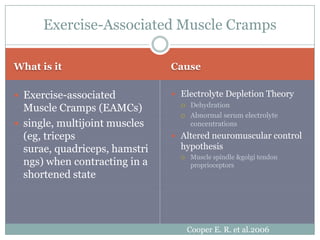

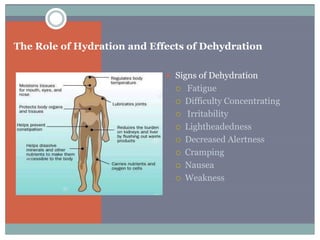

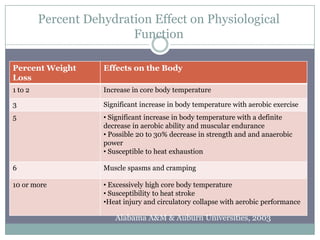

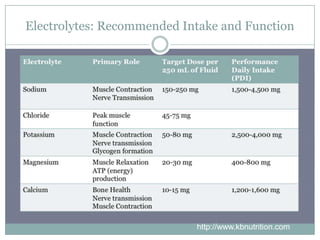

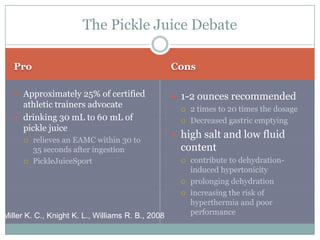

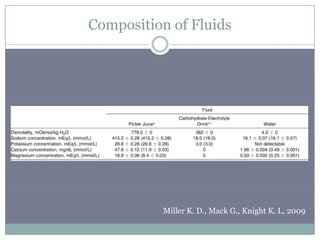

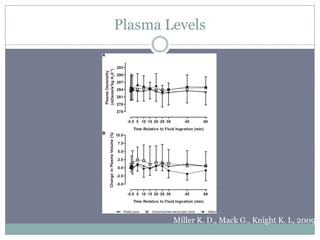

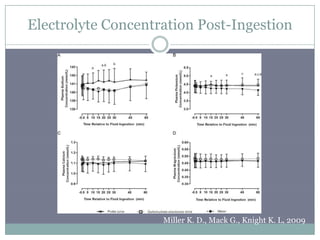

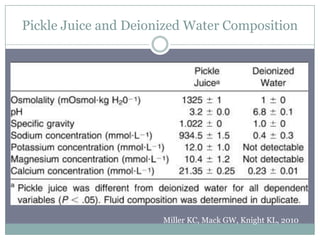

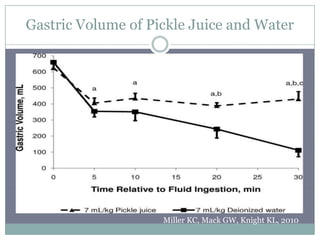

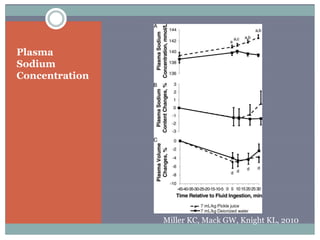

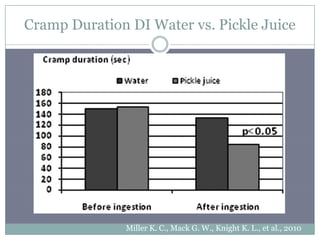

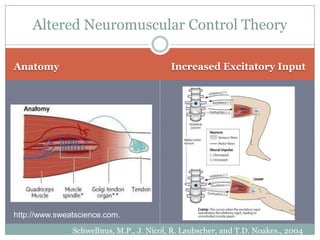

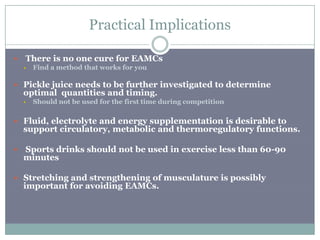

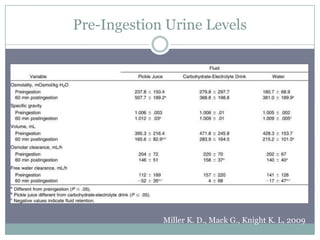

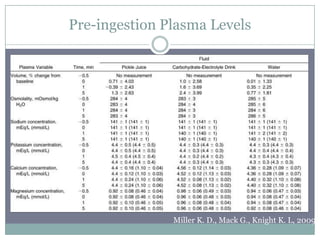

The document discusses exercise-associated muscle cramps (EAMCs), their causes, and the effects of hydration and electrolyte levels on performance. It highlights different methods for preventing EAMCs, including hydration strategies, the controversial use of pickle juice, and the importance of stretching. Future research needs are identified, emphasizing the need for more controlled studies on EAMCs and effective treatments.