The document presents a framework called Karma for performing list-based monadic computations in dynamically typed languages, offering an alternative to object-oriented programming by using higher-order functions and types. It introduces karmic types and the concepts of bind and wrap to manage function composition and state effectively, allowing for the seamless combination of computations, including fallible and stateful ones. The discussion also touches on parser combinators and provides examples using Perl and Livescript, showcasing how to build complex parsers for specific languages.

![Perl ...

Notorious

$_=’while(read+STDIN,$_,2048){$a=29;$b=73;

$c=142;$t=255;@t=map{$_%16or$t^=$c^=($m=

(11,10,116,100,11,122,20,100)[$_/16%8])&110;

$t^=(72,@z=(64,72,$a^=12*($_%16 -2?0:$m&17)),

$b^=$_%64?12:0,@z)[$_%8]}(16..271);

if((@a=unx"C*",$_)[20]&48){$h =5;$_=unxb24,

join"",@b=map{xB8,unxb8,chr($_^$a[--$h+84])}

@ARGV;s/...$/1$&/;$ d=unxV,xb25,$_;$e=256|

(ord$b[4])<<9|ord$b[3];$d=$d>>8^($f=$t&

($d>>12^$d>>4^$d^$d/8))<<17,$e=$e>>8^($t

&($g=($q=$e>>14&7^$e)^$q*8^$q<<6))<<9,$_=

$t[$_]^(($h>>=8)+=$f+(~$g&$t))for

@a[128..$#a]}print+x"C*",@a}’;s/x/pack+/g;

eval;

But I like Perl (*ducks*)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dyla-talk-2014-06-12-pub-140613034436-phpapp01/85/List-based-Monadic-Computations-for-Dynamic-Languages-4-320.jpg)

![Syntactic Sugar for Karma

Our approach:

Use lists to combine computations

For example:

[

word,

maybe parens choice

natural,

[

symbol ’kind’,

symbol ’=’,

natural

]

]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dyla-talk-2014-06-12-pub-140613034436-phpapp01/85/List-based-Monadic-Computations-for-Dynamic-Languages-19-320.jpg)

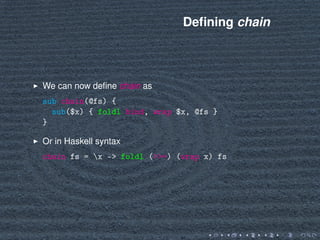

![Designing Karma

Grouping items in lists provides a natural sequencing

mechanism, and allows easy nesting.

In most dynamic languages, lists us the [...,...] syntax, it’s

portable and non-obtrusive.

We introduce a chain function to chain computations together.

Pass chain a list of functions and it will combine these functions

into a single expression.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dyla-talk-2014-06-12-pub-140613034436-phpapp01/85/List-based-Monadic-Computations-for-Dynamic-Languages-20-320.jpg)

![Preliminary: fold

To define chain in terms of bind and wrap, we need the left fold

function (foldl).

foldl performs a left-to-right reduction of a list via iterative

application of a function to an initial value:

foldl :: (a → b → a) → a → [b] → [a]

A possible implementation e.g. in Perl would be

sub foldl ($f, $acc, @lst) {

for my $elt (@lst) {

$acc=$f->($acc,$elt)

}

return $acc

}](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dyla-talk-2014-06-12-pub-140613034436-phpapp01/85/List-based-Monadic-Computations-for-Dynamic-Languages-21-320.jpg)

![Karma Needs Dynamic Typing

The above definition of chain is valid in Haskell, but only if the

type signature is

chain :: [(a → m a)] → (a → m a)

But the type of bind is bind :: m a → (a → m b) → m b

the karmic type m b returned by bind does not have to be the same

as the karmic type argument m a.

every function in the list passed to chain should be allowed to have

a different type!

This is not allowed in a statically typed language like Haskell, so

only the restricted case of functions of type a → m a can be

used.

