The document outlines topics in the economics of uncertainty, focusing on expected utility theory, mean-variance optimization, and insurance. It covers fundamental concepts such as risk attitudes, risk aversion measures, and the capital asset pricing model, along with mathematical models like the St. Petersburg paradox and the Allais paradox. The document serves as a comprehensive guide for analyzing decision-making under uncertainty and optimizing investment portfolios.

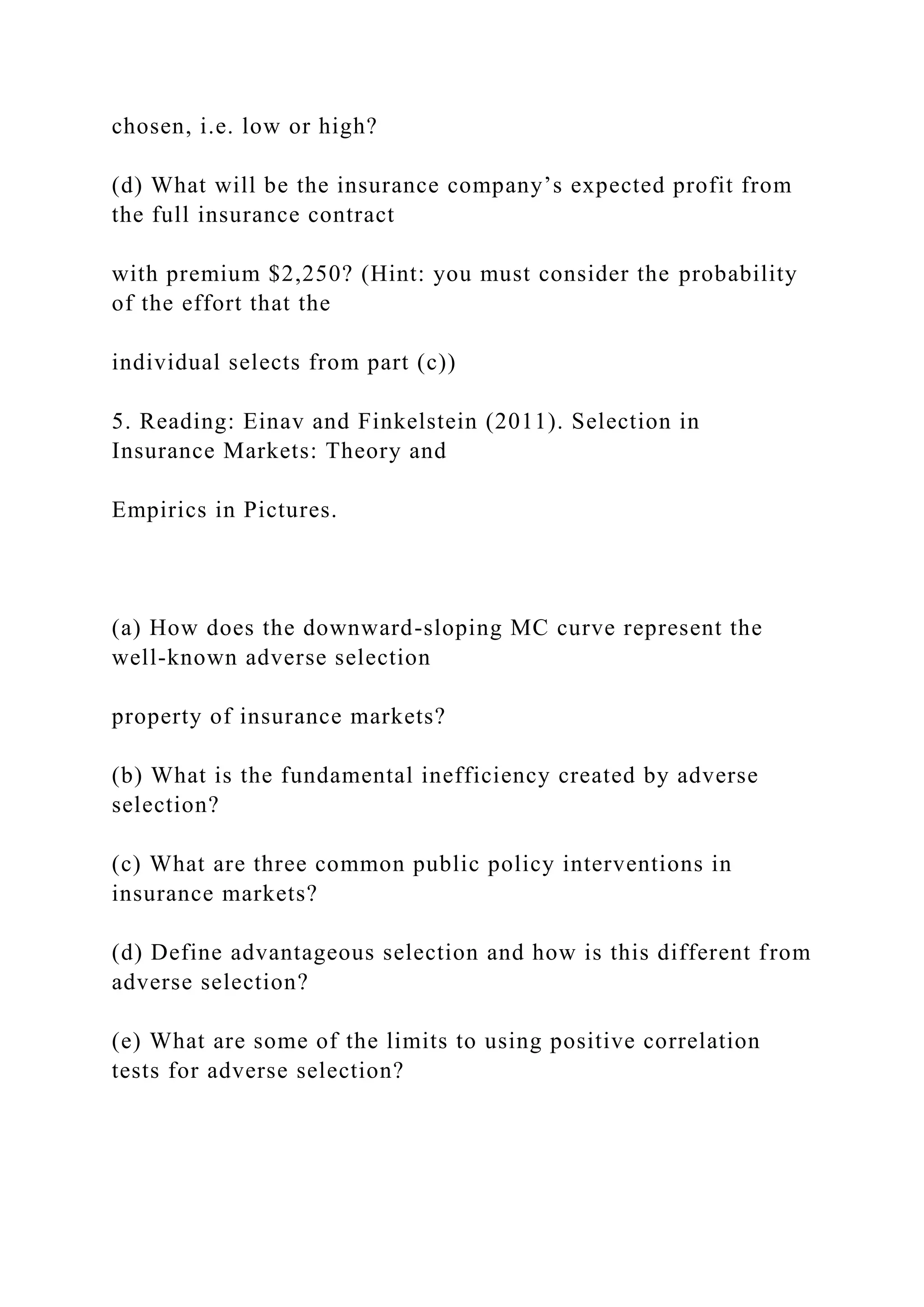

