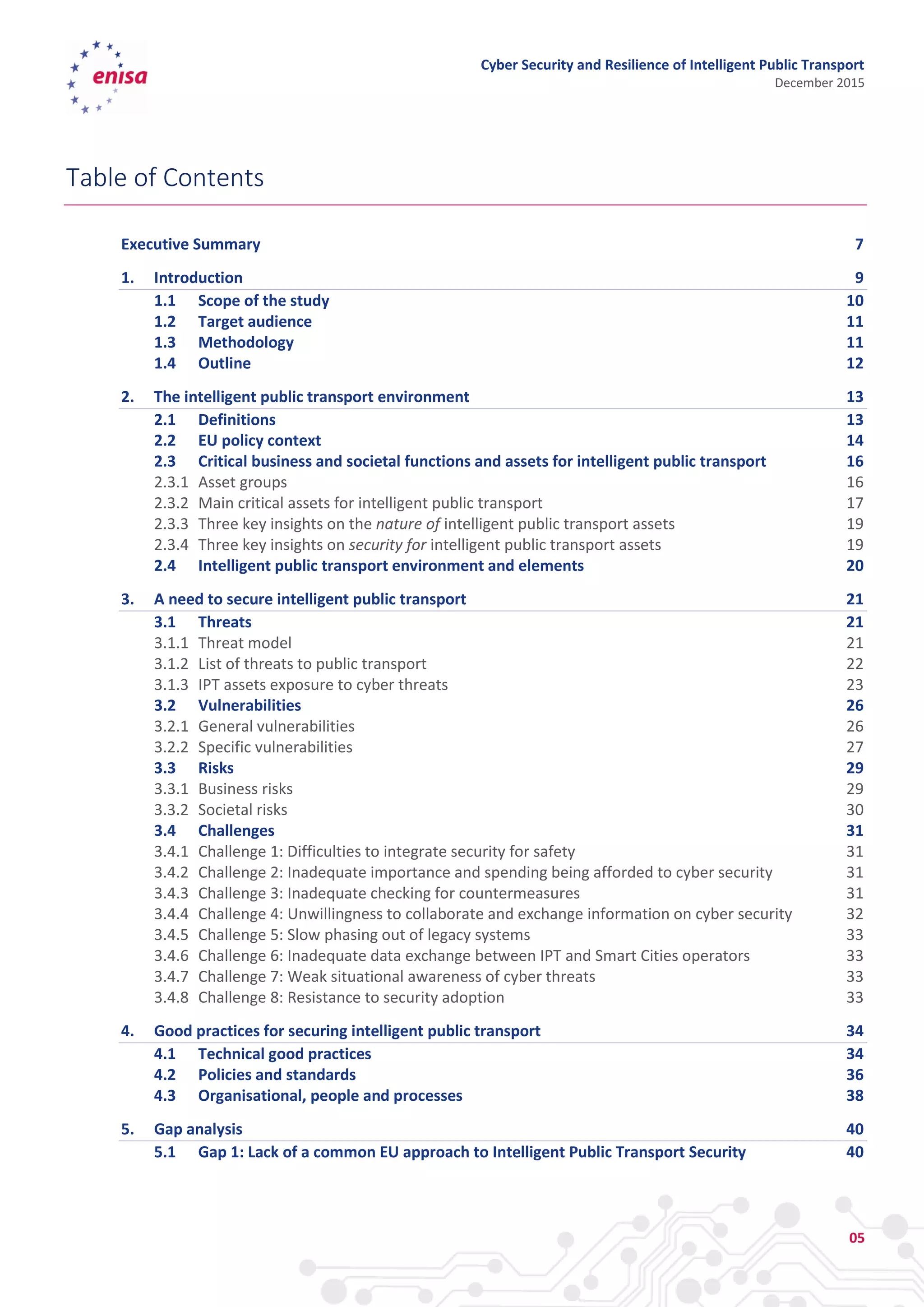

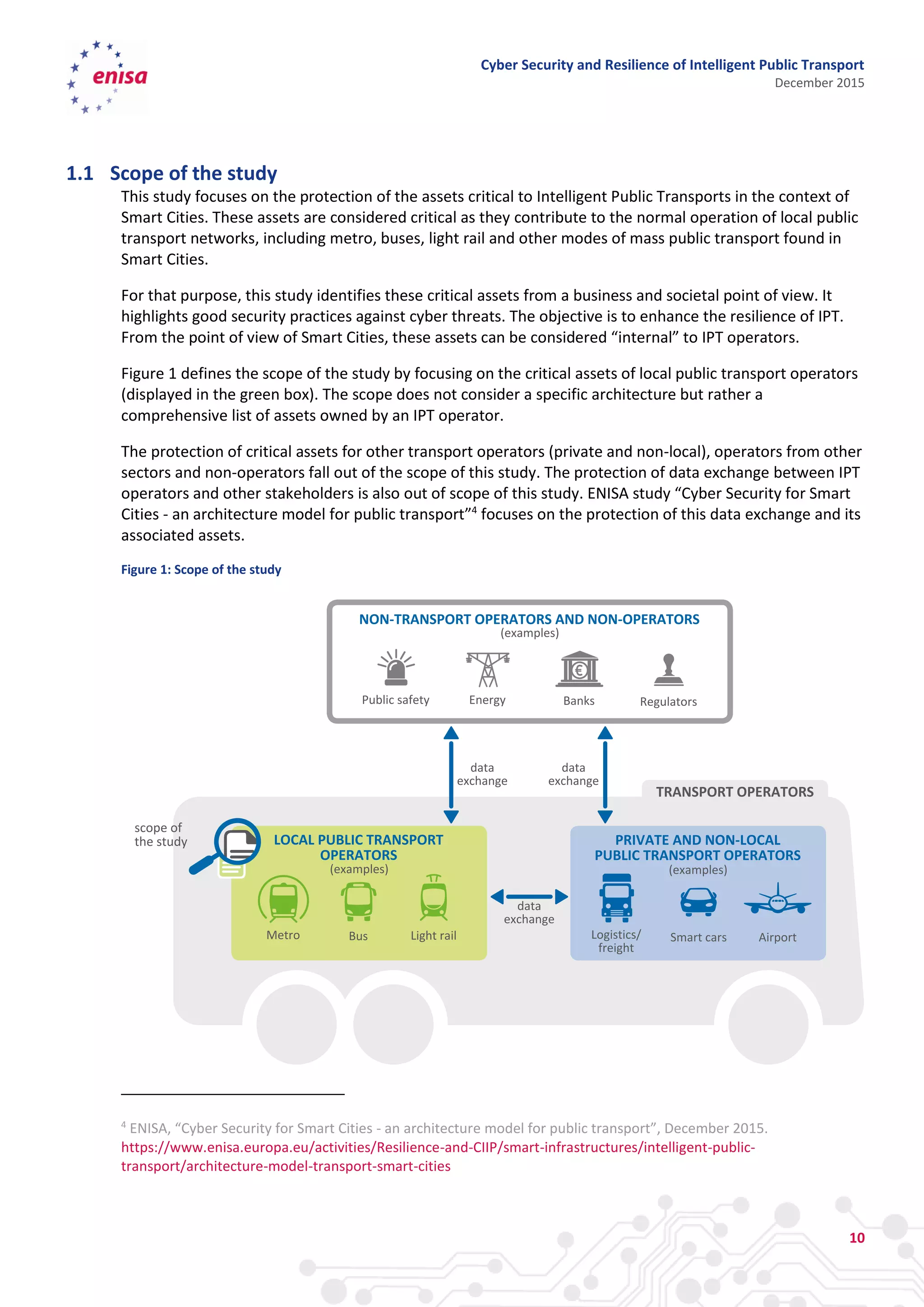

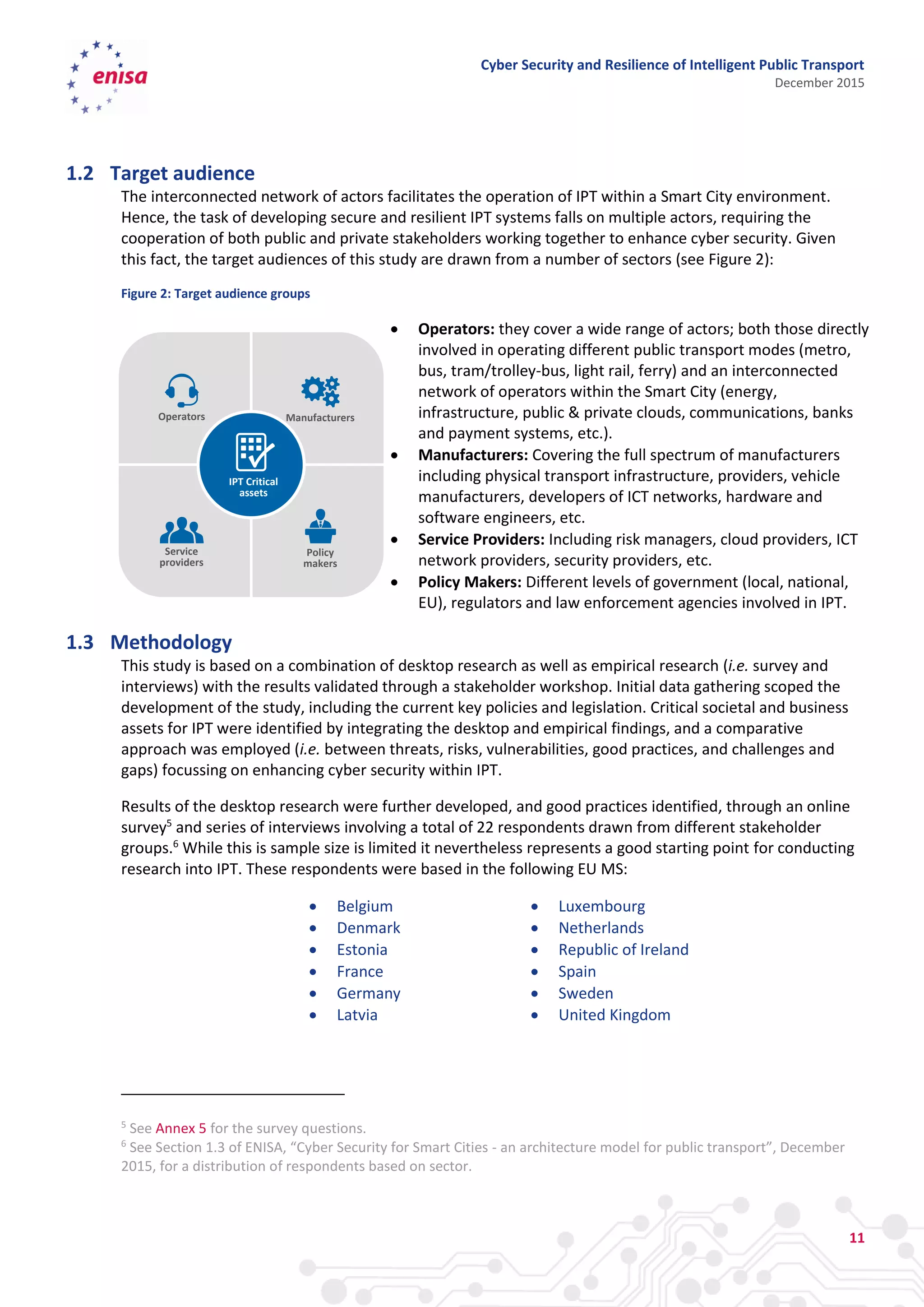

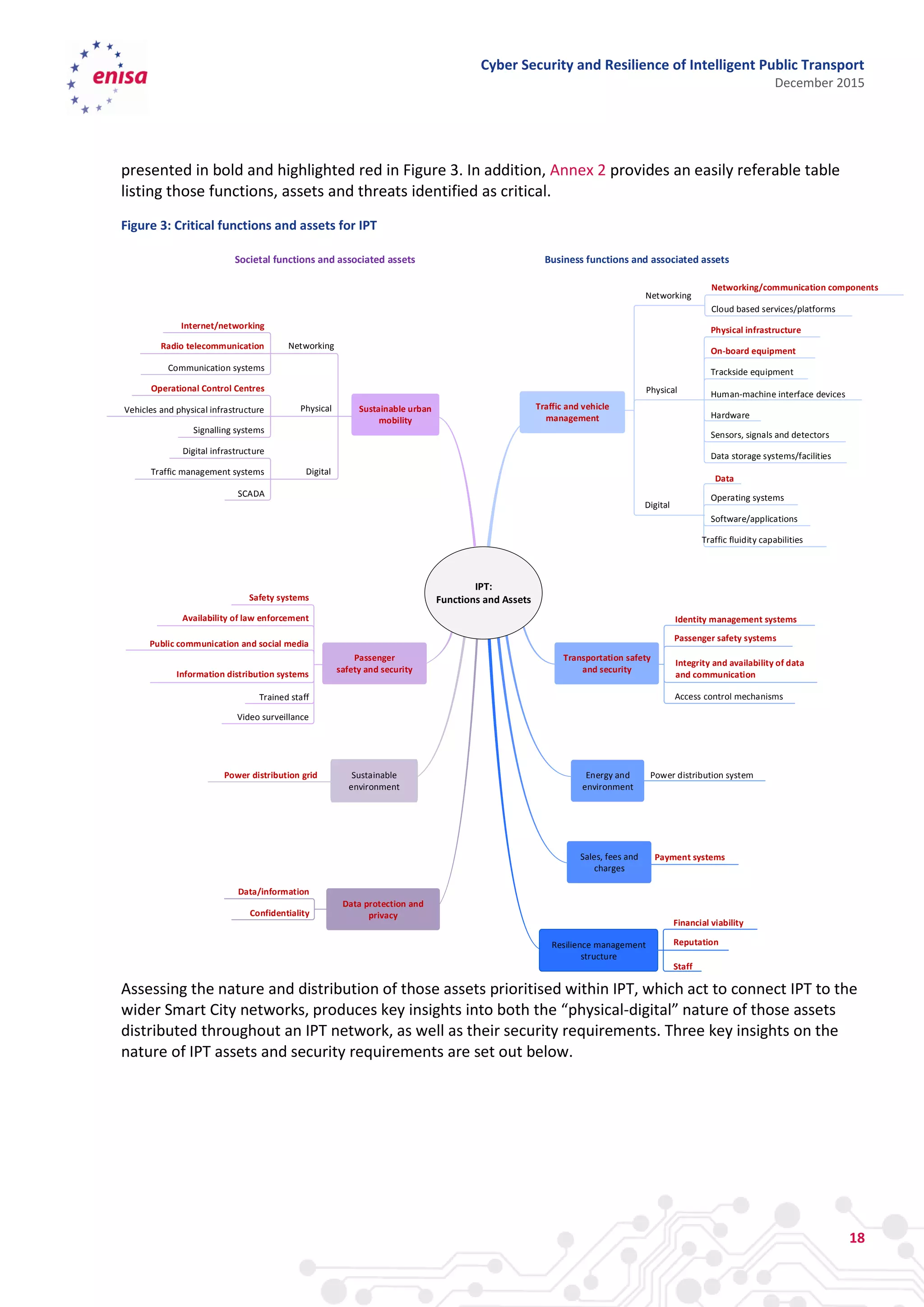

