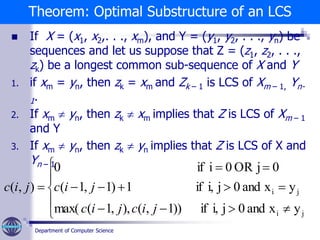

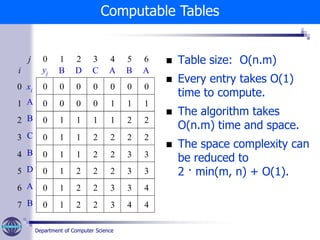

The document discusses the longest common subsequence (LCS) problem in bioinformatics. It defines the LCS problem as finding the longest string that is a subsequence of two given DNA strings. It presents an introduction to the problem, defines key terms like subsequence, and describes a brute force approach. The main part of the document presents a dynamic programming solution that uses optimal substructures of prefix sequences to solve the problem efficiently in polynomial time.

![Department of Computer Science

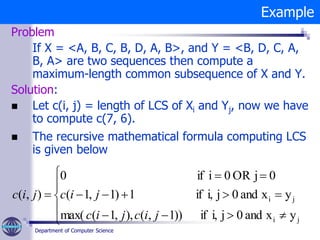

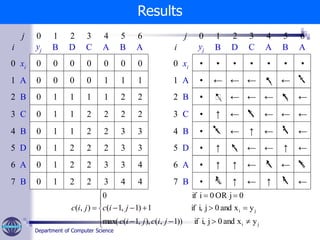

If X = <A, B, C, B, D, A, B>, Y = <B, D, C, A, B, A>

c(1, 1) = max (c(0, 1), c(1, 0)) = max (0, 0) = 0

b[1, 1] =

c(1, 2) = max (c(0, 2), c(1, 1)) = max (0, 0) = 0

b[1, 2] =

c(1, 3) = max (c(0, 3), c(1, 2)) = max (0, 0) = 0

b[1, 3] =

c(1, 4) = c(0, 3) + 1 = 0 + 1 = 1; b[1, 4] =

c(1, 5) = max (c(0, 5), c(1, 4)) = max (0, 1) = 1

b[1, 5] =

c(1, 6) = c(0, 5) + 1 = 0 + 1 = 1; b[1, 6] =

Example

↖](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dynamicprograminglcs-230409104032-a4b0a9e2/85/Dynamic-Programing_LCS-ppt-17-320.jpg)

![Department of Computer Science

If X = <A, B, C, B, D, A, B>, Y = <B, D, C, A, B, A>

c(2, 1) = c(1, 0) + 1 = 0 + 1 = 1; b[2, 1] =

c(2, 2) = max (c(1, 2), c(2, 1)) = max (0, 1) = 1

b[2, 2] =

c(2, 3) = max (c(1, 3), c(2, 2)) = max (0, 1) = 1

b[2, 3] =

c(2, 4) = max (c(1, 4), c(2, 3)) = max (1, 1) = 1

b[2, 4] =

c(2, 5) = c(1, 4) + 1 = 1 + 1 = 2; b[2, 5] =

c(2, 6) = max (c(1, 6), c(2, 5)) = max (1, 2) = 2

b[2, 6] =

Example

↖

↖](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dynamicprograminglcs-230409104032-a4b0a9e2/85/Dynamic-Programing_LCS-ppt-18-320.jpg)

![Department of Computer Science

If X = <A, B, C, B, D, A, B>, Y = <B, D, C, A, B, A>

c(3, 1) = max (c(2, 1), c(3, 0)) = max (1, 0) = 1

b[3, 1] =

c(3, 2) = max (c(2, 2), c(3, 1)) = max (1, 1) = 1

b[3, 2] =

c(3, 3) = c(2, 2) + 1 = 1 + 1 = 2; b[3, 3] =

c(3, 4) = max (c(2, 4), c(3, 3)) = max (1, 2) = 2

b[3, 4] =

c(3, 5) = max (c(2, 5), c(3, 4)) = max (2, 2) = 2

b[3, 5] =

c(3, 6) = max (c(2, 6), c(3, 5)) = max (2, 2) = 2

b[2, 6] =

Example

↖](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dynamicprograminglcs-230409104032-a4b0a9e2/85/Dynamic-Programing_LCS-ppt-19-320.jpg)

![Department of Computer Science

If X = <A, B, C, B, D, A, B>, Y = <B, D, C, A, B, A>

c(4, 1) = c(3, 0) + 1 = 0 + 1 = 1; b[4, 1] =

c(4, 2) = max (c(3, 2), c(4, 1)) = max (1, 1) = 1

b[4, 2] =

c(4, 3) = max (c(3, 3), c(4, 2)) = max (2, 1) = 2

b[4, 3] = ↑

c(4, 4) = max (c(3, 4), c(4, 3)) = max (2, 2) = 2

b[4, 4] =

c(4, 5) = c(3, 4) + 1 = 2 + 1 = 3; b[4, 5] =

c(4, 6) = max (c(3, 6), c(4, 5)) = max (2, 3) = 3

b[4, 6] =

Example

↖

↖](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dynamicprograminglcs-230409104032-a4b0a9e2/85/Dynamic-Programing_LCS-ppt-20-320.jpg)

