This study developed and evaluated a common factors feedback (CFF) system aimed at improving the psychotherapy process for clients with depressive symptoms by providing ongoing feedback on outcome expectations, empathy, and therapeutic alliance. A randomized clinical trial involving 79 undergraduate participants showed that clients using the CFF system reported greater improvements in perceived empathy and therapeutic alliance than those receiving treatment as usual. The findings suggest that the CFF system is well received and has the potential to enhance therapeutic processes in treatment for depression.

![(e.g.,

humanistic and psychodynamic therapies) do not target

symptoms

per se and thus may be more compatible with a process

feedback

system than an outcome/symptom-based feedback system.

Third,

whereas therapists may view outcome feedback as evaluative

and

threatening (Boswell, Krauss, Miller, & Lambert, 2015),

therapists

This article was published Online First January 23, 2017.

Andrew S. McClintock, Matthew R. Perlman, Shannon M.

McCarrick,

Timothy Anderson, and Lina Himawan, Department of

Psychology, Ohio

University.

The ideas and data reported in this article have not been

previously

disseminated.

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to

Andrew

S. McClintock, 264 Porter Hall, Athens, OH 45701. E-mail:

[email protected]

ohio.edu

T

hi

s

do](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/enhancingpsychotherapyprocesswithcommonfactorsfeedback-230108091546-8446de24/85/Enhancing-Psychotherapy-Process-With-Common-Factors-Feedback-docx-4-320.jpg)

![oa

dl

y.

Journal of Counseling Psychology © 2017 American

Psychological Association

2017, Vol. 64, No. 3, 247–260 0022-0167/17/$12.00

http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/cou0000188

247

mailto:[email protected]

mailto:[email protected]

http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/cou0000188

may be more receptive to feedback about what is transpiring in

therapy. Thus, process feedback has the potential to be more

widely implemented. Fourth, a process feedback system could

yield information that is actionable and immediately useful. For

example, disagreement about treatment tasks could be readily

addressed by exploring discrepancies between the implemented

techniques and the client’s perceptions about which techniques

should be implemented.

An exemplary system that integrates process and outcome feed-

back is the Partners for Change Outcome Management System

(PCOMS; Miller et al., 2005; Duncan, 2012). PCOMS monitors

the therapeutic alliance (i.e., agreement on therapeutic goals

and

tasks in the context of a positive affective bond; Bordin, 1979)

at

every session, enabling therapists to identify and repair alliance

ruptures on an ongoing basis. Although the effectiveness of

PCOMS is well documented (e.g., Duncan, 2012), it is unclear](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/enhancingpsychotherapyprocesswithcommonfactorsfeedback-230108091546-8446de24/85/Enhancing-Psychotherapy-Process-With-Common-Factors-Feedback-docx-9-320.jpg)

![To account for the different shapes that the growth curve might

take, four different unconditional growth curves were fitted to

the

data, and the best model was obtained by comparing the

informa-

tion criteria (i.e., Akaike Information Criteria [AIC] and

Bayesian

Information Criteria [BIC]). The four unconditional growth

curves

were as follows: (a) a linear unconditional growth curve (i.e., a

model with only a linear term of session number included as the

Level 1 predictor) to assess the possibility that scores decrease

or

increase at a constant rate over time; (b) a log unconditional

growth curve (i.e., a model with only a log of session number

included as the Level 1 predictor) to assess the possibility that

scores decrease or increase at a faster rate during the early ses-

sions, then decrease or increase at a slower rate during the later

sessions; (c) a quadratic unconditional growth curve (i.e., a

model

with linear and quadratic terms of session number as the Level 1

predictors) to assess the possibility that scores first decrease

over

time then increase or first increase then decrease; and (5) a

cubic

unconditional quadratic growth curve (i.e., a model with linear,

quadratic, and cubic terms of session number as the Level 1

predictors) to assess the possibility that scores decrease first

over

Figure 2. Example of feedback graph. See the online article for

the color version of this figure.