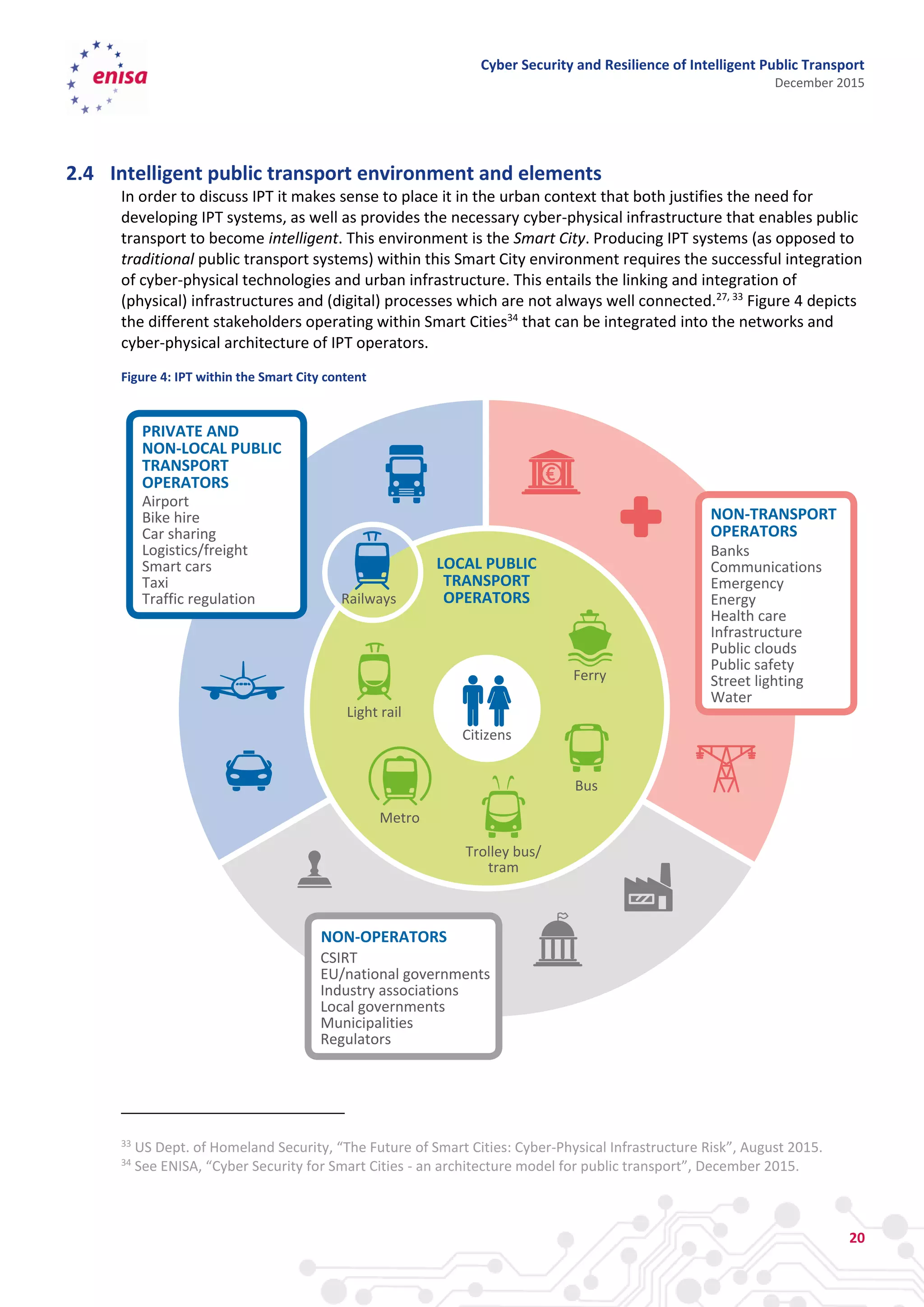

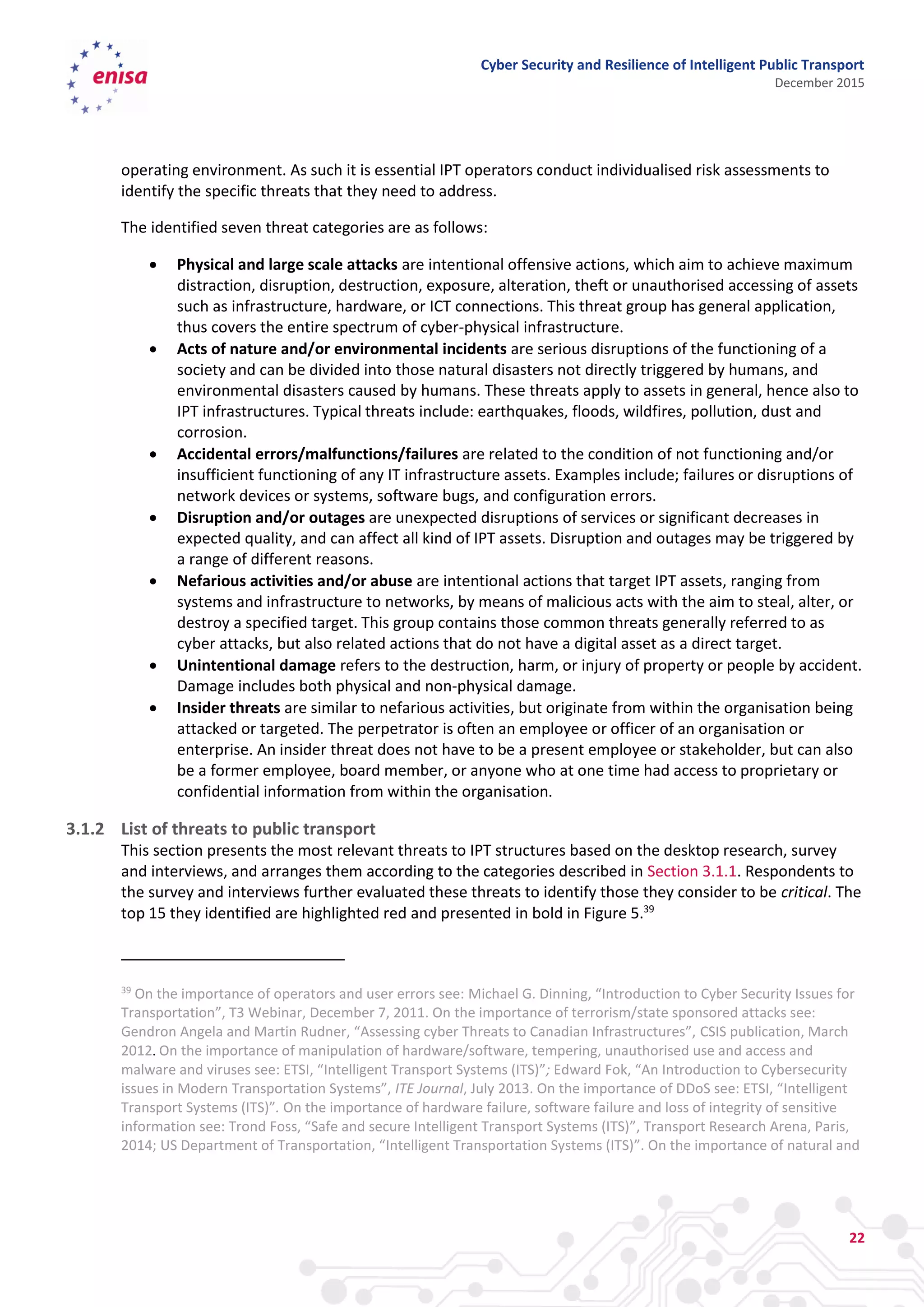

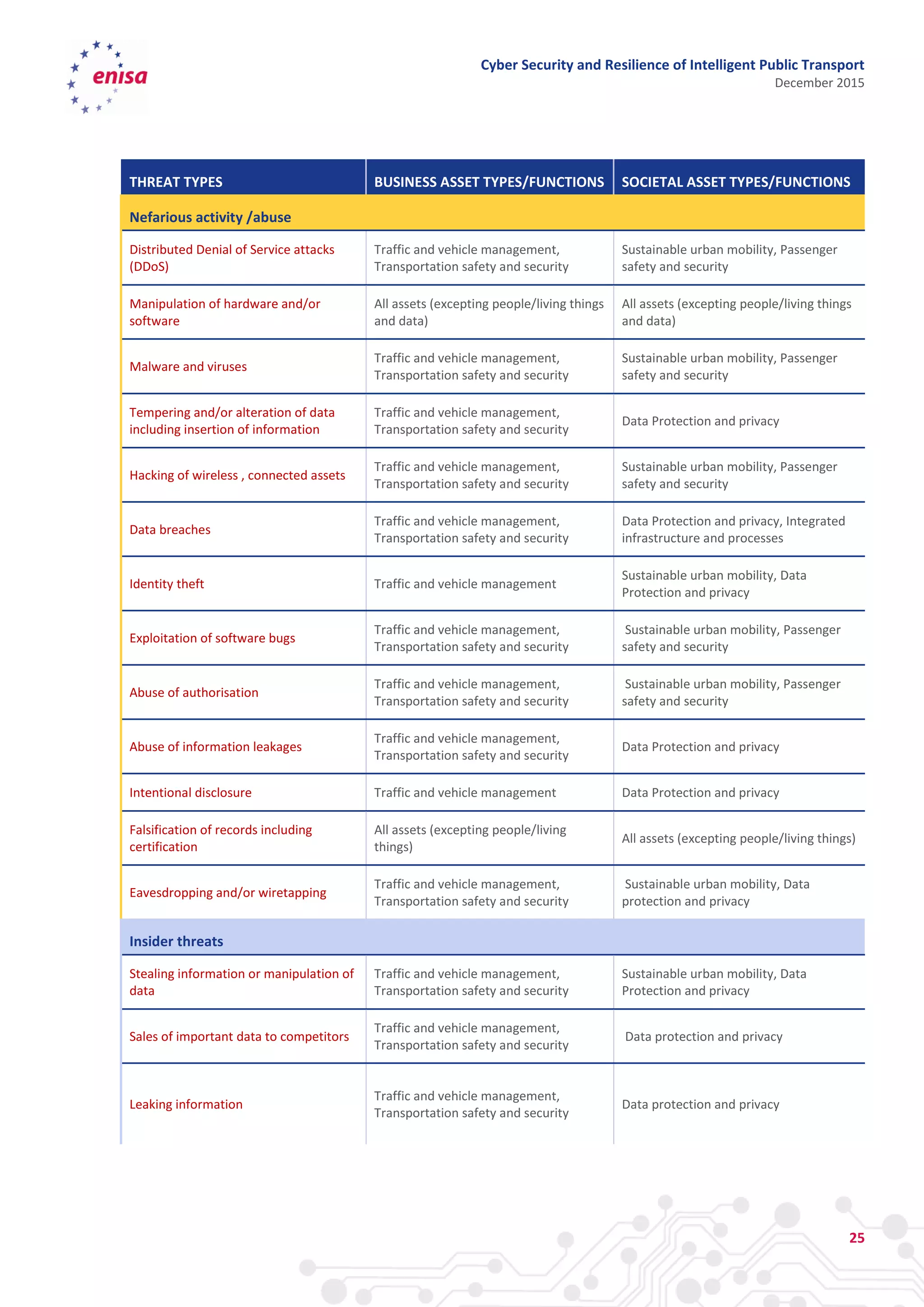

