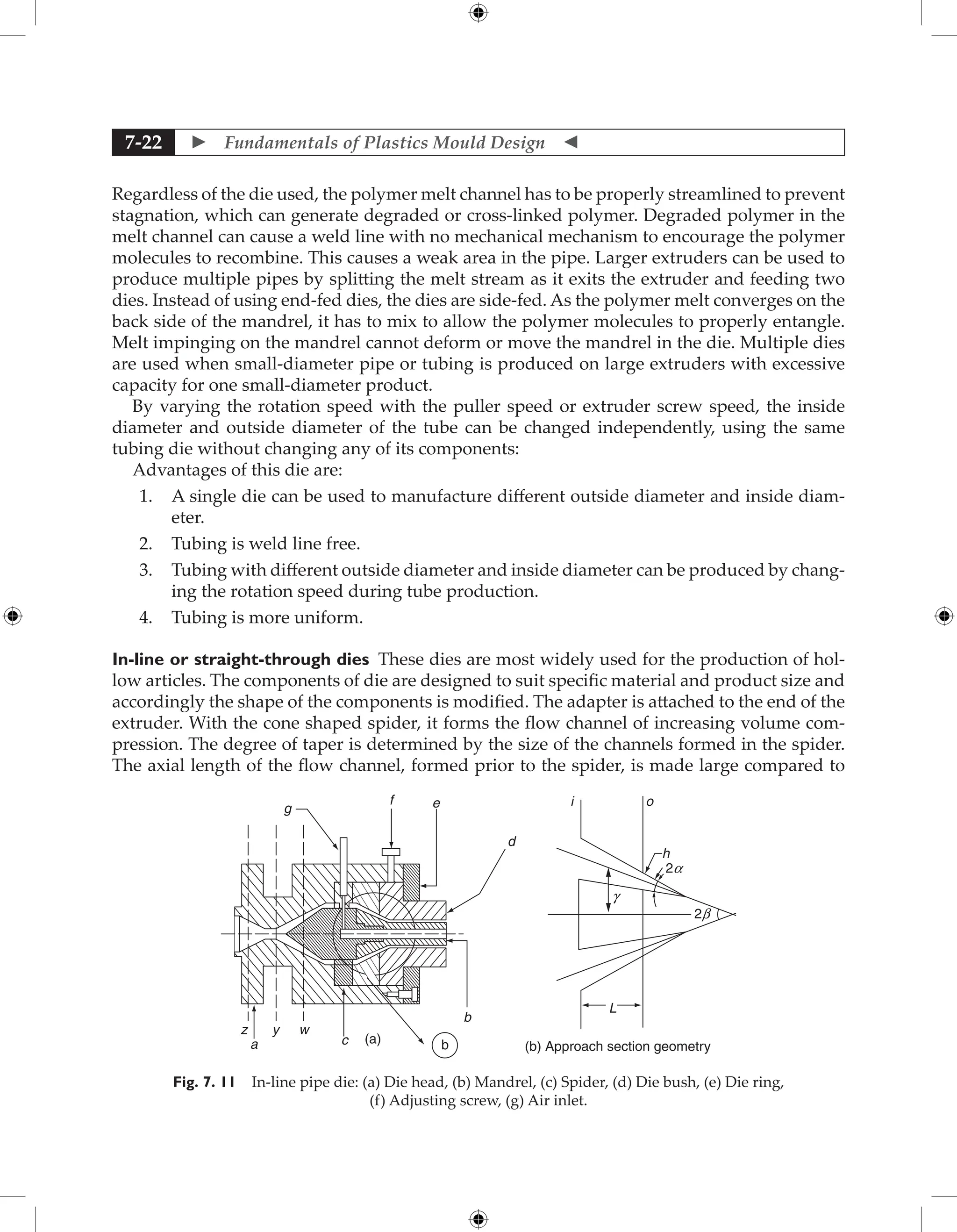

7.9.4 Offset Dies

Offset dies are used in certain special cases like production of pipes. The flow is diverted twice

by right angle to offset flow parallel to axis of extruder.

(a)

(b)

(d)

(c)

(e)

Fig. 7.12 Offset pipe die: (a) Die head, (b) Adapter, (c) Mandrel, (d) Die bush,

(e) Die ring.

