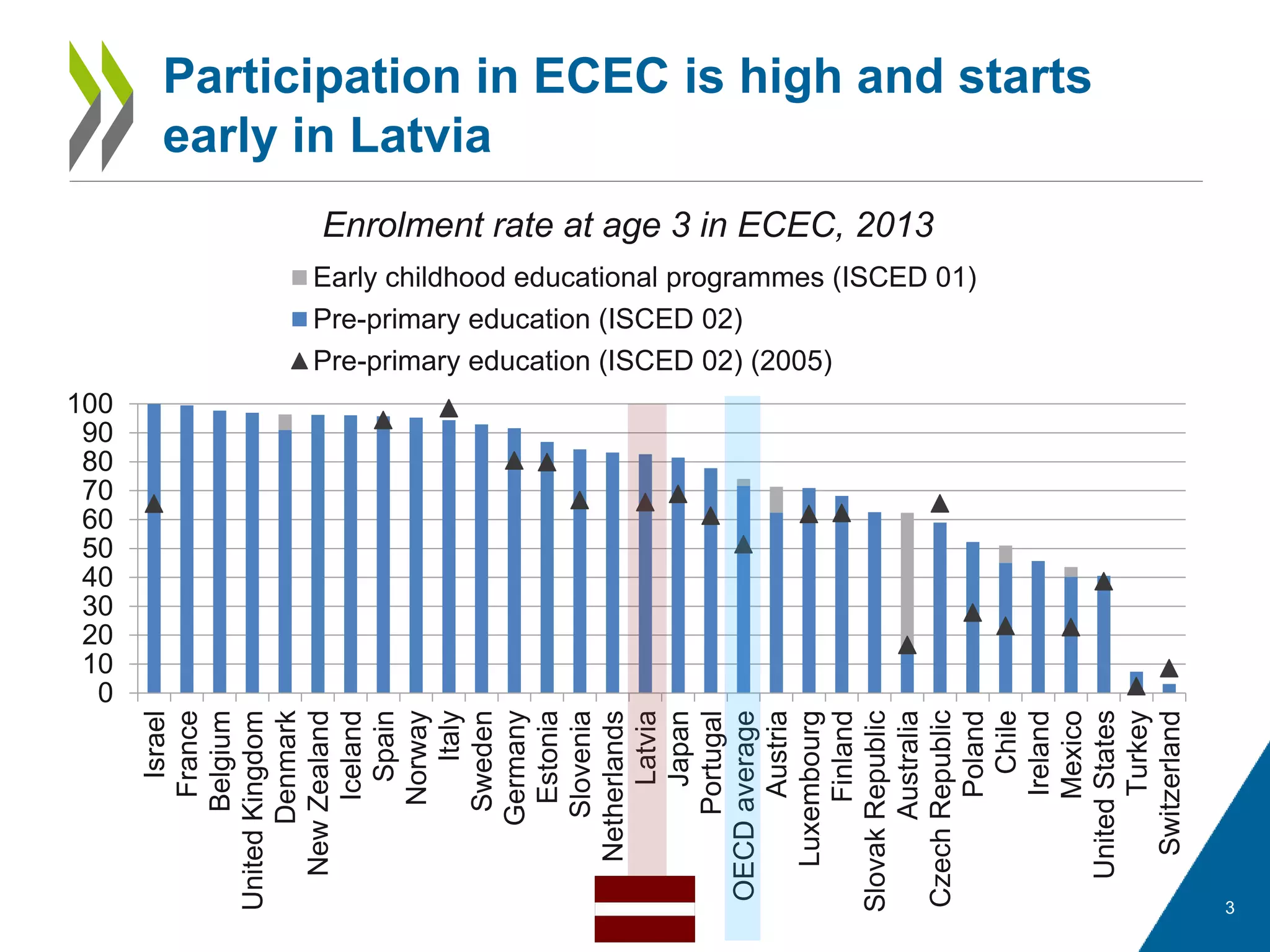

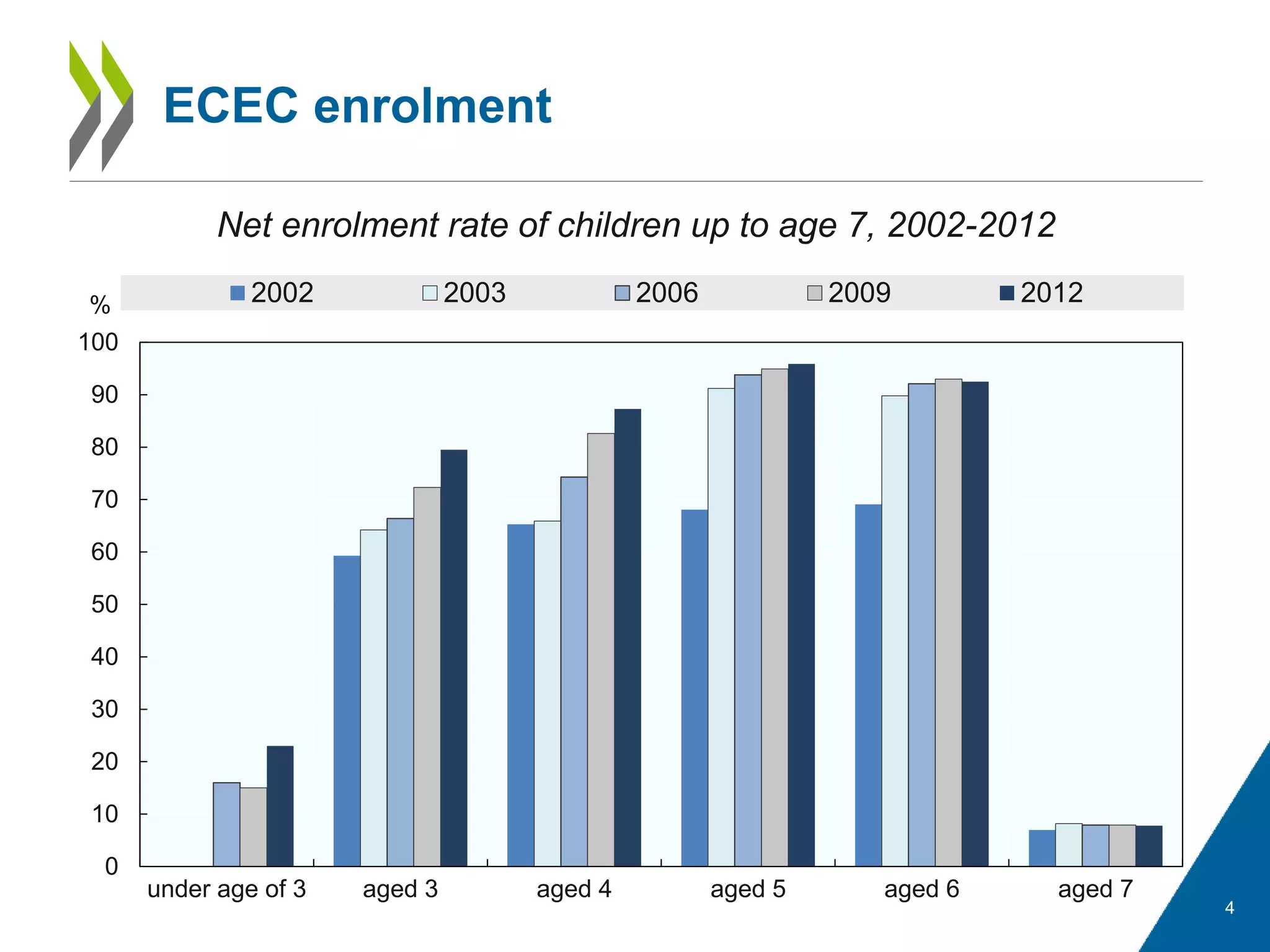

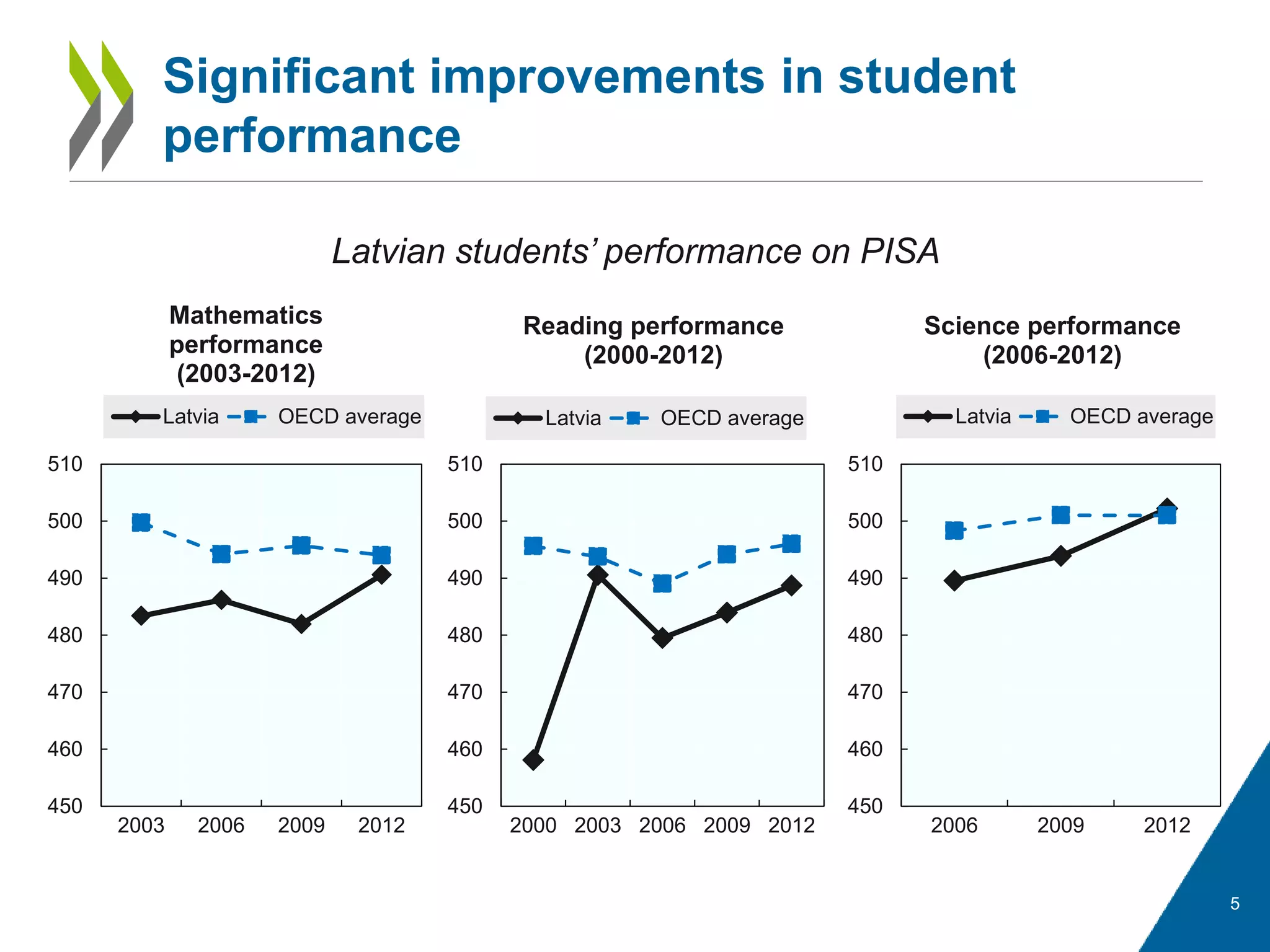

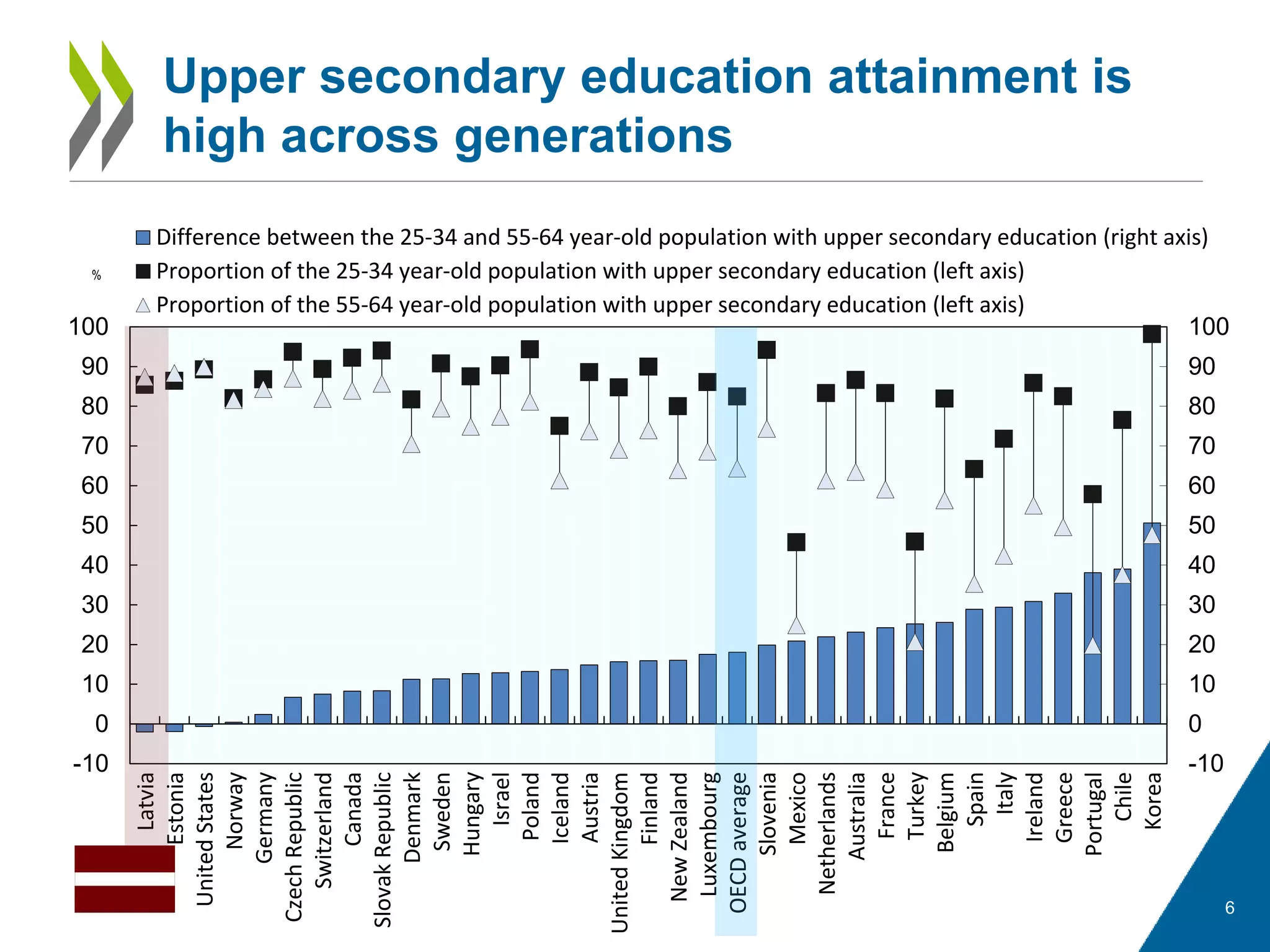

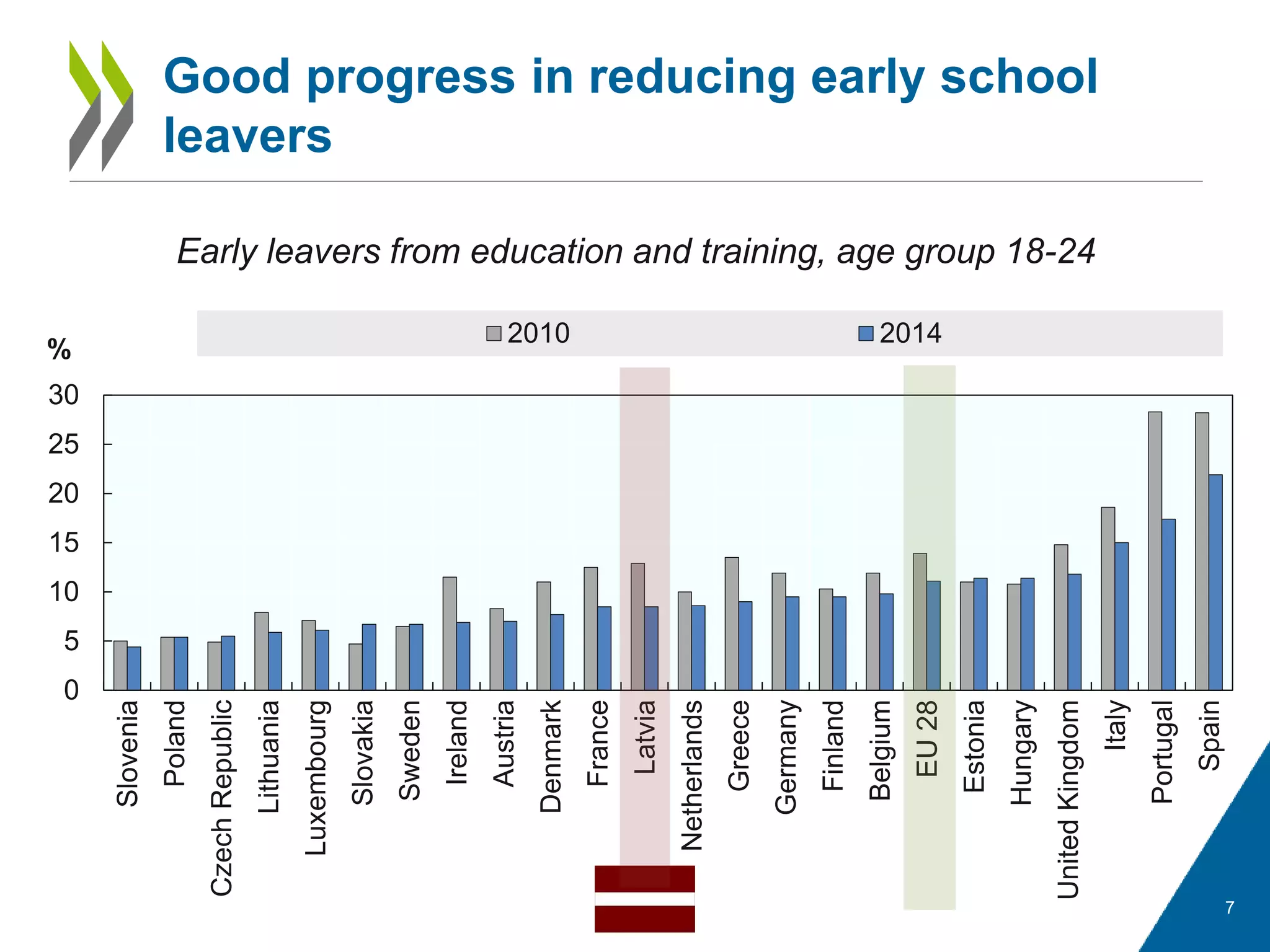

