This document provides information about the 4th Annual LIN Conference, including the conference theme, sub-themes, and details about the conference organizers.

The conference theme is "Enhancing the Learning Experience: Learning for an Unknown Future". It will focus on the first year experience, diversity of the learner experience, and staff development for learning and innovation in teaching.

LIN (Learning Innovation Network) is the conference organizer. It was established in 2007 with the goal of enhancing learning and teaching across Irish Institutes of Technology through collaboration. LIN receives funding from the Strategic Innovation Fund to support its academic professional development activities.

![“Have you found student performance has improved?”

“It's because it's such a massive area that keeping track of the resources /tools is crucial, it

seems to me.”

“That’s what I'm hoping for that they (students) interact outside the 2hr class/lab”

Given that “effective teachers are by definition reflective practitioners” (Kapranos, 2007, p8),

the group was also invited to reflect on whether they could (or would) incorporate social

media into the delivery or assessment of their individual subject areas. At the end of the

module, the participants were asked if the discussion on / use of social media tools during

the TEL module to help [them] gain a better understanding of these?

“Absolutely! Exposure to the range of tools and potential of these from an educational

perspective was great. To hear the experience of participants who had used some of the

social media tools was useful.”

“The TEL module definitely inspired me to explore the world of social media, and although I

know I’m only at the tip of the iceberg I have actually begun using it more.”

“Have I gained a better understanding yes, I would have been familiar with a lot of the tools

but to actually use them no. It may be just me, but I didn't use the blog after the course, I

think it depends on the person. I'm not usually a forum person (usually a lurker...) but I liked

helping out some of the other participants with problems.[…]

[…] the discussion of social media did help me understand social media better.

Finally, they were asked if they had actually used any social media activities into their

teaching since completion of the module.

“I am using Moodle blogs/journal and Moodle discussion forums. I also use YouTube. Have

not ventured into twitter/Facebook etc. as I do not think these are used for work purposes

(personal opinion!) by our students and they are already distracted enough!”

“I now routinely use YouTube clips in class. Whereas before I might have vaguely mentioned

it to the students, now I use the clips as a learning tool.

I now use forums on Moodle, routinely for news and information, Q&A, but this year I’m also

using them for formative assessment.

One of my lab groups are using a Wordpress blog to write up a lab report.

And finally I use Twitter for my own research. One of the big issues I had before was trying

to keep up with the most current research in my area, now I get tweets from the main

players so I feel like I am part of the action again. As tweets are so concise I find that I can

scan through them easily and decide what I want to investigate further when I have the

chance.”

“[…] I'm afraid I haven't been very innovative this semester - more of the same stuff -

Forums, Journal etc. […]I have to say I am not a great fan of Facebook. If you haven't

checked in in a couple of days, it doesn't show you ALL the activity. . If only people would

move over to Google Plus...”

“No would be the answer. […]I did put a help forum on my moodle page for each of my

classes, but so far no posts. Some of the activities on social networking don't lend themselves

to some engineering courses, my subject are mathematical (programming etc.) so getting

20](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/finalproceedings-130122062959-phpapp02/85/2011-Conference-Proceedings-Enhancing-the-learning-experience-Learning-for-an-unknown-future-Barnett-2004-21-320.jpg)

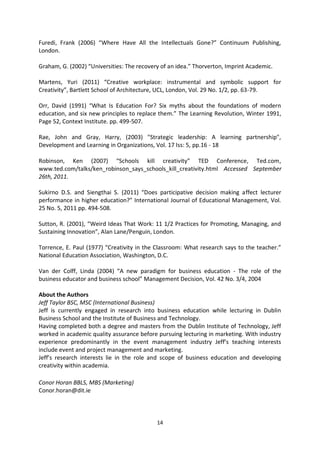

![Again, it is interesting to note that in most cases students were in favour of using these new

channels within an educational context, with both social networks (52%) and online videos

(62%) garnering most support.

Conclusion

Our educational system exists within an ever-changing social and economic environment. In

Ireland, the National Strategy for Higher Education (NSHE) was borne out of a need for

rationalisation and will shape our educational system of the future. This report makes

reference to the role that technology will play in the ‘institutional change’ to come. Bradwell

(2009), quoted in the NSHE, 2011, p.48, suggests that “the internet, social networks,

collaborative online tools that allow people to work together more easily, and open access to

content are both the cause of change for universities, and a tool with which they can

respond”.

Over the course of our professional lives as educators, the tools we will use to reach our

students will change a number of times, yet each tool will be approached with caution, until

its usefulness within education is clearly identified. But for now our generation of students

is, to quote Jimmy Wales, founder of Wikipedia, “WTF – Wiki Twitter Facebook”.

References

Amas (2011) State of the Net. [Internet], 21. Available from: http://amas.ie/online-

research/state-of-the-net/state-of-the-net-issue-21-summer-2011/7-mobile/ [Accessed 10th

October, 2011].

Baird D. and Fisher M. (2005) Neo-millennial user experience design strategies: utilizing

social networking media to support "always on" learning styles. Journal of Educational

Technology Systems, 34 (1), pp. 5 – 32.

24](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/finalproceedings-130122062959-phpapp02/85/2011-Conference-Proceedings-Enhancing-the-learning-experience-Learning-for-an-unknown-future-Barnett-2004-25-320.jpg)

![Bradwell, Peter. (2009) The Edgeless University – Why Higher Education must Embrace

Technology London: Demos 2009, p.8. See http://

www.jisc.ac.uk/media/documents/publications/edgelessuniversity.pdf. Quoted in

Department of Education. (2011) National Strategy for Higher Education to 2030 [ONLINE]

Available at: http://www.hea.ie/files/files/DES_Higher_Ed_Main_Report.pdf. [Accessed 18

November 2011]

Bloom’s digital taxonomy concept map [Online image]. Available from: <

http://edorigami.wikispaces.com/Bloom%27s+Digital+Taxonomy >

Forment, M. (2007) A Social Constructionist Approach to Learning Communities: Moodle. In:

Lytras, M and Ambjörn Naeve. ed. Open Source for Knowledge and Learning Management:

Strategies Beyond Tools. London, Idea Group Publishing, pp.369- 380.