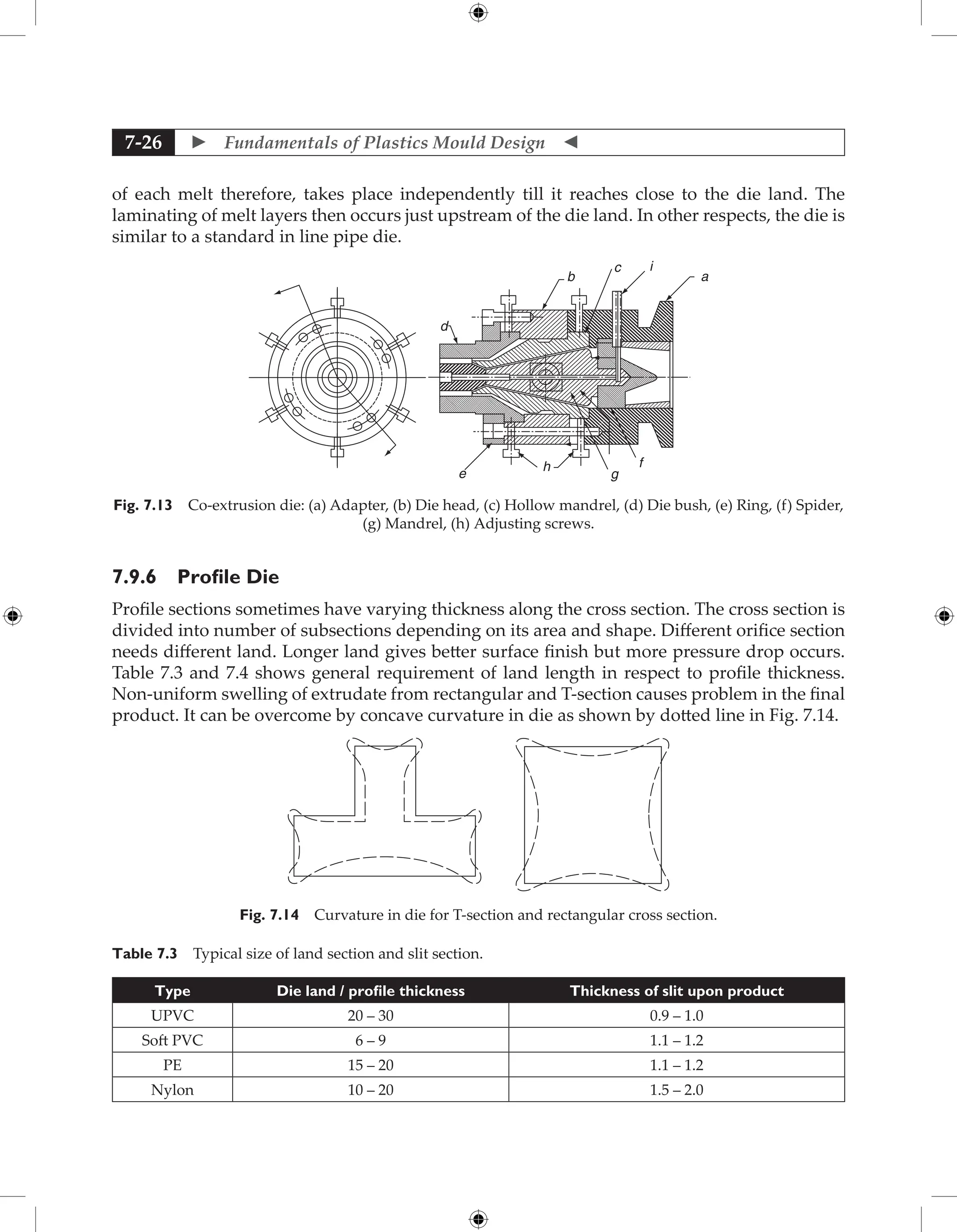

7.9.5 Co-extrusion In-Line Pipe Die

Co-extrusion dies extrude pipes with two layers of different materials, by use of special dies,

which are fed from two separate extruders. The melts from the extruders are supplied to

different manifolds in the die. These manifolds are usually placed at an angle of 90°. One of the

manifolds is in line with one of the screw extruder, while the other feeds the material similar

to a cross-head die. The annular flow paths are therefore, provided around two concentric

mandrels. One of the flow paths is between the inner mandrel and the surrounding outer

mandrel and the other flow path is between the outer mandrel and the die body. The flow](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fundamentalsofmoulddesign-231217032858-869d3d7e/75/Fundamentals-of-Mould-Design-lecture-pdf-529-2048.jpg)

![ Fundamentals of Plastics Mould Design

7-44

7.14.2 Low Voltage Resistance Heating

It requires a low voltage electric supply and the heating element made from the relatively

thick wire which has a high specific resistance. The wire is formed into a shape such as a coil

or a zigzag, which can be either located within the die or surrounding it.

7.14.3 Induction Heating

Induction heating is the process in which the heat generated in eddy currents induced by

an alternating current which generates an alternating magnetic field around the conductor.

The heating element consists of a heavy gauge copper wire wound into a former and bound

with tape to form a coil of convenient size. The coil is embedded in or located around the die.

When an alternating current is passed through the coil, eddy currents are included in the die,

resulting in heat generation.

7.14.4 Design of Electric Heaters

The electric heaters used in dies are in the shape of a strip, clamp or cartridge; their capacities

are based on watt density, which is the wattage per unit area. To assess the capacity of

heaters for a die, the amount of heat for bringing the die to the operating temperature in the

required time is primarily determined. Secondly, the amount of heat necessary to maintain

the operating temperature is also determined. Whichever of the two is large will decide the

heater size.

1. Required capacity for bringing the die up to the operating temperature (Ha):

HA = Weight of the die × Specific heat of die material × Rise in temperature

= WDCP (t1 – t2) kilocalories (Kcal)

WD = Weight in kg

CP = Specific heat in Kcal/°C/kg where, t1 and t2 in °C.

If the time required to attain the operating temperature (t1) is T (hours),

then, heater capacity (K.W) (for heating of die) = HA / T × 860

2. Heat losses (HL): Losses due to convection and radiation. If the surface area of the die

is calculated, kilowatts lost through convection and radiation can be calculated. Since the die

is attached to the extruder, losses due to conduction may be neglected.

Average loss during heating up of the die = HL / 2

Heater capacity (K.W.) = (HL / 2 ) / 860

So, heater capacity for bringing the die up to the operating temperature,

including losses (K.W.)

[A] = (HA + HL/2) / 860

Total losses during operation (K.W.) [B] = HL / 860](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fundamentalsofmoulddesign-231217032858-869d3d7e/75/Fundamentals-of-Mould-Design-lecture-pdf-548-2048.jpg)