T

hi](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/enhancingpsychotherapyprocesswithcommonfactorsfeedback-230108091546-8446de24/85/Enhancing-Psychotherapy-Process-With-Common-Factors-Feedback-docx-48-320.jpg)

![r0ij

� r1ij(Session)tij � etij]

In the previous model, (Measure)tij is the process/outcome

measure

(i.e., BDI-II, SOS-10, WAI-SR, BLRI-E, or OEQ) at time t for

client

i seeing therapist j; because Session was centered at the first

session

(i.e., immediately before first session for BDI-II, SOS-10 and

OEQ

and immediately after first session for BLRI-E and WAI-SR),

�000 is

the average of the scores at the first session; and �100 is the

rate of

change of the scores over one unit of time (i.e., session). A

significant

�000 means that the average of the scores at the first session is

significantly different than zero. A significant �100 means that

the

scores change significantly over time (i.e., the rate of change of

the scores is significantly different than zero). The parameters

inside

the brackets are the random effects: etij is the session

variability within

a client; r0ij and r1ij are client variability within a therapist

around �000

and �100, respectively; and u00j and u10j are therapist

variability

around �000 and �100, respectively. In the beginning of the

model

fitting, �000 and �100 were treated as random effects at both

Levels 2

and 3. However, when there was an indication that the model

was](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/enhancingpsychotherapyprocesswithcommonfactorsfeedback-230108091546-8446de24/85/Enhancing-Psychotherapy-Process-With-Common-Factors-Feedback-docx-54-320.jpg)

![overspecified, these random effects were dropped one by one

starting

from the highest level, until the model fit properly.

Also for illustration purposes, the linear model fitted with treat-

ment condition (TC) as a Level 2 predictor is provided here:

Level 1:

(Measure)tij � �0ij � �1ij(Session)tij � etij

Level 2:

�0ij � �00j � �01j(TC)ij � r0ij

�1ij � �10j � �11j(TC)ij � r1ij

Level 3:

�00j � �000 � u00j

�01j � �010

�10j � �100 � u10j

�11j � �110

The complete model:

(Measure)tij � �000 � �010(TC)ij � �100(Session)tij

� �110(TC)ij(Session)tij � [u00j � u10j(Session)tij

� r0ij � r1ij(Session)tij � etij]

In the previous model, (Measure)tij is the process/outcome

measure

at time t for client i seeing therapist j; because Session was

centered

at the first session and Treatment Condition was centered at](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/enhancingpsychotherapyprocesswithcommonfactorsfeedback-230108091546-8446de24/85/Enhancing-Psychotherapy-Process-With-Common-Factors-Feedback-docx-55-320.jpg)

![(BDI-II)tij � �000 � �100(Session)tij � [u00j �

u10j(Session)tij � r0ij

� r1ij(Session)tij � etij]

(2) SOS-10

(SOS-10)tij � �000 � �100(Session)tij � [u10j(Session)tij �

r0ij

� r1ij(Session)tij � etij]

(3) WAI-SR

(WAI-SR)tij � �000 � �100(LogSession)tij

� [r0ij � r1ij(LogSession)tij � etij]

(4) BLRI-E

(BLRI-E)tij � �000 � �100(LogSession)tij �

[u10j(LogSession)tij

� r0ij � r1ij(LogSession)tij � etij]

(5) OEQ

(OEQ)tij � �000 � �100(Session)tij � [r0ij � r1ij(Session)tij

� etij]

Results indicated that the average of the scores at the first

session (i.e.,

�000) and the rate of change over time/session (i.e., �100)

were](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/enhancingpsychotherapyprocesswithcommonfactorsfeedback-230108091546-8446de24/85/Enhancing-Psychotherapy-Process-With-Common-Factors-Feedback-docx-64-320.jpg)

![significantly different than zero. As expected, BDI-II scores

decreased

over time, while SOS-10, WAI-SR, BLRI-E, and OEQ scores in-

creased over time. Over one unit of time/session, BDI-II scores

decreased by 2.74 points, SOS-10 scores increased by 2.42

points,

WAI-SR scores increased by 5.75 points, BLRI-E scores

increased by

0.32 points, and OEQ scores increased by 2.21 points. A

summary of

the unconditional growth curve results is presented in Table 2.