Kaplan A., and Haenlein, M. (2010) Users of the world, unite! The challenges and

opportunities of social media. Business Horizons 53 (1), pp.59-68.

Kapranos, P. (2007) 21st Century Teaching & Learning Kolb Cycle & Reflective Thinking as

part of teaching, creativity, innovation, enterprise and ethics to engineers. In: International

Symposium for Engineering Education, 2007, Dublin. Dublin, Dublin City University, pp.3-11.

Learning Innovation Network Flexible Pathway to Progression [Online image]. Available

from: <http://www.linireland.com/lin-pg-diploma.html>

Morrison, C. (2011) An In-Depth Look at the Social Gaming Industry’s Performance and Prospects on

Facebook [Online]. Available at: http://www.insidefacebook.com/2011/01/24/an-in-depth-look-

at-the-social-gaming-industry%E2%80%99s-performance-and-prospects-on-facebook/

[Accessed 9 October 2011].

Nelson, P. (2010) From Friendster To MySpace To Facebook: The Evolution and Deaths Of

Social Networks [Online]. Available at:

http://www.longislandpress.com/2010/09/30/from-friendster-to-myspace-to-facebook-the-

evolution-and-deaths-of-social-networks/ [Accessed 12th October 2011].

Priego, E. (2011) How Twitter will revolutionise academic research and teaching. Higher

Education Network 12 September [Internet blog]. Available from: <

http://www.guardian.co.uk/higher-education-network/blog/2011/sep/12/twitter-

revolutionise-academia-research > [Accessed 21 October 2011]

Social Media Landscape. (2008) [Online image]. Available from:

<http://www.fredcavazza.net/2008/06/09/social-media-landscape/ > [Accessed 10th

October 2011].

25](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/finalproceedings-130122062959-phpapp02/85/2011-Conference-Proceedings-Enhancing-the-learning-experience-Learning-for-an-unknown-future-Barnett-2004-26-320.jpg)

![Watters, A. (2010) Number of Virtual World Users Breaks 1 Billion, Roughly Half Under Age

15 [Online]. Available at:

http://www.readwriteweb.com/archives/number_of_virtual_world_users_breaks_the_1_bi

llion.php [Accessed 12th October 2011].

Prensky, M. (2001) Digital Natives, Digital Immigrants. On the Horizon, 9 (5) October, pp. 1-

6.

_______________________________________________________

Shared Social Video in Higher Education ‘Blended’ Business Programmes

Denis Cullinane

Dun Laoghaire Institute of Art Design and Technology

Introduction

The term ‘Web 2.0’ was first used by O’Reilly Media (O'Reilly, 2005) as a means of capturing

the evolution of the web to what has also been called the ‘read/write web’ or ‘the social

web’. ‘Web 2.0’ is used to describe web applications and services such as blogs, wikis, social

bookmarking/tagging, content management and collaboration, social networking sites,

virtual worlds and digital media sharing sites such as Flickr and YouTube. ‘Web 2.0’ or ‘Social

Web’ is being increasingly used internationally in nearly all areas of higher education,

including academic, administrative and support areas (Franklin & Armstrong, 2008).

YouTube has been one of the most successful media sharing ‘Web 2.0’ sites since its

inception in April 2005, and is estimated to have more than 1bn ‘views’ of its video content

per day. Many media outlets and educational institutions now have dedicated channels on

YouTube for their video content.

Although YouTube is primarily perceived as an entertainment video site, it has a growing

volume of educational video content posted by educators, students and professionals from

all sectors of business and education. It was this ever growing number of ‘educational

videos’ on YouTube and other video sharing sites like Vimeo, TED, and Blip TV that

contributed to the impetus for this study. This research was conducted to explore the

student experience of using ‘Web 2.0’ or social media shared video in blended business

education. Approximately 155-160 videos from digital media sharing sites were used to

introduce emerging Internet and new media applications and technologies to business,

enterprise and arts management students. The majority of the videos were from social

media sharing sites such as YouTube, TED, and Blip TV. The videos were used extensively in

the classroom and online in the Blackboard Virtual Learning Environment (VLE).

There were two objectives for this study:-

To explore the use of shared social media videos as part of an eLearning

resource in a blended business classroom scenario.

26](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/finalproceedings-130122062959-phpapp02/85/2011-Conference-Proceedings-Enhancing-the-learning-experience-Learning-for-an-unknown-future-Barnett-2004-27-320.jpg)

![—. 2008. YouTube Anchors and Enders: The Use of Shared Online Video Content as a Macrocontext

for Learning. PublicationShare. [Online] 23rd March 2008. [Cited: 13th June 2010.] Paper presented

at the American Educational Research Association (AERA) 2008 Annual Meeting, New York, NY..

http://www.publicationshare.com/SFX7EED.pdf.

Cann, Alan J. 2007. Podcasting is Dead. Long Live Video. Bioscience Education eJournal. [Online]

2007. [Cited: 18th August 2010.] http://www.bioscience.heacademy.ac.uk/journal/vol10/beej-10-

C1.pdf.

—. 2007. Podcasting is Dead. Long Live Video. Bioscience Education eJournal. [Online] 2007.

http://www.bioscience.heacademy.ac.uk/journal/vol10/beej-10-C1.pdf.

Carvin, A. 2007. Learning now:At the crossroads of Internet culture and education. YouTube 101: Yes

it's a real class. [Online] 18 September 2007. [Cited: 20 August 2010.]

Classroom response systems: a review of the literature. Fies, C. and Marshall, J. 2006. 2006, Journal

of Science Education and Technology.

Clickers in the large classroom: current research and best practice tips. . Caldwell, J. 2007. 2007, Life

Sciences Education, pp. 9-20.

Cloudworks: Social Networking for learning design. Conole, Gráinne, et al. 2008. Melbourne :

Ascilite, 2008. Proceedings ascilite Melbourne 2008. pp. 187-196.

Cognitive Pronciples of multimedia learning: The role of modality and contiguity. Moreno, R and

Mayer, R E. 1999. 1999, Journal of Educational Psychology, Vol. 91, pp. 358-368.

Cohen, J. W. 1988. Statistical Power Analysis for the behavioural sciences. Hillsdale, NJ : Lawrence

Erlbaum Associates, 1988.

Cohen, L, Mannion, L and Morrison, K. 2007. Research Methods in Education. New York : Routledge,

2007.

