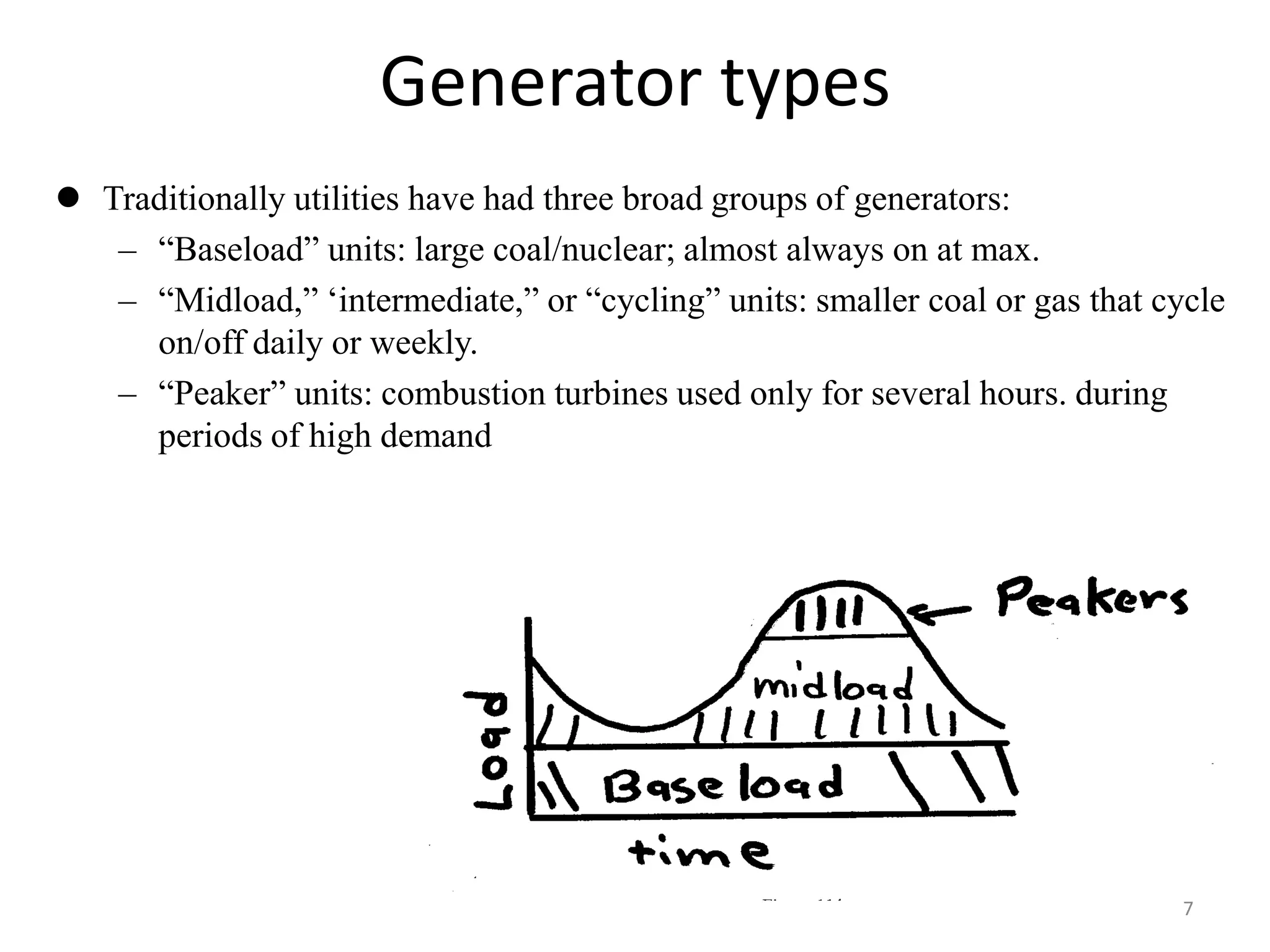

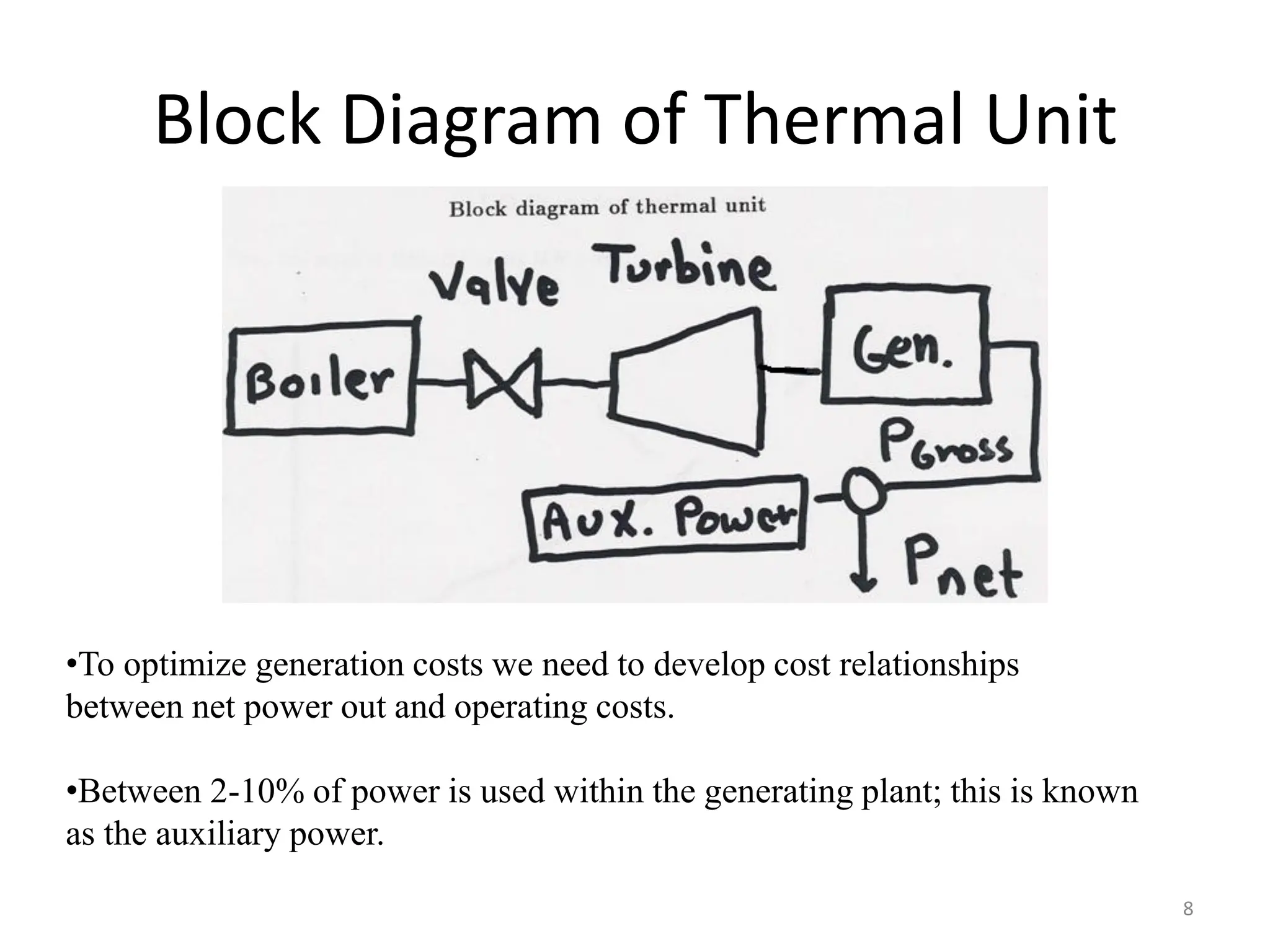

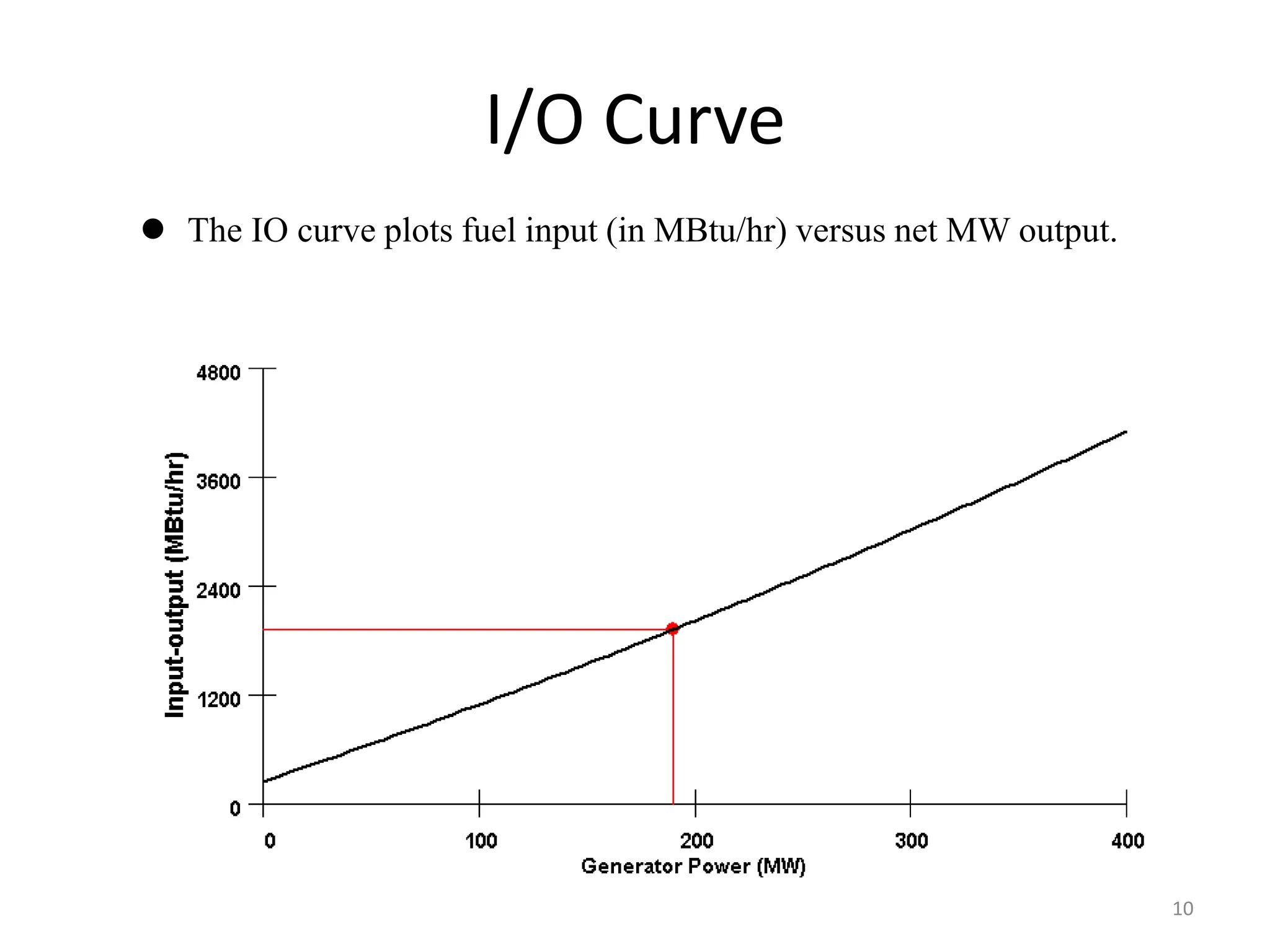