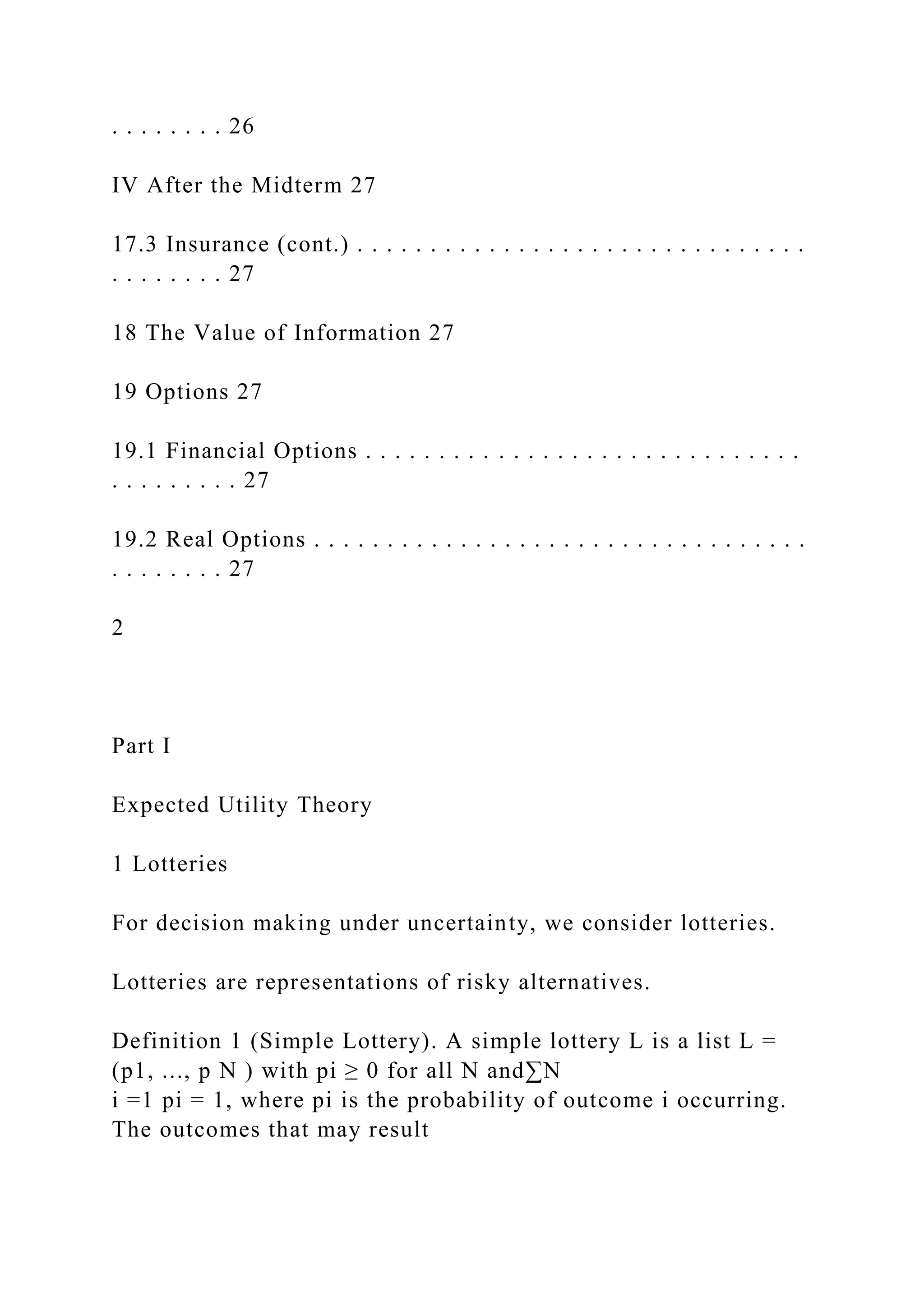

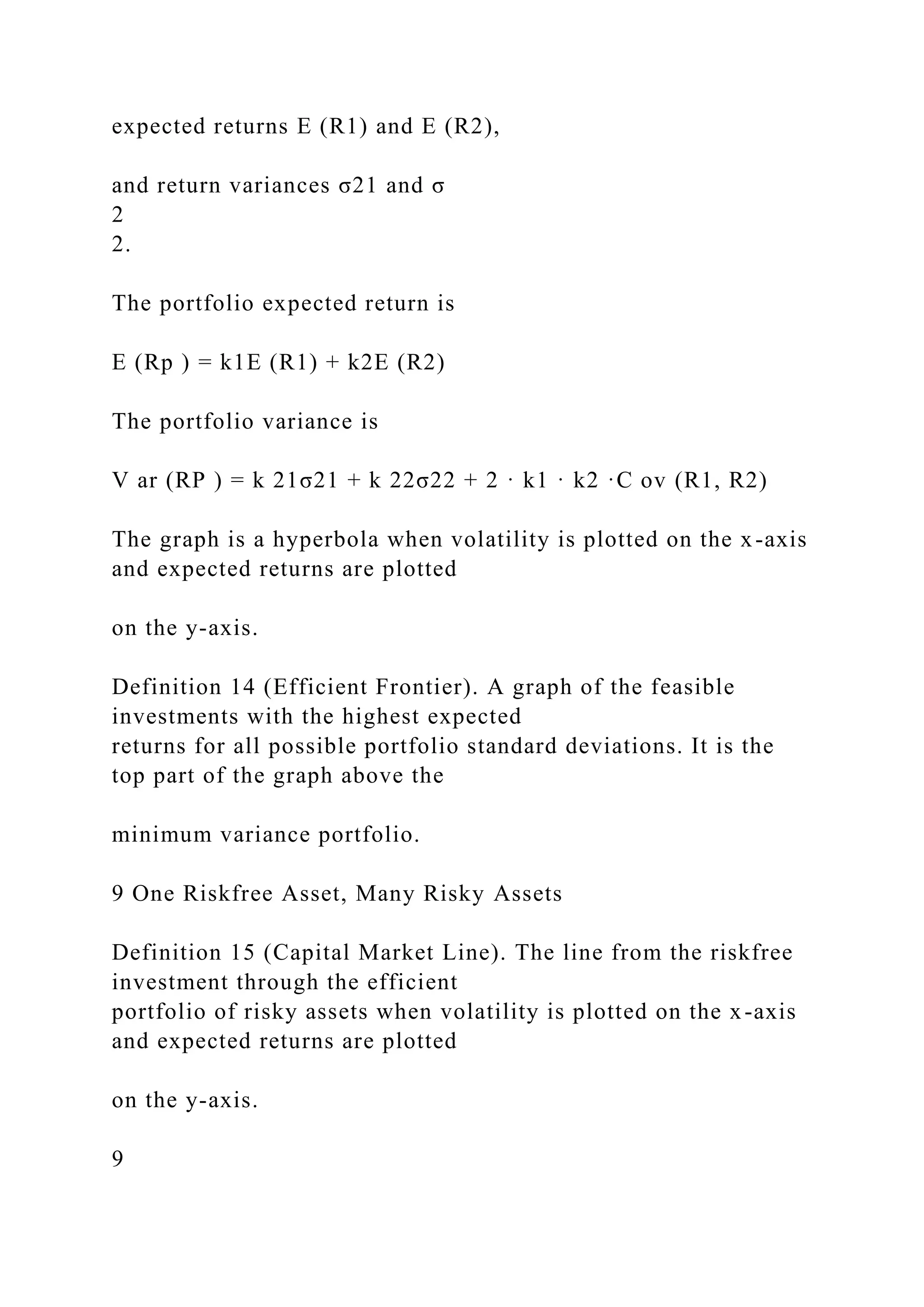

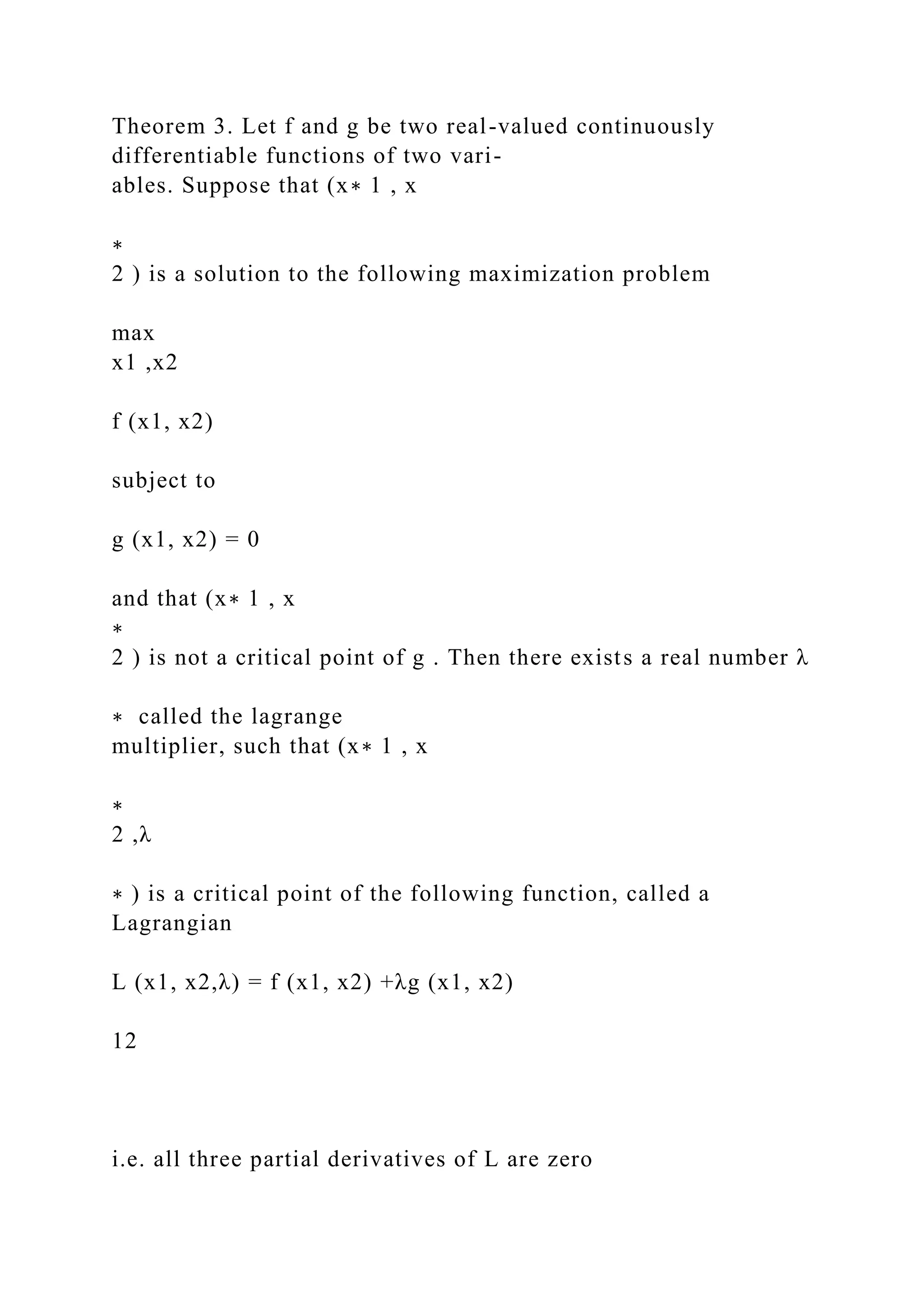

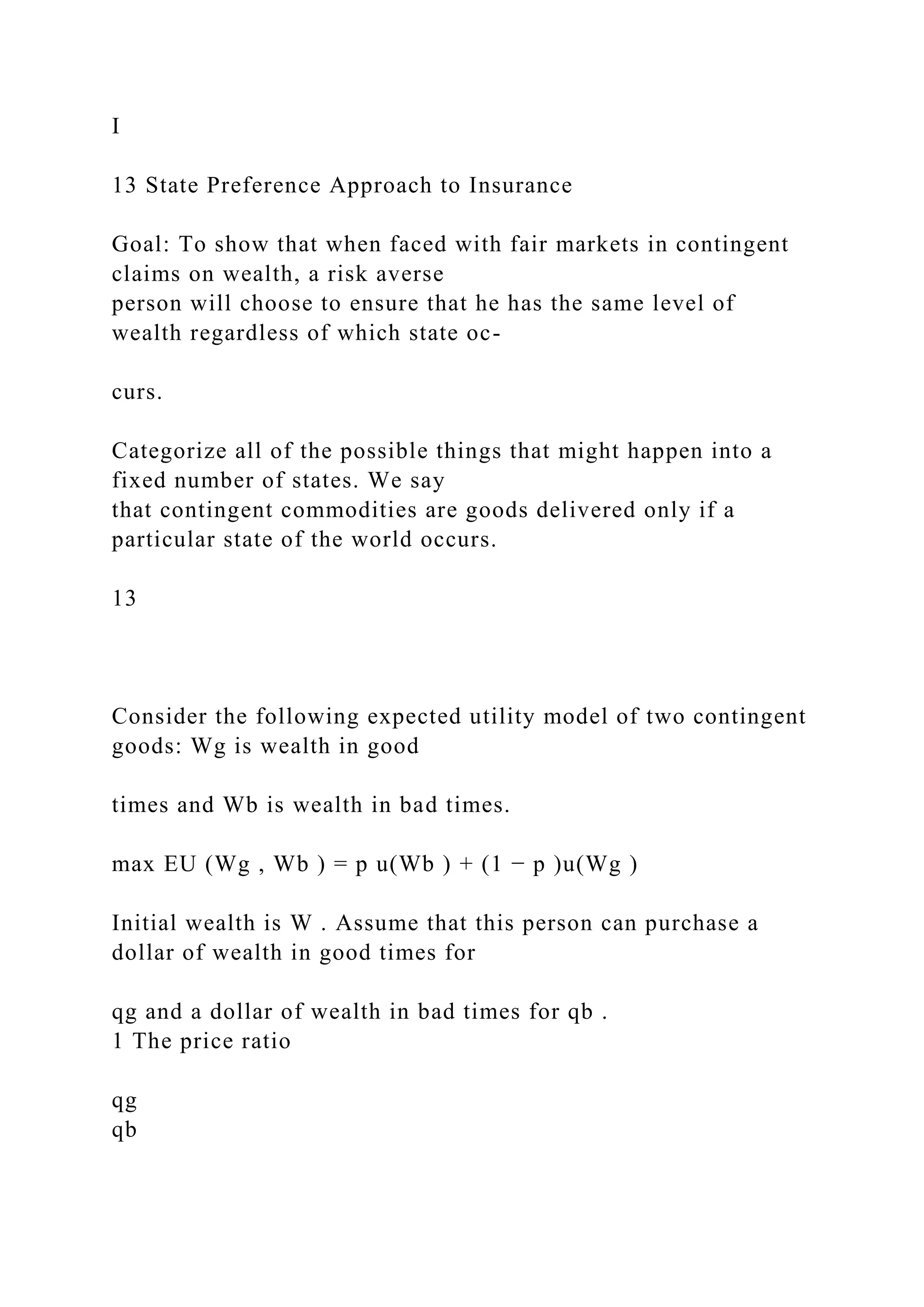

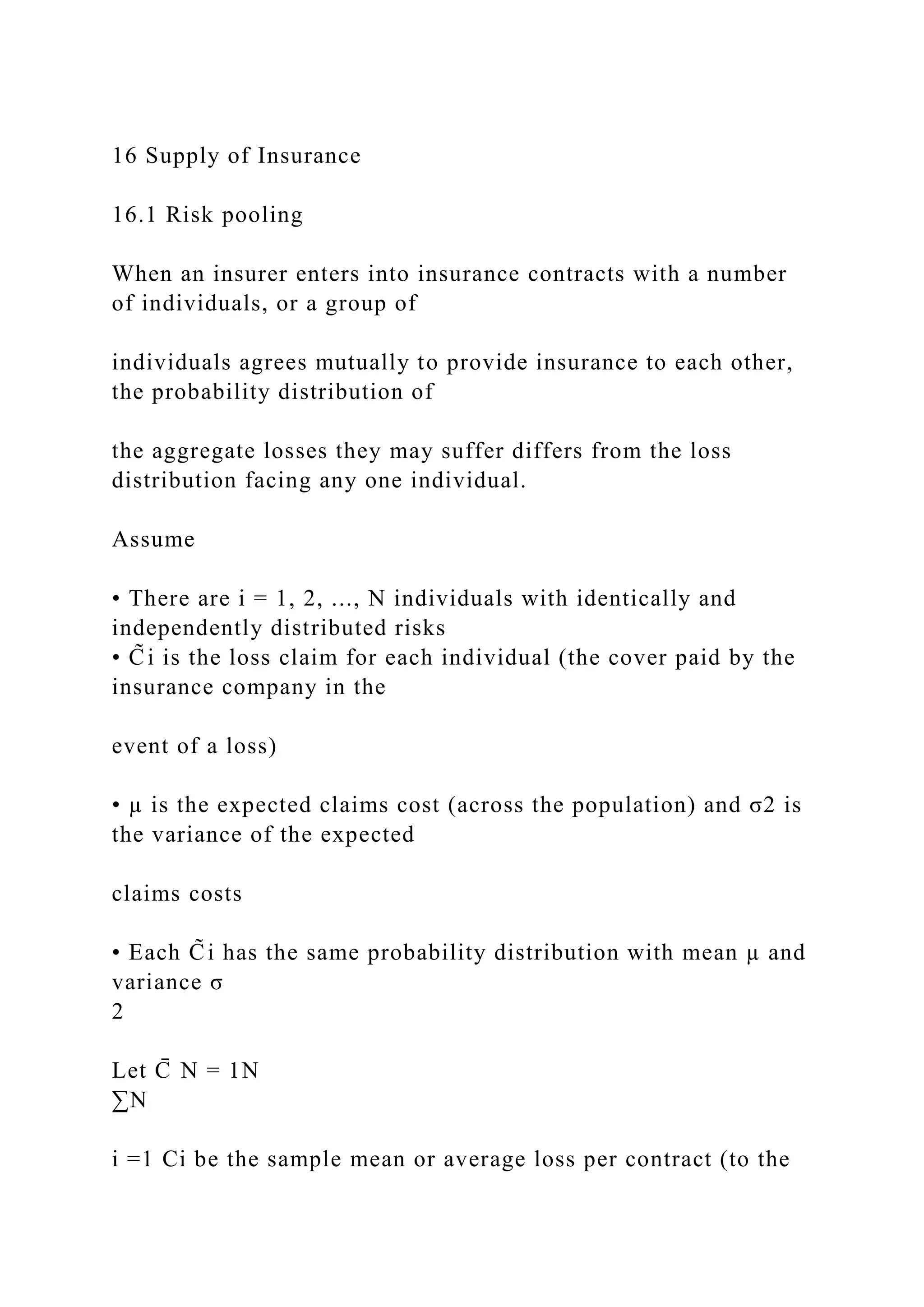

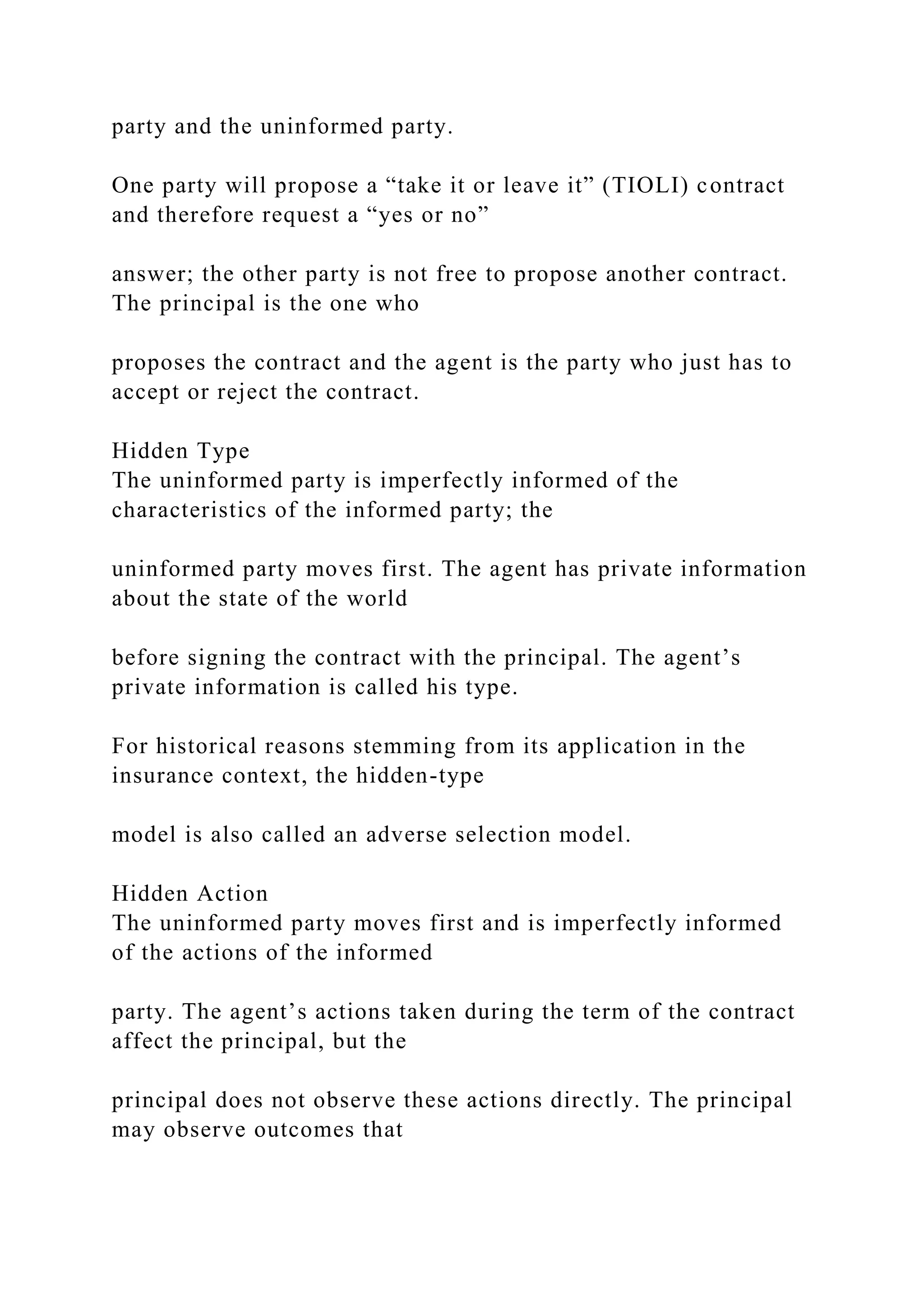

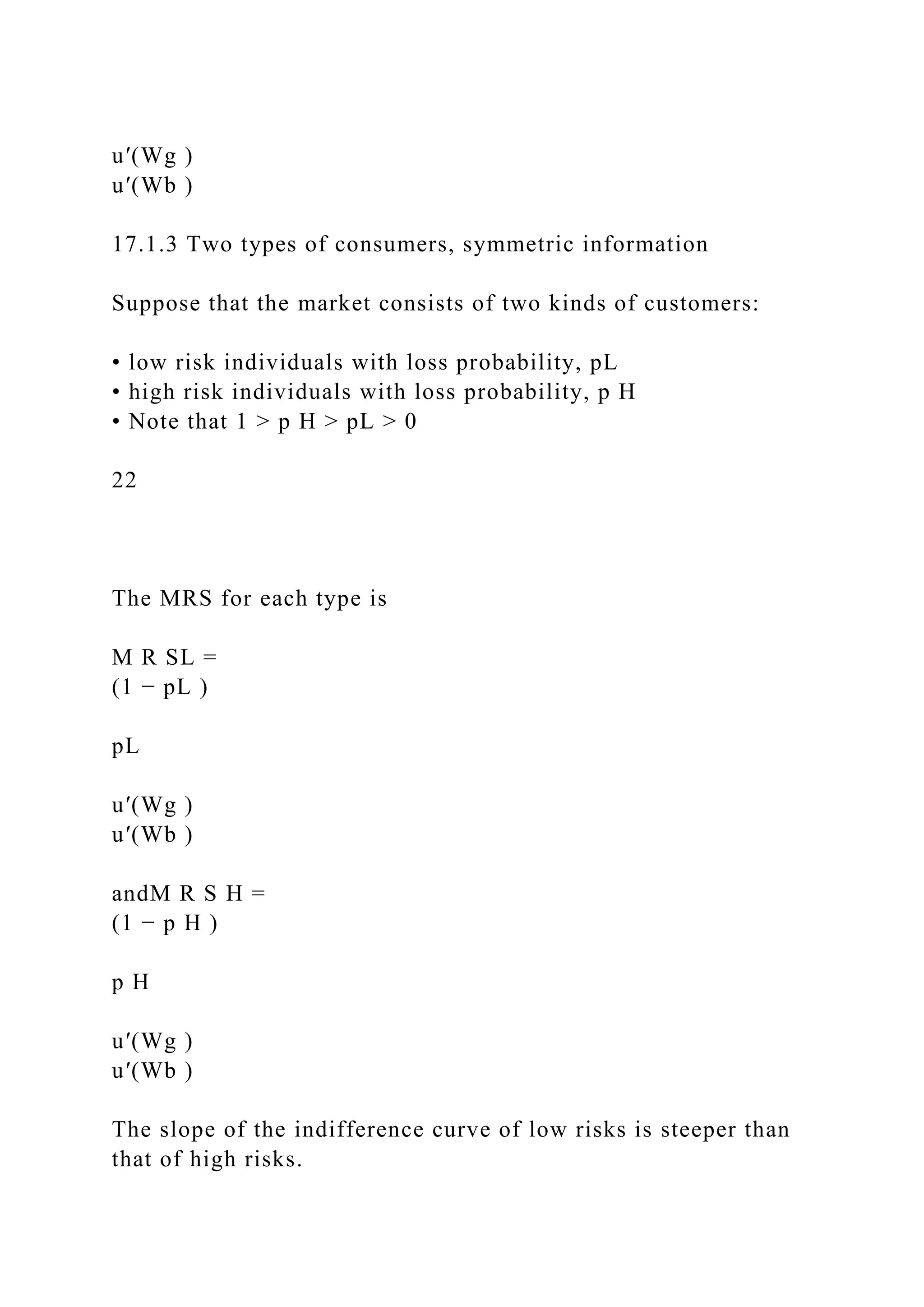

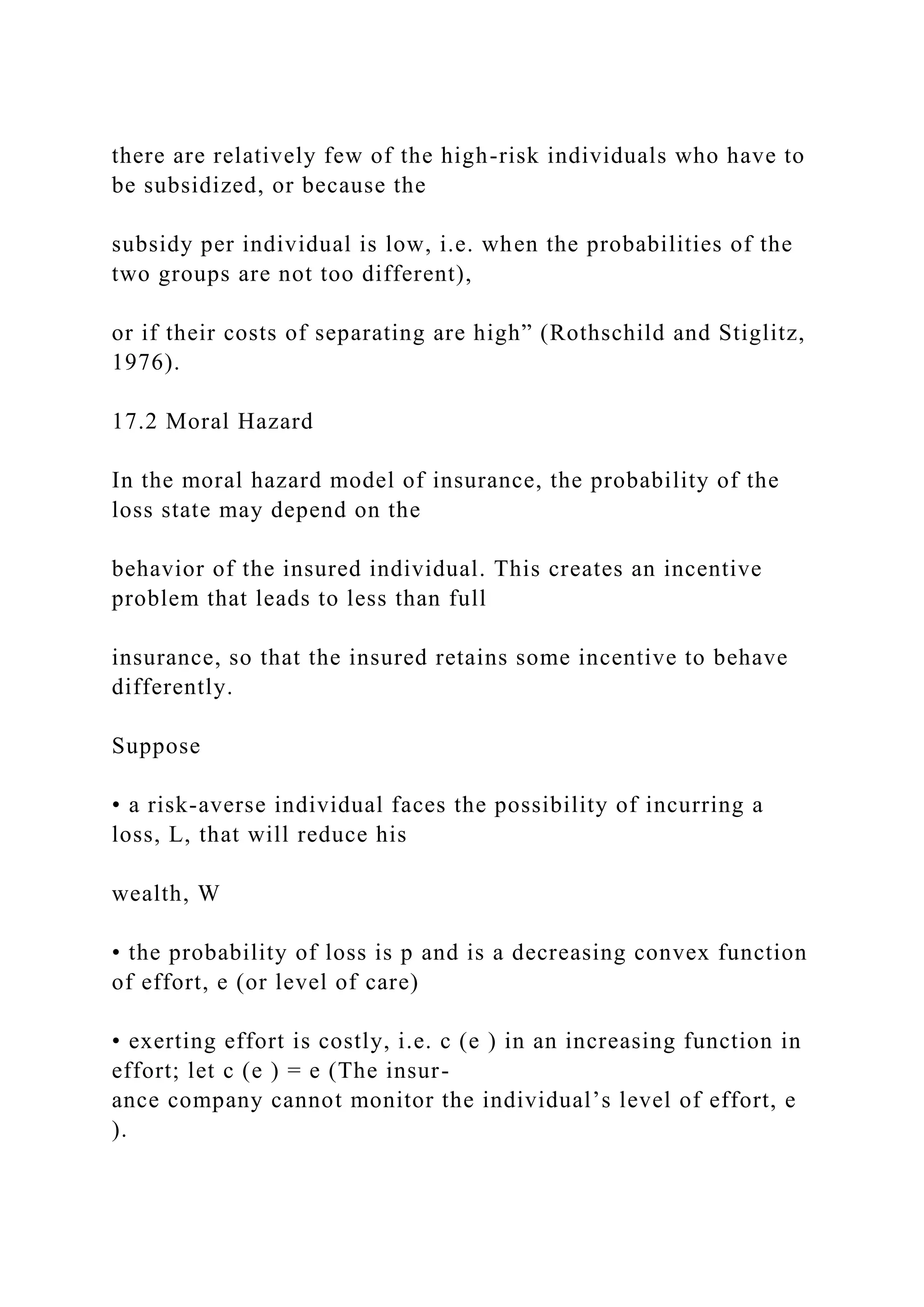

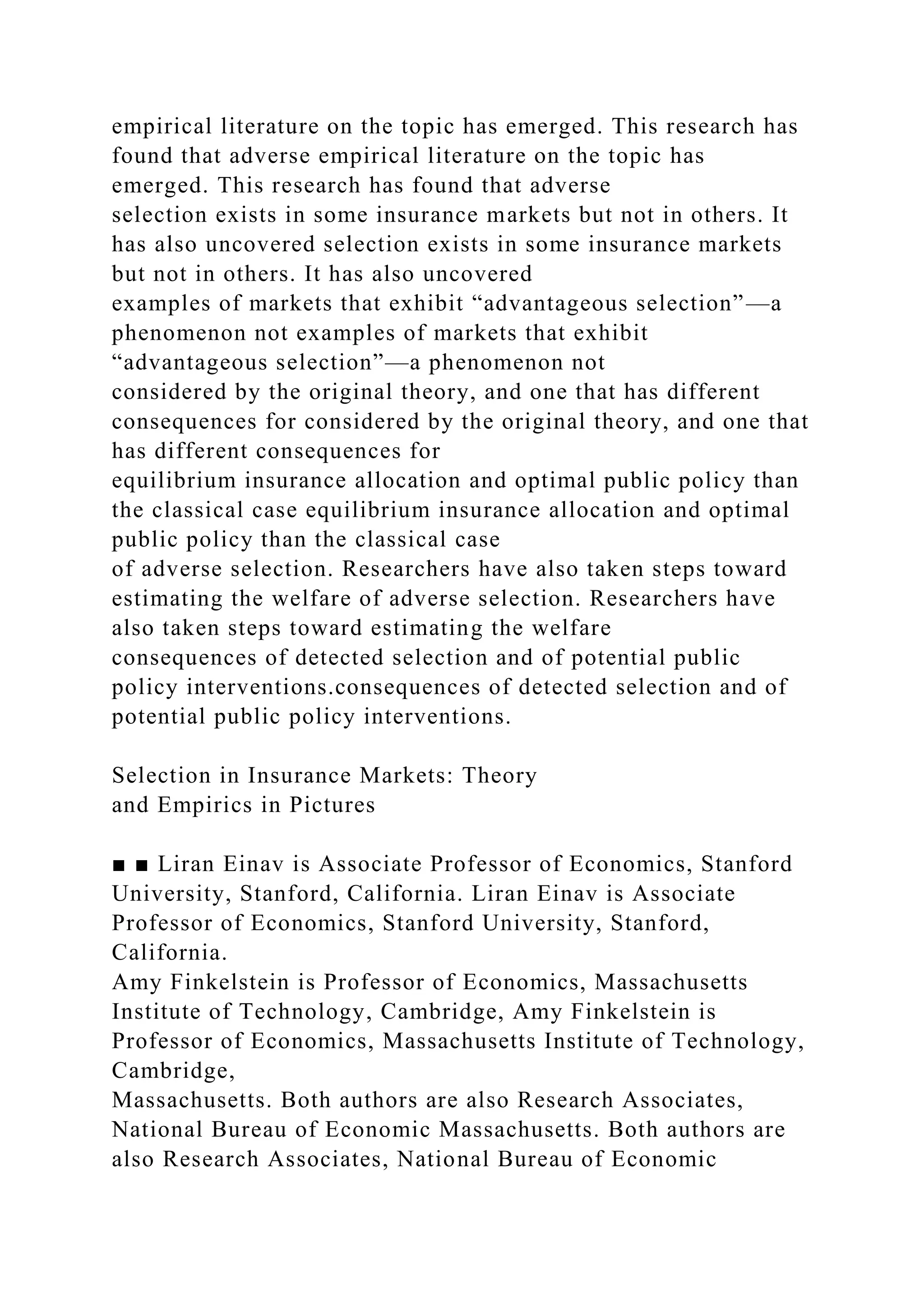

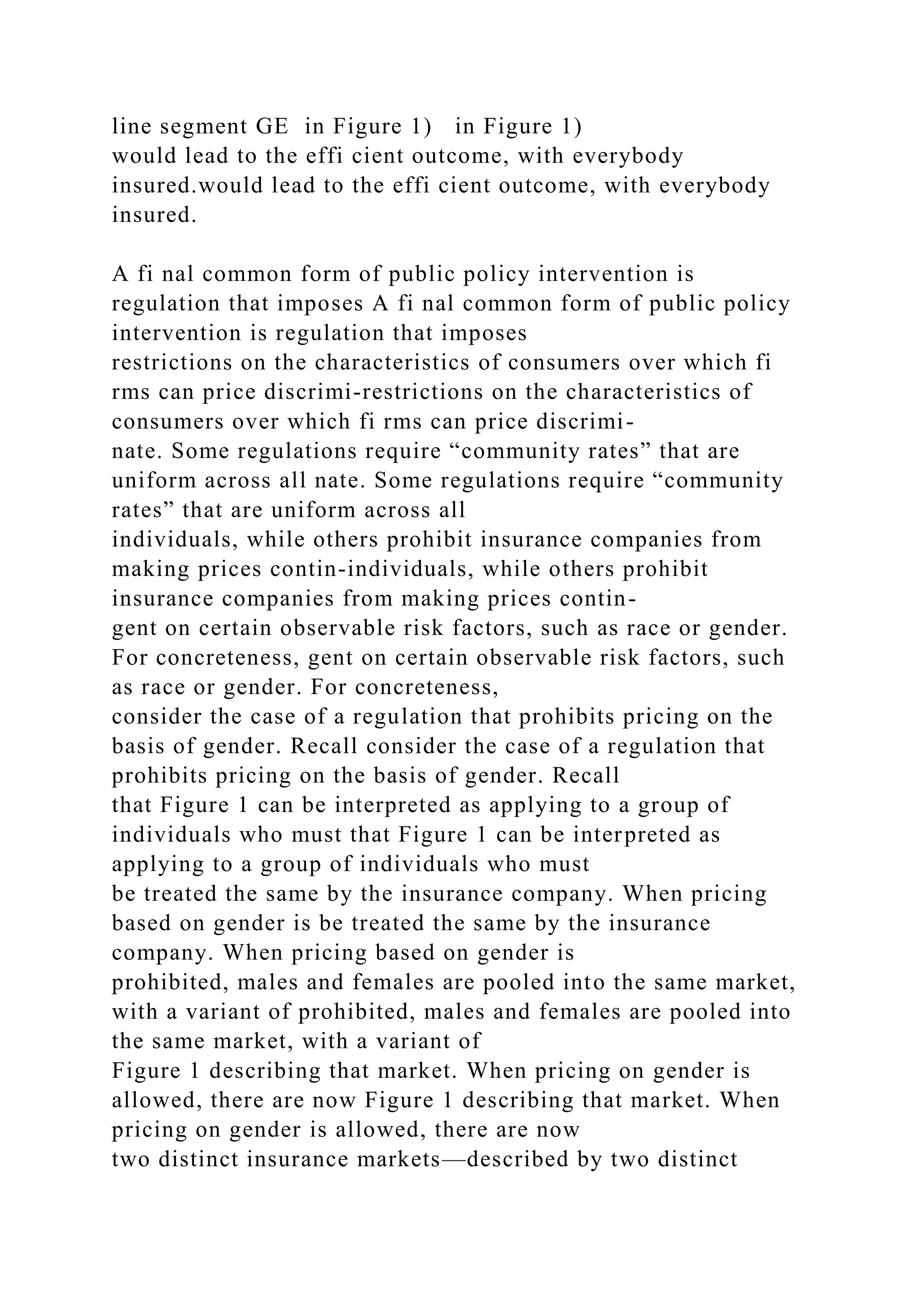

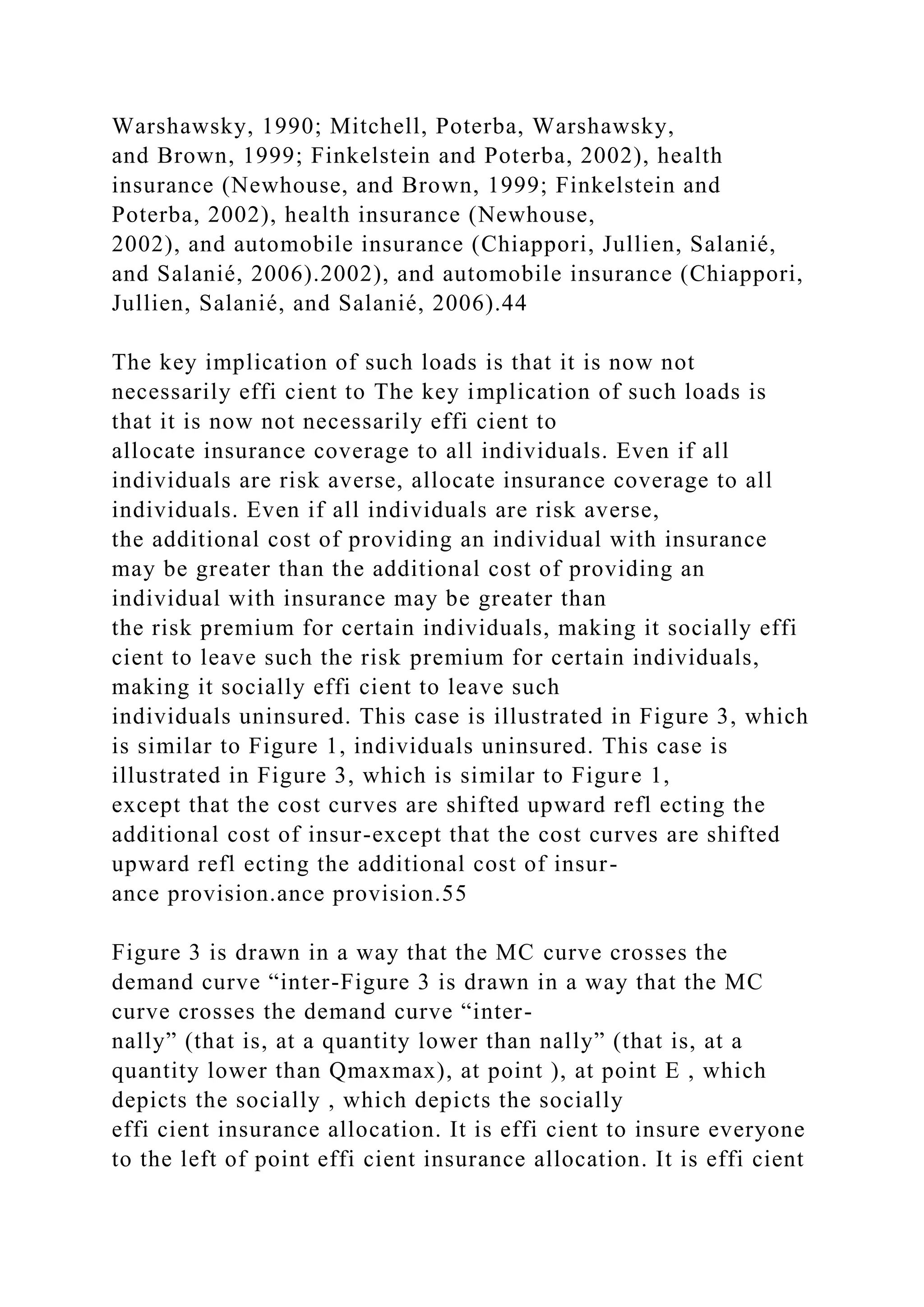

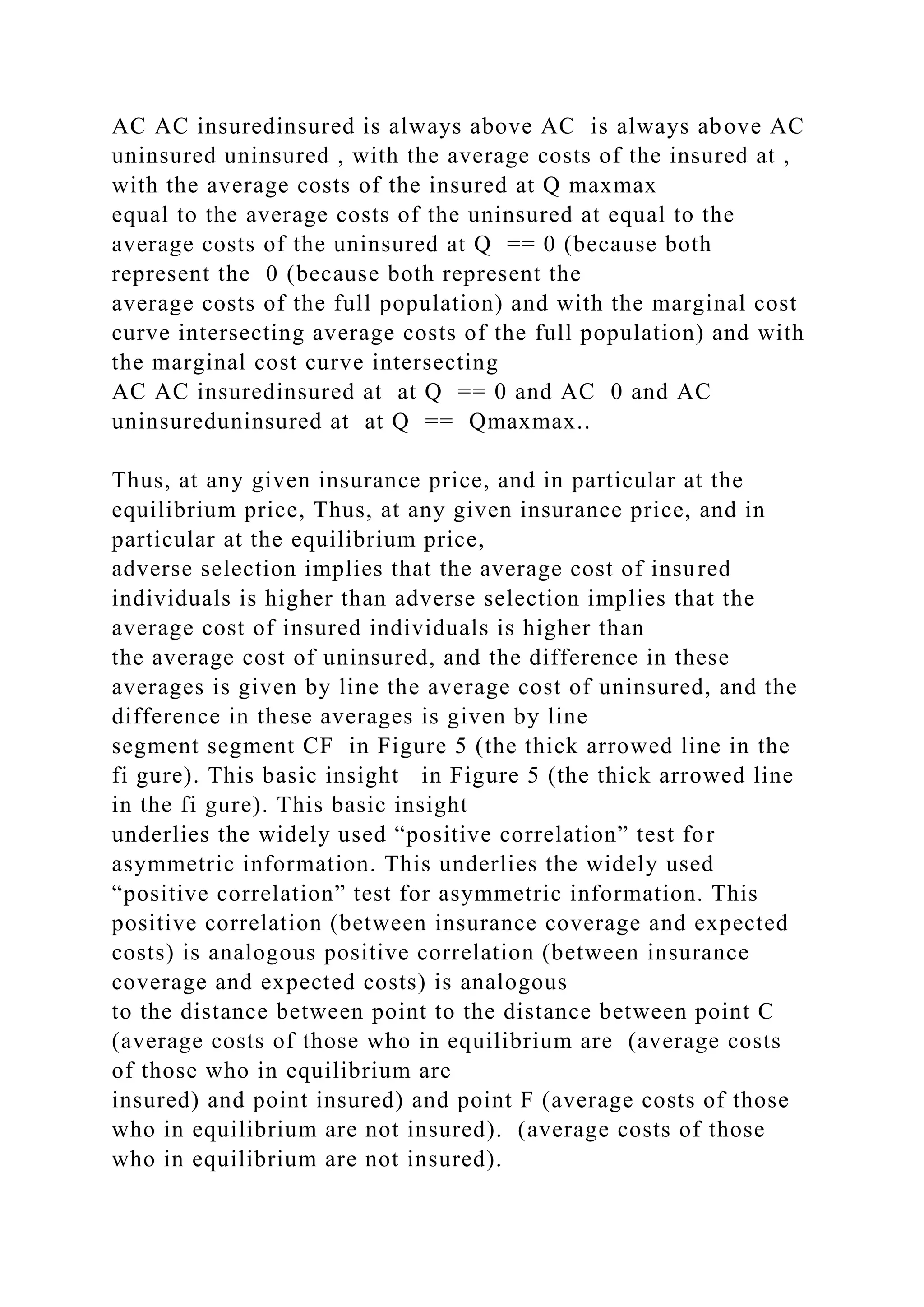

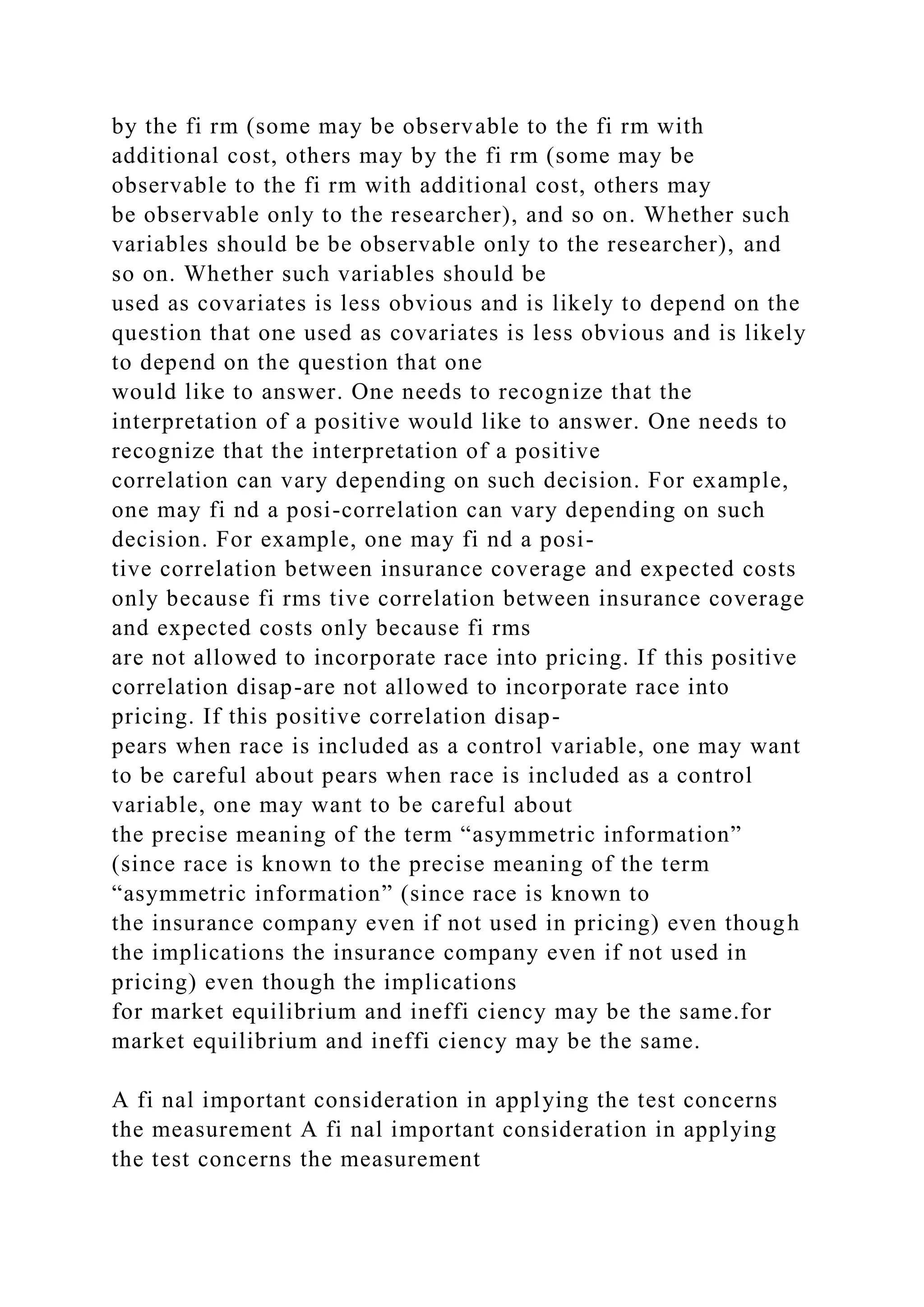