Committee of Inquiry into the Changing Learner Experience. 2009. Higher Education in a Web 2.0

World. London : The Committee of Inquiry into the Changing Learner Experience, 2009. p.

www.clex.org.uk.

Deal, A. 2007. Teaching with Technology White Paper: Podcasting. Educause CONNECT. [Online]

2007. [Cited: 10 August 2010.] http://connect.educause.edu/files/CMU_Podcasting_Jun07.pdf.

'Disruptive technologies', 'pedagogical innovation': What's new? Findings from an in-depth study of

students' use and perception of technology. Conole, Grainne, et al. 2008. 2, 2008, Computers and

Education, Vol. 50, pp. 511-524. Available online www.sciencedirect.com.

Conole, Grainne, et al. 2007. 2007, Computers and Education, pp. 511-524.

Dunn, S. 2003. Return to SENDA? Implementing accessibility for disabled students in virtual learning

environments in UK further and higher education. Sara Dunn VLE Report. [Online] 2003. [Cited: 27th

August 2010.] http://www.saradunn.net/VLEreport/documents/VLEreport.pdf.

32](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/finalproceedings-130122062959-phpapp02/85/2011-Conference-Proceedings-Enhancing-the-learning-experience-Learning-for-an-unknown-future-Barnett-2004-33-320.jpg)

![2009. Effective Use of Virtual Learning Environments. JISC infoNet. [Online] 2009. [Cited: 27th August

2010.] http://www.bisinfonet.ac.uk/InfoKits/effective-use-of-VLEs/intro-to-VLEs/introtovle-moving-

forward/introtovle-issues.

E-Learning: The Hype and the Reality. Conole, G. 2004. 12, 28th Sept 2004, Journal of Interactive

Media in Education. www- jime. open. ac. uk/ 2004/ 12].

Engaging the YouTube Google-Eyed Generation: Strategies for Using Web 2.0 in Teaching and

Learning. Duffy, Peter. 2008. 2008, Electronic Journal of e-Learning, pp. 119-130. available online at

www.ejel.org.

Evaluating the learning in learning objects. Kay, Robin H and Knaack, Liesel. 2007. 2007, Open

Learning, Vol. 22, pp. 5-28.

Exploring the synergy between pedagogical research, teaching and learning in introducotry physics.

Wallace, L. 2010. Dublin : NAIRTL, 2010. LIN Conference: Flexible Learning.

Facilitating an authentic learning experience in introductory physics at the Limerick Institute of

Technology. Wallace, L. and Boyle, L. 2010. Dublin : Castel, 2010. SMEC2010: Inquiry based learning:

facilitating authentic learning experiences in science and mathematics. pp. 19-24.

Factors Influencing the Usage of Websites. Heijden, van der H. 2003. 2003, Netherlands Information

and Management, Vol. 40, pp. 541-549.

Faculty Perceptions on the Use of Video in a Hybrid Faculty Orientation Course. Arakaki, Margret.

2009. Hawaii : Technology Colleges Community (TCC) Worldwide Online Conference, 2009. TCC

Proceedings 2009. pp. 1-5.

Felder, R. 2011. Learning Styles. Resources in Science and Engineering Education. [Online] 14 August

2011. [Cited: 10 September 2011.]

http://www4.ncsu.edu/unity/lockers/users/f/felder/public/Learning_Styles.html.

Franklin, T and van Harmelen, M. 2007. Web 2.0 for Content for Learning and Teaching in Higher

Education. UK. s.l. : JISC, 2007.

Franklin, Tom and Armstrong, Jill. 2008. A review of current and developing international practice in

the use of social networking (Web 2.0) in higher education. Manchester : Frankling Consulting &

CLEX, 2008.

Franklin, Tom and van Harmelen, Mark. 2007. Web 2.0 for Content for Learning and Teaching in

Higher Education. UK : JISC, 2007.

From Silent Film to YouTube: Tracing the Historical Roots of Motion Picture Technologies in

Education. Snelson, Chareen and Perkins, Ross. 2009. 2009, Journal of Visual Literacy, Vol. 28, pp. 1-

27.

Graham, C. 2006. Blended learning systems. Definitions, current trends and future directions. [book

auth.] C Bonk and C Graham. The handbook of blended learning: Global persoectives, local designs.

San Francisco : John Wiley and Sons, 2006.

33](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/finalproceedings-130122062959-phpapp02/85/2011-Conference-Proceedings-Enhancing-the-learning-experience-Learning-for-an-unknown-future-Barnett-2004-34-320.jpg)

![—. 2006. Blended learning systems. Definitions, current trends and future directions. [book auth.] C

Bonk and C Graham. The handbook of blended learning: Global persoectives, local designs. San

Fransico : John Wiley and Sons, 2006.

Guardian Online. 2010. University guide: Open University Our at-a-glance guide to the Open

University. Guardian.co.uk/education. [Online] 8 June 2010. [Cited: 9 June 2010.]

http://www.guardian.co.uk/education/2009/may/10/universityguide-open-uni.

Heller, P. and Heller, K. 1999. Cooperative Group Problem solving in physics. University of

Minnesota Physics Education Research and Development. [Online] 1999. [Cited: 10 September 2009.]

http://groups.physics.umn.edu/physed/Research/CGPS/GreenBook.html.

How are universities involved in blended instruction? Oh, Eunjoo and Park, Suhong. 2009. 3, 2009,

Educational Technology and Society, Vol. 12, pp. 327-342.

Interactive engagement vs traditional methods: a six-thousand student survey of mechanics test data

for introductory physics courses. Hake, R. R. 1998. 1998, American Journal of Physics.

JISC. 2008. Evaluation the Tanglible Benefits of E-learning. Newcastle : JISC, 2008.

Jones, S. 2002. Pew Internet & American Life Project. The Internet Goes to College: How students are

living in the future with today's technology. [Online] 15 September 2002. [Cited: 21 August 2010.]

http://www.pewinternet.org/~/media//Files/Reports/2002/PIP_College_Report.pdf.pdf.

Jumping on the YouTube bandwagon? Using digital video clips to develop personalised. Burden,

Kevin and Atkinson, Simon. 2007. Singapore : s.n., 2007. ASCILITE. p. Poster.