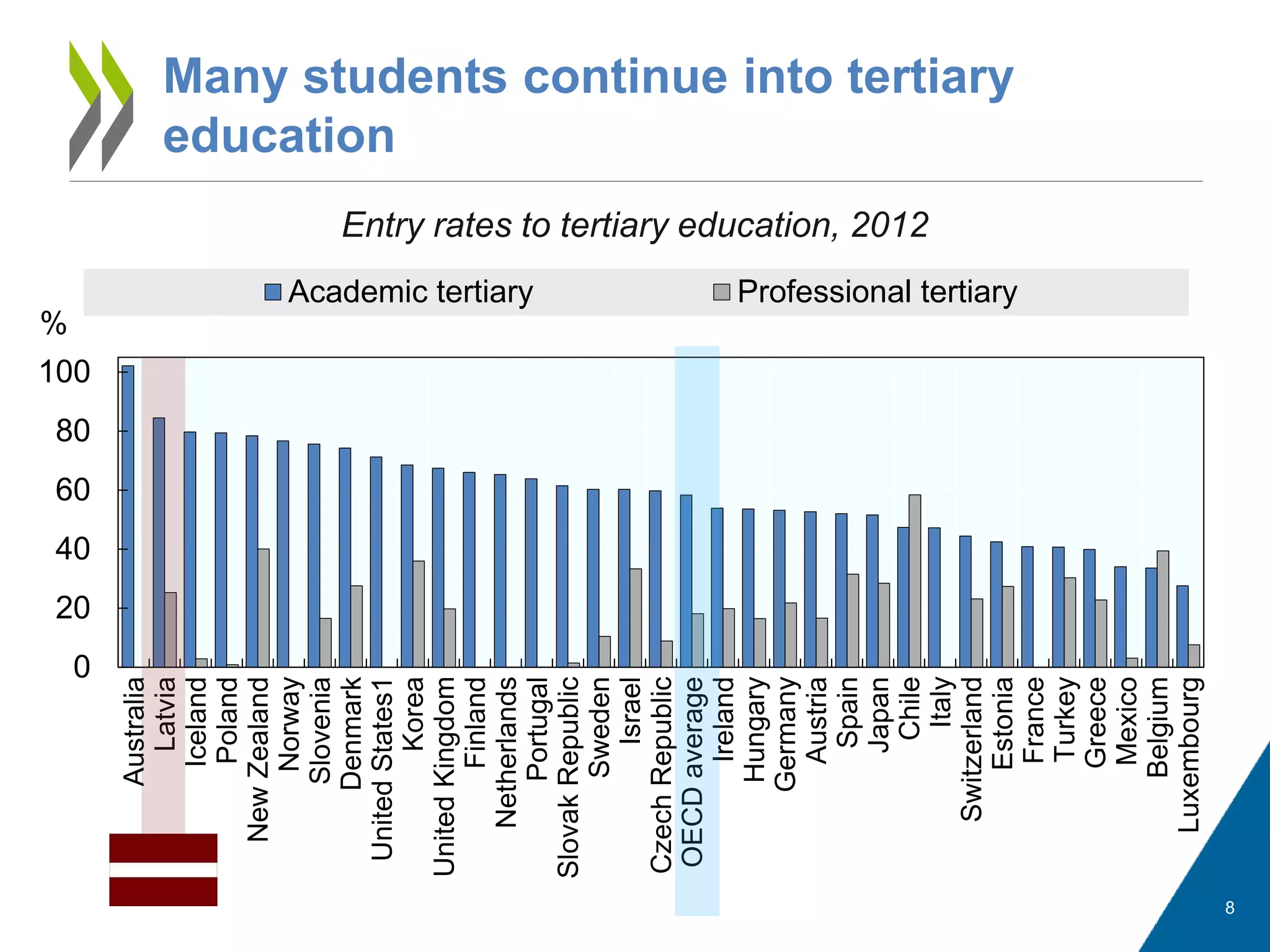

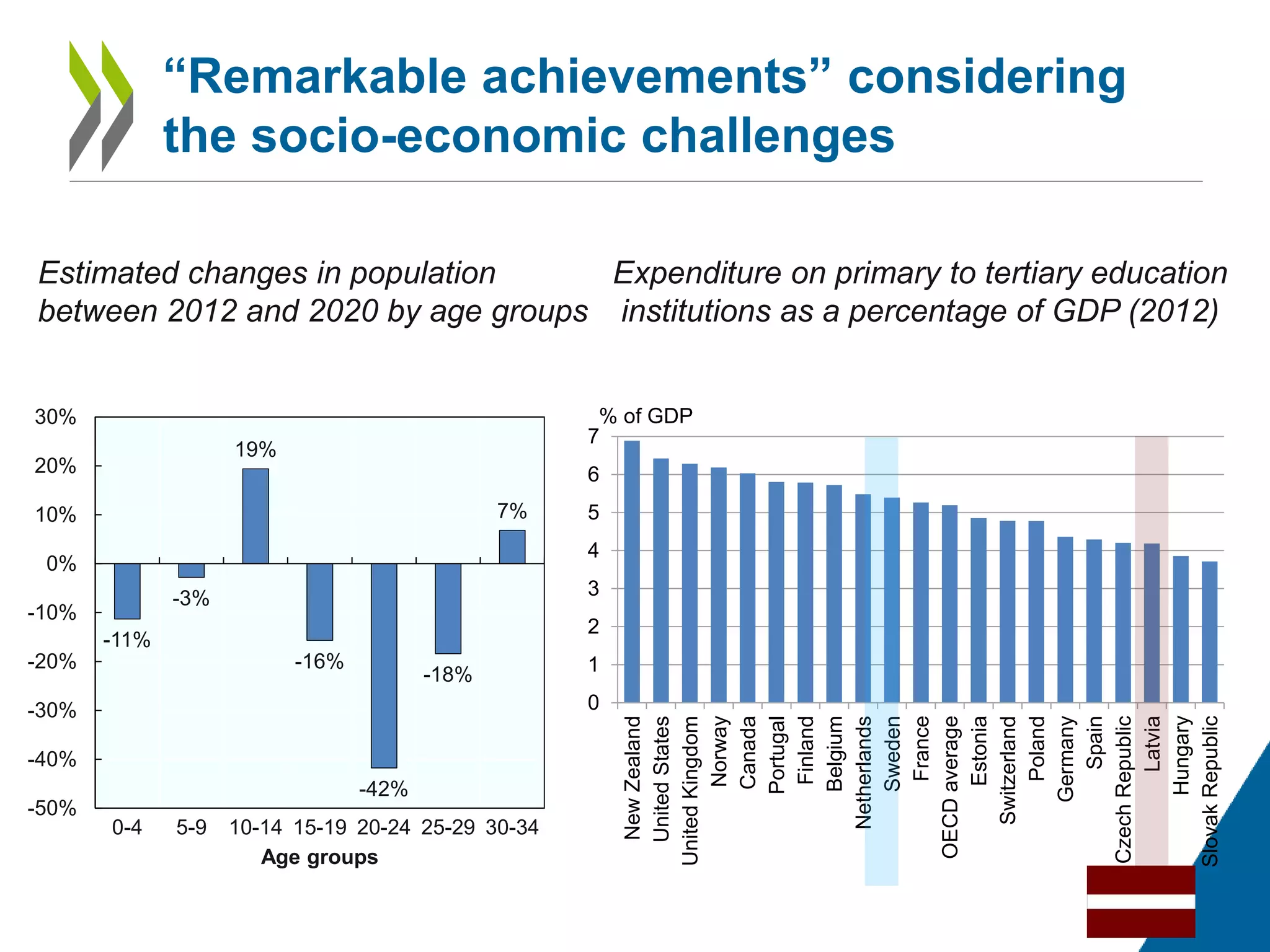

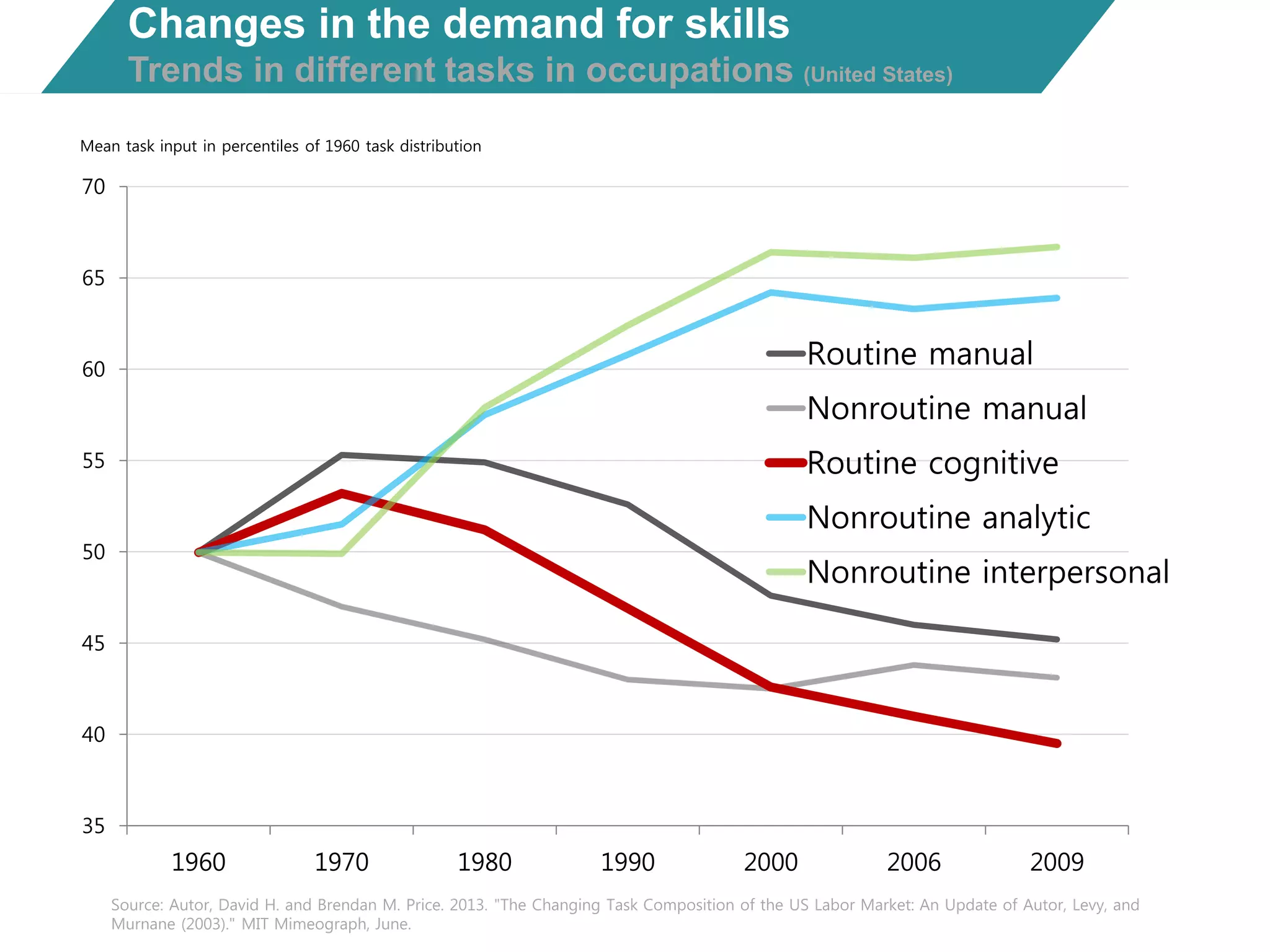

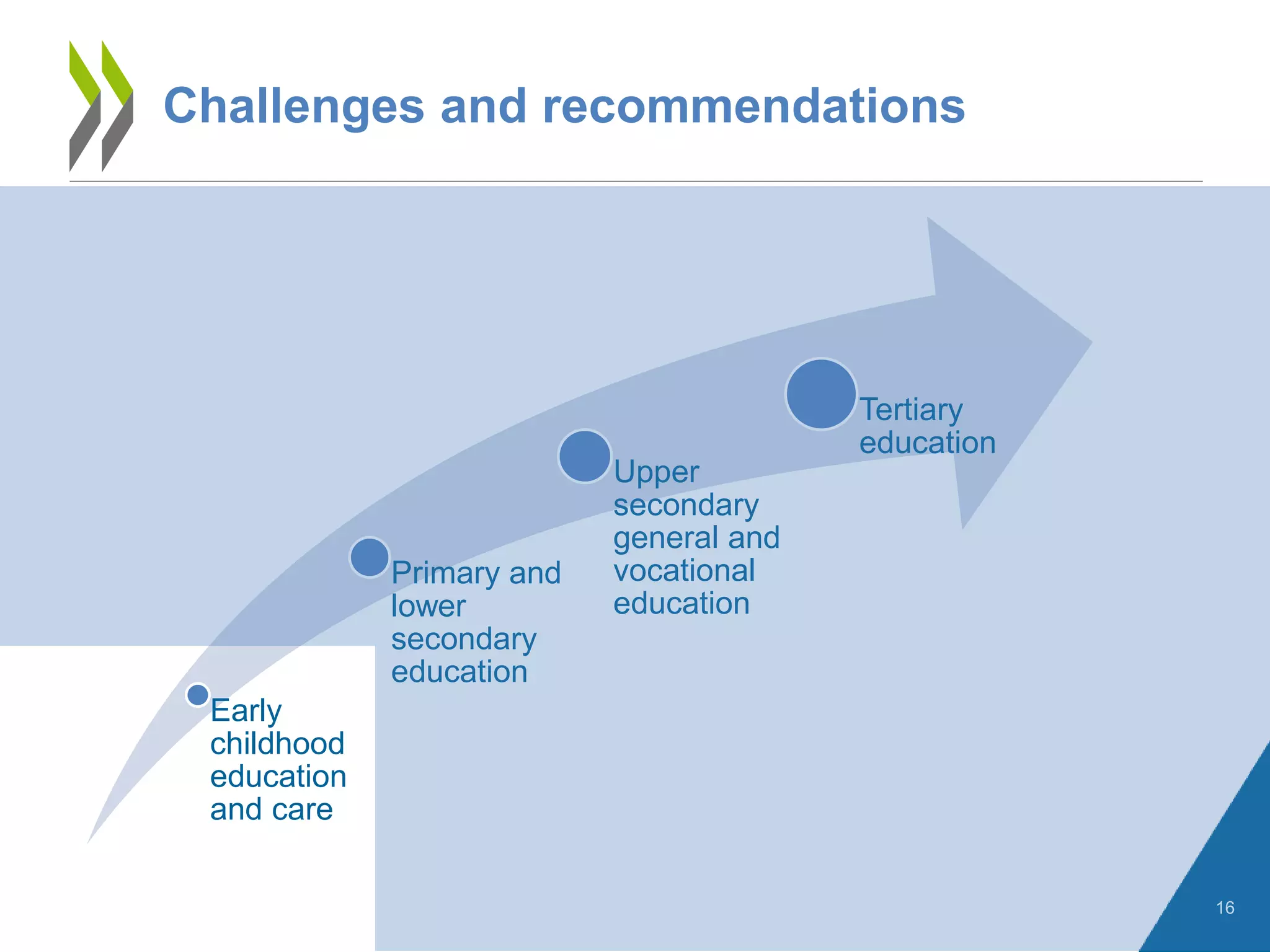

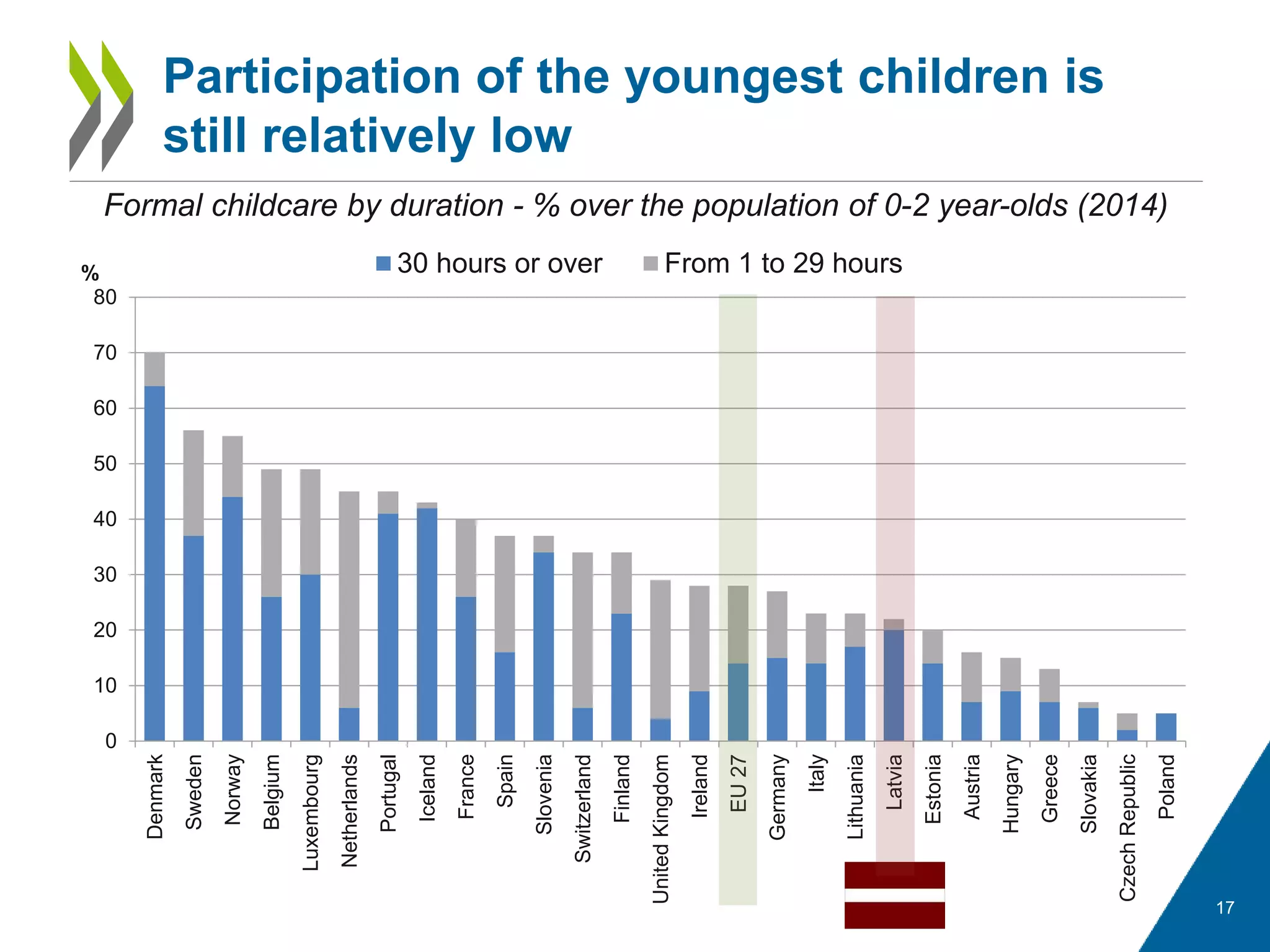

