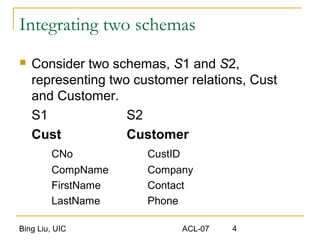

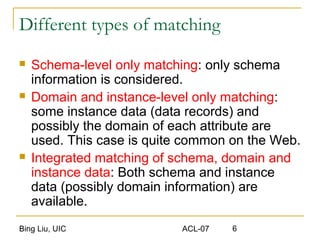

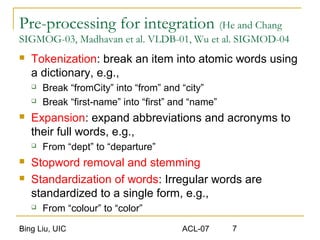

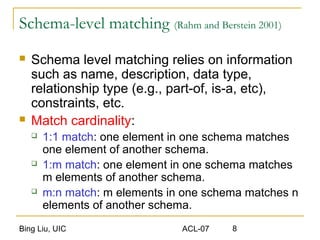

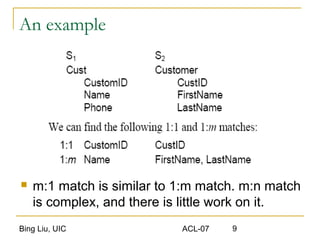

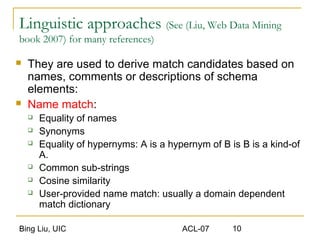

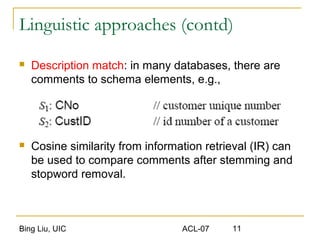

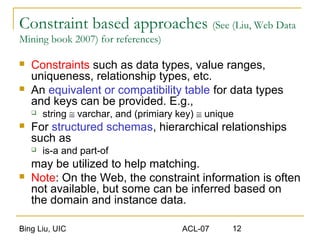

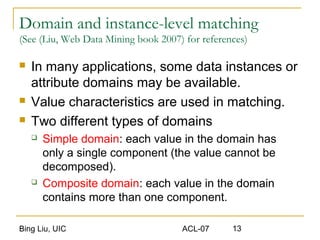

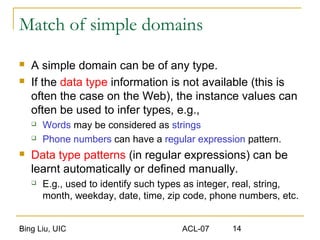

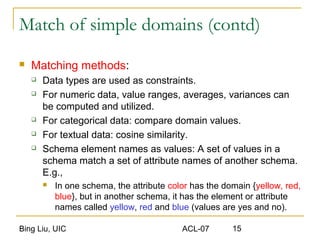

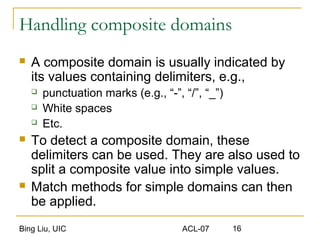

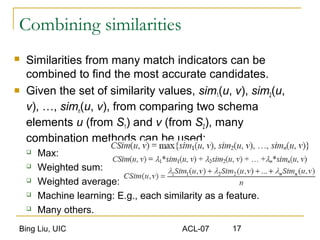

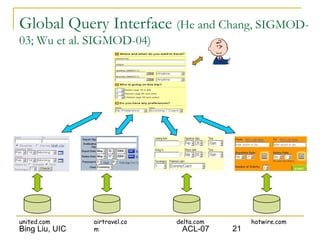

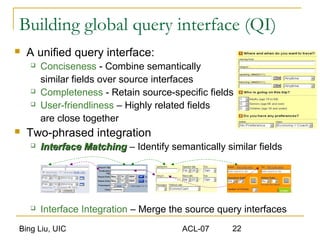

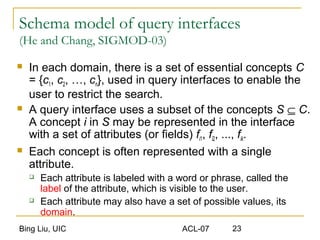

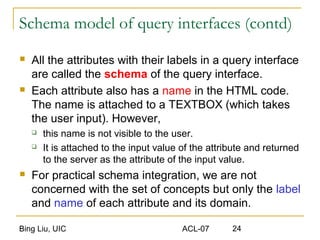

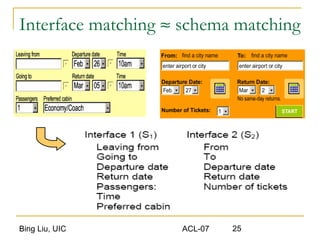

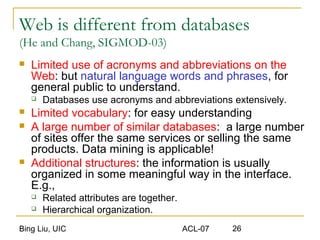

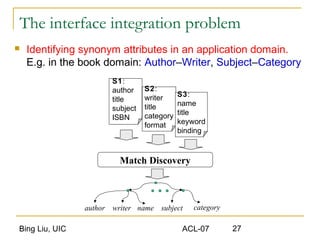

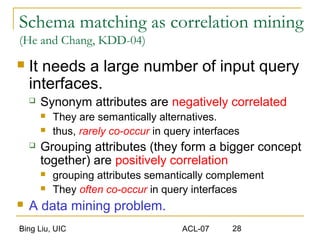

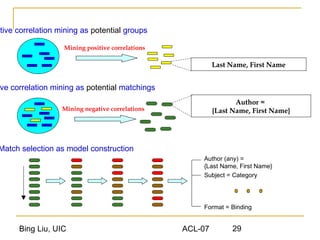