In the next set of analyses, treatment condition was entered as a

Level 2 predictor. The final conditional growth curves were:

(1) BDI-II

(BDI-II)tij � �000 � �010(TC)ij � �100(Session)tij

� �110(TC)ij(Session)tij � [u00j � u10j(Session)tij

� r0ij � r1ij(Session)tij � etij]

(2) SOS-10

(SOS-10)tij � �000 � �010(TC)ij � �100(Session)tij

� �110(TC)ij(Session)tij � [u10j(Session)tij � r0ij

� r1ij(Session)tij � etij]

(3) WAI-SR

(WAI-SR)tij � �000 � �010(TC)ij � �100(LogSession)tij

� �110(TC)ij(LogSession)tij � [u10j(LogSession)tij](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/enhancingpsychotherapyprocesswithcommonfactorsfeedback-230108091546-8446de24/85/Enhancing-Psychotherapy-Process-With-Common-Factors-Feedback-docx-65-320.jpg)

![� r0ij � r1ij(LogSession)tij � etij]

(4) BLRI-E

(BLRI-E)tij � �000 � �010(TC)ij � �100(LogSession)tij

� �110(TC)ij(LogSession)tij � [u10j(LogSession)tij

� r0ij � r1ij(LogSession)tij � etij]

(5) OEQ

(OEQ)tij � �000 � �010(TC)ij � �100(Session)tij

� �110(TC)ij(Session)tij � [r0ij � r1ij(Session)tij � etij]

Results indicated that for each process/outcome measure, the

average of TAU scores at the first session (i.e., �000) was

signif-

icantly different than zero. For each process/outcome measure,

the

effect of the TAU � CFF condition on �000 (i.e., �010) was

not

significant. This implies that, as would be expected given

random-

Table 1

Means (SDs) and Correlations for Study Measures at First

Session (N � 79)

Study measures M (SD) BDI-II SOS-10 WAI-SR BLRI-E OEQ

BDI-II 23.68 (8.21) �.65��� �.17 .22 .03

SOS-10 31.26 (8.32) .19 �.02 .08

WAI-SR 43.60 (7.83) .63��� .48���](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/enhancingpsychotherapyprocesswithcommonfactorsfeedback-230108091546-8446de24/85/Enhancing-Psychotherapy-Process-With-Common-Factors-Feedback-docx-66-320.jpg)

![common factor in brief treatments for depression.

Psychotherapy Re-

search, 17, 137–147.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10503300600919380

Received August 20, 2016

Revision received November 7, 2016

Accepted November 7, 2016 �

Members of Underrepresented Groups:

Reviewers for Journal Manuscripts Wanted

If you are interested in reviewing manuscripts for APA journals,

the APA Publications and

Communications Board would like to invite your participation.

Manuscript reviewers are vital to the

publications process. As a reviewer, you would gain valuable

experience in publishing. The P&C

Board is particularly interested in encouraging members of

underrepresented groups to participate

more in this process.

If you are interested in reviewing manuscripts, please write

APA Journals at [email protected]

Please note the following important points:

• To be selected as a reviewer, you must have published articles

in peer-reviewed journals. The

experience of publishing provides a reviewer with the basis for

preparing a thorough, objective

review.

• To be selected, it is critical to be a regular reader of the five

to six empirical journals that are most

central to the area or journal for which you would like to](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/enhancingpsychotherapyprocesswithcommonfactorsfeedback-230108091546-8446de24/85/Enhancing-Psychotherapy-Process-With-Common-Factors-Feedback-docx-167-320.jpg)

![459891TMTXXX10.1177/153

4765612459891TraumatologyNelson

1Florida State University, Tallahassee, FL, USA

Corresponding Author:

Rebekah J. Nelson, Florida State University, 296 Champions

Way,

University Center, Building C, Tallahassee, FL 32306, USA.