However, in a dynamically typed language there is no such

restriction, so we can generalise the type signature:

chain :: [(ai−1 → m ai )] → (a0 → m aN ) ∀i ∈ 1 .. N](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dyla-talk-2014-06-12-pub-140613034436-phpapp01/85/List-based-Monadic-Computations-for-Dynamic-Languages-23-320.jpg)

![Combining Fallible Computations (2)

Without karma

v1 = f(x)

if (v1.ok)

v2=g(v1.val)

if (v2.ok)

v3 = h(v2.val)

if (v3.ok)

v3.val

else

fail

end

else

fail

end

else

fail

end

With karma:

comp = chain [

->(x) {f x},

->(y) {g y},

->(z) {h z}

]

v1=comp.call x

If f, g and h are defined as

lambda functions:

comp =

chain [ f,g,h ]

v1=comp.call x](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dyla-talk-2014-06-12-pub-140613034436-phpapp01/85/List-based-Monadic-Computations-for-Dynamic-Languages-26-320.jpg)

![State Concept and API

We simulate state by combining functions that transform the

state, and applying the resulting function to an initial state

(approach borrowed from Haskell’s Control.State).

A small API to allow the functions in the list to access a shared

state:

get = -> ( (s) -> [s, s] )

put = (s) -> ( -> [[],s])

The get function reads the state, the put function writes an

updated state. Both return lambda functions.

A top-level function to apply the stateful computation to an initial

state:

res = evalState comp, init

where

evalState = (comp,init) -> comp!(init)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dyla-talk-2014-06-12-pub-140613034436-phpapp01/85/List-based-Monadic-Computations-for-Dynamic-Languages-29-320.jpg)

![Trivial Interpreter:

Instructions

We want to interpret a list of instructions of type

type Instr = (String, ([Int] → Int, [a]))

For example

instrs = [

["v1",[set,[1]]],

["v2",[add,["v1",2]]],

["v2",[mul,["v2","v2"]]],

["v1",[add,["v1","v2"]]],

["v3",[mul,["v1","v2"]]]

]

where add, mul and set are functions of type [Int] → Int

The interpreter should return the final values for all variables.

The interpreter will need a context for the variables, we use a

simple map { String : Int } to store the values for each variable.

This constitutes the state of the computation.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dyla-talk-2014-06-12-pub-140613034436-phpapp01/85/List-based-Monadic-Computations-for-Dynamic-Languages-30-320.jpg)

![Trivial Interpreter:

the Karmic Function

We write a function interpret_instr_st :: Instr → [[a], Ctxt]:

interpret_instr_st = (instr) ->

chain( [

get,

(ctxt) ->

[v,res] = interpret_instr(instr, ctxt)

put (insert v, res, ctxt)

] )

interpret_instr_st

gets the context from the state,

uses it to compute the instruction,

updates the context using the insert function and

puts the context back in the state.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dyla-talk-2014-06-12-pub-140613034436-phpapp01/85/List-based-Monadic-Computations-for-Dynamic-Languages-31-320.jpg)

![Trivial Interpreter:

the Stateless Function

Using Ctxt as the type of the context, the type of interpret_instr is

interpret_instr :: Instr → Ctxt → (String, Int) and the

implementation is straightforward:

interpret_instr = (instr, ctxt) ->

[v,rhs] = instr # unpacking

[op,args] = rhs # unpacking

vals = map (‘get_val‘ ctxt), args

[v, op vals]

get_val looks up the value of a variable in the context; it is

backticked into an operator here to allow partial application.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dyla-talk-2014-06-12-pub-140613034436-phpapp01/85/List-based-Monadic-Computations-for-Dynamic-Languages-32-320.jpg)

![bind and wrap for State

For the State karmic type, bind is defined as:

bind = (f,g) ->

(st) ->

[x,st_] = f st

(g x) st_

and wrap as

wrap = (x) -> ( (s) -> [x,s] )](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dyla-talk-2014-06-12-pub-140613034436-phpapp01/85/List-based-Monadic-Computations-for-Dynamic-Languages-33-320.jpg)

![modify: Modifying the State

The pattern of calling get to get the state, then computing using

the state and then updating the state using put is very common.

So we combine it in a function called modify:

modify = (f) ->

chain( [

get,

(s) -> put( f(s))

] )

Using modify we can rewrite interpret_instr_st as

interpret_instr_st = (instr) ->

modify (ctxt) ->

[v,res] = interpret_instr(instr, ctxt)

insert v, res, ctxt](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dyla-talk-2014-06-12-pub-140613034436-phpapp01/85/List-based-Monadic-Computations-for-Dynamic-Languages-34-320.jpg)

![mapM: a Dynamic chain

We could in principle use chain to write a list of computations on

each instruction:

chain [

interpret_instr_st instrs[0],

interpret_instr_st instrs[1],

interpret_instr_st instrs[2],

...