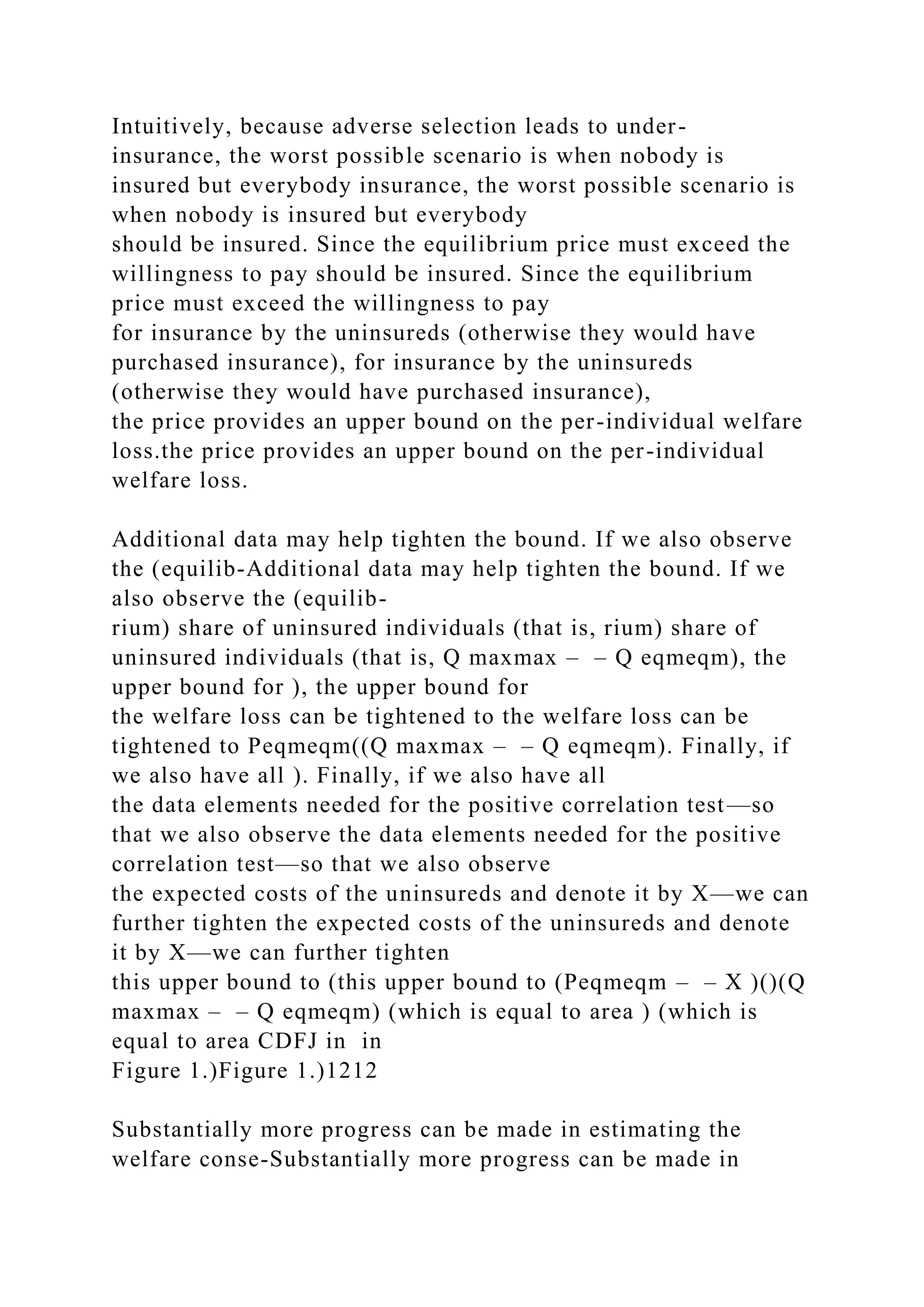

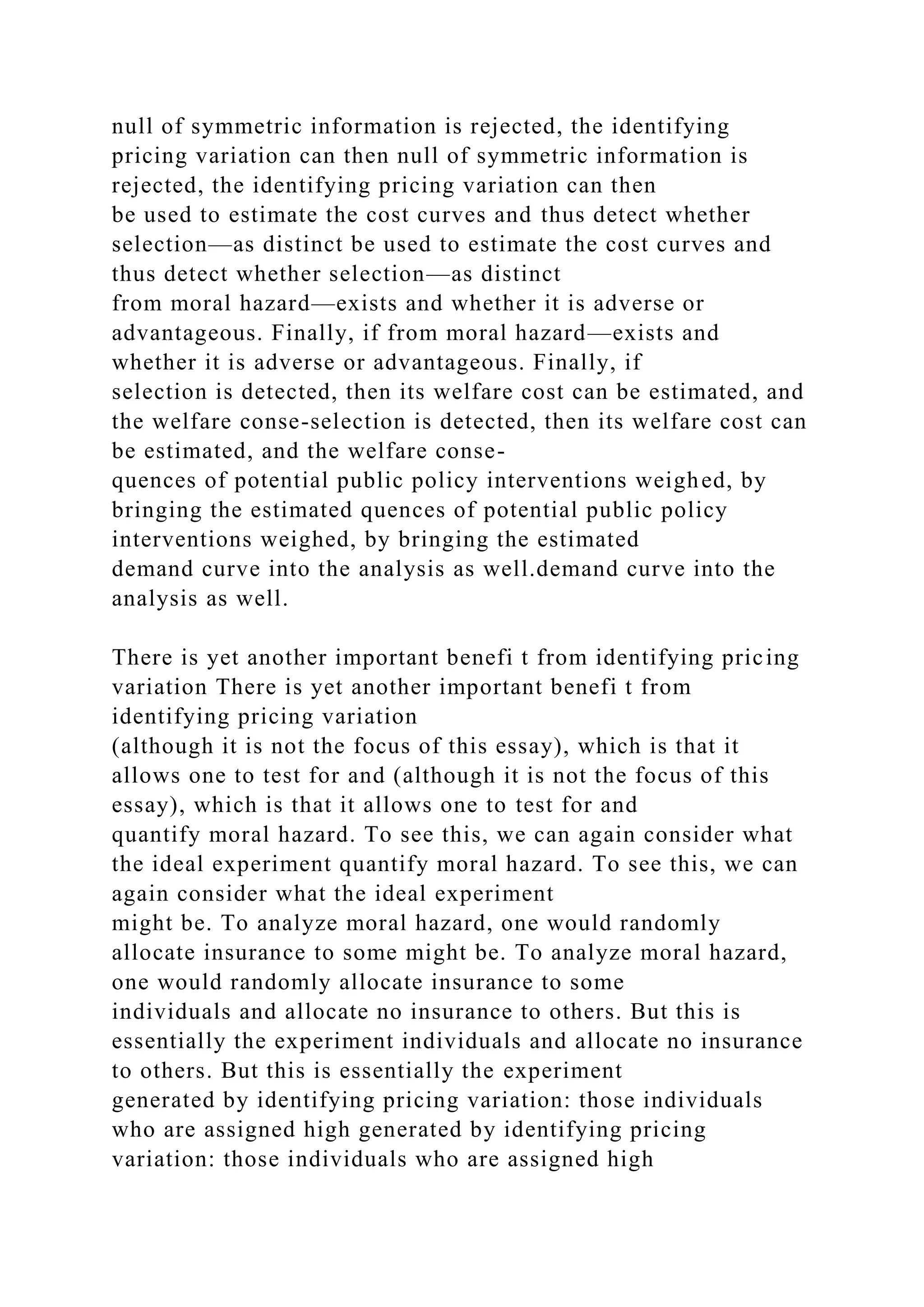

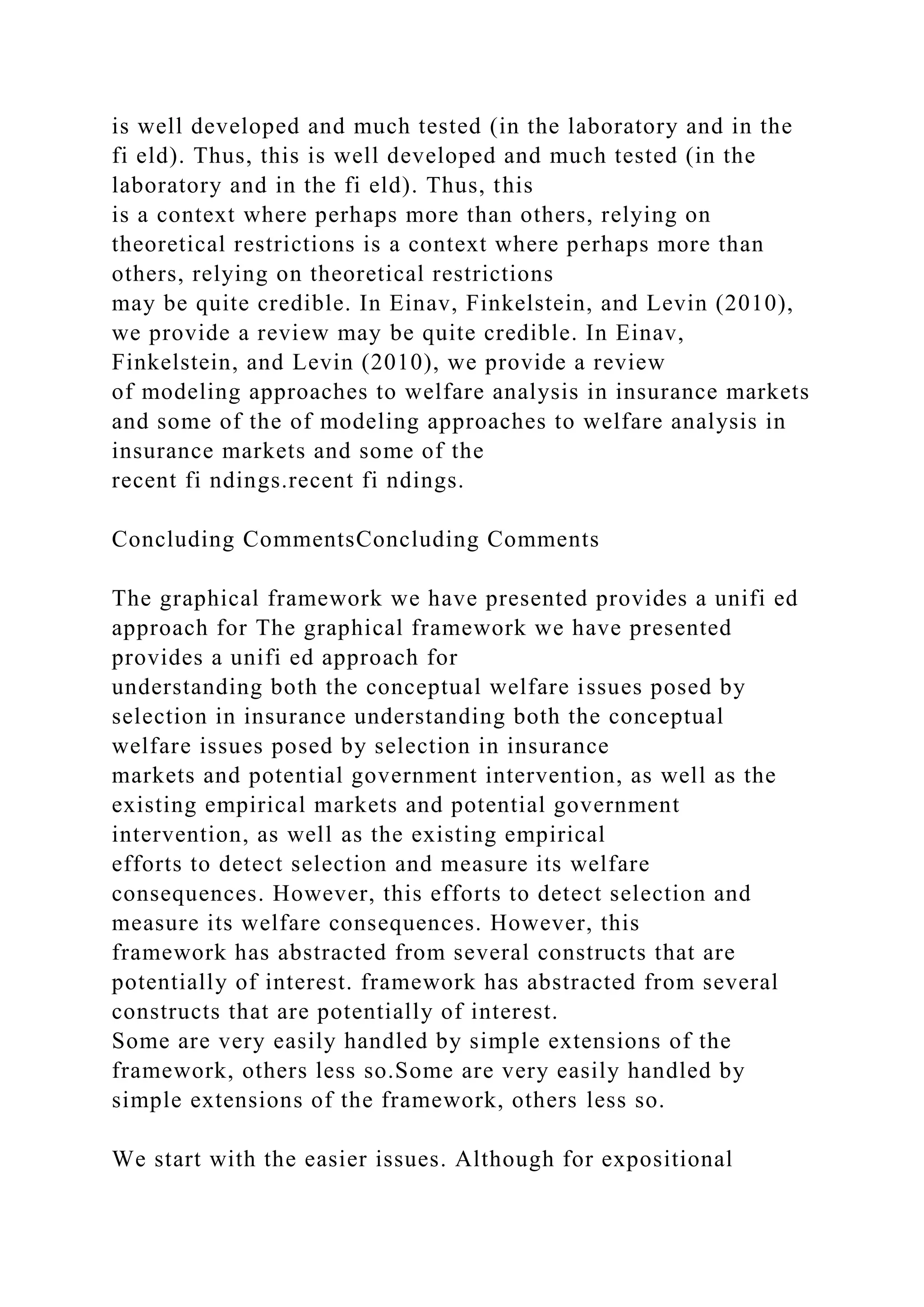

![C = αL, α ∈ [0, 1]

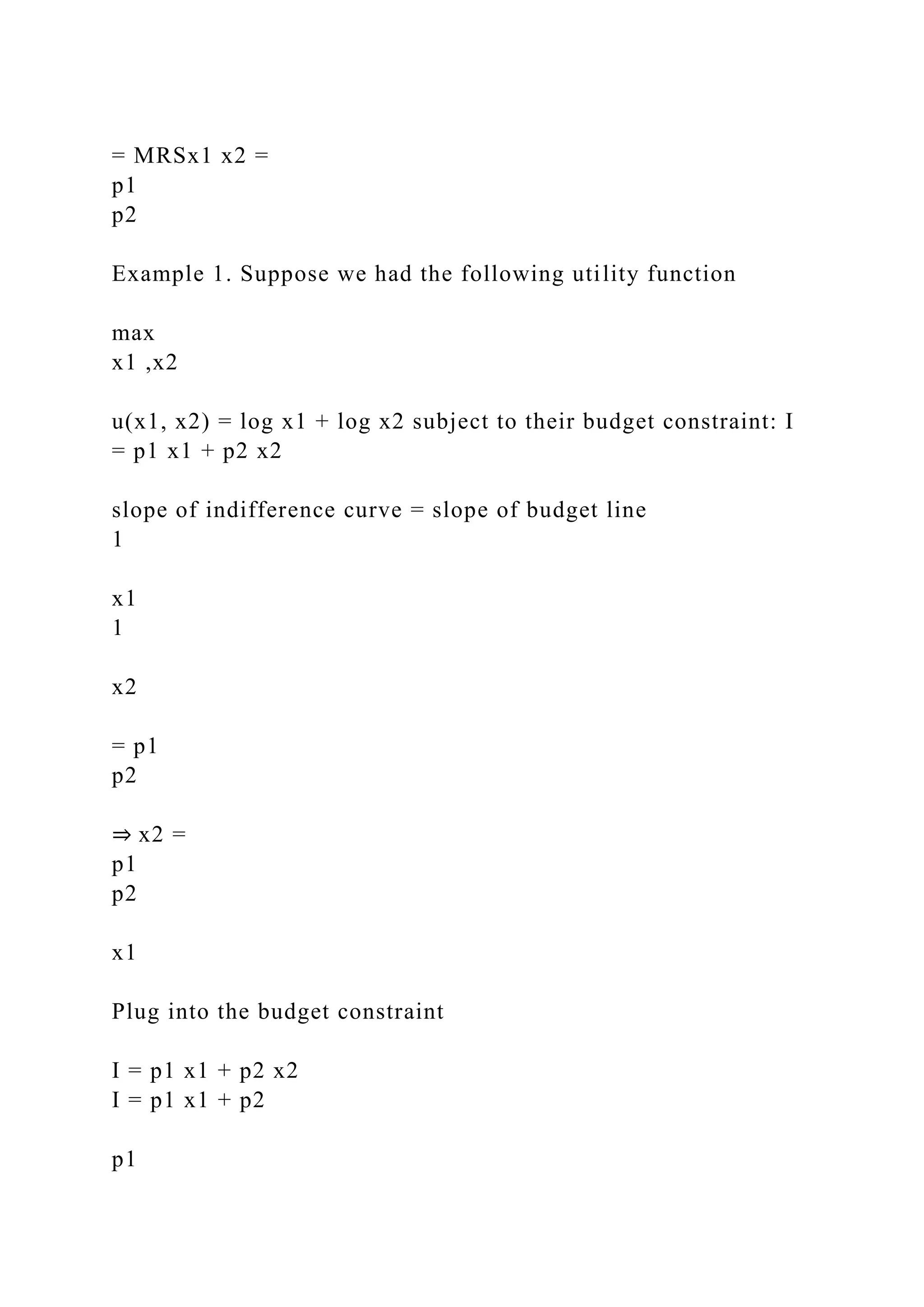

with α = 0 implying no insurance and α = 1 implying full cover.

Under a deductible we have

C =

{

0 for L ≤ D

L − D for L > D

where D denotes the deductible and D = 0 implies full cover.

Given the premium amount Q and wealth W in the absence of

loss, the buyer’s state-contingent

wealth in the case of proportional coinsurance is

Wα = W − L −Q +C = W − (1 −α)L −Q

17

and in the case of a deductible is

WD = W − L −Q +C = W − L −Q + max(0, L − D )

For losses above the deductible, her wealth becomes certain,

and equal to

ŴD = W − L −Q + (L − D ) = W −Q − D

A straight deductible insurance policy efficiently concentrates

the effort of indemnification on

only the largest losses.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/econ417economicsofuncertaintycontentsiexpectedu-221031050641-9b4fc79f/75/ECON-417-Economics-of-UncertaintyContentsI-Expected-U-docx-37-2048.jpg)

