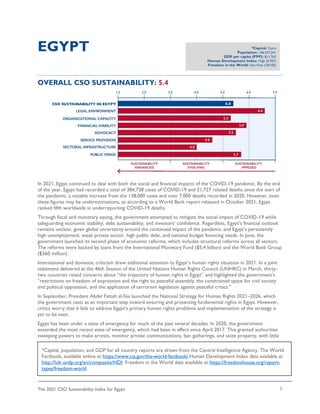

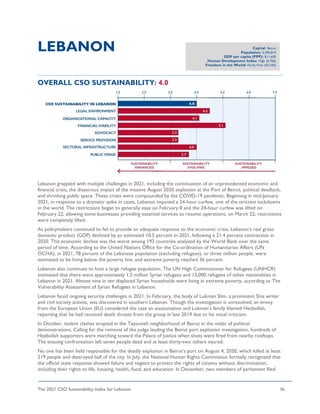

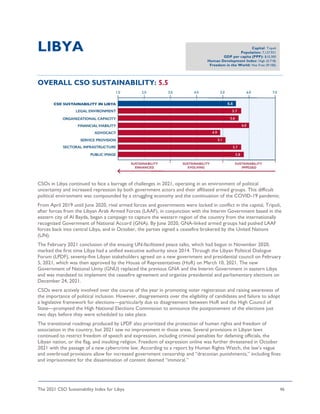

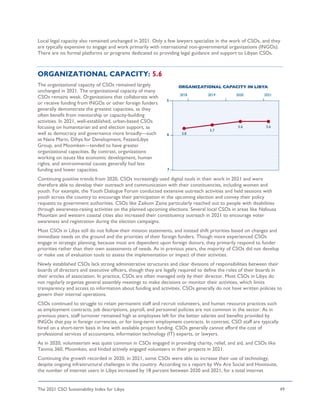

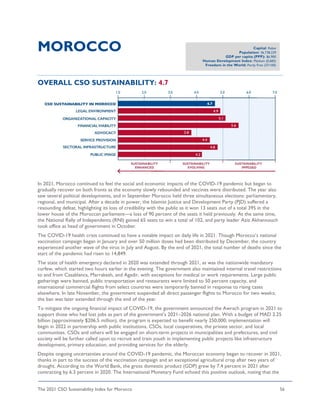

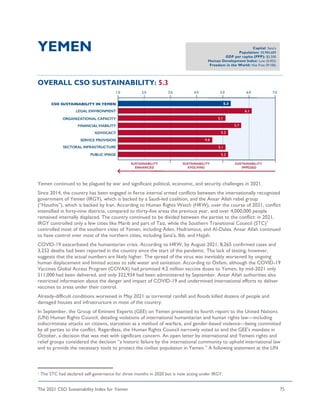

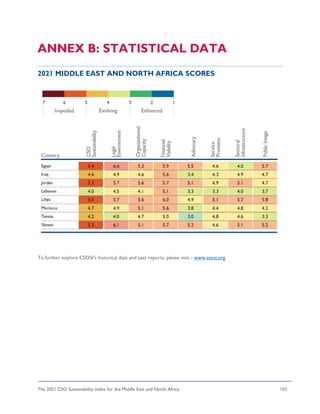

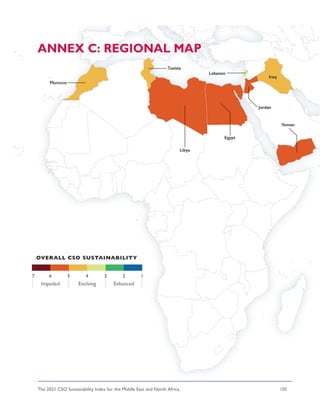

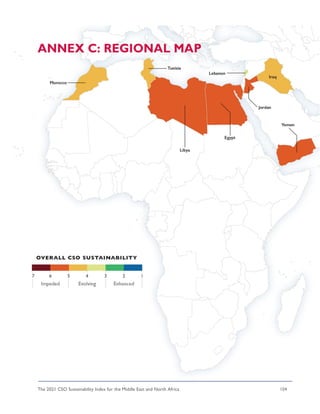

The 2021 Civil Society Organization (CSO) Sustainability Index for the Middle East and North Africa reports on the challenges and successes of civil society in eight countries, highlighting ongoing impacts from the COVID-19 pandemic, political unrest, and financial instability. It notes a general deterioration in the legal environment for CSOs in several countries, impacting their operations and advocacy efforts. Despite these challenges, many organizations adapted to continue meeting the needs of their communities.