Email: [email protected]

Is Virtual Reality Exposure Therapy

Effective for Service Members and

Veterans Experiencing Combat-

Related PTSD?

Rebekah J. Nelson1

Abstract

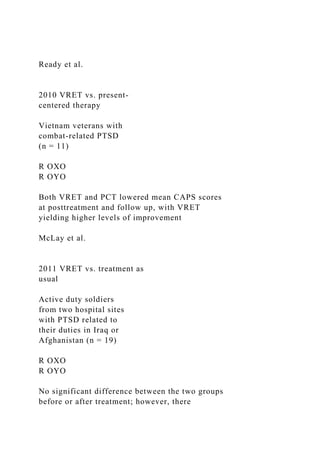

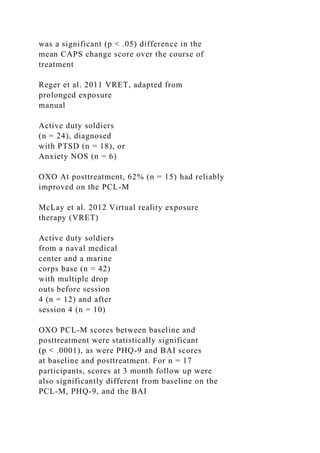

Purpose: Exposure therapy has been identified as an effective

treatment for anxiety disorders, including posttraumatic stress

disorder (PTSD). The use of virtual reality exposure therapy

(VRET) in the past decade has increased due to improvements

in

virtual reality technology. VRET has been used to treat active

duty service members and veterans experiencing posttraumatic

stress symptoms by exposing them to a virtual environment

patterned after the real-world environment in which the trauma

occurred. This article is a systematic review of the effectiveness

of using VRET with these two populations. Method: A

search of 14 databases yielded 6 studies with experimental or

quasi-experimental designs where VRET was used with active

duty service members or veterans diagnosed with combat-

related PTSD. Results: Studies show positive results for the

use of VRET in treating combat-related PTSD, though more](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/enhancingpsychotherapyprocesswithcommonfactorsfeedback-230108091546-8446de24/85/Enhancing-Psychotherapy-Process-With-Common-Factors-Feedback-docx-175-320.jpg)

![Bridging virtual and real worlds in the treatment of posttrau-

matic stress disorders. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social

Networking, 13(1), 55-65.

Rizzo, A., Reger, G., Gahm, G., Difede, J., & Rothbaum, B. O.

(2009). Virtual reality exposure therapy for combat related

PTSD. Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, 6, 375-399.

Rothbaum, B. O. (2006). Virtual Vietnam: Virtual reality

exposure

therapy. In M. Roy (Ed.), Novel approaches to the diagnosis

and treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder (pp. 205-218).

Amsterdam, The Netherlands: IOS Press.

Rothbaum, B. O., Hodges, L. F., Ready, D., Graap, K., &

Alarcon, R. D.

(2001). Virtual reality exposure therapy for Vietnam veterans

with posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychia-

try, 62, 617-622.

Stetz, M. C., Long, C. P., Wiederhold, B. K., & Turner, D. D.

(2008). Combat scenarios and relaxation training to harden

medics against stress. Journal of CyberTherapy & Rehabilita-

tion, 1, 239-246.

Virtual Iraq Afghanistan Media Story CBC [video file].

Retrieved

from http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ltl9zbDRZWY&

feature=autoplay&list=UUQrbzaW3x9wWoZPl4-l4GSA

&playnext=1

Wood, D. P., Murphy, J. A., Center, K. B., Russ, C., McLay, R.

N.,

Reeves, D., . . . Wiederhold, B. K. (2008). Combat related post-

traumatic stress disorder: A multiple case report using virtual

reality graded exposure therapy with physiological monitoring.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/enhancingpsychotherapyprocesswithcommonfactorsfeedback-230108091546-8446de24/85/Enhancing-Psychotherapy-Process-With-Common-Factors-Feedback-docx-229-320.jpg)