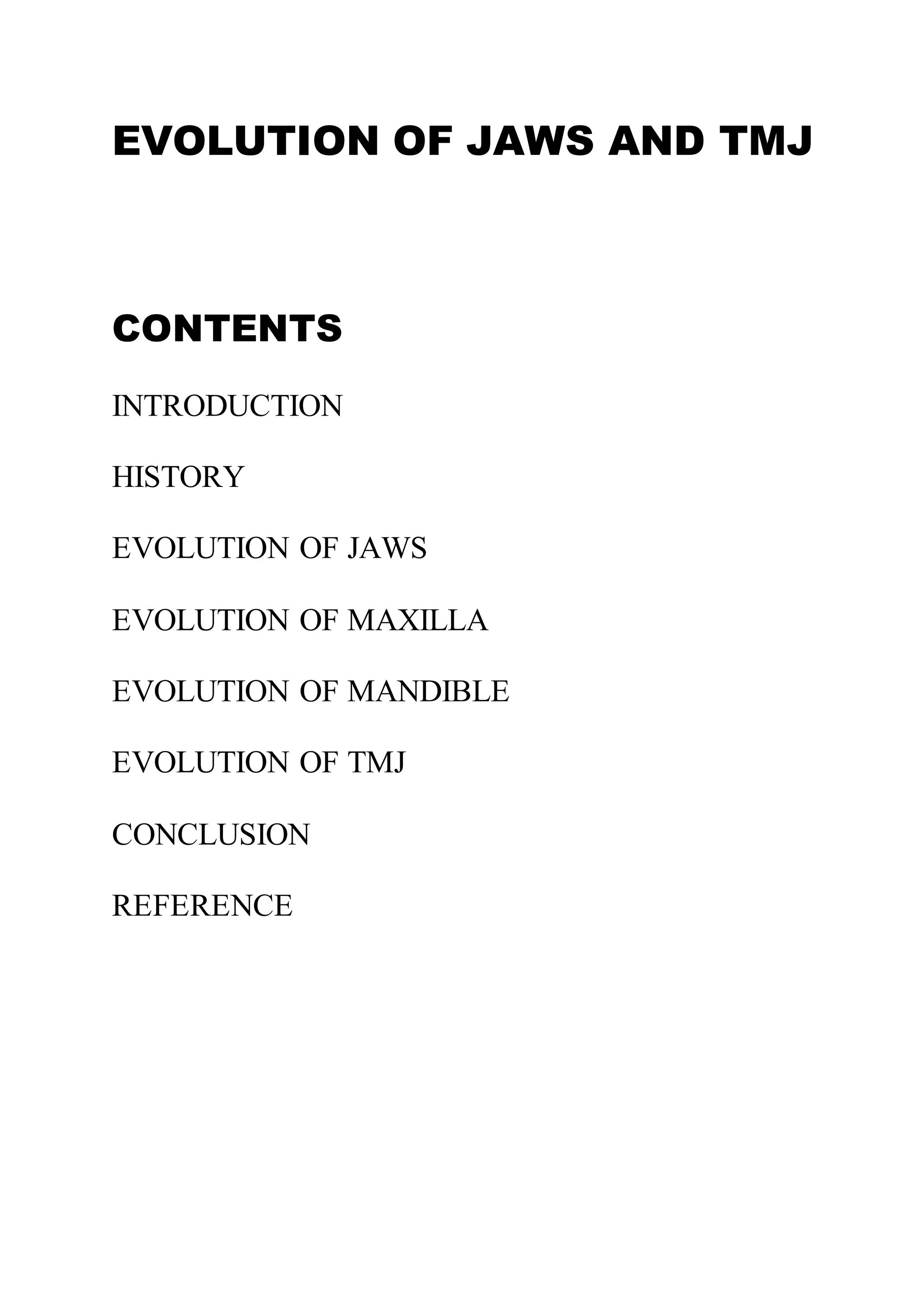

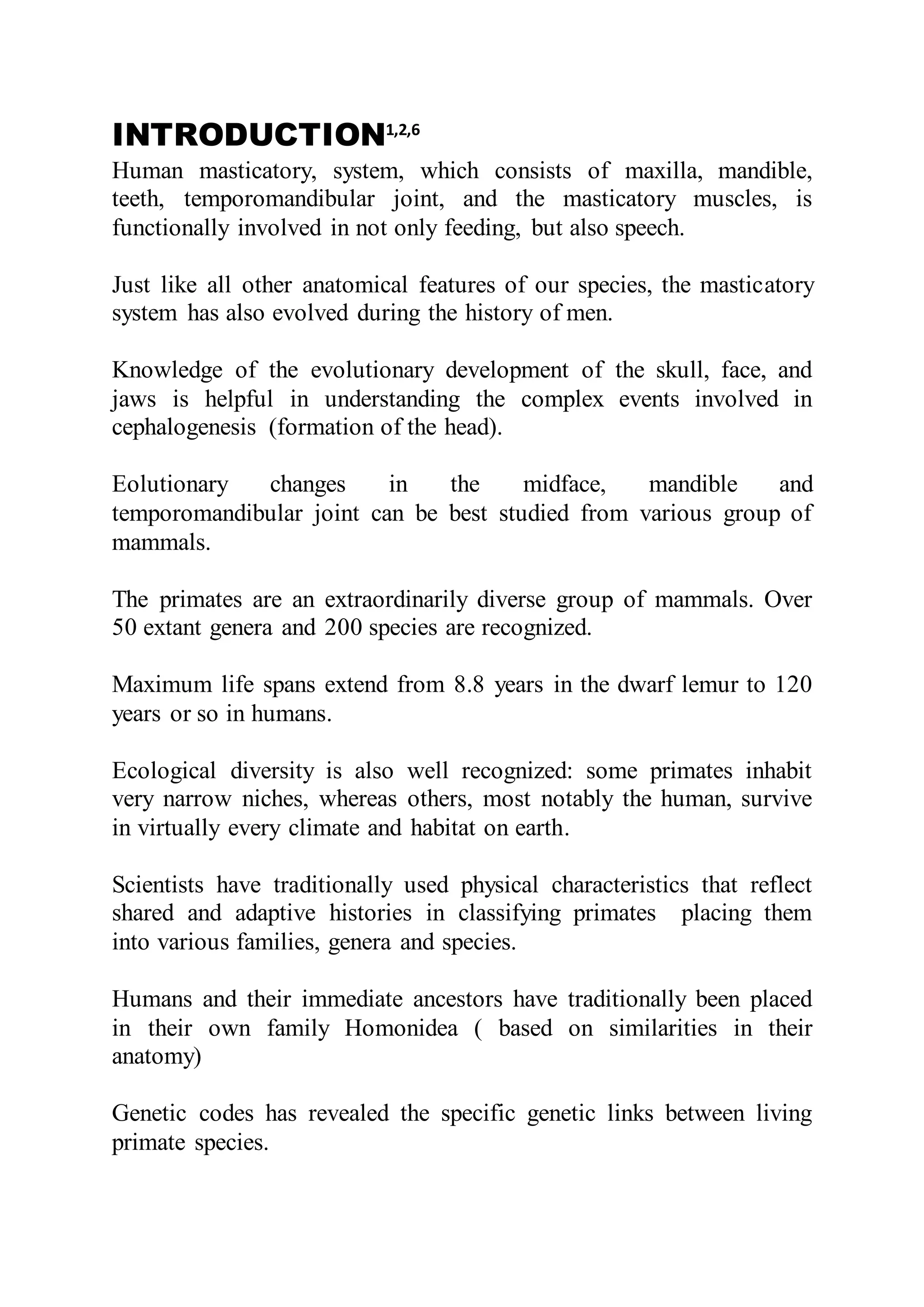

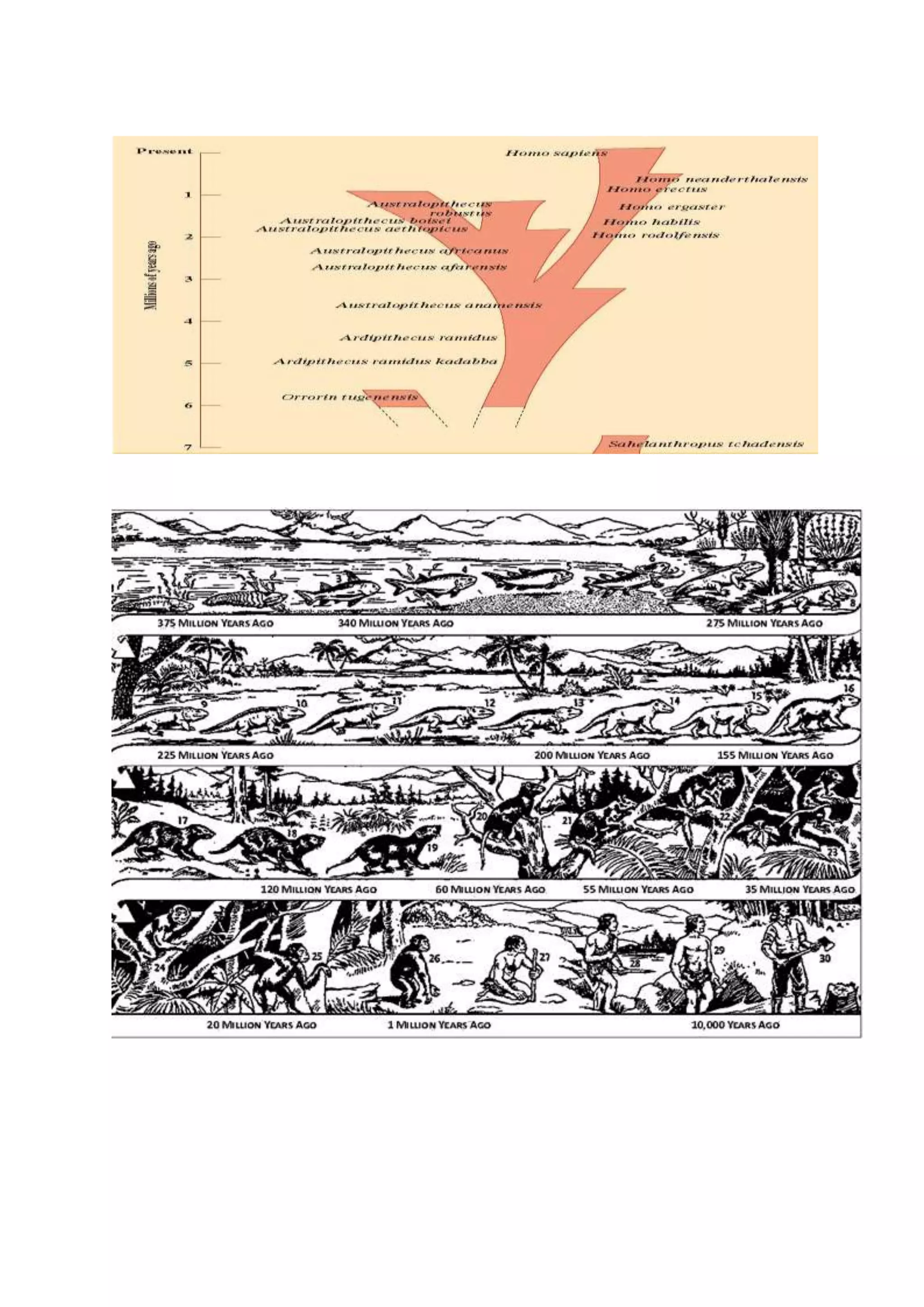

