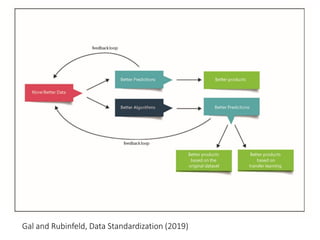

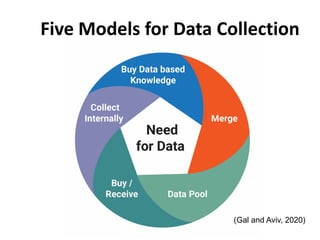

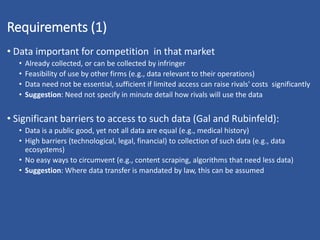

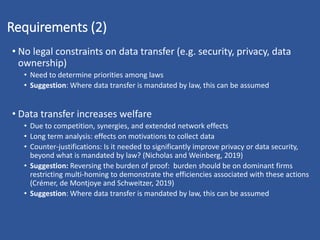

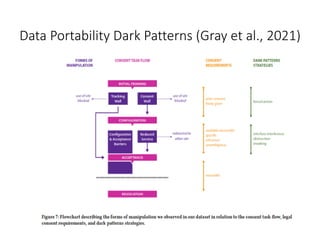

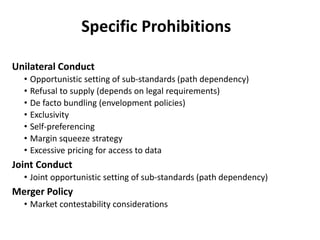

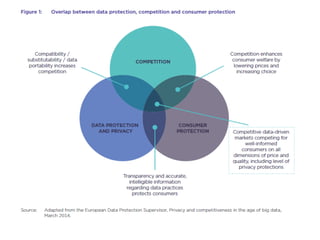

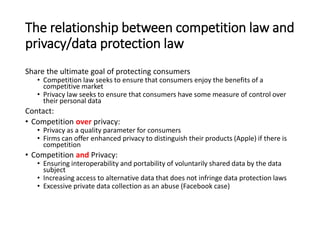

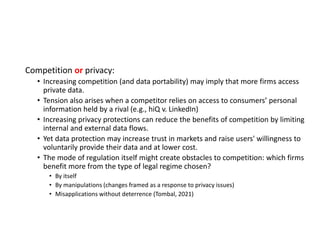

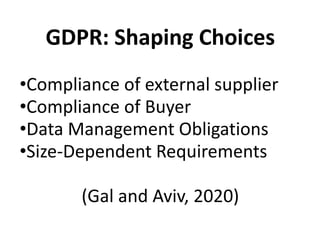

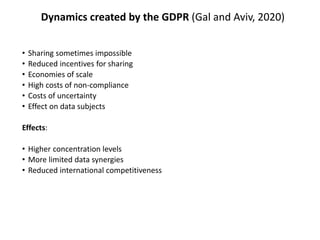

The document discusses how limitations on data interoperability and portability can constitute antitrust offenses by creating barriers to data access that negatively affect competition. It examines the implications of data collection practices, legal frameworks, and market dynamics in relation to consumer lock-in, switching costs, and competitive harm. The relationship between competition law and privacy law is also explored, highlighting the tension between promoting competition and ensuring consumer data protection.