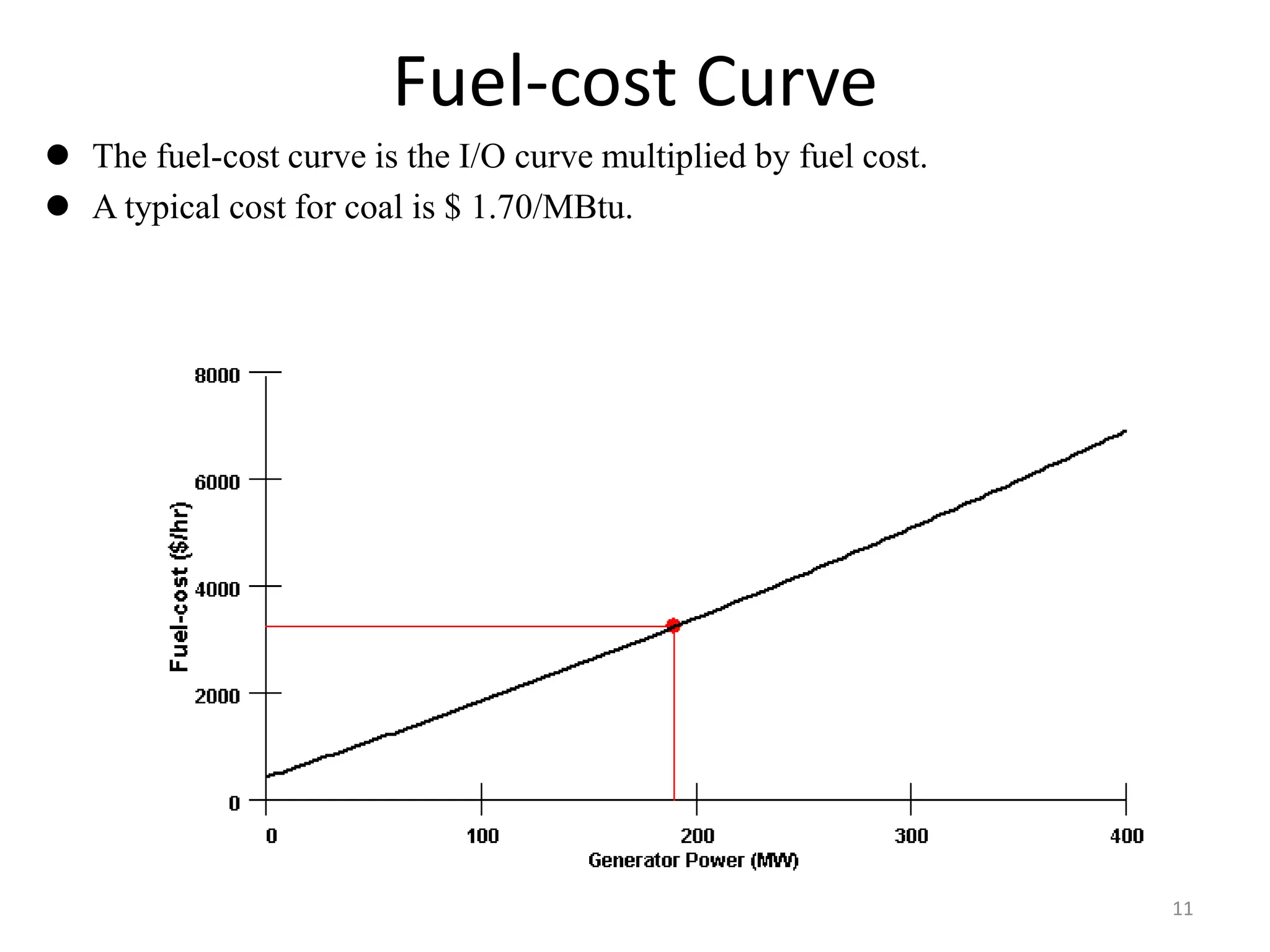

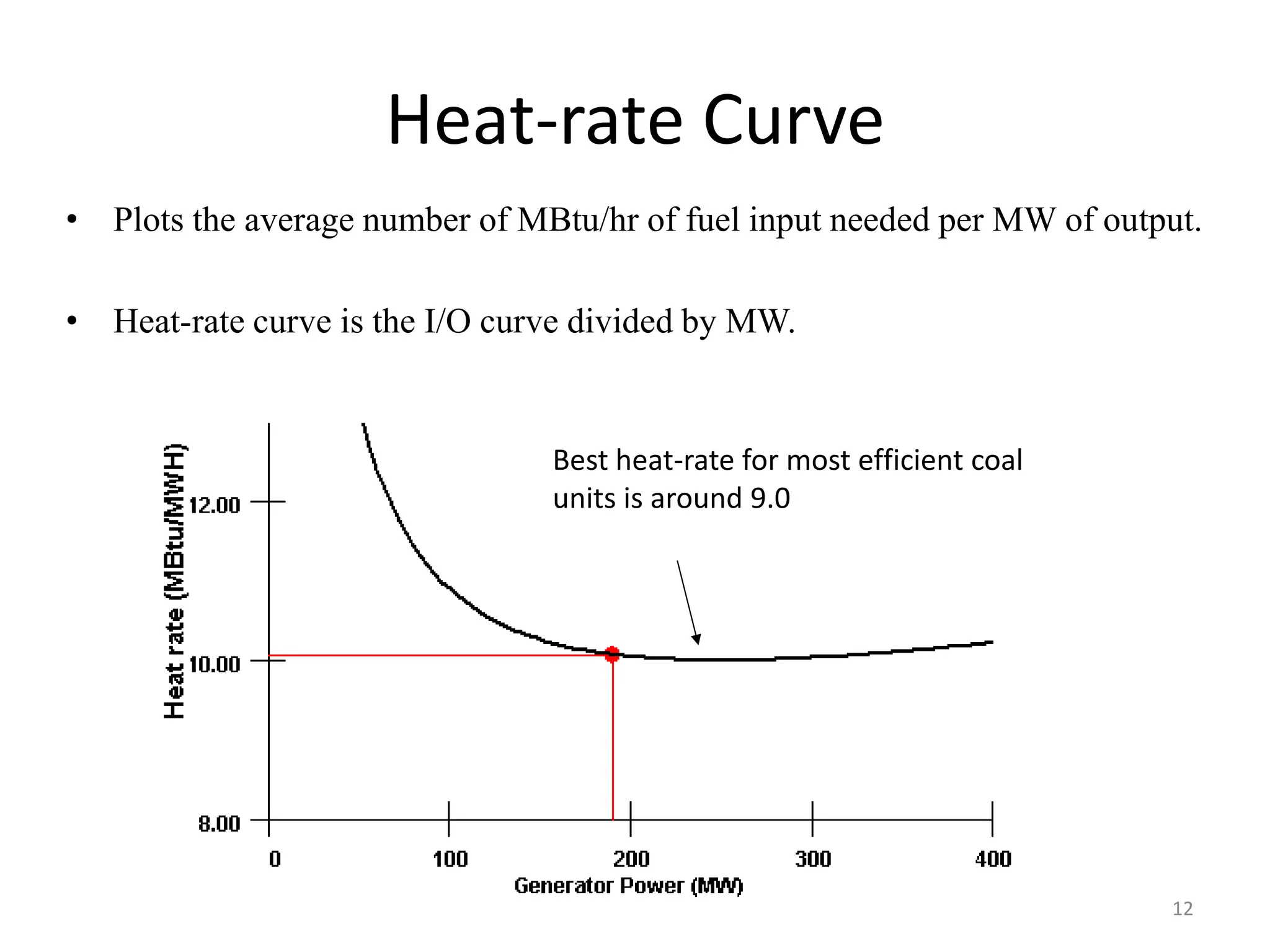

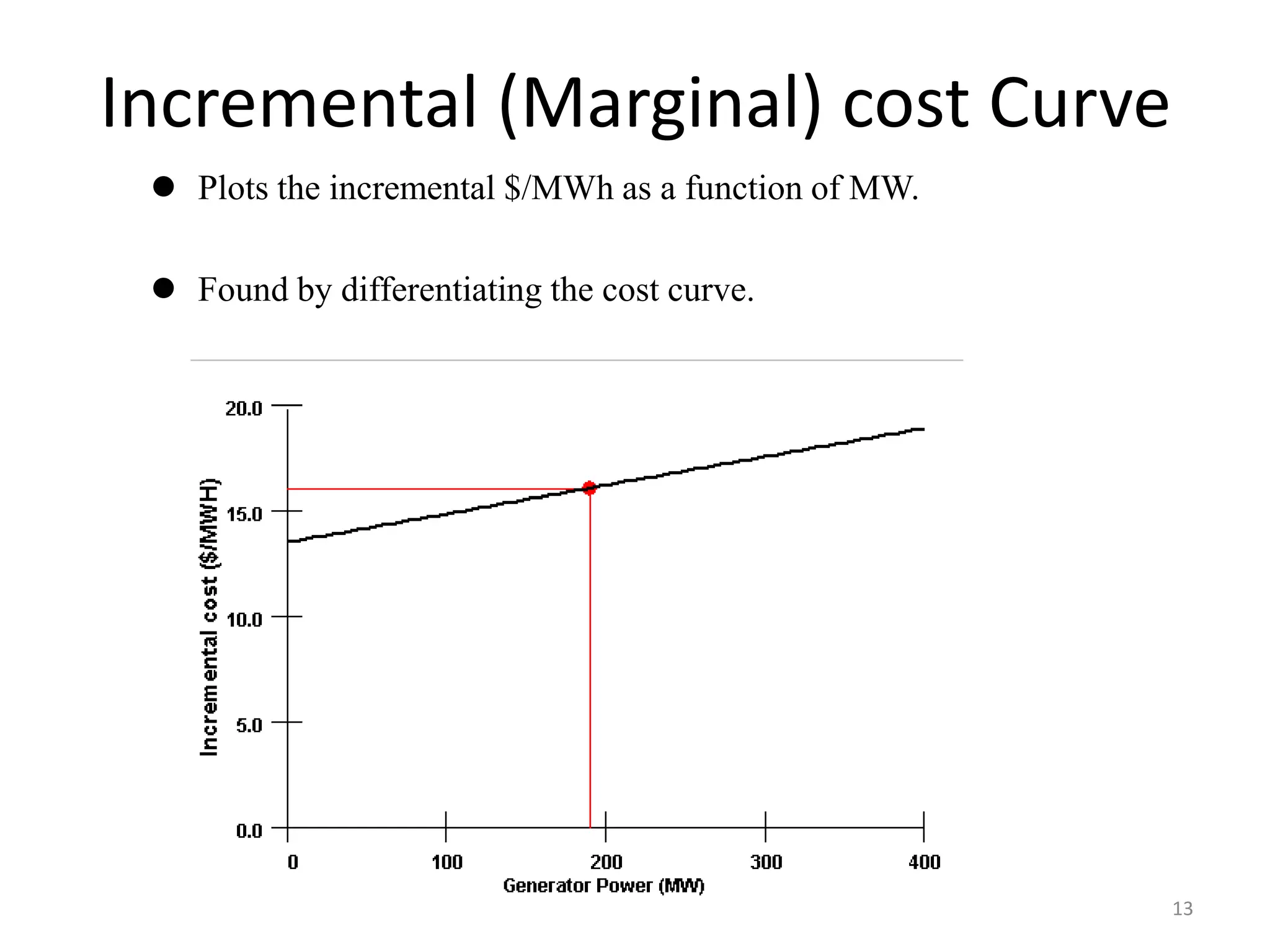