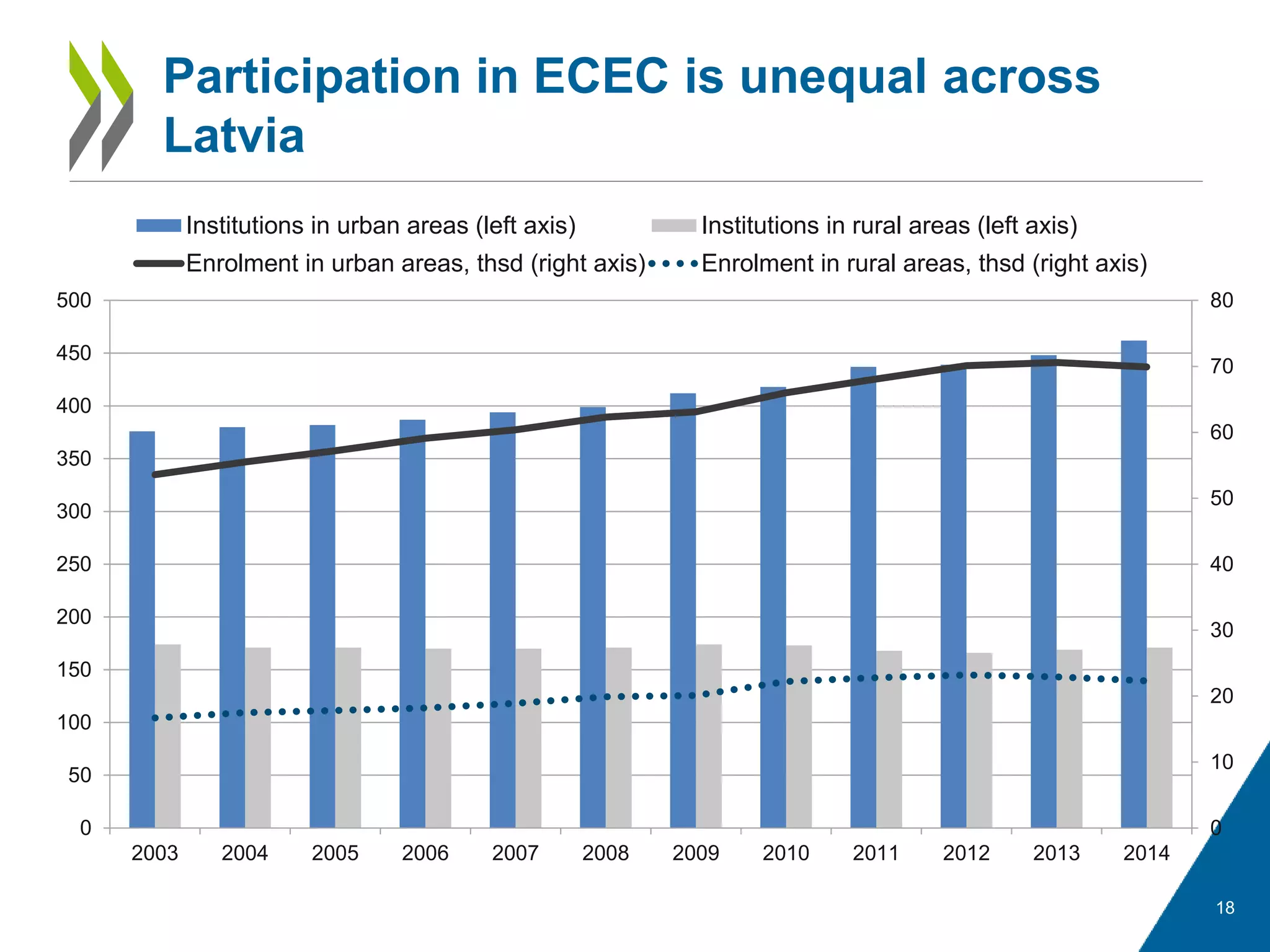

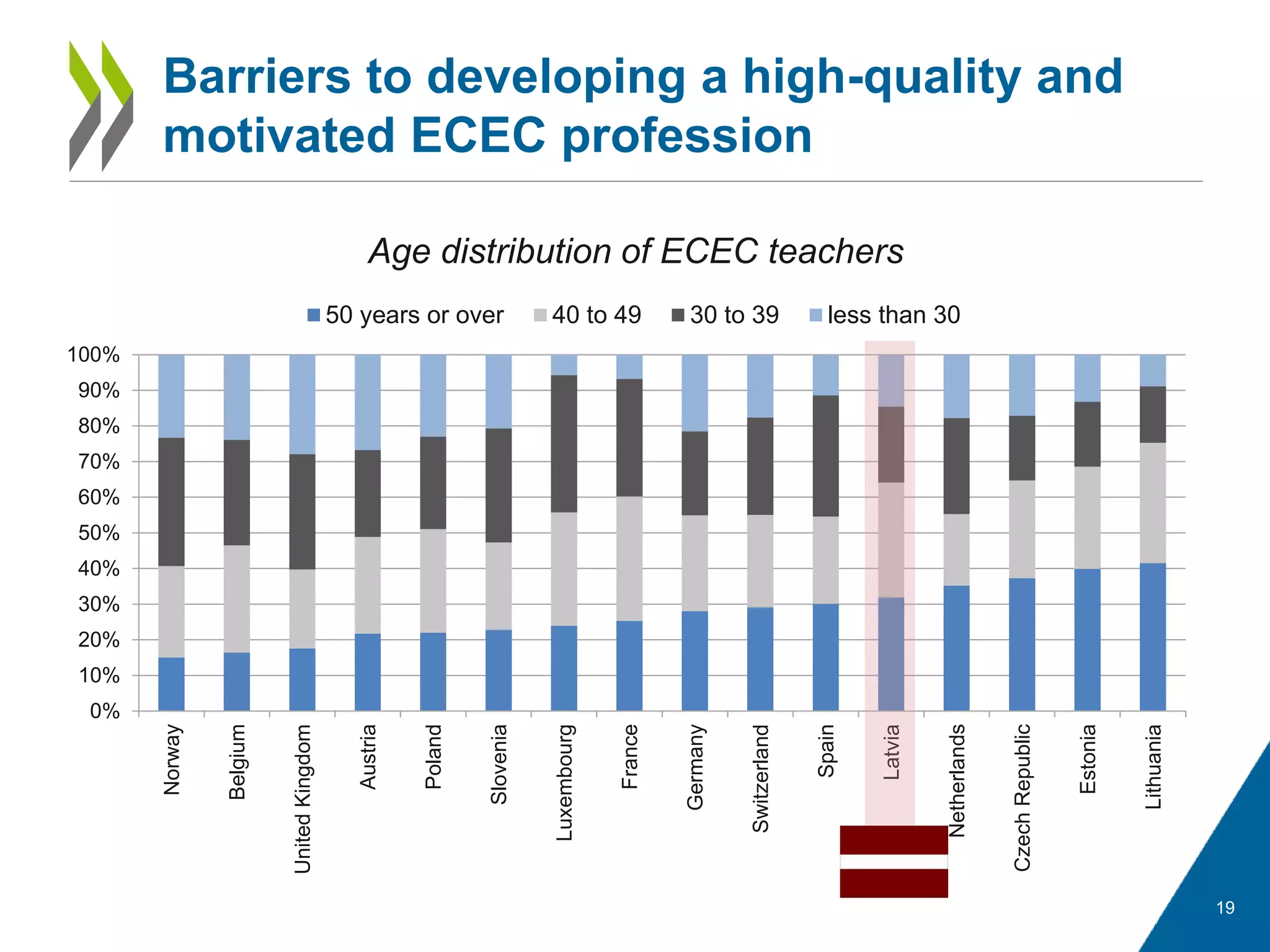

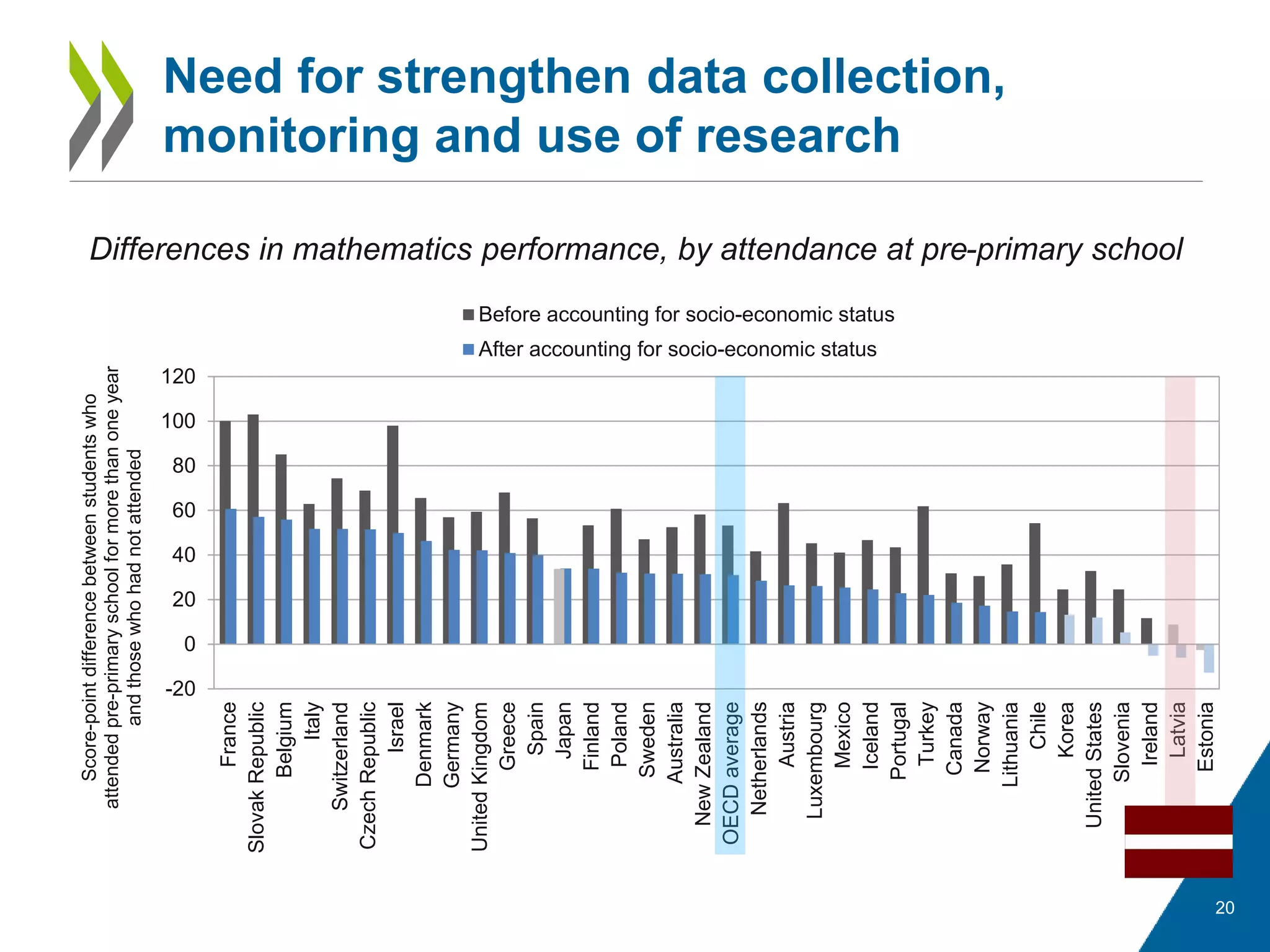

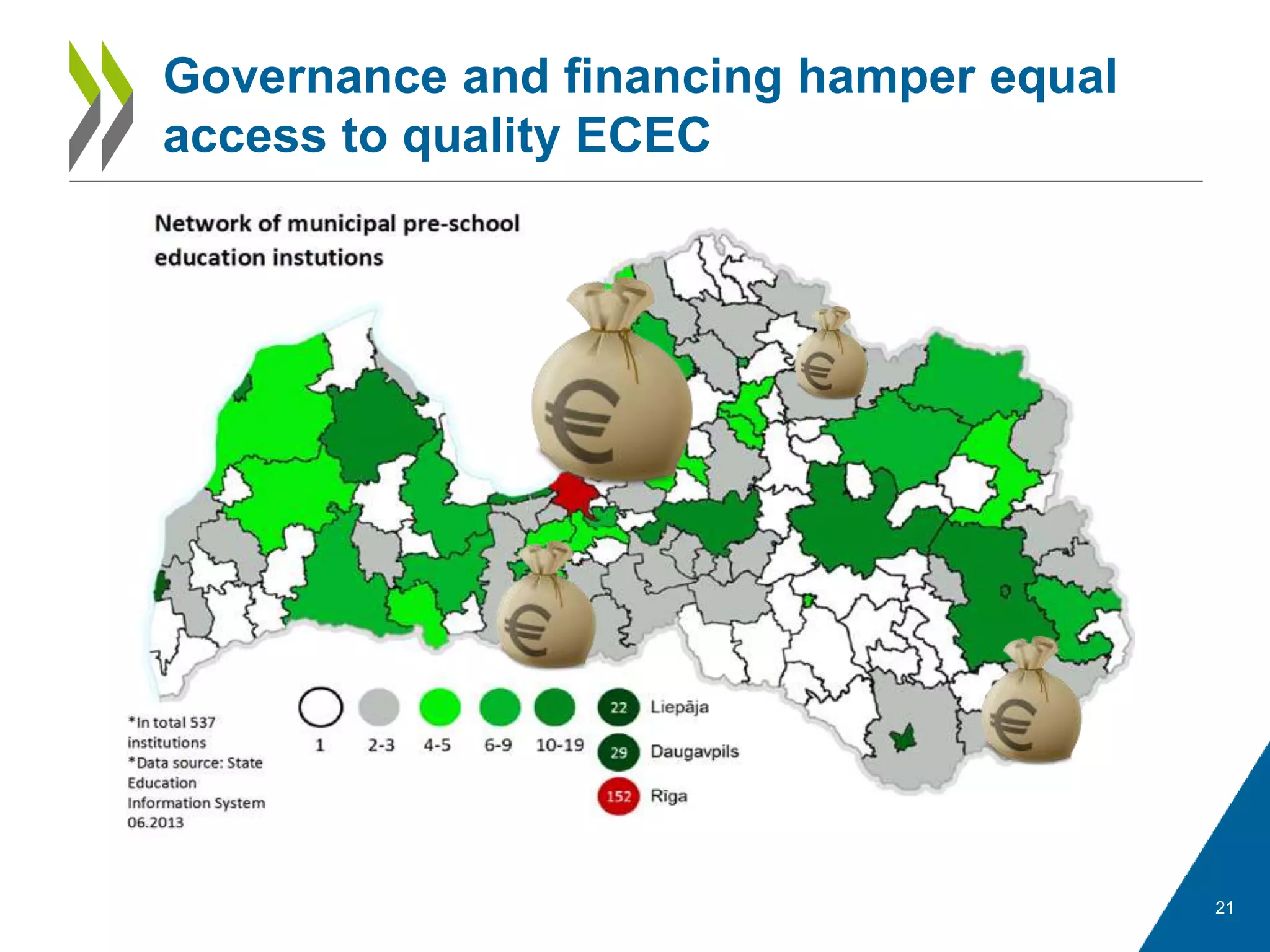

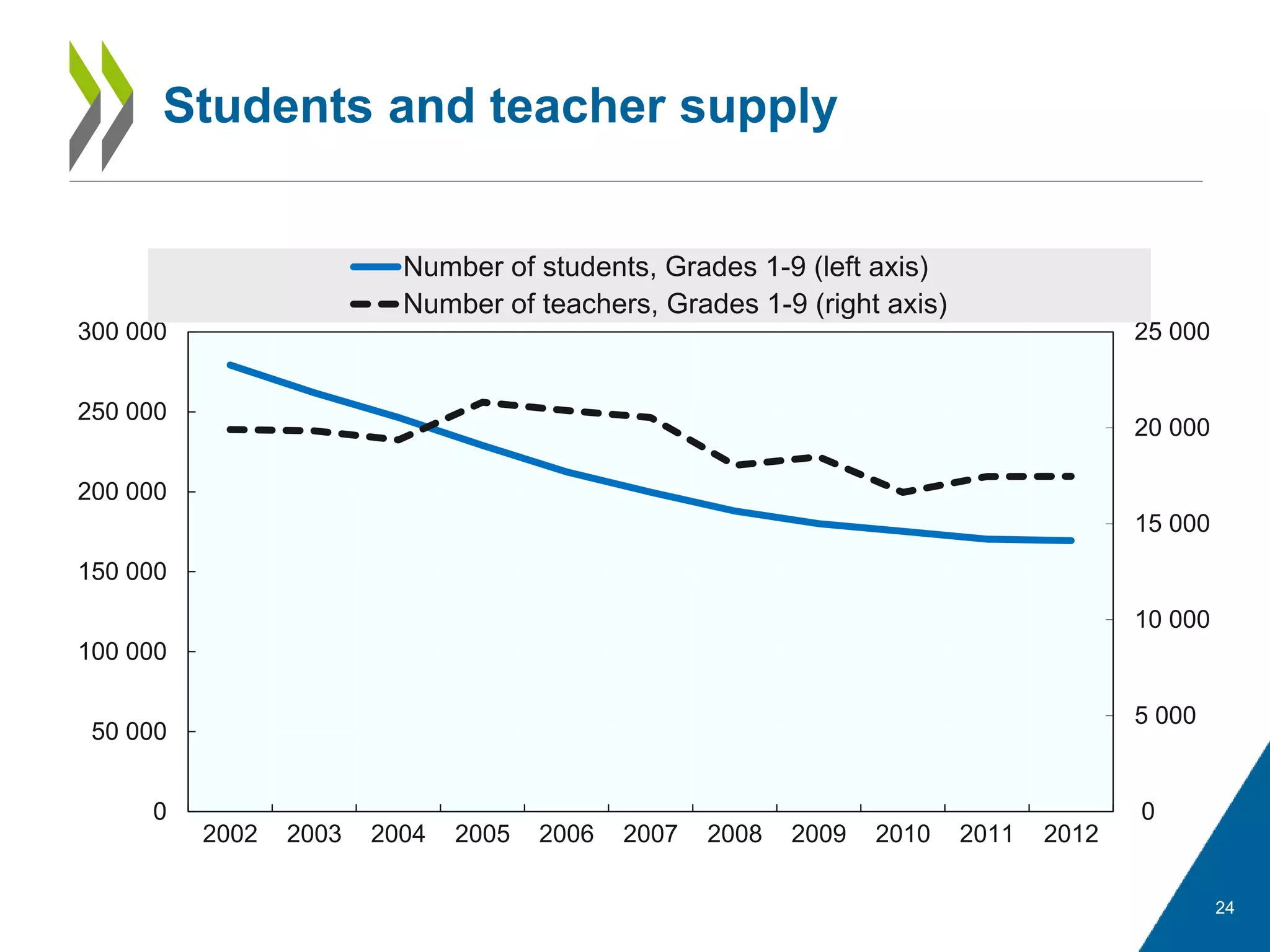

