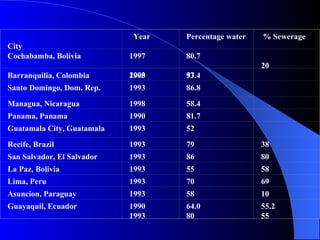

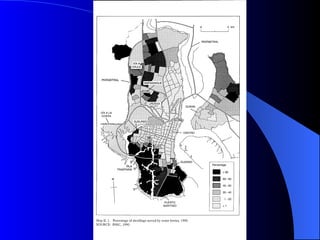

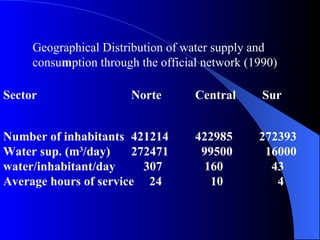

The document discusses circulations and metabolisms in hybrid natures and cyborg cities. It covers socio-natural metabolisms, the invention of circulation, hybrid natures in cities, and flows of power using the case study of Guayaquil, Ecuador's waters. Historical materialist perspectives view metabolism as a central metaphor involving the transformation and maintenance of the relationship between humans and nature through labor.

![Historical-Materialist Perspectives 1. Socio-Natural Metabolisms The materialist foundation “ The first premise of all human history is, of course, the existence of living human individuals. Thus the first fact to be established is the physical organisation of these individuals and their consequent relationship to the rest of nature… The writing of history must always set out from these natural bases and their modification in the course of history through the action of men … [M]en must be in a position to live in order to be able to ‘make history’… The first historical act is thus the production of the means to satisfy these needs, the production of material life itself.”](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/urbanmetabolisms-100706200011-phpapp02/85/Course-29-6-Erik-Swyngedouw-4-320.jpg)

![Labour as a ‘natural process’ “ Labour is, first of all, a process between man and nature, a process by which man, through his own actions, mediates, regulates, and controls the metabolism between himself and nature. He confronts the materials of nature as a force of nature. He sets in motion the natural forces which belong to his own body, his arms, legs, head, and hands, in order to appropriate the materials of nature in a form adapted to his own needs. Through this movement he acts upon external nature and changes it, and in this way he simultaneously changes his own nature …. [labouring] is an appropriation of what exists in nature for the requirements of man. It is the universal condition for the metabolic interaction between man and nature, the ever-lasting nature-imposed condition of human existence” (Marx 1867 (1971): 283 and 290).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/urbanmetabolisms-100706200011-phpapp02/85/Course-29-6-Erik-Swyngedouw-5-320.jpg)