Jumping on the YouTube bandwagon? Using digital video clips to develop personalised learning

strategies. Burden, Kevin and Atkinson, Simon. 2007. s.l. :

http://www.ascilite.org.au/conferences/singapore07/procs/burden-poster.pdf, 2007. In

ICT:Providing choices for learners and learning. Proceedings ascilite Singpore 2007. pp. 96-98.

Just in Time Teaching: active learner pedagogy with www. Novak, G. and Patterson, E. 1998.

Cancun, Mexico : s.n., 1998. International conference on computers and advanced technology in

eduation.

Keelan, Jennifer. 2007. YouTube as a Source of Information on Immunization: A Content Analysis.

Journal of American Medical Asociation. [Online] 5 December 2007. [Cited: 13th June 2010.]

http://jama.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/full/298/21/2482.

Keelan, Jennifer;. 2007. YouTube as a Source of Information on Immunization: A Content Analysis.

Journal of American Medical Asociation. [Online] 5 December 2007. [Cited: 13th June 2010.]

http://jama.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/full/298/21/2482.

Keller, J. 2006. Motivational Design. ARCS Model. [Online] 2006. [Cited: 29 August 2011.]

www.arcsmodel.org.

Knight, R. D. 2002. An instructors guide to introductory physics. San Fransisco, CA : Addison Wesley,

2002.

34](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/finalproceedings-130122062959-phpapp02/85/2011-Conference-Proceedings-Enhancing-the-learning-experience-Learning-for-an-unknown-future-Barnett-2004-35-320.jpg)

![Kristen Purcell. 2010. State-of-Online-Video . Pew Internet and American Life Project. [Online] 3rd

June 2010. [Cited: 10th June 2010.] http://pewinternet.org/Reports/2010/State-of-Online-

Video.aspx.

Kuhlmann, Tom. 2009. The rapid elearning Blog-Are Your E-Learning Courses Pushed or Pulled?

Articulate. [Online] 19 May 2009. [Cited: 21 October 2011.] http://www.articulate.com/rapid-

elearning/are-your-e-learning-courses-pushed-or-pulled.

Laurillard, D. 1993. Rethinking university teaching. A framework for the effective use of educational

technology. London : Routledge, 1993.

Learner and Instructioal Factors Influencing Learner Outcomes within a Blended Learning

Environment. Lim, Hun Doo and Morris, Lane Michael. 2009. 4, 2009, Educational Technology and

Society, Vol. 12, p. 282 293.

—. Lim, Hun Doo and Morris, Lane Michael. 2009. 2009, Educational Technology and Society, p. 282

293.

Learning online: a review of recent literature in a rapidly expanding field. Williams, C. 2002. 3, 2002,

Journal of Further and Higher Education, Vol. 26.

Learning to think like a physicist: a review of research based instructional strategies. Van Heuvelen,

A. 1991. 1991, American Journal of Physics, pp. 891-897.

LeCompte, M and Preissle, J. 1993. Ethnography and Qualitative Design in Educational Research.

London : Academic Press, 1993.

—. 1993. Ethnography and Qualitative Design in Educational Research. 2nd . London : Academic

Press, 1993. p. 108.

Lorencova, Viera. 2008. YouTube Dilemmas: The Appropriaton of User-Generated Online Videos in

Teaching and Learning. Currents in Teaching and Learning. Fall, 2008, Vol. 1, 1, pp. 62-71.

—. 2008. YouTube Dilemmas: The Appropriaton of User-Generated Online Videos in Teaching and

Learning. Currents in Teaching and Learning. Fall, 2008, Vol. 1, 1.

Marsh II, G E, McFadden, A C and Price, B P. 2004. Blended Instruction: Adapting conventional

instrument for large classes. The Univerisity of Alabama : Institute for Interactive Technology, 2004.

Mayer, R E and Moreno, R. 1998. A cognitive theory for multimedia learning:Implications for design

principles. [Online] 1998. [Cited: 10 August 2010.] http://www.unm.edu/~moreno/PDFS/chi.pdf.

—. 2002. Animation as an aid to multimedia learning. Educational Psychological Review. 2002, Vol.

14, 1, pp. 87-99.

Mayer, R E. 2001. Multimedia Learning. New York : Cambridge University Press., 2001.

Mazur, E. 1997. Peer Instruction. New Jersey : Prentice Hall, 1997.

35](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/finalproceedings-130122062959-phpapp02/85/2011-Conference-Proceedings-Enhancing-the-learning-experience-Learning-for-an-unknown-future-Barnett-2004-36-320.jpg)

![Meaningful Learning with Digital and Online Videos: Theoretical Perspectives. Karppinen, Paivi.

2005. 2005, Association for the Advancement of Computing in Education (AACE) Journal, pp. 233-

250.

Micolich, Adam. 2008. How I learned to stop worrying and love YouTube. University World News.

[Online] 2008. [Cited: 13th June 2010.]

http://www.universityworldnews.com/article.php?story=20081127124726106.

Mixed Methods Research: A Research Paradigm Whose Time Has Come. Burke Johnson, R and

Onwueguzie, Anthony J. 2004. 7, 2004, Educational Researcher, Vol. 33, pp. 14-26.

New Approaches, new vision: capturing teacher experiences in a brave new online world. Connolly,

Michael, Jones, Cath and Jones, Norah. 2007. 1, 2007, Open Learning, Vol. 22, pp. 43-56.

No single cause: Learning gains, student attitudes, and the impacts of multiple effective reforms.

Pollock, S. J. 2004. 2004. Physics Education Research Conference.

O'Reilly, T. 2005. What is Web 2.0? O'Reilly Media. [Online] 2005. [Cited: 9th August 2010.]

http://oreilly.com/web2/archive/what-is-web-20.html.

Purcell, K. 2010. State-of-Online-Video. Pew Internet and American Life Project. [Online] 3rd June

2010. [Cited: 10th June 2010.] http://pewinternet.org/Reports/2010/State-of-Online-Video.aspx.

Purcell, Kristen. 2010. State-of-Online-Video. Pew Internet and American Life Project. [Online] 3rd

June 2010. [Cited: 10th June 2010.] http://pewinternet.org/Reports/2010/State-of-Online-

Video.aspx.