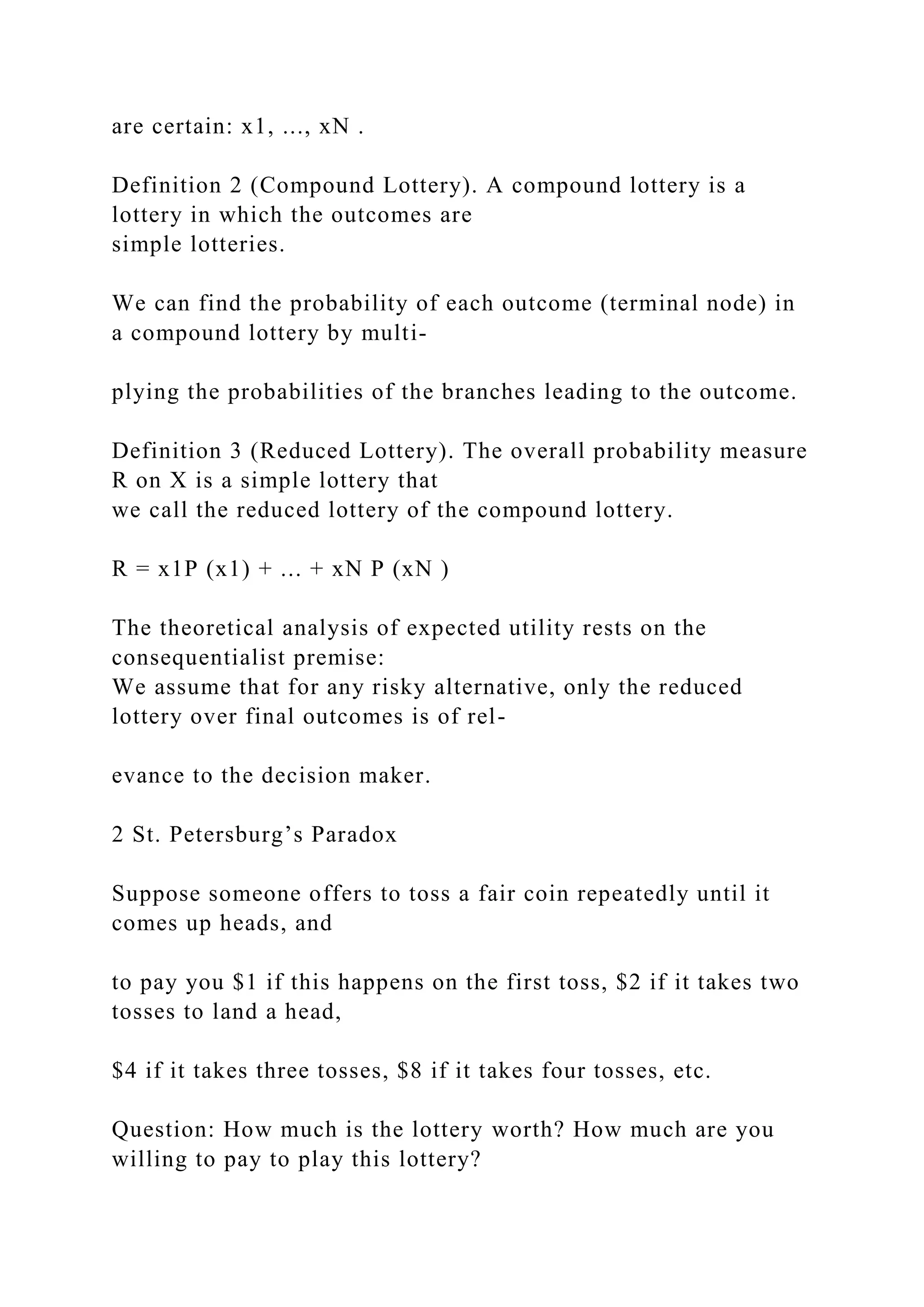

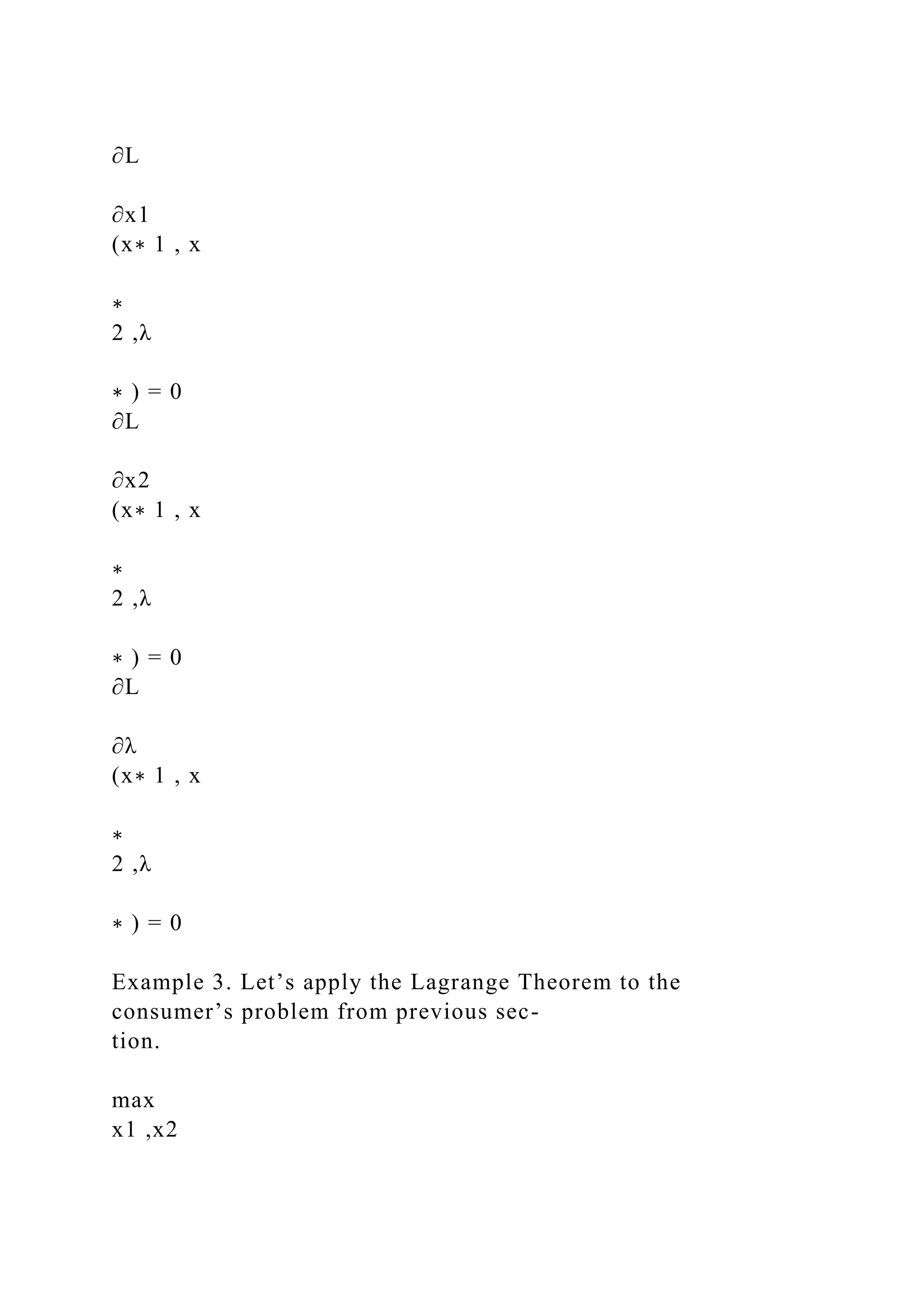

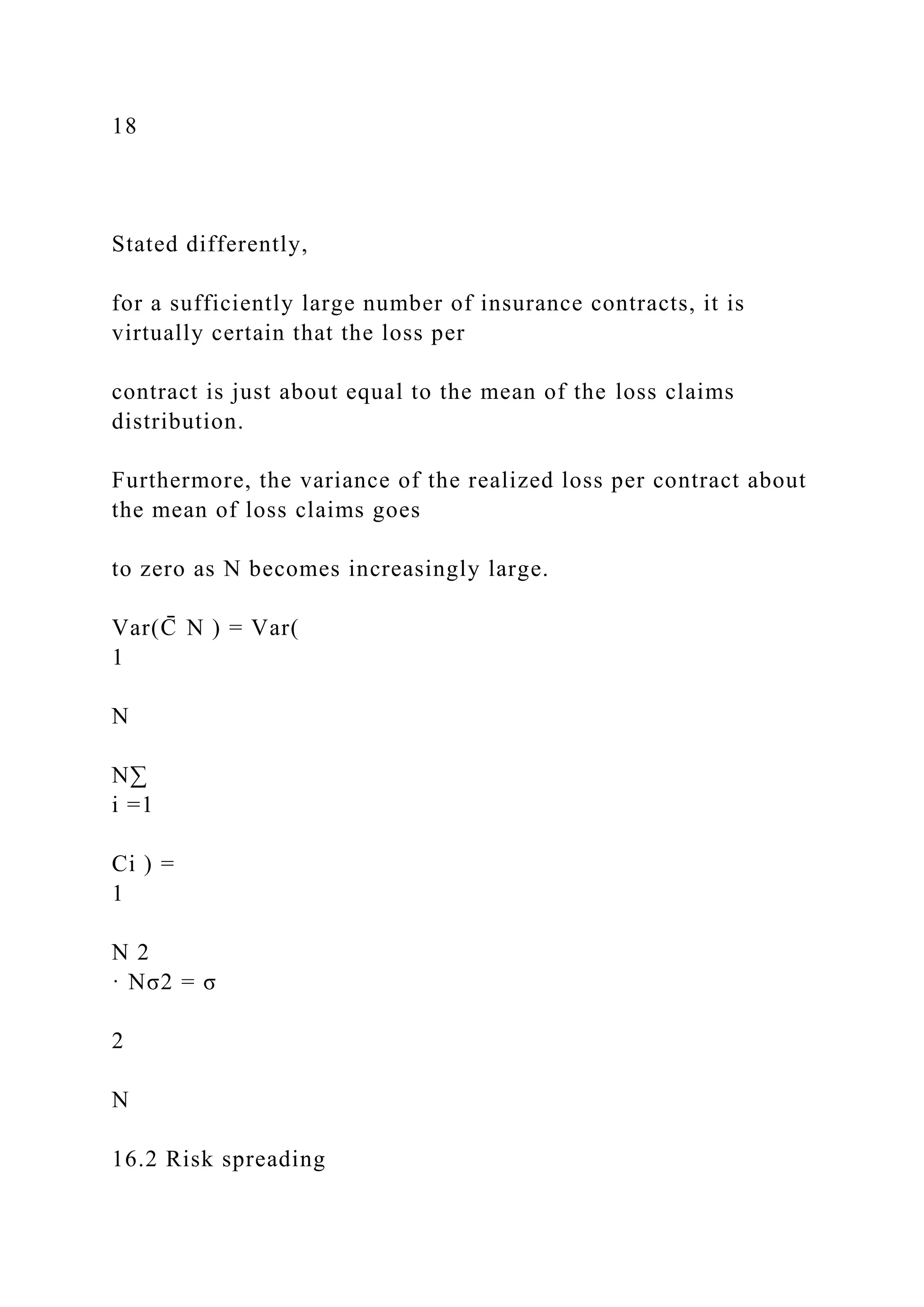

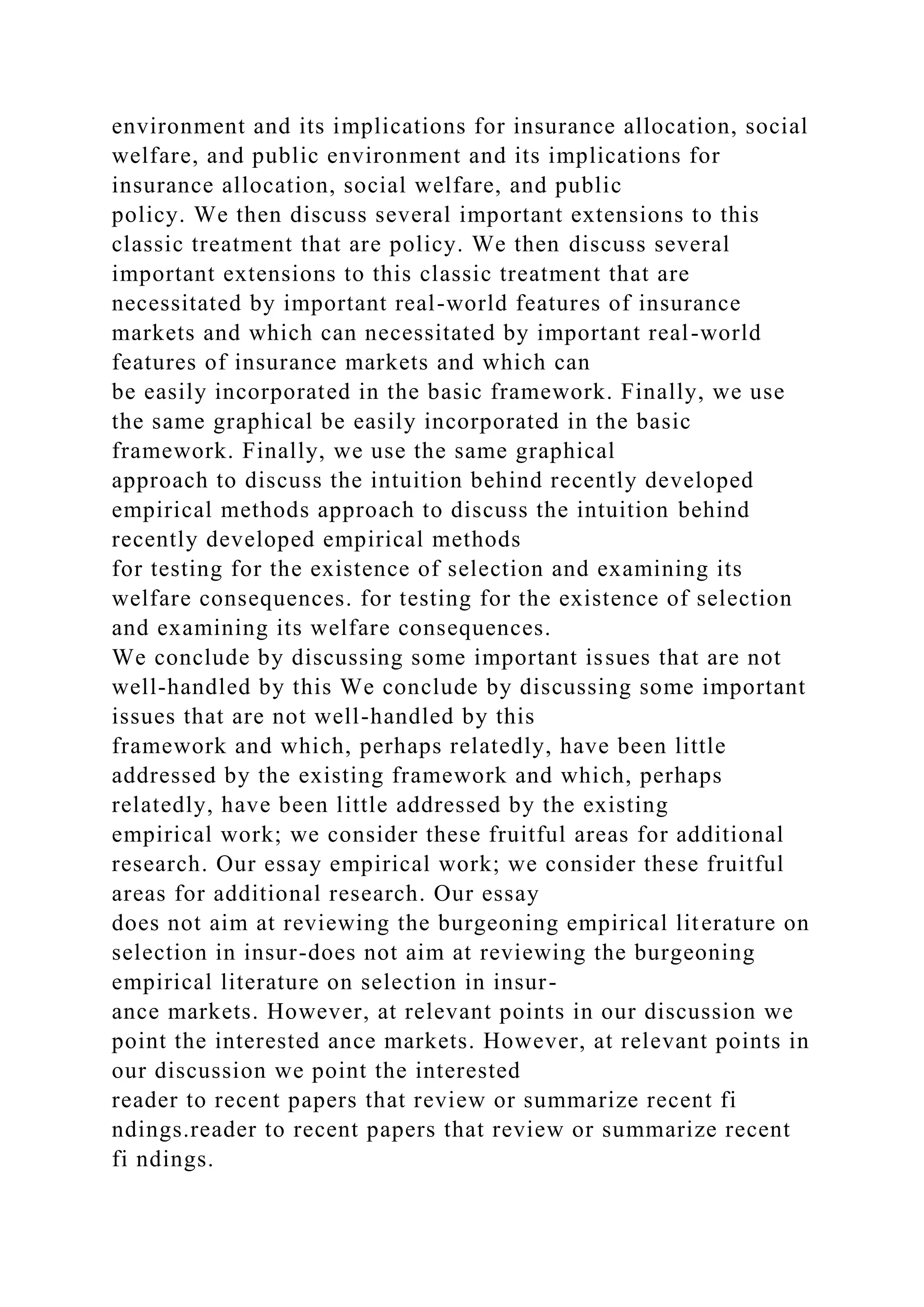

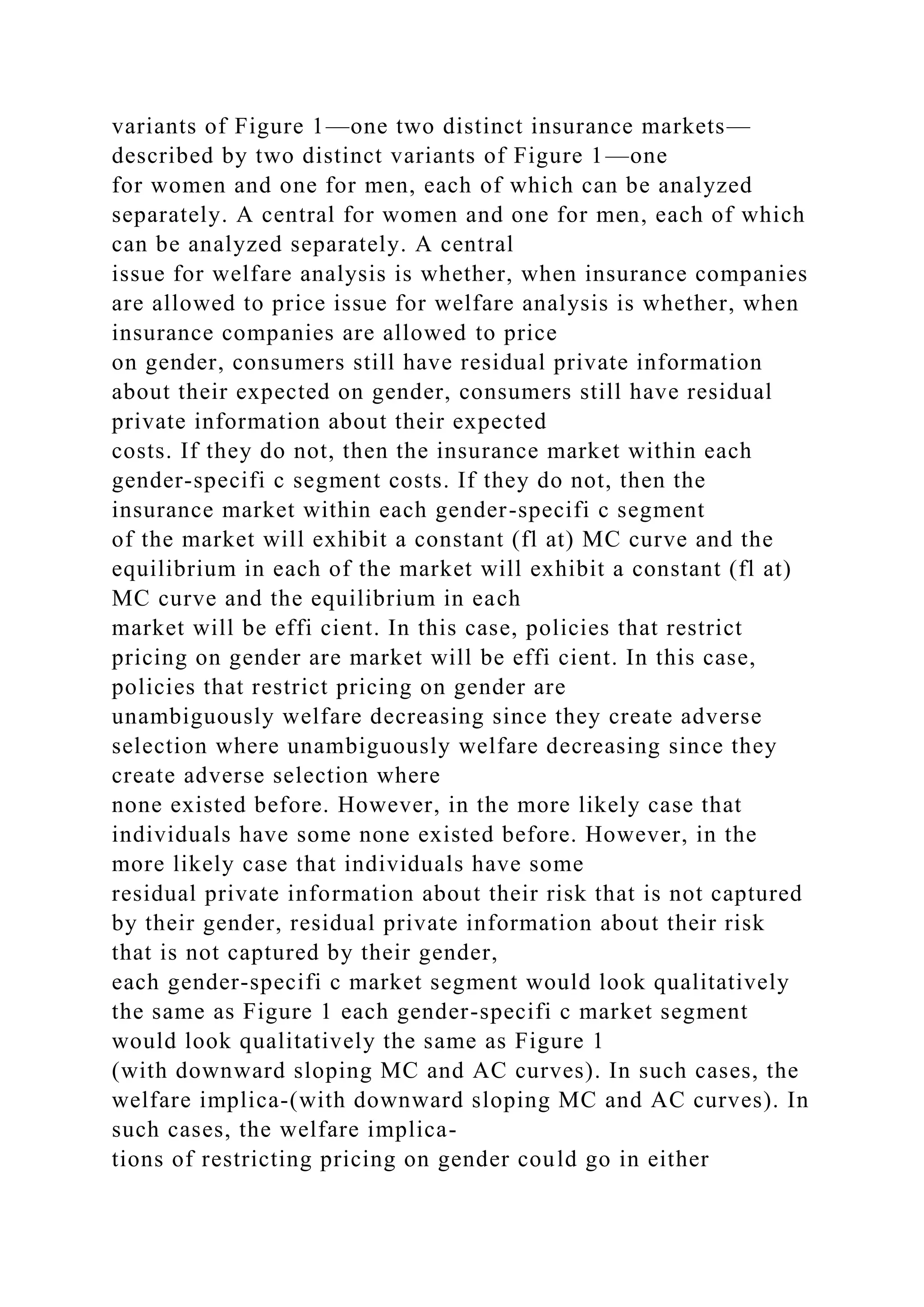

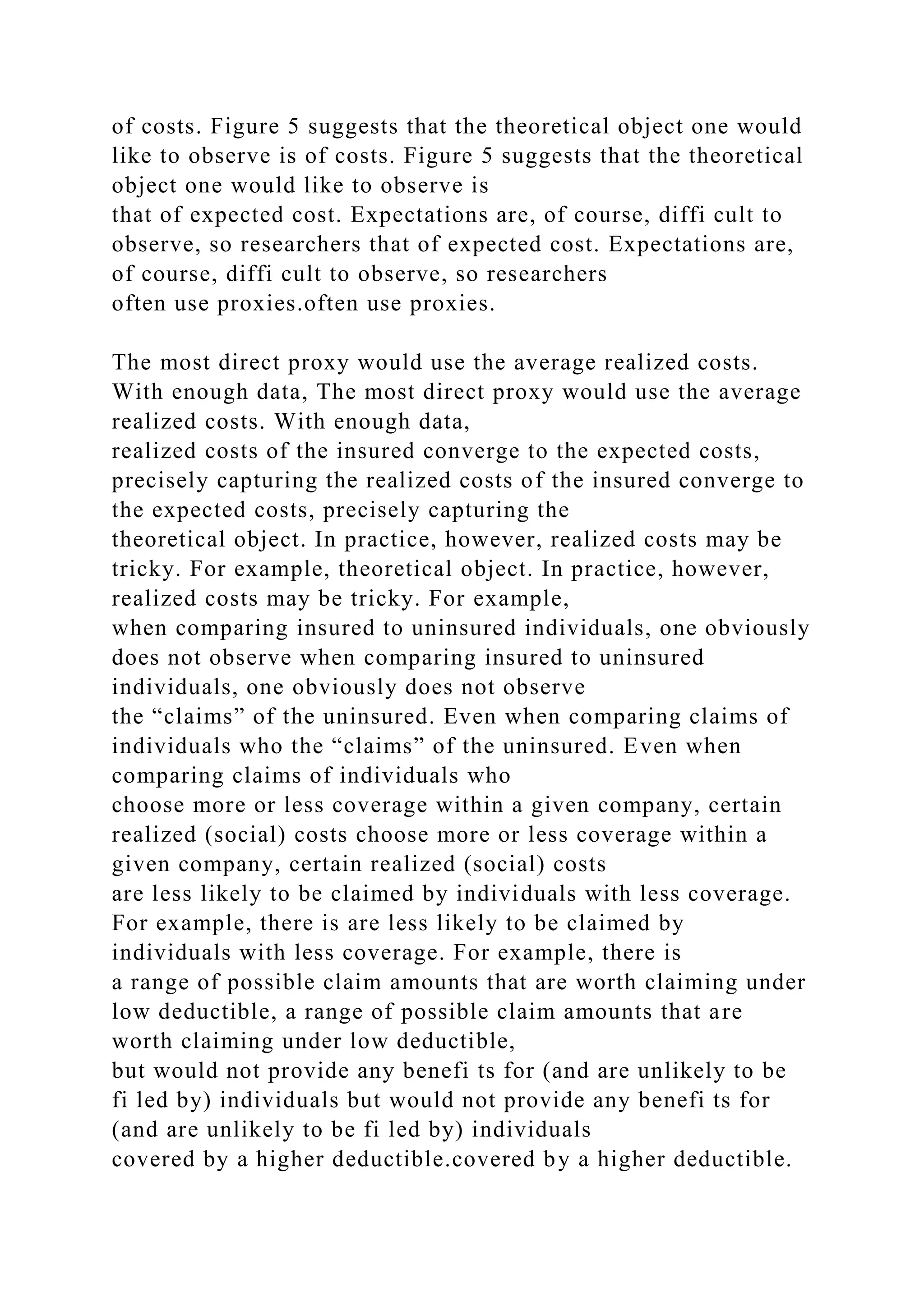

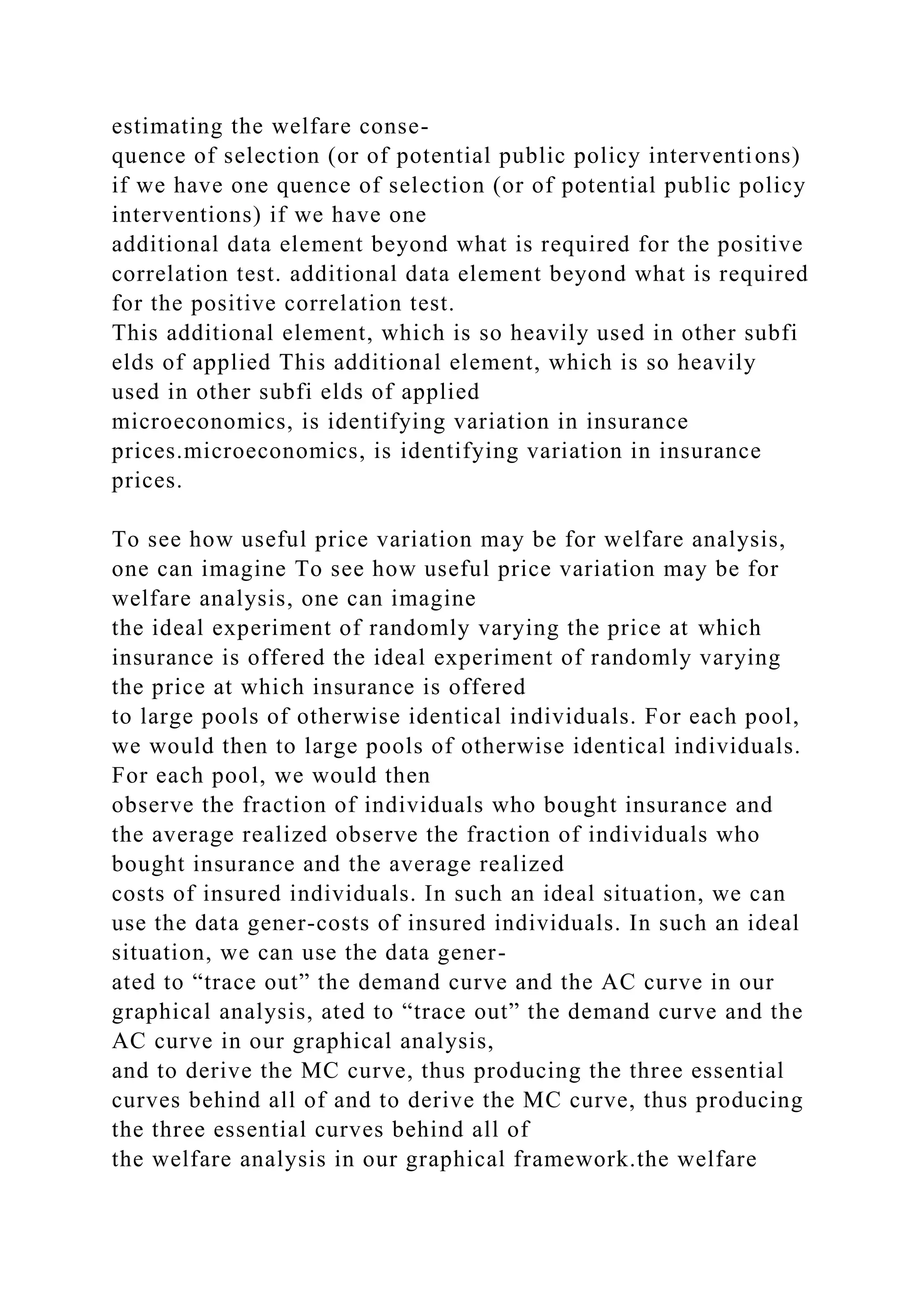

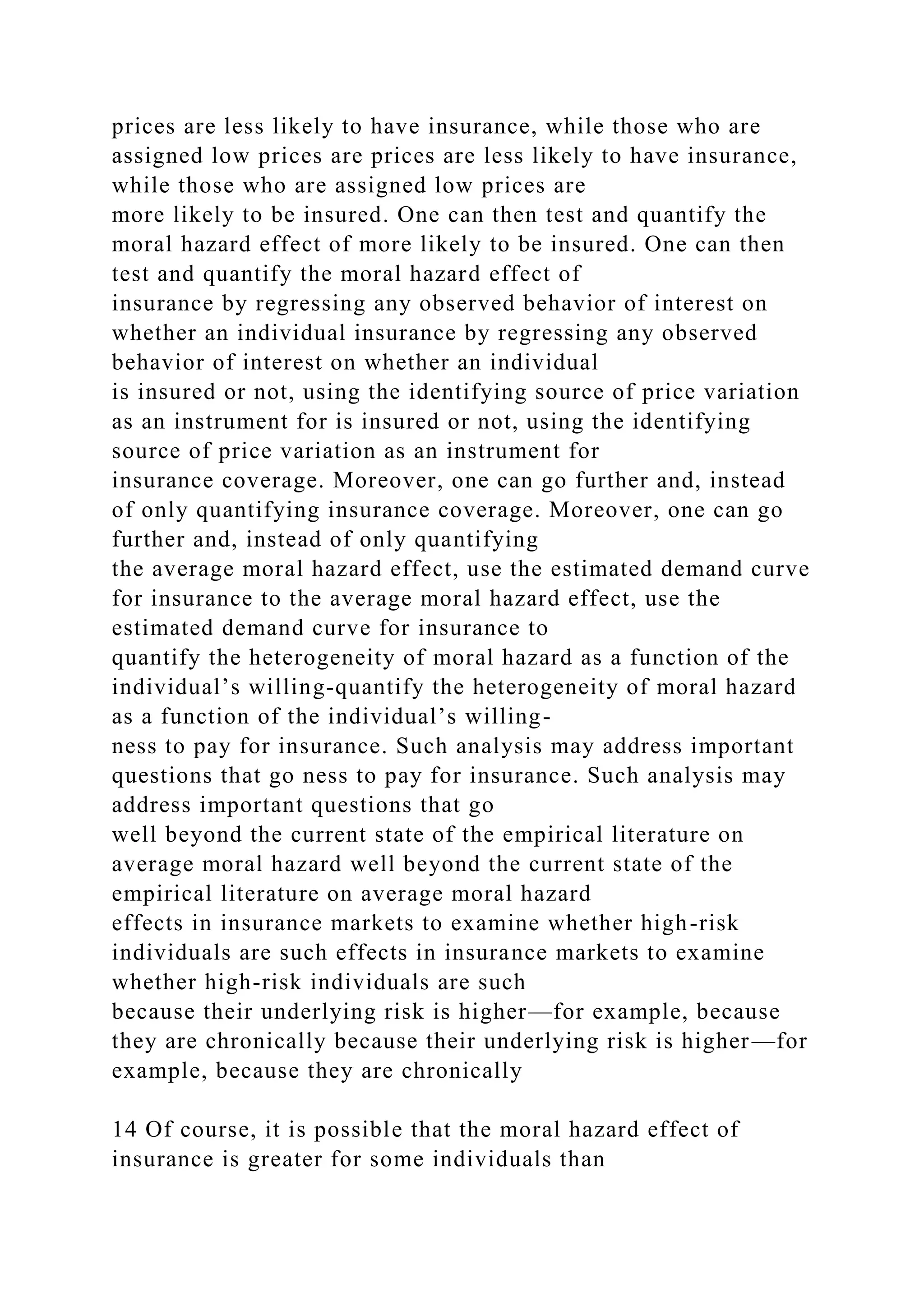

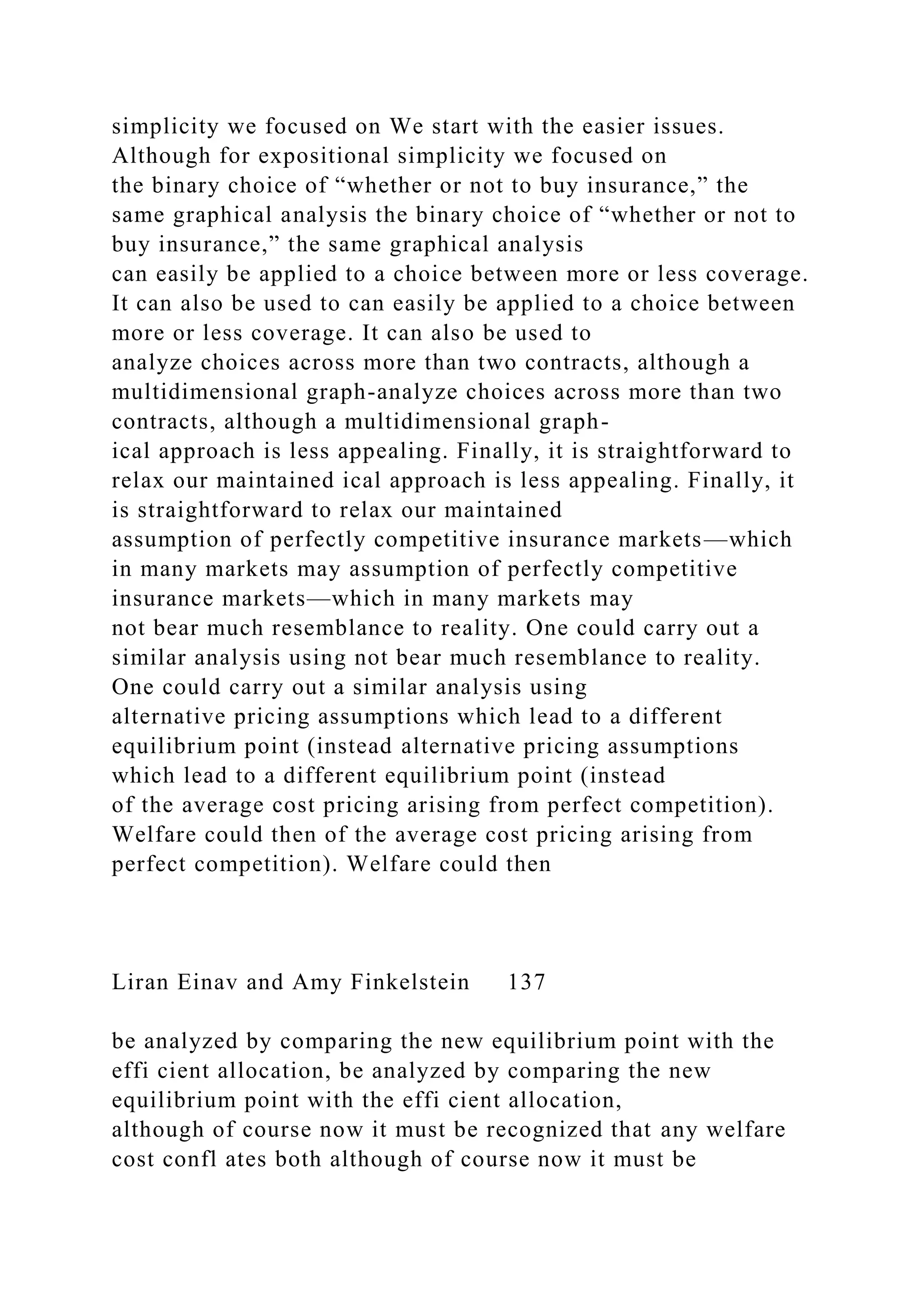

![insurance com-

pany).2

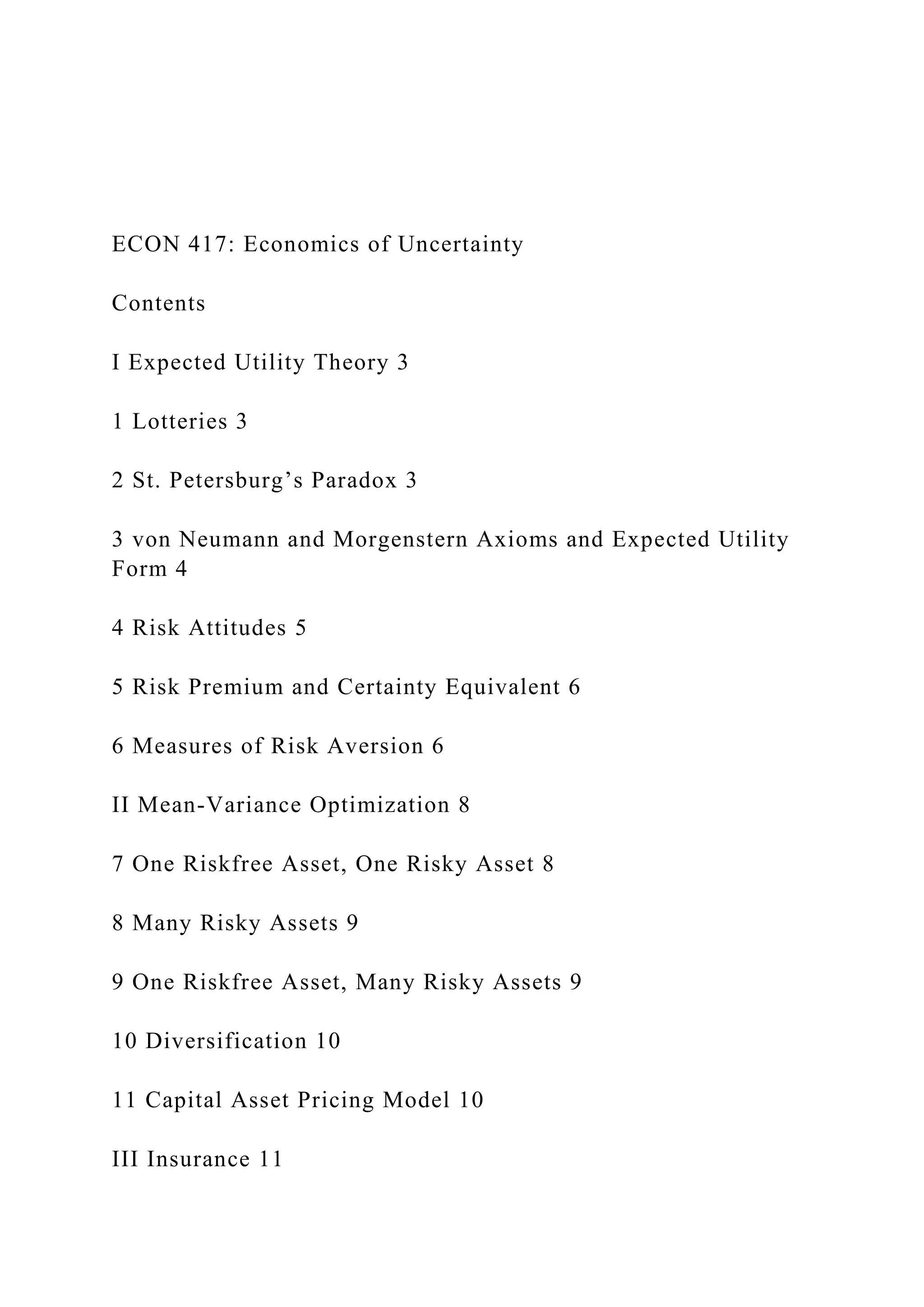

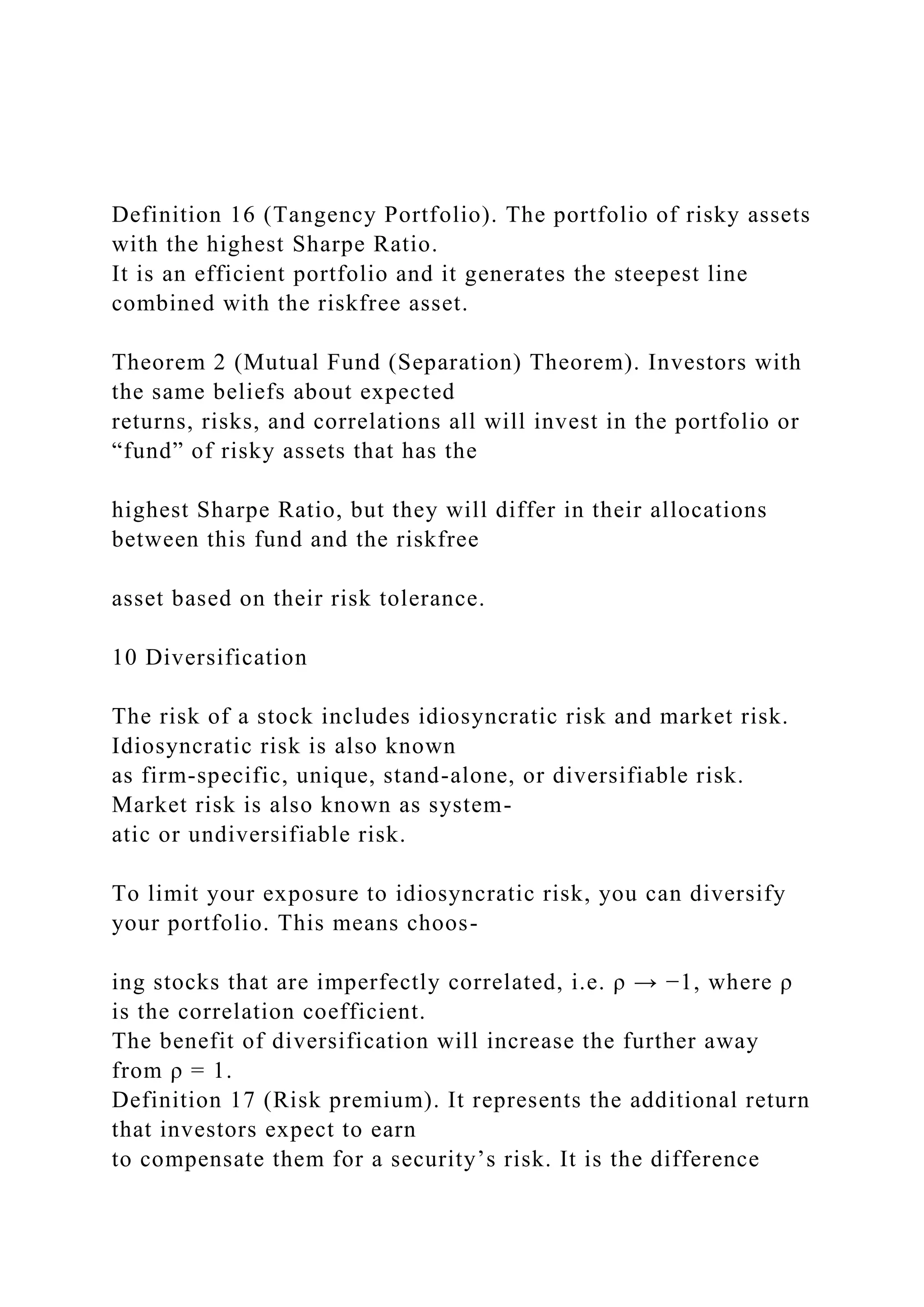

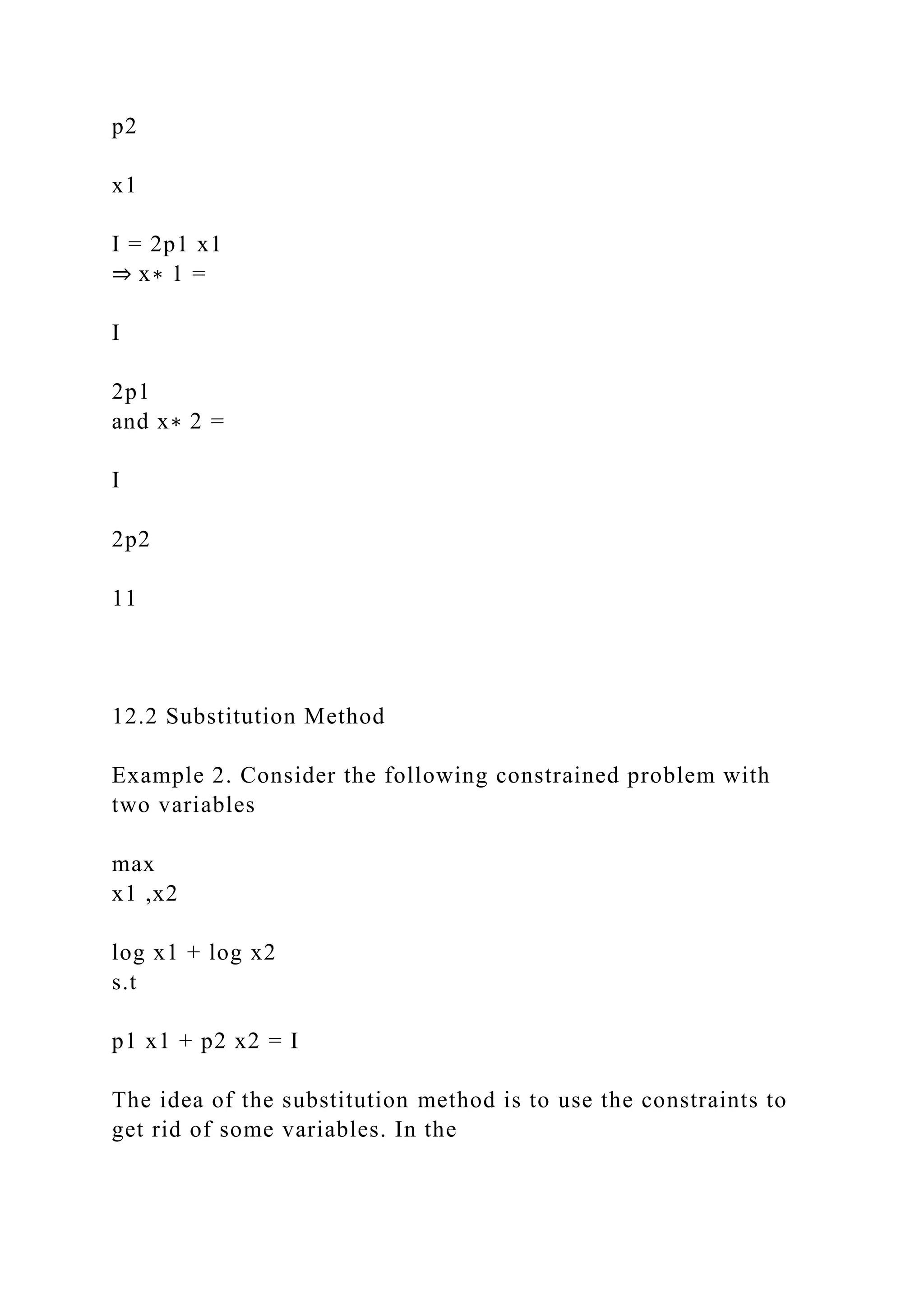

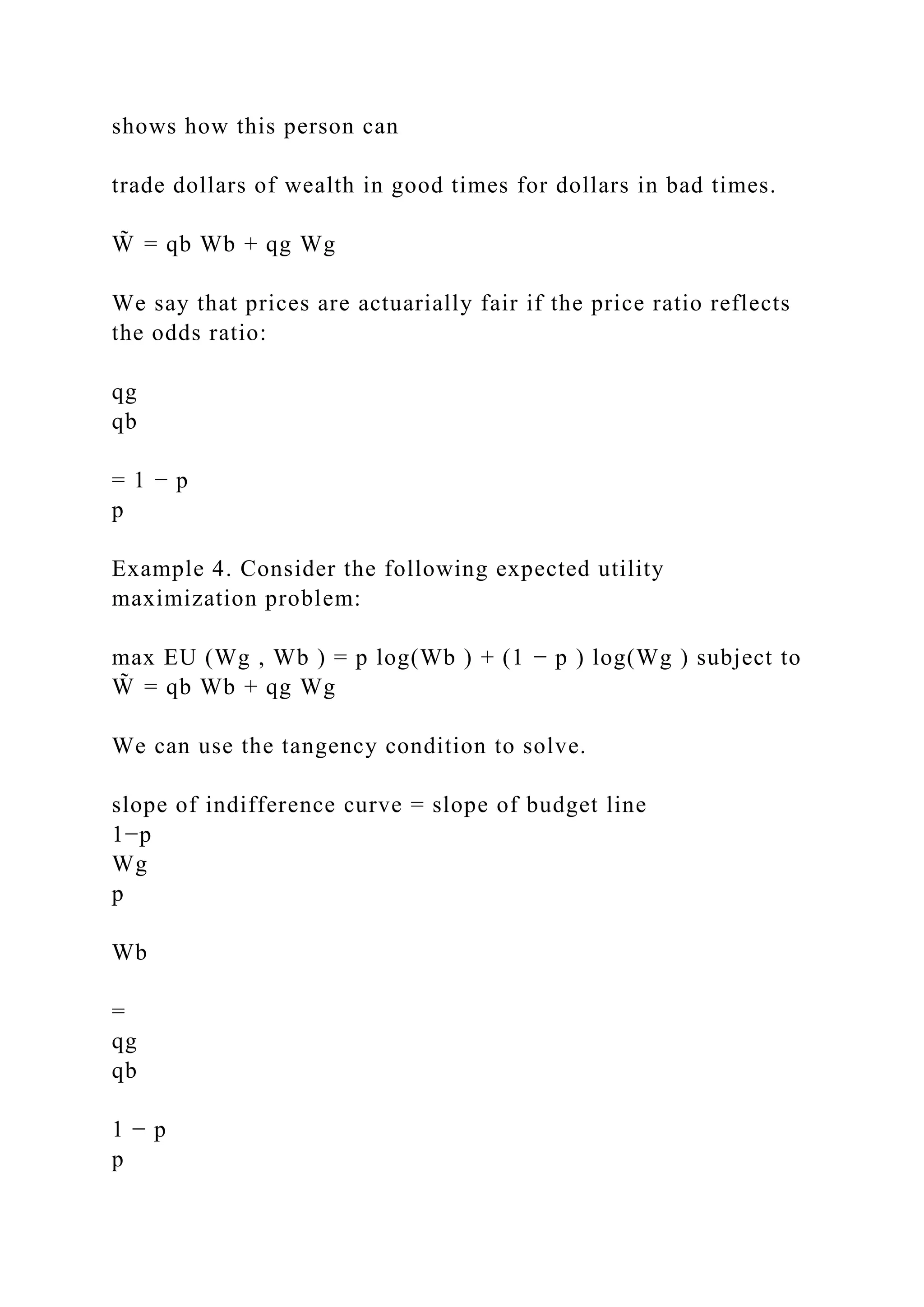

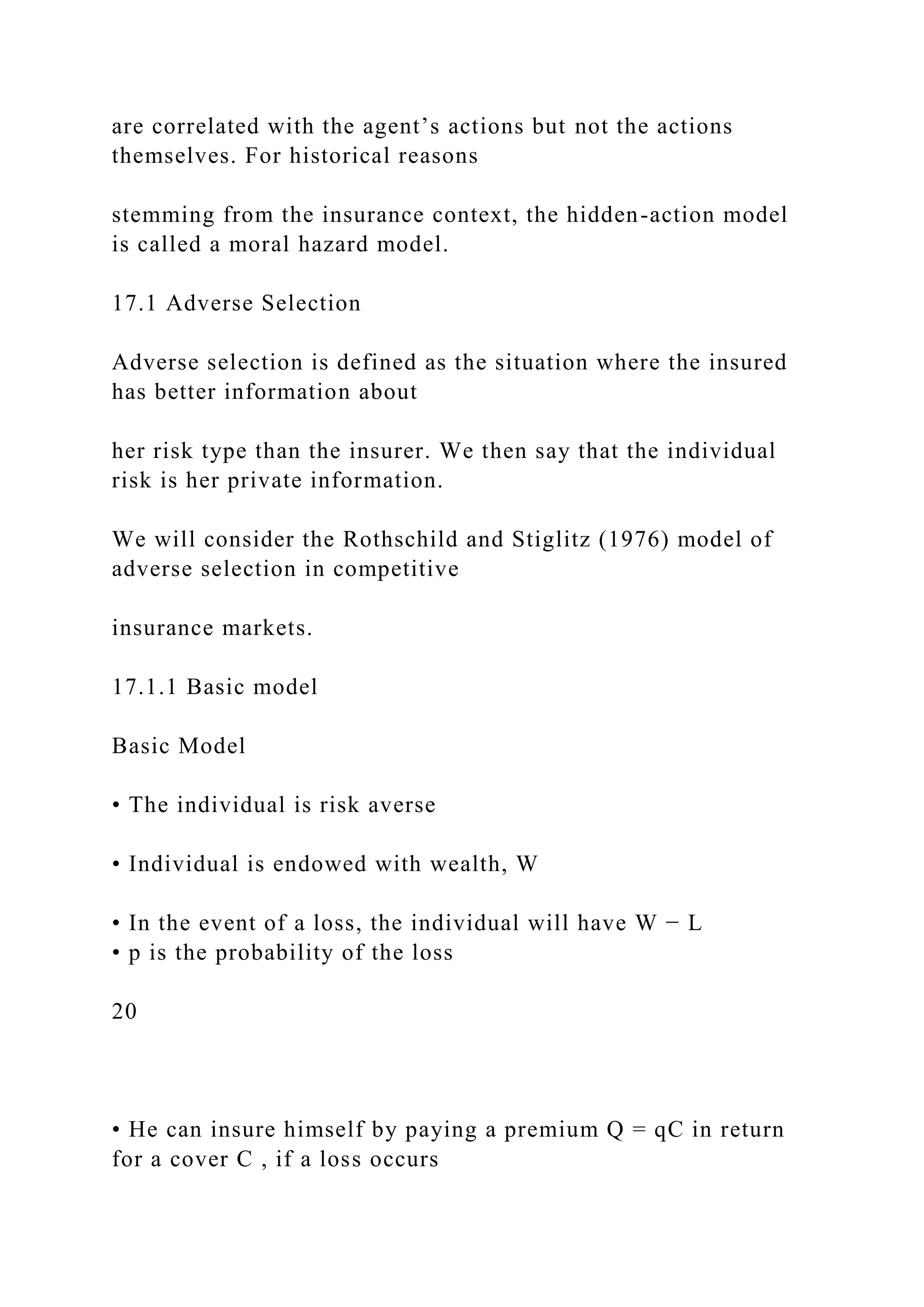

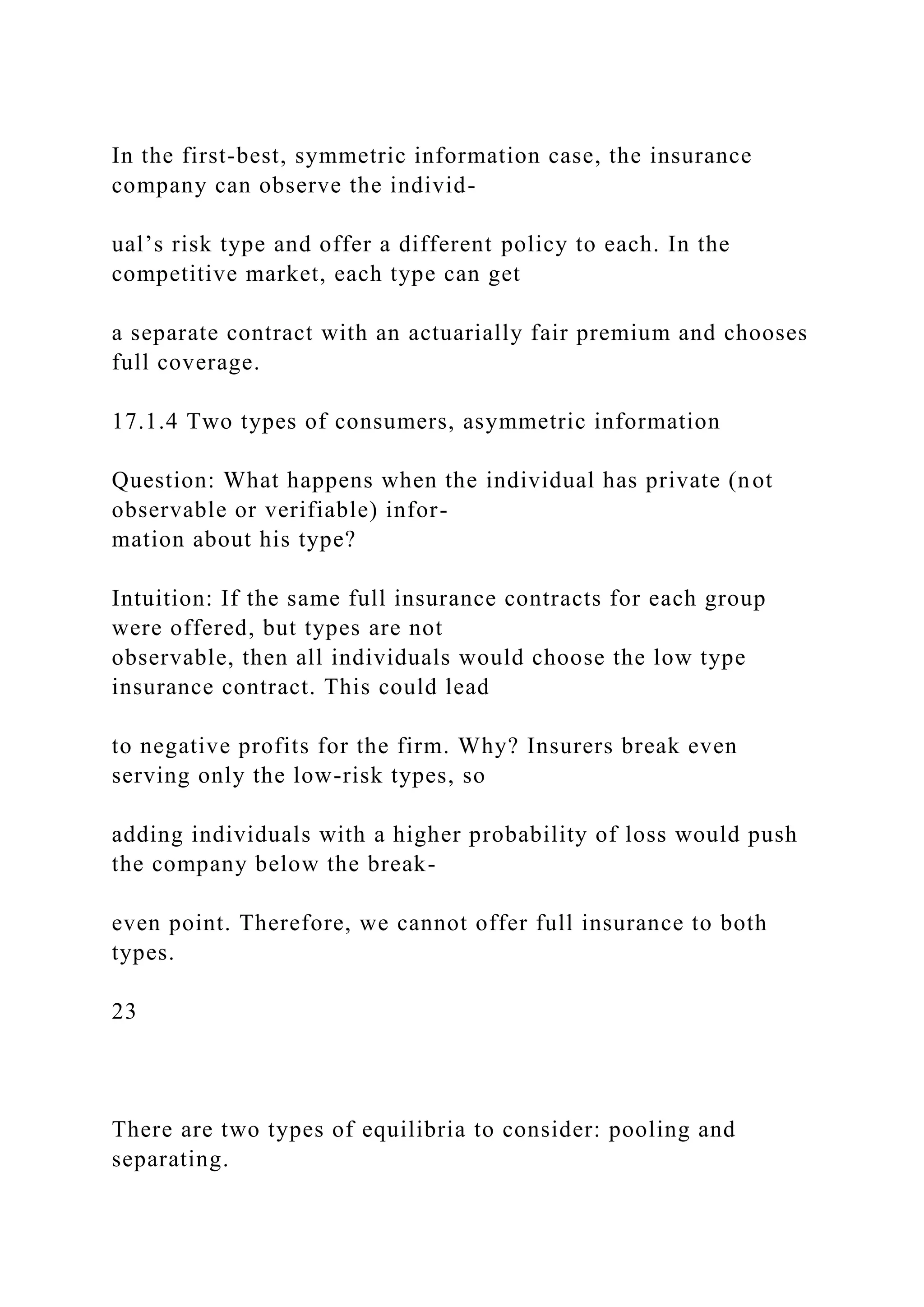

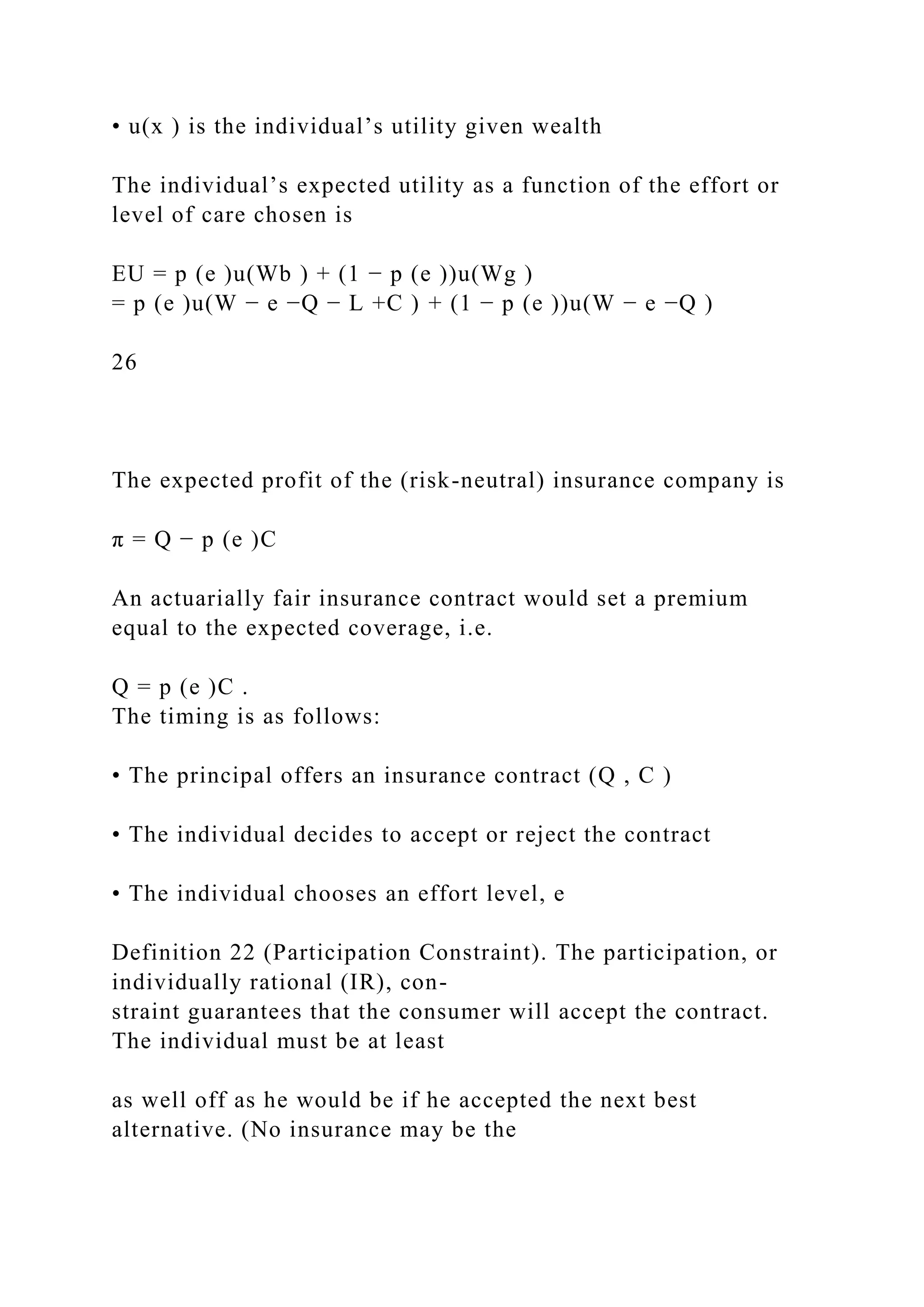

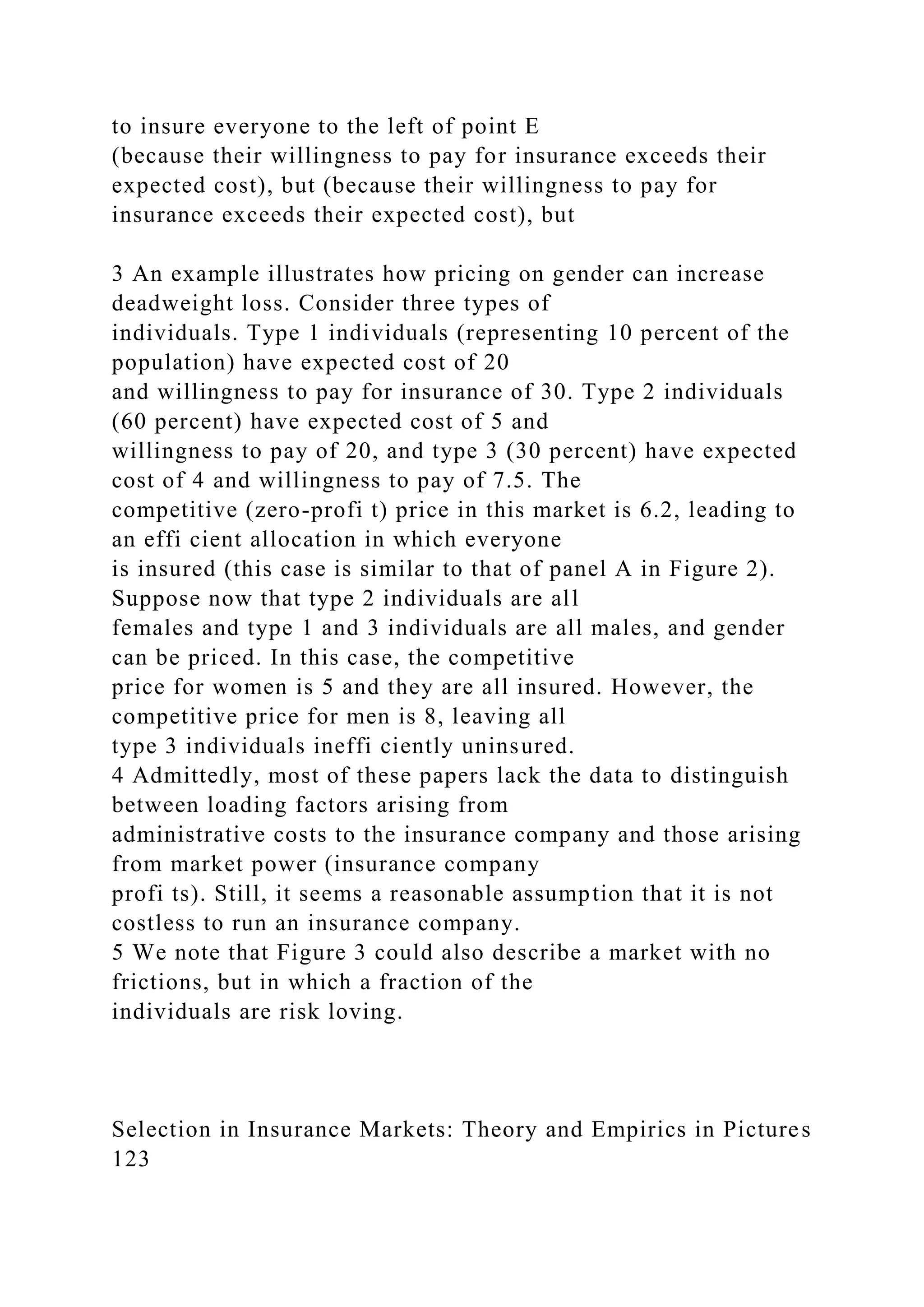

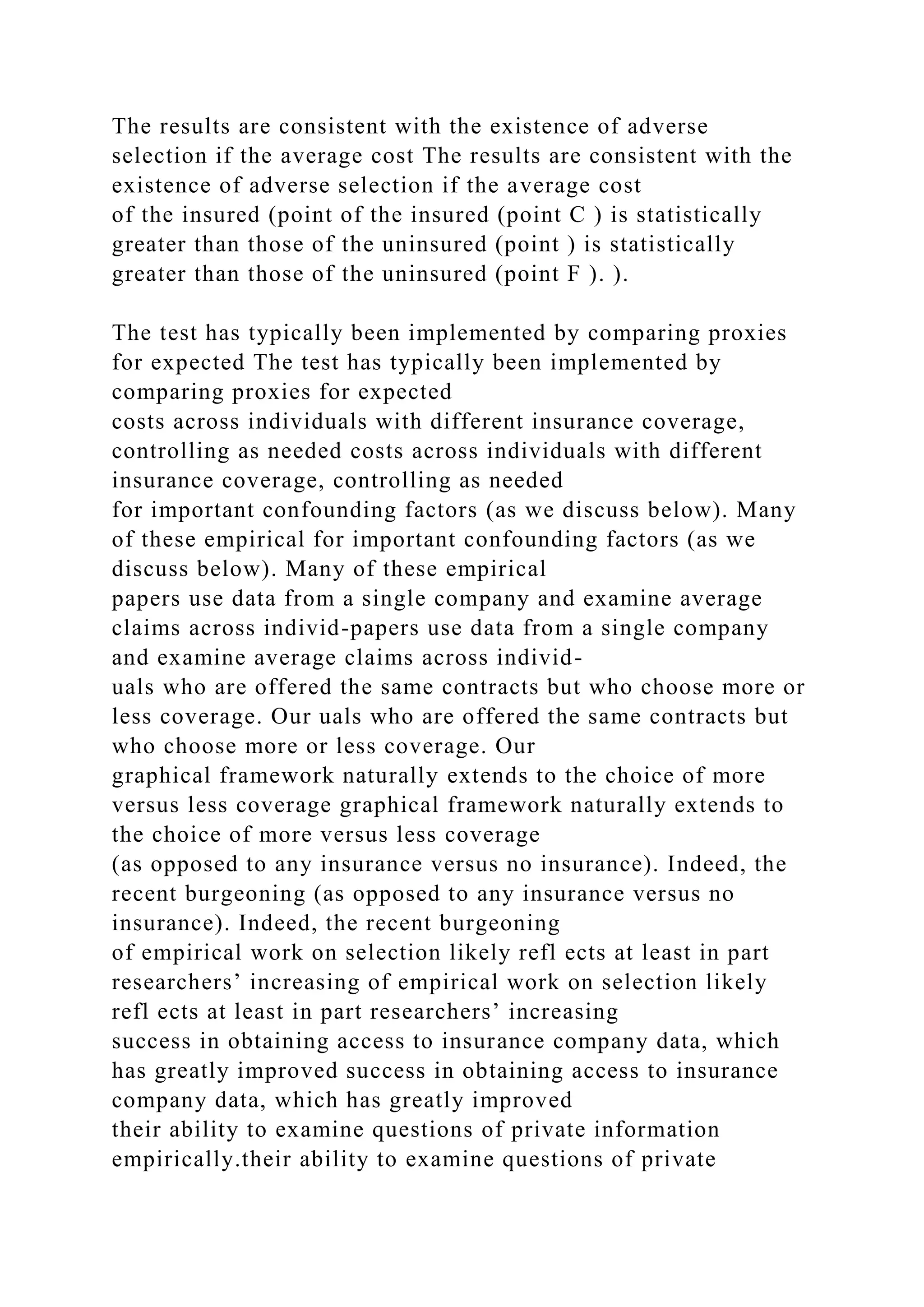

Proposition 3 (By the Law of Large Numbers).

lim

N →∞

Pr[|C

̄ N −µ| < ²] = 1

In words, as N becomes increasingly large, the average loss per

contract will be arbitrarily close

to the value µ with probability approaching 1.

2A sample is a (randomly) generated subset of the population

under study. The parameters of the population in-

clude its mean, µ, variance, σ2, and its standard deviation, σ.

The statistics of the sample include the sample mean

(or average), X

̄ = 1N

∑N

i =1 X i , the (unbiased) sample variance is s

2 = 1N −1

∑N

i =1(X i − X

̄ )2, and the sample standard

error is the sample standard deviation divided by the square root

of the sample size, i.e. sp

N

.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/econ417economicsofuncertaintycontentsiexpectedu-221031050641-9b4fc79f/75/ECON-417-Economics-of-UncertaintyContentsI-Expected-U-docx-39-2048.jpg)

![Research, Cambridge, Massachusetts. Their e-mail addresses are

Research, Cambridge, Massachusetts. Their e-mail addresses are

⟨ ⟨ [email protected]@stanford.edu⟩ ⟩ and and

⟨ ⟨ afi [email protected][email protected]⟩ ⟩ ..

doi=10.1257/jep.25.1.115

Liran Einav and Amy Finkelstein

116 Journal of Economic Perspectives

In this essay, we present a graphical framework for analyzing

both theoretical In this essay, we present a graphical framework

for analyzing both theoretical

