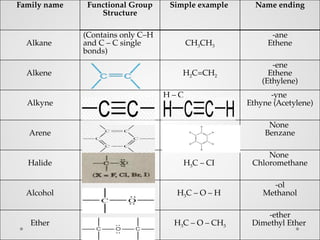

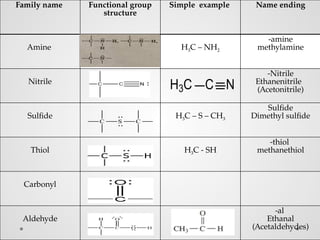

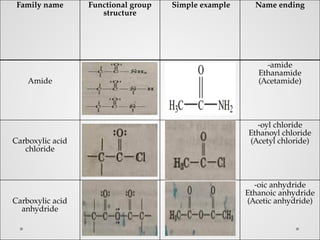

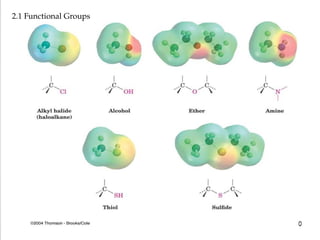

Functional groups are specific groups of atoms that confer characteristic chemical behavior to larger molecules, allowing for the classification of compounds based on reactivity. Examples include alkenes with carbon-carbon double bonds and various other families like alcohols and amines, each characterized by their unique structures. Isomers, which have the same formula but different structures, arise from varying arrangements of these atoms, leading to a diversity of organic compounds.