Reconstructing Technoliteracy: a multiple literacies approach. Kahn, K and Kelner, D. 2005. 3, 2005,

E-Learning, Vol. 2, pp. 238-251.

Redish, E. F. 2003. Teaching Physics with the Physics Suite. Hobokern, NJ : John Wiley & Sons, Inc,

2003.

Replicating and understanding successful innovations: Implementing tutorials in introductory physics.

Finkelstein, N. D. and Pollock, S. J. . 2005. 2005, Physical Review Special Topics - PER, pp. 1-13.

RL-PER1: Resource letter on physics education research. McDermott, L. C. and Redish, E. F. 1999.

1999, Te American Journal of Physics.

Rossett, A, Douglis, F and Frazee, R. 2003. Strategies for building blended learning. Learning Circuits.

[Online] 2003. [Cited: 9th June 2010.] http://www.essentiallearning.net/news/Strategies for Building

Blended Learning.pdf.

Saettler, P. 2004. The evolution of American educational technology. . Greenwich : CT: Information

Age Publishing, 2004.

Screen design: a location of information and its effects on learning. Aspillagae, M. 1991. 3, 1991,

Journal of Computer-Based Instruction, Vol. 18, pp. 89-92.

36](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/finalproceedings-130122062959-phpapp02/85/2011-Conference-Proceedings-Enhancing-the-learning-experience-Learning-for-an-unknown-future-Barnett-2004-37-320.jpg)

![MILLS, J. E. & TREAGUST, D. F. 2003. Engineering Education - is Problem-Based or Project-

Based Learning the Answer? Australasian Journal of Engineering Education., online

publication, 04, 1-16.

MORENO-ARMELLA, L. & WALDEGG, G. 1993. Constructivism and mathematical education.

International Journal of Mathematical Education in Science and Technology, 24, 653-661.

MURPHY, R. 2006. Evaluating New Priorities for Assessment. In: BRYAN, C. & CLEGG, K.

(eds.) Innovative Assessment in Higher Education. London: Routledge.

NCTM. (2009). The National Council of Teachers of Mathematics. Retrieved 19th November

2009, from http://standards.nctm.org/document/chapter2/index.htm

OLDFIELD, N. & ROSE, C. 2004. Learning delivers the best return. Industrial and Commercial

Training, 36, 25-28.

PBLE-GUIDE 2003. A Guide to Learning Engineering Through Projects. In: NOTTINGHAM, U.

O. (ed.) Project Based Learning in Engineering.

ROBINSON, A. & UDALL, M. 2006. Using formative assessment to improve student learning

through critical reflection In: BRYAN, C. & CLEGG, K. (eds.) Innovative Assessment in Higher

Education. London: Routledge.

RUST, C. 2002. The impact of assessment on student learning. Active Learning in Higher

Education, 3, 145-158.

SCHACHTERLE, L. & VINTHER, O. 1996. The Role of Projects in Engineering Education.

European journal of Engineering Education, 21, 115-120.

SEFI. 2005. European Society for Engineering Education - Mission Statement [Online].

Available:

http://www.sefi.be/wp-content/uploads/SEFI%20Mission%20Statement%2016.09.05.pdf

[Accessed 29th November 2009].

STAUFFACHER, M., WALTER, A. I., LANG, D. J., WIEK, A., & SCHOLZ, R. W. (2006). Learning to

research environmental problems from a functional socio-cultural constructivism

perspective. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education, 7(3), 252-275.

STEWART, R. A. 2007. Investigating the link between self directed learning readiness and

project-based learning outcomes: the case of international Masters students in an

engineering management course. European Journal of Engineering Education, 32, 453-465.

STIPEK, D. J., GIVVIN, K. B., SALMON, J. M., & MACGYVERS, V. L. (2001). Teachers' beliefs and

practices related to mathematics instruction. Teaching and Teacher Education, 17, 213-226.

87](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/finalproceedings-130122062959-phpapp02/85/2011-Conference-Proceedings-Enhancing-the-learning-experience-Learning-for-an-unknown-future-Barnett-2004-88-320.jpg)

![The study showed that many in the class had engaged in a high level of critical thinking and

this had in turn led to a high level of debate and subsequent learning in class. It was notable

that the perspectives of many in the class had changed as their confidence grew. The

students’ initial fear in their first year of adult education had by the end of the second year

been replaced by a curiosity and high level of critical thinking and reflection (Mezirow,

1991).

Of note were the students’ criticisms of teaching methods employed and of their need to be

heard in this regard. The tutor meanwhile has a role beyond imparting information to

others. Particularly with a class where there is quite a wide range of educational experience

it is imperative that the tutor is mindful of Knowles’ concept of assisting the learner satisfy

the educational need, at whatever level they are struggling.

References

Alheit P., (1994), The Biographical Question’ as a challenge to Adult Education, International

Review of Education vol. 40 no 3-5, pp. 283-298

Antikainen A., (1998) Between Structure and Subjectivity: Life-Histories and Lifelong

Learning, Manuscript for International Review of Education, Vol. 44 no.2-3, pp. 215-234.

Antikainen A., Houtsonen J., Kauppila J., & Turunen A., (1993) In Search of the Meaning of

Education: The Case of Finland, Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, vol. 39, no. 4

Aslanian, C. B., & Brickell, H. M. (1980) Americans in transition: Life changes as reasons for

adult learning. New York: College Entrance Examination Board.

Baxter P. & Jack S. (2008) Qualitative case study methodology: Study design and

implementation for novice researchers, The Qualitative Report, vol. 13, no. 4, 544-559.

Available :http;//nova.edu/sss/QR/QR13-4/Baxter.pdf

[Accessed on Mar 3 2010]

Belenky M. F., Clinchy B. Mc., Goldberger N. R., and Tarule J. M. (1986) Women’s Ways of

Knowing, The Development of Self, Voice and Mind, New York, Basic Books.

Bhattacharya K. & Han, S. (2001) Piaget and cognitive development, In M. Orey (Ed.),

Emerging perspectives on learning, teaching, and technology.

Available: http://projects.coe.uga.edu/epltt/

[Accessed on Feb. 6. 2010]

Bird E. (1999) Lifelines and lifetimes: retraining for women returning to higher level

occupations- policy and practice in the U.K, International Journal of Lifelong Education, vol.

18, no. 3, 203-216.

