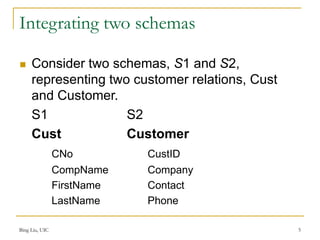

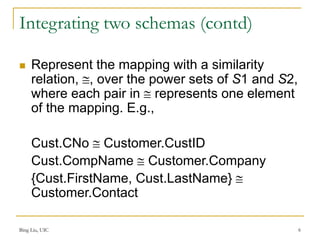

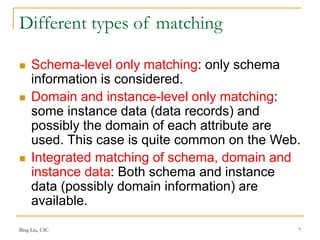

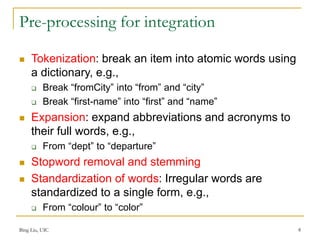

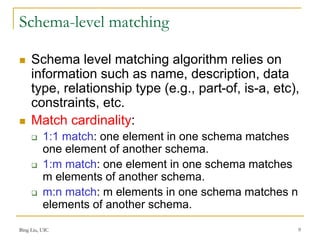

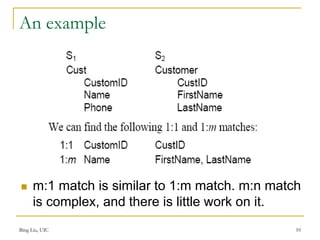

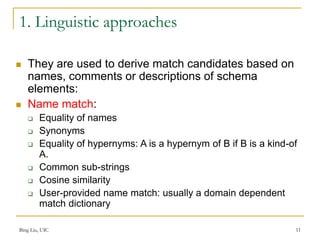

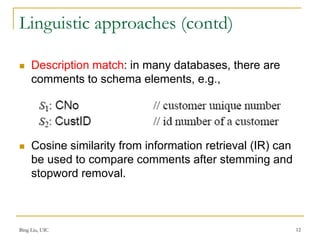

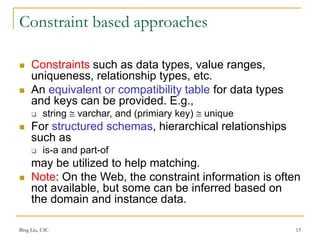

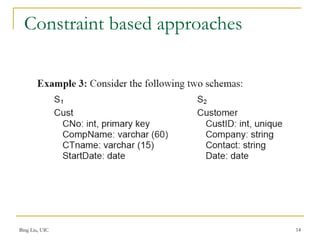

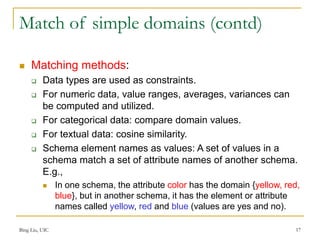

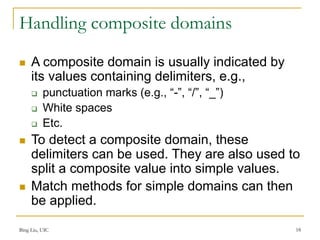

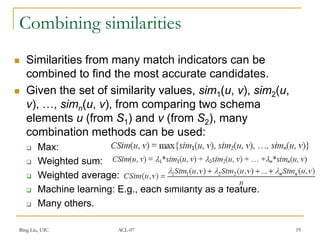

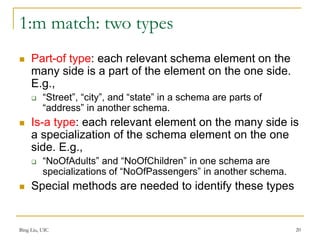

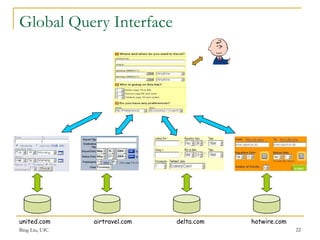

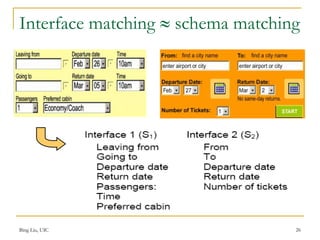

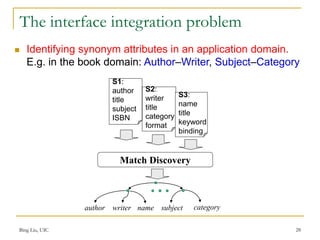

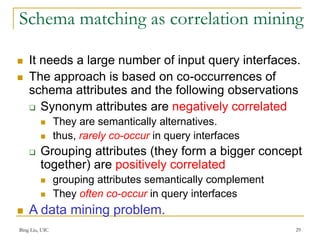

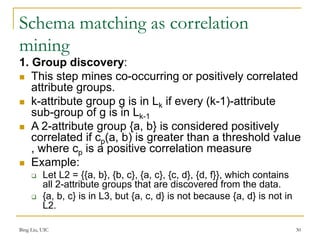

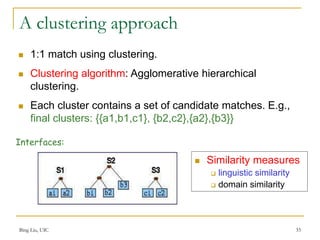

This document discusses techniques for integrating web query interfaces and schemas. It begins with an introduction to information integration and database integration, including schema matching. It then covers pre-processing techniques used for integration like tokenization and stemming. Schema-level matching techniques are discussed like name, description, and constraint-based approaches. Domain and instance-level matching uses value characteristics. Composite domains are handled by detecting delimiters. Similarities from different match indicators can be combined. Web query interface integration is introduced, with the problem being identifying synonym attributes. Schema matching is framed as correlation mining, covering group discovery, match discovery, and matching selection. A clustering approach to 1:1 matching is also presented.