]

but clearly this is not practical as it is entirely static.

Instead, we use a monadic variant of the map function, mapM:

mapM :: Monad m ⇒ (a → m b) → [a] → m [b]

mapM applies the computations to the list of instructions (using

map) and then folds the resulting list using bind.

With mapM, we can simply write :

res = evalState (mapM interpret_instr_st, instrs), {}](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dyla-talk-2014-06-12-pub-140613034436-phpapp01/85/List-based-Monadic-Computations-for-Dynamic-Languages-35-320.jpg)

![Parser Combinator Basics

Each basic parser returns a function which operates on a string

and returns a result.

Parser :: String → Result

The result is a tuple containing the status, the remaining string

and the substring(s) matched by the parser.

type Result = (Status, String, [Match])

To create a complete parser, the basic parsers are combined

using combinators.

A combinator takes a list of parsers and returns a parsing

function similar to the basic parsers:

combinator :: [Parser] → Parser](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dyla-talk-2014-06-12-pub-140613034436-phpapp01/85/List-based-Monadic-Computations-for-Dynamic-Languages-38-320.jpg)

![Karmic Parser Combinators

For example, a parser for a Fortran-95 type declaration:

my $parser = chain [

identifier,

maybe parens choice

natural,

[

symbol ’kind’,

symbol ’=’,

natural

]

];

In dynamic languages the actual chain combinator can be

implicit, i.e. a bare list will result in calling of chain on the list.

For statically typed languages this is of course not possible as all

elements in a list must have the same type.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dyla-talk-2014-06-12-pub-140613034436-phpapp01/85/List-based-Monadic-Computations-for-Dynamic-Languages-39-320.jpg)

![bind and wrap for Parser

For the Parser karmic type, bind is defined as (Perl):

sub bind($t, $p) {

my ($st_,$r_,$ms_) = @{$t};

if ($st_) {

($st,$r,$ms) = $p->($r_);

if ($st) {

(1,$r,[@{$ms_},@{$ms}]);

} else {

(0,$r,undef)

}

} else {

(0,$r_,undef)

}

and wrap as:

sub wrap($str){ (1,$str,undef) }](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dyla-talk-2014-06-12-pub-140613034436-phpapp01/85/List-based-Monadic-Computations-for-Dynamic-Languages-40-320.jpg)

![bind and wrap for Parser

For the Parser karmic type, bind is defined as (LiveScript):

bind = (t, p) ->

[st_,r_,ms_] = t

if st_ then

[st,r,ms] = p r_

if st then

[1,r,ms_ ++ ms]

else

[0,r,void]

else

[0,r_,void]

and wrap as:

wrap = (str) -> [1,str,void]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dyla-talk-2014-06-12-pub-140613034436-phpapp01/85/List-based-Monadic-Computations-for-Dynamic-Languages-41-320.jpg)

![Final Example (1)

Parsers can combine several other parsers, and can be labeled:

my $f95_arg_decl_parser =

chain [

whiteSpace,

{TypeTup => $type_parser},

maybe [

comma,

$dim_parser

],

maybe [

comma,

$intent_parser

],

symbol ’::’,

{Vars => sepBy ’,’,word}

];](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dyla-talk-2014-06-12-pub-140613034436-phpapp01/85/List-based-Monadic-Computations-for-Dynamic-Languages-42-320.jpg)

![Final Example (2)

We can run this parser e.g.

my $var_decl =

"real(8), dimension(0:ip,-1:jp+1,kp) :: u,v"

my $res =

run $f95_arg_decl_parser, $var_decl;

This results in the parse tree:

{

’TypeTup’ => {

’Type’ => ’real’,

’Kind’ => ’8’

},

’Dim’ => [’0:ip’,’-1:jp+1’,’kp’],

’Vars’ => [’u’,’v’]

}](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dyla-talk-2014-06-12-pub-140613034436-phpapp01/85/List-based-Monadic-Computations-for-Dynamic-Languages-43-320.jpg)