Cooper S. (2004) Theories of Learning in Educational Psychology: Jack Mezirow:

Transformational Learning Theory, On-line article,

Available : http://www.lifecirclesinc.com/Learningtheories/humanist/mezirow.html

95](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/finalproceedings-130122062959-phpapp02/85/2011-Conference-Proceedings-Enhancing-the-learning-experience-Learning-for-an-unknown-future-Barnett-2004-96-320.jpg)

![[Accessed on Nov 18 2009]

Cranton C. (1994) Understanding and Promoting Transformative Learning, San Francisco,

Jossey-Bass

Creswell J. W. (1994) Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design, Choosing Among Five

Traditions, Sage Publications inc., Thousand Oaks, California.

Creswell J. W. (2007) Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design, Choosing Among Five

Approaches, Sage Publications inc., Thousand Oaks, California.

Cypher A. (1986) Notes on In A Different Voice BY Carol Gilligan,

Available: http;//acypher.com/bookNotes/Gilligan.html.

[Accessed on Nov 22 2009]

Dewey J. (1998) How We Think, Houghton Mifflin Company Boston.

Freire P. (1983) Pedagogy of the Oppressed, 20th anniversary edition, New York, Continuum

publishing company.

Gilligan C. (1982) In a Different Voice, Harvard University Press.

Hanks, W.F. (1991) Forward by William F. Hanks (13-24). Situated Learning: Legitimate

Peripheral Participation, edited by J. Lave and E. Wenger, New York: Cambridge University

Press.

hooks b. (1994) in Burke B. (2004) 'bell hooks on education', the encyclopedia of informal

education. Available : www.infed.org/thinkers/hooks.htm

[Accessed on April 20 2010]

Illeris K. (2003) Adult education experienced by the learners, International Journal of Lifelong

Education, vol. 22, no. 1, Jan-Feb, 13-23.

Inglis T. (1997) Empowerment and Emancipation, Adult Education Quarterly, vol. 48, issue1,

p.3-18.

Jones J. (2007) Connected Learning in Co-operative Education, International Journal of

Teaching and Learning in Higher Education, vol 19, no. 3, 263-273.

Jordan A. Carlile O. and Stack A., (2008) Approaches To Learning, A Guide For Teachers,

McGraw Hill, Open University Press.

Kelly F. (2009) The Psychology of learning; Social Constructivism;

Available: http://webcourses.dit.ie/webct/urw/lc5122011.tp0/cobaltMainFrame.dowebct

[Accessed Nov. 11 2009]

Knowles, M. (1984) Andragogy in Action. Jossey-Bass, San Francisco:

96](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/finalproceedings-130122062959-phpapp02/85/2011-Conference-Proceedings-Enhancing-the-learning-experience-Learning-for-an-unknown-future-Barnett-2004-97-320.jpg)

![Knowles M. (1980) The Modern Practice of Adult Education: From Pedagogy to Andragogy,

Chicago, Follet Publishing Company,

Kolb, D. A. (1984) Experiential Learning, Englewood Cliffs, NJ.: Prentice Hall.

Lave, J. & Wenger, E. (1991) Situated Learning. Legitimate peripheral participation,

Cambridge, University of Cambridge Press,

Lunney M. (2005) Summary of Findings from Women’s ways of Learning, The Development

of Self, Voice and Mind,

Available:

http://media.wiley.com/product_ancillary/17/08138160/DOWNLOAD/3%20findings%20fro

m%20women%20ways%20of%20knowing.doc.

[Accessed on Nov. 26 2009]

Mergel B. May 1998 Instructional design and learning theories,

Available: http://www.usask.ca/education/coursework/802papers/mergel/brenda.htm

[Accesed on Nov. 11 2009]

Mezirow, J. (1978) "Perspective Transformation." Journal of Adult Education, vol. 28 p. 100-

110.

Mezirow J. (1991) Transformative dimensions of adult learning, Jossey-Bass, San Francisco.

Mezirow, J. (1998) On critical reflection, Adult Education Quarterly, [Serial online], Available:

http;//0search.ebscohost.com.ditlib.dit.ie;80/login.aspx?direct=truedb=aph&AN=569549&si

te=ehost-live.

[Accessed on Dec 14 2009]

Patterson, C.H. (1977) Foundations for a Theory of Instruction and Educational Psychology.

Harper and Row, New York.

Piaget, J. (2001) The psychology of intelligence. (Classics Edition), New York: Routledge.

Nederven Pieterese J., (1992), Emancipations, Modern and Postmodern. In Nederven

Pieterese J., (ed.), Emancipations, Modern and Postmodern, London Sage.

Rogers C. and Frieberg H. J., (1994) Freedom To Learn, 3rd ed., Prentice Hall inc Third

Edition, Prentice Hall, Inc., New Jersey

Savicevic D., (1999), Adult Education: From Pedagogy to Theory Building, vol. 27, In Poggler

F., (ed), Studies in Pedagogy, Andragogy, and Gerontagogy, Frankfurt Am Main, Peter Lang.

Soy S. K. (1997) The Case Study as a research Method. Unpublished paper, University of

Texas, Austin. Available: http;//www.ischool.utexas.edu/~ssoy/usesusers/1391dIb.htm.

[Accessed on Mar.17.2010]

97](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/finalproceedings-130122062959-phpapp02/85/2011-Conference-Proceedings-Enhancing-the-learning-experience-Learning-for-an-unknown-future-Barnett-2004-98-320.jpg)

![Stake R. (1995) The Art of Case Study Research, Thousand Oaks, CA, Sage.

Wenger E. (2006) Communities of Practice, A brief introduction,

Available: http://www.ewenger.com/theory/index.htm. [Accessed on Dec. 22 2009]

Wrushen B. and Whitney H. S. (2008) Women secondary school principals: multicultural

voices from the field, International Journal of Qualitative studies in Education, vol. 21, no. 5,

457-469.

Yin R.K. (2003) Case Study Research; Design and Method, (3rd ed.), Thousand Oaks, CA; Sage

Zucker D. M. (2001) Using Case Study Methodology In Nursing Research, The Qualitative

report [On-Line serial], vol. 6, no. 2.

