This document discusses the importance of managing diversity in the workplace as a business strategy that enhances performance and competitive advantage. It outlines how diversity can help organizations expand into global markets, improve brand equity, support human resource strategies, enhance corporate image, and increase operational efficiency. The document also emphasizes that workforce diversity is not just a corporate obligation but a necessity for surviving in an increasingly globalized and service-oriented economy.

![heads a nonprofit organization dedicated to placing people with

disabilities in jobs. “Not one” he admitted. “As soon as I tell

them I can't walk, type, and other things I can't do, they get off

the telephone as quickly as possible.”

“I'm not surprised,” said the host. “Prospective employers want

to know what job applicants can do for them, not what their

limitations are. If you can show a prospective employer that you

will bring in customers, design a new product, or do something

else that makes a contribution, employers will hire you. Your

disability won't matter if you can prove that you will contribute

to the employer's bottom line.”79

The fact is that poll after poll of employers demonstrates that

they regard most people with disabilities, roughly 50 million in

the United States, as good workers, punctual, conscientious, and

competent—if given reasonable accommodation. Despite this

evidence, persons with disabilities are less likely to be working

than any other demographic group under age 65. One survey

found that two-thirds of persons with disabilities between the

ages of 16 and 64 are unemployed. They also worked

approximately one-third fewer hours than those without

disabilities.80 As Harvard Business School professor David

Thomas has noted: “When it comes to dealing with people with

disabilities, we are about where we were with race in the 1970s

… Companies by and large are doing the minimum to

accommodate [them]. Instead we should all be asking what is it

that companies can do to maximize their great talent.”81

Perhaps the biggest barrier is employers' lack of knowledge. For

example, many are concerned about financial hardship because

they assume it will be costly to make architectural changes to

accommodate wheelchairs and add equipment to aid workers

who are blind or deaf. In fact, statistics show that most

accommodations cost less than $1,000 per employee, 22 percent

cost more than $1,000, and 15 percent cost nothing.82 Consider

several possible modifications:83

· Placing a desk on blocks, lowering shelves, and using a

carousel for files are inexpensive accommodations that enable](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/diversityatworkquestionsthischapterwillhelpmanagersanswe-221026032732-01cc7112/75/Diversity-at-WorkQuestions-This-Chapter-Will-Help-Managers-Answe-docx-34-2048.jpg)

![that the employer's stated legitimate basis for its employment

decision is actually just a pretext for illegal discrimination.

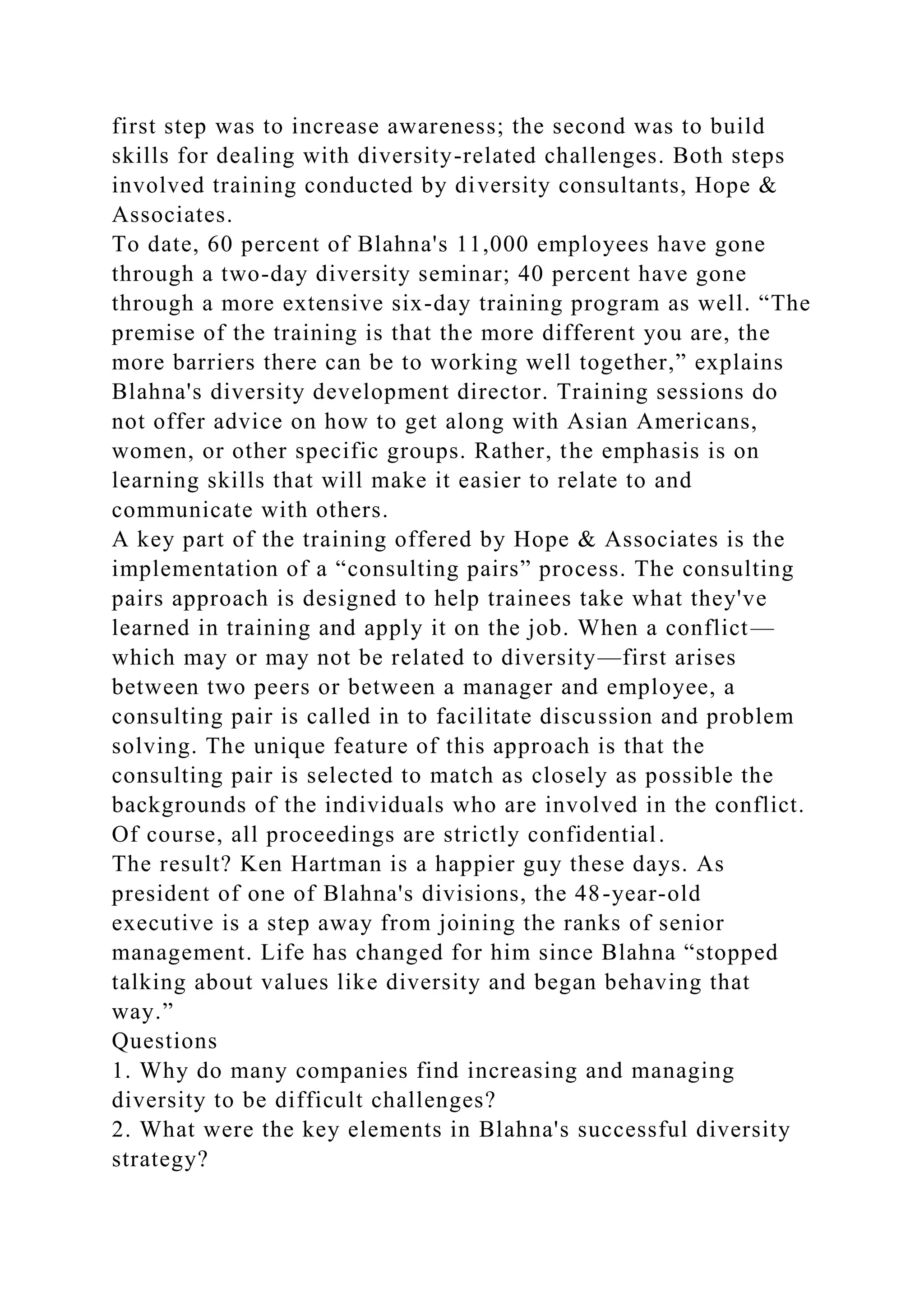

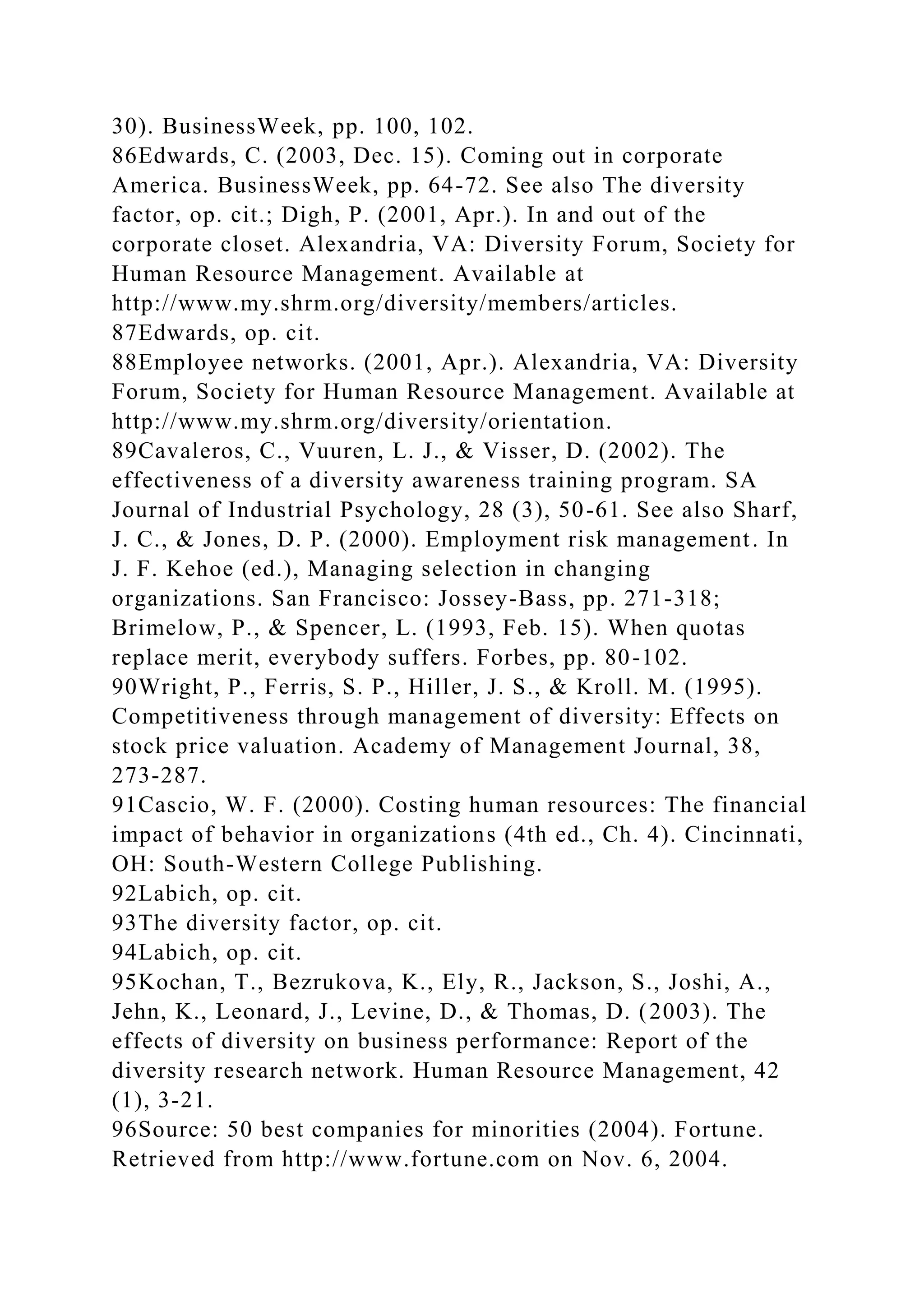

2. Adverse impact (unintentional) discrimination occurs when

identical standards or procedures are applied to everyone,

despite the fact that they lead to a substantial difference in

employment outcomes (e.g., selection, promotion, layoffs) for

the members of a particular group, and they are unrelated to

success on a job. For example, use of a minimum height

requirement of 5 feet 8 inches for police cadets would have an

adverse impact on Asians, Hispanics, and women. The policy is

neutral on its face but has an adverse impact. To use it, an

employer would need to show that the height requirement is

necessary to perform the job.

These two forms of illegal discrimination are illustrated

graphically in Figure 3-1.

Figure 3-1 Major forms of illegal discrimination.

(Source: W. F. Cascio. (2000). Costing human resources: The

financial impact of behavior in organizations [4th ed.], South-

Western College Publishing, Cincinnati, OH, p. 63. Used with

permission.)

THE LEGAL CONTEXT OF HUMAN RESOURCE DECISIONS

Now that we understand the forms that illegal discrimination

can take, let's consider the major federal laws governing

employment. Then we will consider the agencies that enforce

the laws, as well as some important court cases that have

interpreted them. The federal laws that we will discuss fall into

two broad classes:

1. Laws of broad scope that prohibit unfair discrimination.

2. Laws of limited application, for example, those that require

nondiscrimination as a condition for receiving federal funds

(contracts, grants, revenue-sharing entitlements).

The particular laws that we shall discuss within each category

are the following:](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/diversityatworkquestionsthischapterwillhelpmanagersanswe-221026032732-01cc7112/75/Diversity-at-WorkQuestions-This-Chapter-Will-Help-Managers-Answe-docx-60-2048.jpg)

![also Janove, J. W. (2003, March). Skating through the

minefield. HRMagazine, pp. 107-113.

32Campbell, W. J., & Reilly, M. E. (2000). Accommodations

for persons with disabilities. In J. F. Kehoe (ed.), Managing

selection in changing organizations, pp. 319-367. San

Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

33Cascio, W. F. (1994). The 1991 Civil Rights Act and the

Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990: Requirements for

psychological practice in the workplace. In B. D. Sales & G. R.

VandenBos (eds.), Psychology in litigation and legislation, pp.

175-211. Washington, DC: American Psychological

Association.

34Petesch, P. J. (2000, Nov.). Popping the disability-related

question. HRMagazine, pp. 161-172.

35Wells, S. J. (2001a, April). Is the ADA working?

HRMagazine, pp. 38-46.

36Kolstad v. American Dental Association, 119 S. Ct. 2118

(1999).

37Paltell, E. (1999, Sept.). FMLA: After six years, a bit more

clarity. HRMagazine, pp. 144-150.