and empirical work on selection in insurance markets. This

graphical approach, and empirical work on selection in

insurance markets. This graphical approach,

which draws heavily on a paper we wrote with Mark Cullen

(Einav, Finkelstein, and which draws heavily on a paper we

wrote with Mark Cullen (Einav, Finkelstein, and

Cullen, 2010), provides both a useful and intuitive depiction of

the basic theory of Cullen, 2010), provides both a useful and

intuitive depiction of the basic theory of

selection and its implications for welfare and public policy, as

well as a lens through selection and its implications for welfare

and public policy, as well as a lens through

which one can understand the ideas and limitations of existing

empirical work on which one can understand the ideas and

limitations of existing empirical work on

this topic.this topic.

We begin by using this framework to review the “textbook”

adverse selection We begin by using this framework to review

the “textbook” adverse selection](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/econ417economicsofuncertaintycontentsiexpectedu-221031050641-9b4fc79f/75/ECON-417-Economics-of-UncertaintyContentsI-Expected-U-docx-57-2048.jpg)

![1. Jason Brown, Mark Duggan, Ilyana Kuziemko, William

Woolston. 2014. How Does Risk Selection

Respond to Risk Adjustment? New Evidence from the Medicare

Advantage Program. American

Economic Review 104:10, 3335-3364. [Abstract] [View PDF

article] [PDF with links]

2. Denise Doiron, Denzil G. Fiebig, Agne Suziedelyte. 2014.

Hips and hearts: The variation in incentive

effects of insurance across hospital procedures. Journal of

Health Economics 37, 81-97. [CrossRef]

3. Timothy Harris, Aaron Yelowitz. 2014. Is there adverse

selection in the life insurance market? Evidence

from a representative sample of purchasers. Economics Letters .

[CrossRef]

4. Yiyan Liu, Ginger Zhe Jin. 2014. Employer contribution and

premium growth in health insurance.

Journal of Health Economics . [CrossRef]

5. David de Meza, Gang Xie. 2014. The deadweight gain of

insurance taxation when risky activities are

optional. Journal of Public Economics 115, 109-116. [CrossRef]