Available: http://wwwnova.edu/ssss/QR/QR6-2/zucker.html [Accessed on Mar.3 2010]

_______________________________________________________

Learner Experience with the MyElvin Social Network for Practicing

Languages

Darragh Coakley, Maria Murray

Cork Institute of Technology

Introduction

On the 25th of February 2011, a process of non-violent civil resistance begin across Egypt

which would see the resignation of President Mohammed Hosni Mubarak on February 11th,

a mere 2 weeks later. The uprising was fuelled in a large part by the use of social media

tools. One activist noted "We use Facebook to schedule the protests, Twitter to coordinate,

and YouTube to tell the world." (Howard, 2011). Such was the power of social networking

revolution that the Egyptian government shut down internet access for most of the country

on the 27th of January - two days after the uprising began (BBC, 2011). Between August 6

and 10 August 2011, a number of areas in London were subject to rioting and looting. The

use of social media was blamed in the mainstream media as an accelerant and facilitator of

the riots, with some publications labelling those using social media to co-ordinate attacks as

“Twitter rioters” (France & Flynn, 2011). At the same time, Twitter was utilised by some to

help co-ordinate efforts to repair some of the damage done by the rioting under a banner of

“# riotcleanup” (BBC, 2011). As noted by M. Boler: “People are using new media approaches

to intervene in public debate and to try to gain a seat at the table. Central to this has been

the introduction of the sociable web”. (Boler, 2008)

A small number of social networking platforms now count users in the hundreds of millions

and have changed the way in which a generation interacts with other computers. This paper

will examine the experiences of the DEIS Department in the Cork Institute of Technology in

98](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/finalproceedings-130122062959-phpapp02/85/2011-Conference-Proceedings-Enhancing-the-learning-experience-Learning-for-an-unknown-future-Barnett-2004-99-320.jpg)

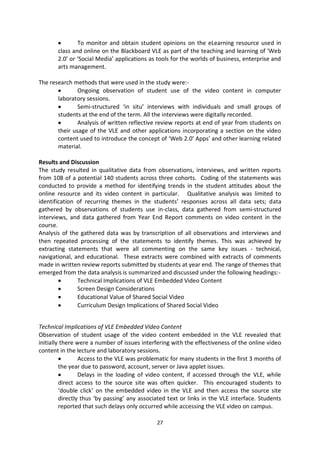

![leaving comments to others students, and replying to comments left on their blog postings

were assessed. No formal rubric for assessing each component has been developed to date.

Pedagogical evaluation:

The student reaction to the blog was captured using a four point Likert rating scale [Strongly

agree, Agree, Disagree, Strongly disagree]. The audience response system ‘Clickers’ from

Turning Technologies was used to record and save the results.

Results

Student feedback:

% %

Section Question Overall Overall

Agree Disagree

Using the software

Using the Webcourses blog software was

easy to use 95 5

I was given sufficient training to be able

to use the software 92 8

My classmates helped me to use the

software 59 41

Feelings towards writing

I enjoyed writing my blog 76 24

and posting the blog

I was anxious about what the other

students would think of my first blog 59 41

I was anxious about what the lecturer

would think of my first blog

78 22

I was comfortable posting my blogs by

the end 97 3

Feedback I found the lecturer feedback comments

on my own first blog was useful to help

me improve 80 20

I found the lecturer feedback comments

on other students blogs was useful to

help me improve 69 31

I found the students comments on my

blogs was useful to help me improve 64

session 36

I found reading other students blogs

helped me write better blogs

report 86 14

111](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/finalproceedings-130122062959-phpapp02/85/2011-Conference-Proceedings-Enhancing-the-learning-experience-Learning-for-an-unknown-future-Barnett-2004-112-320.jpg)

![(CIHE) and 12 of the Subject Centres in the Higher Education Academy Learning and

Teaching Support Network (LTSN)]

DOEST, Australian Government (2006) Employability Skills from Framework to Practice

Bates P, Tyers C, Loukas G (2006) The Labour Market for Graduates in Scotland SE1726,

Futureskills Scotland, April

http://www.employment-studies.co.uk/pubs/summary.php?id=se1726

Fallows, S. and Steven C. (2000) Integrating key skills in higher education: employability,

transferable skills and learning for life. Kogan page. London

Hunt, C. (2011) National Strategy for Higher Education to 2030, Report of the Strategy

Group, available from http://www.hea.ie/en/node/1303 Last accessed 18 October

Yorke, M. and Knight, P. (2006), Embedding employability into the curriculum, No. 3 of the

ESECT/LTSN Generic Centre "Learning and Employability" series. York: Higher Education

Academy

MacCraith B. (2011) University plans to make its students model graduates, Irish Times,

8September 2011

http://www.irishtimes.com/newspaper/frontpage/2011/0908/1224303702056.html

Condon N and McNaboe J (2011) Monitoring Ireland's Skills Supply - Trends in Education and

Training Outputs. annual report produced by the Skills and Labour Market Research Unit of

FÁS on behalf of the Expert Group on Future Skills Needs. Available from

http://www.skillsireland.ie/publications/2011/title,8222,en.php

_______________________________________________________

Sub-theme 3 – STAFF DEVELOPMENT

Engaging and preparing students for future roles – community-based learning in DIT

Catherine Bates

Dublin Institute of Technology

Abstract

This paper will introduce the principles of Community-Based Learning (CBL), showing how

this pedagogy allows students to use a range of learning methods on real-life projects,

preparing them for a changing professional environment and social context, and enhancing

their college experience. Lecturers and underserved community partners collaboratively

design projects to meet the learning needs of students and to work towards community

goals. Through these curriculum-based projects, students develop greater awareness of

themselves as learners, and of the role of their discipline in society, as well as building a

range of transferable professional skills. This paper will give 2 clear case studies on how

123](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/finalproceedings-130122062959-phpapp02/85/2011-Conference-Proceedings-Enhancing-the-learning-experience-Learning-for-an-unknown-future-Barnett-2004-124-320.jpg)

![modules have been adapted to include this pedagogy in DIT, drawing on three years’

experience of coordinating the Programme for Students Learning With Communities in

Dublin Institute of Technology. Participants will gain a clear sense of what is involved in

using this approach to learning and teaching, and the benefits for their students, as well as

to the participating community partners. They will also have a clear framework for planning

their own projects. Community-based learning (or service-learning) is recommended in the

National Strategy for Higher Education to 2030.