38Davis, G. M. (2003, Aug. 22). The Family and Medical Leave

Act: 10 years later.

http://www.shrm.org/hrresources/lrpt_published/CMS_005127.a

sp.

39Shea, R. E. (2000, Jan.). The dirty dozen. HRMagazine, pp.

52-56.

40Most small businesses appear prepared to cope with new

family-leave rules. (1993, Feb. 8). The Wall Street Journal, pp.

B1, B2.

41Clark, M. M. (2003). FMLA 10th anniversary events focus on

workplace flexibility options. HRMagazine, pp. 30, 42.

42Jackson, D. J. (1978). Update on handicapped discrimination.

Personnel Journal, 57, 488-491.

43Garcia, L. M. (2003). USERRA awakens: Complying with the

newest military leave law. Retrieved from the World Wide Web

at [email protected] on May 29, 2003.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/diversityatworkquestionsthischapterwillhelpmanagersanswe-221026032732-01cc7112/75/Diversity-at-WorkQuestions-This-Chapter-Will-Help-Managers-Answe-docx-107-2048.jpg)

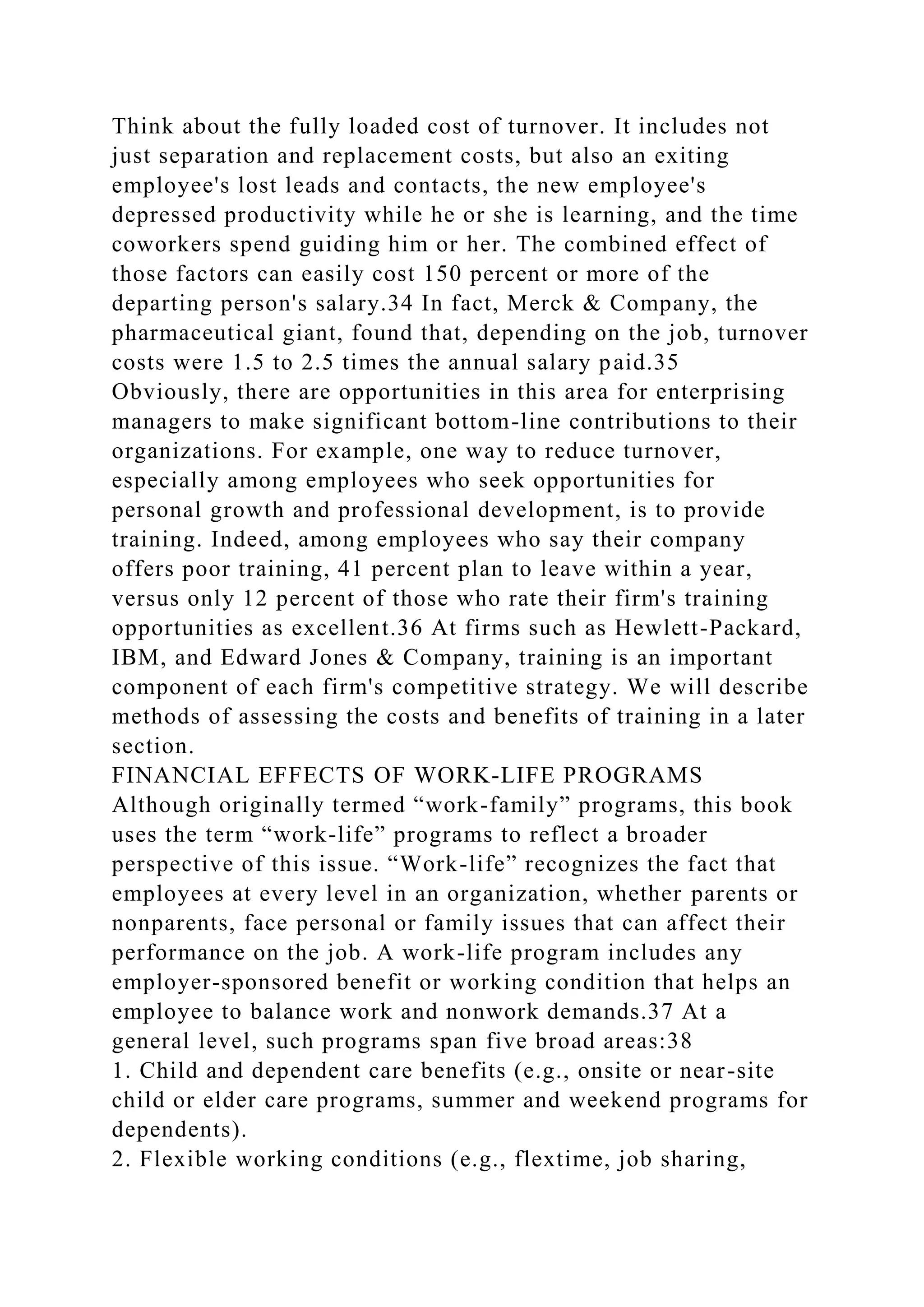

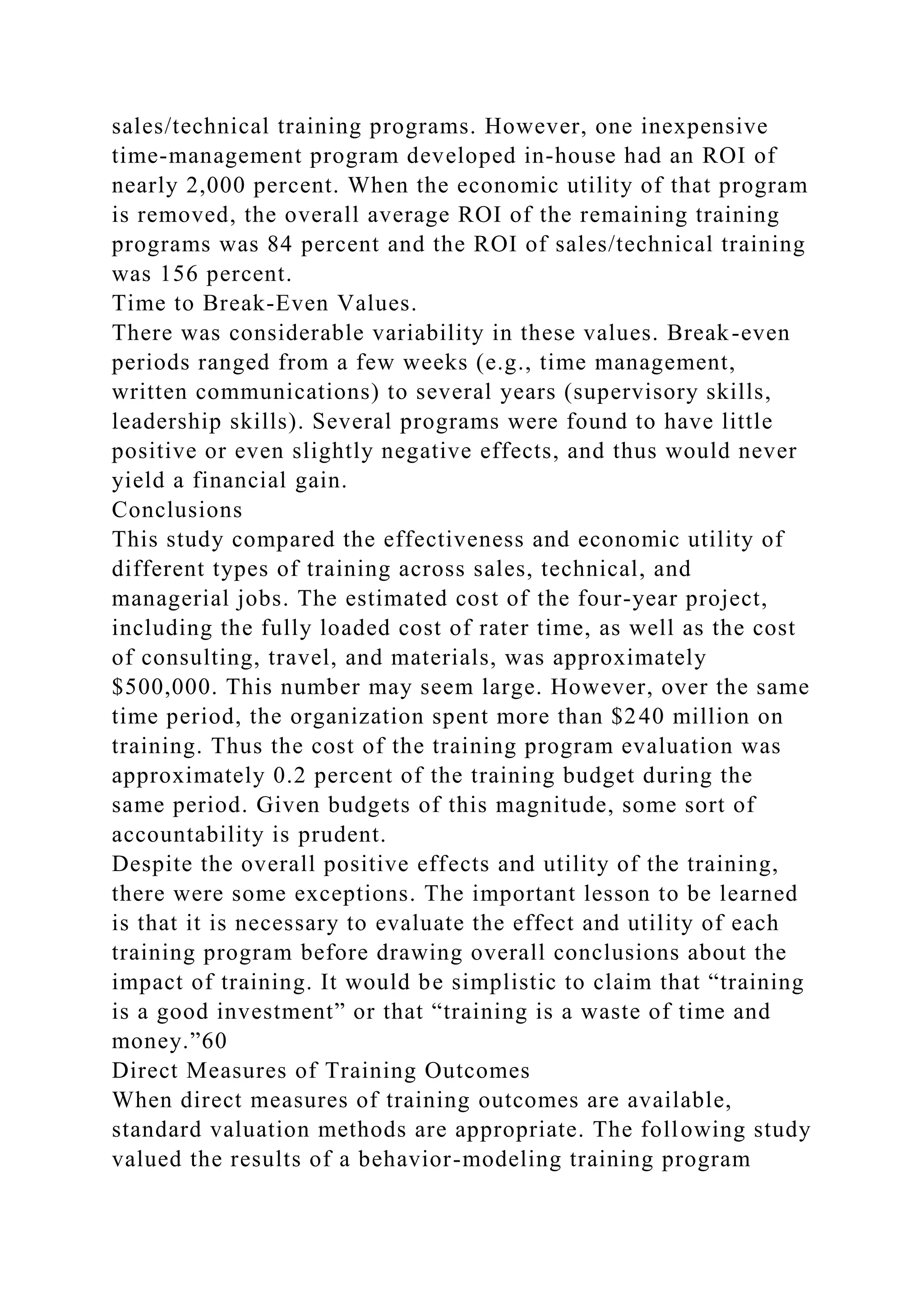

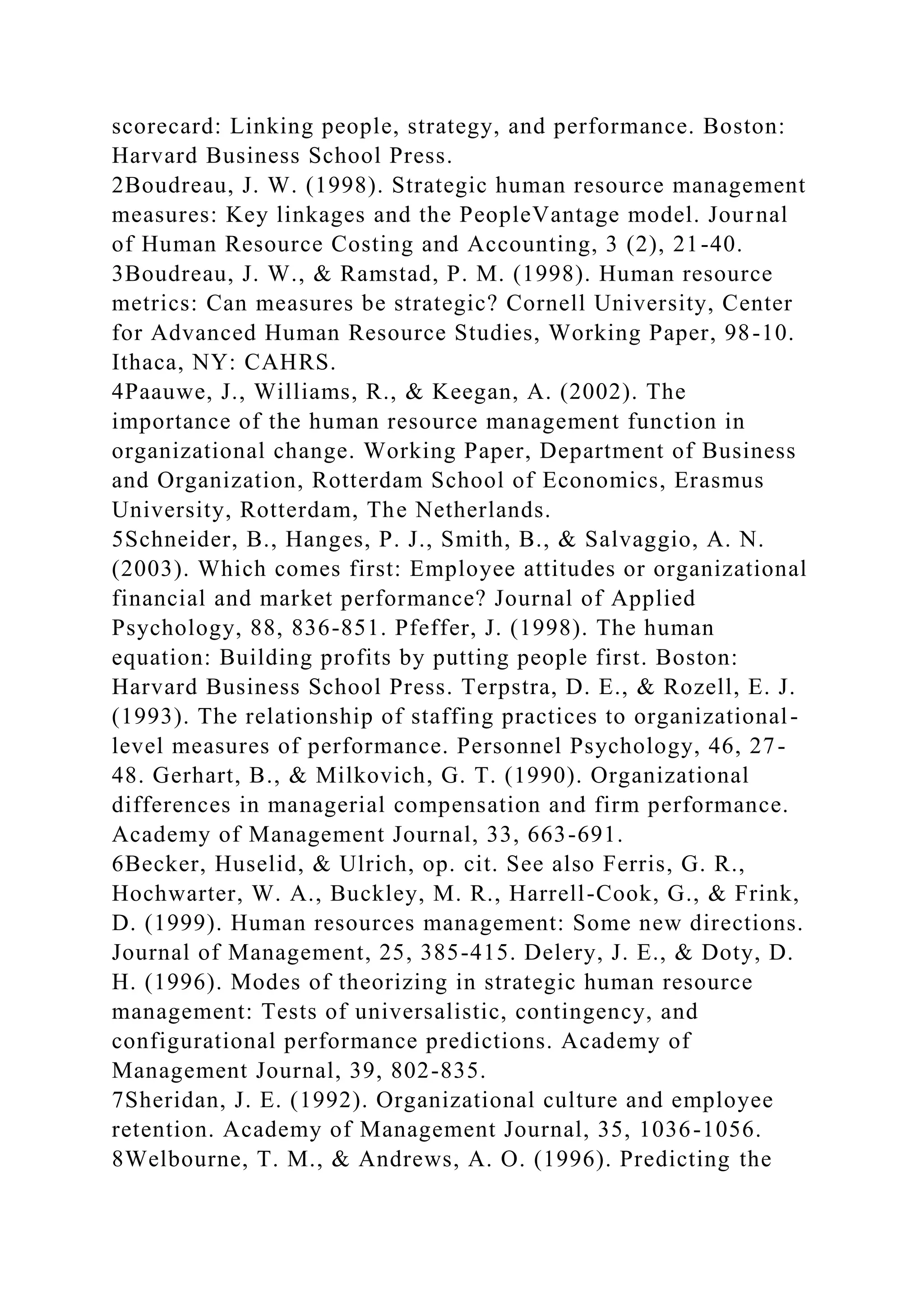

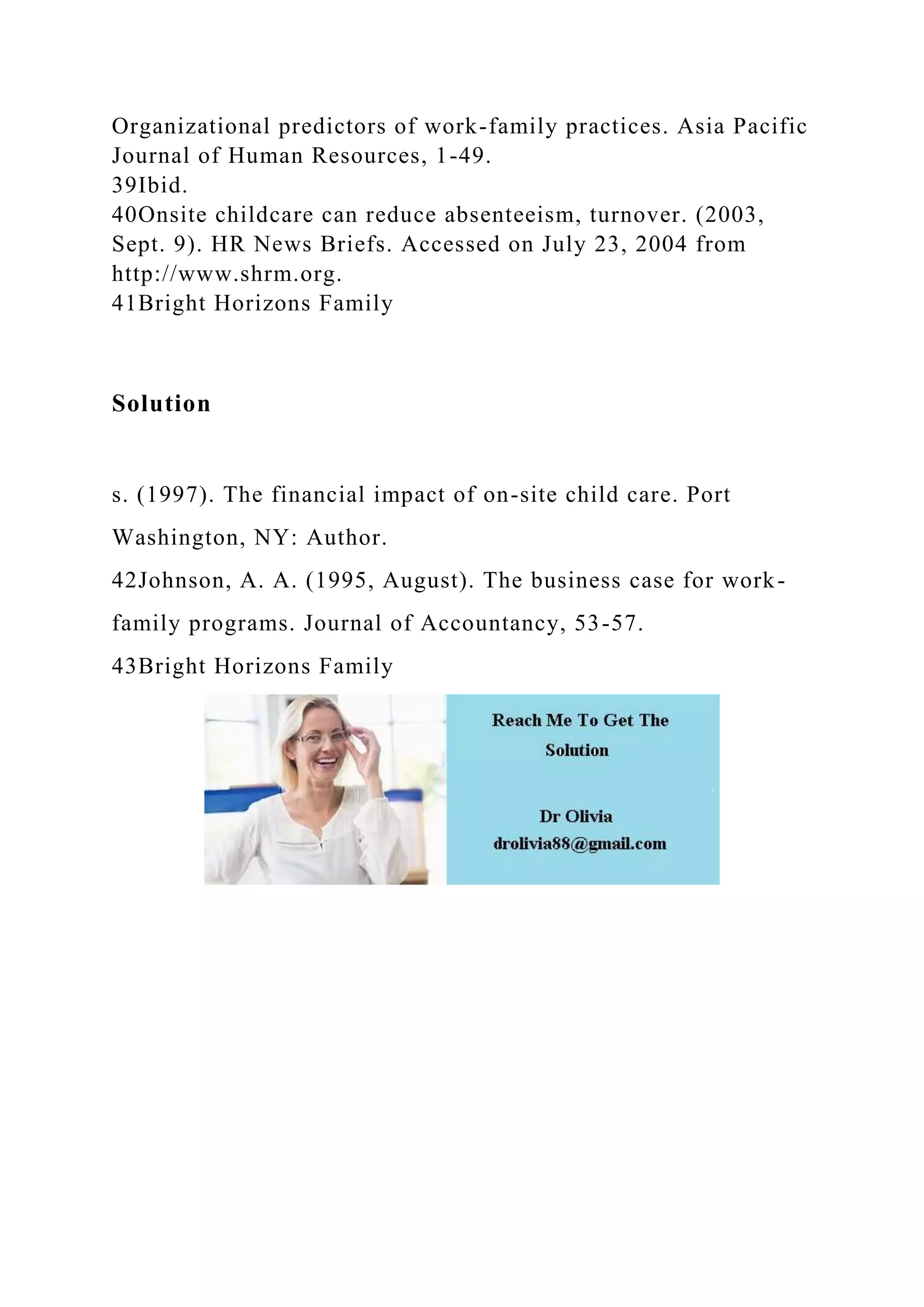

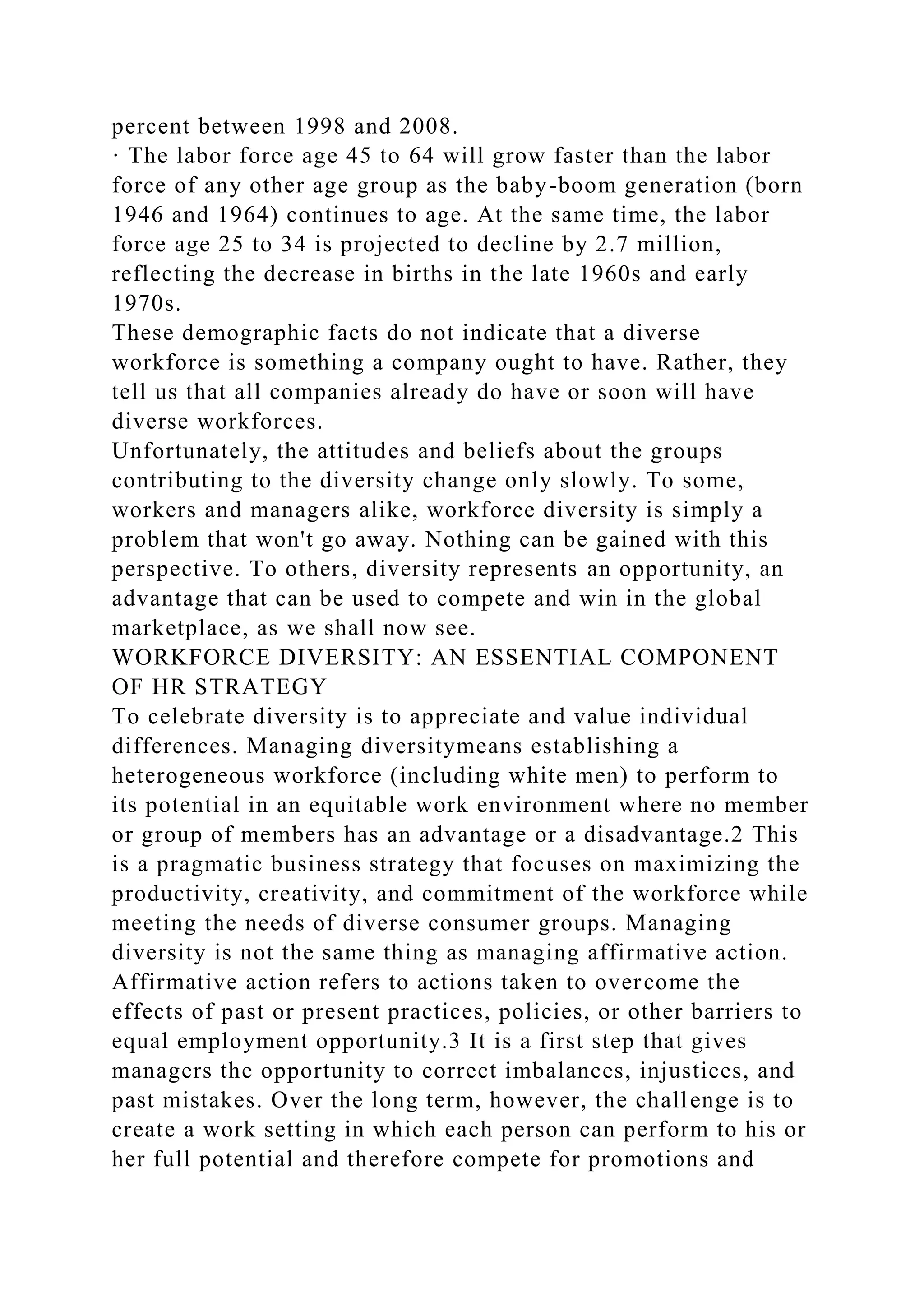

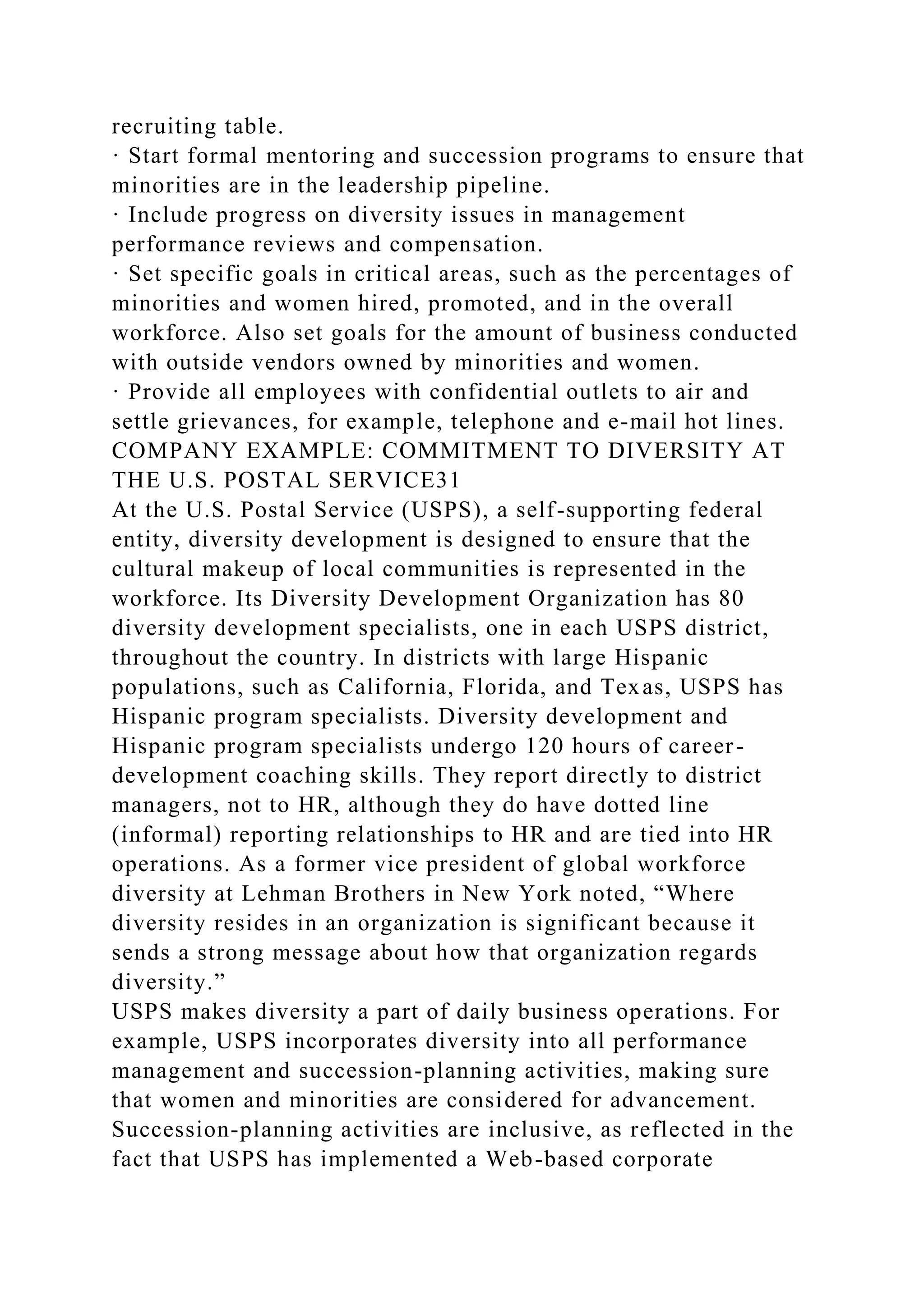

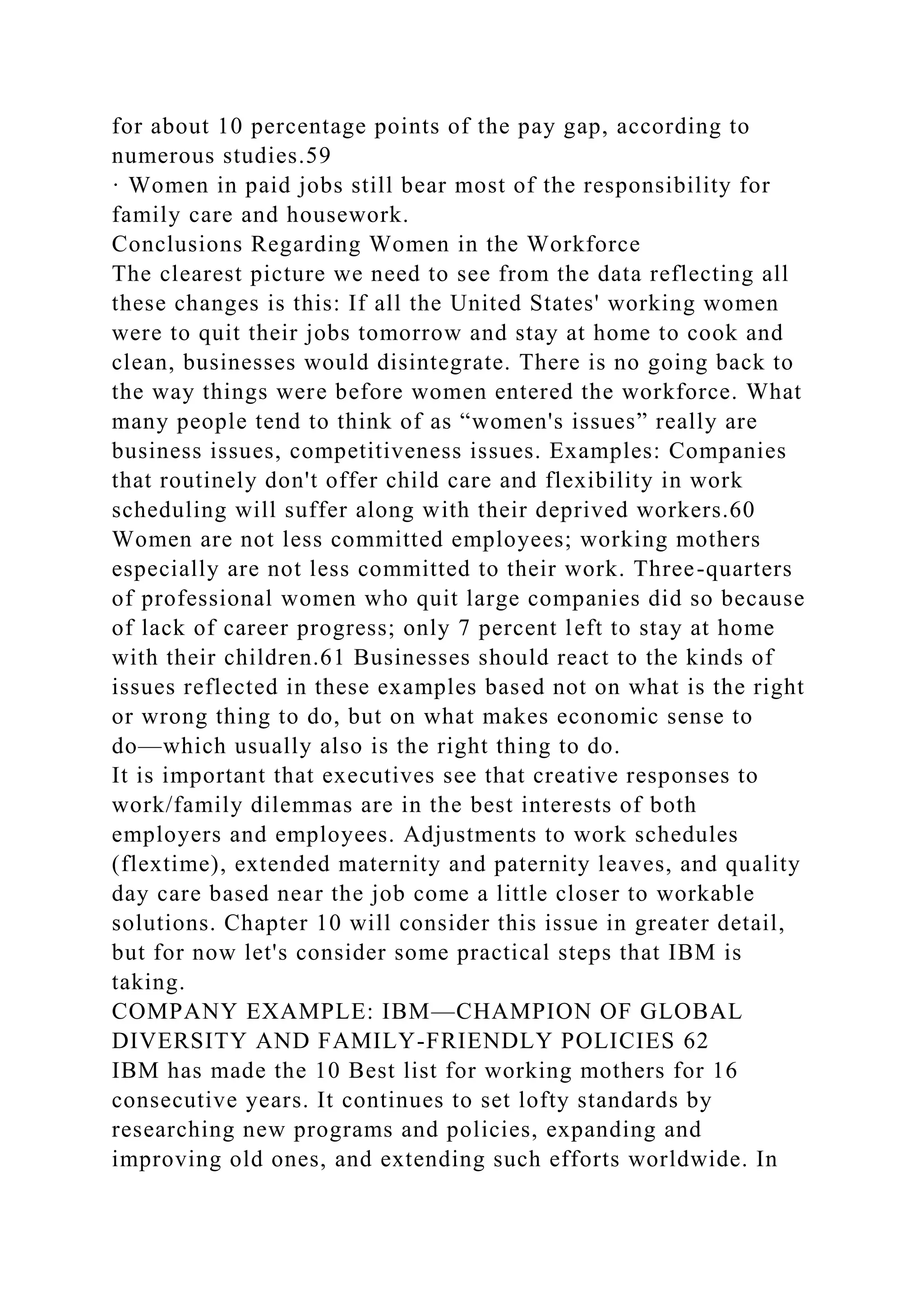

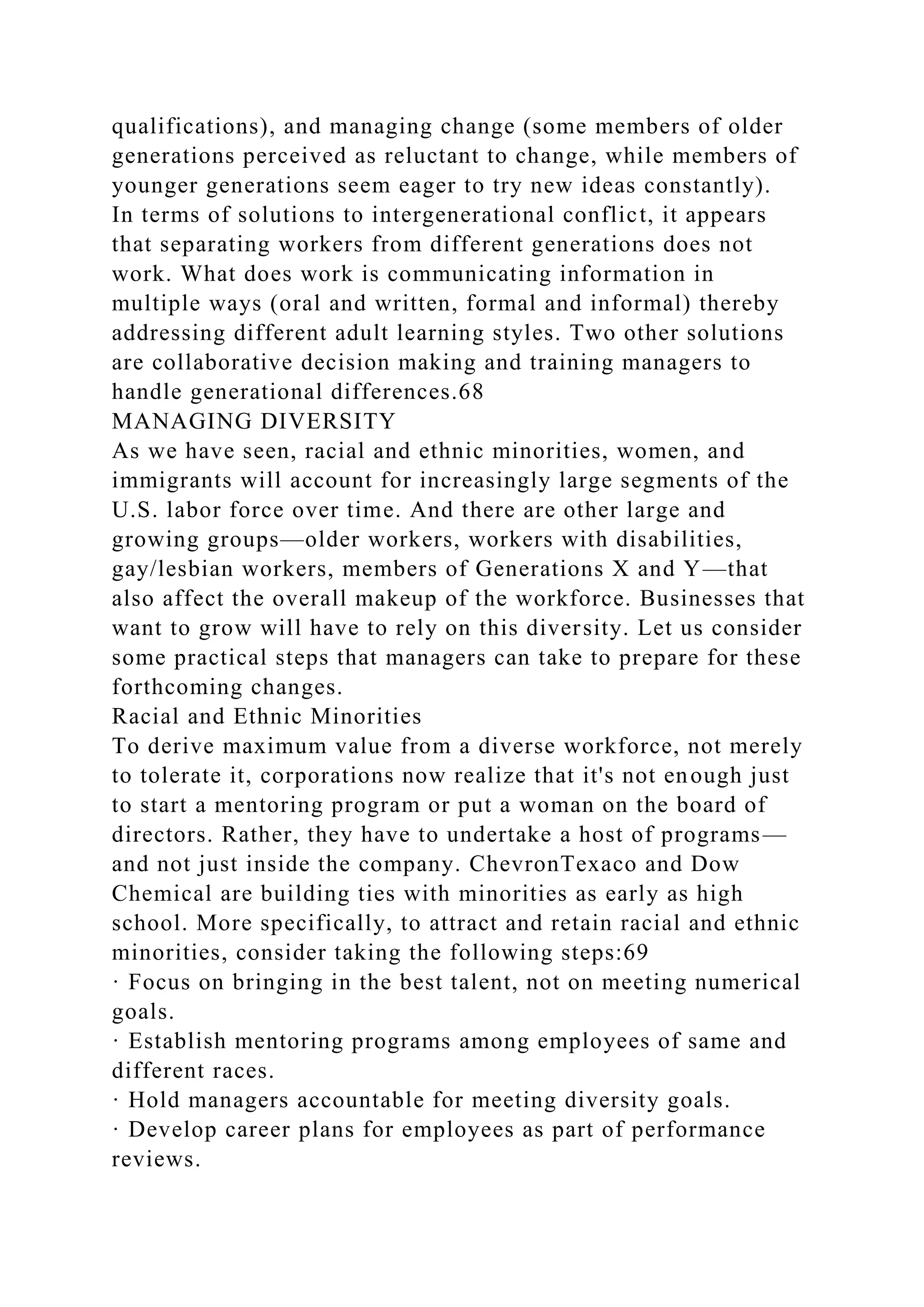

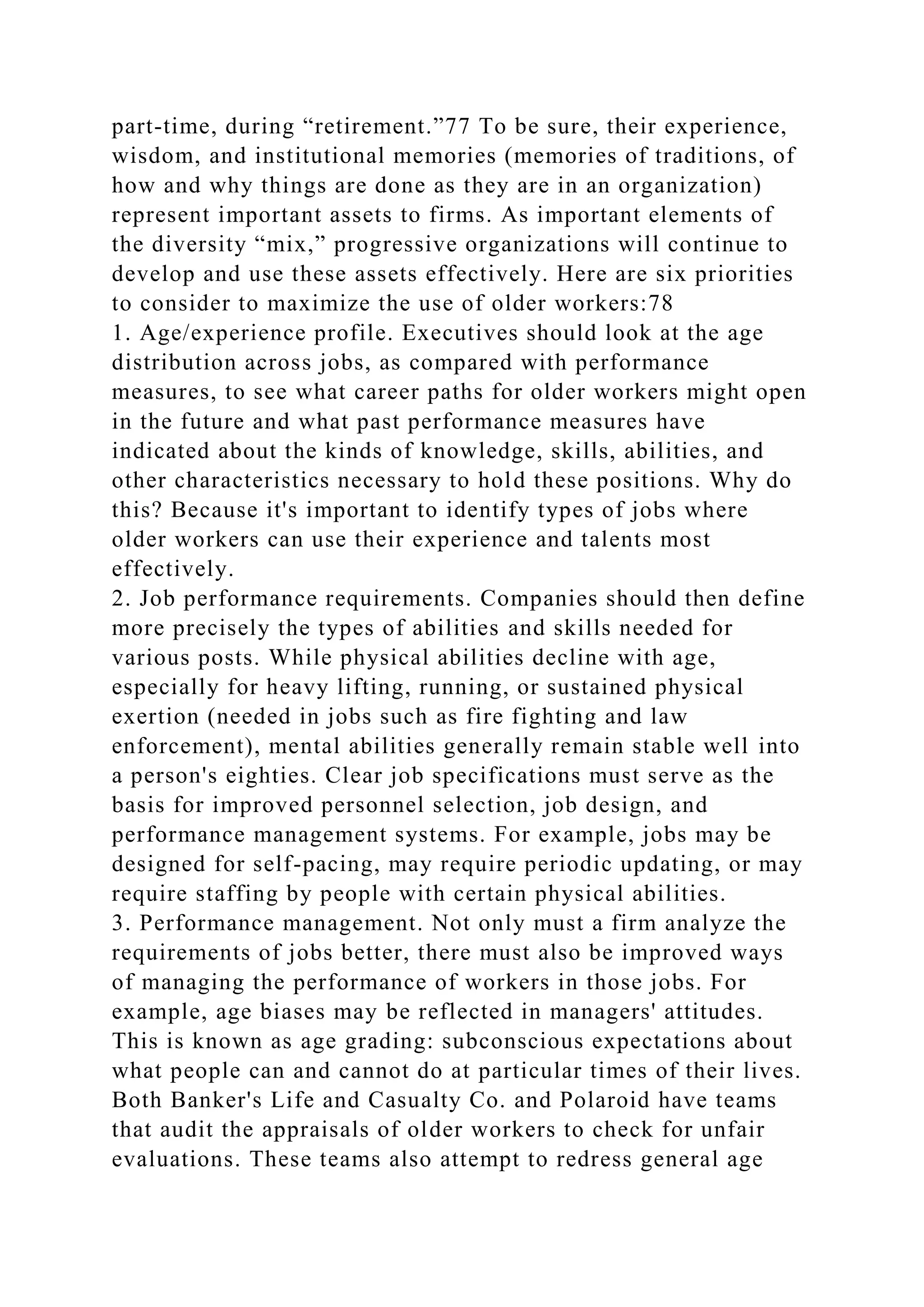

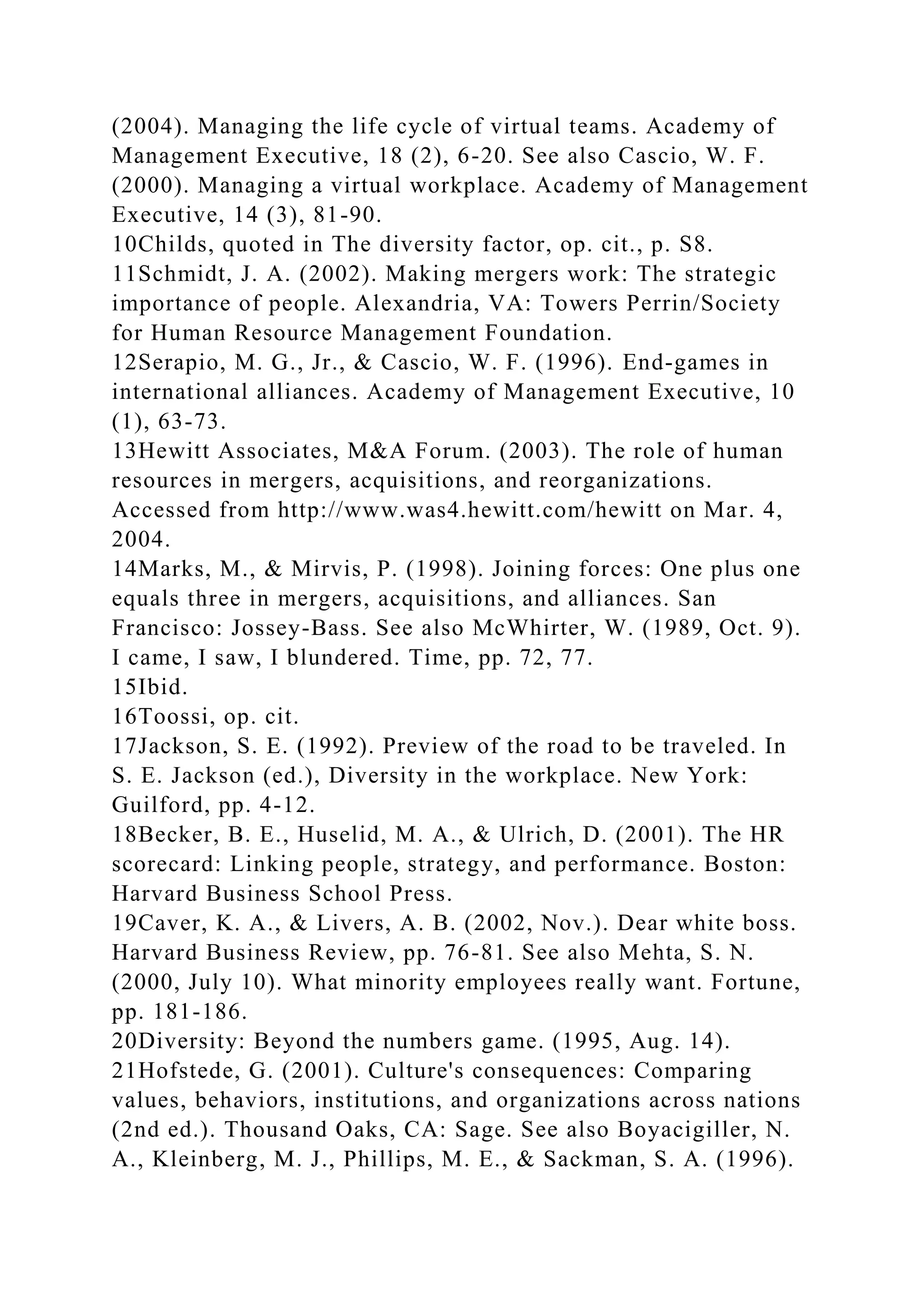

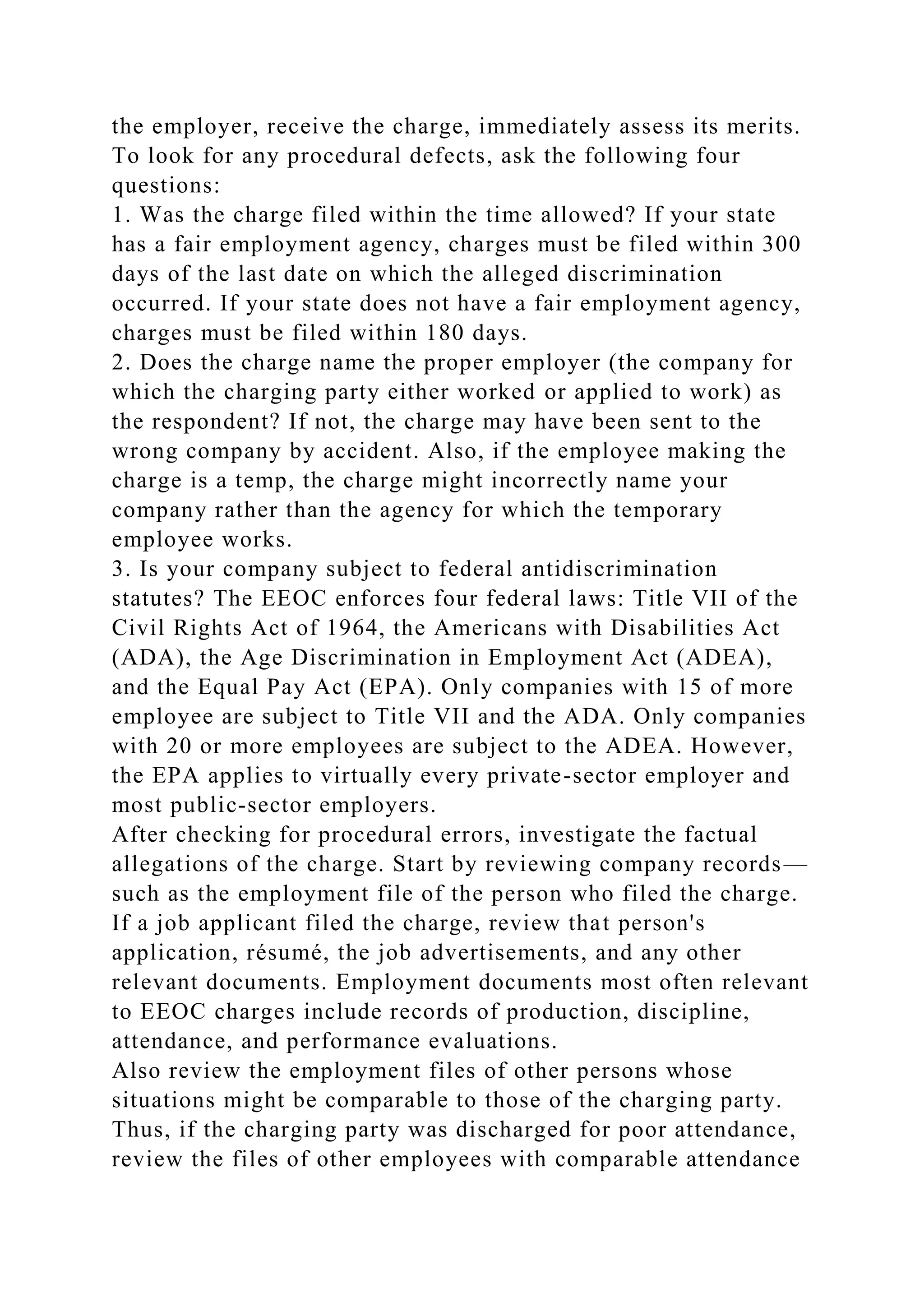

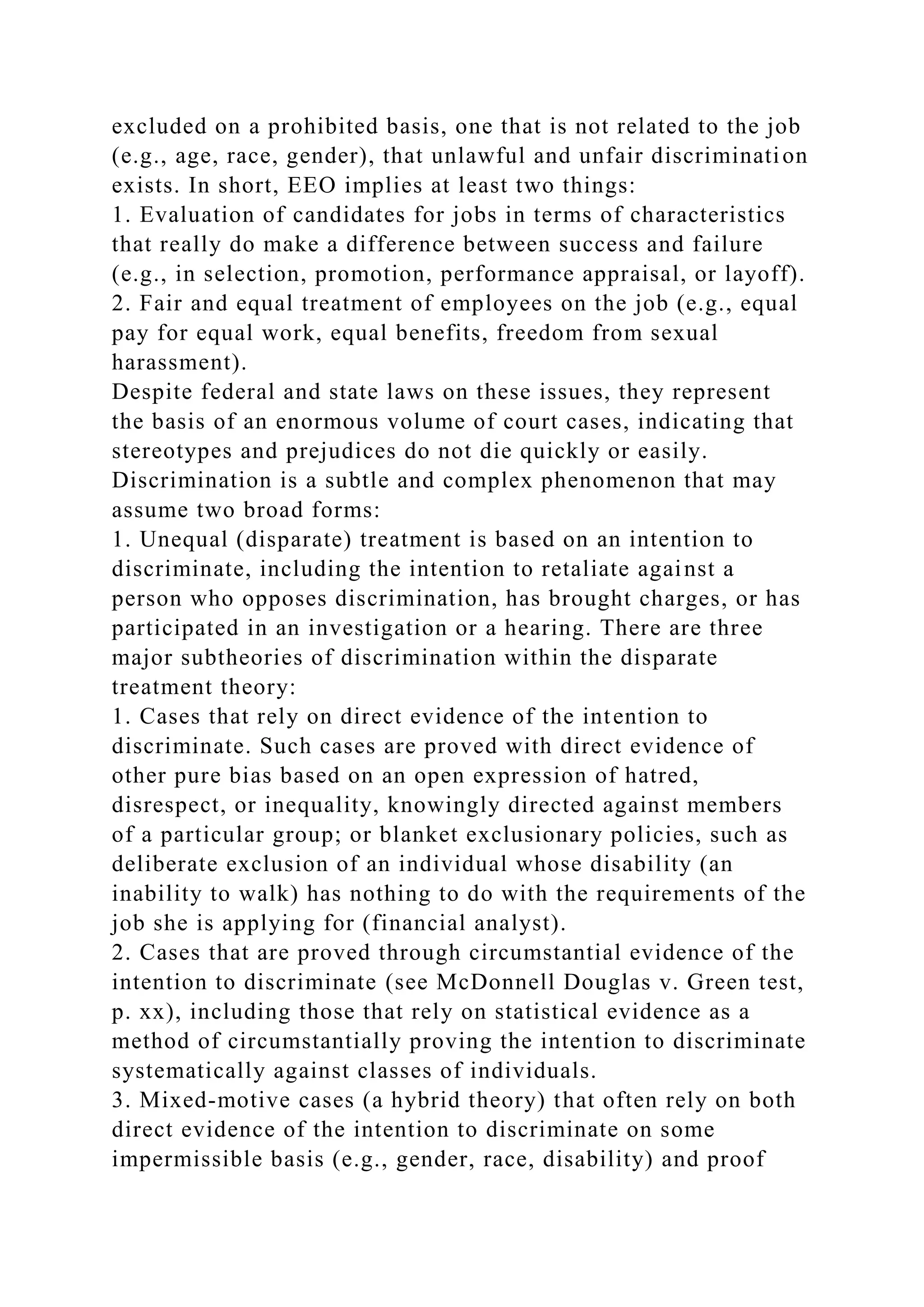

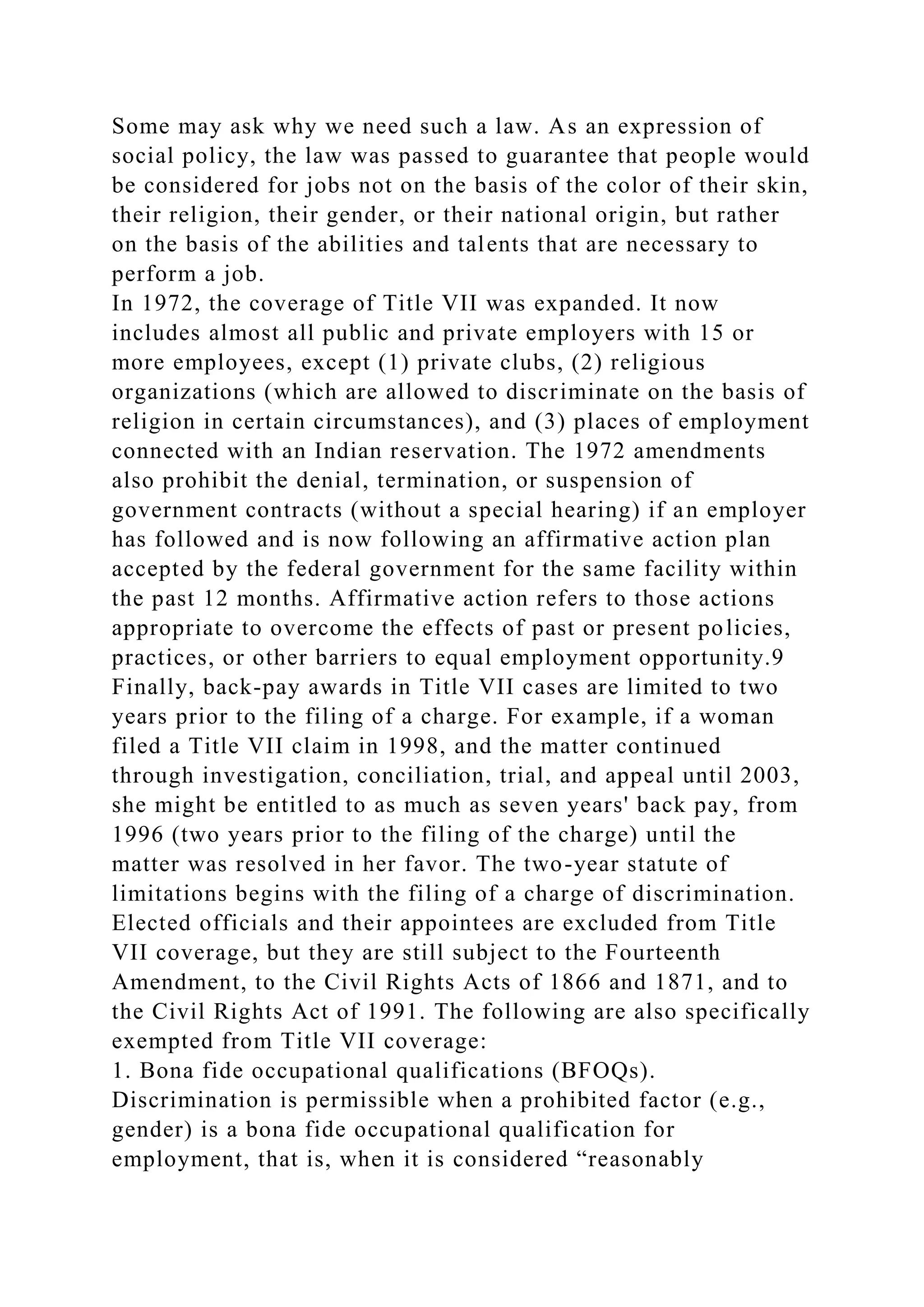

