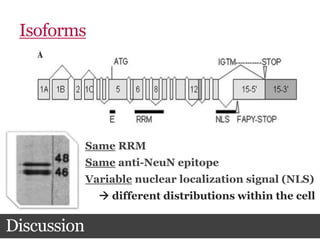

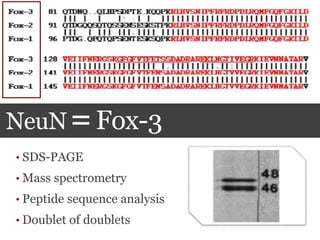

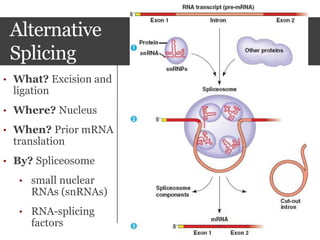

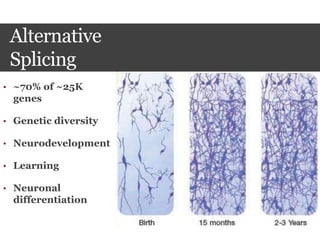

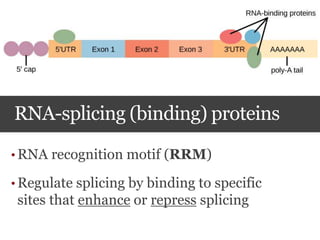

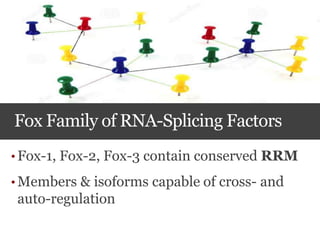

This document summarizes research on the subcellular distribution of the RNA-splicing factor NeuN/Fox-3 in Alzheimer's disease. The study found that in control brains, Fox-3 was largely nuclear, but in Alzheimer's brains it exhibited increased cytoplasmic localization. This may be due to alternative splicing of Fox-3 isoforms with different nuclear localization signals. The results suggest that stress factors in Alzheimer's disease may affect the subcellular distribution of Fox-3 and disrupt its RNA-splicing activity, contributing to disease pathogenesis.

![Fox-3 as a Phosphoprotein

3. Multiple isoelectric

points (pI) of increasing

acidity

Isoelectric

focusing

• pH

gradient

(-)

,

[H+]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/8ff2c1d5-d744-41eb-acc4-f52a8a1d30a4-160612200913/85/FINALBIOCHEMCAPSTONEPP-20-320.jpg)