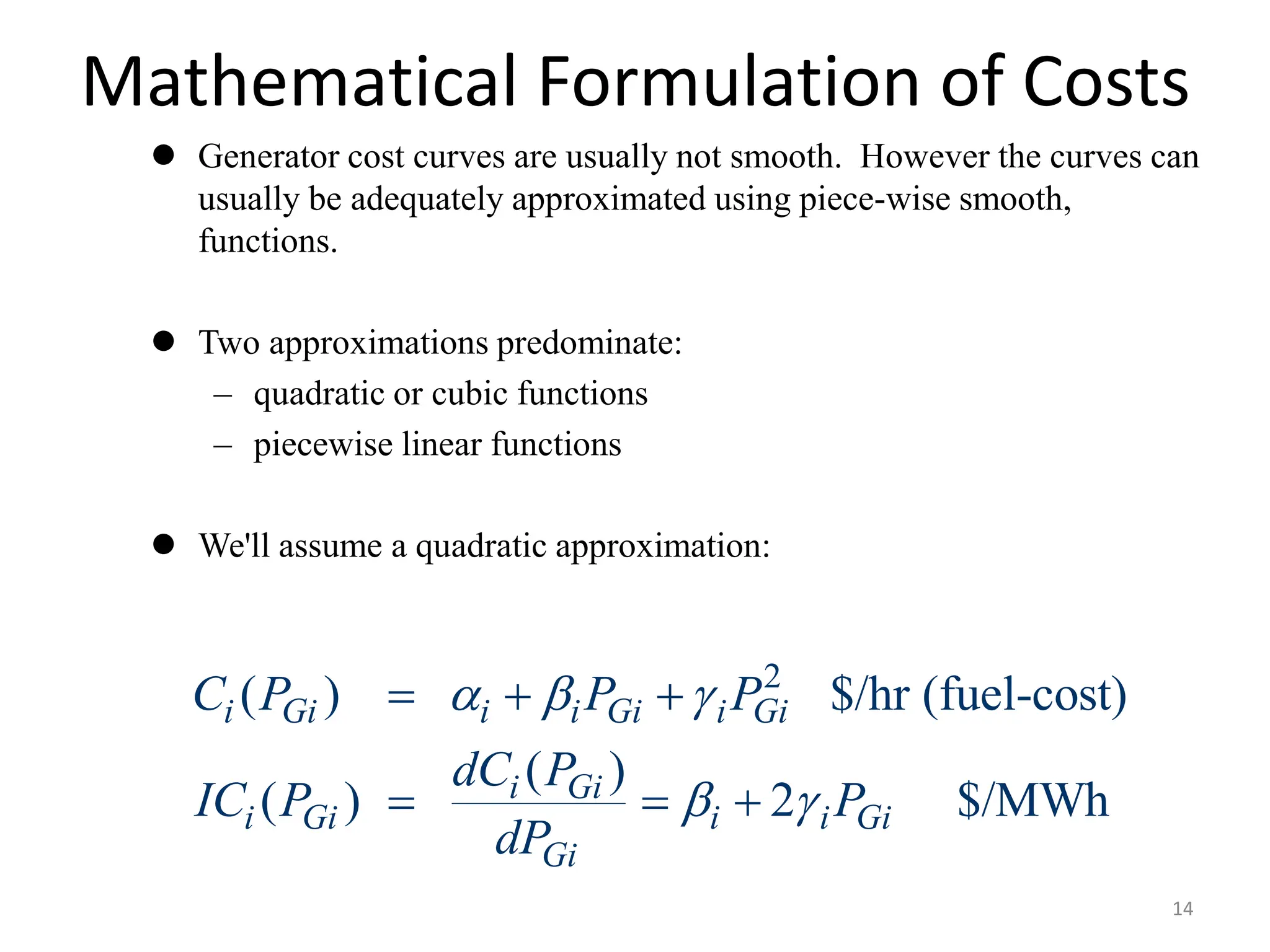

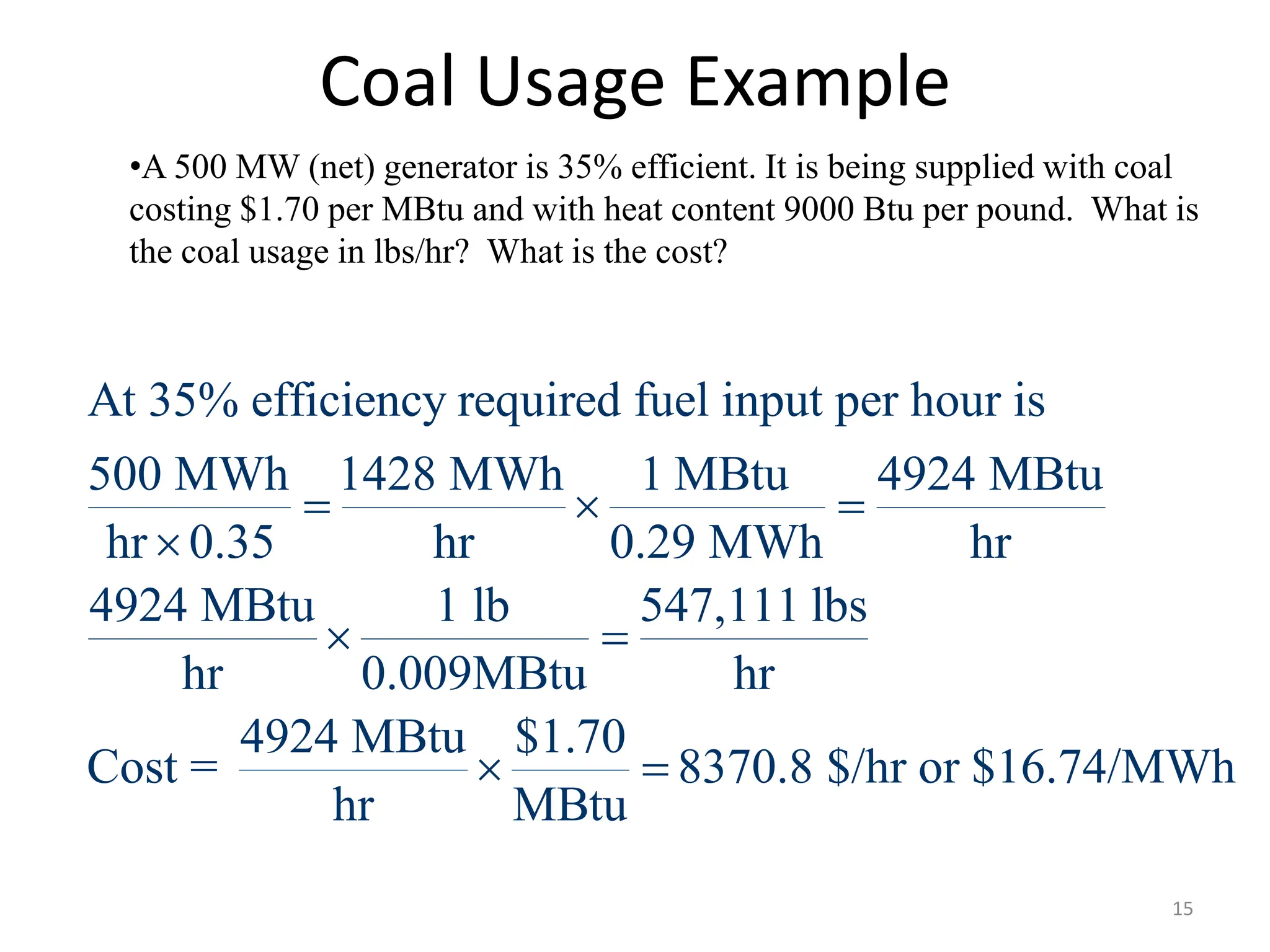

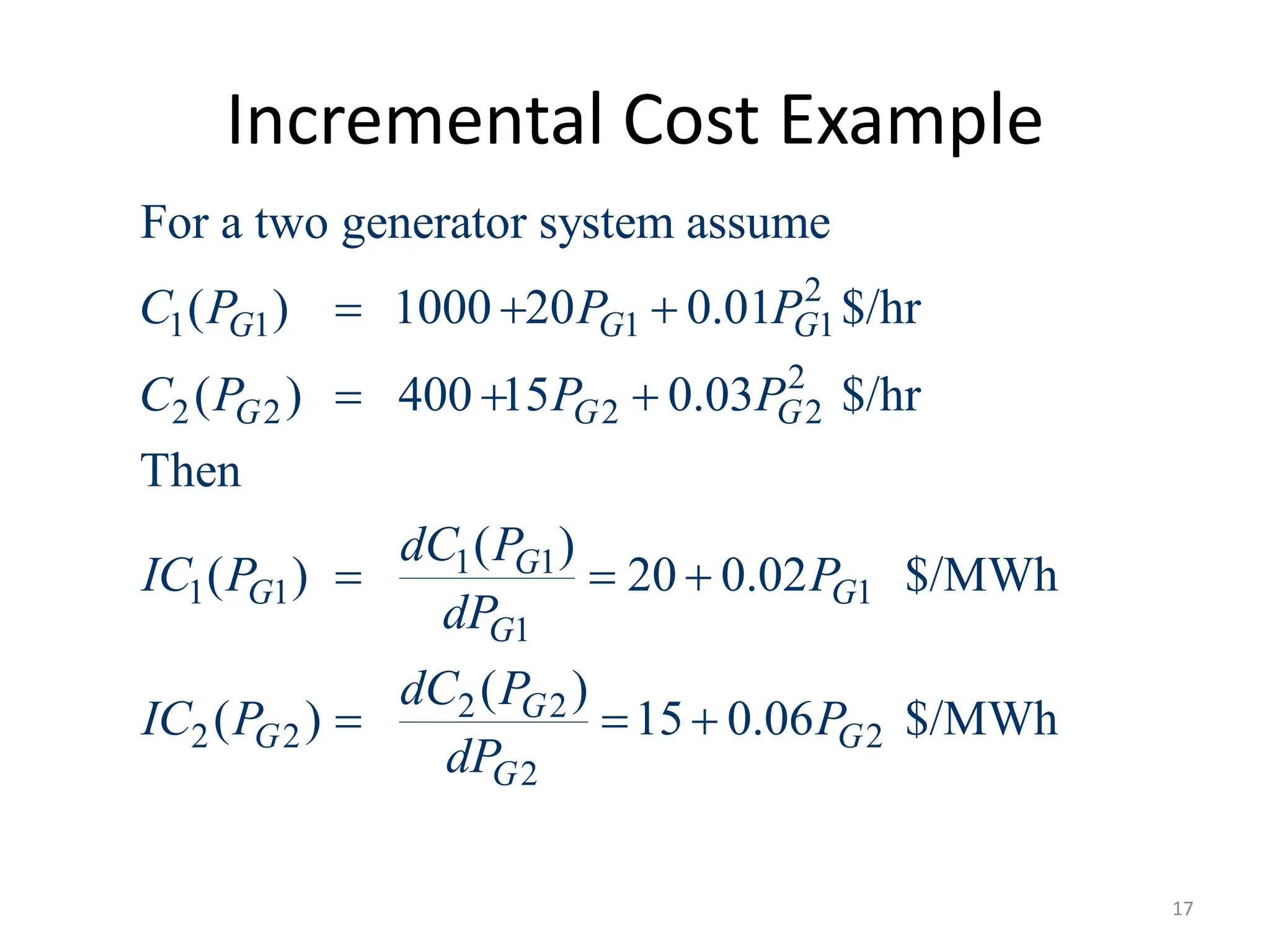