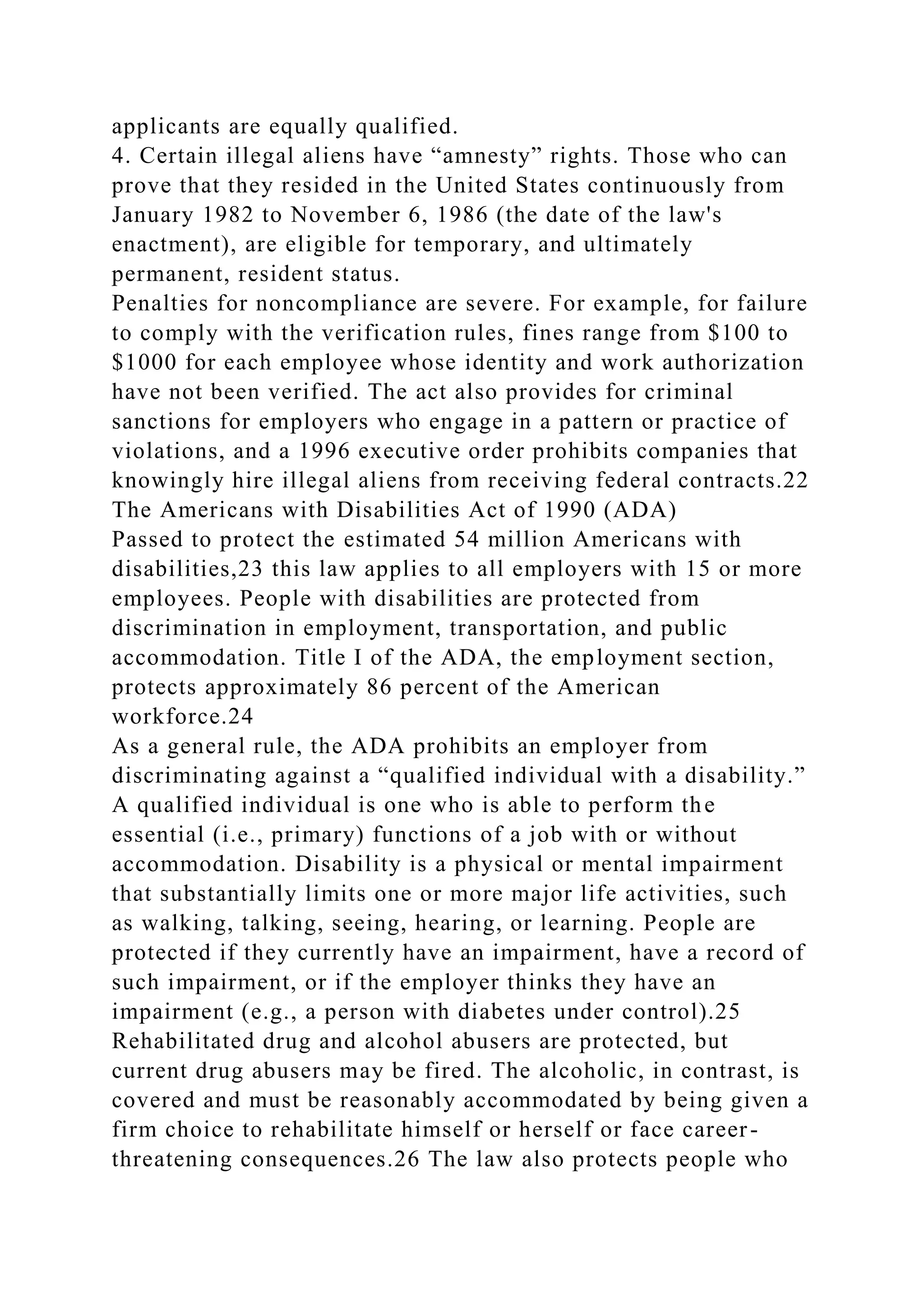

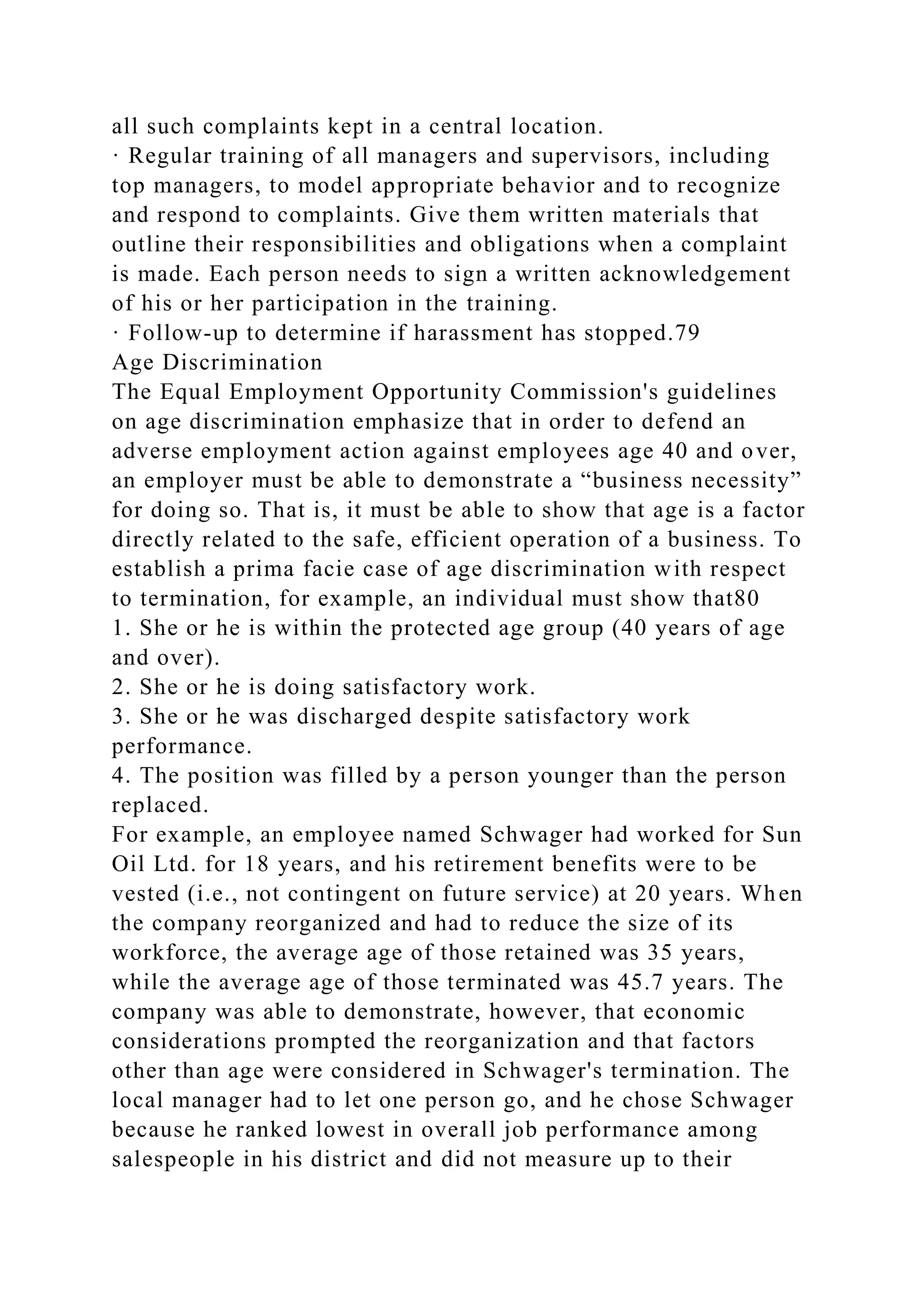

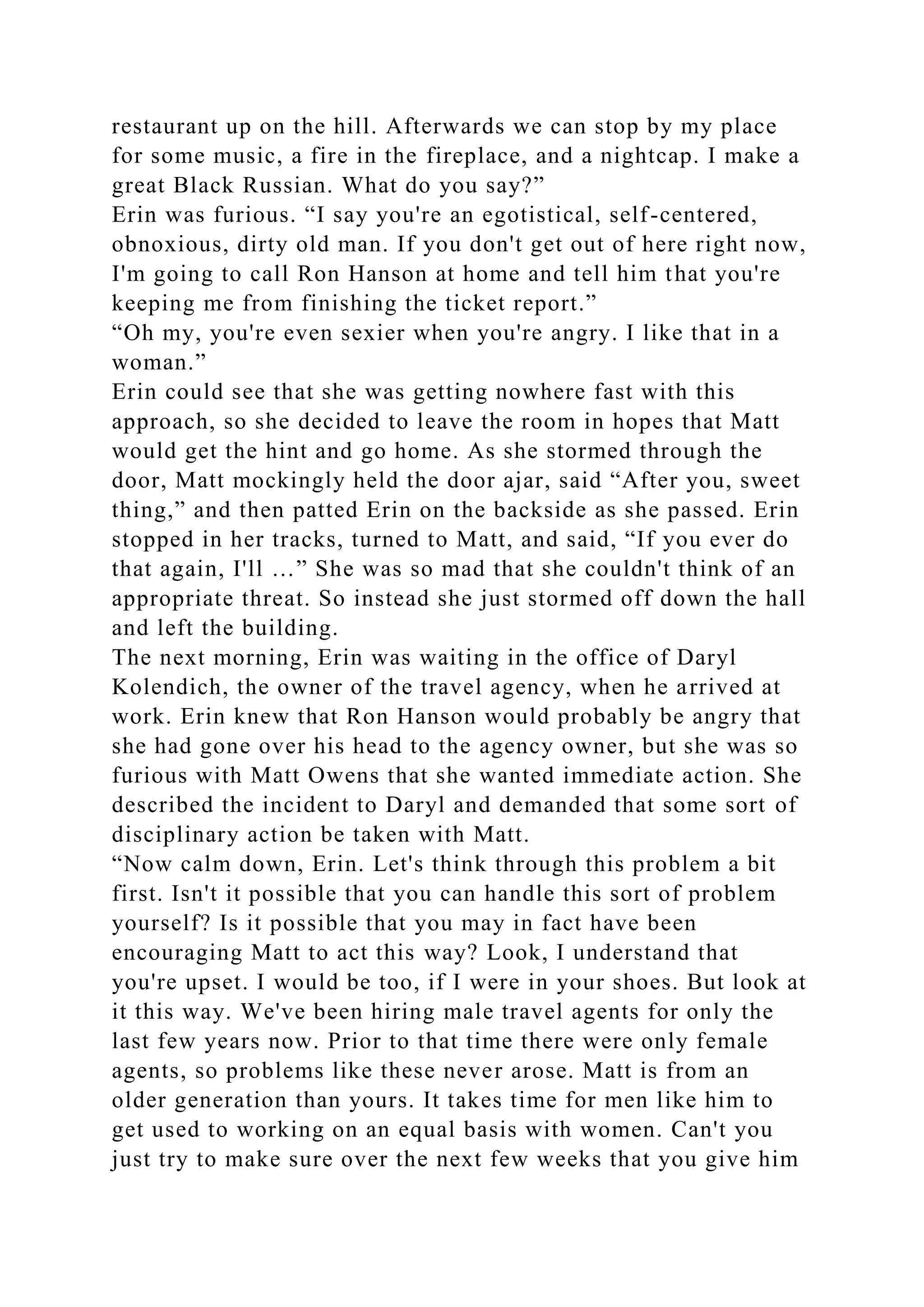

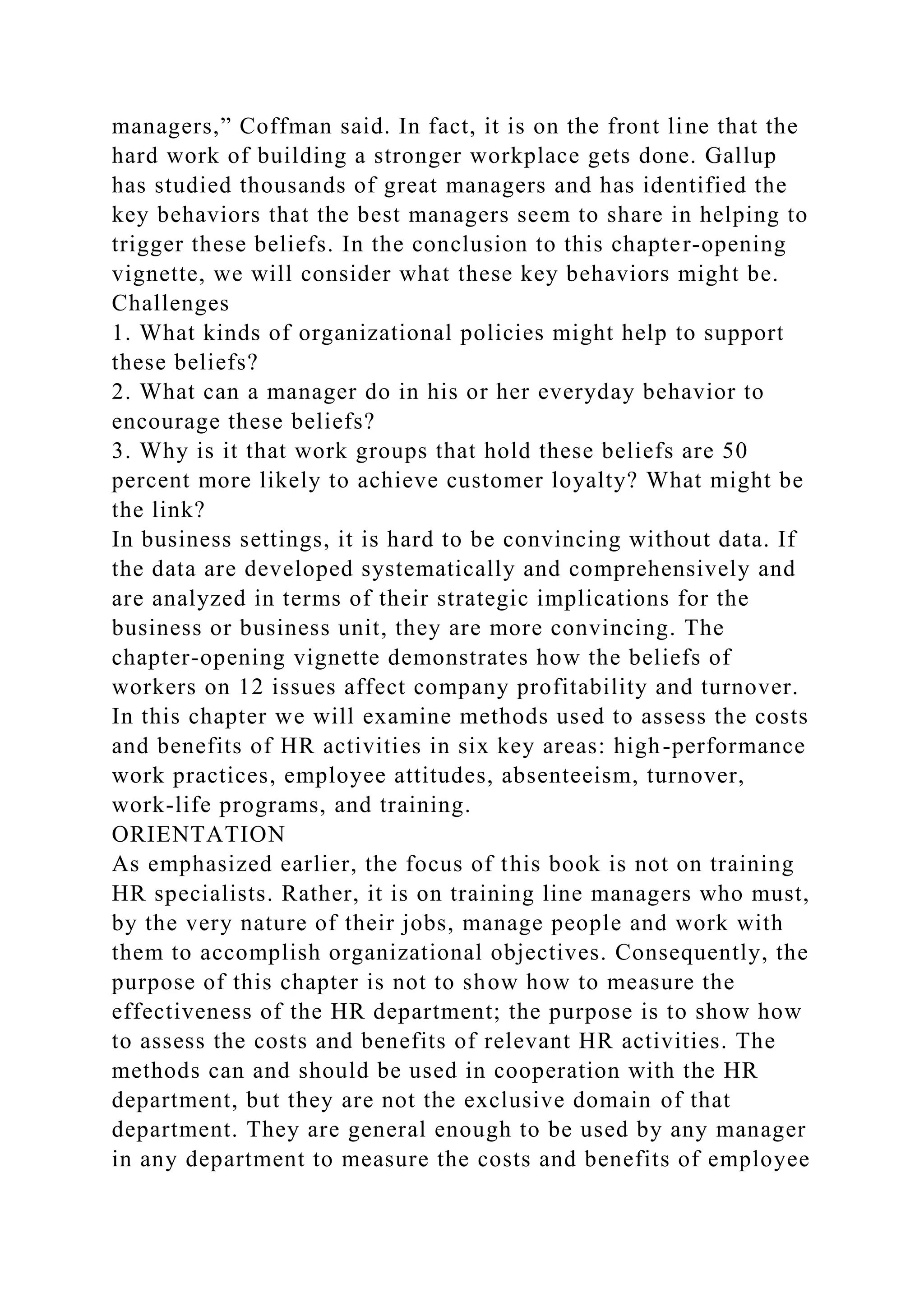

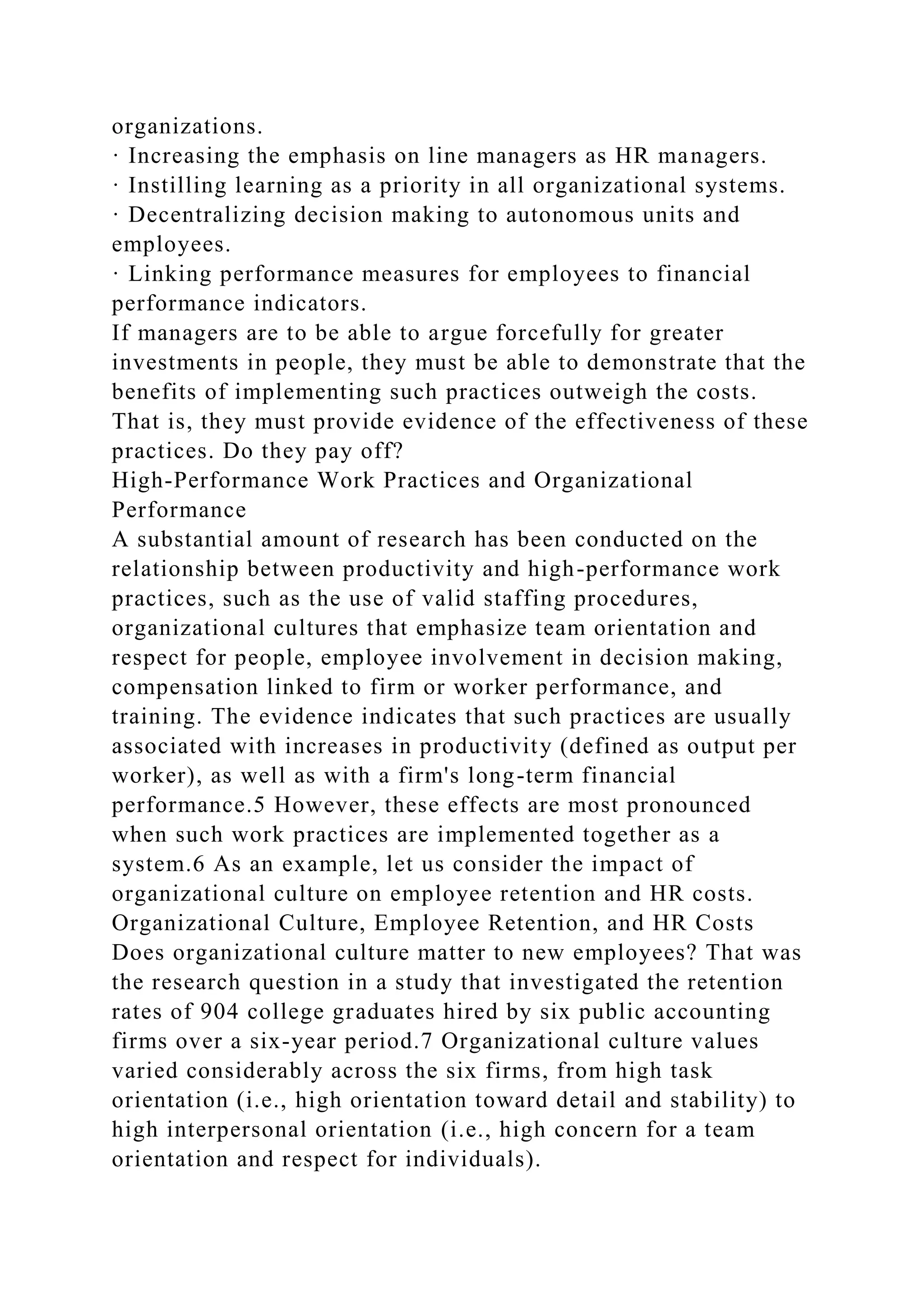

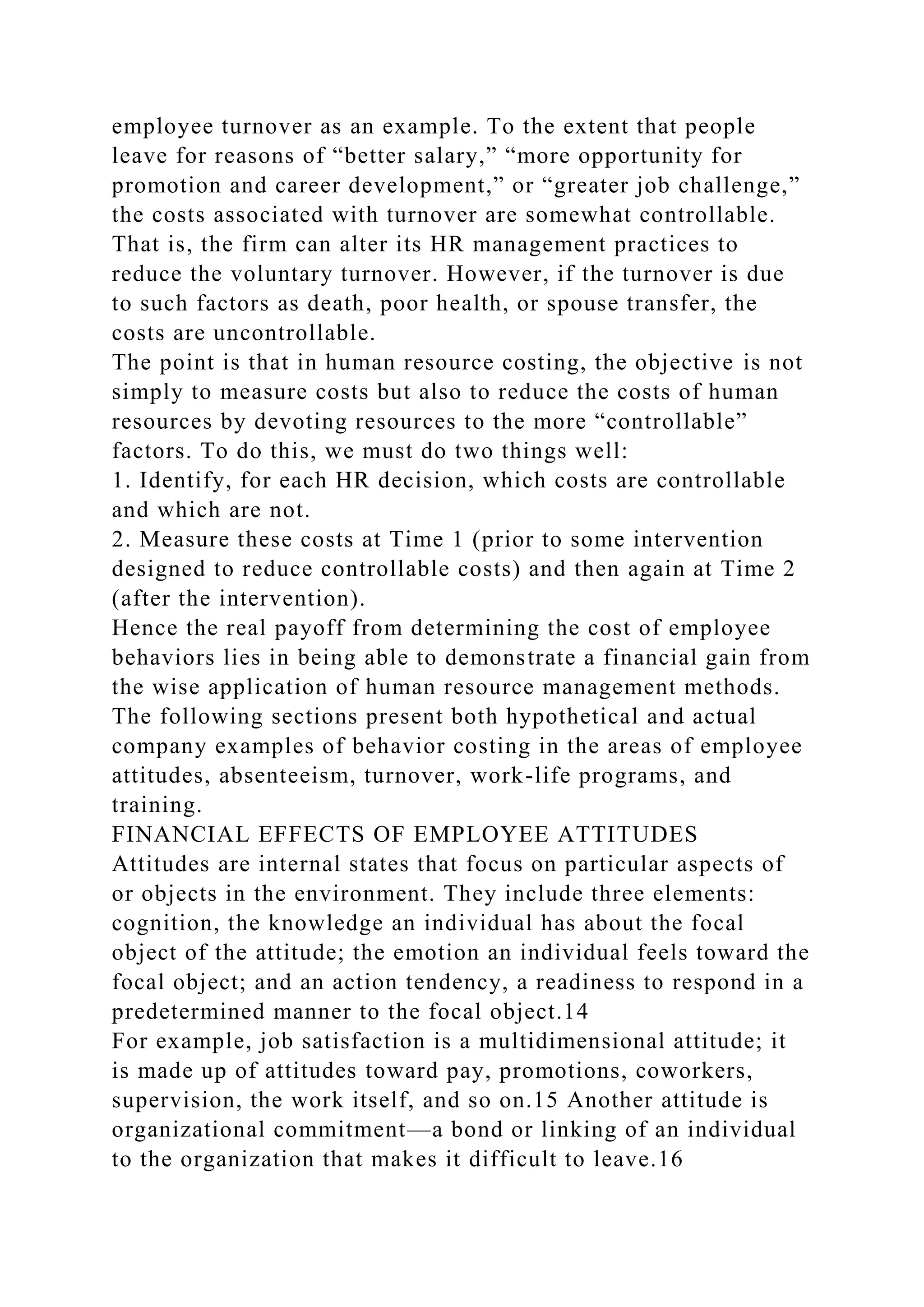

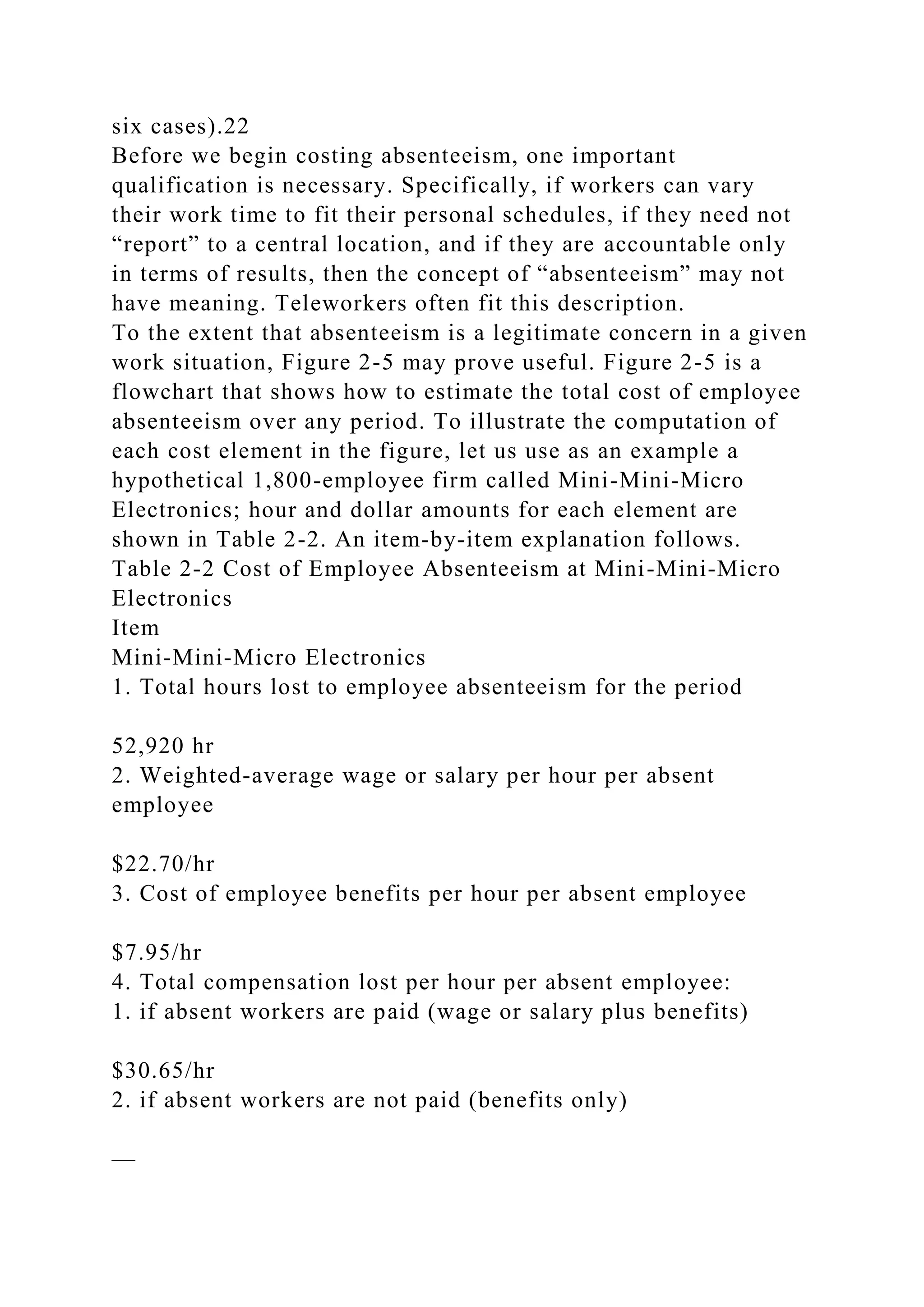

![New employees stayed an average of 45 months in the cultures

emphasizing interpersonal relationships, but only 31 months in

the cultures emphasizing work task values (see Figure 2-1).

This is a 14-month difference in median survival time. The next

task was to translate the difference in time into a measure of

profits forgone (i.e., opportunity losses).

Figure 2-1 Voluntary survival rates in two organizational

cultures.