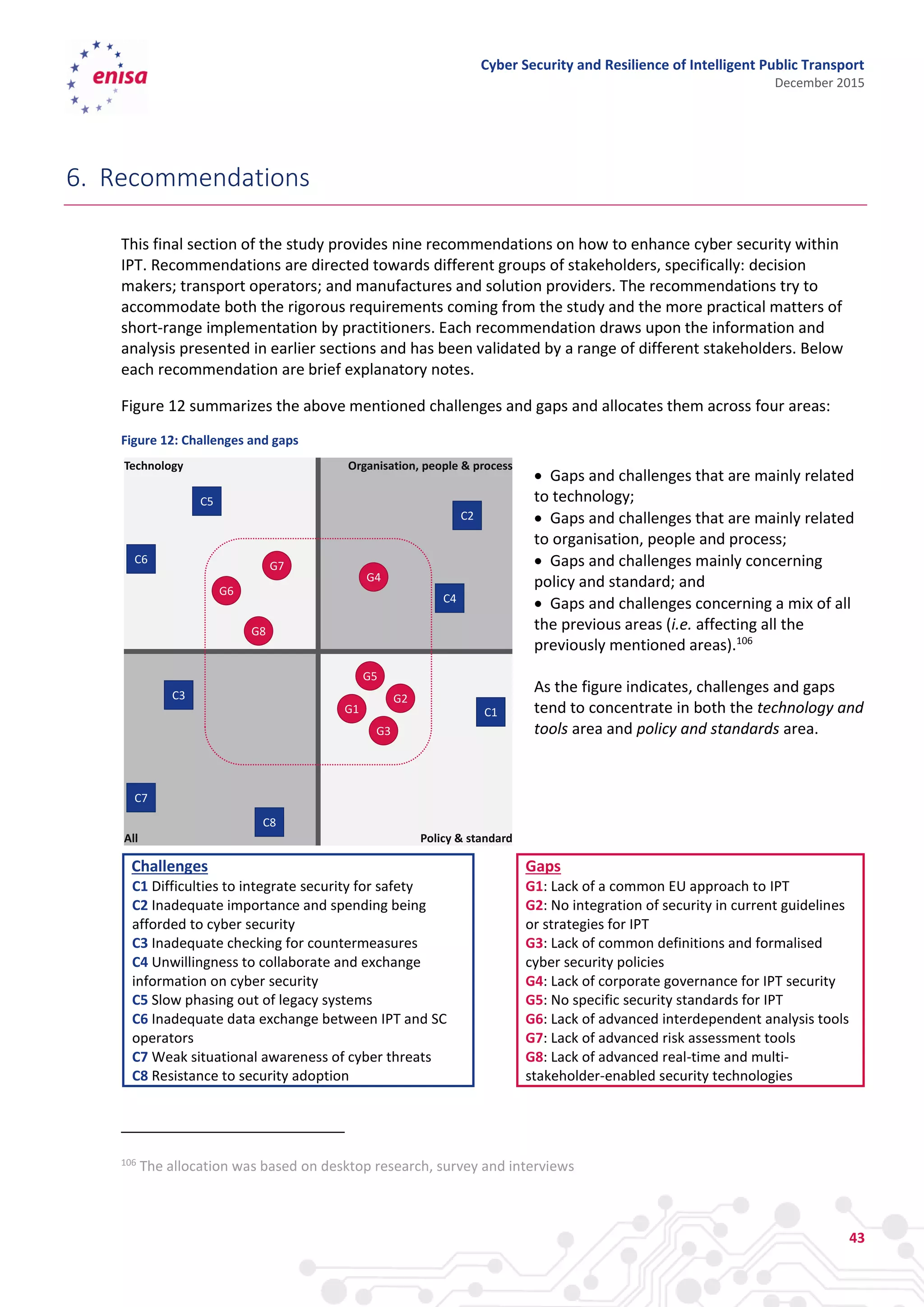

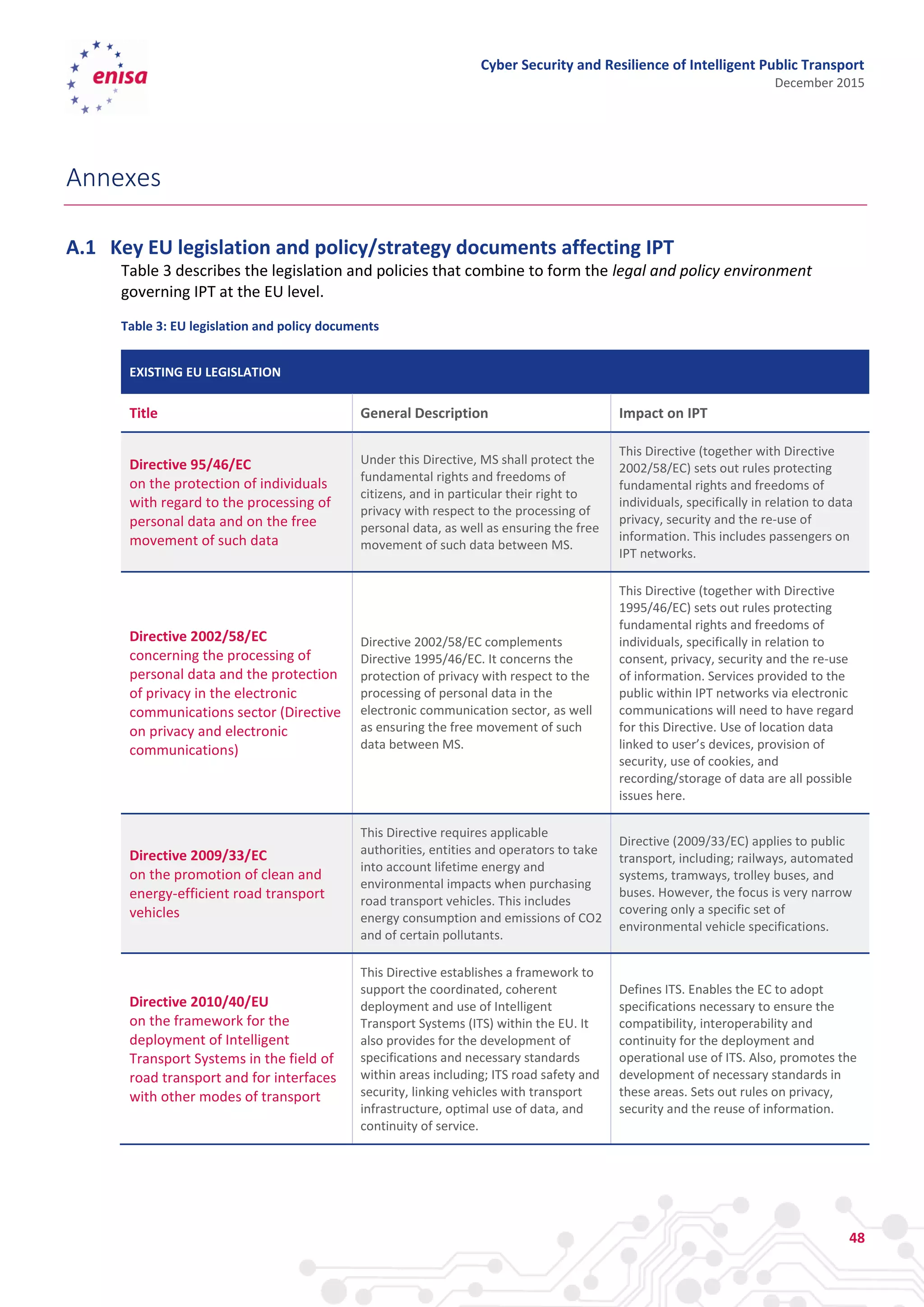

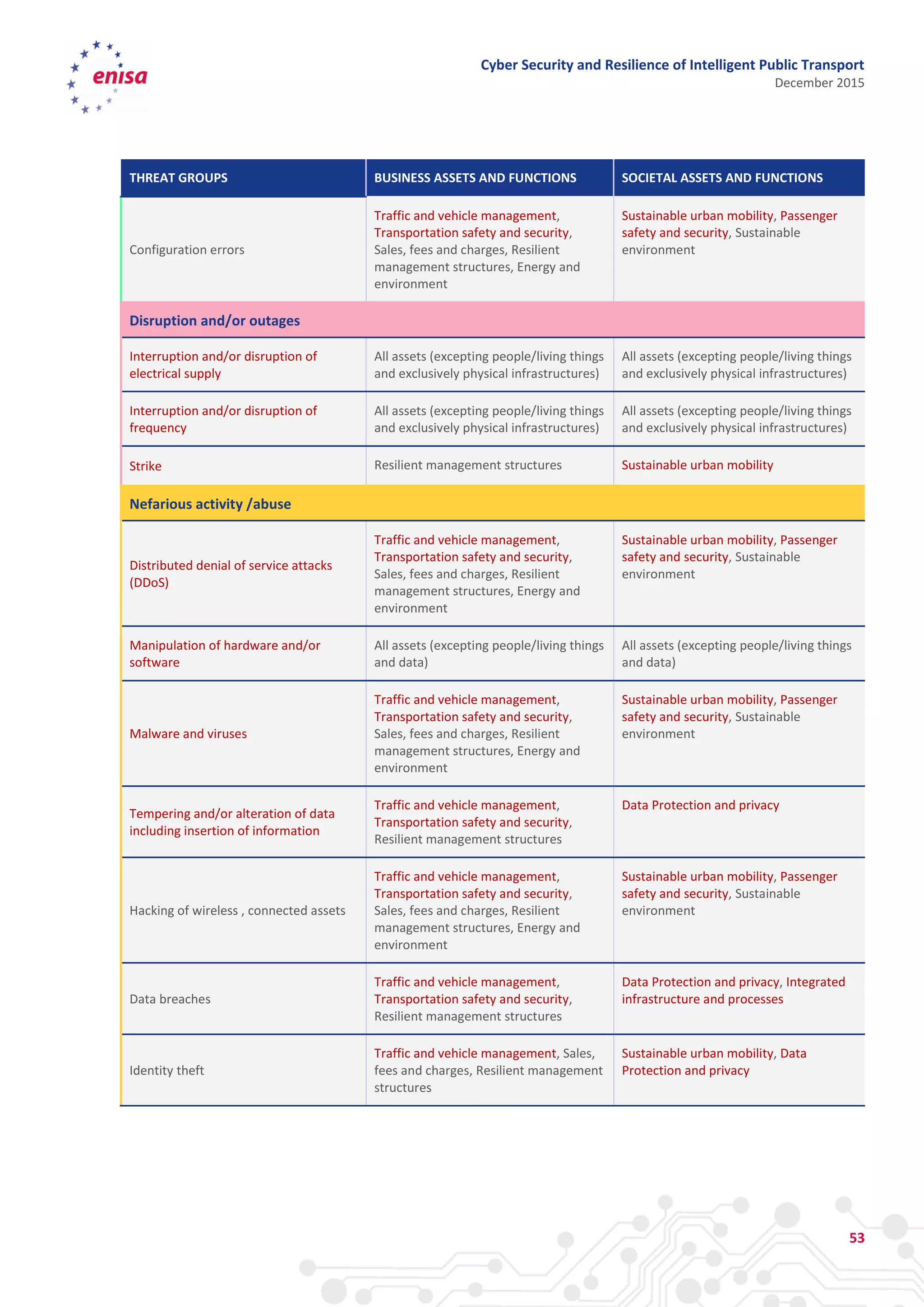

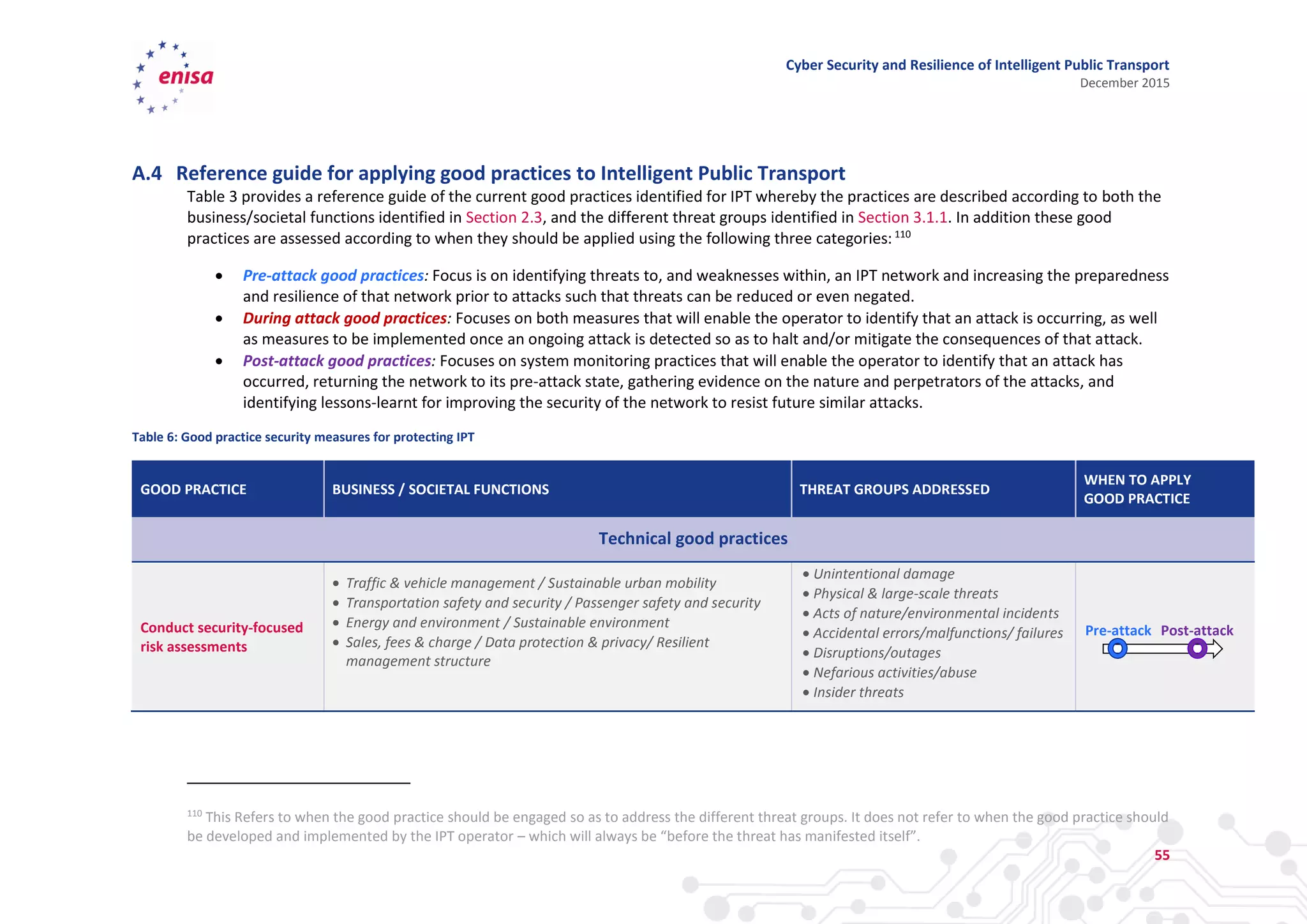