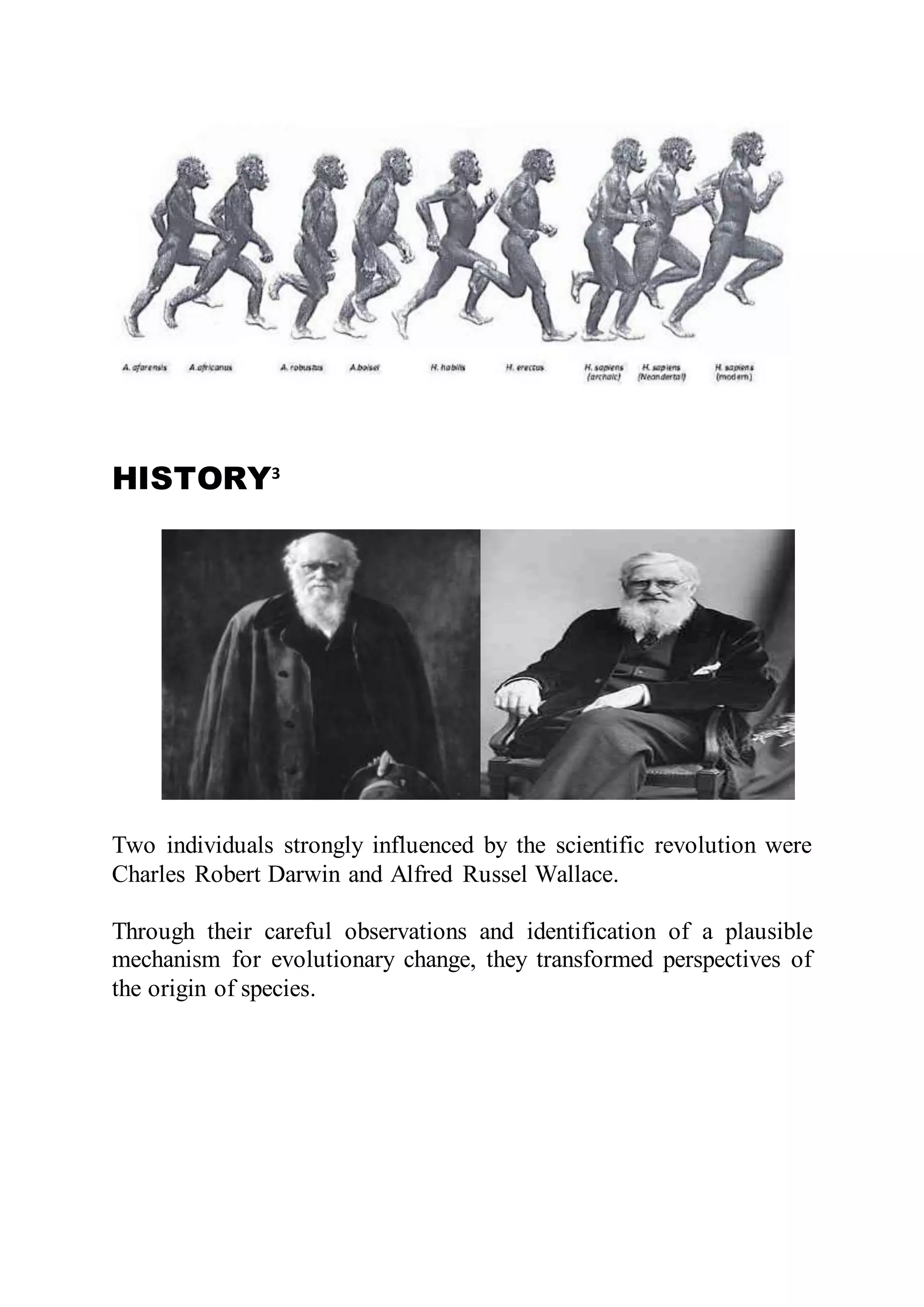

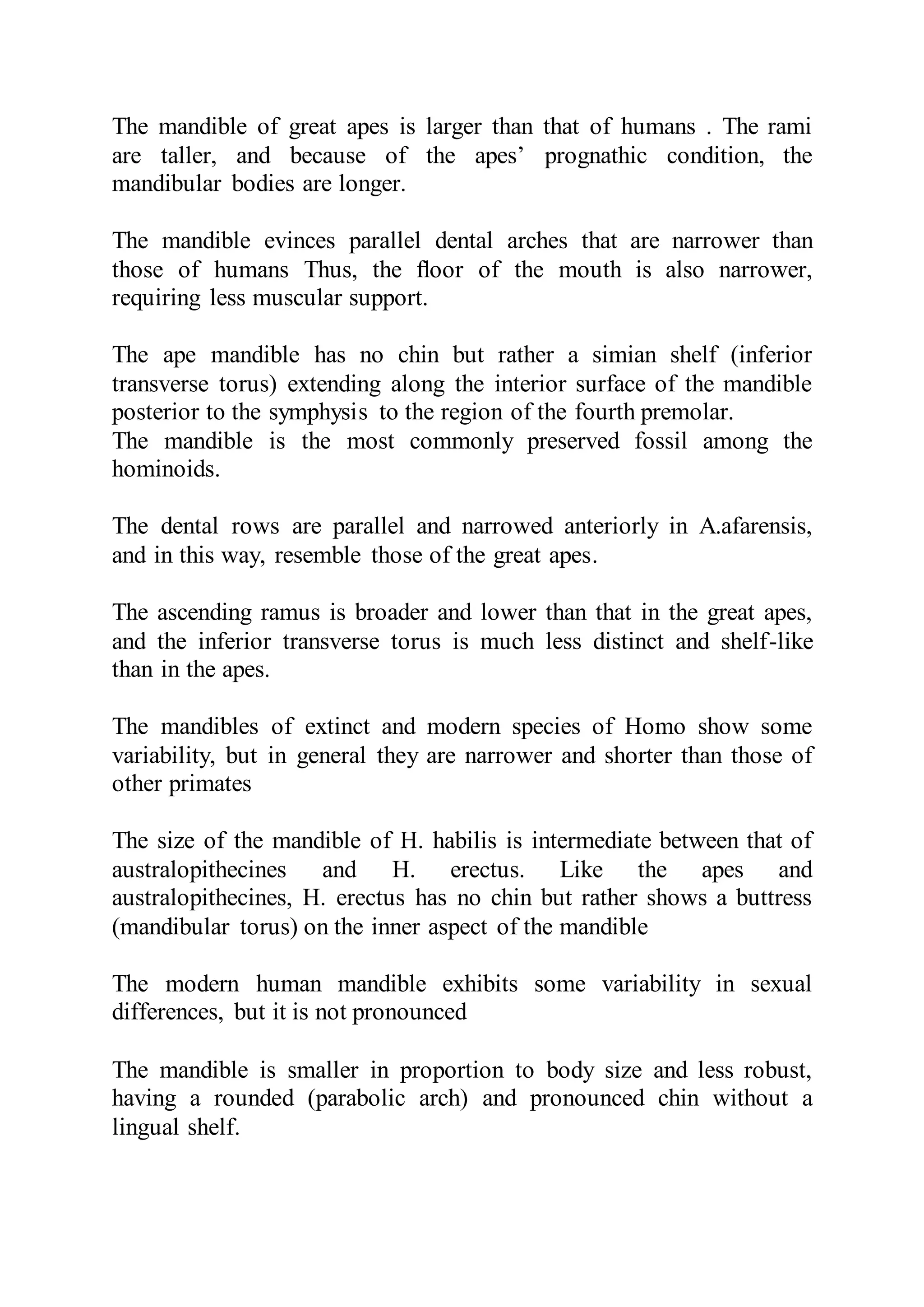

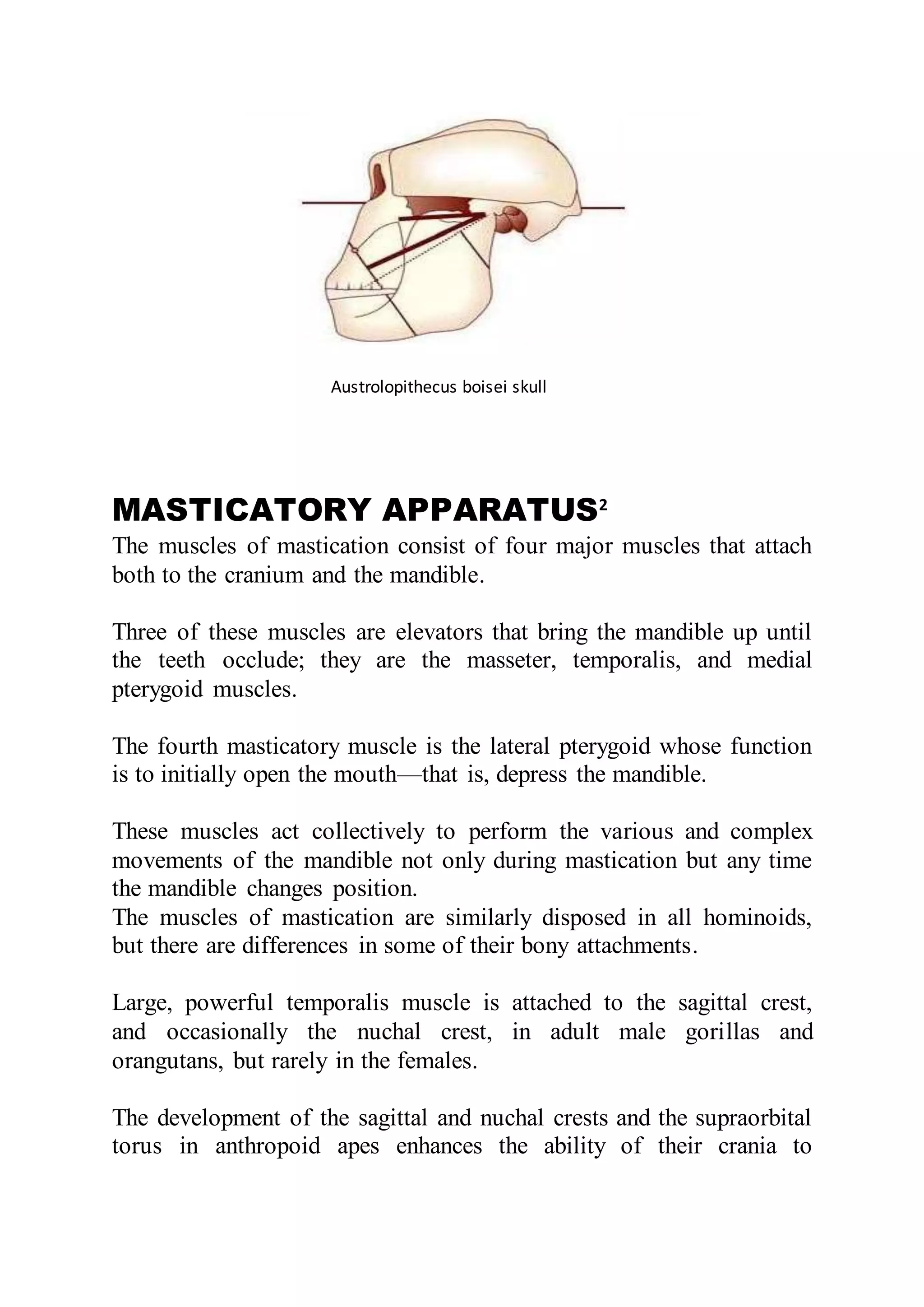

The document discusses the evolution of the human masticatory system, including jaws and temporomandibular joint (TMJ). It describes how Darwin and Wallace developed the theory of natural selection to explain evolution. The size of human jaws and maxilla have decreased compared to great apes due to dietary changes. The protruding chin is an evolutionary feature that separates humans from ancestors. Early humans experienced a reduction in jaw size that has persisted in modern humans. Diet influences the size and shape of jaws, maxilla, and dental arches.