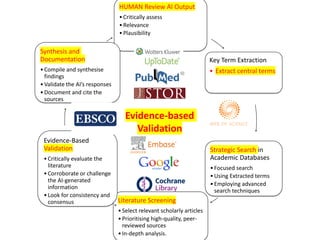

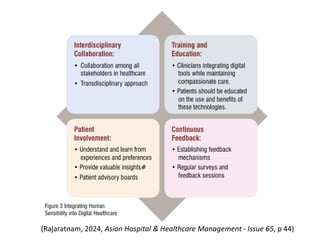

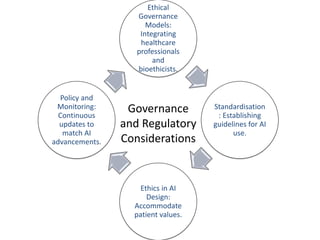

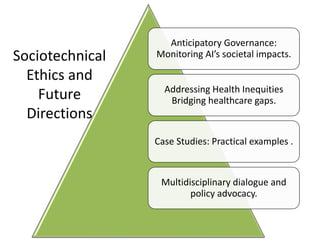

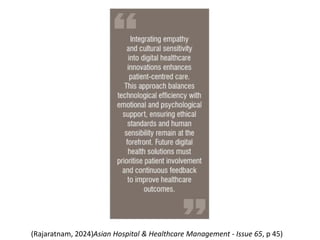

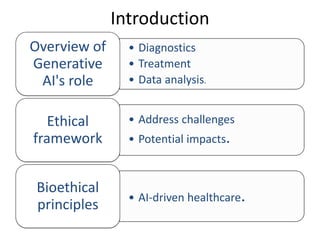

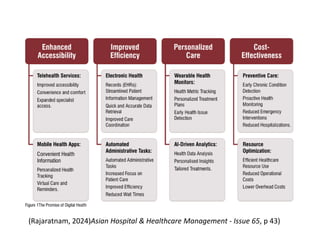

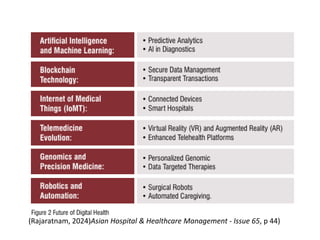

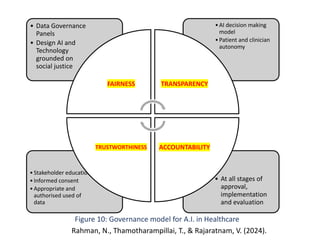

The document discusses the ethical implications of generative AI in healthcare, emphasizing core principles such as beneficence, nonmaleficence, autonomy, and justice. It highlights the challenges posed by AI in shared decision-making between patients and physicians and the need for robust governance and ethical frameworks to ensure equitable and responsible AI use. Further, it addresses the complexities of integrating AI in clinical settings, advocating for continuous dialogue among stakeholders to navigate ethical dilemmas effectively.

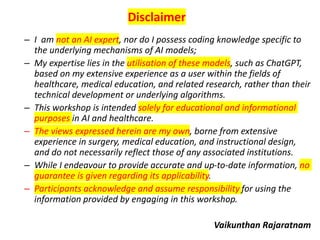

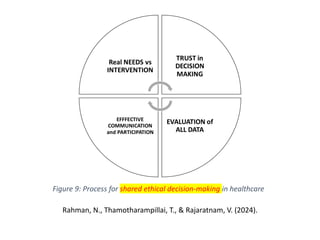

![Short description of

the components of

shared decision-

making

Expanded descriptions of the

components of what is required of

doctors in shared decision-making.

These can be perceived as minimum

standards

How AI can undermine the conditions for shared

decision-making

(a) Understanding

the patient’s

condition

Doctors must understand the

connection between patients’

conditions and the need for potential

interventions on a general, technical,

and normative level and translate them

into individual patients' particular

contexts.

If the clinical outcome of A.I. is beyond what doctors are

able to understand themselves, their clinical

competence is undermined, and by that, a crucial

presupposition for why the patients have reason to

trust them in the first place [38].

(b) Trust in evidence Doctors must base their decisions on

sources of evidence they trust to ensure

the information is relevant and

adequate.

If doctors suggest treatments on the basis of AI sources

to information they cannot fully account for, they force

patients to place blind trust in their recommendations.

This is just another version of paternalism.

(c) Due assessment

of benefits and risks

Doctors must understand all relevant

information of benefits and risks and

trade-offs between them.

If doctors cannot fully understand how and why A.I. has

reached an outcome, say, the classification of an x-ray,

uncertainty regarding assessments of risks, benefits and

trade-offs will follow. This, in turn, undermines

’patients’ reasons to have confidence in their judgments

as their role as the expert in the relation.

(d) Accommodating

” ’patient’s

understanding,

communication,

and deliberation

Doctors must convey an assessment of risks

and benefits to patients in a clear and

accessible manner, ensure they have

understood the information, and invite them to

share their thoughts and deliberate together

on the matter.

If AI systems make it hard for doctors to understand

how and why they reach their outcomes, they cannot

facilitate patients' understanding. Instead, they will

have to paternalistically require that the patient accept

that the A.I. ‘knows best’.

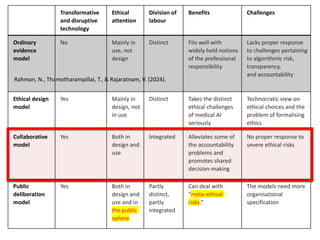

Rahman, N., Thamotharampillai, T., &

Rajaratnam, V. (2024).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ethicsofgenerativeaiinhealthcare-241030034815-3490b1e1/85/Ethics_of_Generative_AI_in_Healthcare-pdf-12-320.jpg)