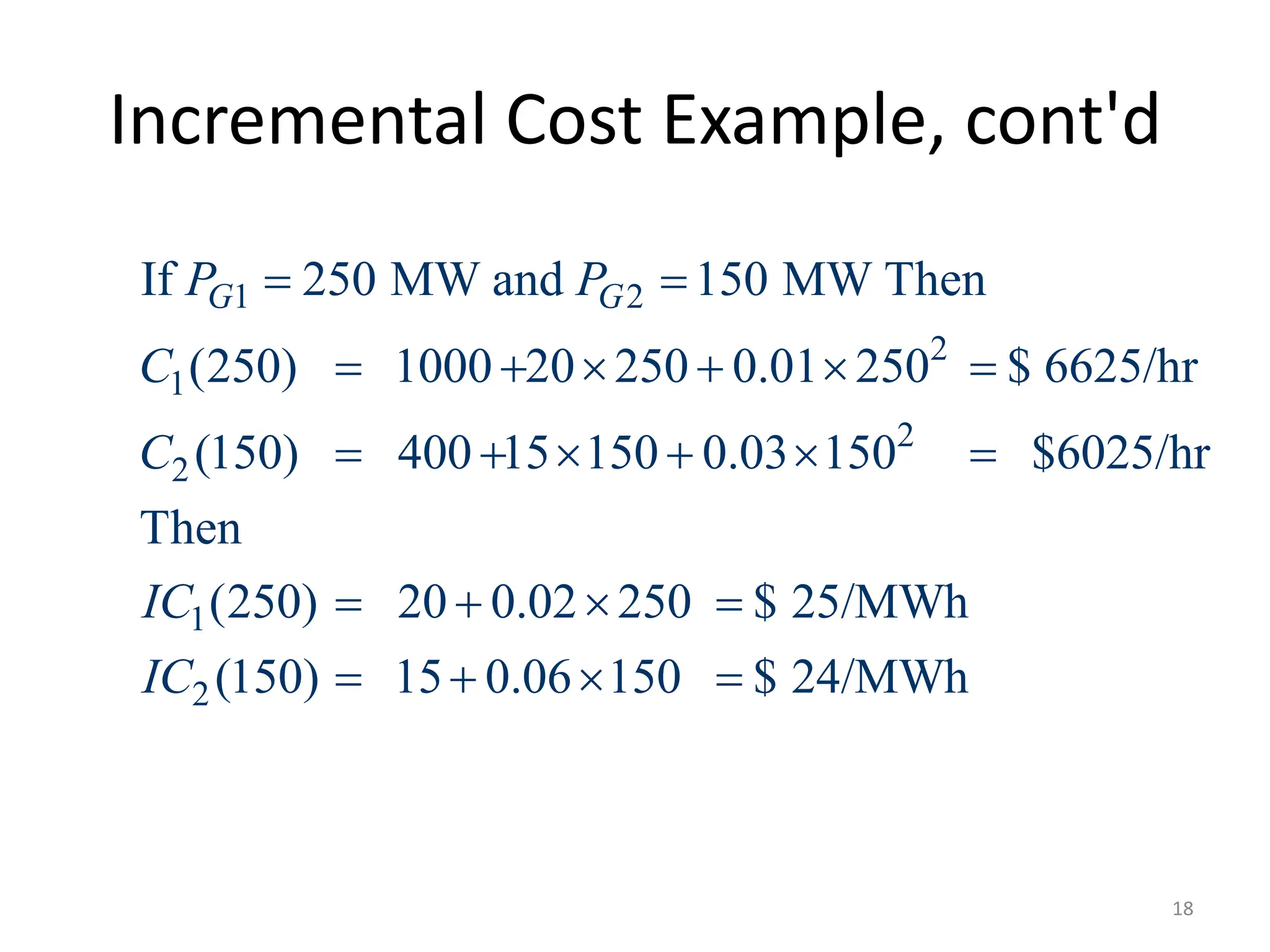

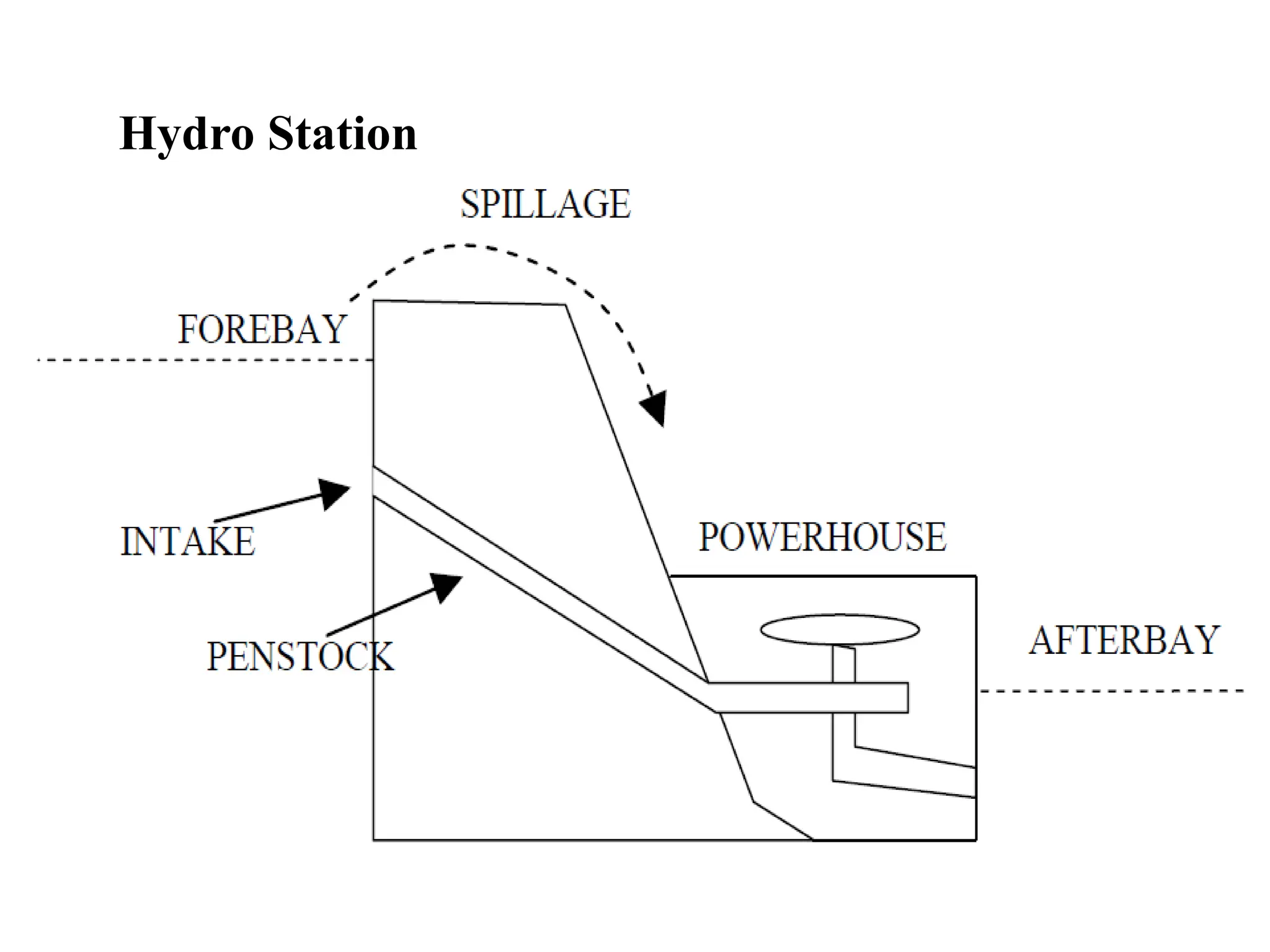

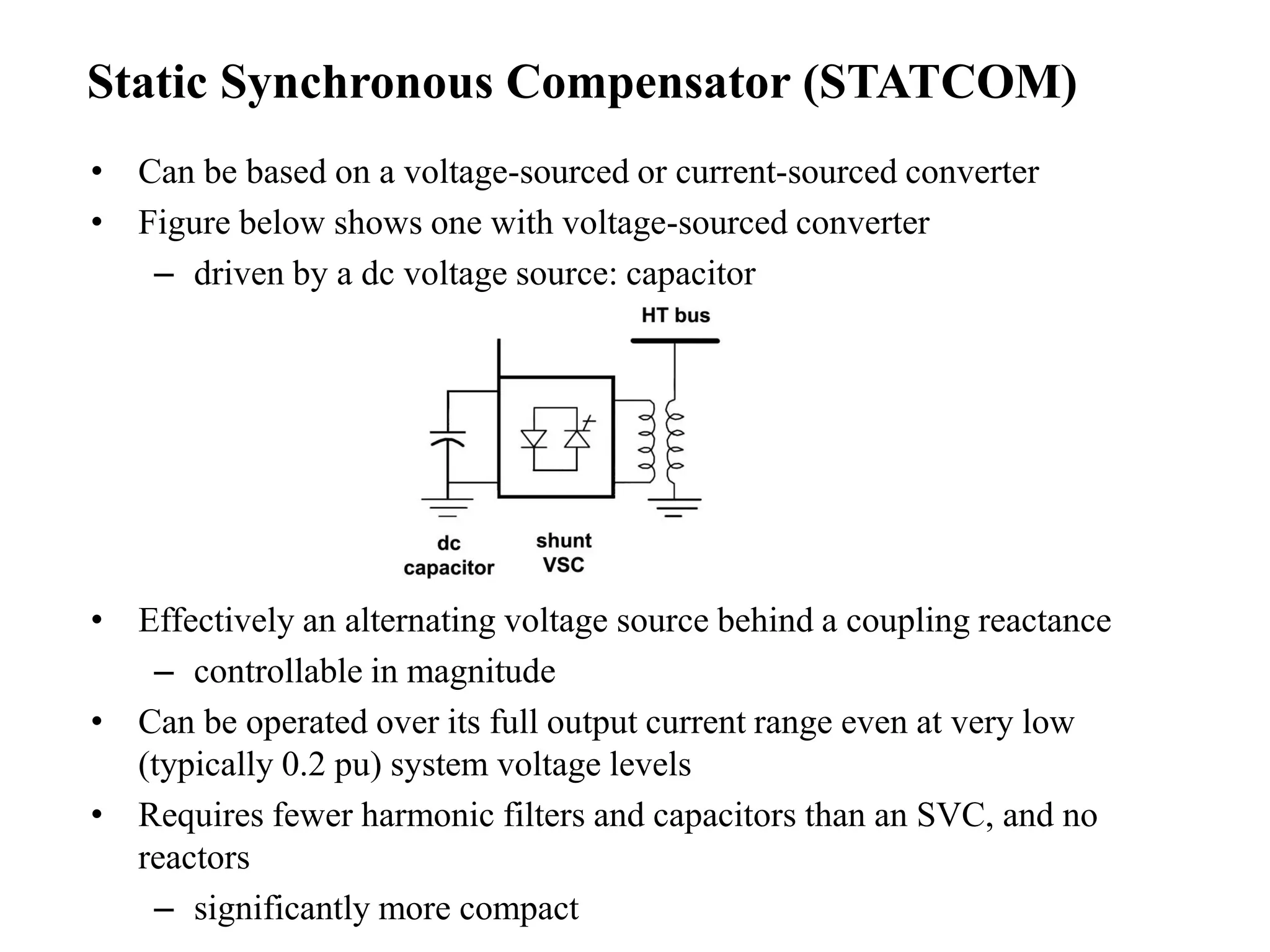

The document discusses the economic operation of power systems, focusing on the varying costs associated with different generation technologies, such as thermal and hydro. It explores how to minimize variable operating costs to meet cyclical power system loads, emphasizing thermal unit optimization and methods of hydro-thermal scheduling. Additionally, it covers voltage and reactive power control, highlighting the importance of various devices and strategies for maintaining system stability and efficiency.