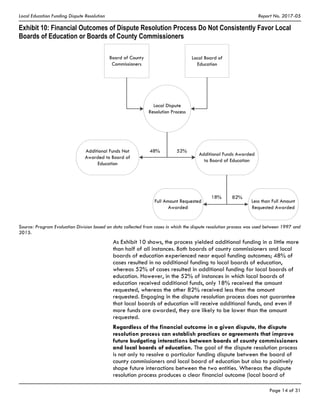

North Carolina's process for resolving disputes between local boards of education and county commissioners over K-12 education funding is generally effective and economical, though litigation is an unnecessary aspect. The process is used infrequently and seldom reaches litigation, but when used, outcomes do not consistently favor either party and may improve future budgeting. However, litigation is costly and time-consuming. Tennessee avoids litigation through default funding, whereas North Carolina's process allows litigation. Additionally, local boards maintain unnecessary fund balances given their operational funding sources. The General Assembly could eliminate litigation by revising the law to include default funding, and direct study of appropriate fund balance levels.