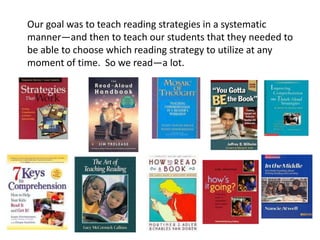

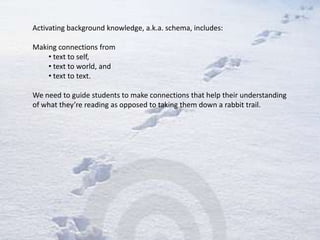

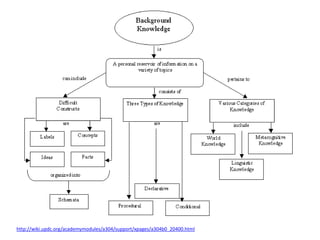

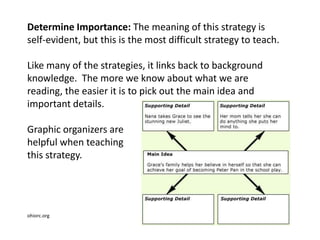

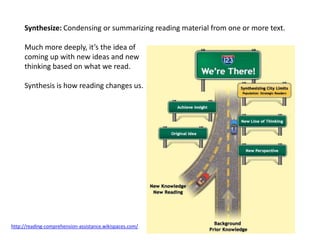

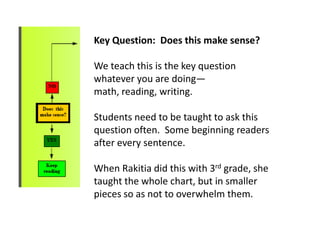

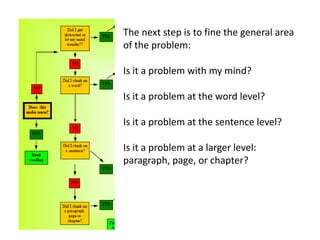

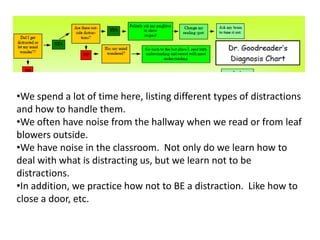

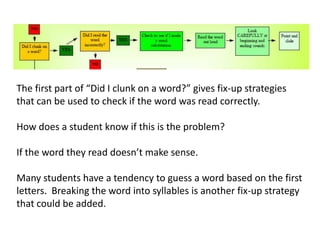

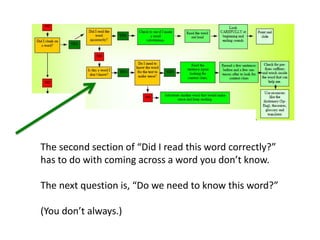

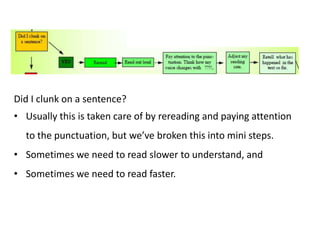

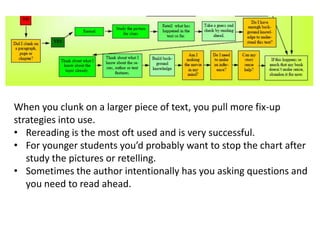

Dr. Goodreader was developed by Susan Stevens and Rakitia Delk to teach students reading strategies in a systematic way and enable them to self-diagnose problems and choose appropriate strategies, with the goal of moving from textbook instruction to reading workshops; it outlines strategies like metacognition, activating background knowledge, visualizing, inferring, questioning, determining importance, synthesizing, and evaluating.