6. JOSEPH P. NEWHOUSE, THOMAS G. McGUIRE. 2014.

How Successful Is Medicare Advantage?.

Milbank Quarterly 92:2, 351-394. [CrossRef]

7. Thomas G. McGuire, Joseph P. Newhouse, Sharon-Lise

Normand, Julie Shi, Samuel Zuvekas. 2014.

Assessing incentives for service-level selection in private health

insurance exchanges. Journal of Health

Economics 35, 47-63. [CrossRef]

8. Andreas Richter, Jörg Schiller, Harris Schlesinger. 2014.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/econ417economicsofuncertaintycontentsiexpectedu-221031050641-9b4fc79f/75/ECON-417-Economics-of-UncertaintyContentsI-Expected-U-docx-132-2048.jpg)

![Behavioral insurance: Theory and

experiments. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty 48:2, 85-96.

[CrossRef]

9. Amy Finkelstein, James Poterba. 2014. Testing for

Asymmetric Information Using “Unused

Observables” in Insurance Markets: Evidence from the U.K.

Annuity Market. Journal of Risk and

Insurance n/a-n/a. [CrossRef]

10. R.P. Ellis, T.J. LaytonRisk Selection and Risk Adjustment

289-297. [CrossRef]

11. Yi (Kitty) Yao. 2013. Development and Sustainability of

Emerging Health Insurance Markets:

Evidence from Microinsurance in Pakistan. The Geneva Papers

on Risk and Insurance Issues and Practice

38:1, 160-180. [CrossRef]

12. Raj Chetty, Amy FinkelsteinSocial Insurance: Connecting

Theory to Data 111-193. [CrossRef]

13. Yong-Woo Lee. 2012. Asymmetric information and the

demand for private health insurance in Korea.

Economics Letters 116:3, 284-287. [CrossRef]

14. Meliyanni Johar, Elizabeth Savage. 2012. Sources of

advantageous selection: Evidence using actual

health expenditure risk. Economics Letters 116:3, 579-582.

[CrossRef]

15. Valentino Dardanoni, Paolo Li Donni. 2012. Incentive and

selection effects of Medigap insurance on

inpatient care. Journal of Health Economics 31:3, 457-470.

[CrossRef]

16. Jose A. Guajardo, Morris A. Cohen, Sang-Hyun Kim,](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/econ417economicsofuncertaintycontentsiexpectedu-221031050641-9b4fc79f/75/ECON-417-Economics-of-UncertaintyContentsI-Expected-U-docx-133-2048.jpg)