(Source: J. E. Sheridan. (1992). Organizational culture and

employee retention, Academy of Management Journal, 35, p.

1049.)

Using the firms' average billing fees, along with hiring,

training, and compensation costs, means profits per professional

employee ranged from $58,000 during the first year of

employment to $67,000 during the second year and $105,000

during the third. A firm therefore incurs an opportunity loss of

only $9,000 ($67,000 $58,000) when a new employee replaces a

two-year employee, but a $47,000 loss ($105,000 $58,000)

when a new employee replaces a three-year employee.

If we assume that both strong and weak performers generated

the same average level of profits in each year of employment

and that annual profits were distributed uniformly between

those with 31 and those with 45 months' seniority, it is possible

to estimate the opportunity loss associated with the 14-month

difference in median survival time. This difference translated

into an opportunity loss of approximately $44,000 per new

employee [($47,000 $9,000/12) 14] between the firms having

the two different types of cultural values. That's roughly

$62,000 per new employee in 2004 dollars. Considering the

total number of new employees hired by each office over the

six-year period of the study, the study indicates that a firm

emphasizing work task values incurred opportunity losses of

approximately $6 to $9 million ($8.5 to $12.8 million in 2004](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/diversityatworkquestionsthischapterwillhelpmanagersanswe-221026032732-01cc7112/75/Diversity-at-WorkQuestions-This-Chapter-Will-Help-Managers-Answe-docx-120-2048.jpg)

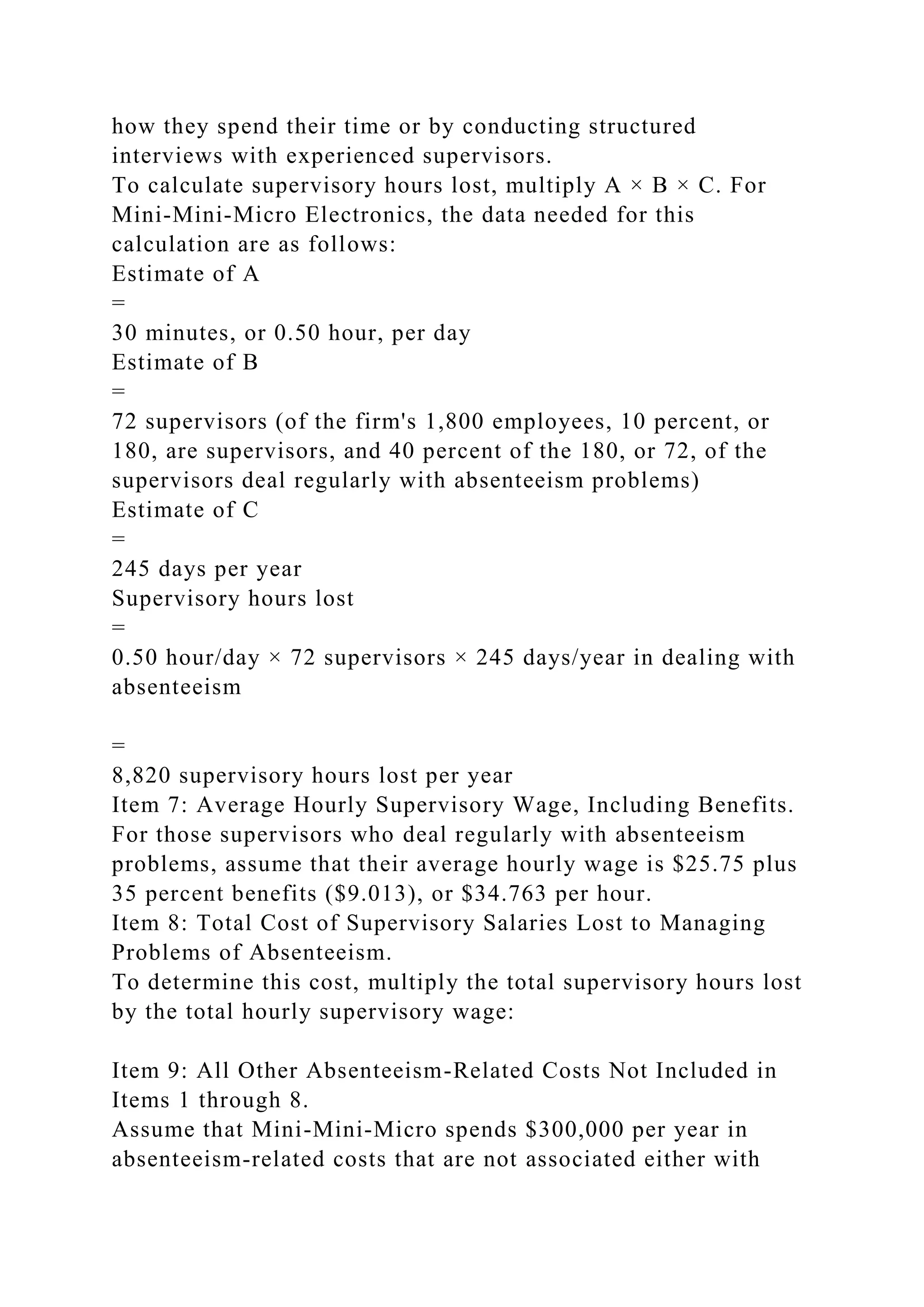

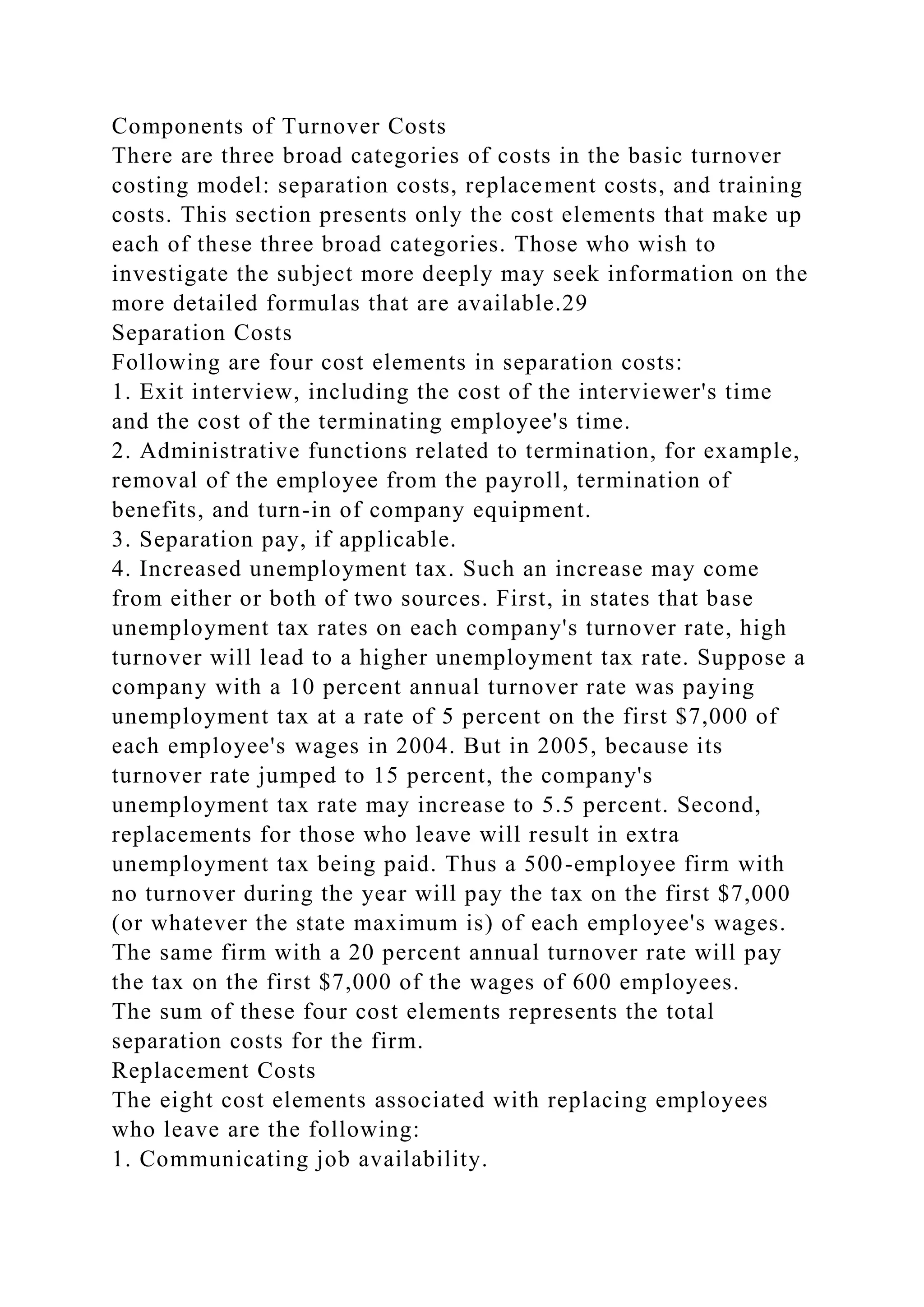

![5. Total compensation lost to absent employees (total hours lost

× 4a or 4b, whichever applies)

$1,621,998

6. Total supervisory hours lost on employee absenteeism

8,820 hr

7. Average hourly supervisory wage, including benefits

$34.763/hr

8. Total supervisory salaries lost to managing problems of

absenteeism (hours lost × average hourly supervisory wage—

item 6 × item 7)

$306,605.25

9. All costs incidental to absenteeism and not included in items

1 through 8

$300,000

10. Total estimated cost of absenteeism—summation of items 5,

8, and 9

$2,228,603.25

11. Total estimated cost of absenteeism per employee (total

estimated costs ÷ total number of employees)

$1,238.11 per employee absence

Figure 2-5 Total estimated cost of employee absenteeism.

(Source: W. F. Cascio. (2000). Costing human resources: The

financial impact of behavior in organizations [4th ed.], South-

Western College Publishing, Cincinnati, OH, p. 63. Used with

permission.)

Item 1: Total Hours Lost.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/diversityatworkquestionsthischapterwillhelpmanagersanswe-221026032732-01cc7112/75/Diversity-at-WorkQuestions-This-Chapter-Will-Help-Managers-Answe-docx-131-2048.jpg)