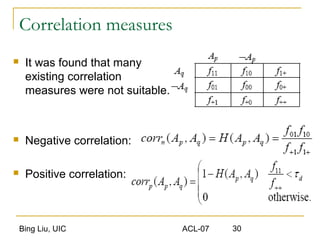

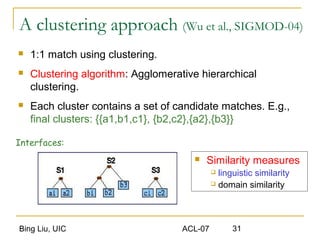

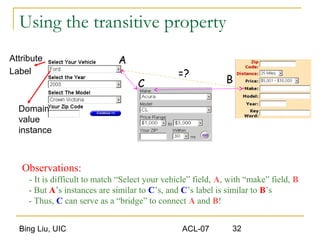

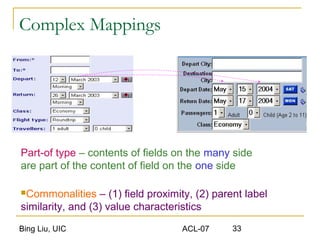

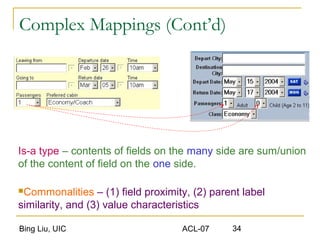

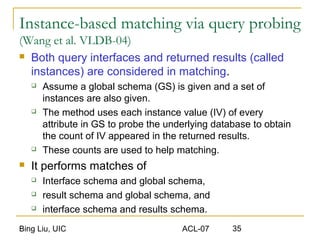

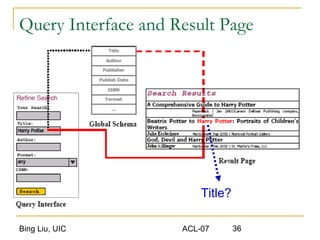

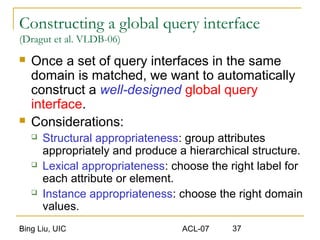

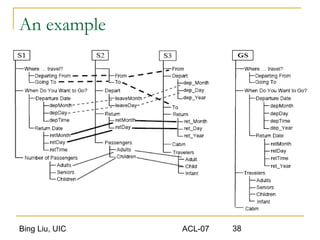

This document discusses techniques for integrating extracted data and schemas. It begins by introducing the problems of column and instance value matching during data integration. It then describes common database integration techniques like schema matching. It also discusses linguistic, constraint-based, domain-level, and instance-level matching approaches. Finally, it covers issues specific to integrating web query interfaces, such as building a global query interface and matching interfaces through correlation mining and clustering algorithms.