The document explores the integration of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) into fire service operations, detailing their historical military use and modern civilian applications, particularly for enhancing situational awareness and emergency response capabilities. It discusses regulatory requirements, operational challenges, and the financial implications of adopting drones in public safety, highlighting various missions and benefits, as well as the importance of training and maintenance. Additionally, it outlines potential funding sources to support the establishment of drone programs within fire departments.

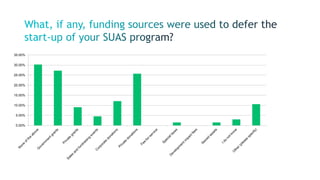

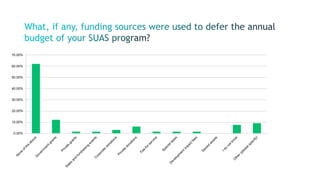

![Funding alternatives exist to mitigate the cost of sUAS programs (United States

Fire Administration [USFA], 2012). Options include government grants, private

grants, sales and fundraising events, corporate donations, private donations, fee

for service, special taxes, development impact fees, and seized assets, among

others (USFA, 2012).

Minimizing the financial burden of a new program on the local tax base may

facilitate government approval of an sUAS program (USFA, 2012). Ridgefield Fire

Department has a history of successfully acquiring grants and donations (Himes,

2012).

Fire departments in Connecticut have received donations to support sUAS

programs, including Danbury (Perrefort & Attanasio, 2018), Branford (Ball, 2014),

Putnam (Spires, 2020), Norwich (Penney, 2020), and West Hartford (FOX News

61, 2020).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dronesforfiredepartmentsuavs-230303174239-ddab012c/85/Drones-for-Fire-Departments-UAVs-pptx-43-320.jpg)