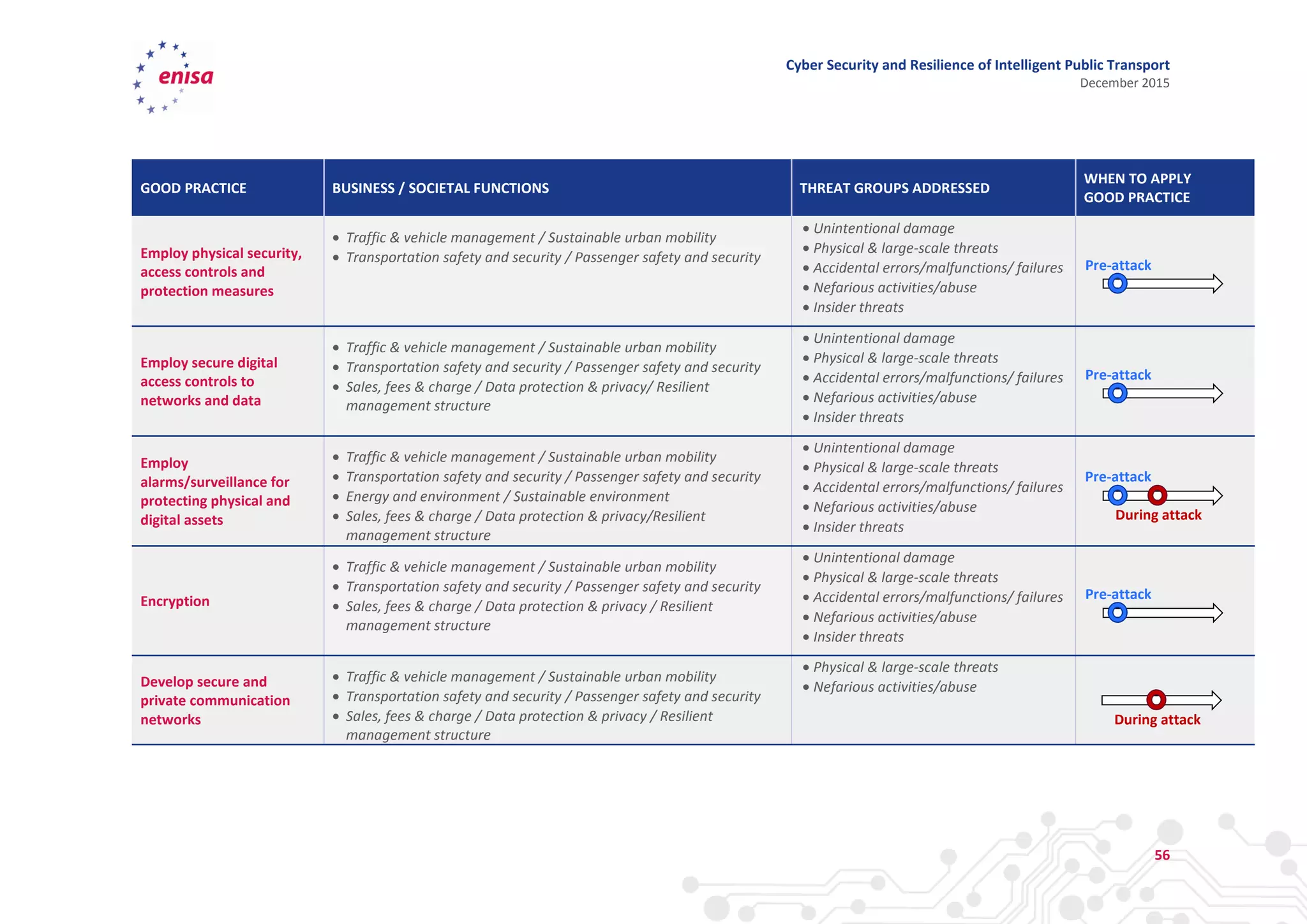

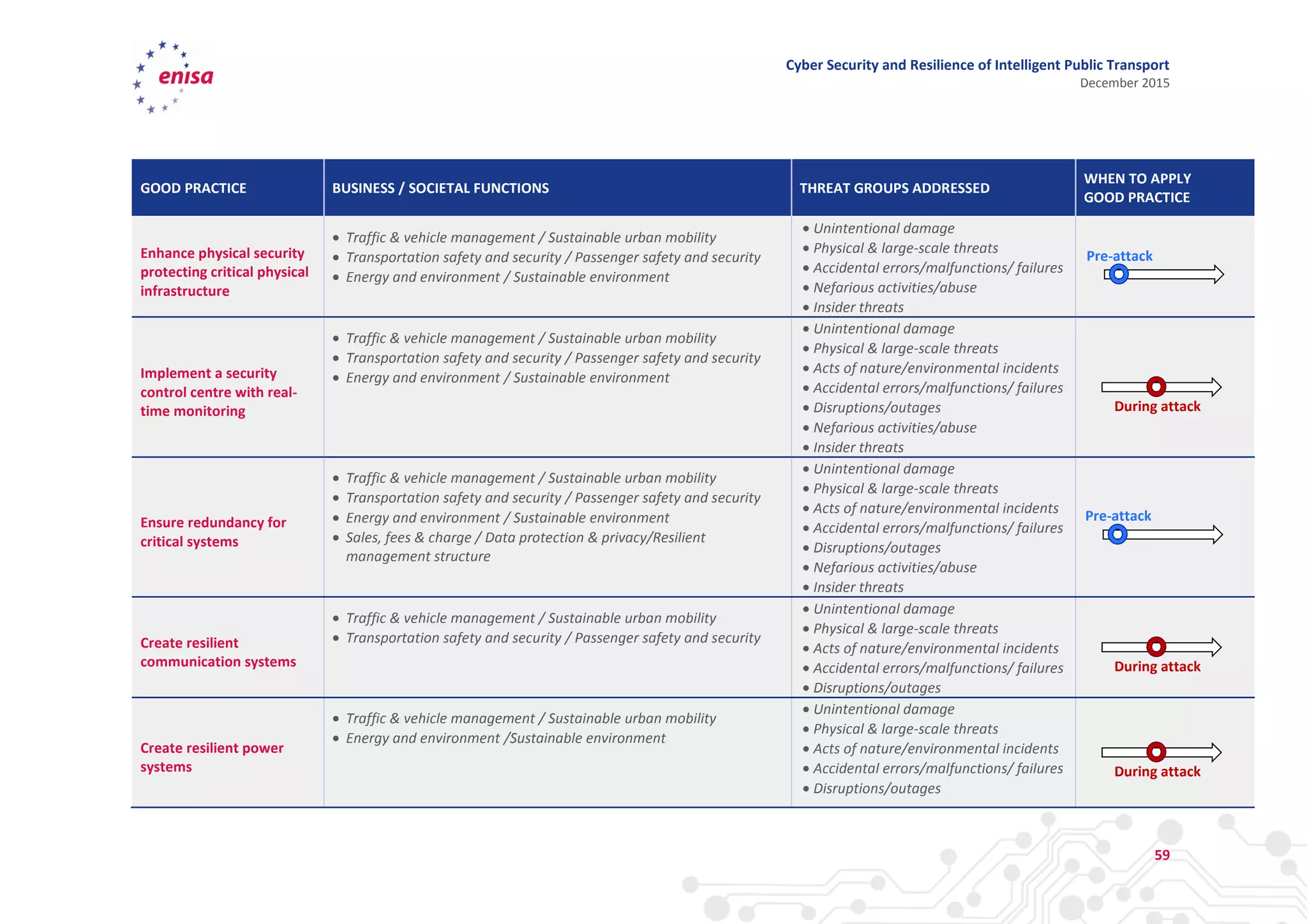

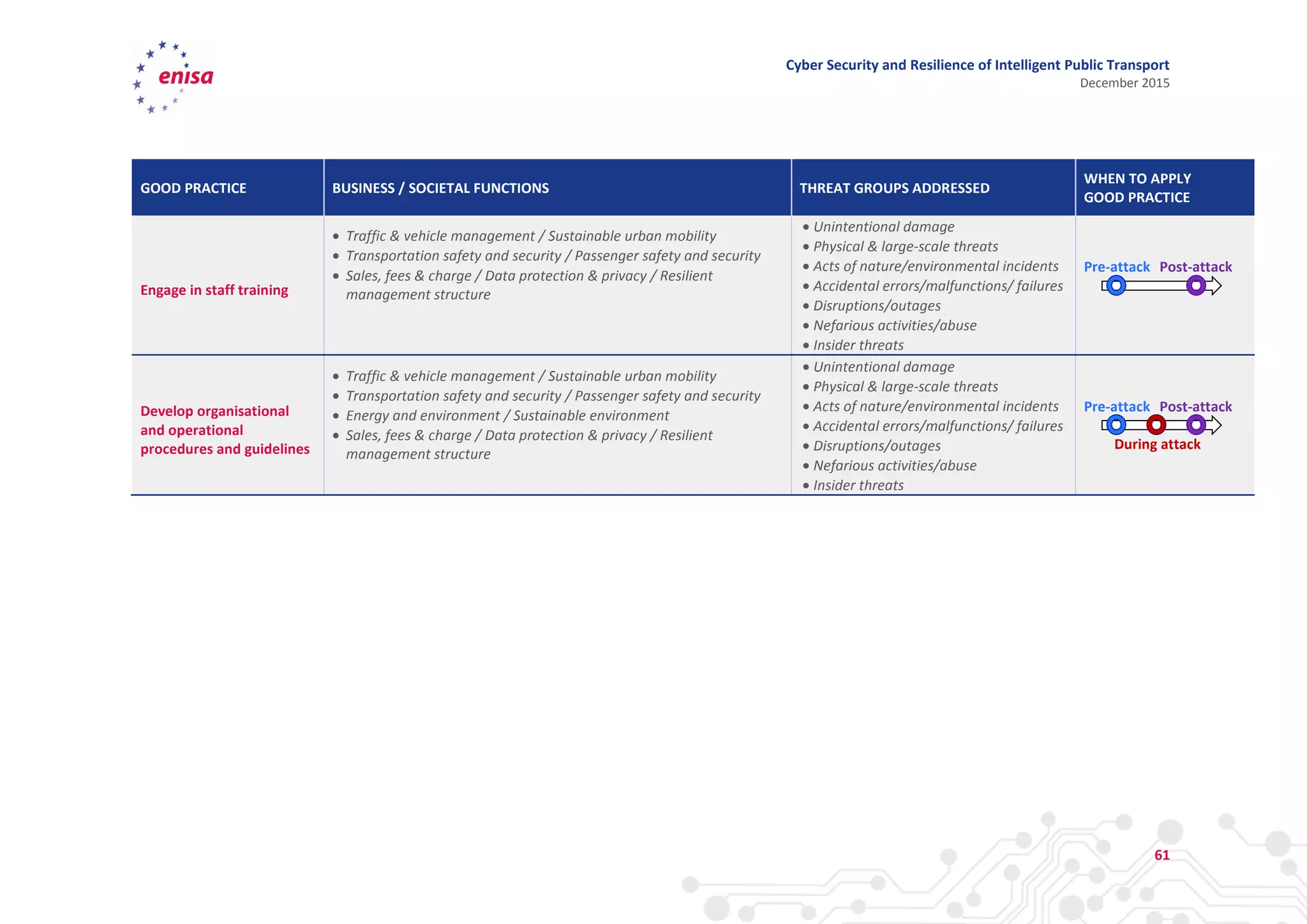

The document discusses cyber security and resilience in intelligent public transport systems. It provides an overview of intelligent public transport environments, the threats, vulnerabilities and risks they face from a cyber security perspective. It then outlines good practices for securing intelligent public transport, including technical, policy and organizational recommendations. Finally, it identifies gaps in cyber security for intelligent public transport and provides recommendations to decision makers, transport operators, and manufacturers/solution providers to help address these gaps.