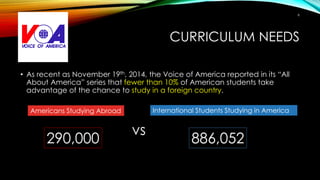

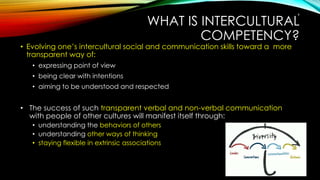

The document outlines an intercultural competencies curriculum aimed at equipping K-12 students in Broward County, Florida, with the skills needed for global citizenship through experiential learning. It identifies gaps in the current educational offerings regarding intercultural competencies and proposes a course that encourages understanding, flexibility, and adaptability across cultures. Additionally, it emphasizes the importance of diversity within classrooms and the need for intentional student selection based on various criteria to foster intercultural exposure.

![CURRICULUM NEEDS:

EXISTING CURRICULUM

• Currently, CPALMS offers a “Multicultural Studies” course, it simply teaches

students the facts of how multiculturalism has impacted American society:

“[T]he chronological development of multicultural

and multiethnic groups in the United States and their

influence on the development of American culture.

Content should include, but is not limited to:

the influence of geography on the

social and economic development

of Native American culture

the influence of major historical

events on the development of a

multicultural American society

a study of the political, economic

and social aspects of Native

American, Hispanic American,

African American and Asian

American culture.”

4](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fajardo-oneworldcurriculum-interculturalcompetence-150119212205-conversion-gate02/85/Global-Citizenship-A-One-World-Curriculum-for-Intercultural-Competence-L-Fajardo-4-320.jpg)

![SUPPORTING LITERATURE (2)

• Mydland, L. (2011, September 15)

The legacy of one-room schoolhouses:

A comparative study of the American Midwest and Norway.

European Journal of American Studies [Online], 6(1), 1-20. doi:10.4000/ejas.9205

• Purpose: a comparative study of the

American Midwest and the country of Norway

exploring the one-room schoolhouse in terms

of the societies’ differing value systems and

the power of the one-room schoolhouse in the

indoctrination of a society’s values.

• Findings/Conculsion: that the American

schoolhouse has been an object of heritage

with high national symbolic values, reflecting

the development of the nation and acting as

the “impetuses in political society” which were

establishing and maintaining national

common values.

14](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fajardo-oneworldcurriculum-interculturalcompetence-150119212205-conversion-gate02/85/Global-Citizenship-A-One-World-Curriculum-for-Intercultural-Competence-L-Fajardo-14-320.jpg)

![SUPPORTING LITERATURE (4)

• Moon, S. (2010)

Multicultural and Global Citizenship in the Transnational Age:

The Case of South Korea

International Journal of Multicultural Education, 12(1), 15. Retrieved 2014, from http://www.ijme-

journal.org/index.php/ijme/article/view/261/392

• Purpose: to demonstrate the paradigm shift necessary in methods of

teaching multicultural citizenship and global citizenship in this world that has

“changed from a space of ‘places’ to a space of ‘flows’…[where] people

residing in the transnational world need to develop new notions of

citizenship.” Moon explains that because the traditional understanding of a

nation-state with its homogenous culture and society has been “challenged

by a transnational population of immigrants,” multicultural education must

now meet that challenge and go beyond the “limited nation-state border

to the global community.”

• Findings: that the “global context [of] educating students to function in one

nation-state does not prepare them for global citizenship” as this would be

“inconsistent with the racial, ethnic, and cultural realities” …as “outside

forces of globalization interrupt the nation-state’s position as the

predominant unit of social organization.”

• Conclusion: in keeping with the founding ideology of Korea in 2333 BC,

which states that “the purpose of Korean education is to cultivate Korean

citizens to contribute to democracy and mutual prosperity of all human

beings,” Korean “educators and policy makers should think about how to

educate citizens that meet the needs of a transnational and cosmopolitan

society.”

16](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fajardo-oneworldcurriculum-interculturalcompetence-150119212205-conversion-gate02/85/Global-Citizenship-A-One-World-Curriculum-for-Intercultural-Competence-L-Fajardo-16-320.jpg)

![LEARNING EXPERIENCES:

WHAT WILL THEY DO?

• To begin, students will learn the conceptual

difference between Multiculturalism Studies and

Intercultural Competencies, thereby grasping the

purpose and goals of this particular year-long

course.

• Next, students will begin by choosing a target

culture and its language. [Note: whereas

proficiency in a second language would

complement the student’s experience, it will not be

a curriculum pre-requisite.]

• For the target culture, learners will:

1) explore its Family, Education, Law and Order or

Power and Politics;

2) gather material outside the classroom in relation

with these cultural topics;

20](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fajardo-oneworldcurriculum-interculturalcompetence-150119212205-conversion-gate02/85/Global-Citizenship-A-One-World-Curriculum-for-Intercultural-Competence-L-Fajardo-20-320.jpg)