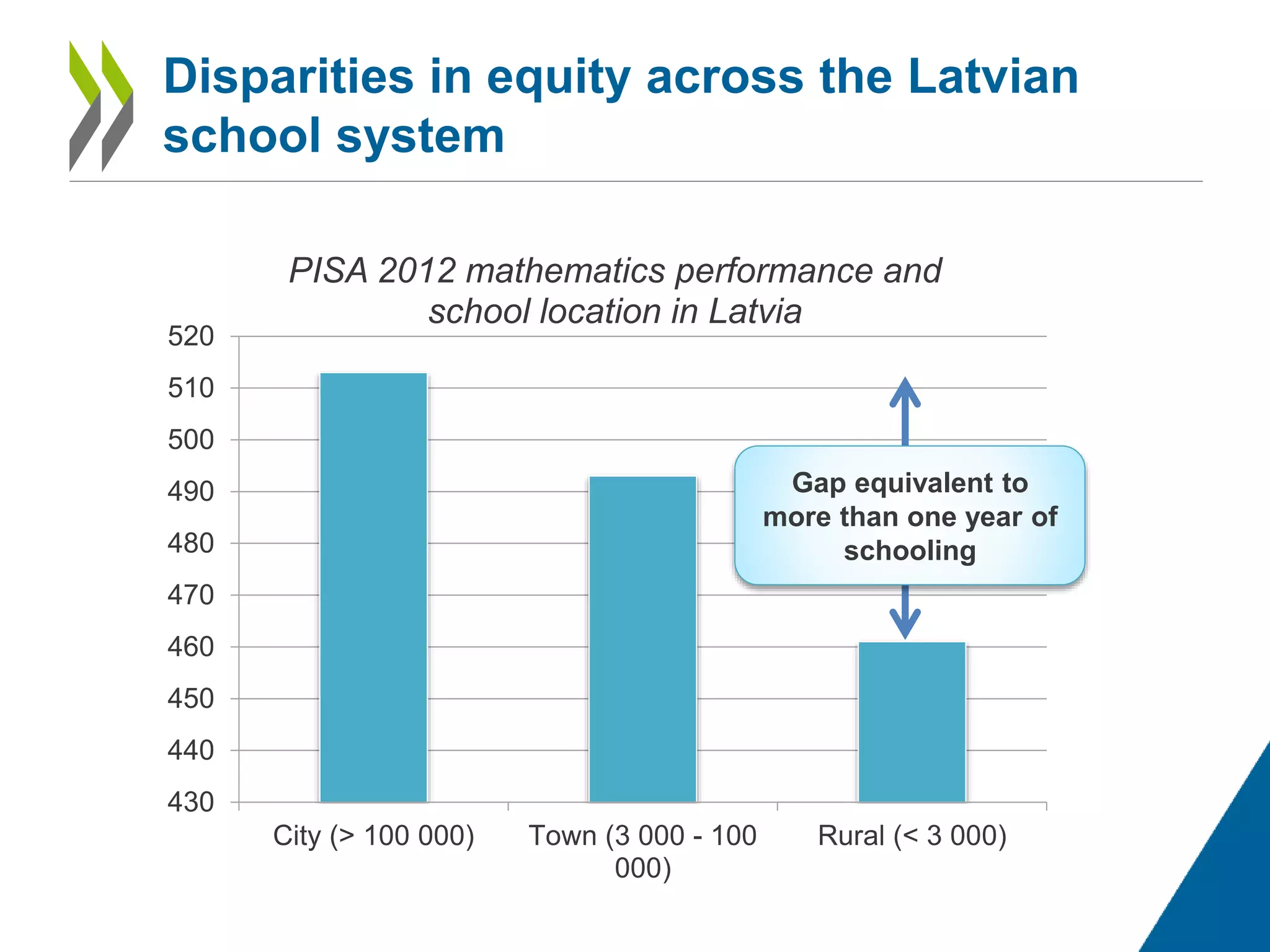

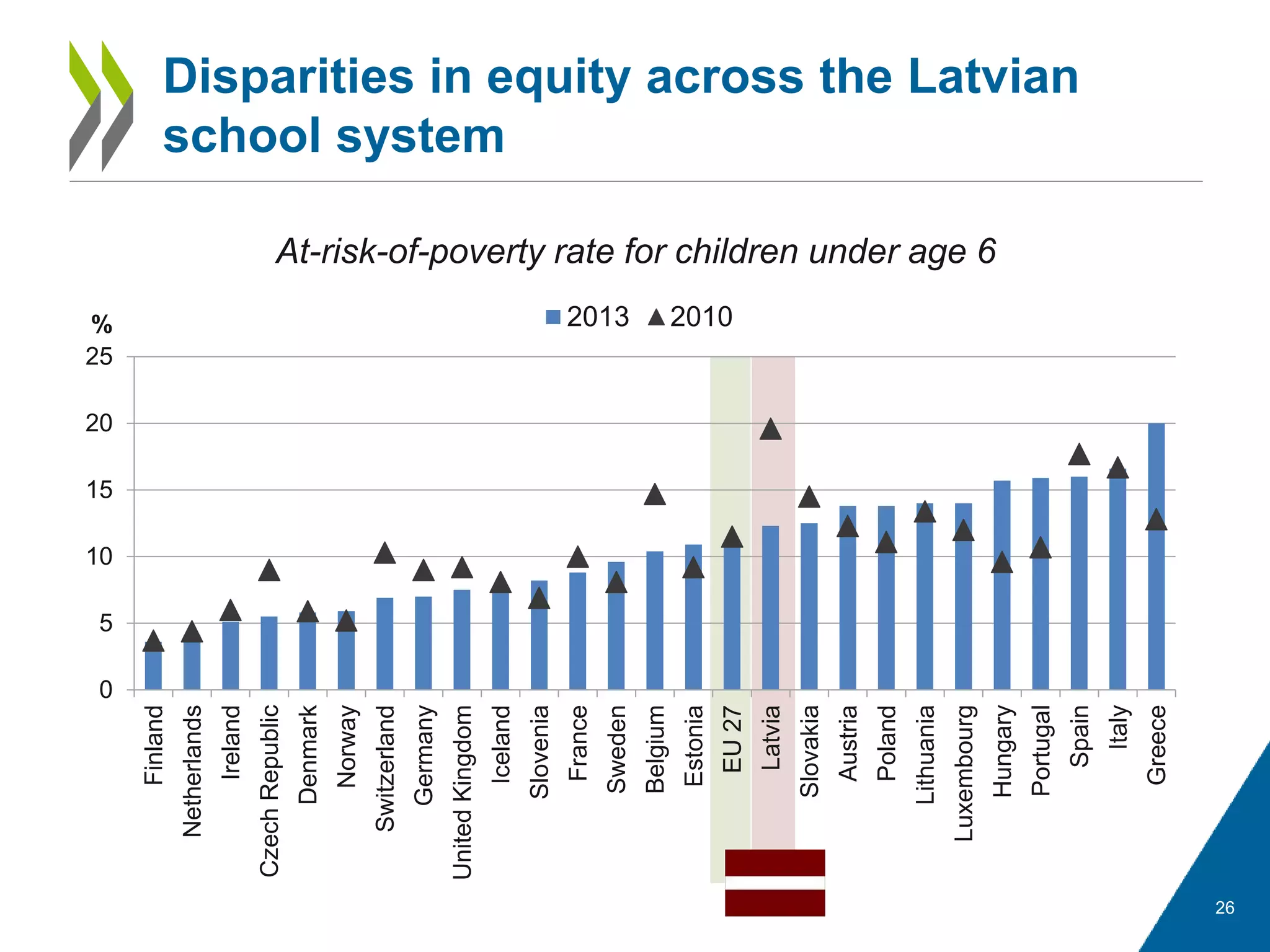

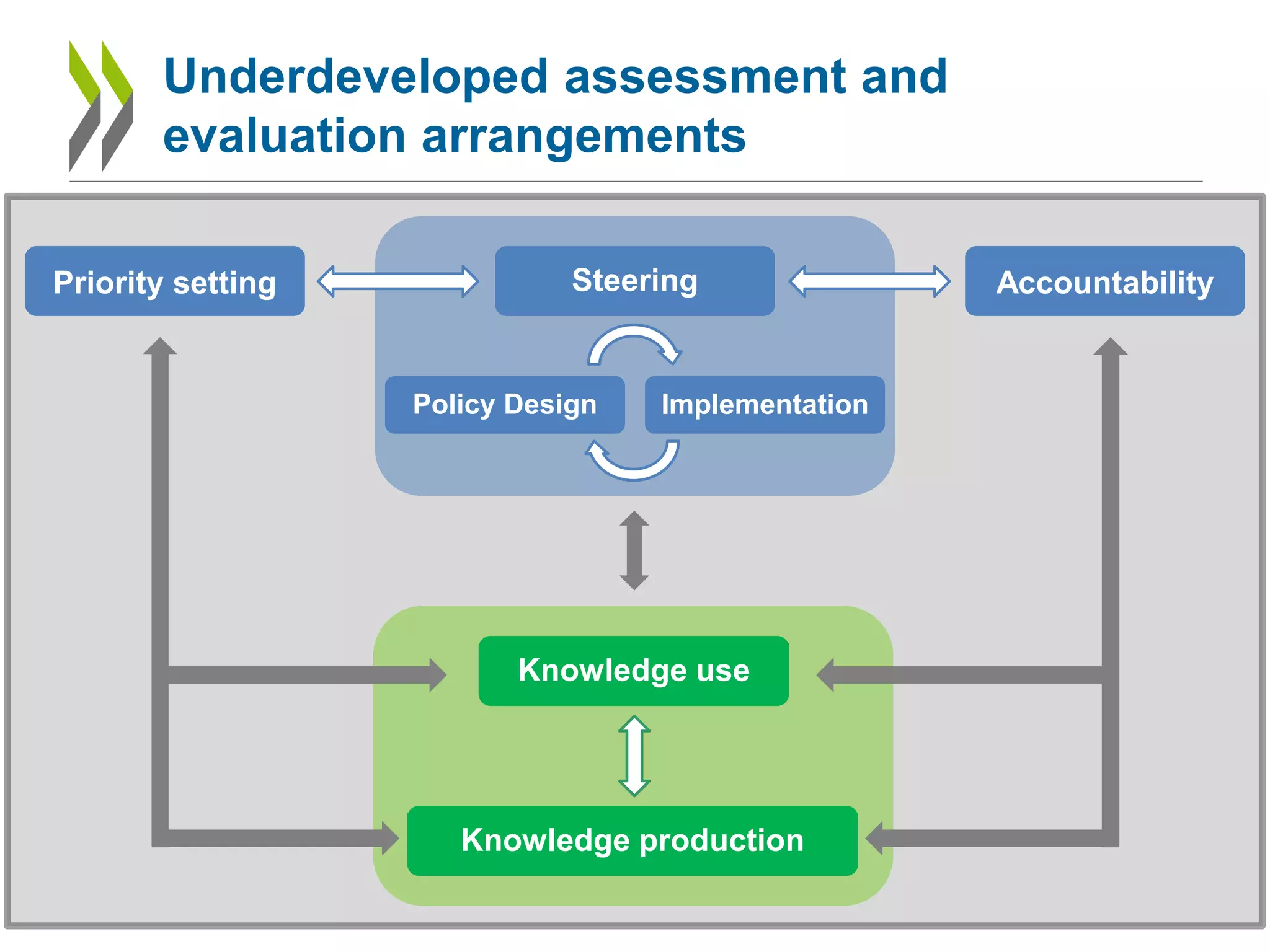

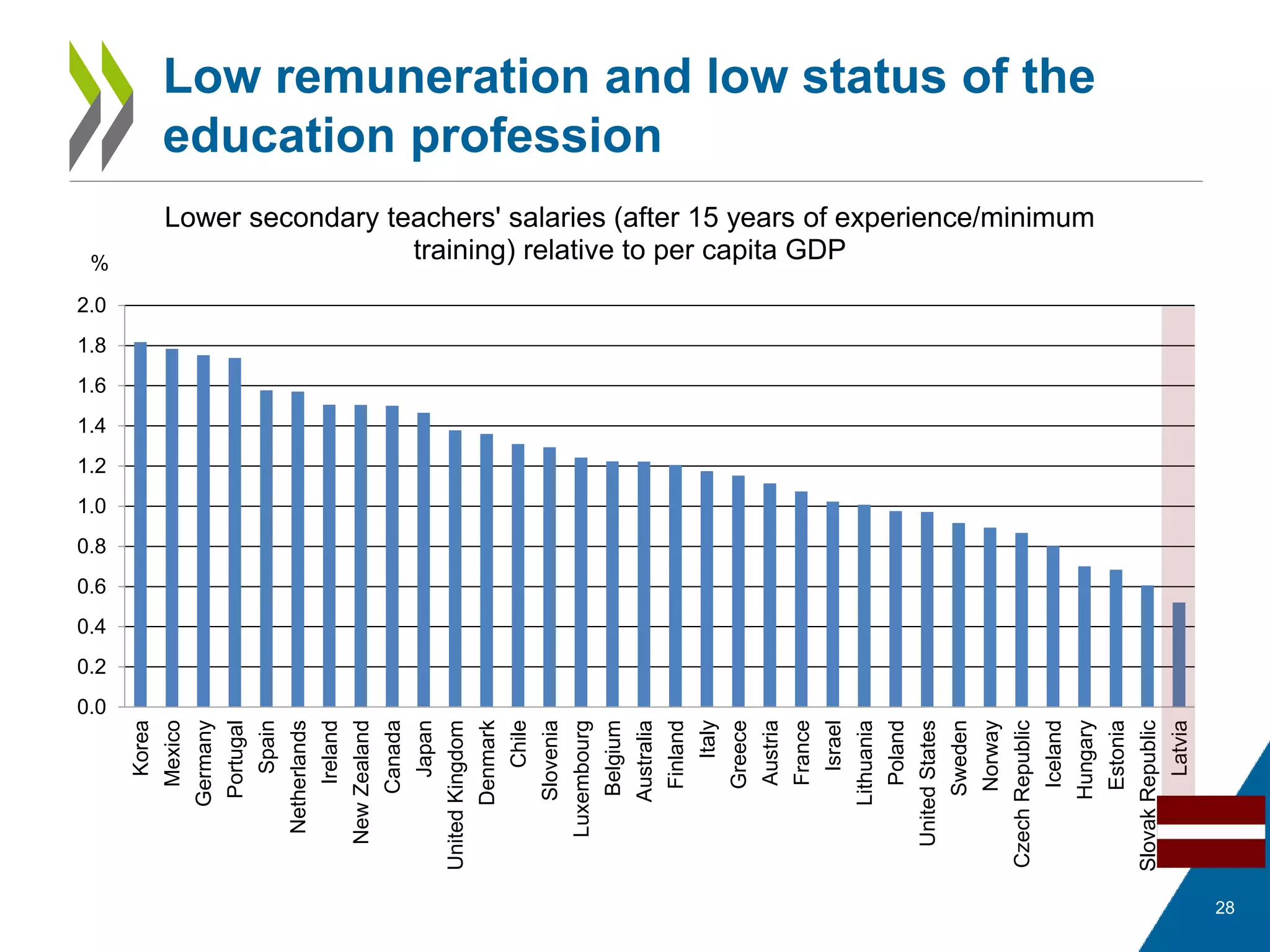

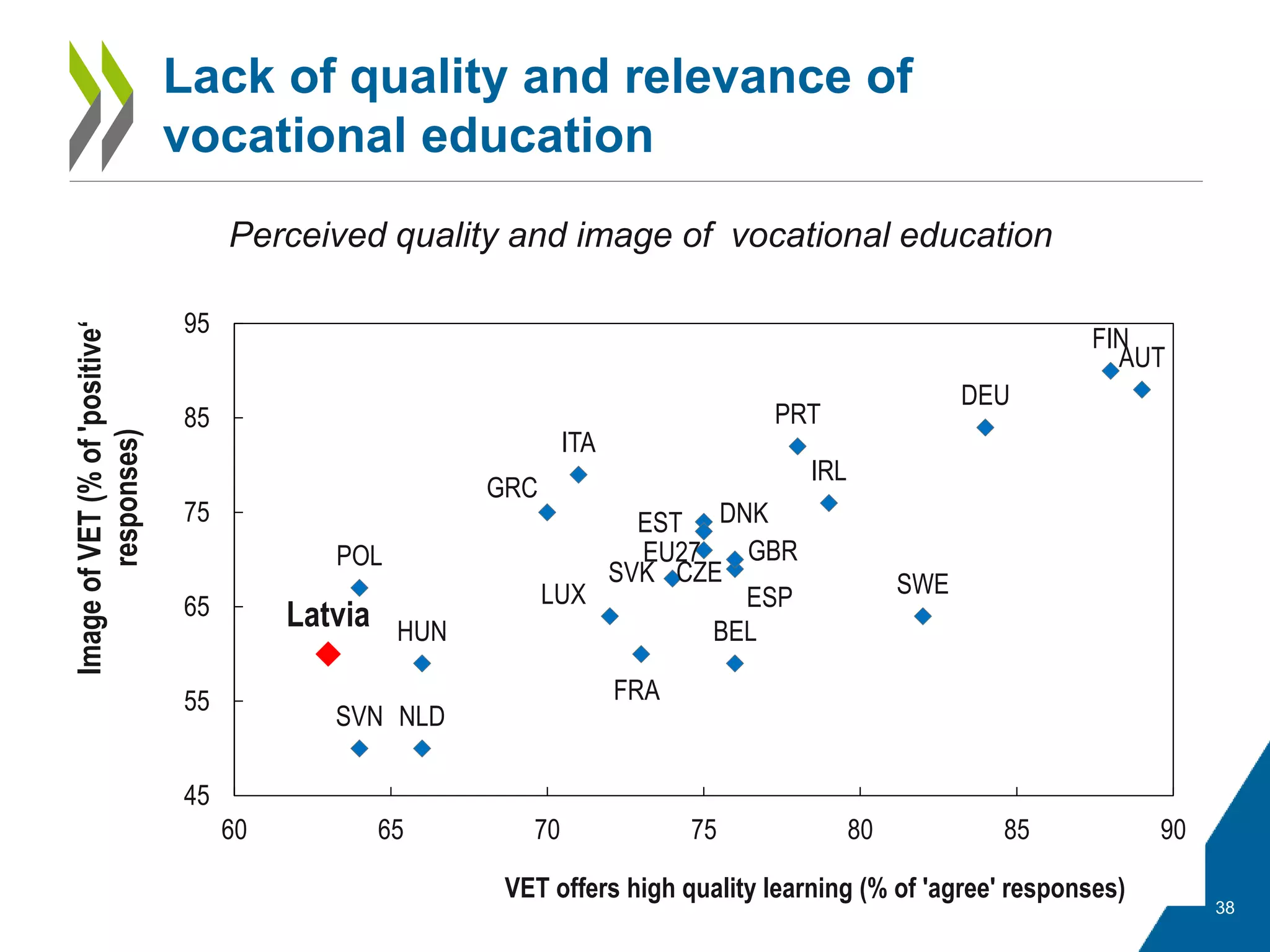

