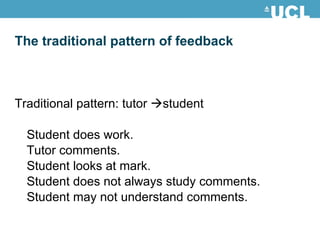

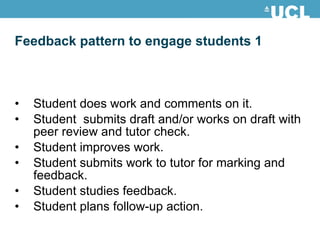

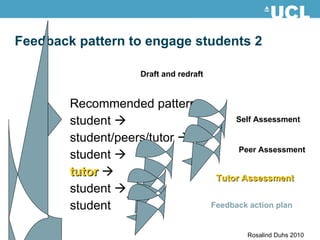

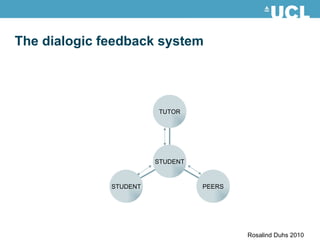

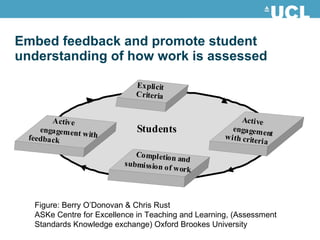

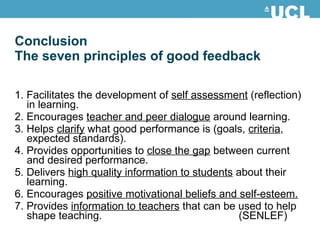

The document discusses effective feedback strategies to promote student learning. It defines feedback broadly as any information students receive about their knowledge and skills. It emphasizes the importance of facilitating dialogue between students, peers, and teachers. It also recommends that students play an active role in assessing their own work and revising it based on feedback before final submission. The goal is to engage students more fully in the feedback process and help them understand how to improve their performance.