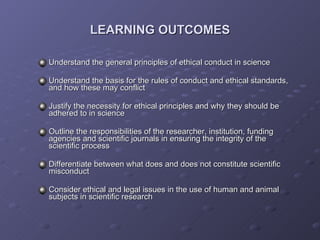

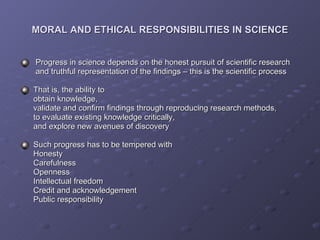

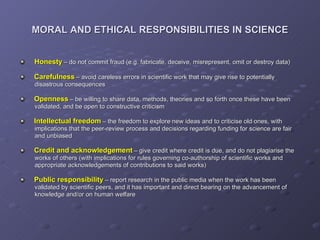

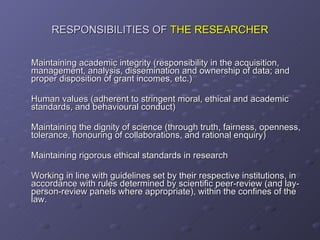

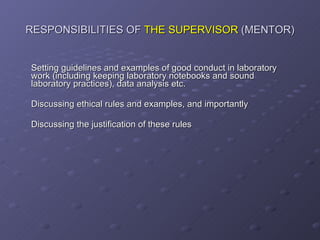

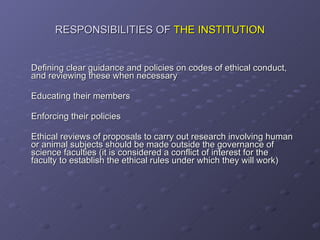

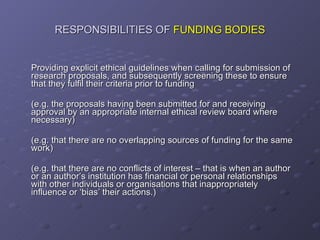

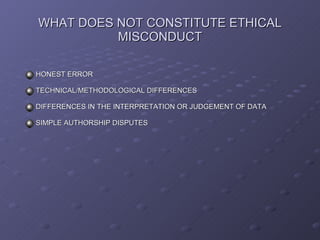

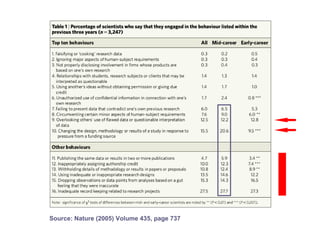

This document outlines the ethical principles and responsibilities in scientific conduct. It discusses the need for ethical standards to ensure science benefits society and avoids harm. Some key responsibilities are outlined, including for researchers to maintain integrity, for institutions to define policies, and for funding bodies and journals to enforce guidelines. The goals are to foster trust in science and accountability among all involved parties.