Introduction

In 1897 John Dewey wrote about education: ‘With the advent of democracy and modern

industrial conditions, it is impossible to foretell definitely just what civilization will be twenty

years from now. Hence it is impossible to prepare the [learner] for any precise set of

conditions’. His solution was to activate and combine the learner’s individual talents in

experiential education, in relation to their social context and the service they could offer to

society, from a social justice perspective (Dewey 1897: no page numbers).

The Programme for Students Learning With Communities in the Dublin Institute of

Technology, part of DIT’s Community Links Programme, supports lecturers and students

engaging in community-based learning and research (also known as service-learning, and

science shop), and builds links with communities. ‘Service learning is a teaching and learning

strategy that integrates meaningful community service with instruction and reflection, to

enrich the learning experience, teach civic responsibility and strengthen communities. It is

used in the US in a wide variety of settings, including schools, universities, and community-

based organisations’. (Hunt 2011: 59).

DIT lecturers and/or students work with underserved community partners (local groups,

not-for-profits, etc) to collaboratively develop real-life curriculum-based projects to

enhance students’ learning, as well as working towards community goals. Learning can

come alive for students as they take their subject knowledge out of the lecture theatre and

apply it to real-life projects in various social contexts. These projects require students to

engage in critical reflection and to develop social awareness, and aim to energize them to

work for social change. Through these curriculum-based projects, students develop greater

awareness of themselves as learners, and of the role of their discipline in society, as well as

building a range of transferable professional skills such as communication, social interaction,

teamwork, project management, and problem-solving. The community becomes part of the

teaching process, and the students’ work contributes to the community’s work and goals.

Community-based learning (CBL) ensures that students are actively experiencing, and not

just theorizing on, their discipline in its social context, which also better prepares them for

future life and work. This high-impact pedagogy has been shown to increase student

engagement, transferable skills, and retention (Hurd 2008).

In 2010/11 approximately 1,200 DIT students worked on curriculum-based collaborative

projects with over 100 community partners. One in three undergraduate programmes in DIT

last year offered students the opportunity to work collaboratively with communities. This

124](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/finalproceedings-130122062959-phpapp02/85/2011-Conference-Proceedings-Enhancing-the-learning-experience-Learning-for-an-unknown-future-Barnett-2004-125-320.jpg)

![Case study two

Larger multifaceted community-based learning projects can be suited to incorporation into

work placement modules. Academic staff have been exploring CBL as an alternative to

industrial work placements5. This is recommended in the National Strategy for Higher

Education to 2030 (Hunt 2011: 59): ‘One solution to the challenge of finding suitable work

placement for students is service learning. This has the advantage of also providing students

with the opportunity to engage in civic endeavours.’

Computer Science lecturer Ciarán O’Leary and his students, in partnership with Wells for

Zoe, Camara Education, and DIT’s Computer Learning in Communities (CLiC) Programme,

collaborated on a more complex CBL project, involving a stay in Africa, and a 30-credit work-

placement module. O’Leary has been involved in CBL and CBR projects with his students for

almost ten years, and articulates the benefits for students (O’Leary 2011a):

We see this as an equivalent to work placement, rather than a substitute […] the

service-learning module provides students with an opportunity not available to

them through work placement, for example, to take on more responsibility and

have more control of the direction of their work than they would get in work

placement. The ability to work autonomously, for example, is a learning outcome

that can be better achieved, we suspect, in our module than work placement. The

ability to understand organisational and management structures would be better

served by work placement. The distinction is in the emphasis, though both modules

treat more or less the same high-level learning outcomes.

Combining Ciarán’s views with our own reflection on the relationship between CBL/CBR and

work placement, the following table shows the similarities and differences (in italics)

between them.

Industrial work placement CBL/CBR placement

Develop professional skills and CV Develop professional skills and CV

experience experience

Develop knowledge of organisational and Develop project management and

management structures organisational skills

Learn about industry as potential employer Learn about community/not-for-profit

Develop communication skills with sector as potential employer

colleagues Develop communication skills with clients

Develop understanding of role of discipline Develop understanding of role of discipline

in industry in society

Develop ability to work responsibly in a Develop ability to work autonomously in a

clear line-management structure. flexible management structure.

Table 1: Differences between learning outcomes on industrial work placement and CBL

placement

5

A fuller discussion of the use of CBL/CBR in DIT across a range of disciplines as an alternative to

work placement, including an early assessment of Ciarán O’Leary’s module, can be found in the

following paper: Bates, C. and Gamble, E. (2011) ‘Alternatives to industrial work placement at Dublin

Institute of Technology’, Higher Education Management and Policy Journal, 23 (2).

127](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/finalproceedings-130122062959-phpapp02/85/2011-Conference-Proceedings-Enhancing-the-learning-experience-Learning-for-an-unknown-future-Barnett-2004-128-320.jpg)

![6. Have you any suggestions regarding the improvement of future NEST

programmes?

7. What have you learned about mentoring that might benefit you in future

teaching?

APPENDIX D: QUESTIONNAIRE 2 – POST TEACHING PRACTICE NEST REVIEW

1. Have you succeeded in continuing the NEST meetings by telephone or otherwise

during TP? If so, how many meetings were held and which methods of

communication were used? If not, why not?

2. How effective were these meetings? Did they help you with TP challenges? Give

examples, if appropriate.

3. Was time management an issue for you during NEST while on TP? Explain.

4. How did you find the reflective writing aspect of NEST while on TP (i.e. 6 reflections)?

Elaborate.

5. Would you advise that NEST be used while on TP in future years? Explain your

answer.

6. What was the greatest learning experience for you as a NEST participant and/or

leader?

7. If NEST were to continue in future years what would you suggest?

8. Do you think that the NEST Certificate will be of benefit to you in regards to

employment? Explain.

9. Do you have other comments/suggestions? [Minimum of one please]

10. While acknowledging your contribution as a class, can I, as a researcher, have

permission to write up NEST research findings, with a view to presentation/publication,

and also include digital images/videos of NEST work and participants?

151](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/finalproceedings-130122062959-phpapp02/85/2011-Conference-Proceedings-Enhancing-the-learning-experience-Learning-for-an-unknown-future-Barnett-2004-152-320.jpg)