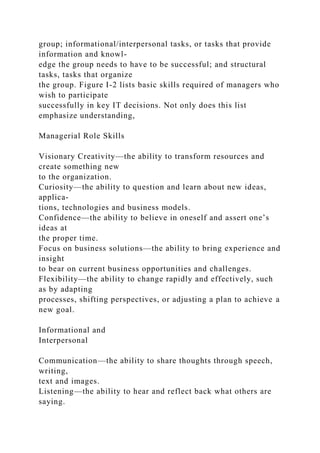

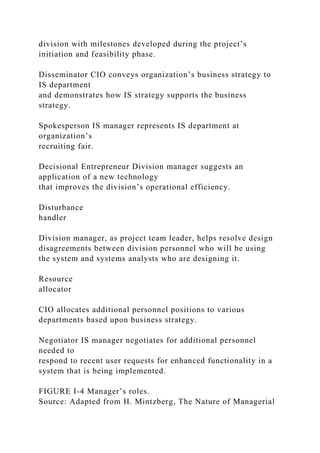

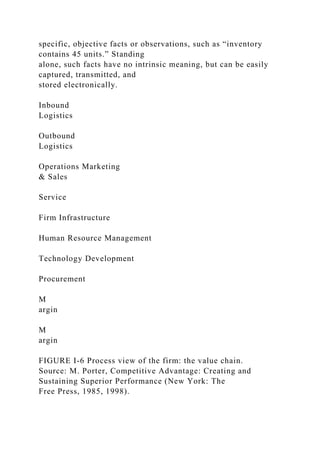

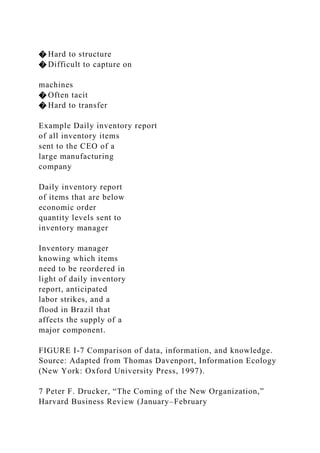

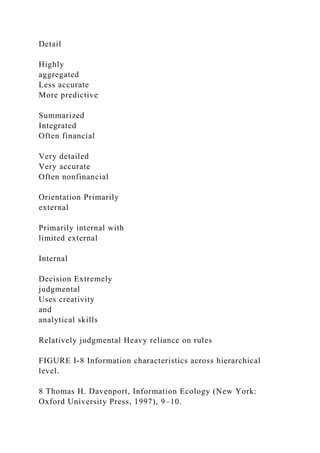

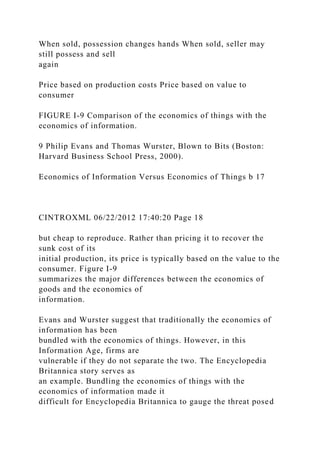

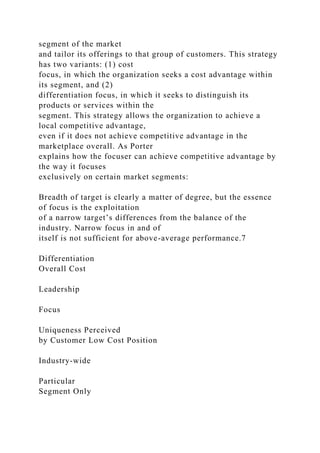

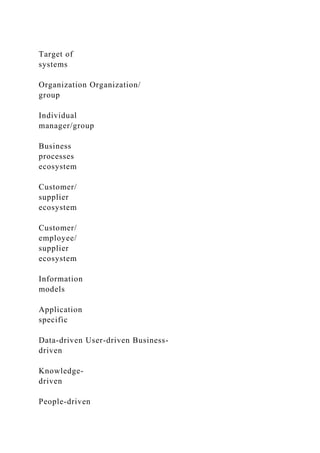

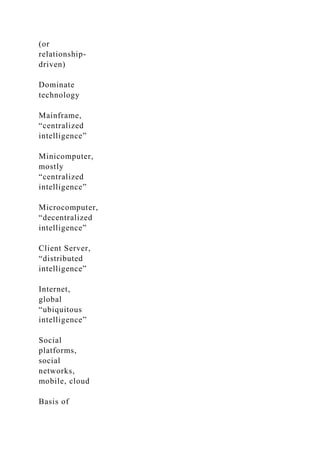

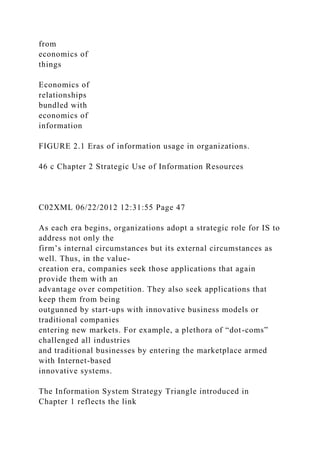

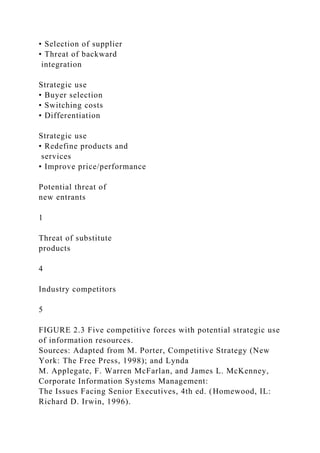

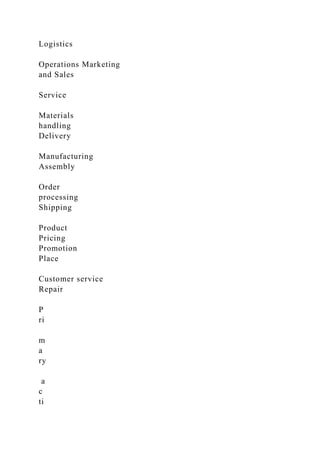

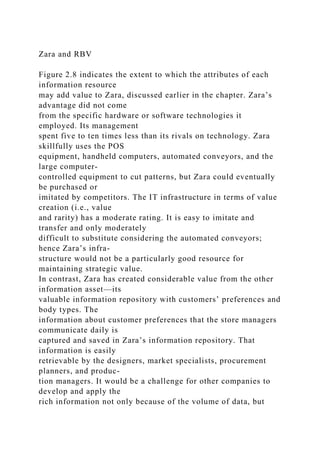

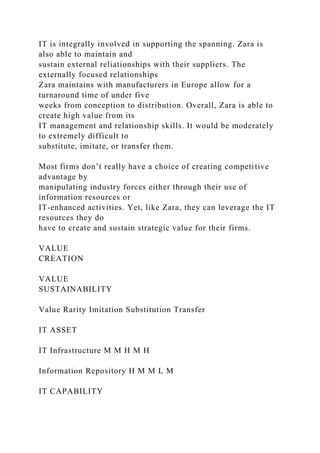

The document outlines the importance of information technology in organizations, highlighting its integral role in business interactions, processes, and decision-making. It emphasizes that managers must be knowledgeable participants in information systems decisions, as these systems influence the foundation of business operations. The text serves as a resource for current and future managers to understand and utilize information systems effectively, adapting to the changing technology landscape and the increasing data demands faced by organizations.