![Serguei Netessine. 2012. Impact of

Performance-Based Contracting on Product Reliability: An

Empirical Analysis. Management Science

58:5, 961-979. [CrossRef]

17. Thomas G. McGuireDemand for Health Insurance 2, 317-

396. [CrossRef]

http://dx.doi.org/10.1257/aer.104.10.3335

http://pubs.aeaweb.org/doi/pdf/10.1257/aer.104.10.3335

http://pubs.aeaweb.org/doi/pdfplus/10.1257/aer.104.10.3335

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2014.06.006

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.econlet.2014.07.029

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2014.08.006

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2014.02.004

http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1468-0009.12061

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2014.01.009

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11166-014-9188-x

http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/jori.12030

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-375678-7.00918-4

http://dx.doi.org/10.1057/gpp.2012.19

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-444-53759-1.00003-0

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.econlet.2012.03.021

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.econlet.2012.06.002

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2012.02.007

http://dx.doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.1110.1465

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-444-53592-4.00005-

0Selection in Insurance Markets: Theory and Empirics in

PicturesAdverse and Advantageous Selection: A Graphical

FrameworkThe Textbook Environment for Insurance

MarketsPublic Policy in the Textbook CaseDepartures from the

Textbook EnvironmentEmpirical Work on Selection“Positive

Correlation” Tests for Adverse SelectionChallenges in Applying

the Positive Correlation TestBeyond Testing: Quantifying

Selection EffectsConcluding CommentsReferences](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/econ417economicsofuncertaintycontentsiexpectedu-221031050641-9b4fc79f/75/ECON-417-Economics-of-UncertaintyContentsI-Expected-U-docx-134-2048.jpg)