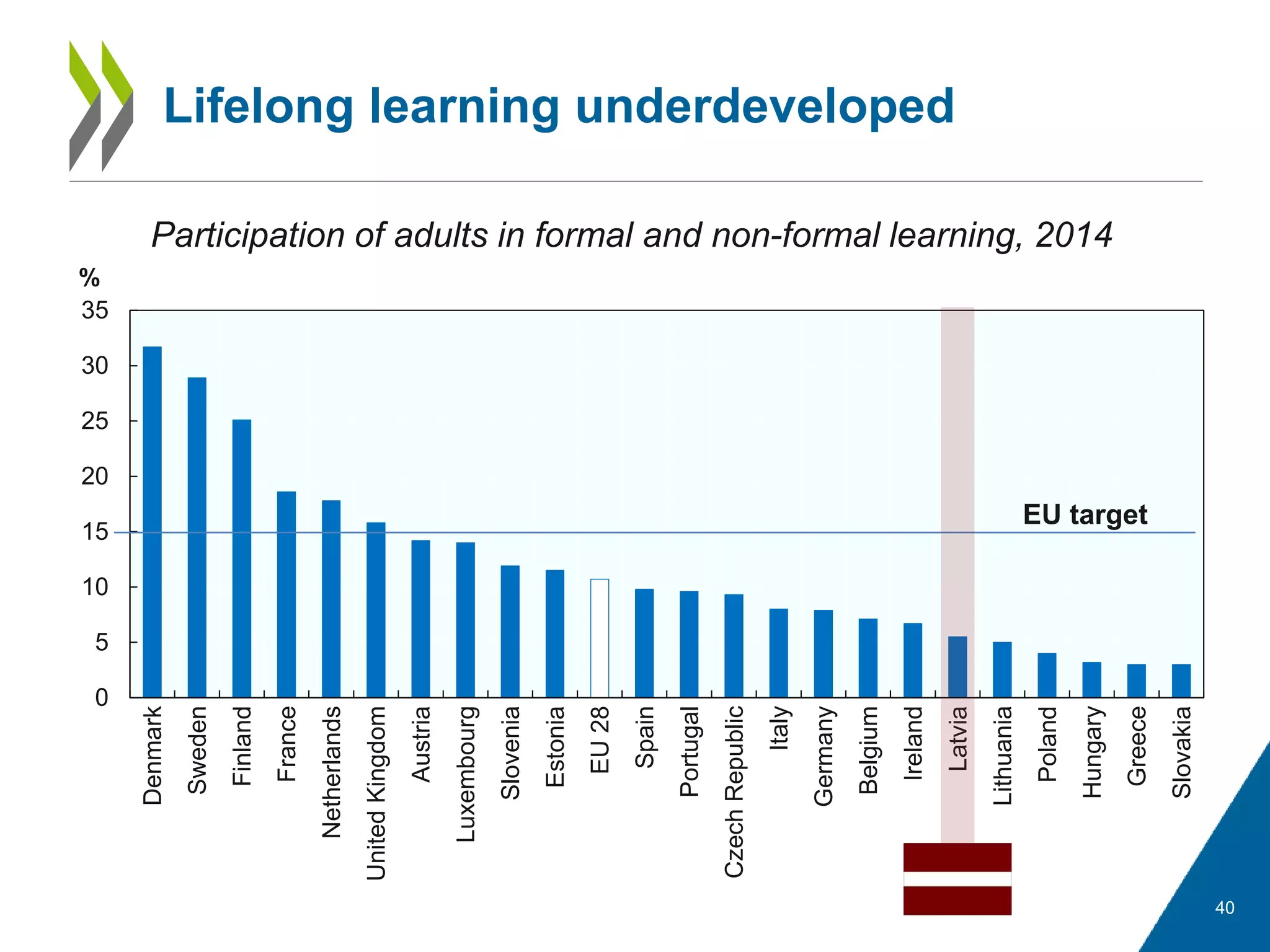

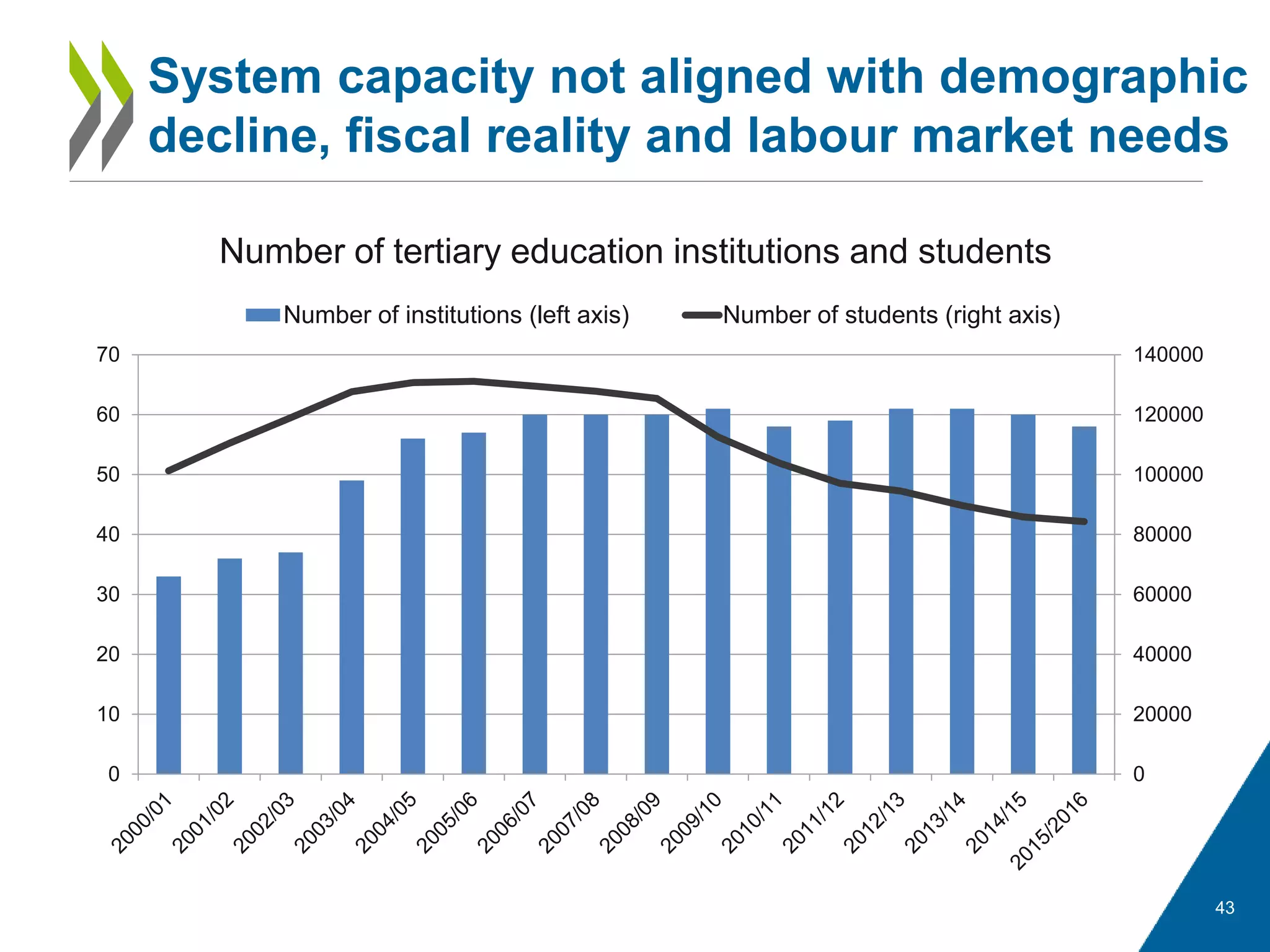

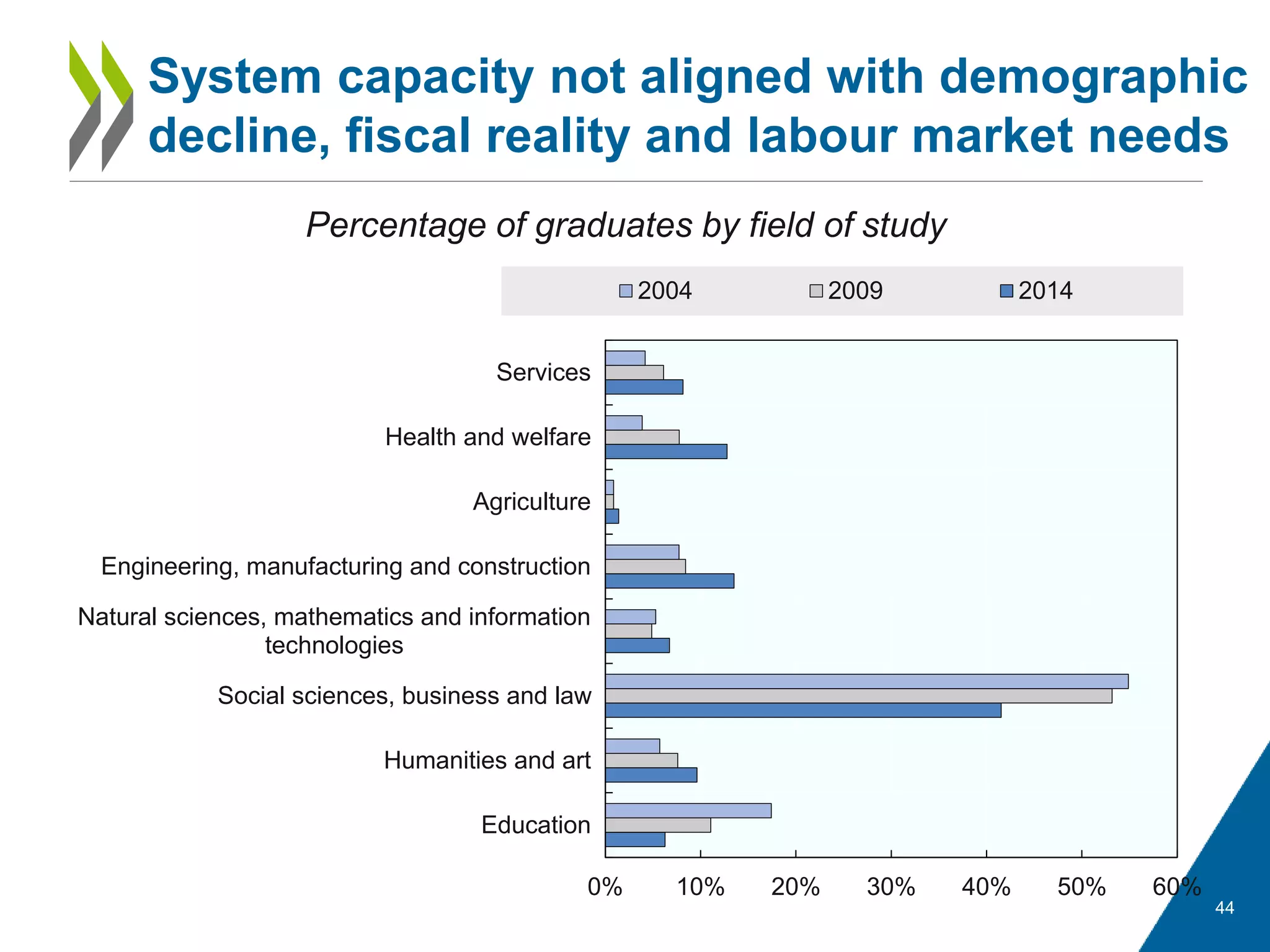

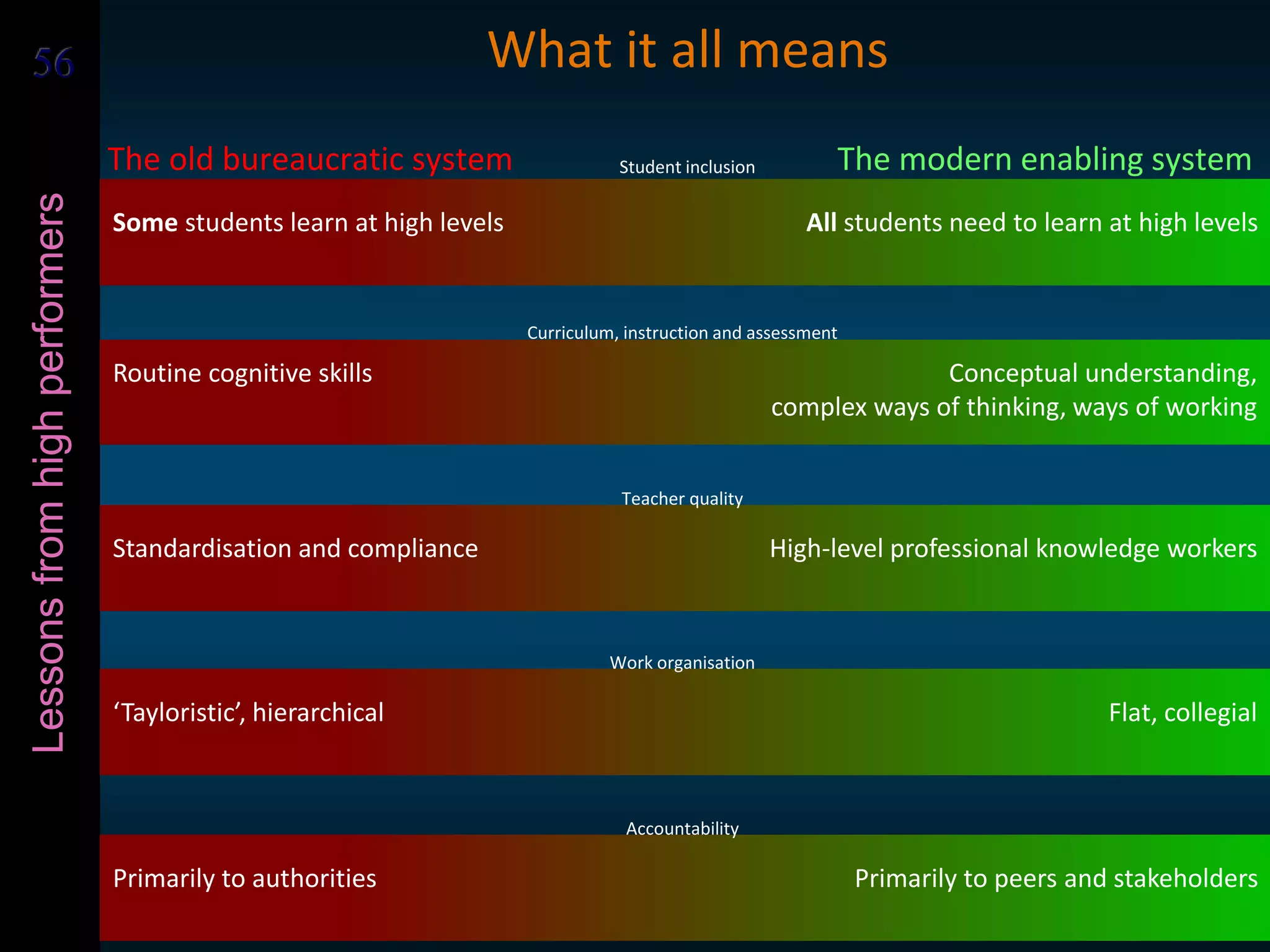

The OECD review highlights Latvia's significant progress in early childhood education, student performance, and upper secondary education attainment, acknowledging the high enrollment rates and improvements in mathematics, reading, and science. It presents ongoing challenges such as regional disparities in education access, low participation in lifelong learning, and the need for reform in vocational education's quality and relevance. Recommendations include enhancing early childhood education services, improving vocational education initiatives, and developing coherent assessment and evaluation frameworks for better educational outcomes.