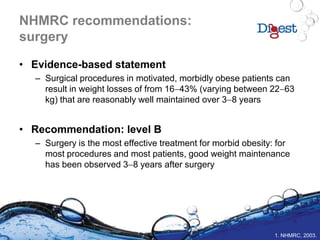

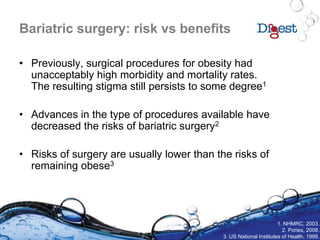

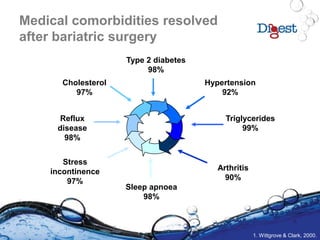

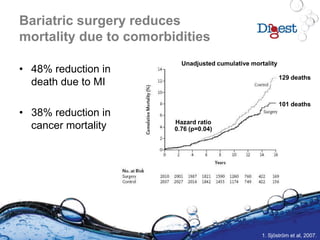

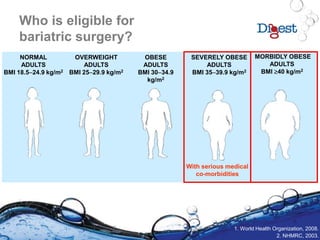

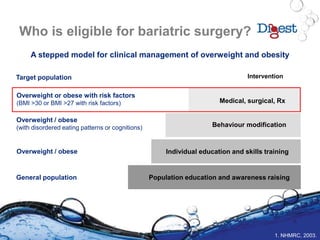

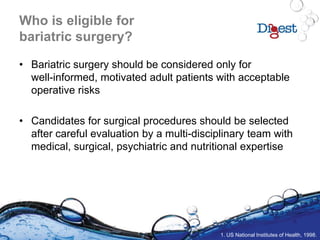

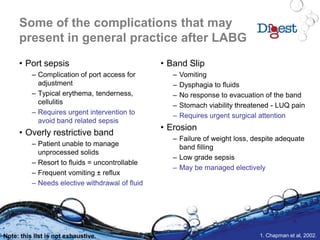

This document discusses bariatric surgery, focusing on its necessity for morbidly obese patients with serious comorbidities, the types of surgical procedures available, and their associated risks and benefits. It highlights the importance of multidisciplinary care in managing obesity and the significant health improvements observed after surgery, including substantial weight loss and resolution of comorbidities. The document emphasizes a careful selection process for surgical candidates and the necessity for long-term follow-up and lifestyle changes post-surgery.

![References

1. Access Economics, 2008. The growing cost of obesity in 2008: three years on. Available at:

http://www.accesseconomics.com.au/publicationsreports/getreport.php?report=102&id=139. Accessed January 2009.

2. Access Economics, 2006. The economic costs of obesity. Available at:

http://www.accesseconomics.com.au/publicationsreports/getreport.php?report=102&id=139. Accessed January 2009.

3. Chapman A et al. Systematic review of laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding for the treatment of obesity : Update and re-

appraisal. ASERNIP-S Report No. 31, Second Edition. Adelaide, South Australia: ASERNIP-S, June 2002.

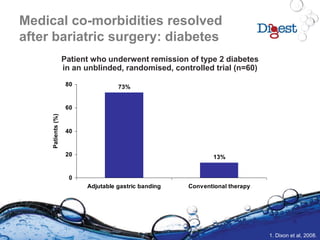

4. Dixon JB et al. JAMA 2008;299:316-23.

5. Dixon JB. Obes Surg 2008 Nov 13. [Epub ahead of print].

6. Lee CM, Cirangle PT, Jossart GH. Surg Endosc 2007;21:1810-6.

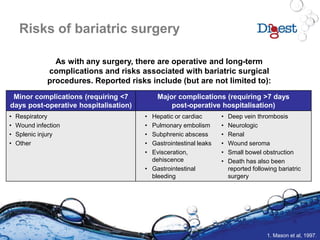

7. Mason EE et al. Obes Surg 1997;7:189-97.

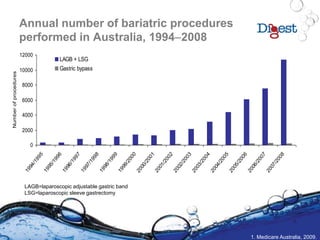

8. Medicare Australia. Available at: https://www.medicareaustralia.gov.au/statistics/mbs_item.shtml. Accessed February 2009.

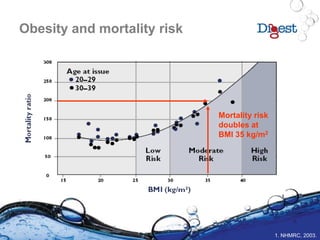

9. National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC), 2003. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of overweight

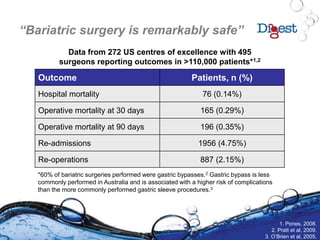

and obesity in adults. Available at: http://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/obesityguidelines-guidelines-

adults.htm. Accessed January 2009.

10. O’Brien PE, Brown WA, Dixon JB. Med J Aust 2005;183:310–4.

11. Obesity Surgery Society of Australia and New Zealand, 2008. Available at: http://www.ossanz.com.au/lapband.asp. Accessed

January 2009.

12. Pories WJ. Ann Surg 1995;222:339-50.

13. Pories WJ. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2008;95:S89-S96.

14. Pratt GM et al. Surg Endosc 2009 Jan 30. [Epub ahead of print].

15. Sabin J et al. Obes Res 2005;13:250-3.

16. Sjöström L et al. N Engl J Med 2007;357:741-52.

17. US National Institutes of Health. Clinical Guidelines on the Identification, Evaluation, and Treatment of Obesity in Adults: The

Evidence Report. NHLBI Obesity Education Initiative. Expert Panel on the Identification, Evaluation, and Treatment of Obesity in

Adults. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 1998. Available at:

http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/guidelines/obesity/ob_gdlns.pdf. Accessed February 2009.

18. US National Institutes of Health. Expert Panel on the Identification, Evaluation, and Treatment of Overweight in Adults. Am J Clin

Nutr 1998;68:899–917.

19. Wittgrove AC, Clark GW. Obes Surg 2000;10:233-9.

20. World Health Organization, Global database on Body Mass Index. Available at: http://www.who.int/bmi/index.jsp. Accessed

January 2009.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/digestbariatric2009-150106224315-conversion-gate02/85/Developments-In-Gastrointestinal-Therapies-59-320.jpg)