![Department of Computer Science

If X = <A, B, C, B, D, A, B>, Y = <B, D, C, A, B, A>

c(5, 1) = max (c(4, 1), c(5, 0)) = max (1, 0) = 1

b[5, 1] = ↑

c(5, 2) = c(4, 1) + 1 = 1 + 1 = 2; b[5, 2] =

c(5, 3) = max (c(4, 3), c(5, 2)) = max (2, 2) = 2

b[5, 3] =

c(5, 4) = max (c(4, 4), c(5, 3)) = max (2, 2) = 2

b[5, 4] =

c(5, 5) = max (c(4, 5), c(5, 4)) = max (3, 2) = 3

b[5, 5] = ↑

c(5, 6) = max (c(4, 6), c(5, 5)) = max (3, 3) = 3

b[5, 6] =

Example

↖](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dynamicprograminglcs-230409104032-a4b0a9e2/85/Dynamic-Programing_LCS-ppt-21-320.jpg)

![Department of Computer Science

If X = <A, B, C, B, D, A, B>, Y = <B, D, C, A, B, A>

c(6, 1) = max (c(5, 1), c(6, 0)) = max (1, 0) = 1

b[6, 1] = ↑

c(6, 2) = max (c(5, 2), c(6, 1)) = max (2, 1) = 2

b[6, 1] = ↑

c(6, 3) = max (c(5, 3), c(6, 2)) = max (2, 2) = 2

b[6, 3] =

c(6, 4) = c(5, 3) + 1 = 2 + 1 = 3; b[6, 4] =

c(6, 5) = max (c(5, 5), c(6, 4)) = max (2, 3) = 3

b[6, 5] =

c(6, 6) = c(5, 5) + 1 = 3 + 1 = 4; b[6, 6] =

Example

↖

↖](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dynamicprograminglcs-230409104032-a4b0a9e2/85/Dynamic-Programing_LCS-ppt-22-320.jpg)

![Department of Computer Science

If X = <A, B, C, B, D, A, B>, Y = <B, D, C, A, B, A>

c(7, 1) = c(6, 0) + 1 = 0 + 1 = 1; b[7, 1] =

c(7, 2) = max (c(6, 2), c(7, 1)) = max (2, 1) = 2

b[7, 2] = ↑

c(7, 3) = max (c(6, 3), c(7, 2)) = max (2, 2) = 2

b[7, 3] =

c(7, 4) = max (c(6, 4), c(7, 3)) = max (3, 2) = 3

b[7, 4] = ↑

c(7, 5) = c(6, 4) + 1 = 3 + 1 = 4; b[7, 5] =

c(7, 6) = max (c(6, 6), c(7, 5)) = max (4, 4) = 4

b[7, 6] =

Example

↖

↖](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dynamicprograminglcs-230409104032-a4b0a9e2/85/Dynamic-Programing_LCS-ppt-23-320.jpg)

![Department of Computer Science

c[i, j] = c(i-1, j-1) + 1 if xi = yj;

c[i, j] = max( c(i-1, j), c(i, j-1)) if xi ≠ yj;

c[i, j] = 0 if (i = 0) or (j = 0).

function LCS(X, Y)

1 m length [X]

2 n length [Y]

3 for i 1 to m

4 do c[i, 0] 0;

5 for j 1 to n

6 do c[0, j] 0;

Longest Common Subsequence Algorithm](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dynamicprograminglcs-230409104032-a4b0a9e2/85/Dynamic-Programing_LCS-ppt-28-320.jpg)

![Department of Computer Science

c[i, j] = c(i-1, j-1) + 1 if xi = yj;

c[i, j] = max( c(i-1, j), c(i, j-1)) if xi ≠ yj;

c[i, j] = 0 if (i = 0) or (j = 0).

7. for i 1 to m

8 do for j 1 to n

9 do if (xi = = yj)

10 then c[i, j] c[i-1, j-1] + 1

11 b[i, j] “ ”

12 else if c[i-1, j] c[i, j-1]

13 then c[i, j] c[i-1, j]

14 b[i, j] “↑”

15 else c[i, j] c[i, j-1]

16 b[i, j] “”

17 Return c and b;

Longest Common Subsequence Algorithm](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dynamicprograminglcs-230409104032-a4b0a9e2/85/Dynamic-Programing_LCS-ppt-29-320.jpg)

![Department of Computer Science

c[i, j] = c(i-1, j-1) if xi = yj;

c[i, j] = min( c(i-1, j), c(i, j-1)) if xi ≠ yj;

c[i, j] = 0 if (i = 0) or (j = 0).

procedure PrintLCS(b, X, i, j)

1. if (i == 0) or (j == 0)

2. then return

3. if b[i, j] == “ ”

4. then PrintLCS(b, X, i-1, j-1)

5. Print xi

6. else if b[i, j] “↑”

7. then PrintLCS(b, X, i-1, j)

8 else PrintLCS(b, X, i, j-1)

Construction of Longest Common Subsequence](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dynamicprograminglcs-230409104032-a4b0a9e2/85/Dynamic-Programing_LCS-ppt-30-320.jpg)

![Department of Computer Science

Problem Statement

The two sequences X and Y are given and task is to

find a shortest possible common supersequence.

Shortest common supersequence is not unique.

Easy to make SCS from LCS for 2 input sequences.

Example,

X[1..m] = abcbdab

Y[1..n] = bdcaba

LCS = Z[1..r] = bcba

Insert non-lcs symbols preserving order, we get

SCS = U[1..t] = abdcabdab.

Relationship with shortest common supper-sequence](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dynamicprograminglcs-230409104032-a4b0a9e2/85/Dynamic-Programing_LCS-ppt-32-320.jpg)